A CULTURE OF SHARING

A Look at Identity Development Through the Creation and Presentation

of Digital Media Projects

Caitlin Kennedy Martin, Brigid Barron

Stanford Center for Innovations in Learning, Stanford University, Stanford, California, U.S.A.

Kimberly Austin, Nichole Pinkard

University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.

Keywords: Identity, Project-based learning, Technological fluency, Media design, Case study.

Abstract: We share two longitudinal case studies of thirteen-year-old students who were part of a design intervention

focusing on media production and technological fluency, tracking how project production and presentation

developed students’ sense of themselves and their reputation within the community. Practices supporting

positive academic and creative identity development are highlighted.

1 INTRODUCTION

We believe that there is a need for theory that

specifies practices to support not only the

development of interest in learning (Hidi &

Renninger, 2006) but positive academic and creative

identities, as well. In this paper we look at youth

production and presentation within a technology and

media rich school environment and how

opportunities and affordances within the

environment influenced student identity

development. Our specific research questions

include: (1) How does presentation and sharing of

work support students’ identity development as they

take on meaningful roles in production, access

domain knowledge, share and receive community

attention? (2) What practices within the environment

support the development of different positive

identities, including that of new media creator?

Recent theoretical perspectives on identity

development seek to move beyond static and

singular conceptions of identity, typically cast in

terms of demographic variables such as gender, age

and ethnicity. Penuel & Wertsch (1995) argue that

identity formation involves an encounter between

cultural resources for identity and individual choices

with respect to particular commitments. Gee (2000)

distinguishes nature identity, institutional identity,

discourse identity, and affinity identity and argues

that identity can shift across contexts or time. Nasir

& Saxe (2003) provide an analytical approach that

helps us understand how the social environment

positions students as particular types of community

members.

Developing, presenting and sharing technology

projects and experiences within a collaborative

community of people with similar interests/ideas is

recognized as one way for youth to develop a sense

of their own identity, role, and position within the

new media culture. In his 2006 position paper,

Henry Jenkins addresses the importance of sharing

as part of a digital community, maintaining that the

new definition of technological fluency involves

youth taking part at various levels in continuous and

widening cultures of technology and media creation

and involvement. Examples of this type of

participatory culture range from simply being a part

of an online community, to producing new media

projects, to collaboratively developing and sharing

new media, goals, and messages. Other researchers

have noted the potential of participation in these

types of environments as a way for youth to develop

a sense of their role within the community. Peppler

and Kafai (2007) documented youth who

participated in a Community Technology Centre

gaining new understandings of what it means to be a

designer, including choice of appropriate tools,

167

Kennedy Martin C., Barron B., Austin K. and Pinkard N. (2009).

A CULTURE OF SHARING - A Look at Identity Development Through the Creation and Presentation of Digital Media Projects.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 167-174

DOI: 10.5220/0001978101670174

Copyright

c

SciTePress

finding resources, critiquing their own work and that

of others, getting feedback, and revising.

In our analysis, we build on these theoretical and

methodological insights in the service of advancing

our understanding of how a school-based technology

learning environment supports identity formation as

authors, designers, and creative new media artists

and critics.

1.1 Context and Methods

Data collection takes place at Renaissance Academy,

a middle school serving approximately140 students

grades sixth through eighth (i.e., ages 11 to 14 years)

in a large, urban area in the Midwest region of the

United States. The school has a partnership with the

Digital Youth Network (DYN), an organization

intended to develop students’ “new media literacy,”

(Pinkard et al., 2008). Opportunities for presentation

are considered important and are built into the

program. The DYN programmatic structure contains

formal and informal learning spaces, including: (1)

mandatory weekly media arts classes offered during

the school day; (2) eight weekly after school clubs

called “pods,” including digital design, digital

music, digital radio, digital video, digital queendom

(a girl’s only space), spoken word, video game

design, and robotics; (3) weekly after school forums;

(4) Remix World, an online social networking site

that complements face-to-face participation by

creating additional spaces for project development,

presentation, and critique; and (5) unstructured time

to use the program’s production tools. While all

students attended yearlong media arts classes, the

other DYN components were voluntary.

Approximately 50 students regularly attended at

least one after school pod each week.

