ICT USE IN SMES

A Comparison between the North West of England and the Province of Genoa

R. Dyerson, G. Harindranath, D. Barnes

Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX, U.K.

R. Spinelli

DITEA – Facoltà di Economia, Università degli Studi di Genova, Via Vivaldi 5, I-16126 Genova, Italy

Keywords: Information and communications technology (ICT), Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), Adoption,

e-Commerce.

Abstract: This paper explores patterns of adoption and use of information and communications technology (ICT) by

small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in both the North West region of England and the Genoa region

of Italy. Here we present the results of this two region survey drawn from two economically significant

sectors: high technology manufacturing and food processing. Our main objectives were to explore and

compare ICT adoption and use patterns by SMEs in the two regions to identify factors enabling or inhibiting

the successful adoption and use of ICT, and to explore the impact of ecommerce on the SMEs. While our

main result indicates a generally favourable attitude to ICT amongst the SMEs surveyed, it also suggests a

number of differences between the two regions. English SMEs report greater uses of sophisticated ICT

applications but Italian SMEs make more use of basic ICT functionality. English SMEs also report more

focus on operational matters and often ignore strategic considerations, unlike their Italian counterparts.

Having said that, the English SMEs pay less attention to applying ecommerce but appear to make more

effective use of the Internet than the Italian SMEs.

1 INTRODUCTION

The most recent report available from e-Business

watch (2008) makes the point that small and

medium sized enterprises (SMEs) are not deploying

information and communications technology (ICT)

in the same manner as their larger sized cousins.

That is, SMEs view ICT as a way of cutting costs

and boosting productivity but are largely ignoring

the potential of ICT to enhance strategic

opportunities (Ordanini, 2006; Maguire et al., 2007)

such as market expansion. This is important not only

because SMEs form a significant part of the

European business community contributing to value

added, employment and tax revenues but also since

globalisation is affecting SMEs.

In this paper we present an exploratory survey of

two areas; the province of Genoa in Italy and the

North West region of England. We focus on two

contrasting sectors important to both regions, high

technology manufacturing and food processing and

focus our attention on SMEs; defined as a firm with

250 or less employees. Our intention through the

survey is to probe the factors important in relation to

the use and application of ICT and to compare

possible differences in approach between the two

regions. Thus, we examine how SMEs in the two

regions use ICT and explore whether a common

attitude to ICT exists across both countries.

2 REGIONAL PROFILES:

ESTABLISHING CONTEXT

In this section we briefly explore the regional profile

of the North West of England and the province of

Genoa. We find that the two regions share many

broad characteristics with both areas undergoing a

process of renewal having once been dependent on

the wealth brought in from former great trading

ports.

244

Dyerson R., Harindranath G., Barnes D. and Spinelli R. (2009).

ICT USE IN SMES - A Comparison between the North West of England and the Province of Genoa.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 244-251

DOI: 10.5220/0002233502440251

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2.1 The North West of England

The North West of England comprises of five local

authority districts and includes two major UK cities,

Manchester and Liverpool. The decline of the

traditional heavy industries has brought with it the

challenge of industrial regeneration and witnessed a

shift towards the service sector. Nonetheless, the

North West remains the single biggest contributor to

UK manufacturing, some 13% of total turnover in

2005 (ONS, 2008). When gross value added is

calculated on a per head basis, the region is ranked

seventh out of nine. The region has a collective

population of 6.8 million people, of which 2.97

million are employed in 186000 firms (ONS, 2008)

covering an economically diverse range of industries

(NRDA, 2006). Some 99.5% of firms in the North

West have less than 250 employees. (ONS, 2007).

2.2 Genoa

With a different economic structure and dynamic

from the Milan and Turin, Genoa has always stood

out as the weak ugly duckling of the so-called Italian

“industrial triangle” (Caselli, 2003). The gross per

head value added generated in the province is €

23067, ahead of the Italian average (€ 21806) but

below Turin (€24564) and Milan (€ 33605) (ISTAT,

2008a), placing Genoa 38th out of 103 Italian

provinces. Average firm size is very small – as

everywhere in Italy – and only 0.1% of firms have

more than 250 employees (Benevolo et al., 2008).

With the retreat of the State from the economy and

the closure of most public-owned heavy industry,

Genoa has been undergoing a process of industrial

reorganisation. Indeed, manufacturing accounts for

no more than 8.8% in terms of firms and 16.8% in

terms of employees. From a total population of

around 880000 people, 285000 are employed in

67000 firms; as regards manufacture, 5900 firms

employ more than 48000 people (ISTAT, 2008b).

3 ICT AND SMES IN ENGLAND

AND ITALY: A BRIEF REVIEW

Here we briefly review the more recent literature as

it relates to SMEs use of ICT in the UK and Italy,

ignoring more general studies of ICT adoption by

SMEs for space reasons.

