DISTINGUISHING KNOWLEDGE FROM INFORMATION

A Prerequisite for Elaborating KM Initiative Strategy

Michel Grundstein

MG Conseil, 4 rue Anquetil, 94130 Nogent sur Marne, France

Paris Dauphine University, Place du Maréchal De Lattre de Tassigny 75775 Paris, France

Keywords: Information, Knowledge, Knowledge Management (KM), Individual’s tacit knowledge, Commensurability

of Individual’s Interpretative Frameworks, KM initiative strategy, Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge

System (EIKS).

Abstract: Although the technological approach of Knowledge Management (KM) is greatly shared, without

awareness, when elaborating KM initiative’s strategy, we can confuse the notions of information and

knowledge, and disregard the importance of individual’s tacit knowledge used in action. Therefore, to avoid

misunderstanding during the strategic orientation phase of a general KM initiative development, it is

fundamental to clearly distinguish the notion of information from the notion of knowledge. Further, we

insist on the importance to integrate the individual as a component of the Enterprise’s Information and

Knowledge System (EIKS). In this paper, we argue that Knowledge cannot be considered as an object such

as data are in digital information systems. Consequently, we propose an empirical model enabling to

distinguish the notions of information and knowledge. This model shows the role of individual’s

interpretative frameworks and tacit knowledge, establishing a discontinuity between information and

knowledge. This pragmatic vision needs thinking about the architecture of an Enterprise’s Information and

Knowledge System (EIKS), which must be a basis of discussion during the strategic orientation phase of a

KM initiative.

1 INTRODUCTION

Very often, Knowledge Management (KM) is

considered from a technological viewpoint. That

practice induces to consider knowledge as an object

independent of individuals. In that way, as

information, knowledge can be acquired, processed,

stocked, transmitted and restored. However, we

argue that as soon as knowledge is explicit,

formalized and codified in a Digital Information

System (DIS), it becomes information. We call that

information “information source of knowledge for

somebody.” Effectively, individual’s tacit

knowledge is involved to enable the user to give a

sense to that information in order to act. As noticed

by Wiig (2008) “Without knowledge, intelligent and

effective behaviour – the ability to interpret, assess,

understand, innovate, decide, act, and monitor – will

not be possible even if the best information is made

available (p.2).” However, if information can be

acquired, processed, stocked, transmitted and

restored, such is not the case for individual’s tacit

knowledge used in action.

Although the technological approach is greatly

shared, without awareness, when elaborating KM

initiative’s strategy, we can confuse the notions of

information and knowledge, and disregard the

importance of individual’s tacit knowledge used in

action. Therefore, to avoid misunderstanding during

the strategic orientation phase of a Knowledge

Management initiative, it is fundamental to clearly

distinguish the notion of information from the notion

of knowledge. Further, we insist on the importance

to integrate the individual as a component of the

Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge System

(EIKS).

In this paper, after having put down background

theory and assumptions, we propose an empirical

model enabling to distinguish the notions of

information and knowledge. This model shows the

role of individual’s interpretative frameworks and

tacit knowledge, establishing a discontinuity

between information and knowledge. This pragmatic

135

Grundstein M. (2009).

DISTINGUISHING KNOWLEDGE FROM INFORMATION - A Prerequisite for Elaborating KM Initiative Strategy.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, pages 135-140

DOI: 10.5220/0002289001350140

Copyright

c

SciTePress

vision needs thinking about the architecture of an

Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge System

(EIKS), which must be a basis of discussion during

the KM initiative’s strategic orientations phase.

