DIGITAL MARKETPLACE FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Valentina Ndou, Pasquale Del Vecchio and Laura Schina

eBusiness management section, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy

Keywords: Digital marketplaces, SMEs, Business models.

Abstract: In the networked economy firms are recognizing the power of the Internet as a platform for creating

different forms of relationships and collaborations aimed to enhance value and achieve a sustainable

competitive advantage. Digital Marketplaces represent one of the most powerful solutions adopted by firms

to support the networking practices among firms, especially among SMEs. However in developing countries

the potentialities of digital marketplaces remains largely unexploited. Different human, organizational and

technological factors, issues and problems pertain in these countries, requiring focused studies and

appropriate approaches. This article argues that in order for firms in developing countries to benefit from

digital marketplace platforms it is necessary to root them in an assessment study which permits to

understand the firms preparedness to use the digital marketplace in terms of technological infrastructure,

human resources’ capabilities and skills, integration and innovation level among firms. Based on the

outcomes of this assessment it is then possible to find out a viable digital marketplace model that fits with

actual readiness status of firms and helps them to develop progressively the necessary resources and

capabilities to enhance their competitiveness in the current digital economic landscape.

1 INTRODUCTION

The widespread diffusion of e-Business and rising

global competition have prompted a dramatic

rethinking of the ways in which business is

organized. The new internetworking technologies,

that enhance collaboration and coordination of firms

and foster the development of innovative business

models, are increasingly important factors for firms

competitiveness.

An important trend in various industries is the

creation of Digital Marketplaces as a key enabler

that allows firms to expand the potential benefits

originating from linking electronically with

suppliers, customers, and other business partners.

The number of new digital marketplaces grew

rapidly in 1999 and 2000 (White et al. 2007). In

sectors such as industrial metals, chemicals, energy

supply, food, construction, and automotive, “e-

marketplaces are becoming the new business venues

for buying, selling, and supporting to engage in the

customers, products, and services” (Raisch, 2001).

Over the years digital marketplaces have

produced significant benefits for firms, in terms of

reductions in transaction costs, improved planning

and improved audit of capability, which, if well

communicated, might provide strong incentives for

other organisations to adopt (Howard et al. 2006).

On the other hand, it is widely believed that

digital marketplaces offer increased opportunities for

firms in developing countries by enabling firms to

eliminate geographical barriers and expand globally

to reap profits in new markets that were once out of

reach.

However, it has been observed that although

digital marketplaces are already appearing in almost

every industry and country a very small number of

them have been able to grasp the benefits and resist

on time. In 2006 just 750 active digital marketplaces

were registered on the directory of eMarket Services

compared to 2,233 digital marketplaces identified

by Laseter et al in 2001. the statistics show also that

the use of digital marketplaces in developing

countries is really low. The study conducted by

Humprey et al in 2003 related to the use of b2b

marketplaces in three developing countries shows

that 77 per cent of the respondents had not registered

with a digital marketplace. While of the remaining

23 per cent that had registered with one or more

digital marketplace, only seven had completed at

least one sale. These statistics demonstrate the low

levels of adoption across firms as result of a number

159

Ndou V., Del Vecchio P. and Schina L. (2009).

DIGITAL MARKETPLACE FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 159-166

DOI: 10.5220/0002219601590166

Copyright

c

SciTePress

of barriers faced for the adoption of digital

marketplaces.

Humprey et al (2003) identifies as inhibiting

factors for developing countries the perceived

incompatibility between the use of digital

marketplaces and the formation of trusted

relationships; lack of preparedness, awareness and

the need for training; sophisticated technologies.

Marketplaces’ operators provide standardized

solutions that do neither match the needs of

developing countries nor allow this latter to exploit

new technologies’ potentialities.

In order for developing countries to grasp the

advantages of digital marketplaces it is not feasible

to simply transfer technologies and processes from

advanced economies. … people involved with the

design, implementation and management of IT-

enabled projects and systems in the developing

countries must improve their capacity to address the

specific contextual characteristics of the

organization, sector, country or region within which

their work is located (Avgerou and Walsham 2000).

