GRAMMAR AND COMMUNICATION IN PORTUGUESE AS A

FOREIGN LANGUAGE

A Study in the Context of Teletandem Interactions

Douglas Altamiro Consolo, Aline de Souza Brocco

Department of Modern Languages, State University of Sao Paulo, Rua Cristovao Colombo

2265, Sao Jose do Rio Preto, Brazil

Camila Mendes Custodio

Department of Modern Languages, State University of Sao Paulo, Sao Jose do Rio Preto, Brazil

Keywords: Distant education, Foreign languages, Grammar, Portuguese, On-line interaction, Teletandem.

Abstract: This paper presents a study about the role of grammar in on-line interactions conducted in Portuguese and in

English, between Brazilian and English-speaking interactants, with the aim of teaching Portuguese as a

foreign language (PFL). The interactions occurred by means of chat and the MSN Messenger, and generated

audio and video data for language analysis. Grammar is dealt with from two perspectives, an inductive and a

deductive approach, so as to investigate the relevance of systematization of grammar rules in the process of

learning PFL in teletandem interactions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The growth of the economic and cultural

globalization has increased the need of foreign

language learning. Portuguese, the eighth most

spoken language in the world, stands as one of the

important foreign languages (FLS) to be learned

nowadays. The political and economic relations

between the countries of the Mercosul,

1

for example,

call for the spread and use of the Portuguese

language. Moreover, the increasing number of

foreign students in the Brazilian universities has

determined the implementation of courses of

Portuguese throughout the country.

The teaching of Portuguese as a foreign language

(henceforth PFL) has expanded in past fifteen years,

and it encompasses the development of course

materials and of a national examination of

proficiency in PFL, the CELPE-BRAS. However,

professionals in the area of PFL still find difficulties

concerning the “lack of human resources and

1

The alliance of four countries in South America: Argentina,

Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay.

material brought up to date and according to didactic

trends in language education” (Almeida Filho,

Oeiras and Rocha, 1998, p.2). According to

Kunzendorf (1987), this is because studies in PFL

have not been properly grounded in a specialized

theoretical framework. Therefore PFL constitutes an

important area for field work and research so as to

provide theoretical and empirical results for

education in Portuguese.

The main objective of this study is to investigate

the systematization of grammar in the process of

learning PFL in a teletandem context. The

participants are two undergraduate students of

Letters in Brazil, the proficient Portuguese speakers

who act as ‘teachers’, and two university students

learning PFL in the USA. Interactions were

conducted by means of the MSN Messenger, in

scope of a larger project called Teletandem Brazil:

foreign languages for all (www.teletandem.org).

This project aims at providing language training for

people who live geographically distant from each

other, in addition to significantly bring people from

different cultures to communicate. In this sense the

project creates the opportunity for Brazilian

university students to interact with partners from

several countries all over the world in order to (a)

62

Altamiro Consolo D., de Souza Brocco A. and Mendes Custodio C. (2009).

GRAMMAR AND COMMUNICATION IN PORTUGUESE AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE - A Study in the Context of Teletandem Interactions.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 62-66

DOI: 10.5220/0001973000620066

Copyright

c

SciTePress

develop their proficiency in foreign languages and

(b) teach PFL by means of online interactions. The

Teletandem Brazil project establishes a virtual

context for the teaching and learning of foreign

languages at a distance, aided by computers.

Teaching and learning happen concurrently in

listening, reading, oral production and writing, with

the aid of images and pictures.

The Brazilian interactants in the Teletandem

Brazil project are university students of Letters – a

BA course for teacher education in Portuguese and

in FLS, who participate as volunteers, that is, their

engagement in the project is not a formal

requirement of their university course. In the USA,

however, some of the interactants have to engage in

the project as a compulsory activity of their courses

of PFL.

According to Cziko and Park (2003), the

learning of languages in-tandem requires two native

speakers of different languages working in

collaboration with the intention to teach and learn

the languages involved. In this study the tutors of

PFL are being educators to become language

teachers and are also learners of English as a foreign

language.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

One of the principles for interactions in the

Teletandem Brazil project is the autonomy of

learners, since education is no longer under the

responsibility of the teacher. Learners then become

responsible for their own process of language

learning. In this way, the teletandem experience

allows for choices about goals, the content of

learning and the resources to be used, offering the

possibility of negotiation between the participants.