2 BACKGROUND THEORY AND

ASSUMPTIONS

2.1 Creation of Individual’s Tacit

Knowledge

Our approach is built upon the assumption

emphasized by Tsuchiya (1993)

concerning

knowledge creation ability. He states, “Although

terms ‘datum’, ‘information’, and ‘knowledge’ are

often used interchangeably, there exists a clear

distinction among them. When datum is sense-given

through interpretative framework, it becomes

information, and when information is sense-read

through interpretative framework, it becomes

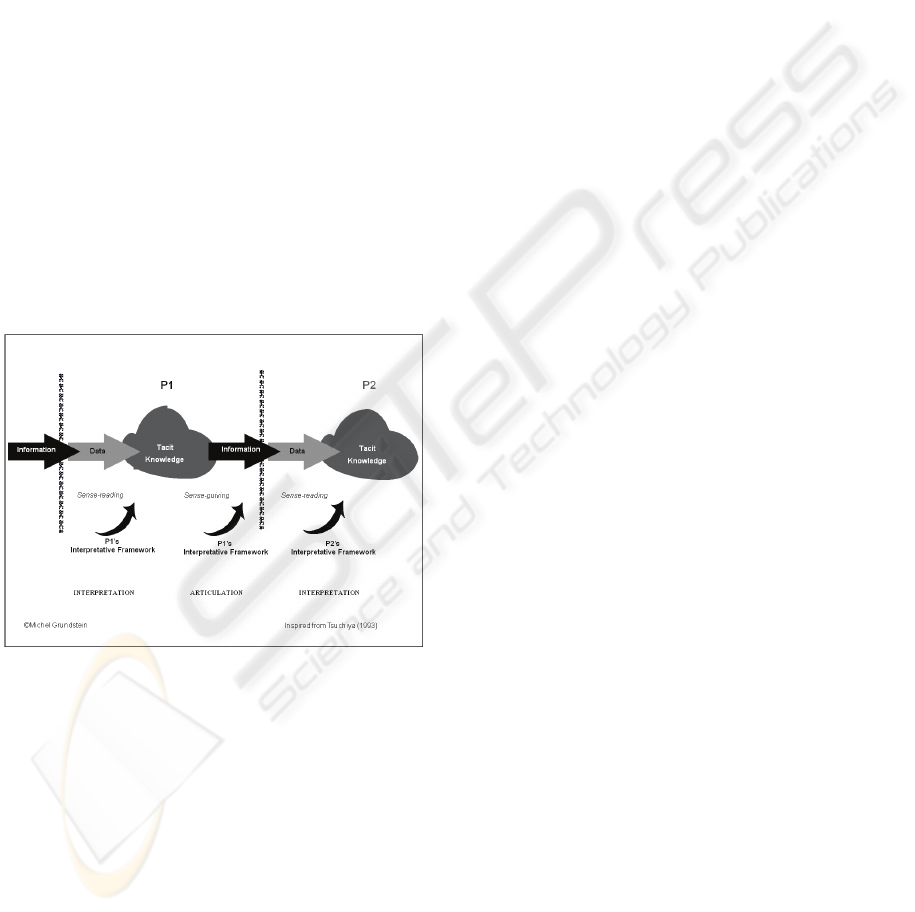

knowledge (p.88)”. Figure 1 represents our own

interpretation of Tsuchiya’s assumption.

Figure 1: Creation of individual's tacit knowledge.

In other words, we can say that tacit knowledge

that resides in our brain results from the sense given,

through our interpretative frameworks, to data that

we perceive among the information transmitted to

us. Or rather, Knowledge exists in the interaction

between an Interpretative Framework (incorporated

within the head of an individual, or embedded into

an artefact), and data.

Consequently, we postulate that knowledge is

not an object processed independently of the person

who has to act. So, we can say that formalized and

codified knowledge, that are independent from

individual, are not more than information.

Furthermore, as emphasized by Haeckel (2000) we

must discern “the knowledge of knower and the

codification of that knowledge (p. 295).”

2.2 Definition of Knowledge

Management (KM)

In 1990, the Initiative for Managing Knowledge

Assets (IMKA, 1990) was initiated by a few

companies (Carnegie Group, Inc., Digital Equipment

Corporation, Ford Motor Company, Texas

Instruments, Inc., and US WEST Advanced

Technologies, Inc.). They defined for the first time

the notion of knowledge assets: “Knowledge assets

are those assets that are primary in the minds of

company's employees. They include design

experience, engineering skills, financial analysis

skills, and competitive knowledge.”