Data collection occurred during two academic

school years, 2006-07 and 2007-08. We are in the

final year of a three-year study documenting the

learning and development of nine focal case students

within

DYN who began sixth grade in the fall of 2006.

We use both interview and field note data to create

portraits of learning about technology across time and

setting in a genre that has been called technobiography

in recent work (Henwood, Kennedy, & Miller, 2001).

1.1.1 Interviews

Interviews with students at multiple time periods and

adult teachers and DYN coordinators were recorded

and transcribed.

Learning Ecologies Interview. A semi-structured

interview protocol was developed to obtain detail on

how computers were used at home, school, with

peers, on-line, and through community based

contexts. There were three main sections of the

interview: (1) How students used and learn about

technologies in the contexts of home, school,

friend’s houses, and community locations; (2) how

students see themselves in relation to new

technologies; and (3) interests and future plans. Each

interview was conducted by one interviewer with

one student in a private room and was recorded with

both a digital audio recorder and a video camera

when possible. Interviews varied in length from 30

minutes to over an hour. All case learners were

interviewed in December of their sixth grade year.

Artefact-based Interview. This semi-structured

interview was designed to provide a focused look at

the projects students are working on and obtain an

account from the learner’s perspective of how they

learned, how the projects came to occur (pathway),

and the opportunities for fluency building within

different projects. Questions primarily focused on

their stories of creation and learning. Two

researchers interviewed each student in a private

room at school with student work displayed on their

laptops. Interviews lasted approximately one hour

and were video-recorded with the camera focused on

the screen and keyboard to capture the visual

referent of the interviewee. All case learners were

interviewed at the end of sixth and seventh grade.

Teacher and DYN Coordinator Interviews.

During an offsite professional development

workshop, eight teachers and coordinators

participated in three 15-30 minute semi-structured

interviews about a case learner. Prompts were

designed to elicit adult perceptions of the cases as

learners, producers/creators, collaborators, and

members of the DYN community. All interviews

were audio-recorded.

1.1.2 Field Notes

Three researchers observed more than 195 hours of

the 45-minute classes and 2-hour after school

sessions. Researchers focused on: (1) instructional

delivery, (2) opportunities for production and

presentation, and (3) adult and youth interactions

around instruction and creation. While in the field,

researchers prompted participants to explain

decision-making related to teaching and production.