Another principle of teletandem is reflection, which,

according to Schön (1983) and Mezirow (1991),

bridges the traditional didactic asymmetry, in the

sense that the student also becomes a ‘teacher’ and

the teacher becomes as ‘student’. Moreover,

reflection offers the learners the possibility to

negotiate the course of the interactions and, as a

result, the route of their learning experience. A third

principle of teletandem interactions is reciprocity,

that is, both interactants are expected to act as

language ‘teachers’ and ‘learners’ so that they can

experience not only language development as

learners but also how to behave as the partner who is

more proficient in one of the languages involved. By

counting on language proficiency, on previous

experiences in foreign language learning - and on

teaching experience, if that is the case, and on

reflection, the most proficient interactant (the

‘teacher’) can decide on the actions in order to help

his or her partner learn a given foreign language.

In teletandem contexts the learner is expected to

have an active role in the teaching and learning

process, and s/he must therefore learn how to

become an autonomous learner in order to

accomplish the roles of teacher and student in such

contexts. Learners can count on the help from their

language teachers, and from another helper, a

participant of the Teletandem Brazil project who

acts a mediator. Mediation occurs in face-to-face

meetings and also by means of electronic contacts

between the mediator and each of the interactants.

Issues concerning language, cultural and interactive

aspects are dealt with in the mediation sessions.

In order to help learners to become proficient

language users and develop skills in listening,

speaking, reading and writing, they must be exposed

not only to opportunities to communicate in the

target language but also be exposed to the

grammatical rules that govern such language.

Otherwise learners run risk of producing non-

grammatical statements which may impair

communication. As learning in-tandem presents a

new way to learn languages, replacing or

complementing classroom approaches to language

teaching, this project aims at discussing how the

knowledge of grammatical rules by the students

helps in learning languages, as in the case of PFL.

On the other hand we must point out that the main

goal of interactions is communication, and grammar

is seen as one aspect of communicative competence

(Canale, 1983).

3 PROCEDURE

The interactions occurred by means of chat or audio

communication, with the help of the MSN, and

generated a corpus of written and spoken data. Oral

data were recorded by means of a software called

Easy Recorder, which is available on the Internet,

free of charge.

A teletandem session lasts two hours on average.

One hour is dedicated to each of the two languages

used by the interactants. In principle each session

comprises three parts: conversation, feedback on

language and evaluation of the session.

The first part consists of a conversation in the

target language, about one of more topics, and lasts

around thirty minutes. In the second part, which

GRAMMAR AND COMMUNICATION IN PORTUGUESE AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE - A Study in the Context of

Teletandem Interactions

63

takes approximately twenty minutes, the interactants

discuss the language used in their previous

conversation and the more proficient interactant has

the opportunity to provide linguistic feedback to his

or her partner, with the help of notes written during

the conversation or, in the case of written

communication (chat), by referring to the previous

lines of their interaction. The third part of the

session usually lasts ten minutes and is dedicated to

evaluating the whole session, focusing on the

difficulties faced by the participant while interacting

in teletandem and on suggestions for future action.

It has been observed in the data from the

Teletandem Brazil project as a whole that most of

the interactants initiate the contacts with their

partners by e-mail, and then interact by means of

chat, and only after a period of familiarization with

each other they start using audio and video resources

to communicate. Salomão (2006) analyzed diaries

produced by interactants, which indicate that some

participants felt somehow afraid or ashamed to start

interacting by means of audio and video, due to

either their lack of proficiency in the target language

or little experience in using computer resources for

communication. Benedetti (2006) states that there

may be differences in the technical conditions

available for the interactants. While interactants in

Brazil can make use of their own home computers or

use the equipment available in well-equipped

laboratories at university, not all the interactants in

the other countries had easy access to computers

with microphones and video cameras.

In this investigation, an inductive and a

deductive approach are used to study the

systematization of grammar in teaching-learning of

PLE in the context of teletandem interactions. Based

on the deductive approach, first the student's

inadequacies regarding the structures of Portuguese

are checked, especially if statement undermine

communication between the interactants, and those

‘gaps’ in the learner’s knowledge of grammatical

rules are addressed by the teacher in future

interactions. Thus the teaching occurs from the

difficulties and needs of students. For example, if

during the interaction it is noticed that the learner

does not have proper control over the use of

imperfect past – a verb tense which has different

uses and one of them is in combination with the Past

Perfect, the teacher deals with the differences

between the uses of the verb tenses in Portuguese.

By means of the inductive approach the teacher

motivates the interactant (=the ‘student’)to produce

sentences using a given grammar topic to be

addressed during the interaction, that is, if the choice

is verb tenses to express past ideas, the learner is

asked to speak, for example, about past experiences.

