CHALLENGES OF SUPERVISING STUDENT PROJECTS

IN COLLABORATION WITH AUTHENTIC CLIENTS

Maritta Pirhonen

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyväskylä

Mattilanniemi 2, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Project-based learning, Project management education, Supervising.

Abstract: There is a growing need for qualified project managers in the field of IS. The competencies and skills

needed in project managers’ work can not be learned only by reading the books. What kind of challenges

does this bring to educators and educational systems, especially in universities? These challenges include

such as, how to teach management and leadership skills and social competence needed in IS project man-

agement? Project-based learning (PBL) is an approach that enables students to learn management and lead-

ership skills successfully in a working life driven project. PBL has proved to be an effective approach for

learning skills and competencies demanded in project working. However, using PBL method alone does not

guarantee learning result. In order to be successful, PBL method requires effective and competent supervi-

sion and guidance of students. This article focuses in supervising work-related project learning carried out

in collaboration with authentic clients.

1 INTRODUCTION

In information systems development (ISD) work is

increasingly organized as projects. Information sys-

tems (IS) projects are complex and difficult to man-

age because a software project can involve software

development, maintenance or an enhancement to

software (Schwalbe, 2004). Given the role of the IS

project manager, interestingly, many argue that

technical skills are not as important as non-technical

abilities in the areas of teamwork and communica-

tions, and self-awareness (Faraj and Sambamurthy,

2006; El-Sabaa, 2001; Brewer, 2005; Gillard, 2005;

Turner and Muller, 2006). Project work requires an

ability to work as apart of a group, to plan the work,

to make decisions as a group, and to communicate.

The leadership skills of the project manager in IS

projects are an important factor contributing to the

success of the projects (Faraj and Sambamurthy,

2006; Bloom, 1996; Turner et al., 2005). Effective

project manager must have good written and oral

communication skills and adequate technical compe-

tence to manage the IS project. Pinto and Kharbanda

(1996) emphasize the increased need for qualified

project managers. Jurison (1999) state that project

managers’ broad experience with managerial and

interpersonal skills is a basis for successful projects.

Therefore, it is very difficult to find an experienced

and available project manager with right qualifica-

tions.

What kind of challenges does the growing need

for the qualified project managers in IS field bring to

the educational systems, especially universities? In

response to challenge is to use project-based learn-

ing approach for learning skills needed in project

work. Focusing on “real work” is a key means of

motivating students to apply competency to an ac-

tion. Pirhonen and Hämäläinen (2005) state that

working life driven projects with close co-operation

and interaction with industrial and business life may

motivate the students to study - not just to take a

degree. Moreover, project work makes it possible for

students to apply theoretical knowledge to practice

(Rebelsky and Flynt, 2000; Byrkett, 1987), which is

important for the development of expertise (Bereiter

and Scardamalia, 1993; Leinhardt et al., 1995; Tyn-

jälä et al., 2003; Tynjälä, 2008a, 2008b). In terms of

expertise, it is also worth mentioning that project

studies may enable students to participate in the

creation of new knowledge rather than confining

themselves to the acquisition of existing knowledge.

However, using PBL method alone does not

guarantee learning result. In order to be successful,

110

Pirhonen M. (2009).

CHALLENGES OF SUPERVISING STUDENT PROJECTS IN COLLABORATION WITH AUTHENTIC CLIENTS.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 110-115

DOI: 10.5220/0001983401100115

Copyright

c

SciTePress

PBL method requires effective and competent su-

pervision and guidance of students.

This paper is organized as follows. First, peda-

gogical background for project-based learning is

reviewed. Then a particular model of this pedagogi-

cal approach based on studies in the field of infor-

mation systems and the model of supervising are

presented.

2 PEDAGOGICAL

BACKGROUND OF

PROJECT-BASED LEARNING

Project-based learning (PBL) refers to a theory and

practice of utilizing real-world work assignments on

time-limited projects to achieve mandated perform-

ance objectives and to facilitate individual and col-

lective learning (Smith and Dods, 1997). A project-

based learning method is a comprehensive approach

to instruction. It is a learning model that involves

students in problem-solving tasks and allows stu-

dents to actively build and manage their own learn-

ing. PBL is linked to a theory of constructive learn-

ing that entails a shift in learning objectives. The

underlying principle is the assumption that learning

occurs during unstructured, complex activities

(Helle et al., 2006).

