ONTOLOGICAL CLIQUES

Analogy as an Organizing Principle in Ontology Construction

Tony Veale and Guofu Li

School of Computer Science and Informatics, University College Dublin, Ireland

Keywords: Analogy, Mapping, Cliques, Text analysis, Ontology induction, Google n-grams.

Abstract: Ontology matching is a process that can be sensibly applied both between ontologies and within ontologies.

The former allows for inter-operability between agents using different ontologies for the same domain,

while the latter allows for the recognition of analogical symmetries within a single ontology. These

analogies indicate the presence of higher-order similarities between instances or categories that should be

reflected in the fine-grained structure of the ontology itself. In this paper we show how analogies between

categories in the same ontology can be detected via linguistic analysis of large text corpora. We also show

how these analogies can be clustered via clique-analysis to create meaningful new category structures in an

ontology. We describe experiments in the context of a large ontology of proper-named entities called

NameDropper, and show how this ontology and its analogies are automatically acquired from web corpora.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ontologies, like languages, are meant to be shared.

A common ontology allows multiple agents to share

the same specification of a conceptualization

(Gruber, 1993), ensuring mutual intelligibility when

communicating in the same domain of discourse.

But like languages, there are often many to choose

from: each ontology is a man-made artifact that

reflects the goals and perspective of its engineers

(Guarino, 1998), and different ontologies can model

a domain with differing emphases, at differing levels

of conceptual granularity. Inevitably, then, multiple

agents may use different ontologies for the same

domain, necessitating a mapping between ontologies

that permits communication, much like a translator

is required between speakers of different languages.

Given the operability problems caused by

semantic heterogeneity, the problem of matching

different ontologies has received considerable

attention in the ontology community (e.g., see

Euzenat and Shvaiko, 2007). Fortunately, formal

ontologies have several properties that make

matching possible. Though formal in nature,

ontologies can also be seen as ossified linguistic

structures that borrow their semantic labels from

natural language (De Leenheer and de Moor, 2005).

It is thus reasonable to expect that corresponding

labels in different ontologies will often exhibit

lexical similarities that can be exploited to generate

match hypotheses. Furthermore, since ontologies are

highly organized structures, we can expect different

correspondences to be systematically related. As

such, systems of matches that create isomorphisms

between the local structures of different ontologies

are to be favored over bags of unrelated matches that

may may lack coherence. In this respect, ontology

matching has much in common with the problem of

analogical mapping, in which two different

conceptualizations are structurally aligned to

generate an insightful analogy (Falkenhainer, Forbus

and Gentner, 1989). Indeed, research in analogy

(ibid) reveals how analogy is used to structurally

enrich our knowledge of a poorly-understood

domain, by imposing upon it the organization of one

that is better understood and more richly structured.

Likewise, the matching and subsequent integration

of two ontologies for the same domain may yield a

richer model than either ontology alone.

If we view ontology-matching and analogical-

mapping as different perspectives on the same

structural processes, then it follows that matching

can sensibly be applied both between ontologies (to

ensure inter-operability) and within ontologies (to

increase internal symmetry). When applied within a

single ontology, matching should allow us to

identify pockets of structure that possess higher-

order similarity that is not explicitly reflected in the

34

Veale T. and Li G. (2009).

ONTOLOGICAL CLIQUES - Analogy as an Organizing Principle in Ontology Construction.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development, pages 34-41

DOI: 10.5220/0002297900340041

Copyright

c

SciTePress

ontology’s existing category structure. As such,

these analogies should permit the creation of a new

layer of structure in the ontology, to better reflect

human intuitions about the pragmatic similarity of

different categories and entities.

This paper has several related goals. First, we

demonstrate how analogical mappings can be

derived from corpora for large ontologies that are

themselves induced via text analysis. Second, we

show how this system of analogical mappings can

itself be subjected to further structural analysis, to

yield cliques of related mappings. Third, we show

how cliques can act as higher-level categories in an

ontology, to better capture the intuitions of end-users

(as reflected in their use of language) about which

categories and entities are more similar than others.

We begin in section 2 with a consideration of the

clustering role of categories in ontologies, and how

the graph-theoretic notion of a clique can also fulfil

this role, both at the level of instances and

categories. In section 3 we describe the induction of

our test ontology, called NameDropper, from the

text content of the web. In section 4 we then show

how analogical mappings between the categories of

NameDropper can also be extracted automatically

from web content. This network of analogical

mappings provides the grist for our clique analysis

in section 5, in which we show how analogical

cliques – tightly-knit clusters of mappings between

ontological categories – can be created to serve as

new upper-level categories in their own right. We

conclude with some final thoughts in section 6.

2 CATEGORIES AND CLIQUES

The taxonomic backbone of an ontology is a

hierarchical organization of categories that serves to

cluster ideas (both sub-categories and instances)

according to some intrinsic measure of similarity. In

the ideal case, ideas that are very similar will thus be

closer together – i.e., clustered under a more specific

category – than ideas that have little in common. It

follows that ontologies which employ more

categories can thus make finer distinctions that

better reflect the semantic intuitions of an end-user

(e.g., see Veale, Li and Hao, 2009).

Compare, for instance, the taxonomy of noun-

senses used by WordNet (Fellbaum, 1998) with that

of HowNet (Dong and Dong, 2006). In WordNet,

the category of {human, person} is divided into a

few tens of sub-types, which are themselves further

sub-divided, to hierarchically organize the different

kinds and roles of people that one might encounter.

