LEARNING THROUGH NFC-ENABLED URBAN ADVENTURE

User Experience Findings

Mari Ervasti and Minna Isomursu

VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Kaitoväylä 1, P.O. Box 1100, FI-90571 Oulu, Finland

Keywords: Near Field Communication (NFC), Mobile learning, Urban adventure track, Context-sensitiveness,

Teenagers.

Abstract: This paper presents a mobile context-sensitive learning concept called the Amazing NFC, and reports the

findings and results of a field study where 228 students experienced the Amazing NFC urban adventure

during spring 2008. The Amazing NFC concept is an Amazing Race -style survival game for teenagers for

learning skills and knowledge essential to everyday life and familiarising them with their hometown. During

the Amazing NFC lessons, students were guided through an urban adventure track with the help of NFC

mobile phone, site-specific NFC tags located at eleven control points and related mobile internet content.

Trial aimed to analyze touch-based interaction paradigm directed to specific users in a defined context as an

implementation technique for mobile learning. User experiences and added value evoked by the service

concept were investigated via a variety of data collection methods. Findings revealed that students

experienced the NFC technology as easy and effortless to use. However, users hoped to see more challenges

and activity in the track in the future. Our analysis indicates that one main benefit of the urban adventure

concept was moving the learning experience from the traditional classroom to a novel context-sensitive

learning environment that includes social interaction between students.

1 INTRODUCTION

Traditional classroom learning is what we are all

most familiar with. It usually awards credits based

on student performance, which is measured through

assignments, tests and exams. Traditional learning

typically takes place in an identifiable classroom

space during pre-defined hours. A classroom usually

has a number of specific features, including a

teacher who delivers information to students and a

number of students who all are physically present in

the classroom and regularly meet at a specific time.

Many learners favour traditional learning while

others find that it is more restrictive and lacks

flexibility. (Learn-Source, 2008)

However, new ways of learning are emerging.

New learning approaches suggest that imaginative

and innovative approaches are needed to bring about

improvements in learning new skills and adopting

new information (Espoir Technologies, 2007). The

best learning occurs in a stimulating, active,

challenging, interesting and engaging environment

when you move at least some part of your body and

when you learn things by doing and by experience

(ibic). The best learning occurs when you are

actively involved in co-constructing knowledge in

your own head, not passively reading or listening or

taking notes. Forcing people to sit in a chair and

listen (or read) dry, formal words (with perhaps only

a few token images thrown in) is often considered to

be the slowest, least effective, and most painful path

to learning (ibid). Yet it is the approach you see

replicated in everything from K-12 to universities.

Mobile phones have now evolved into pocket-

sized computers and as such have the ability to

deliver learning object and provide access to online

systems and services. Mobile learning is unique in

that it allows truly everywhere, anytime,

personalized learning, and offers opportunities to

integrate learning technology into student’s daily

activities (Laroussi, 2004). Mobile devices belong to

a learner’s personal sphere, which means that the

learner can take learning opportunities directly in the

situation where they occur, because the learner has

his learning environment always at hand (ibid).

Mobile learning can also be used to enrich, enliven

or add variety to conventional lessons or courses

(Attewell, 2005). Thus, the educational potential of

55

Ervasti M. and Isomursu M. (2009).

LEARNING THROUGH NFC-ENABLED URBAN ADVENTURE – User Experience Findings.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 55-64

DOI: 10.5220/0001973400550064

Copyright

c

SciTePress

mobile learning contents, both as learning and

teaching tool, is widely acknowledged, and various

initiatives have been undertaken to encourage the

integration of educational mobile resources in school

practice (Avellis et al., 1999).

Portable technologies have been explored in the

context of m-learning to provide literacy and

numeric learning experiences for young adults (aged

16-24) who are not in a full-time education

environment (Attewell, 2005). The m-learning

project running 2001-2004 intended to develop some

of its learning materials using a gaming philosophy

to make their use attractive to young adults. In the

project 62% of learners reported they felt keener to

take part in future learning after trying mobile

learning. 82% of respondents felt the mobile

learning games could help them to improve their

spelling and reading, and 78% felt these could help

them improve their maths. Study’s evidence

suggests that mobile learning can make a useful

contribution to attracting young people to learning,

maintaining their interest and supporting their

learning and development. It was also observed that

loaning equipment to young adults has resulted in

other benefits not directly related to the learning

experience. In particular, some of the learners were

surprised and proud to be trusted with such

expensive and sophisticated technology.

Wyeth et al. (2008) have used mobile technology

as a mediator within science learning activities in a

trial where 11-year-old children completed in pairs

an outdoor treasure hunt activity using a

combination of two mobile phones and a video

camera. During the trial was discovered that all the

children treated the treasure hunt as a competitive

activity and were highly motivated to make

discoveries based on the clues. However, the side

effect of the racing nature of the treasure hunt was

that it detracted from more focused learning and

considered reflections on what had been observed.

Study findings also revealed the importance of

context in learning: new understanding emerged as

children moved through the treasure hunt

environment. Productive and creative aspects

included in the trial appeared also to provide an

intrinsically motivating platform for learning.