We recorded events as descriptive “episodes” in

effort to maintain the real-time sequencing of events

(Emerson, Fretz & Shaw, 1995). Lastly, researchers

collected audio and video recordings as well as

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

168

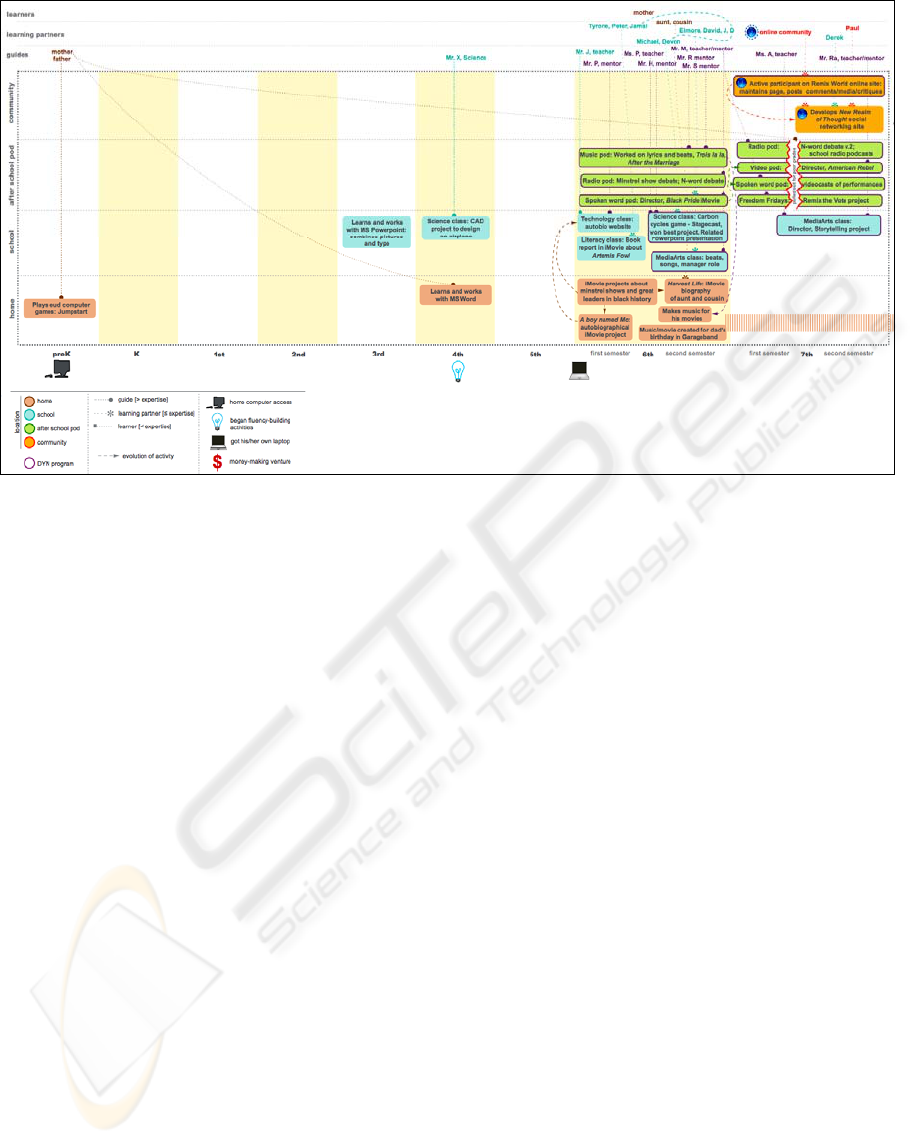

Figure 1: Technobiographical timeline representation for Maurice, with key.

artefacts. Researchers conducted line-by-line coding

(Emerson, Fretz and Shaw, 1995) of these notes

using broad categories. The third author reviewed

the application of these codes in order to refine the

schema. Using this revised coding plan, the notes

were re-examined and coded as event segments

whereby changes in group membership, instructional

format, locations, discontinuity of time, and

instructional topics of materials formed the frame for

applying codes (Stodolosky 1988). The researchers

used the output from this coding to identify patterns

in student identity develop within the learning

context.

2 RESULTS

In the DYN classes and pods, coordinators used a

project-based approach to encourage the acquisition

of digital literacy skills. Project work often involved

students taking on specific design and production

roles. In DYN during-school classes, students were

sometimes assigned roles or were allowed to choose

from a list of responsibilities needed to complete the

assigned project work. This format supports student

identity development within a set of defined new

media production roles. The more informal DYN

spaces, including the after school pods and the remix

world online social networking site, provided

opportunities for students to independently pursue

their own projects and come up with new and

innovative roles for themselves. Across classes,

pods, and online spaces, the public sphere of

presentation motivates creation but also fosters

identity emergence and saliency via the acts of

invitation, performance and discussion, and the

recognition through competition and evaluation.

Below we share two cases that highlight identity

development within the context of project creation

and presentation in DYN. More generally we look at

how this environment and certain practices within it

contribute to or detract from the positioning of

students as creative media producers.

2.1 The Social Change Activist

Maurice was an outspoken student in the DYN

community who used his digital media expertise to

share messages and ideas, which frequently involved

African American history and pride. He participated

in the radio and music pods in sixth grade and the

video and radio pods in seventh grade. His timeline

reflects his growing technology skill set and project

portfolio (see figure 1). By the end of seventh grade

Maurice had developed at least six substantial video

projects, five music projects, three radio packages

(podcasts), and an online social networking website

titled wechange. Maurice saw himself as a unique

individual who was capable with technology and by

the end of seventh grade most of the DYN

community seemed to agree. DYN coordinators

referred to him as “innovative” and “creative” and

A CULTURE OF SHARING - A Look at Identity Development Through the Creation and Presentation of Digital Media

Projects

169

his peers often looked to him for help. His project

work and visibility were instrumental in his personal

identity development and the formation of his

reputation within the larger community.