A feature of ICT research within SMEs in both a

British and Italian context is the essentially

uniformity of findings. For instance, most studies

find that SMEs use ICT in a reactionary manner in

response to customer needs and that they are rarely

strategically oriented (see Hicks et al.’s, 2006;

Cioppi, et al., 2003; Maguire et al., 2007 for recent

examples). Additionally, Harindranath et al.’s

(2008) found that in sectors such as food and

transport SMEs were also being influenced by

compliance requirements to adopt certain types of

ICT. Exceptionally, Drew (2003) found that some

firms in high-technology sectors linked their use of

ICT to business strategies. This may reflect the

unique characteristics of high–technology sectors,

although, Ordanini (2006) found a growing

awareness of the strategic role of ICT by Italian

SMEs owner/managers.

Several studies have questioned the validity of

various stage adoption models to the SME (Martin et

al., 2001; Levy et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2004),

characterising SME owner-managers as essentially

cautious. Cioppi et al.’s (2006) results showed a

high level of heterogeneity in ICT adoption paths,

with some Italian SMEs using a naïve approach

while others followed a more structured approach to

ICT investments. This may be influenced by the

owner manager not having a sufficiently technical

background to be able to understand the potential of

ICT (Gramignoli et al., 1999; Pavic et al., 2007).

Balocco et al. (2006) found that top-management

commitment, the presence of a pivotal figure (not

necessarily the owner or CEO), and the work of a

competent and effective IT department were all

important determinants of ICT adoption by Italian

SMEs.

That cautious nature is also reflected in Owens et

al. (2001) survey of SMEs adoption of ecommerce.

They found the Internet being used for

communication and “window shop” marketing

rather than for on line ordering. Marasini et al.’s

(2008) recent study of ecommerce adoption also

concluded that SMEs were apt to improvise rather

than plan such adoption. There is some, albeit

limited, evidence that planning does take place but is

of a more informal character than in larger

organisations (Cragg, 2002). Although, those that

are able to implement ecommerce may go on to

claim a competitive advantage (Poon, 2000).

The relevance of non financial drivers in ICT

adoption is corroborated by other studies. Buonanno

et al. (2005) found that “[Italian] SMEs disregard

financial constraints as the main cause for ERP

system non adoption, suggesting structural and

organizational reasons as major ones”. Fontana et al.

(2008) found in the adoption of LAN technologies in

Italian SMEs that increased operational efficiency,

ICT USE IN SMES - A Comparison between the North West of England and the Province of Genoa