Chang et al. (2006), in turn, have introduced the

treasure hunting learning model that extends

Computer-Aided Learning systems from web-based

learning to mobile learning. In their model the

system will provide students suitable instructions or

quests according to students’ learning results on

web, students can use the mobile phone to get the

guidance messages or quiz when they are moving

around in the field, and what concepts students

obtained and did not understand during the mobile

learning phase will be posted on the website in order

to let teacher and students do further discussions.

The effective use of mobile learning resource

depends to a large extent on how enjoyable students

find the learning experience. Some students may be

motivated by an element of competition (Becta,

2006). Also to cater the academic needs of students,

the service needs to be at the appropriate intellectual

level. Avellis et al. (2003) state that the effectiveness

and pedagogical soundness are very important to

evaluate in mobile contents. Some of the factors that

encourage a positive response from students to

mobile learning have been identified as (Becta,

2006):

• Attractive presentation

• Interactivity

• Feedback

• Appropriate skill level(s)

• A 'fun' element

• Clear focus

• Use of different types of media

• Versatility

• Non-threatening environment

• A feeling of progression and achievement

• Intuitive design and interface

• Challenge.

In the Amazing NFC trial, an Amazing Race -

style game was created for teenagers for learning

skills needed in everyday life and learning facts

about the city of Oulu in Finland. An objective was

to trial a context-sensitive educational service for the

target group by utilising NFC technology. Our urban

adventure concept acknowledged the importance of

context within the learning experience by focusing

on situated learning (Brown et al., 1989): enabling

learning in real-life contexts, outside the confines of

a conventional classroom (Tétard et al., 2008).

The aim of the trial was also to investigate user

experiences evoked by the touch-based interaction

paradigm and the mobile learning concept itself. In

addition, the educational aspects concerning the new

learning environment and the suitability of the

touch-based user interface and the related interaction

technique for the target group, i.e. the teenagers was

explored. In the trial was also examined the added

value the concept brings to learning.

2 NFC TECHNOLOGY

Touching with a mobile terminal has been found to

be an intuitive, natural and non-ambiguous

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

56

interaction technique that does not incur much

cognitive load for users (Rukzio et al., 2006).

Välkkynen et al. (2006) state that touching is an

effortless way to select objects in the environment

and it is easy to learn and use.

NFC (Near Field Communication) technology is

designed to make communication between two

devices very intuitive, and NFC suits the

requirements for physical mobile interactions very

well. Objects can be augmented with NFC tags and

mobile devices can be equipped with NFC readers.

Tags in the environment may be used to provide

fast, zero-configuration service discovery (Isomursu

et al., 2008), and they can be attached to virtually

any object or surface. When a tag is touched, the tag

reader integrated into the mobile phone reads the

information embedded by the tag and is then able to

perform predefined actions. Tags are also small and

inexpensive, which makes tags suitable for

embedding the user interface into the everyday

living environment of the user.

The main advantages of NFC are the simple and

quick way of using it and the speed of connection

establishment, and even though people may have to

learn how to use touch-based interaction, it still

offers possibilities to be much simpler and quicker

than classical screen-based user interfaces on mobile

devices (Falke et al., 2007; O’Neill et al., 2007). In

our concept an URL to the web content was

transferred from the tag to the mobile phone when

the user touched the tag. The browser available in

the mobile phone could then directly access the

URL.

3 RESEARCH SETTING

Amazing NFC field trial was implemented in the

city of Oulu in May 2008. The total of 228 students

between the ages of 14 and 15 from the schools

located in the Oulu district participated in the trial.

The mobile learning concept used in the trial was

called “Amazing NFC” after the well-known TV

series called “Amazing Race”. During the Amazing

NFC lessons that took place in downtown Oulu, the

students were guided through an urban adventure

track with the help of mobile phone and related

mobile internet content. Eleven locations, that we

called “control points”, around Oulu were marked

with NFC tags.

In the beginning of the Amazing NFC lesson, the

students were grouped into small groups of two.

Each student was provided with Nokia 6131 NFC-

enabled mobile phone for the duration of the lesson

and each student pair received an individual route

with a designated departure point. Upon arrival at a

control point, the student touched the NFC tag and a

web-page concerning information about the place

where the control point was located (e.g. a museum)

was sent to the student’s phone. First the student

read the text relating to the control point, watched a

video or listened to an audio file, and then answered

to a question related to the site. In some locations,

the question required the user to do some tasks to

acquire the information needed to answer the

question. After completing the assignment, students

received instructions and a map guiding them to the

next NFC control point. The control points, with the

exception of zoological museum, were located in the

city centre within a couple of kilometres distance,

and the students were expected to travel from one

control point to another with bikes (although some

used mopeds against instructions).

During the lesson, the teachers were able to

follow in real time via a web-based user interface

how the pairs of students proceeded through the

adventure track. Also, the students were advised to

use the mobile phone to call the teacher in case of

problems or questions. In Figure 1 is described the

overall view of the urban adventure concept.

Figure 1: Overall view of the trial.