2.1.1 Visibility of Self in Project Production

One way that Maurice shaped his identity as a

producer and creator was to clearly document his

roles. His video work often included a credits

section listing his contributions, such as “Video

director” and “Visuals director.” He consistently

used a radio DJ name for his podcasts in the radio

pod. The “About me” section of his wechange social

networking site profile read simply, “I am the

Creator of this network.” When asked about the

roles he played in the site development, he

responded:

“I saw myself a lot of different ways as an

inventor and as a student activist…I was making

my dreams, my observations and what I talked

about more then just a dream and observation

when I talked about. I took action and I actually

put it, put what I was thinking about into motion

…Well, before I created this website I was

student activist and it’s always been my dream

especially for the future to be a student, a social

activist. And so I saw when I made this

website…it was a way of social activism to get

people to stand up to what they believed in to

talk about it, to discuss it, and to come

together.”

Another manifestation of his visibility within

projects that has helped Maurice to develop a

recognizable identity within the DYN community is

his use of representations of himself in his work. In

his video project entitled Black Pride, one fifth of

the movie is footage of Maurice’s face as he reads a

poem. On his wechange social networking site, he

embedded a promotional video featuring himself in

multiple roles, that of the “nerd” who uses a popular

social networking site and that of the “cool guy”

who uses Maurice’s site. When the radio pod

assignment was to create a movie about an

“American Rebel,” Maurice chose himself and

included his story, his voice, and photos of himself

throughout the video.

“So I started the school recess movement and I

guess that would have made me an American

rebel because I was actually, I was standing

against the laws at my school and I decided that

I wanted to change something.”

2.1.2 Visibility of Project Work

Maurice was also very successful getting his work

viewed by a relatively large audience within the

DYN community; he frequently showcased his work

through formal and informal live performances in

class, pods and online spaces. Online, he utilized

both the DYN remix world site and his own

wechange site. On remix world, he began and/or

contributed to 54 discussions. Some of his posts are

political musings, others are related to cultural

events or styles, and still others are his own written

work, including poems. He posted his Black Pride

video project on his profile page and was a member

of four groups. On wechange, he started seven

discussions and posted two of his own video

projects, Black Pride on his profile page and the

promotional video for the wechange site in the

“about us” section. His online participation in both

Web spaces allowed Maurice to show his work,

receive feedback on it, and comment on and critique

the discussion posts and work of others in the

community. He also cross-referenced his profile and

project visibility, potentially widening the audiences

for his work: On remix world his screen name is the

title of his own social networking site, “wechange”,

and there are links from each site profile page to the

other.

2.1.3 Adult Positioning of Student and Work

A final important factor contributing to the visibility

of Maurice’s project work and the development of

his own identity along with community recognition

of this identity was the frequent positive positioning

of his role and his work by DYN coordinators.

Maurice was sometimes considered “too academic”

or a “know-it-all” by his peers but the DYN

coordinators purposefully worked to change this

perception, encouraging students to see Maurice as

someone who could help them.

“I think the kids see [Maurice] as socially

awkward…I think he’s able to balance that with

some students, but other students are like,

‘Maurice is saying something smart again…’

For me as a mentor when I see those situations

happening it’s like, ‘No, let him speak because

you can learn from him.’”