Such procedure helps the use of selected structures

for authentic communication, and highlights the

grammar topic to be addressed.

It is worth mentioning that since we deal with

learners of PFL who speak English as their first

language, there are differences - syntactic, semantic,

phonetic and morphological - between the learner's

mother tongue and Portuguese, a language of Latin

origin.

The corpus of interactions was analyzed so as to

raise and discuss the occurrences of difficulties the

interactants in the USA had when producing the

Portuguese language, namely the occasions in which

lack of grammar competence disturbed or impeded

clear communication.

4 RESULTS

In the following extract (Extract 1) we can observe

how one of the the Brazilian interactants helps the

North-American person deal with the perfect past in

Portuguese ( I-USA1 = the North-American

person; I-BR = the Brazilian person ):

2

Extract 1

I-USA1: no passado, como conjugas os verbos

In the past, how do you conjugate the verbs?

I-BR: Você já aprendeu algum tipo de passado?

Have you already learned any type of past

tense?

I-USA1: nao, nada

No, not yet

I-BR: Então, vou te explicar como funciona o

Pretérito Perfeito, que seria semelhante ao Past Simple,

certo?

Then I’ll explain to you how the simple past in

Portuguese is produced, which is similar to the simple

past in English, all right?

I-USA1: sim

Yes

I-BR: Para cada pessoa eu tenho uma forma do verbo,

como no espanhol. Eu amei. Tu amaste. Ele amou. Nós

amamos. Vós amastes. Eles amaram. Esta é a conjugação

do verbo "amar" no pretérito perfeito.

For each person we have a verb form, as in

Spanish. I loved. You loved. He loved. We loved. You

loved. They loved. This is the conjugation of the verb

“love” in the simple past.

I-USA1: ah, mas você no usa tu e vós, verdade?

Ah, but you don’t use “tu” and “vos”, right?

2

From Brocco, 2007. The English version of the statements is in

italics.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

64

I-BR: Todos os verbos regulares terminados em -ar

vão formar o pretérito perfeito desta forma. Como o

cantar, dançar, lavar, digitar, etc.

All the verbs that end in –ar Will form the

simple past in this way. Like sing, dance, wash, type, etc

I-USA1: Sim, nós não usamos o "tu" e o "vós"

Right, we don’t use “tu” and “vos”.

I-USA1: SIM, COMO FALEI, LAVOU, ETC.

Yes, like I said, washed, etc.

I-BR: Isso mesmo.

That’s right.

I-USA1: QUANDO FUI A PORTUGAL VI MUITO

DE TU E VÓS.

When I went to Portugal I saw a loto f “tu” and

“vos”.

I-BR: Você usou o pretérito de forma correta.

You used the simple past correctly.

I-BR: Lá em Portugal eles usam muito "tu" e "vós",

mas aqui no Brasil nós não usamos.

In Portugal they use “tu” and “vos” a lot but

here in Brazil we don’t (use these two forms).

I-USA1: muito bem, e os verbos -er, como são?

All right, and the verbs in –er, how do they

work?

I-BR: Eu vendi. Tu vendeste. Ele vendeu. Nós

vendemos. Vós vendestes. Eles venderam. Isso só para os

regulares terminados em -er. Há muitos verbos terminados

em -er que são irregulares. Por exemplo, ver, dizer, ser,

ter, etc.

I sold, You sold. He sold. We sold. You sold.

They sold. This is only for the regular verbs ending in – er.

There are verbs ending in –er which are irregular. For

example, see, say, be, have, etc.

I-USA1: SIM, E -IR SÃO: PARTI, PARTIU,

PARTIMOS, PARTIRAM?

Yes, and (for) –ir (we have) departed, departed,

departed, departed?

I-BR: Eu parti. Tu partiste. Ele partiu. Nós partimos.

Vós partistes. Eles partiram.

I departed. You departed. He departed. We

departed. You departed. They departed.

The North-American interactant (I-USA1) is able to

infer the perfect past form for the verbs ‘falar’ (say)

and ‘lavar’ (wash), and for the verbs ending in ‘-ir’,

like ‘ir’ (departed), which is an irregular verb. All

the inferences made by I-USA1 were successful.

In Extract 2 we have an example of a problem

USA1 has to use the correct gender of the article

before the word “rio” (river), which is masculine in

Portuguese, then it should be “do rio”:

Extract 2 (from Brocco, 2007)

I-USA1: você sabe o que é St. Patrick's Day?

Do you know what St. Patrick’s Day is?

I-BR: sim

Yes.

I-BR: o que acontece neste dia?