Gradually, numerous research works were

carried out, enterprise’s KM initiatives were

deployed, and an abundant literature enriched the

domain of Knowledge Management. So that the

concept of KM highlighted a broad range of topics

and became a fuzzy concept taking as many senses

as people speaking about it. For instance, in his

editorial preface, untitled “What is Knowledge

Management?” Jennex (2005) has gathered some

authors’ definitions that show that there is no

common evidence about what KM is. Regan (2007)

consolidates this observation. She states, “This lack

of agreement on a definition of knowledge

management seems atypical for an emerging

discipline that traces its roots back at least two

decades. Even the most recent textbooks in the field

spend an entire chapter just explaining what

knowledge management is and what it is not, and

provide an entire page of definitions.”

The introduction to KMIS 2009 conference

shows the same understanding: “There are several

perspectives on KM, but all share the same core

components, namely: People, Processes and

Technology. Some take a techno-centric focus, in

order to enhance knowledge integration and

creation; some take an organizational focus, in order

to optimize organization design and workflows;

some take an ecological focus, where the important

aspects are related to people interaction, knowledge

and environmental factors as a complex adaptive

system similar to a natural ecosystem.”

We can add that most of time, KM is considered

from a technological viewpoint. For example, let’s

consider the European Project Team in charge to

elaborate The European Guide to Good Practice in

Knowledge Management on behalf of the European

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

136

Committee for Standardization Workshop on

Knowledge Management. This Workshop was

running from September 2002 till September 2003.

The Project Team has collected, categorized and

analyzed more than 140 KM Frameworks. It may be

noted that this work has produced a high-quality

practical outcome that can be used as a reference

point to achieve a good understanding of KM (CEN-

1, 2004). Nevertheless, as contributors to this

project, we observed that few of them were “people-

focused” as highlighted by Wiig (2004). We can

underline the predominant positivist paradigm and

the technological approach of KM that have inspired

the project team. As a result, the authors consider a

system of interrelated objects that can be described

independently of individual. That has induced them

to consider the knowledge as an object, and so to

disregard the importance of people.

Furthermore we distinguished two main

approaches underlying KM: (i) a technological

approach that answers a demand of solutions based

on the technologies of information and

communication (ICT); and (ii) a managerial and

sociological approach that integrates knowledge as

resources contributing to the implementation of the

strategic vision of the company. On the one hand,

the technological approach leads to reduce

knowledge to codified knowledge that is no more

than information. In that case KM initiatives can be

managed in the same way than Information System

projects. On the other hand, the managerial and

sociological approach that integrates knowledge as a

resource is centered on the core business processes,

and people.

In our research group, relying on Tsuchiya’s

works (Tsuchiya, 1993) we argue that knowledge is

dependent of the individual’s interpretative

framework, and the context of his action.

Consequently, knowledge resides primarily in the

heads of individuals, and in the social interactions of

these individuals. It cannot be consider as an object

such as data are in digital information systems.

Thus, it appears that KM addresses activities, which

utilize and create knowledge more than knowledge

by itself. With regard to this question, since 2001,

our group of research has adopted the following

definition of KM (Grundstein and Rosenthal-

Sabroux, 2003): “KM is the management of the

activities and the processes that enhance the

utilization and the creation of knowledge within an

organization, according to two strongly interlinked

goals, and their underlying economic and strategic

dimensions, organizational dimensions, socio-

cultural dimensions, and technological dimensions:

(i) a patrimony goal, and (ii) a sustainable

innovation goal (p.980).” The patrimony goal has to

do with the preservation of knowledge, their reuse

and their actualization; it is a static goal. The

sustainable innovation goal is more dynamic. It is

concerned with organizational learning that is

creation and integration of knowledge at the

organizational level.