Therefore, what can and needs to be done in

these contexts is to find out a digital marketplace

model that is rooted in an assessment study which

permits to understand the firms preparedness to use

the digital marketplace in terms of technological

infrastructure, human resources’ capabilities and

skills, integration and innovation level among firms.

Moving away from these assertions, the aim of

this paper is to provide a conceptual framework for

finding out an appropriate digital marketplace

business model for food firms in Tunisian context

that matches with their specific conditions. In

specific we have undertaken a study among food

firms in Tunisia to assess their awareness and actual

preparedness to use the digital marketplace. Based

on the outcomes of that assessment we found out the

appropriate digital marketplace model to start with

as well as an evolutionary path that firms need to

follow in order to enhance their competitiveness.

The remainder of the paper is structured as

follows. The next section discusses the concept of

digital marketplace and their importance for firms.

Next, we present the survey study undertaken with

the objective to understand the e-readiness level

among Tunisian food firms in order to propose a

viable digital marketplace model that is appropriate

to the context under study. We describe the survey

and sample selection. Next we discuss the business

model that fits with actual readiness status of firms

for using new business models. The proposed model

traces an evolutionary path in order for participating

firms to get aware, to learn and adopt to new

business models as well as to develop progressively

the necessary resources and capabilities (relational,

technical and infrastructural) to enhance their

competitiveness in the current digital economic

landscape.

2 DIGITAL MARKETPLACES

Digital Marketplaces are an integral part of

conducting business online (White et al. 2007; Soh

et al. 2002; Gengatharen & Standing 2005; Markus

& Christiaanse 2003; Kambil & van Heck 2002;

Koch 2002). Simply speaking, this application can

be defined as web-based systems that link multiple

businesses together for the purposes of trading or

collaboration (Howard et al., 2006).

Digital marketplaces are based on the notion of

electronically connecting many buyers and suppliers

to a central marketspace in order to facilitate

exchanges of, for example, information, goods and

services (Bakos, 1991; Bakos, 1998; Grieger, 2003;

Kaplan & Sawhney, 2000).

Digital Marketplaces have become increasingly

used across industries and sectors, nowadays, there

exits different types and categories of these

technological platforms. Some authors categorize

them based on the functionalities they offer (Dai and

Kauffman, 2002; Grieger, 2004; Rudberg et al.,

2002) some based on number of owners and their

role in the marketplace (Le 2005).

Three classes of marketplace ownership are

commonly identified:

Third party or public marketplaces are owned

and operated by one or more independent third

parties.

Consortium marketplaces are formed by a

collaboration of firms that also participate in the

marketplace either as buyers or suppliers

(Devine et al., 2001).

Private marketplace is an electronic network

formed by a single company to trade with its

customers, its suppliers or both (Hoffman et al.,

2002).

Consortium marketplaces were identified as most

likely to be sustainable (Devine et al., 2001), as the

founders can introduce their own customers and

suppliers to the marketplace, helping the

marketplace establish a viable level of transactions –

a ready source of buyers and suppliers not available

to third party marketplaces (White et al., 2007).

According to Kaplan and Sawhney (2000) the

digital marketplaces add value through two basic

functions: aggregation and matching.

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

160

The aggregation mechanism involves bringing

many buyers and sellers together under one roof,

which facilitates “one-stop shopping” and thus

reduces transaction costs.

The matching mechanism brings buyers and

sellers together to dynamically negotiate prices on a

real-time basis.

Howard et al.’s (2006) argues that there are

significant evidences regarding the benefits that

firms could realize by using digital marketplaces in

term of reductions in transaction costs, improved

supplier communication, improved planning and

improved audit of capability. While Rask and Kragh,

(2004), classify the main benefits for participation in

a digital marketplace into three main categories:

• efficiency benefits (reducing process time

and cost);

• positioning benefits (improving company’s

competitive position);

• and legitimacy benefits (maintaining

relationship with trading partners).