Developing generic skills such as teamwork is an

inseparable element in many models of project-

based learning: teamwork is an inherent part of a

project. Students involved in projects practice a vast

range of skills in areas of project management,

teamwork, and communications technology – and

also in self assessment. Often collaboration skills are

put into action by the collaborative nature of project

management. In fact, recent studies have suggested

that project work may have many educational and

social benefits (Moses et al., 2000), such as the de-

velopment of communication skills (Pigford, 1992),

along with team-building and interpersonal skills

(Roberts 2000; Ross and Ruhleder, 1993). Working

process of a group is supported by supervisors who

guide and assist students in independent learning and

information retrieval. Teachers supervise the project

process, and monitor the progress and a performance

of students.

Project work in the field of information systems

gives students the possibility to prepare for profes-

sional practice by producing plans, managing sched-

ules, interviewing users and meeting project dead-

lines (e.g. Oliver and Dalbey, 1994. According to

Hakkarainen et al. (2004), the knowledge-creation

perspective is the most dynamic aspect of expertise,

from both the individual and the societal perspec-

tive. For this reason it is important to support

knowledge-creation activities during university stud-

ies (see also Helle et al., 2006).

3 A DESCRIPTION OF THE

PROJECT-BASED COURSE

The main goal of the project course is to provide the

students with opportunities to gain authentic practi-

cal experience of information systems projects (see

Table 1 for a more specific description of what con-

stitutes these skills are and how they are acquired).

Table 1: The learning goals and the implementation of the

project course (Pirhonen & al. 2005, p. 35).

Learning

objective

What? How?

Group

work skills

Goal-oriented and

responsible action,

recognizing stages of

group development,

spirit of the group, the

own role in the group

Allocating the tasks

equitable to the group for

attaining the project

objectives, weakly meet-

ings with the supervisor,

group meetings, discus-

sions, peer reviews

Communi-

cation

skills

Negotiation techniques,

meeting practices,

ability as a public per-

former, speech and

written communication

Group meetings, meetings

with client, supervisors,

and project managers,

steering group meetings,

seminars, presentations,

agendas, memos, minutes,

e-mail

Project

work skills

Project management,

following through the

project

Project plan, phase plans

and reports, weekly plans

and reports, inspection

meetings, steering group

meetings, acting as a

project manager, lectures

given by experts, theme

seminars

Expert in

the techni-

cal content

of project

The knowledge of the

project content

Acquaint oneself with the

project scope, identifying

the training needs, school

oneself, the planned use

of recourses of the client

and the support group

The learning goal is to provide a comprehensive and

realistic view of information systems experts´ work

in both project management and implementation of

the task. Further objectives include familiarizing the

students with the tools and methods of the project

domain, acquisition of project management skills,

leadership and group work skills, communication

skills, and technical competence.

3.1 Learning Environment

The learning environment is maintained in co-

ordination with three parties – the student group, the

university, and the client organization (Figure 1).

CHALLENGES OF SUPERVISING STUDENT PROJECTS IN COLLABORATION WITH AUTHENTIC CLIENTS

111

Figure 1: The actors in the learning environment.

A written cooperation contract between the three

parties is drawn up before the project starts. It covers

the subject matter (a description of the project objec-

tives), the obligations and rights of the contracting

parties, copyrights, guarantees and maintenance,

confidentiality and the concealment of confidential

information, payments and the payment schedule.

The project course is carried out between Sep-

tember and March (26 weeks). The course starts

with lectures and orientation exercises for the stu-

dents. The students form their groups of four to five

members before the task-exhibition session at which

the client representatives present the project assign-

ments. After this session the student groups negoti-

ate the distribution of the project tasks. During the

course each student is expected to use 300 hours for

implementing the project task and 100 hours for

demonstrating project management and project work

skills, including group leading, group work, and

communication. A record of the working hours di-

vided to the tasks is kept. The groups plan their

work, complete the scheduled tasks assigned, and

produce deliverables. Each student is expected to

take the role of project manager and project secre-

tary. These roles rotate every month and therefore

each member of the project group works in both

roles once. In total, a five-student group uses 1,500

hours in planning and implementing the client pro-

ject. The collaboration ends with a steering group

meeting at which the results of the student project

are accepted.