The educational goals of the Amazing NFC

lesson were to provide the students with knowledge

related to landmarks, public buildings and offices in

their hometown, and practical skills related to

dealing with public authorities in mundane everyday

tasks. The locations chosen as control points were

city information centre, fire station, swimming hall,

LEARNING THROUGH NFC-ENABLED URBAN ADVENTURE - User Experience Findings

57

police station, museum, city hall, youth and culture

centre, zoological museum at University of Oulu

(requiring a bus journey to the museum and back,

and ticketing was done with an NFC phone), city

library, theatre and the social insurance institution.

During the bus journey to zoological museum, the

students became familiar with, among other items,

the “Initiative for Oulu” service, i.e. sending an

electronic initiative to city authorities by touching

information tags in the bus. In Figure 2 the student is

touching the Amazing NFC tag at the control point

inside the social insurance institution.

Figure 2: Student visiting the Amazing NFC control point

located at the social insurance institution.

The Amazing NFC lesson was planned and

designed in close cooperation of teachers, service

and technology providers, and researchers. During

the design phase was especially emphasised the

ultimate goal of integrating the concept into the

normal practices of the schools, so that the trial

would not to remain as a single occasion related to

the research project. The aim was to create a viable

concept that could be adopted as a learning

instrument to be used also after the research trial.

This required tight involvement of teachers and

school administration in planning and implementing

the applications, and organizing and supervising the

trials. During the trial, the researchers were only

involved in the data collection activities; teachers

took full responsibility for organizing and

supervising the actual Amazing NFC lessons.

4 DATA COLLECTION

Dutton and Aron (1974) have stated that humans are

not very good at analysing what actually caused an

experience, so it can be difficult for users to identify

if the experience was caused by the technology

under evaluation or the user experience evaluation

method (or any other event in the life of the user).

Human memory about experiences is also unreliable

thus affecting our ability to recall past experiences

so that we could compare them with other

experiences (Schooler and Engstler-Schooler, 1990),

or to describe them reliably after time has passed.

Also, our ability to predict our own experiences in a

hypothetical or future setting is very limited (Wilson

et al., 2000; Gilbert and Wilson, 2000). Therefore, in

order to achieve the most reliable understanding of

user experience, the data during the Amazing NFC

lessons was collected in three phases: before use,

during use and after the use.

Since describing and understanding user

experience are complex as user experience is always

multifaceted and difficult to verbalise and describe,

the combining of different data collection methods

increases the reliability and validity of the results

(Isomursu et al., 2007). Therefore, we decided to

utilise a variety of data collection methods that were

highly complementary (Yin, 2003). The methods

used and data collected in different phases of the

experiment were as follows.

Before the start of the trial, two teachers were

interviewed in order to investigate their

expectations, doubts, thoughts and attitudes towards

the evaluated technology and learning concept.

Before the Amazing NFC lesson we also observed

how the students learned to use NFC technology,

and what kind of spontaneous reactions and

discussion took place in introduction of the concept.

A mobile questionnaire was used to capture

information about the expectations and attitudes

towards the mobile learning experience before the

lesson. Unfortunately, there were some technical

problems with the mobile questionnaire during the

very first trial lessons. Additionally, some teachers

forgot to provide the NFC tag used for accessing the

mobile questionnaire for their students. Therefore,

not all students were able to report their experiences

through the mobile questionnaire (we received 133

valid responses from 228 participants).

User experiences during the Amazing NFC

lesson were collected through video recordings, and

through automatic creation of log data about how the

pairs of students progressed on the track. Video

recordings were made by placing video cameras at

fixed spots to record students while they were

visiting the NFC control points, and by providing

students video cameras that they could use to record

their experiences during the lesson.

After use, the students filled out a second mobile

questionnaire collecting data about the user

experience immediately after use. The data received

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

58

from both mobile questionnaires was used to survey

how students’ expectations and attitudes changed

during the trial; whether their expectations were met

and attitudes altered. The students and teachers were

also requested to fill out a web questionnaire within

two weeks after the trial. For this purpose we created

two separate questionnaires (resulting in a total of 81

responses from students and 8 from teachers). In

addition, we arranged a workshop with twelve

students to explore the experiences with the

Amazing NFC. The workshop included participatory

features, i.e. the students participated in designing

how to iterate the concept for future use.

5 FINDINGS

5.1 Before Use

Evaluation before use was done for gaining insights

into the attitudes, expectations and doubts of the user

groups regarding the upcoming Amazing NFC

lesson. Technology training situation was observed

to see how the students coped with learning to use

new touch-based interaction technique.

5.1.1 Interviews with Teachers

In general, teachers had a positive attitude toward

the learning concept. They found the trial

trustworthy; students could not get lost or get into

trouble as the teachers could follow their progress on

the track in real time through a web interface and

contact them if needed. Teachers felt it was good

that learning could be taken out from the traditional

classroom and 45-minute teaching style. They saw

the concept as an excellent way to familiarise the

students with their hometown and for students to

learn life-skills and to gain more courage to visit

different public buildings and offices in the city.

However, teachers thought that urban adventure

track needs to provide students a sufficient amount

of challenge in order to maintain their interest and

motivation during the Amazing NFC lesson. Thus,

in order to make a concept to succeed and to create

real experiences students must be offered more

activities, such as competitions and tasks. Teachers

expressed a doubt of NFC technology having the

taint of decoration; that in practice NFC would not

bring any added value for the learning concept.