However, most of the implemented digital

marketplaces have failed to realize their core

objectives and to deliver real value for their

participants. According to Bruun, Jensen, &

Skovgaard (2002), many digital marketplaces have

failed as they have been founded on optimism and

hope rather than on attractive value propositions and

solid strategies.

Evidently, the benefits that could be created via

digital marketplaces has generated tremendous

interest. This has led to a large number of e-

marketplace initiatives rushed online without

sufficient knowledge of their customers’ priorities,

with no distinctive offerings, and without a clear

idea about how to become profitable (Wise &

Morrison, 2000). Digital marketplaces’ operators

provide standardized solutions that do neither match

the needs of firms nor allow this latter to exploit new

technologies’ potentialities. Also they ignore the fact

that most industries are dominated by small and

medium enterprises that are far less likely to use new

technologies as result of resource poverty, limited IT

infrastructure, limited knowledge and expertise with

information systems.

Finally, White et al. (2007) claim that developing

and creating high-value-added services is

challenging for digital marketplaces as technology is

not in place to enable more sophisticated forms of

real-time collaboration among multiple participants.

Therefore, offering simply a standard

marketplace platform will result in a failure of the

initiative as firms might not be prepared to use it, do

not see the value proposition and hence they remain

disinterested in using the platform for integration.

According to Rayport and Jaworski (2002), the

process of convincing organizations to join the

digital marketplace is both long and expensive,

despite the fact that the same offers its participants

appropriate economic incentives. On the other hand,

prospective buyers and suppliers will not join the

digital marketplace only on “visionary predictions of

the glorious future of B2B e-trade; they must see the

benefits in it right now,” according to Lennstrand et

al. (2001). Therefore, finding a business model that

provides enough value to trading partners, to justify

the effort and cost of participation is a substantial

challenge associated with the creation of a digital

marketplace (Rayport & Jaworski, 2002).

3 METHODOLOGY

In order to capture the state of the preparedness of

firms to adopt a new internetworking platform a

survey has been conducted to collect data. The

sample of the study consisted on Tunisian food

SMEs chosen according to the EU definition of

firms with 10-250 employees.

The population of firms was derived from a

database of the Tunisian industry portal containing

data on Tunisian food processing firms.

The sample is made of 27 firms with 13 medium

size enterprises and 14 small size enterprises. Out of

the 27 firms surveyed, 18 questionnaires were

useful for the survey producing a response rate of 67

%.

The data were collected in march 2008, over a

period of three weeks, by means of face to face

interviews and in some cases e- mail surveys (when

mangers didn’t gave use the availability to realize a

face – to face interview). We used the questionnaire

as a tool to gather data. The final questionnaire

included a 3 pages structured questionnaire with a

set of indicators organized into the following

modules:

- The technological networks in which are

included indicators that measure the ICT

infrastructure for networking in the firms in

particular the use of Internet, the use of Local Area

Networks (LAN) and Virtual Private Network

(VPN) for remote access.

- The e-business activities that firms use to

support and optimize internal business processes,

procurement and supply chain integration, marketing

and sales activities, use of e-business software;

DIGITAL MARKETPLACE FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

161

- The level of awareness and use of digital

marketplaces aimed to identify if firms use digital

marketplace and/or are aware about the potentialities

and benefits they can deliver.

- Limitations and Conditions to e-Business –

aimed to identify the perceived factors and barriers

that firms consider as limitation for the adoption and

use of e-business models.

Data provided have been analysed by using a

series of descriptive statistics processed into the

Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS version

12.0 for Windows.