What happens on that day?

I-USA1: tudo está

3

verde, as roupas, as ruas e também

é normal que a gente bebe muito.

Everything is Green, the clothes, the streets

and it is normal to drink a lot.

I-USA1: veja esta foto DA RIO

em Chicago

Have a look at this picture of the river in

Chicago.

http://chicagomamaspot.typepad.com/photos/uncatego

rized/chicago_river_green

[...]

In Extracts 3 and 4 (from Custódio, 2007) we see

examples of the difficulty to use the verbs “estar”

and “ser”:

Extract 3

I-USA2: estão aqui 9:30

It is 9:30 here

Extract 4

I-USA2: agora no Brasil esta verão

It is summer in Brazil now

A summary of the main difficulties faced by the

other North-American interactant, I-USA2, which

are similar to the problems presented in the

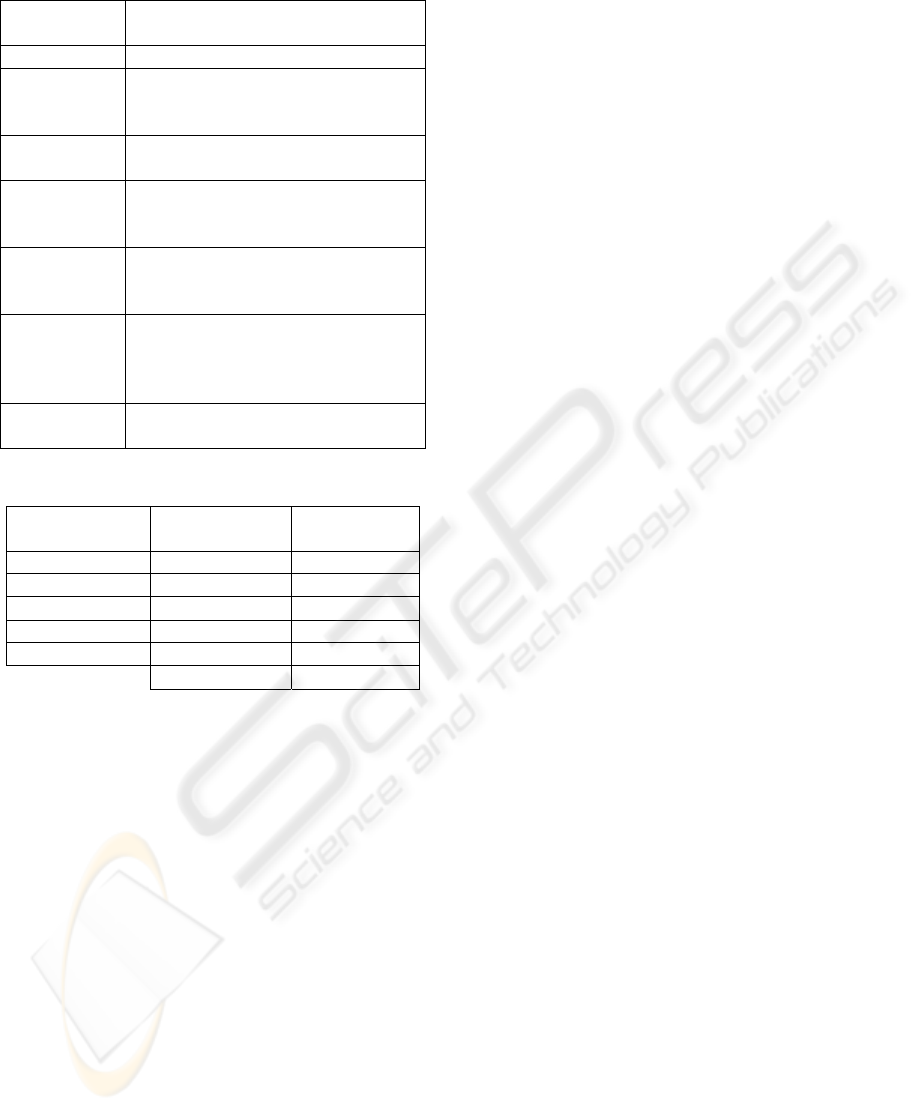

interactions with I-USA1, is presented in Table 1:

To finish the data analysis we show the types

and frequency of linguistic feedback provided to I-

USA1 by the Brazilian interactant. We consider as

feedback all types of reflection about linguistic

items, including grammar, vocabulary, spelling,

discourse and phonology.