245

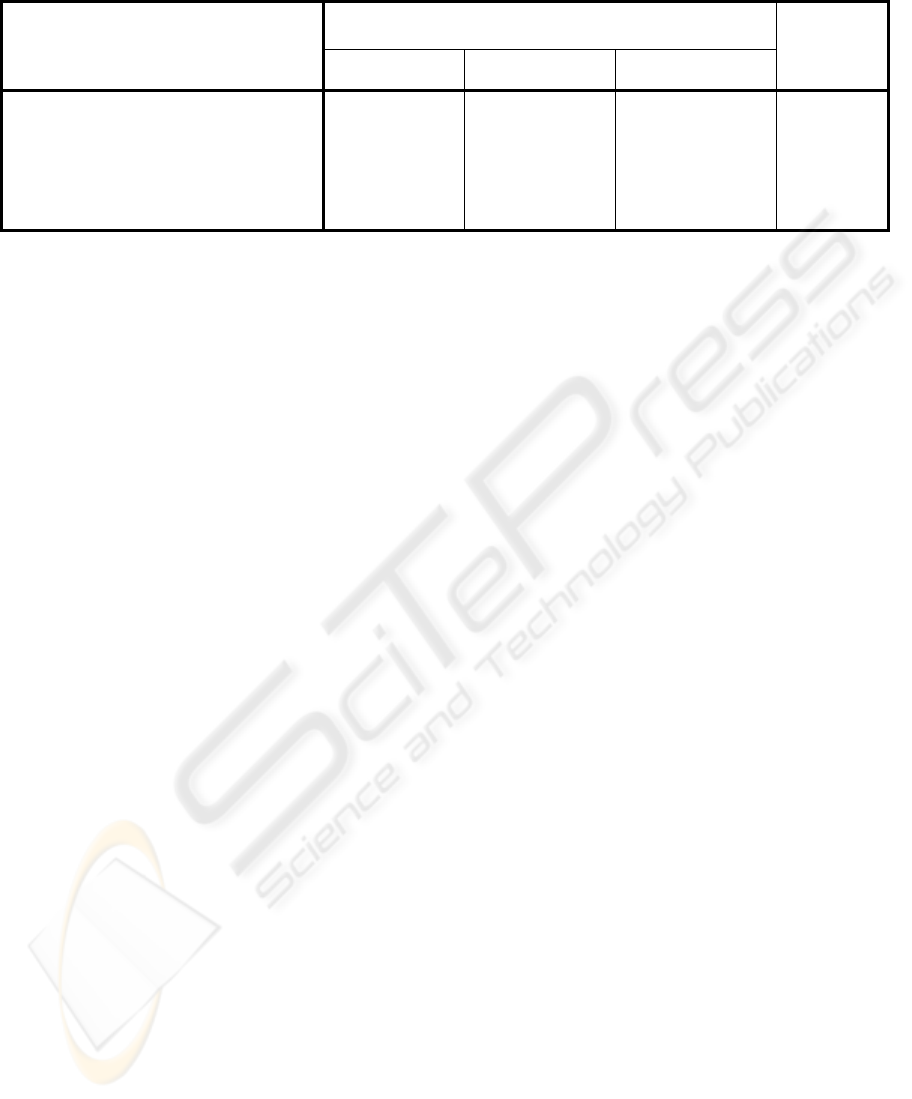

Table 1: Size of Firms by Sector.

technology-based innovation and growth, and better

risk management were the key factors affecting

adoption. In contrast, factors such as cost,

technological uncertainty and lack of relative

advantage seemed to be the most important obstacles

to adoption.

In summary, SMEs in both the UK and Italy

seem to face similar challenges and opportunities in

terms of ICT adoption and use. SMEs in both

contexts are constrained in their technological and

management capabilities and need external sources

of support not merely with the diffusion of new

types of ICT but in terms of building internal

capabilities to innovate using these technologies.

Firms are seen to benefit more when ICT is used

strategically than when ICT is tied to mainly

operational activities.

4 METHODOLOGY

Genoa and the North West of England were chosen

because of their similarities: both are based around

old, once thriving, ports in the process of

regeneration with similar profiles in terms of

business activity. Both look to the SME sector to

provide the employment opportunities once offered

by much larger businesses. Trying to control as

much as possible for the primary regional

characteristics would then allow us to explore

differences in response between the regions as an

outcome of the different business systems, public

policy initiatives, history and traditions between

Italy and England. We chose high tech

manufacturing (SIC 30-33) and food processing as

contrasting sectors both of which are economically

important to the two regions. The density of SME

activity is higher in the Genoa region than in the

immediate environment of Liverpool and this

dictated the wider survey range for the UK part of

this research. In the North West, regions were

selected on a postcode basis and the firms chosen

randomly from a generated list derived from the

FAME (Financial Analysis Made Easy) database,

which provides information on over 3 million

companies in the UK). In Genoa, all joint-stock

SMEs in the selected industries were considered for

the survey, using the AIDA database (the Italian

equivalent to FAME) as a source for contact data.

A questionnaire was constructed comprising 26

questions generally requiring discrete responses. It

asked for details about the business, the extent of

current IT and Internet use (including applications,

benefits and problems), IT investment decisions and

sources of IT supply and advice. We choose closed

ended responses partly to contain differences in

language expression but also because the

questionnaire was to be administered in slightly

different ways in the two regions: telephone

interviews in the North West; an online

questionnaire via email in Genoa with the

respondent filling in the questionnaire themselves.

Simple questions requiring categorical type answers

were thus used in an attempt to reduce respondent

bias. The questionnaire was developed in English

and subsequently translated into Italian.

The questionnaire was first applied in the North

West region in 2007 as part of a larger national

survey (Dyerson et al., 2008) and then applied in

Genoa in 2008. The responses were collated and

brought together into a single data file with 35 firms

for the North West (response rate 7.8%) and 44

firms for Genoa (response rate 41%). These are

relatively small sample sizes and so the results must

be viewed with this limitation in mind. The higher

response rate achieved in Italy may be due to the

convenience and flexibility offered by the Internet to

respondents compared to the telephone method use

in England. It may also be due to better targeting and

the more active follow-up of respondents. In the next

Country

Size of Firm (Number of replies)

Total 0-9 employees 10-49 employees 50-250 employees

UK Sector Manufacturing

3 8 14 25

Food processing

1 5 4 10

Italy Sector Manufacturing

7 18 1 26

Food processing

5 10 3 18

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

246

section we present some of the data from the

surveys, due to space constraints not all results are

discussed.

5 SURVEY RESULTS AND

DISCUSSION

Here we present and discuss the main results arising

from our survey. In doing so, we will highlight

similarities and differences between the SMEs in the

two regions.