Teachers’ stressed that the technology itself is not

enough to surprise and amaze students; it is the

content and activities that need to generate real

experiences.

5.1.2 Observation of the Training

Before the Amazing NFC lesson, students were

given an introduction to NFC technology and they

had their first visual and physical encounter with the

learning concept and their first hands-on experience

on using the novel interaction paradigm. Therefore,

it is not surprising that learning touch-based

interaction required some practicing. Students

needed some practice to find the comfortable

personal reading distance between the tag and the

phone. Also, finding the right touching spot both

from the phone and from the tag, and learning the

response times required some practice. However, as

teenagers are nowadays very technological-savvy

and familiar with mobile technology, they adopted

the new technology and touch-based interaction fast:

all students were able to learn to use touch-based

interaction with a few repetitions.

5.1.3 Mobile Questionnaire

Students’ preliminary feelings were explored with a

mobile questionnaire just before the Amazing NFC

lesson: general attitudes toward the lesson, the

biggest expectations of and the major doubts about

the lesson. We received 133 responses from 74 boys

and 59 girls. A three-point Likert scale ranging from

1 (positive) to 3 (negative) was used to measure the

question concerning the attitude. 54.1% of students

had positive feelings about participating in the

lesson, and only 10.5% of students expressed

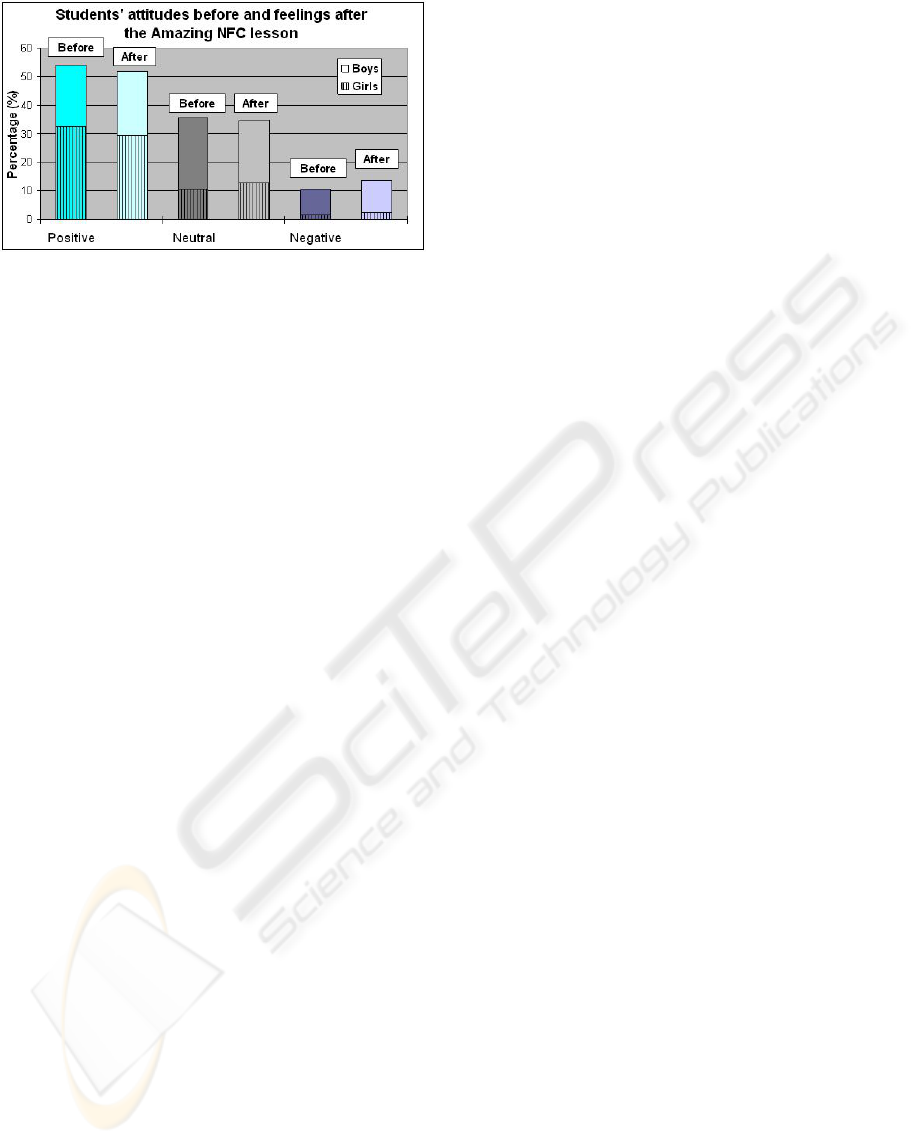

negative attitudes towards the lesson (see Figure 4).

In order to investigate the correlations that

stemmed from the student’s gender, data was also

analysed by doing the dependency tests between the

questionnaire parameters. Between the student’s

gender and attitude towards the Amazing NFC

concept was found a direct correlation (see Figure

4). 16.2% of boys had negative attitudes towards the

lesson, whereas only 3.4% of girls expressed the

same opinion. In contrast, 72.9% of girls thought it

was nice to attend the lesson, the corresponding

proportion of boys counting only to 39.2%.