DYN coordinators helped to validate Maurice’s

role as a media creator by becoming members of his

wechange site. They posted his project work on

remix world, including three interviews Maurice

conducted with adults (a teacher from the school, a

game designer, and a community centre program

leader) as part of the radio pod. They also replied to

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

170

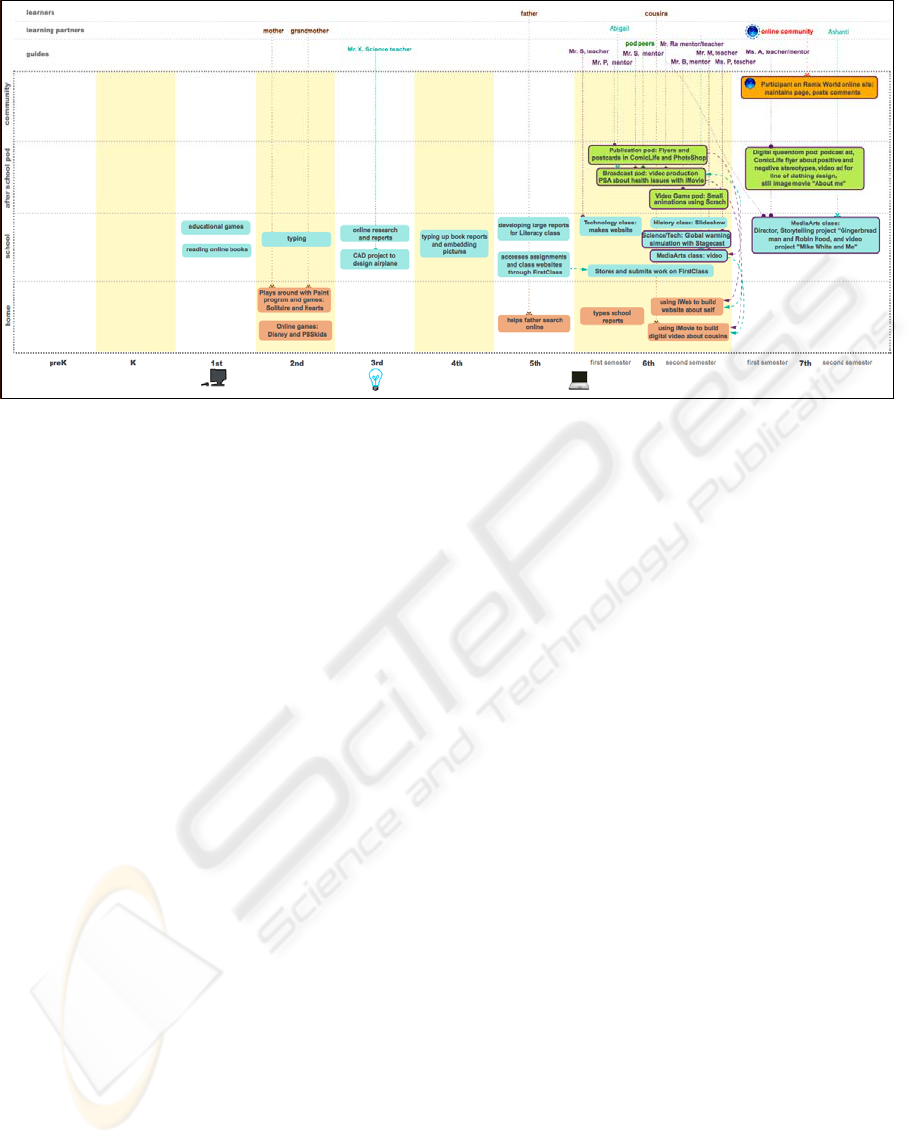

Figure 2: Technobiographical timeline representation for Renee.

his online discussions, commented on his projects,

and provided links to his work. A comment from a

DYN coordinator about one of Maurice’s video

interviews read:

“Very specific and focused questions that

prompted substantive answers from [the

interviewee]! Mistakes we see in a lot of our

interviews are student's asking very short vague

questions, which end up getting short vague

answers unfortunately. You’ve set a good

standard for everyone to keep up between this

and the [game designer interview] piece!”

With the help of DYN coordinators and his own

inclinations toward project production and

presentation, Maurice’s public role as an engaged

expert within the community resulted in new

opportunities for learning. Two DYN coordinators

used Maurice in classes and the after school pods as

an informal assistant both for technical and media

literacy topics. He was also asked to be part of a

student design team to plan elements of a new

building to house their school. These new

opportunities have the potential to strengthen his

own identity as an expert and expand the recognition

of him as an expert to a wider community.

2.2 The Personal Explorer

Renee began middle school without much computer

experience beyond basic word processing but

participated in a range of in school and after school

technology learning opportunities through DYN (see

figure 2). During sixth grade, she participated in the

video pod, the design pod, and the video game pod,

while in seventh grade she participated in the design

pod and the digital queendom pod. In sixth grade,

though Renee had produced and edited a 10-minute

movie about her cousins independently on her own

time, and created a multi-page Web site about her

work, her design interests and talents were not

recognized within the wider DYN community.

Coordinators spoke of her consistent participation

and ability to complete her projects but described

her as “very quiet” and an “average” student. By the

end of her second year in the program Renee’s

identification as a designer evolved and her work

was more visible and widely recognized through her

participation in remix world, the online DYN social

networking site.

2.2.1 Hesitancy to Label Self in Defined

Role

Though Renee created a number of projects across a

range of media including computer games, digital

videos, page layout designs, and Web sites, she was

hesitant to label herself as an expert and often did

not clearly identify her own role in production.