3.2 Project Assignments

The client typically represents a firm such as a soft-

ware house or the IT department of an industrial

organization. The tasks range from extreme coding

projects to developmental projects and research.

They are typically ill-defined and therefore there

may be a need to clarify the task as the project pro-

ceeds. The teachers have responsibility for procure-

ment of project assignments. They contact organiza-

tions and negotiate for possible project subject. In

co-ordination with the potential clients, feasibility of

the overall project concept is developed and as-

sessed. In the beginning of the course the assign-

ments are introduced to the students by the clients.

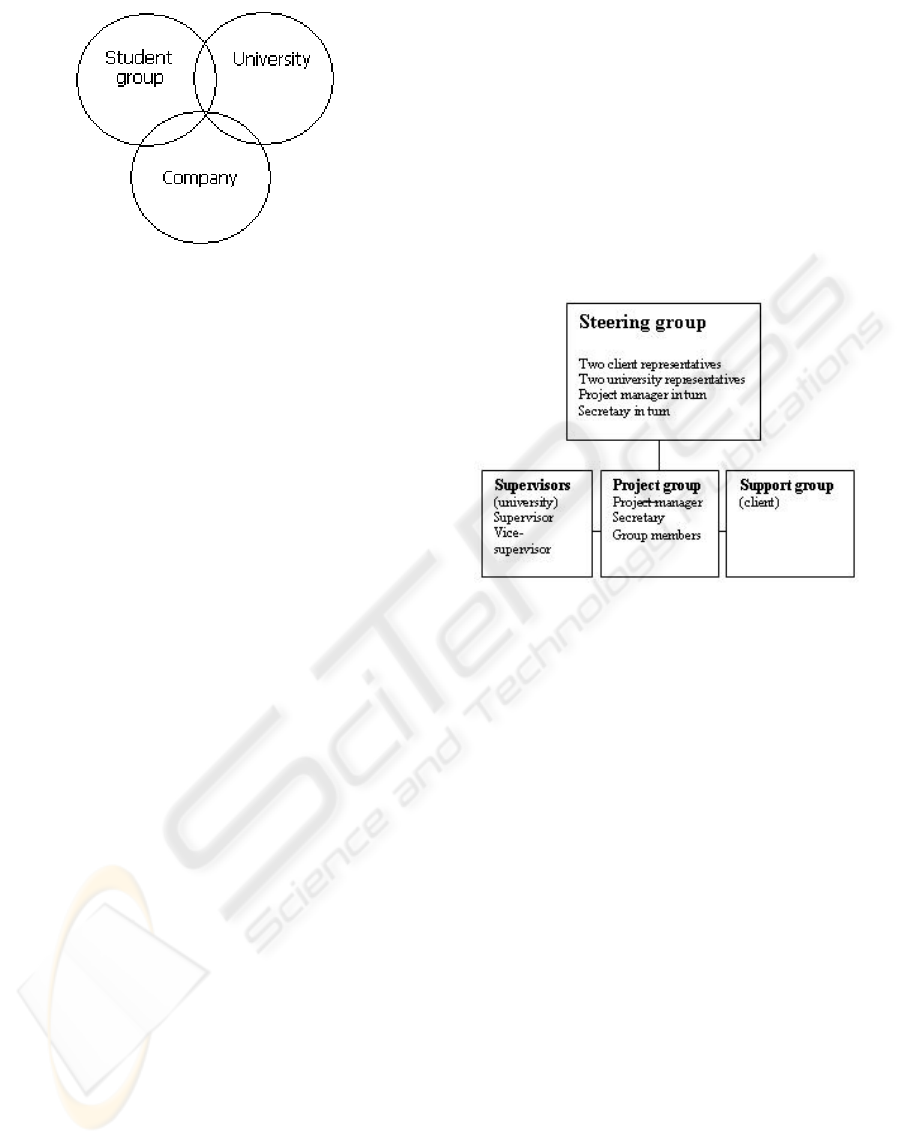

3.3 Project Organization

The project organization comprises a group of be-

tween five students, supervisors, and client represen-

tatives (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The organization of the project.