5.1 Firm Profile

Most of the replies received were from firms that

have been trading for ten years or more irrespective

of sector. The firms from Genoa display a slightly

younger profile but this is not significant but a

difference exists in terms of firm size. Table 1

indicates that the North West manufacturers were

typically larger than their counterparts in Genoa and

indeed larger than food processors irrespective of

country. The picture is less clear for food processors

although on balance the majority of replies suggest a

size profile of 50 or less employees.

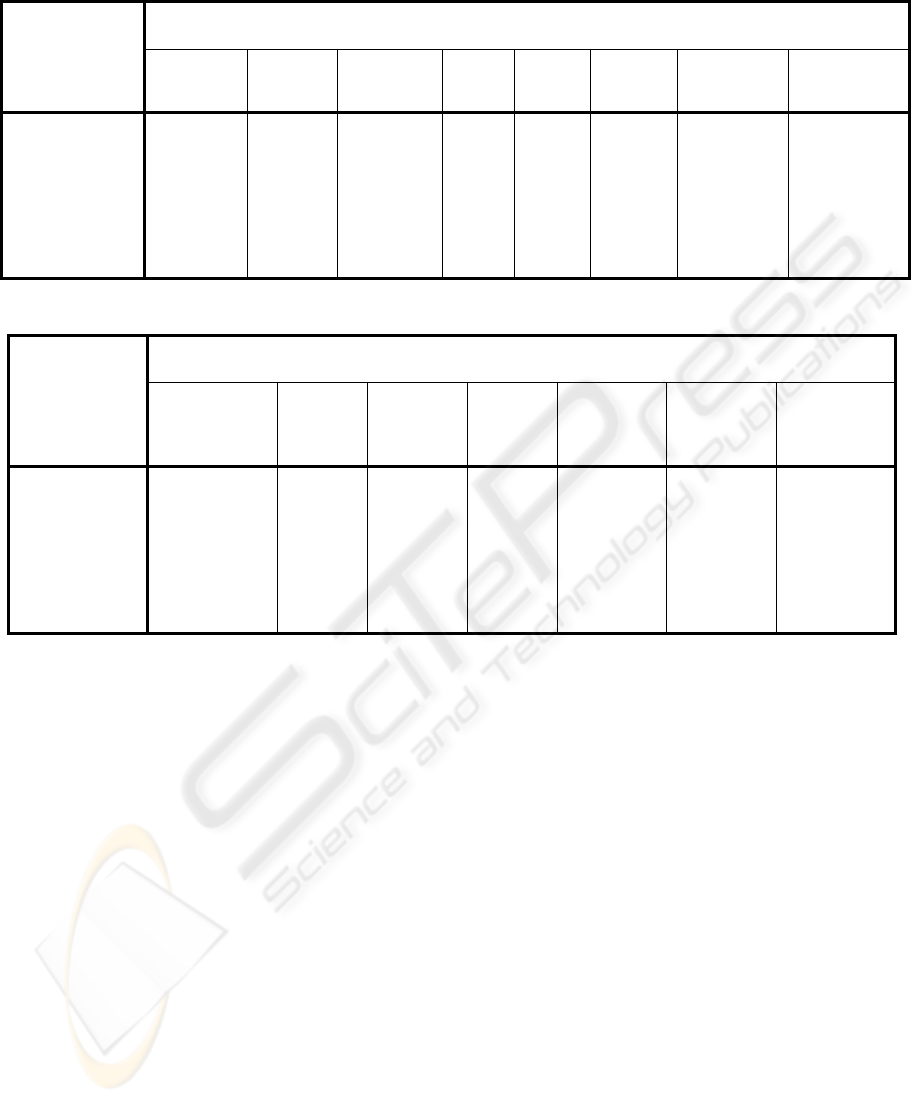

5.2 Types of ICT used

As we would expect, there is a high reported

diffusion of basic ICT such as personal computers,

(all almost 100%). Table 2 shows the technologies

deployed by our survey firms. Here, Italian firms

reported greater diffusion of ICT within basic or

more routine business applications; for example a

greater proportion of Italian firms use ICT to process

orders, record sales, manage stock and

documentation than their English counterparts.

Notable exceptions in this general finding relate to

ERP and market research. Here, English firms

reported greater diffusion of such applications than

the Italian firms, although, as one might expect,

manufacturing firms recorded the highest use of

ERP systems irrespective of region. If ICT diffusion

in terms of basic functions, is generally more

widespread in our Italian firms then specific,

arguably more sophisticated, functions such as

market research and ERP are used more

proportionally by the English firms surveyed.