3 DISTINGUISHING THE

NOTIONS OF INFORMATION

AND KNOWLEDGE

Numerous authors analyzed the notions of data,

information and knowledge. Let us quote notably

Davenport and Prusak (1998, pp.1-6)), Sena and

Shani (1999), Takeuchi, and Nonaka, (2000), Amin,

and Cohendet, (2004, pp. 17-30), Laudon and

Laudon, (2006, p. 416). Besides, Snowden (2000,)

makes the following synthesis: “The developing

practice of knowledge management has seen two

different approaches to definition; one arises from

information management and sees knowledge as

some higher-level order of information, often

expressed as a triangle progressing from data,

through information and knowledge, to the apex of

wisdom. Knowledge here is seen as a thing or entity

that can be managed and distributed through

advanced use of technology…The second approach

sees the problem from a sociological basis. These

definitions see knowledge as a human capability to

act (pp. 241-242).”

Here, one must think “Wisdom” as the level of

the “collective, application of knowledge in action”

(Sena 1999, p.8-4), or as “the collective and

individual experience of applying knowledge to the

solution of problems (Laudon and Laudon 2006, p.

416).”

In the following paragraphs, we clarify our

approach.

3.1 Commensurability of Interpretative

Frameworks and Individual

Sense-Making

Tsuchiya emphases how organizational knowledge

is created through dialogue, and highlighted how

“commensurability” of the interpretative

frameworks of the organization’s members is

indispensable for an organization to create

organizational knowledge for decision and action.

Here, commensurability is the common space of the

DISTINGUISHING KNOWLEDGE FROM INFORMATION - A Prerequisite for Elaborating KM Initiative Strategy

137

set of interpretative frameworks of each member

(e.g. cognitive models or mental models directly

forged by education, experience, beliefs, and value

systems). Tsuchiya states “It is important to clearly

distinguish between sharing information and sharing

knowledge. Information becomes knowledge only

when it is sense-read through the interpretative

framework of the receiver. Any information

inconsistent with his interpretative framework is not

perceived in most cases. Therefore,

commensurability of interpretative frameworks of

members is indispensable for individual knowledge

to be shared (p. 89).”

Therefore, we consider information as

knowledge when members having a large

commensurability of their set of interpretative

frameworks commonly understand it. In that case,

we call it “information source of knowledge for

someone.” Such is the case for members having the

same technical or scientific education, or members

having the same business culture. In these cases,

formalized and codified knowledge make the same

sense for each member. However, one must take into

account that interpretative frameworks evolve in a

dynamic way: they are not rigid mindsets.

Especially, when considering that, as time is going

on, contexts and situations evolve. Thus, the

contribution of scientific results, techniques and new

methods, the influence of young generations being

born with Web (Y generation or Digital Native), the

impact of identity crisis and multiple cultures,

modify the interpretative frameworks, and create a

gap between individuals’ commensurability of

interpretative frameworks.