Students were expecting most eagerly (see

Figure 3) to spend time with their friend (21.8%), to

try out new technology (21.8%) and to get out of the

school (19.5%). They were least expecting to learn

new information at the control points (9.8%) and to

get to know new places (8.3%). Correlation was also

discovered between the gender and expectations

(Figure 3). 32.2% of girls were most expecting

spending time with their friend while only 13.5% of

boys were expecting that. Whereas 29.7% of boys

and only 6.8% of girls were expecting getting away

LEARNING THROUGH NFC-ENABLED URBAN ADVENTURE - User Experience Findings

59

from school the most. Quite surprisingly, more boys

(13.5%) than girls (5.1%) were waiting “learning

new information”, whereas girls (15.3%) were more

waiting “getting to know new places” when

compared to boys (2.7%).

Figure 3: Students’ expectations of the Amazing NFC

before the lesson (n=133; 74 boys and 59 girls).

Over half of the students (66.2%) reported

having no doubts regarding the Amazing NFC

lesson. Of those 33.8% students that reported having

some doubts, 16.5% identified the most important

reason to be the anticipated problems with new

technology, 7.5% considered it to be the difficulty of

finding the control points and moving around the

city and 3.8% feared bad weather during the day.

Student’s gender had also effect on whether or not

something daunted him or her before the lesson:

41.9% of boys had some doubts whereas the figure

with girls was lower (23.7%).

5.2 During Use

Collecting information about user experiences at the

time they happen requires in situ data collection

methods which can be applied during the use of

technology (Consolvo et al., 2007). This means that

the tools and methods used for collecting user

experience data need to be integrated into the

everyday practices of the trial users, just as the

technology under evaluation. Experiences show that

the user experience evaluation method may actually

“steal the show” (Isomursu et al., 2007) if it is more

visible and needs more attention and cognitive

processing from the user than the actual technology

under evaluation.

5.2.1 Video Recording

Video cameras were set at fixed spots to record

students while they visited NFC control points. This

solution was chosen in order to minimise the

interruption of the videotaping, and to prevent it

from having an influence on the user’s behaviour

and user experience formation (Yin, 2003).

However, when the student’s head was down while

he was watching the mobile device, it was difficult

to see all the facial expressions. Students also often

turned their backs to the camera or even moved out

of the reach. Thus, videos recorded by students

themselves proved to be a better information source.

Videos showed, for example, that students

commonly asked for help from passers-by if they

had trouble finding the control points. During the

lesson they also called and send text-messages to

their classmates to find out how they were doing and

how many control points they still had to go.

5.2.2 Log Data

User experiences were also collected by monitoring

the log data that was automatically recorded from

the control points by the Amazing NFC backend

system. For example, from the log data could be

seen that some pairs coincided with each other at

some control point and continued their way from

then on together, which resulted in some students

going through part of the track in bigger groups.

5.3 After Use

After-use evaluation was utilised to investigate user

experiences after the lesson and to identify possible

changes in students’ attitudes by comparing

situations before and after use. Also the future use of

the concept was inquired of students and teachers.

5.3.1 Mobile Questionnaire

Students’ experiences were explored with a mobile

questionnaire immediately after they had finished

the Amazing NFC lesson. The questionnaire

explored the general feelings after the lesson as well

as the best things and the downsides experienced

during the lesson. A three-point Likert scale ranging

from 1 (positive) to 3 (negative) was used to

measure the question concerning the emotions.

51.9% of the students reported that they had enjoyed

participating in the lesson, whereas 13.5% described

their feelings as negative (see Figure 4). A direct

correlation between student’s gender and feelings

after the lesson was revealed: 20.3% of boys had

negative feelings when only 5.1% of girls were in

the same opinion. As much as 66.1% of girls but

only 40.5% of boys had enjoyed the lesson.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

60

Figure 4: Students’ attitudes towards Amazing NFC

before the lesson and their feelings towards Amazing NFC

after the lesson (n=133; 74 boys and 59 girls).

There was also discovered correlation between

students’ attitudes before and feelings after the

lesson. 60% of the respondents who reported having

negative feelings after the lesson had also had an

unfavourable attitude towards the lesson.

Correspondingly, as much as 72.9% of those having

positive feelings after the lesson had also had a

favourable, positive attitude before the lesson.

The best things in the lesson were considered to

be spending time with a friend (30.8%), wandering

on the town (22.6%) and trying out new technology

(19.5%). Over half of the students (64.7%) stated

that in their opinion there were no downsides in the

Amazing NFC lesson. Those 35.3% that had

experienced some negative things felt that the most

important reason was related with finding the control

points and moving around the city (12.8%).

5.3.2 Web Questionnaires

After the trial, students and teachers answered to the

web questionnaire that aimed for evaluating their

experiences about the lesson and finding

improvement ideas for Amazing NFC. Unless stated

otherwise, a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1

(strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) was used to

measure the questionnaire variables.