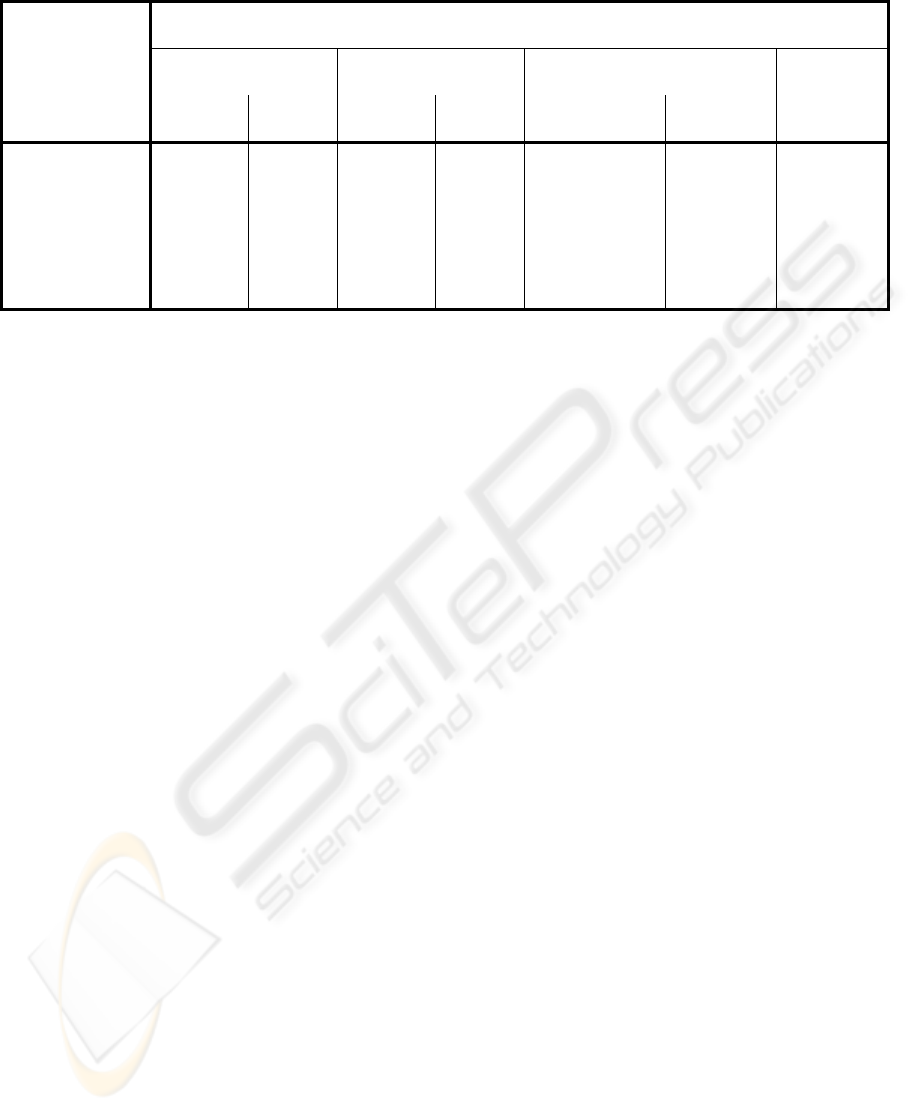

5.3 ICT Benefits

Our survey firms with one exception all report in

high numbers that the greatest single benefit of ICT

is in improving productivity. Results are reported in

Table 3. The exception is the Italian food producers

who see ICT as primarily important in helping to

meet changing regulatory requirements (70% of all

Italian food producers in our survey). English food

producers also see ICT as helpful in this respect

although in not such high proportions (40%).

Perhaps this is not surprising given the European

Union’s emphasis on traceability in food production

but the differing proportional response is more

difficult to explain. Even more puzzling is the

differential response of the manufacturers in our

survey with more than twice the number of Italian

manufacturers citing this as a benefit compared to

the English firms. There is a country divide in two

further aspects of reported benefits. Italian firms in

proportionately greater number cited faster

responses to customers and competitors as benefits.

Italian firms also see ICT as helping to improve staff

satisfaction in far greater proportions than English

firms. Indeed, English manufacturers failed to cite

improved staff satisfaction as a benefit. As a general

rule though, all the SMEs in our survey generally

thought that their ICT represented value for money;

English manufacturers were the most pleased (92%)

and the Italian food producers the least pleased

(76%).

5.4 Factors Influencing ICT

Investment

Our survey suggests that both sets of firms are

preoccupied by similar pressures to increase sales

and reduce their costs. Very few firms wish to

maintain the status quo. Within that broad strategic

pattern, English manufactures appear to want to

expand their number of trading locations and

increase collaboration in contrast to Italian

manufacturers’ intention to increase the number of

markets served. Turning to the food processors,

Italian firms place greater emphasis on reducing

costs and increasing the number of markets served

compared to their English counterparts. This may be

indicative of a greater sensitivity towards exports

than their English counterparts.