3.2 From Data to Individual’s Tacit

Knowledge

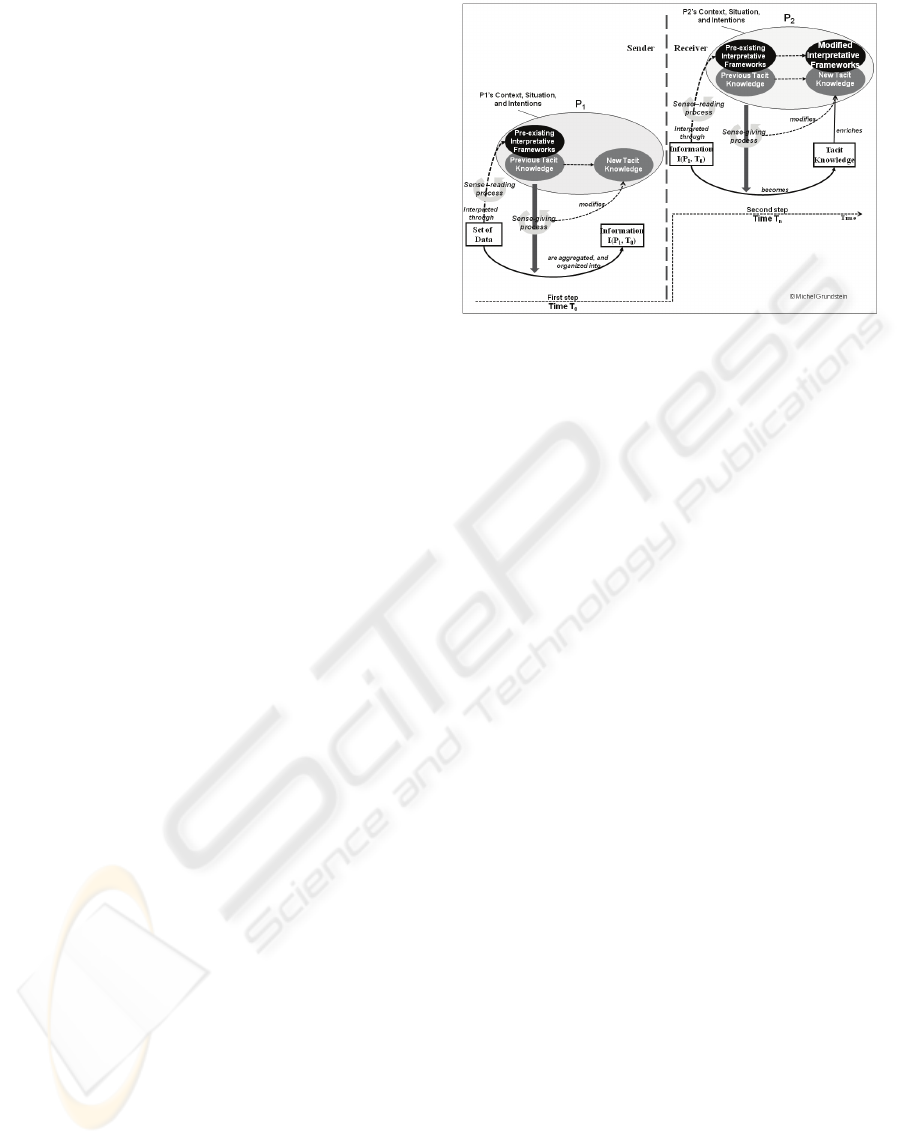

Let’s consider two individuals P

1

and P

2

acting in

different contexts and situations, at different points

in time (Fig. 2).

While P

1

’s previous knowledge is necessary for

elaborating information from data gathered and

filtered in the present time, once created this

information becomes a frozen object. This static

object is independent from P

1

, and time. Then, at

another time, when this information is captured by

P

2

, only some data contained in the information are

selected and interpreted, taking sense for P

2

. In that

way, the P

2

’s tacit knowledge is modified.

Figure 2: From Data…to Individual’s Tacit Knowledge.

In a first step, P

1

, in his context and situation,

gathers a set of data outside him. Then, during a

sense-reading process that depends of his pre-

existing interpretative frameworks activated

depending of his context, his situation, and his

intentions, he selects some of these data that take

sense for him. In the same time, a sense-giving

process using P

1

’s previous tacit knowledge enables

P

1

to aggregate, and organize selected data he

perceived, into information. It is this information

that is passed on by the individuals, or by means of

the DIS where it is stored, treated and transmitted as

a stream of digital data. During this process, P

1

’s

pre-existing interpretative frameworks are not

changing; previous tacit knowledge can be

reorganized and modified into new tacit knowledge.

In a second step, this information is captured by

P

2

. According to his own context and situation, P

2

,

during a process of sense-reading, interprets this

information filtering data through his pre-existing

interpretative frameworks activated depending of his

context, his situation, and his intentions. In the same

time a sense-giving process that uses P

2

’s previous

knowledge operates, and engenders new tacit

knowledge. That’s the way that changes P

2

’s pre-

existing framework and enriches P

2

’s previous tacit

knowledge enabling P

2

to understand his situation,

identify a problem, find a solution, decide, and act.

The results of these processes are modified

interpretative frameworks, and new tacit knowledge.