The total of 81 students (42 girls and 39 boys)

answered to the web questionnaire. The majority of

the respondents reported that they liked the urban

adventure track (av. 3.741, where the scale was from

1 (boring) to 5 (nice)). Students mostly agreed that it

was easy (av. 1.691) to discover the tags located at

the NFC control points. The navigation from one

control point to other by using the map and

instructions received on the mobile phone was

considered easy (av. 1.838). The usage of NFC

phone and touching the tags was also experienced as

effortless and natural (av. 1.457).

However, the students somewhat disagreed (av.

2.432) that the information provided at the control

points was interesting. Students did not think they

had learned lot of useful information during the

lesson (av. 2.346) nor considered the questions

presented at the control points having been

challenging (av. 2.951). Nevertheless, they preferred

(av. 1.704) the learning through Amazing NFC to

learning in the classroom, but did not think (av.

2.346) that participating in the trial had given them

more courage to visit the public buildings and

offices in their hometown.

Students found it nice (av. 1.469) that they could

go from one control point to other on their own and

at their own pace. In the trial, the learning

experience was rather social, as the students were

instructed to work in pairs. Working in pairs was

preferred by almost all (97.5%). In addition, many

participants (59.5%) reported that they had formed

bigger groups during the Amazing NFC lesson. The

time it took from the students to go through the

adventure track and the distances between the

control points were perceived as suitable by 76.5%.

In the web questionnaire were also explored

students’ preferences between the eleven control

points. Students had most liked about the control

point that was situated inside the zoological museum

(32.1%), next best was the bus journey to the

museum (25.9%), the third best being the police

station (9.9%). So, clearly the most interesting

control point for Amazing NFC participants was the

visit to zoological museum. The visit started with a

bus journey, where the students were able to use

their NFC phones for ticketing. Inside the bus the

students were able to use informational NFC tags

offering e.g. news from the local newspaper. For

other transitions, students used bikes in all weathers.

During some lessons, weather was cold, rainy and

windy. Also, as the lesson lasted approximately

three hours, some students started to get tired.

Therefore, the bus ride was experienced as a

welcome change. At the zoological museum, the

students were instructed to see the animals on

display, and consume content about the animals

through tags attached to the displays. When

compared to other control points, there was clearly

required more activity and offered more interaction

with the environment.

Students reported that they would be willing to

participate in the Amazing NFC lesson also in the

future (av. 2.123), but were not especially eager to

go through the adventure track on their own outside

the school (av. 2.716). In students’ opinion NFC

technology suited the learning concept well (av.

LEARNING THROUGH NFC-ENABLED URBAN ADVENTURE - User Experience Findings

61

1.605) and they would be glad (av. 1.815) to use

NFC technology also in other situations and

environments. The average grade students gave to

the concept was 8, on a scale from 4 to 10.

The total of eight teachers answered to the web

questionnaire after the Amazing NFC lesson.

Teachers experienced that the new learning concept

exceeded their expectations (av. 1.5) and somewhat

agreed that students had learned and received new

information to expected extent (av. 1.75). All the

teachers thought that the adventure track served well

getting to know ones hometown, and 75% of the

teachers were in the opinion that the lesson had also

served students becoming independent and learning

life-skills, whereas only 25% thought that the lesson

had served informational learning. They also agreed

that the monitoring of students’ progress on the track

was easy (av. 1.375) through the web-based

interface and had received all the necessary

information through it (av. 1.625). All the teachers

were ready to exploit the learning concept in the

future. The average grade the teachers gave to the

concept was 8.9 on the scale from 4 to 10.

Teachers gave also many ideas for the future

utilisation of Amazing NFC concept. For example,

different kinds of adventure tracks could be planned

based on art works, nature, history or different

theme days such as Easter and Christmas, and in

those occasions tags could be placed in locations

that suit the theme. Teachers also hoped to see the

concept to be used for teaching of different school

subjects, e.g. in language learning clues and tasks at

the control points could be given in English. NFC

tracks could also be created for new students starting

the secondary school in autumn. On their first day at

new school students could go through the adventure

track located on the school premises and would thus

have an opportunity to familiarise themselves with

the new school and its surroundings. Getting to

know unfamiliar cities with the help of NFC

technology would also be useful for example during

school trips. Teachers were in the opinion that the

adventure track should be mainly directed for a bit

younger students, because students around the age of

15 already have so advanced knowledge and skill

levels that they comprise a difficult target group

when you want to dazzle them with new

information.

5.3.3 Workshop

In the workshop twelve students were asked to give

ideas on how the Amazing NFC concept could be

improved and developed further. In their opinion,

tags at the control points should be hidden and

located in more difficult places. Students also

thought that the tasks should be longer, and more

effort should be required to find answers to

questions, because now all just guessed the answers.

There should be someone supervising at the control

points to check that all tasks would be performed

correctly. Students hoped to see more physical and

problem-solving tasks and activities at the control

points and if they could also compete with each

other on the adventure track it would bring along

more motivation and excitement.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

The Amazing NFC learning concept provides a

learning experience on a mobile phone – which

many young people are comfortable using and

enthusiastic about. Mobile technology was used to

encourage both independent and collaborative

learning experiences, to help to battle against

reluctance to use ICT in learning, to help to remove

some of the formality from the learning experience,

to engage reluctant learners, to aid learners to remain

more focused for longer periods and to help to raise

learners’ independence and self-esteem. In our

concept an objective was to have learning content,

pedagogical methods and technological tools all

functioning in a harmony (Tétard et al., 2008).