The actual benefits reported above broadly

correspond to the SMEs stated reasons for investing

in ICT. Thus for example all the SMEs place

productivity very highly as a motivator for ICT

investment. In this sense, the ex ante motivation and

the ex post experience of ICT are in alignment for

our firms, albeit that our SMEs in general appear to

underestimate the ex post benefits. There are

ICT USE IN SMES - A Comparison between the North West of England and the Province of Genoa

247

Table 2: Applications by Country.

Table 3: ICT Benefits by Country.

however some exceptions. Most Italian food

processors, 88%, for example cite productivity as a

motivator for investment but only 47% report actual

benefits of this kind. This suggests that Italian food

producers may be struggling to exploit productivity

gains from their ICT investment. Similarly, 71% of

English manufacturers cite keeping up with

competitors as a motivation for investment but only

13% report this as an ex post benefit. On the other

hand, 31% and 18% of Italian manufacturers and

food producers cite keeping up with competitors as a

reason for ICT investment but 58% and 41% of

manufacturers and food producers respectively

report this as a benefit. This suggests that Italian

SMEs are underestimating the effect of ICT

Part of the explanation for this mismatch

between expectations and outcomes might lie in the

methods used to evaluate their ICT investment.

When asked whether they used formal techniques to

evaluate their ICT investments there was a striking

country effect in the SMEs responses. The English

food producers (60%) generally used formal

techniques as too did the English manufacturers

although less proportionately (48%). In contrast,

both Italian manufacturers and food processors (88%

respectively) indicated that they did not use formal

techniques to evaluate their investments. At the

same time, 45% and 47% of Italian manufacturers

and food producers respectively were uncertain over

the business benefit of their ICT investment

compared to 33% of English manufacturers and 25%

of food producers. Of those that indicated using

formal techniques, such techniques were typically

conducted not in house but by outside consultants,

especially with respect to the Italian SMEs (79% and

92% of manufacturers and food producers

respectively).

As might be expected, consultants formed the

single largest group to whom the SMEs turned for

advice. Beyond that though, suppliers appeared

popular with the Italian manufacturers and food

producers (48% and 53% respectively) whereas the

English food producers (40%) preferred to use their

own personal networks. English manufacturers by

and large appeared to use ICT consultants (56%)

with far lower dependence on suppliers (24%) or

ICT Applications (% of replies within each sector, rounded)

Order

processing

Sales

recording

Stock and

production

control E.R.P. Design

Market

research

Business

intelligence

Document

management

UK

Manufacturing

67 79 46 63 42 58 63 54

Food processing

70 70 60 70 50 60 50 70

Italy

Manufacturing

96 85 73 19 39 35 62 85

Food processing

77 94 82 12 0 6 35 77

ICT Benefits (% of replies within each sector)

Greater

productivity/

Reducing costs

Improved

product/

service

quality

Faster

response

to

customers

Increased

sales

Improved

staff

satisfaction

Kept up

with

competitors

Kept up with

regulatory

requirements

UK

Manufacturing

87 44 44 22 26 13 17

Food processing

80 40 10 20 0 30 40

Italy

Manufacturing

92 65 85 15 42 56 50

Food processing

47 35 65 12 41 41 71

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

248

personal networks (20%). Perhaps more intriguingly,

just one SME in the entire survey acknowledged

using Government or the local authority as a source

of advice. This pattern is somewhat repeated in

determining the factors important in choosing the

ICT supplier. Here for all but the English food

producers, past experience appeared as important

(running from 63-73% compared to 22% of English

food producers). English food producers reported

personal recommendation (56%) as most important.

Finally, Italian SMEs were also influenced by the

availability of after sales service by their suppliers

(50-60%) compared to the English firms surveyed

(17-22%).

5.5 Internet Applications and Impact

An interesting pattern emerges in internet use by our

survey firms. As Table 4 shows, the Italian

manufacturers reported more extensive use of the

internet than any other grouping. These

manufacturers display high levels of use in sharing

information with customers and suppliers, gathering

information and both trading and making payments

to their suppliers. English manufacturers in

comparison reported very low levels of internet

usage. Both sets of food producers reported high

internet use to gather information. However

although 80% of all the English food SMEs use the

internet to share information both with customers

and suppliers, this is not carried through into

electronic payment. It is also worth pointing out that

very few SMEs in our survey use the internet to

trade with or receive direct payments from

customers – Italian manufacturers making the most

use at 38%. Somewhat surprisingly, given this, it is

the food SMEs that report highest impact: 20% of

English food producers indicated that on line

ordering accounted for 5% or less of total sales and

another 20% indicated that on line sales accounted

for 25% or less; 28% of Italian food producers

indicated that on line sales were up to 5% of their

total sales. In comparison, just 12% of Italian and

8% of English manufacturers reported that on line

sales took up 5% or less of their total sales. It may

be that food products are inherently more tradable

over the internet than the manufactured products

surveyed, although this remains conjecture at

present.