Though her collaborative projects, such as a video

commercial for a line of clothing, sometimes

featured her in an acting role, there are no credits to

identify the roles she played in the development of

the project artefact. When asked about roles she

played in collaborative project work, she was vague

about her particular responsibilities or used “we”

instead of “I” to describe her learning and creating in

DYN programs.

When talking about her knowledge and her own

work she sometimes included a disclaimer. “I’m the

A CULTURE OF SHARING - A Look at Identity Development Through the Creation and Presentation of Digital Media

Projects

171

person for teaching people how to use it…If they

don’t know how to use something, I do – probably.”

Despite having a fully designed profile page on

remix world, with an artistic background image, 28

posts about a range of topics, membership to three

groups, her own video work, and background music,

she warns the interviewer about its incompleteness.

“I actually don’t have that much made, but I

post like discussions and reply to a lot of

things.”

2.2.2 Selective about Shared Work

Renee was not driven to share her technology

project work with a wide audience, and her projects

were often left unpublished. DYN coordinators had

little knowledge of projects she pursued outside of

formal assignments. Though she regularly presented

in classes and pods when it was part of the particular

assignment, she was hesitant to show her work to

outside audiences. One coordinator recounts:

“When I pulled [Renee] for the presentation for

the lady that was coming around and looking

from outside the school, she told me that she

was uncomfortable in talking about what she

was doing. And I kind of joked with her like,

‘You like to do all the work but you don’t want

anyone to see you?’ And she was like, ‘Yeah, I

really don’t want to talk about it all.’”

When Renee chose her own themes, her projects

are often reflections on and explorations of her own

identity, including a still-image movie with voice

over entitled “Princess” about her likes and dislikes.

Her content about herself and her family may have

been less given to wide distribution than projects

with messages specifically designed for the public,

like many of those by Maurice.

“Like well I didn’t post when I did my cousins’

film. I didn’t post it on remix world because I

don’t know, but I just didn’t post it for a lot of

people to see.”

2.2.3 Development of New Roles

Despite her disinclination to present work broadly or

position herself in the community in terms of her

technological project work and skill set, Renee

began to find her own way of participating and

defined new roles in the community for herself.

When she collaborated with a peer who did not

participate in the after school technology pods,

Renee took on the role of “teacher.” Within this

experience, she was able to see herself as someone

with more expert knowledge:

“Well she like found the music, found the

special effects. She edited some of it, but I did

most of it because I knew how to do it

better…Well like I was under – well, I just know

how to do it. So I just taught her. She helped

out. I know somebody has to teach her to learn”

At the end of seventh grade, Renee formed a

design production group with a peer in the design

pod. This labelled and named group was a step

toward branding her work and gaining recognition,

perhaps without having to draw attention to herself

as an individual.

“But this is for design class and we have a

company. So me and my partner, we chose this

because we thought it was unique like a Twilight

Zone has a lot of things that you want to see. So

like we’re going to be making like CD albums,

posters, and stuff light that…Like [Twilight

Zone] is just the name, like people they will

remember us. Okay, they’re unique they do stuff

that’s crazy, good.”

2.2.4 Use of Online Spaces for Presentation

In seventh grade Renee used remix world to show

carefully selected pieces and thoughts within the

community, valuing the feedback for her continued

revisions and production work.

“I like people to see it and critique like how I –

like critique the things like what needs to be

done to it. What can I change?...because it helps

like to make it better. It helps me to make the

best I do better.”

Renee’s discussions, posts, and video work

prompted encouraging responses from the program

coordinators. For her poem post she received

comments from two DYN coordinators, both

complimenting her work and suggesting ideas for

further innovations: “i love your poem. i would like

to see the other ways you can make this look (like a

comic life or short imovie).” One discussion she

began about what to do about violence in schools

prompted three DYN coordinators to reply in ways

that highlighted Renee’s unique position in the

community, including:

“Speaking of trendsetter...How many girls is

making beats like that. You need to slide some of

that over to the spoken word or video for

soundtracks. This year was just a start. Can't

wait to see how you continue to grow your

skills.”

The digital queendom pod coordinator posted a

video by a collaborative group including Renee, an

advertisement for a line of clothing. Given Renee’s

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

172

disinclination to “show off” in person, the online

space may have offered both Renee and the

coordinators a more comfortable way to publicly

showcase her skills and her work.