The steering group is selected during the initial stage

and consists of representatives of the client organiza-

tion, the university (supervisors) and the project

team (the project manager and secretary in turn). It

represents the highest authority in terms of decision-

making, and decides on matters concerning the plans

and issues related to the redefinition of the project

content. One of the client representatives chairs the

group meetings and the project-team manager has

the role of a presenting official. Experts or consult-

ants may also be invited to the steering-group meet-

ings. The support group includes the network set up

by the client, which provides the project group with

content-related professional help when needed.

3.4 Project Group

The project group consists of four to five students.

The role of the project manager and the secretary

rotates every month so that each member of the pro-

ject group takes both roles once. The project man-

ager is responsible for the following:

• coordination and communication with the

client

• maintaining the project plan

• present the proposal to the steering group

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

112

The project secretary is responsible for keeping a

record of meetings and writing memos and minutes.

The project group carries out the project tasks within

the limits of resources available and every student is

responsibly for the quality of his/her work. Students

are expected to review each other’s work to give

feedback.

After the group members have committed them-

selves to the task from those offered by the organiza-

tions of business and industry they get acquainted

with the client organizations by visiting the client

company. They create different forms of communi-

cation channels, such as electronic mail, phone, and

personal contacts. After familiarizing themselves

with the project scope and tasks involved, the project

manager formulates the preliminary project plan in

co-ordination with the group and the client. Since

the project plan is reviewed by the client and the

supervisors the revised project plan is approved by

the steering group. The steering group has a meeting

an average of five times during the project.

3.5 Assessment

The student group is assessed twice during the six-

month period of the project. The first one takes place

in the middle of December after three months work.

The second assessment is carried out at the end of

the project in April. The content of the assessment is

grouped and structured around the themes covering

issues to the course’s objectives and critical to the

effective project management. The course grade for

individual student is calculated on the basis of the

following assessment framework:

• planning (25%)

• communication and co-operation (20%)

• group work (25%)

• attitude (10%)

• outcome (20%)

The assessment process is organized so that both the

teams and the supervisor write up an assessment

report using the assessment framework. The assess-

ment is based on the perceptions of the team work

and documentation of the project process. The as-

sessment of the project outcomes is made by the

client. After the written assessments are delivered,

both supervisors and the team discuss and reflect the

project in order to find out the causes of the success

or the failure of the project. The grading of the

course is mainly based on the debates that emerged

in the discussion about written assessment. If

needed, both supervisors and students have the right

to suggest an individual grade for the student differ-

entiating from the one given to the group. If these

personal grades are given, they are based on a

unanimous decision from all parties participating to

the grading process.

4 SUPERVISING

Effective and competent supervision and guidance

of students is a vital part of a project-based learning

method; PBL method alone does not guarantee

learning result. Especially in the early stages of the

project, the role of the supervisor is vital in support-

ing communication and cooperation with the client.

The experiences of supervisors have shown that the

start-up phase needs to be conducted in a systematic

way if it is to contribute positively to the project

work.

During the project the students are supervised

both by university teachers and by client representa-

tives. The idea is that technical guidance should

come from the client whenever possible, because

they have the knowledge of the specific technologi-

cal requirements. University provides more generic

guidance concerning the project work. Supervisors

have responsibility for the fulfilment of the aca-

demic learning objectives (see Table 1) only, not for

project results to the client or for guiding the techni-

cal content of project. Supervisors guide the students

in finding the essential aspects in order to carry out

the project successfully. Decision-making is left to

the group, although the supervisor may provide a

timeline for the process. The supervisor takes also

part in the meetings with the client. After the meet-

ing the group and the supervisor analyze the meet-

ings together.

Each project group have two supervisors from

the university from which one acts as a vice supervi-

sor. The supervisors are the facilitators and/or

coaches who promote the collaboration and provide

support and guidance. Supervisors also have an im-

portant role in promoting students’ self assessment

on their work. Their obligation is to provide an envi-

ronment for the group where the student can ask

questions when needed and to direct students to use

actively instruction and expert recourses available.

Supervisors support students´ personal growth and

development as well as guide processes of groups.