Table 2 presents the frequency of the three types

of feedback found in the data:

3

Instead of “tude está verde” USA1 could have used “tudo é

verde”. This example indicates his difficulty to use the verbs

“estar” and “ser”, which correspond to “be” in English.

GRAMMAR AND COMMUNICATION IN PORTUGUESE AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE - A Study in the Context of

Teletandem Interactions

65

Table 1: Difficulties in grammar in PFL.

GRAMMAR

TOPIC

DIFFICULTY FACED BY I-USA2

word gender I-USA2 does not use articles correctly.

verbs ‘ser’

and ‘estar’ in

Portuguese

Since both verbs correspond to ‘be’ in

English, I-USA2 cannot make clear distinctions

in meaning.

Prepositions I-USA2 had some difficulty to use some

prepositions in Portuguese..

subject &

verb agreement

I-USA2 had problems to use some verb

forms because in Portuguese verb forms vary

according to the subject pronouns.

Pronouns I-USA2 has problems concerning both

subject-pronoun agreement and to use pronouns

after subjects.

affirmative

& negative

structures

In English it is possible to use “I don’t

think” + an affirmative sentence; in Portuguese

you must say “Eu penso” (I think) + a negative

sentence.

past tenses I-USA2 had problems with the use of

several past tenses.

Table 2: Types of linguistic feedback.

Types of

linguistic items

Number of

occurrences

Percentages

Grammar 44 28,4%

Vocabulary 78 50,3%

Spelling 8 5,2%

Discourse 21 13,5%

Phonology 4 2, 6%

Total: 155 Total: 100%

The information in Table 2 reveals that most of the

linguistic feedback (50,3%) focused on vocabulary,

a rather expected fact. Foreign language learners

usually need help to learn new words and when they

face lack of words while the language learning

process develops.

The amount of feedback on grammar, the focus

of this investigation, was not very high. However,

the frequency observed (28,4%), together with the

cases of grammar mistakes raised in the corpus,

suggest that grammar needs attention in foreign

language learning.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The results indicate there is a place for teaching

grammar in the process of teletandem learning of

PFL. The deductive approach helped the

systematization of grammatical structures, and

sometimes the inductive approach was more useful.

And the focus on grammar helped the North-

American interactant progress towards a better

command of written and spoken Portuguese.

Further investigation is needed in order to

analyze larger corpora, from several interactants and

perhaps from different target languages, and

investigate the implications of focusing on grammar

for language development in teletandem contexts.

REFERENCES

Almeida Filho, J. C. P.; Oeiras, J. Y. Y.; Rocha, H. V.

1998. Português na internet: questões de planejamento

e produções de materiais (Portuguese on the Internet:

issues of planning and production of materials). IV

Congresso RIBIE, Brasilia, Brazil.

Benedetti, A. M. 2006. O primeiro ano de projeto

Teletandem Brasil [The first year of the Teletandem

Brazil Project.]. Teletandem News, year 1, v. 3, 2006.

http://www.teletandembrasil.org/site/docs/Newsletter_

Ano_I_n_3.pdf.

Brocco, A. S. 2007. The systematization of grammar via a

deductive approach in the teaching/learning of

Portuguese in a teletandem context. Report of a

Scientific Initiation study. Sao Jose do Rio Preto,

Brazil:UNESP, Department of Modern Languages.

Canale. M. 1983. From communicative competence to

communicative language pedagogy. In Richards, J. C.

& Schmidt, R. W. (eds.) Language and

Communication, Harlow:Longman, 29-59.

Custódio, C. M. 2007. Final report on a scientific initiation

project. Sao Jose do Rio Preto, Brazil:UNESP,

Department of Modern Languages.

Cziko, G. A.; Park, S. 2003. Internet audio communication

for second language learning: a comparative review of

six programs. Language Learning & Technology, v. 7,

n.1, 15-27.

Kunzendorf, J. C. 1987. O ensino-aprendizagem de

Português para Estrangeiros adultos em SãoPaulo

(Reflexões - Considerações - Propostas) [The teaching

and learning of Portuguese for adult foreigners in Sao

Paulo (Reflections – Considerations – Proposals). MA

thesis. Sao Paulo, Brazil:Pontificia Universidade

Catolica.

Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult

Learning. San Francisco:Jossey-Bass.

Salomão, A. C. B. É Teletandem ou não? [Is it

Teletandem?] Teletandem News, year 1, v. 3, 2006.

http://www.teletandembrasil.org/site/docs/Newsletter_

Ano_I_n_3.pdf.

Schön, D. A. 1983. How professionals think in action.

New York:Basic Books.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

66