4 SURVEY RESULTS

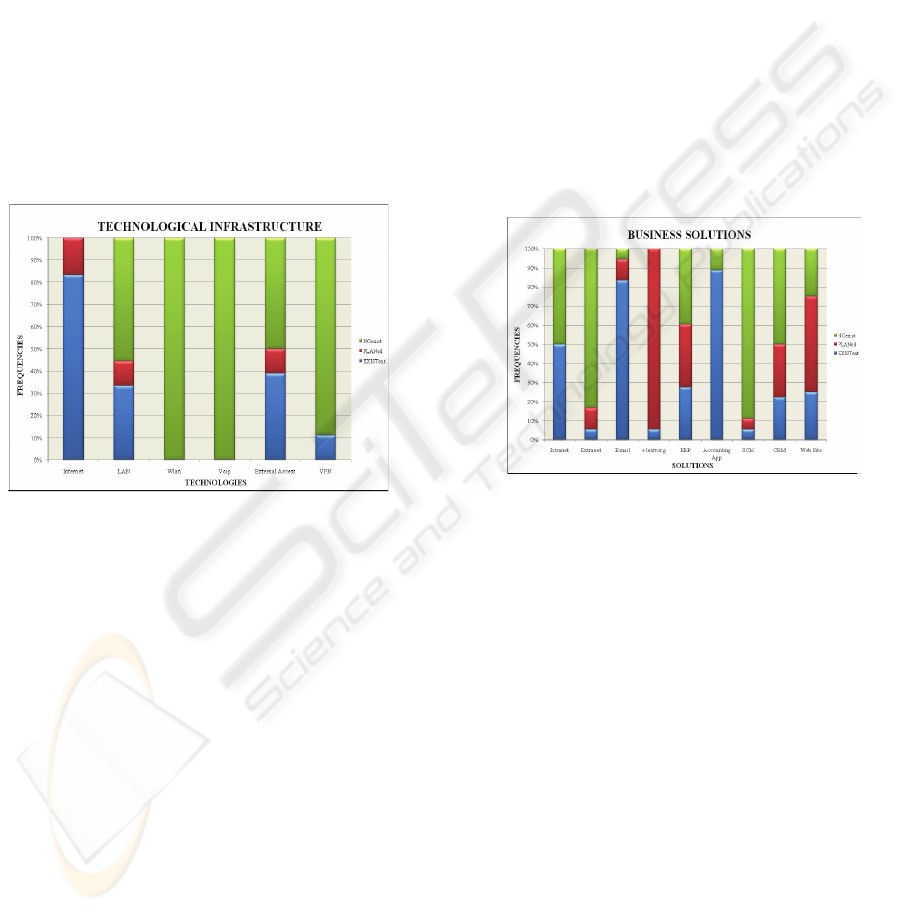

The results of the survey regarding the ICT

networking are displayed in the figure 1.

Figure1: Technological Infrastructure.

The results show a shortage of networking

technological infrastructure. Generally, the surveyed

firms have internet connection or plan to have it, but

when it comes to technologies used to connect

computers such as LAN, WLAN, VPN the firms

surveyed reported to use them in a very low rate.

LAN is existent in 33 % of firms surveyed, while

just 11% of the firms have the VPN since it is

inherent to the technology infrastructure of medium

sized firm. The VOIP is inexistent in all firms and is

not even planned to be used. The results also,

confirmed the limited awareness of firms for ICT

issues and a general lack of ICT skills within the

industry. In fact, although firms surveyed do have an

Internet connection or are planning to have one they

don’t have vision about its usage. Only 39% of the

firms allow its employees to have an external access

and 11% are planning to have it whereas the 50%

remaining don’t even plan for it.

E-business activity - The results regarding the

business solutions used by Tunisian Agrifood firms

are displayed in the figure 2. According to the

results, Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems

are the most diffused among Agrifood Industry.

Also, there is a wide range of firms that are planning

to implement the ERP. The firms that neither have

ERP nor plan for it argue on the fact that the size of

their firm is manageable without any IS that require

tremendous efforts and investments. This is

consistent with the fact that accounting application

(excel, software, in house solutions) are widely

diffused.

Even though some firms do have the Intranet as a

mean of intra organizational communication, its

level of use remains relatively low and its

functionalities under used. Although, Intranet exist

yet the purpose of use and its outcome is relatively

low.

Figure 2: e - Business Solutions.