In order to support the development of reflective

evaluation of the students, the groups are asked to

formulate plans, track progress, construct and test

alternative solutions and evaluate their hypothetical

consequences. Students keep a learning diary in

weekly basis, which contains reflection on their

CHALLENGES OF SUPERVISING STUDENT PROJECTS IN COLLABORATION WITH AUTHENTIC CLIENTS

113

work and learning process. The project manager in

turn writes up the weekly reports and plans as well

as learning diaries. All documents are stored in the

digital learning environment (Optima). This enables

supervisors and group members becoming ac-

quainted with the documents before the guiding

meeting. The meeting between the supervisor and

the group takes place weekly. The main objective of

the meetings is to critically evaluate working and

learning of the students. During the meetings, the

weekly project reports and project plans are dis-

cussed. The project manager and team members

report on the state of the project, which is compared

with the documented expectations in the project

plan. Issues that may possible cause problems during

the project are discussed as well. The project secre-

tary writes memos of meetings, which are also

stored in Optima. Memos are checked in the next

meeting. Between the meetings supervising is ar-

ranged mainly by e-mail.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The challenge of the higher education institutions is

to provide opportunities for students to apply and

develop their knowledge and competencies needed

in the world of work. In the field of Information Sys-

tems it is essential to learn skills of project manage-

ment. Project-based learning approach is process

orientated and the students have responsibilities for

managing the project (timeline, quality, decision

making etc.) and group work.

However, there are some barriers that will pre-

vent educational institutions from applying PBL.

Setting up a market-driven project learning course

may involve some difficulties.

Project based learning method alone does not

guarantee good learning result. Effective and compe-

tent supervision and guidance of students is a vital

part of a project-based learning method. In practise,

it is difficult to find experienced teachers with right

qualifications. This may be caused by resistance

among teaching staff because teachers are not pre-

pared and experienced enough to handle open and

complex learning situations. Good supervisors of the

working life driven projects should have multitude

skills. They need to have understanding of learning

processes alongside a project task. Their task is to

provide an open and convenient learning

environment for the students. Supervisors should

also promote collaboration, provide support and

guidance, and design a grading procedure focusing

on the learning process alongside the evaluation of

the project work. In addition, a challenge from

teachers’ point of view is the procurement of project

assignments. Teachers need to have wide social

network with the representatives in working life in

order to find appropriate project tasks.

Moreover, the learning project designed for

business purposes may cause moral conflicts be-

tween the actors (Vartiainen, 2007). In some cases,

the main objective of the client organisation is to

have a complete system, whereas the most important

goal from the students’ point of view is the acquisi-

tion of knowledge and skills for working life.

After all, learning results from the courses using

PBL are comprehensive and transferrable to the

world of work. However, we need further studies on

how to train and motivate teachers to act as supervi-

sors. Is PBL a solution for this issue?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank the anonymous referees, Eliisa Jau-

hiainen, lecturer Mikko Jäkälä, and Minna Silvenno-

inen their insightful feedback in the development of

this study.

REFERENCES

Bereiter, C., Scardamalia, M., 1993. Surpassing ourselves:

An inquiry into the nature of expertise. Chicago: Open

Court.

Bloom, N.L., 1996. Select the right IS project manager for

success. Personnel Journal. 75(1), 6-9.

Brewer, J.L., 2005. Project managers: can we make them

or just make them better? SIGITE '05: Proceedings of

the 6th conference on information technology educa-

tion, pp. 167-173.

Byrkett, D.L., 1987. Implementing Student Projects in a

Simulation Course. In Thesen, A., Grant, H., Kelton

D., (Eds.) Proceedings of the 1987 Winter Simulation

Conference, pp. 77-81. New York: ACM Press.

El-Sabaa, S., 2001. The Skills and Career Path of an Ef-

fective Project Manager. International Journal of Pro-

ject Management, 19(1), pp. 1-7.

Faraj, S., Sambamurthy, V., 2006. Leadership of Informa-

tion Systems Development Projects. IEEE Transac-

tions on Engineering Management, 53(2), pp. 238-

249.

Gillard, S., 2005. Managing IT Projects: Communication

Pitfalls and Bridges. Journal on Information Science

(31)1, pp. 37-43.