The process of transformation of data into

knowledge is a process of construction of

knowledge. Created knowledge, can be very

different from one individual to another when the

commensurability of their interpretative frameworks

is small, whatever are the causes of it. There are

large risks that the same information takes different

senses for each of them, and consequently generates

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

138

a construction of different tacit knowledge in the

head of the decision process stakeholders. Unlike the

information, knowledge is dynamic. Once

constructed it cannot be considered as an object

independent from the individual who built it, or the

individual who appropriates it to make a decision

and to act.

As a result one can understand the importance to

clearly distinguish static factual information, which

allows describing the context and the situation that

raise a problem, from the knowledge of the

individual who processes this information to learn

and get knowledge he needs to carry out his tasks.

To answer this issue, distinguishing information

from knowledge leads to conceive what we call

Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge Systems

(EIKS).

4 ENTERPRISE’S

INFORMATION AND

KNOWLEDGE SYSTEM (EIKS)

The enterprise’s information and knowledge system

(EIKS) consists mainly in a set of individuals and

digital information systems. EIKS rests on a socio-

technical fabric, which consists of individuals in

interaction among them, with machines, and with the

very EIKS. It includes (Fig. 3):

• A Digital Information Systems (DIS),

which are artificial systems, the artifacts

designed from information and

communication technologies (ICT)

• An information system constituted by

individuals who, in a given context, are

processors of data to which they give a

sense under the shape of information. This

information, depending of the case, is

passed on, remembered, treated, and

diffused by them or by the DIS.

• A knowledge system, consisting of tacit

knowledge embodied by the individuals,

and of explicit knowledge formalized and

codified on any shape of supports

(documents, video, photo, digitized or not).

Under certain conditions, digitized

knowledge is susceptible to be memorized,

processed and spread with the DIS. In that

case, knowledge is no more than

information.

Figure 3: The Enterprise’ s Information and Knowledge

System (EIKS).

If “Technology provides the possibility of

making information available across time and space”

(Kautz and Kjaergaard 2008, p. 49 ) we always have

to keep in mind, paraphrasing these authors, “the

role of individual in the knowledge sharing process,

but we do also pay attention to how individual use

technology to share knowledge (p. 43).” So,

considering EIKS, we insist on the importance to

integrate the individual as a component of the

system (Grundstein, 2007, pp. 243-247). Three

natures of information must be distinguished: the

Mainstream-Data, the Source-of-Knowledge-Data,

and the Shared-Data (Grundstein and Rosenthal-

Sabroux, 2003, pp. 980-981). Among the tools, the

Information and Knowledge Portals supply a global

access to the information, and can meet the needs of

Knowledge Sharing. In that case, the functional

software and the tools answering the aim of KM are

integrated into the DIS.

5 PROSPECTS

When launching a KM initiative, the Strategic

Orientation Phase is crucial and can avoid to get KM

resources go unused as noticed by Stewart (Stewart,

2002) “One flaw in knowledge management is that it

often neglects to ask what knowledge to manage and

to what end (p.117).” We should add that KM is

often oriented towards Information and

Communication Technologies (ICT) that leads

confusing notions of information and knowledge,

and misunderstanding the goals: do we have to

develop an Information System or do we have to

implement a KM System? Therefore, the Strategic

Orientation Phase must help to build a general KM

vision that makes a clear distinction between

DISTINGUISHING KNOWLEDGE FROM INFORMATION - A Prerequisite for Elaborating KM Initiative Strategy

139

technology as a support to share individual’s tacit

knowledge, and technology as a means to collect,

store, and distribute explicit and codified knowledge

that is no more than information (see § 2.1).

Distinguishing Information from Knowledge

open our mind on a different view of information

systems that leads to conceive what we call

Enterprise’s Information and Knowledge Systems

(EIKS). These systems include individuals and are

based on Digital Information System (DIS). This

pragmatic vision needs thinking about the

architecture of an Enterprise’s Information and

Knowledge System (EIKS), which must be a basis

of discussion during the strategic orientation phase

of a General KM Initiative.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Camille Rosenthal Sabroux and

Virginie Goasdoue whose continuous contribution

and relevant questioning encouraged me to clarify

and improve the model presented in this paper.