Teenagers are a tough target group for designing

mobile services. The experience and high knowledge

in using mobile devices means that this user group is

hard to amaze or even satisfy. NFC promises a novel

and intuitive user interface to mobile devices but the

novelty of the technology is not enough to ensure the

success and interest of the concept. The teenagers

who attended the trial had high expectations

concerning the new technology and the content and

quality of the service. One factor contributing to

negative attitude towards the content provided and

related tasks may be the association made by naming

Amazing NFC after the popular TV show “Amazing

Race”. The naming might have set expectations and

mental impressions that were not fulfilled. For

example, searching and finding the tag at the control

points was part of the excitement of the urban

adventure. This is illustrated in the following

improvement idea expressed by one of the students:

“Tags should be somehow hidden so it would be

more interesting to search for them.” The

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

62

excitement and challenge level of the TV show was

not obviously reached during the lesson.

Observation of students showed that none of

them had problems in learning to use touching as an

interaction technique within a couple of minutes of

hands-on training. Intuitiveness and naturalness of

this interaction technique made adopting effortless.

In NFC technology survey (O’Neill et al., 2007) was

discovered that users were concerned with how the

use of NFC readers in public spaces made them

appear to other people around them. Many

participants of that survey noted that they felt

awkward at first using NFC due to the very explicit

public act of reaching out and touching a tag

embedded in the environment. However, many

participants lost their reservations about using NFC

over the course of the trial. In Amazing NFC trial,

none of the students reported that touching tags

would make them feel uncomfortable.

Even though the students attending the Amazing

NFC lessons mostly reported that context-based

mobile learning experience was better than

classroom learning and they enjoyed participating in

the lesson, they criticized the provided content

strongly. Majority of students reported that the tasks

and the information provided were not interesting

and challenging enough to make the urban adventure

truly motivating and thrilling. Students expressed

their need for getting more challenging tasks, for

example by including physical and competitive

activity and increasing the variety of tasks. For

example, the following student comment reveals the

need for improvement: “There should be more

challenge at control points. Now the maps were not

actually needed and the questions were too easy.”

Clearly the most interesting control point for

Amazing NFC participants was the visit to the

zoological museum. When compared to other

control points, there was more activity required from

the students and more interaction offered with the

environment. The average time used for the visit was

the longest during the lesson, and the content and

related questions integrated seamlessly with the

physical activities required and the context of use. In

most control points, the students just quickly visited

the entrance hall of a public building for reading the

content and to answer the question. In these cases,

the physical experience and social context of the

location did not successfully integrate with the

content provided, as the students did not really

interact and experience the space and environment

they visited.

Thus, in future development the Amazing NFC

urban adventure needs to be more carefully

combined with intrinsically motivating attributes

(Malone and Lepper, 1987) such as challenge,

curiosity and competition. However, when adding

the element of competition in learning, one has to be

aware of the possible pitfalls associated with racing

(Wyeth et al., 2008).

Teachers brought up an idea that in the future the

students themselves could act as content creators and

providers by offering them a possibility to create

their very own tags and to place these tags at the

control points. In general, teachers identified that the

main benefit of the Amazing NFC lesson was

moving the teaching situation and learning

experience from the traditional classroom to real-life

contexts that also included social interaction

between students.

Within this mobile learning concept the threats

mostly concern to ensure the safety of students while

they are independently going through the urban

adventure track. However, students participating in

the trial were already older and more independent

and used to move around the city by themselves.

Also, students could not get lost in the city because

teachers were able to follow in real time their

progress on the track through a web interface, and

the students were advised to use the NFC phone to

call the teacher in case of problems or questions.

Throughout the pilot, the students coped very well

on their own. However, the city of Oulu is relatively

small (130 000 inhabitants). In bigger cities safety

could be more of a problem.

Also, in this kind of concept a password

protection is a necessary requirement to gain access

to the web interface that contains status information

of the students (which control points have been

visited, at what time and by whom) while they are

on the urban adventure track. Tags at the control

points need also be protected against rewriting.

After this Amazing NFC trial, the project

arranged a cultural/historical track where students

became familiar with the city of Oulu’s culture and

history. The route consisted of seven NFC control

points located at the local cultural and historical sites

in the Oulu, such as statues, monuments and

historically meaningful buildings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the students and teachers of

the participating schools. We are also grateful to the

administrative units of the city of Oulu for being

actively involved in this mobile learning pilot

scheme. This work was done in the SmartTouch

LEARNING THROUGH NFC-ENABLED URBAN ADVENTURE - User Experience Findings

63

project (ITEA 05024) which is a project within

Information Technology for European Advancement

(ITEA 2), a EUREKA strategic cluster programme.

The SmartTouch project (www.smarttouch.org) has

been partly funded by Tekes, the Finnish Funding

Agency for Technology and Innovation.

REFERENCES

Attewell, J., 2005. Mobile technologies and learning – A

technology update and m-learning project summary.

Technology Enhanced Learning Research Centre.

Learning and Skills Development Agency.