Only one of the medium sized enterprises use or

plan to use the Extranet whereas the small firms

have no plan for adopting the extranet as a business

solution that will connect them to their trading

partners. The elearning application is not highly

diffused. However, the firms consider it very

important and the results show that all our sample

plan to have it. This is consistent with the

government politic as it is providing incentives and

support for elearning adoption.

The findings concerning the level of diffusion of

extranet are consisting with the findings concerning

the Supply Chain Management (SCM). The

managers of SMEs in agrifood sectors believe that

the SCM overpasses their needs and it is an extra

expense. Therefore, we find out a high rate of firms

that don’t even plan to implement SCM.

The level of diffusion of web sites remains

relatively low and the firms do not get the point with

such an investment and its benefits. In fact, a lot of

managers-especially in small size companies-believe

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

162

that a web site’s requirements in term of investment

are higher than the expected returns and benefits.

Our findings are consistent with the e-

BusinessW@tch (2006). In fact, according to e-

Business W@tch ERP is largely adopted among

agrifood firms since it allows process integration and

synergies.

E-Marketplace Awareness – Some questions

regarding the level of knowledge, the willingness

and the likelihood of adoption of a trading platform

as a business solution were inserted in the study, as

well. The survey data reported that 27.8% of the

firms were aware of the digital marketplace and able

to provide a brief description of it. Among the firms

aware of digital marketplace only one firm is a small

size one. In contrast, 72.3% of the firms plan to

undertake e-business activities without any intent to

integrate their system with their main trading

partners.

Limitations and Conditions to E-Business - The

questionnaire was also aimed to identify the main

obstacles and limitations that companies encounter

in performing online transactions and e-business

activities. In particular we asked them to identify the

most important constraints they face in an attempt to

use different ebusiness platforms or models. Nine

main indicators resulted as most influential:

Lack of human capital (HC); Fear of loosing

privacy and confidentiality of the company’s

information (PCI); Lack of financial resources,(FR);

Lack of top management support, (TMS); Strict

government regulation, (SGR); Lack of regulations

for online payment (ROP); Our partners do not use

e-business (PU); Benefits of using e-business are not

clear, (BEB); IT and software integration problems

(ITSI). The results are displayed in Figure 3.

In general terms, the results show that the lack of

regulations for online payment is the main inhibitor

of e-business followed by the fact that business

partners using e-business and the lack of resources

especially human capital. In fact, past studies on e-

business highlighted some challenges that

Figure 3: Factors inhibiting eBusiness adoption.

e-business adopters might face. Notice that training

and finding qualified e business employees are

among the most critical challenges that e-business

adopters might face.

However, even though we notice some degree of

e-business awareness, the volume of transactions via

Internet is still of an issue. There are no transactions

on line since SMEs are not linked to an agency that

secures electronic certification. Further, the

problems of payment security still persist along with

logistic and quality problems. Therefore, the only

symptoms of EC in Tunisia are e-mail, e-catalog and

information portals and at some exceptions the

possibility to order online. The rest of the transaction

is done via classical way. Thus, we cannot really talk

about EC in Tunisian SMEs as it still needs time to

emerge.

5 THE DIGITAL MARKETPLACE

BUSINESS MODEL

The research findings show that Tunisian food firms

didn’t get the full use of e-business nor get tangible

benefits. The managers proved a good level of

theoretical knowledge concerning e-business and its

benefits however practical cases didn’t bubble up

yet. This is due to managerial and technical

inhibitors that our prospects expressed.

Such results suggest avoiding the choice of

solutions which tend to use sophisticated

technologies, require high level of integration and

collaboration among supply chain actors or that

point directly to the integration firms. Rather, it is

reasonable opting for ‘lighter’ solutions, to start

involving a limited number of operators, particularly

aware and interested, but not necessarily equipped,

around a simple solution that requires lower levels

of innovation and coordination capabilities by local

firms. It is important to note that the design of a

marketplace is not a given, it highly depends on

users ability to recognize opportunities, benefits as

well as the barriers to be faced by them. However, in

most cases a kind of intermediary actor is needed

which bring buyers and sellers together and tries to

create awareness among them by providing the

platform

The intermediary actor arrange and direct the

activities and process of the digital marketplace. The

role of intermediaries can be played by a

confederation of the industry, industry associations

or other types of representative organizations that

are able to secure a critical mass of users to the

DIGITAL MARKETPLACE FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

163

digital marketplace.