Having noted this, the English firms reported

proportionately greater success in using the internet

to attract sales in addition to existing customers.

Both English manufacturers (53%) and food

producers (56%) found that the internet attracted

new domestic customers. This was not the case for

the Italian SMEs in which just 4% of manufacturers

and no food producers attracted additional domestic

customers. The pattern is repeated in terms of

attracting new international customers in which 27%

of English manufacturers and 33% of food producers

reported additional sales compared to no Italian

manufacturer and just 6% of Italian food SMEs.

Thus, although the English manufacturers reported

less internet use, those that do, report additional

sales both domestically and internationally.

6 CONCLUSIONS

A number of similarities and differences emerge

from our survey of the two regions. While SMEs in

both regions find that ICT offer benefits to their

businesses, much of this benefit remains rooted in

operational matters. Given the mainly long

established nature of the SMEs in our survey this is

disappointing. This is in line with previous studies

on an individual country basis but is the first time to

our knowledge that the two countries have been

explicitly compared.

There are differences in reported behaviour

between the two regions although we have to keep in

mind the exploratory nature of this survey and the

small number of replies. Thus the results have to be

treated with caution and remain to be confirmed in a

larger study. The North West SMEs generally

reported not so high a diffusion of ICT technologies

than the Italian SMEs. On the other hand, the Italian

SMEs appear to be more orientated towards basic

functionality. The indication is that while the Italian

SMEs generally does more with basic ICT, the

English SMEs are more sophisticated in how they

apply ICT. One possible explanation for this is that

English SMEs generally possess greater financial

and human resources to devote to ICT than their

Italian counterparts, although this needs to be

explored further. Certainly, the English SMEs in our

survey tend to spend more than the Italian SMEs -

50% of all the Italian firms spent less than £25k on

ICT in the previous year compared to 32% of all the

English firms.The English SMEs also reported

greater use of formal techniques to evaluate their

ICT investments, perhaps reflecting the larger sums

involved. The Italian SMEs also reported cost as a

concern more frequently than the English SMEs.

More broadly, while the Italian SMEs reported

less sophisticated use of ICT, they were proportiona-

ICT USE IN SMES - A Comparison between the North West of England and the Province of Genoa

249

Table 4: Use of Internet by Country.

tely more proactive in seeking new markets and

complying with new regulations. What remains

unclear is whether this eagerness towards

compliance merely reflects a process of catch up in

relation to the English SMEs. In contrast, the

English SMEs were more concerned with

competition and increasing the number of trading

locations. They appear to have more internal

expertise and wider personal networks to draw on

for help that their Italian counterparts. In contrast,

the Italian SMEs appear more reliant on after sales

support and express greater concerns over staff

attitudes to ICT.

Perhaps as a result, the Italian SMEs are more

enthusiastic about internet’s potential but achieve

less with it than the English SMEs. Thus for

example, the English SMEs are much more

successful in generating additional custom despite a

wariness to adopt on line ordering. For the Italian

SMEs, the internet is having the effect of market

substitution but in for the English SMEs market

extension appears to be happening. So although the

Italian SMEs appear to be more entrepreneurial and

strategic in outlook, it is the English firms that

appear to be achieving practical success. This is an

interesting result but we are mindful that this is an

exploratory study involving just two regions and two

sectors. Further work is required to delve deeper into

the SMEs surveyed to tease out organisational and

cultural factors. In the future we also plan to extend

the analysis into other sectors and other regions to

explore the robustness of these findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and

support of Nammis (http://www.nammis.co.uk) in

helping the survey process for the North West of

England. We would also like to recognise the

financial support received from the Italian National

Research Council (CNR).

REFERENCES

Balocco, R., Mainetti, S. and Rangone, A., 2006. Innovare

e competere con le ICT. Il ruolo delle tecnologie

dell’informazione e della comunicazione nella crescita

delle PMI, Il Sole 24 Ore, Milano.

Benevolo, C. Caselli, L. (Eds.), 2008. La realtà

multiforme delle piccole e medie imprese. il caso della

provincia di Genova, Franco Angeli, Milano.

Buonanno, G., Faverio, P., Pigni, F., Ravarini, A., Sciuto,

D., Tagliavini, M., 2005. Factors Affecting ERP

system adoption. A comparative analysis between

SMEs and large companies. Journal of Enterprise

Information Management, 18 (4), 384-426.