REFERENCES

Amin, A., Cohendet P., 2004. Architectures of

Knowledge, firms, capabilities, and communities. New

York US: Oxford University Press Inc.

CEN-1, 2004. Knowledge Management Framework. In

European Guide to Good Practice in Knowledge

Management (Part 1). Brussels: CEN, CWA 14924-

1:2004 (E). Retrieved June 19, 2004, from

ftp://cenftp1.cenorm.be/PUBLIC/CWAs/e-

Europe/KM/CWA14924-01-2004-Mar.pdf

Davenport T. H., Prusak L., 1998. Working Knowledge.

Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Grundstein M., Rosenthal-Sabroux C., 2003. Three Types

of Data For Extended Company’s Employees: A

Knowledge Management Viewpoint. In M. Khosrow-

Pour (Ed.), Information Technology and

Organizations: Trends, Issues, Challenges and

Solutions, 2003 IRMA Proceedings (pp. 979-983).

Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing.

Grundstein M., 2007. Knowledge Workers as an Integral

Component in Global Information System Design. In

Wai K. Law (Ed.), Information Resources

Management: Global Challenges (Chapitre XI, pp.

236-261). Hershey PA: Idea Group Publishing, 2007.

IMKA, 1990. IMKA Technology Technical Summary,

July 30, 1990. IMKA project was formed by Carnegie

Group, Inc., Digital Equipment Corporation, Ford

Motor Company, Texas Instruments Inc., and US

West Advanced Technologies Inc.

Haeckel, S., H., 2000. Managing Knowledge in Adaptive

Enterprises. In C. Despres and D. Chauvel (Eds),

Knowledge Horizons (chap. 14, pp. 287-305).

Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Jennex, M. E., 2005. What is Knowledge Management?

International Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol.1 No.4, pp. i-v. Hershey PA: Idea Group

Publishing.

Kautz, K., Kjaergaard, A., 2008. Knowledge Sharing in

Software Development. In P. A. Nielsen and K., Kautz

(Eds), Software Processes & Knowledge. Beyond

Conventional Software Process Improvement (Chapter

4, pp.43-68 ). Aalborg, Denmark: Software

Innovation Publisher, Aalborg University.

KMIS 2009. International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing. Madeira,

Portugal. Extracted, from http://www.ickm.ic3k.org/

April 2009

Laudon K C, Laudon J P., 2006. Management Information

Systems; Managing the Digital Firm. Upper Saddle

River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc, (Ninth

edition).

Regan, E.A., 2007. Knowledge Management: Evolving

Concept and Practice. The International Journal of

Knowledge, Culture and Change Management,

Volume 6, Issue 9, pp.11-24).

http://www.Management-Journal.com

Sena J.A., Shani A.B., 1999. Intellectual Capital and

Knowledge Creation: Towards an Alternative

Framework. In J. Liebowitz (Ed.), Knowledge

Management Handbook (chapter 6, pp. 6.1-6.29).

Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press LLC.

Snowden, D., 2000. The Social Ecology of Knowledge

Management. In C. Despres & D. Chauvel (Eds)

Knowledge Horizons (chap. 12, pp. 237-365).

Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Stewart, Th. A., 2002. The Wealth of Knowledge:

Intellectual Capital and the 21tst century Organization.

New York, USA: Currency Doubleday.

Takeuchi H., Nonaka, I., 2000. Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation. In D. Morey, M. Maybury, B.

Thuraisingham (Eds), Knowledge management,

Classic and Contemporary Works (Chapter 6, pp. 139-

182). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Tsuchiya S., 1993. Improving Knowledge Creation Ability

through Organizational Learning. ISMICK'93

Proceedings, International Symposium on the

Management of Industrial and Corporate Knowledge,

UTC, Compiègne, October 27-28, 1993.

Wiig, K., 2004. People-Focused Knowledge Management.

How Effective Decision Making Leads to Corporate

Success. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-

Heinemann.

Wiig, K., 2008. Knowledge Management for the

Competent Enterprise. Business Intelligence Vol. 8,

No. 10. Cutter Consortium.

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

140