This marketplace model is known in literature as

Consortium marketplace. Different authors have

identified it as most likely to be sustainable

especially for fragmented industries and SME

(Devine et al., 2001), as the founders can introduce

their own customers and suppliers to the

marketplace, helping the marketplace establish a

viable level of transactions.

In contrast to a private marketplace, a consortium

marketplace by definition is open to a number of

buyers and suppliers in the industry, if not all,

increasing the likelihood of participation and use.

Thus, in this initial stage the digital marketplace

will serve as aggregator of buyers and sellers in a

one single market in order to enhance products

promotion and commercialization. It is aimed at

offering a one-stop procurement solution to firms by

matching buyers and sellers through its website.

The digital marketplace in this case will serve as

a context to initiate a change management process

aimed at creating, overtime, the necessary

technological and organizational prerequisites for

any further intervention aimed at developing and

enhancing the competitiveness of firms. Simple

trading services such as e-Catalogue, e-mail

Communication, Request for Quote, Auction are

suitable for firms in this stage. These services do not

support new processes, they just replicate the

traditional processes over the Internet, in an effort to

cut costs and accelerate the process (POPOVIC,

2002) .

However, this is just the first step of an

evolutionary learning process of creation,

development, consolidation and renewal of firms

competitiveness through e-Business.

This stage is a prerequisite for increasing the

firms awareness regarding the potentialities and the

benefits of e-Business solutions. Any solution, no

matter how simple, will not be automatically

adopted if not framed in a wider awareness initiative

aimed at informing the relevant stakeholders of the

impacts and benefits that this solution can have for

them over the short and the medium-long term. To

further increase the awareness of SME and for

building the local SMEs capabilities some training

programs that tap on ICTs could be of great support

for firms.

Starting to use the basic services offered by

digital marketplaces in this initial stage is an

indispensable phase for creating the right conditions

for pursuing an evolutionary pathway towards more

collaborative configurations. For example the use of

eCatalogues or Auction services involves

information sharing or data exchange between

trading parts. Through communication with trading

partners firms starts to pull inside the marketplace

other supply chain firms with which they realize

trade.

In this way firms start to move towards more

collaborative settings where suppliers, customers,

and partners share more information and data

between them, create strong ties as well as longer-

term supplier-customer relationships.

Then, to support this new type of relationships

created among participating and to provide more

value added for them the digital marketplace needs

to evolve towards the development of new services

that reinforce the relationships among different

actors, create new ones and exploit partnerships in

order to enhance services. More advanced

collaborative technologies could be implemented in

order to connect, suppliers, customers and partners

in a global supply network where critical knowledge

and information about demand, supply,

manufacturing and other departments and processes

is shared instantaneously. More value added services

could be provided at this stage such as – online

orders, transactions, bid aggregation, contract

management, transaction tracking, logistics,

traceability etc - which permits the supply chain

actors to integrate their operations and processes.

The use of such services as bid aggregation,

logistics, traceability etc doesn’t simply enable firms

to exchange knowledge and information and but also

to develop it together in order to better understand

customers and market trends.

Thus a further stage of digital marketplace could

be developed to leverage on the integrated and

collaborative culture of the firms to create

distributed knowledge networks, composed by a set

of dynamic linkages among diverse members who

are engaged in deliberate and strategic exchanges of

information, knowledge and services to design and

produce both integrated and/or modular products.

Networking services could be implemented in this

stage such as Virtual Project Workspace (VPW) for

product development teams, elearning services,

knowledge management, virtual communities.

The approach proposed suggest that firms need

to go through a sequential stages where the activities

are cumulative. This means that firms in stage 2, for

example, undertakes the same activities as those in

stage 1, that is communicating with customers and

suppliers via email and using the web for realizing

catalogues, but in addition they start collaborating

and transacting online with other actors of the

supply chain.