Caselli, L., 2003. Liguria tra sviluppo e emarginazione. In

Ricercare Insieme. Studi in onore di Sergio Vaccà (p.

129), Franco Angeli, Milano.

Cioppi, M., Savelli, E., 2006. ICT e PMI. L’impatto delle

nuove tecnologie sulla gestione aziendale delle piccole

imprese, ASPI/INS-Edit, Urbino & Genova.

Cioppi, M., Savelli, E., Di Marco, I., 2003. Gli effetti delle

ICT sulla gestione delle piccole e medie imprese.

Piccola Impresa/Small Business, (3), 11-50.

Cragg, P., King, M., Hussin, H., 2002. IT alignment and

firm performance in small manufacturing firms.

Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11 (2), 109–

132.

Drew, S., 2003. Strategic use of e-commerce by SMEs in

the East of England. European Management Journal,

21 (1), 79-88.

Dyerson, R., Harindranath, G. and Barnes, D., 2008,

National survey of SMEs’ use of IT in four sectors,

Proceedings of the European Conference on

Information Management and Evaluation, Royal

Use of Internet (% of replies within each sector)

Share information

with: Trade with: Payments:

Information

gathering customers suppliers customers suppliers from customers to suppliers

UK

Manufacturing

56 44 8 12 12 0 28

Food processing

80 80 20 20 10 10 50

Italy

Manufacturing

69 73 38 77 27 81 77

Food processing

56 50 28 22 39 61 89

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

250

Holloway-University of London, Egham, United

Kingdom.

EC (European Commission), 2008. The European e-

Business Report 2006/07, Brussels.

Fontana, R., Corrocher, N., 2008. Objectives, obstacles

and drivers of ICT adoption: What do IT managers

perceive? Information Economics and Policy, 20, 229-

242.

Gramignoli, S., Ravarini, A., Tagliavini, M., 1999. A

Profile for the IT Manager within SMEs. In

Proceedings of the 1999 ACM SIGCPR Conference on

Computer Personnel Research (p. 200), ACM, New

York.

Harindranath, G. Dyerson, R., Barnes, D., 2008, ICT in

small firms: Factors affecting the adoption and use of

ICT in Southeast England SMEs. In Proceedings of

the 16th European Conference on Information

Systems, Galway, Ireland.

Hicks, B.J., Culley, S.J., McMahon, C.A., 2006. A study

of issues relating to information management across

engineering SMEs. International Journal of

Information Management, 26 (4), 267–289.

ISTAT, 2008a. Occupazione e valore aggiunto nelle

province, ISTAT, Roma.

ISTAT, 2008b. Sistema di indicatori territoriali.

[sitis.istat.it]

Levy, M., Powell, P., Galliers, R., 1999. Assessing

information systems strategy development frameworks

in SMEs. Information & Management, 36 (5), 247–

261.

Maguire, S., Koh, S.C.L., Magrys, A., 2007. The adoption

of e-business and knowledge management in SMEs.

Benchmarking: An International Journal, 14 (1), 37-

58.

Marasini, R., Ions, K., Ahmad, A., 2008. Assessment of e-

business adoption in SMEs: A study of manufacturing

industry in the UK North East region. Journal of

Manufacturing Technology Management, 19 (5), 627-

644.

Martin L., Matlay H., 2001. Blanket approaches to

promoting ICT in small firms: Some lessons from the

DTI ladder adoption model in the UK. Internet

Research: Electronic Networking Applications and

Policy, 11 (5), 399–410.

Northwest Regional Development Agency, 2006.

Northwest Regional Economic Strategy. Warrington.

Office of National Statistics, 2007. UK Businesses:

Activity, Size and Location, Her Majesty’s Stationary

Office, London.

Office of National Statistics, 2008. Regional Trends 40,

Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London.

Ordanini, A., 2006. Information Technology and small

business: antecedents and consequences of technology

adoption. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Owens, I.., Beynon-Davies, P., 2001. A survey of

Electronic Commerce utilization in Small and Medium

Sized Enterprises in South Wales. In Proceedings of

The 9th European Conference on Information Systems

,

Bled, Slovenia.

Pavic, S., Koh, S.C.L., Simpson., M., Padmore, J., 2007.

Could e-business create a competitive advantage in

UK SMEs?. Benchmarking: An International Journal,

14 (3), 320-351.

Poon, S., 2000. Business environment and Internet

commerce benefit—a small business perspective.

European Journal of Information Systems, 9, 72–81

Zheng, J, Caldwell, N., Harland, C., Powell, P., Woerndl,

M., Xu S., 2004. Small firms and e-business:

cautiousness, contingency and cost-benefit. Journal of

Purchasing & Supply Management, 10, 27–39.

ICT USE IN SMES - A Comparison between the North West of England and the Province of Genoa

251