Hakkarainen, K., Palonen, T., Paavola, S., Lehtinen, E.,

2004. Communities of networked expertise:

Professional and educational perspectives. Amster-

dam: Elsevier.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

114

Helle, L., Tynjälä, P., Olkinuora, E., 2006. Project-based

learning in post-secondary education – theory, practice

and rubber sling shots. Higher Education, 51(2), pp.

287–314.

Jurison, J., 1999. Software Project Management: the Man-

ager’s View. Communications of Association for In-

formation Systems, 2, Article 17.

Leinhardt, G., McCarthy Young, K., Merriman J., 1995.

Integrating professional knowledge: The theory of

practice and the practice of theory. Learning and In-

struction, (5)4, pp. 401-408.

Moses, L., Fincher, S., Caristi J., 2000. Teams work (panel

session) in Haller S. (ed.) Proceedings of the thirty-

first SIGCSE technical symposium on Computer sci-

ence education, March 7-12. Austin, USA. New York:

ACM Press, pp. 421-422.

Oliver, S.R., Dalbey, J., 1994. A software development

process laboratory for CS1 and CS2. Proceedings of

the twenty-fifth SIGCSE symposium on Computer sci-

ence education, New York: ACM Press, pp. 169-173.

Pigford, D.V., 1992. The Documentation and Evaluation

of Team-Oriented Database Projects. Proceedings of

the twenty-third technical symposium on Computer

science education, Kansas City, Missouri, United

States. New York: ACM Press, pp. 28-33.

Pinto, J., Kharbanda, O., 1996. How to Fail in Project

Management (Without Really Trying). Business Hori-

zons, 39 (2), p. 45.

Pirhonen, M., Hämäläinen, R., 2005. Oppimispoluille

ohjaamassa: Eväitä oppimisprojektien ohjaajille

(Guiding towards learning: resources for instructors

of learning projects). Jyväskylän ammatti- korkeakou-

lun julkaisuja 50. Jyväskylä. (in Finnish).

Rebelsky, S.A., Flynt, C., 2000. Real-World Program

Design in CS2 The Roles of a Large-Scale, Multi-

Group Class Project, SIGCSE 2000, Austin, TX, USA.

New York: ACM Press, pp. 192-196.

Roberts, E., 2000. Computing education and the informa-

tion technology workforce. SIGCSE Bulletin (32)2, pp.

83-90.

Ross, J., Ruhleder, K. 1993. Preparing IS Professionals for

A Rapidly Changing World: The Challenge for IS

education. In Tanniru, M.R., (ed.) Proceedings of the

1993 Conference on Computer Personnel Research, St

Louis, Missouri, United States. New York: ACM Press,

pp. 379–384.

Schwalbe, K., 2004. Information Technology Project

Management. Boston: Thomson Learning Inc.

Smith, B., Dodds, R., 1997. Developing Managers

Through Project-based Learning. Aldershot/Vermont:

Gover.

Turner, R., Müller, R., 2005. The Project Manager’s

Leadership Style as a Success Factor on Projects: a

Literature Review. Project Management Journal.

36(2), pp. 49-61.

Turner, R., Müller, R., 2006. Choosing Appropriate Pro-

ject Managers: Matching Their Leadership Style to the

Type of Project. Project Management Institute. New-

ton Square; USA.

Tynjälä, P., 2008a. Perspectives into learning at the work-

place. Educational Research Review (3)2, pp. 130-

154.

Tynjälä, P. (2008b) Connectivity and transformation in

work-related learning. Theoretical foundations. In

Stenström, M-L., Tynjälä P., (eds.) Towards integra-

tion of work and learning. Strategies for connectivity

and transformation, Springer, pp. 11-37.

Tynjälä, P., Välimaa, J., Sarja, A., 2003. Pedagogical per-

spectives on the relationships between higher educa-

tion and working life. Higher Education, (46)2, pp.

147-166.

Vartiainen, T., 2007. Moral Conflicts in Teaching Project

Work: A Job Burdened by Role Strains.

Communications of the Association for Information

Systems, (20), pp. 681- 711.

CHALLENGES OF SUPERVISING STUDENT PROJECTS IN COLLABORATION WITH AUTHENTIC CLIENTS

115