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

164

6 CONCLUSIONS

The thesis underpinning this paper is that the context

features shapes the type of the business models for

digital marketplaces. It is argued that before starting

a digital marketplace initiative it is necessary to

undertake a context assessment that permits to

understand the firms preparedness to use the digital

marketplace in terms of technological infrastructure,

human resources’ capabilities and skills, integration

and innovation level among firms.

On this basis a specific evolutionary approach

has been presented. The aim is to provide

developing firms with solutions that match their

needs and that help them to get aware, to learn and

adopt to new business models as well as to develop

progressively the necessary resources and

capabilities (relational, technical and infrastructural)

to enhance their competitiveness in the current

digital economic landscape.

Our approach also presents important

implications. The concept of digital marketplaces is

useful for firms in developing countries, however

despite the promise they remain largely unused

because of the inadequacy of solutions to context

features. We argue that the success of a digital

marketplace initiative needs to be rooted in an

assessment study of the context that permits to

understand the firms preparedness to use the digital

marketplace in terms of technological infrastructure,

human resources’ capabilities and skills, integration

and innovation level among firms.

Based on the outcomes of this assessment it is

then possible to find out a suitable business model

for the digital marketplace that show sensitivity to

local realities and ensure the effective participation

of the firms.

It is essential to start with feasible initiatives and

build up steadily the qualifications necessary for

facing hindrances. However, starting at the right

point and in the right way doesn’t automatically

guarantee success and competitive advantage to

destinations, but can represent a way to start

admitting the fundamental role of the innovation,

according to the need to survive in a high complex

environment.

In today’s business environment firms and

destinations need to continuously upgrade and

develop organizational structures, assets and

capabilities, the social and customer capital to

enhance to enhance their competitiveness. Thus

firms need to adopt a co-evolutionary that stimulate

collaboration and coordination among firms. The

active role of an intermediary is crucial especially at

the earliest stages, to raise awareness, assure firms

participation, build and maintain wide commitment

and involvement.

The ideas that we propose need to be refined in

further conceptual and empirical research. First, a

field analysis is needed in order to appraise and to

validate the evolutionary path proposed in this

paper. Second, it will be important also to monitor

the process of adoption of digital marketplace and

their specific impacts on firms competitiveness.

Third, further research could also focus o how to

realize digital marketplace solutions that integrates

internal business systems with a common platform.

The research can be oriented toward identification of

a unifying solution for SME, in which there is a

convergence and integration of activities, considered

as part of a joint entity. This solution may be able to

generate a high number of benefits, related to the

opportunity to decrease errors and mistakes in the

transactions, to reduce the duplication of activities,

to manage business in a simple and fast way.

Further research could be also focused on

understanding the factors that inhibit or support the

passage of firms from one stage to another of the

evolutionary model.

REFERENCES

Andrew, J. P., A. Blackburn H. L. Sirkin 2000. The B2B

opportunity: Creating advantage through e-

marketplaces. Boston, MA: The Boston Consulting

Group.

Avgerou, C., & Walsham, G. (Eds.). 2000. Information

technology in context: Implementing systems in the

developing world. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate;

Bakos, J. Y. 1991. A strategic analysis of electronic

marketplaces. MIS Quarterly, vol. 15, no 3, pp. 295-

310.

Bakos, J. Y. 1997. Reducing buyer search costs:

implications for electronic marketplaces. Management

Science, vol. 43, no 12, pp 1676-1692

Bakos, J.Y. 1998. The emerging role of electronic

marketplaces on the Internet. Common ACM, vol. 41,

no. 8, pp. 35–42.

Bruun, P., Jensen, M., & Skovgaard, J. 2002. e-

Marketplaces: Crafting A Winning Strategy. European

Management Journal, vol 20, no 3, pp 286-298.

Dai, Q., & Kauffman, R. J. 2002. Business Models for

Internet-Based B2B Electronic Markets. International

Journal of Electronic Commerce, vol. 6, no 4, pp. 41-

72.