Though the DYN community may not have

immediately recognized Renee’s entire technology

story, she was growing as a media artist, taking on

roles of producer, videographer, and designer both

with her independent and group work. Renee took

advantage of the opportunities offered through

DYN, and found a way to pursue her own topics and

explore some new roles as a media designer.

3 DISCUSSION

The promise of project development, from concept

to presentation, is clear. From the case learner

stories, we find that artefact production can: (1)

build reputations of students as particular kinds of

participants in the eyes of the community; and (2)

lead to a sense of self as an author, artist, inventor,

creator, or teacher.

These points are impacted by the degree to

which students are participating in the larger

community and sharing their work. Students at

Renaissance Academy who chose not to participate

in the voluntary aspects of DYN were less likely to

evidence identity growth and development as a new

media creator. Though both case students in this

paper developed their skills through formal classes

and pods and followed their own interests to learn

more by playing around with tools and creating their

own interest-driven projects, the degree to which

they shared their new knowledge and were

recognized for their accomplishments differed.

Renee’s initial preference for creating personal

rather than public projects highlights the importance

of attending to engagement in learning across

settings of home, school, and other informal

community spaces (Barron, 2006). Though her

personal projects were less visible to mentors and

peers, they were important learning opportunities

that provided grounding for her later more public

efforts.

Our findings highlight a number of practices

within the DYN environment that impacted

participation, sharing of work, and positive identity

development, including (1) providing multiple

opportunities and spaces for showcasing work, (2)

identifying and labelling clear roles in project

production, (3) encouraging the development of new

roles and practices within the community, and (4)

explicitly positioning student contributions as

valuable.

We believe that the intentional design of learning

environments that attend to identity development

may be productive and more generative than

curriculum alone. The practices identified here may

be informative for those interested in designing such

environments to ensure that despite individual

tendencies or dispositions, all students have

opportunities for participation and growth.

Additionally, although our research effort was

situated in a technology and new media program,

these practices are not intrinsically linked to the

subject itself. Instead, we believe that they can be

adapted for use in many different kinds of project-

based learning environments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been made possible by a grant from

the John D. and Catherine T. Macarthur Foundation.

The authors would like to acknowledge all members

of the research team in Chicago, IL and Stanford,

CA, including Dr. Kimberly Gomez and graduate

students Maryanna Rogers, Jolene Zywica,

Kimberly Richards, Lori Takeuchi, and Daniel

Stringer for their contributions. We also thank the

DYN coordinators, students, and parents who

contributed their time to the case study development.

REFERENCES

Barron, B. (2006). Interest and self-sustained learning as

catalysts of development: A learning ecologies

perspective. Human Development, 49, 193-224.

Emerson, M., Fretz, R. and Shaw, L. (1995). Writing

ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Gee, J. (2008). New times and new literacies: Themes for

a changing world. The International Journal of

Learning, 8.

Henwood, F., Kennedy, H., & Miller, N. (Eds.). (2001).

Cyborg lives? Women’s technobiographies. New

York: Raw Nerve Books.

Hidi, S. & Renninger, K. (2006). The four-phase model of

interest development. Educational psychologist, 41(2).

Jenkins, H., 2007. Convergence culture: Where old and

new media collide. New York: New York University

Press.

Nasir, N. & Saxe, G. (2003). Ethnic and academic

identities: A cultural practice perspective on emerging

tensions and their management in the lives of minority

students. Educational Researcher, 32(5), 14-18.

A CULTURE OF SHARING - A Look at Identity Development Through the Creation and Presentation of Digital Media

Projects

173

Penuel, W. & Wertsch, J. (1995). Vygotsky and identity

formation: A sociocultural approach. Educational

Psychologist, 30, 83-92.

Peppler K., & Kafai Y. (2007). From SuperGoo to

Scratch: Exploring creative digital media production in

informal learning. Media, Learning, and Technology,

32(2), 149-66.

Pinkard, N., Barron, B., Martin, C.K., Gomez, K., &

White, J. (2008). Digital youth network: Fusing school

and after-school contexts to develop youth’s new

media literacies. Paper presented at AERA ’08:

American Educational Research Association Annual

Meeting, New York, NY.

Stodolosky, S. (1988). The subject matters: Classroom

activity in math and social studies. Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

174