Avellis, G., Capurso, M., 1999. ERMES evaluation

methodology to support teachers in skills

development. In Proceedings of Conference on

Communications and Networking in Education:

Learning in a Networked Society, pp. 12-19. Springer.

Avellis, G., Scaramuzzi, A., Finkelstein, A., 2003.

Evaluating non-functional requirements in mobile

learning contents and multimedia educational

software. In Proceedings of European conference on

Mobile Learning (MLEARN). University of

Wolverhampton, UK.

Becta, 2005. Introduction to user needs in designing e-

learning resources. Last access 09.12.2008. URL:

industry.becta.org.uk/content_files/industry/resources/

Key%20docs/Content_developers/intro_userneedsdesi

gn.doc

Brown, J.S, Collins, A., Duguid, P., 1989. Situated

Cognition and the Culture of Learning. Educational

Researcher, 18(1), pp. 32-41. SAGE Publications.

Chang, A., Chang, M., Hsieh, A., 2006. A Treasure

Hunting Learning Model for Students Studying

History and Culture in the Field with Cellphone. In

Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on

Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT’06), pp.

106-109. IEEE Computer Society.

Consolvo, S., Harrison, B., Smith, I., Chen, M.Y., Everitt,

K., Froehlich, J., Landay, J.A., 2007. Conducting in

situ evaluations for and with ubiquitous computing

technologies. International Journal of Human-

Computer Interaction, 22(1-2), pp. 103–118. Taylor &

Francis.

Dutton, D.G., Aron, A.P., 1974. Some evidence for

heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high

anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 30(4), pp. 510–517. American

Psychological Association.

Espoir Technologies, 2007. Scientific Reasoning in Plain

English – Passion-based Learning. Last access

09.12.2008. URL: http://espoirtech.com/SR.pdf

Falke, O., Rukzio, E., Dietz, U., Holleis, P., Schmidt, A.,

2007. Mobile Services for Near Field Communication.

Technical Report. University of Munich, Department

of Computer Science, Media Informatics Group.

Gilbert, D.T., Wilson, T.D., 2000. Miswanting: some

problems in the forecasting of future affective states.

Feeling and Thinking: The Role of Affect in Social

Cognition. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Isomursu, M., Isomursu, P., Horneman-Komulainen, M.,

2008. Touch to Access Mobile Internet. In

Proceedings of OzCHI. ACM Press.

Isomursu, M., Tähti, M., Väinämö, S., Kuutti, K., 2007.

Experimental evaluation of five methods for collecting

emotions in field settings with mobile applications.

International Journal of Human Computer Studies,

65(4), pp. 404-418. Elsevier.

Laroussi, M., 2004. New e-Learning Services based on

Mobile and Ubiquitous Computing: UBI-Learn

Project. In Proceedings of International Conference

on Computer Aided Learning in Engineering

Education (CALIE).

Learn-Source, 2008. Forms of Learning. Last access

09.12.2008. URL: http://www.learn-

source.com/education.html

Malone, T.W., Lepper, M.R., 1987. Making Learning Fun:

A Taxonomy of Intrinsic Motivations for Learning. In

Aptitude, learning, and instruction: Cognitive and

affective process analyses. Erlbaum. Hillsdale, NJ.

O’Neill, E., Thompson, P., Garzonis, S., Warr, A., 2007.

Reach Out and Touch: Using NFC and 2D Barcodes

for Service Discovery and Interaction with Mobile

Devices. In Proceedings of PERVASIVE 2007, pp. 19-

36. Springer-Verlag.

Rukzio, E., Leichtenstern, K., Callaghan, V., Schmidt, A.,

Holleis, P., Chin, J., 2006. An experimental

comparison of physical mobile interaction techniques:

Touching, pointing and scanning. In Proceedings of

The 8th International Conference on Ubiquitous

Computing (Ubicomp 2006), pp. 87-104. Springer.

Schooler, J.W., Engstler-Schooler, T.Y., 1990. Verbal

overshadowing of visual memories: some things are

better left unsaid. Cognitive Psychology, 22(1), pp.

36–71. Elsevier.

Tétard, F., Patokorpi, E., Carlsson, J., 2008. A Conceptual

Framework for Mobile Learning. Research Report

3/2008. Institute for Advanced Management Systems

Research.

Välkkynen, P., Niemelä, M., Tuomisto, T., 2006.

Evaluating touching and pointing with a mobile

terminal for physical browsing, In Proceedings of the

4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer

interaction: Changing Roles, pp. 28-37. ACM Press.

Wilson, T.D., Wheatley, T., Meyers, J.M., Gilbert, D.T.,

Axsom, D., 2000. Focalism: a source of durability bias

in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 78(5), pp. 821–836. American

Psychological Association.

Wyeth, P., Smith, H., Ng, K.H., Fitzpatrick, G., Luckin,

R., Walker, K., Good, J., Underwood, J., Benford, S.,

2008. Learning through Treasure Hunting: the Role of

Mobile Devices. In Proceeding of the IADIS

International Conference Mobile Learning. IADIS.

Yin, R.K., 2003. Case Study Research: Design and

Methods, Sage Publications. London, 3rd edition.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

64