Devine, D.A., Dugan, C.B., Semaca, N.D. and Speicher,

K.J., 2001. Building enduring consortia. McKinsey

Quarterly Special Edition, no 2, pp. 26-33.

e-Business W@tch 2006. The european ebusiness report:

a portrait of ebusiness in10 sectors of the economy.

DIGITAL MARKETPLACE FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

165

European Commission's Directorate General for

Enterprise and Industry

Grieger, M. 2003. Electronic marketplaces: A literature

review and a call for supply chain management

research. European Journal of Operational Research,

vol. 144, pp 280-294.

Grieger, M. 2004. An empirical study of business

processes across Internet-based electronic

marketplaces. Business Process Management Journal ,

vol. 10, no 1, pp. 80-100.

Hoffman, W., Keedy J. and Roberts, K. 2002. The

unexpected return of B2B. McKinsey Quarterly, vol.

3, pp. 97-105.

Howard, M., Vidgen, R. and Powell, P. 2006. Automotive

e-hubs: exploring motivations and barriers to

collaboration and interaction. Journal of Strategic

Information Systems, vol. 15, no 1, pp 51-75.

Humphrey, J., Mansell, R., Paré, D., & Schmitz, H. 2003.

The reality of E-commerce with developing countries.

A report prepared for the Department for International

Development’s Globalisation & Poverty Programme

jointly by the London School of Economics and the

Institute of Development Studies, Sussex,

London/Falmer, March.

Kambil, A., and van Heck, E. 2002. Making markets. How

firms can design and profit from online auctions and

exchanges. Harvard Business School Press, Boston,.

Kaplan, S. and Sawhney, M., 2000. E-hubs: the new B2B

marketplaces. Harvard Business Review, vol. 3, pp.

97-103.

Koch, H. 2002. Business-to-business electronic commerce

marketplaces: the alliance process. Journal of

Electronic Commerce Research, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 67-

76.

Laseter, T., Long, B. and Capers, C., 2001. B2B

benchmark: the state of electronic exchanges. Booz

Allen Hamilton.

Le, T. 2005. Business-to-business electronic marketplaces:

evolving business models and competitive landscapes.

International Journal of Services Technology and

Management, vol. 6, no 1, pp. 40-53.

Lennstrand, B., Frey, M., and Johansen, M. 2001.

Analyzing B2B eMarkets, ITS Asia-Indian Ocean

Regional Conference in Perth, Western Australia, July

2-3, 2001.

Markus, M.L. and Christiaanse, E. 2003. Adoption and

impact of collaboration electronic marketplaces,

Information Systems and E-Business Management,

Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 139-155.

Popovic, M. (2002). B2B e-Marketplaces, from

http://europa/eu.int/information_society/topics/ebusine

ss/ecommerce/3information/keyissues/documents/doc/

B2Bemarketplaces.doc

Raisch, W. D. 2001. The e-Marketplace: Strategies for

Success in B2B eCommerce. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rask, M. & Kragh, H. 2004. Motives for e-marketplace

participation: Differences and similarities between

buyers and suppliers. Electronic Markets, vol.14, no.

4, pp. 270-283.

Rayport, J. F., and Jaworski, B. J. 2002. Introduction to e-

Commerce. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp.204–206.

Rudberg, M., Klingenberg, N. and Kronhamn.K., 2002.

Collaborative supply chain planning using electronic

marketplaces.

Integrated Manufacturing Systems, vol.

13, no 8, pp. 596-610.

Soh, C. and Markus, L.M. 2002. B2B E-Marketplaces-

Interconnection Effects, Strategic Positioning, and

Perfor-mance. Systemes d'Information et

Management, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 77-103.

White, A., Daniel, E., Ward, J., and Wilson, H. 2007. The

adoption of consortium B2B e- marketplaces: An

exploratory study. Journal of Strategic Information

Systems, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 71-103.

Wise, R., & Morrison, D. 2000. Beyond the Exchange -

The Future of B2B. Harvard Business Review,

November-December, pp. 86-96.

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

166