In HowNet, however, every possible kind of person

is immediately organized under the category Human,

so that thousands of person-kinds share the same

immediate hypernym. For this reason, WordNet

offers a more viable taxonomic basis for estimating

the semantic similarity of two terms, as used in

various ways by Budanitsky and Hirst (2006).

Nonetheless, it is important to distinguish

between semantic similarity and pragmatic

comparability. The measures described by

Budanitsky and Hirst (2006) estimate the former,

and assign a similarity score to any pair of terms

they are given, no matter how unlikely it is that a

human might every seek to compare them.

Comparability is a stronger notion than similarity: it

requires that a human would consider two ideas to

be drawn from the same level of specificity, and to

possess enough similarities and differences to be

usefully compared. There is thus a pragmatic

dimension to comparability that is difficult to

express in purely structural terms. However, we can

sidestep these difficulties by instead looking to how

humans use language to form clusters of comparable

ideas. This will allow us to replace the inflexible

view of ontological categories as clusters of

semantically-similar ideas with the considerably

more flexible view of categories as clusters of

pragmatically-comparable ideas.

It has been widely observed that list-building

patterns in language yield insights into the

ontological intuitions of humans (e.g., see Hearst,

1992; Widdows and Dorow, 2002; Veale, Li and

Hao, 2009). For instance, the list “hackers, terrorists

and thieves”, which conforms to the pattern “Nouns,

Nouns and Nouns”, tells us that hackers, terrorists

and thieves are all similar, are all comparable, and

most likely form their own sub-category of being

(e.g., such as a sub-category of Criminal). We can

build on this linguistic intuition by collecting all

matches for the pattern “Nouns and Nouns” from a

very large corpus, such as the Google n-grams

(Brants and Franz, 2006), and use these matches to

create an adjacency matrix of comparable terms. If

we then find the maximal cliques that occur in the

corresponding graph, we will have arrived at a

pragmatic understanding of how the terms in our

ontology should cluster into categories if these

categories are to reflect human intuitions.

A clique is a complete sub-graph of a larger

graph, in which every vertex is connected to every

other (Bron and Kerbosch, 1973). A k-clique is thus

a complete sub-graph with k vertices; a clique is

maximal if it is not a proper-subset of another clique

in the same graph. In ontological terms then, a clique

ONTOLOGICAL CLIQUES - Analogy as an Organizing Principle in Ontology Construction

35

can represent a category in which every member has

an attested affinity with every other, i.e., a category

in which every member can be meaningfully

compared with every other. Since all ontologies are

graphs, the idea of a clique thus has a certain

semantic resonance in ontologies, leading Croitoru

et al., (2007) to propose cliques as a graph-theoretic

basis for estimating the similarity of two ontologies.

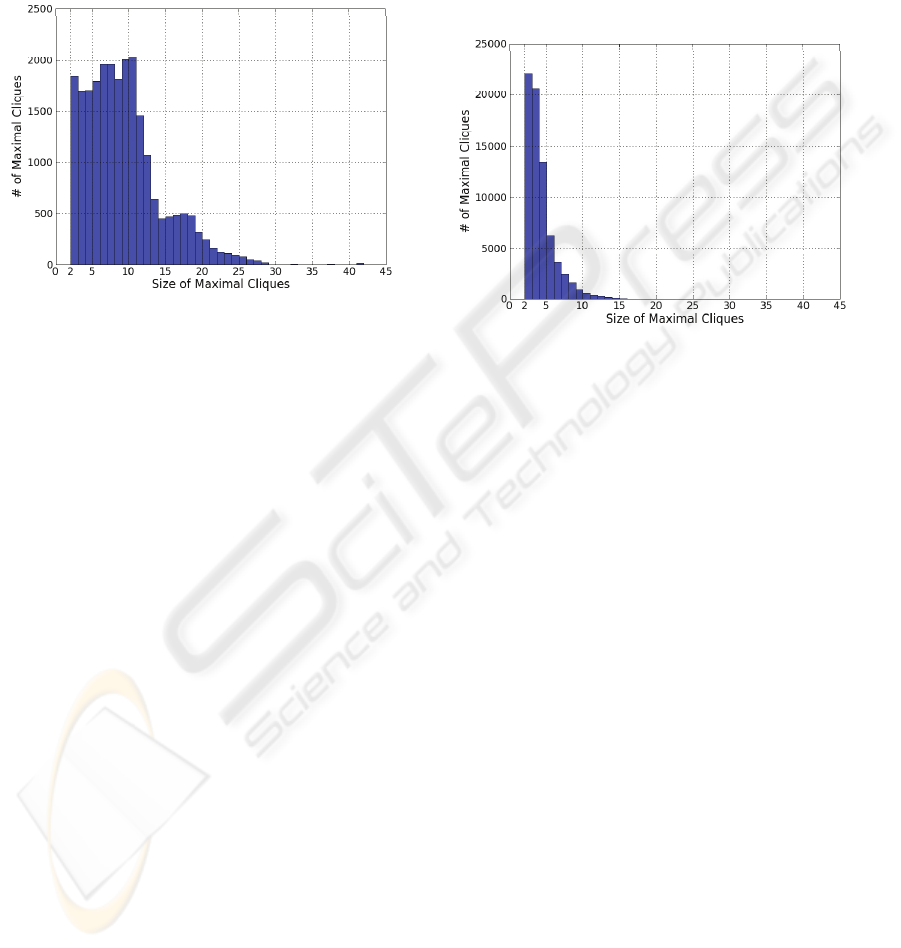

Figure 1: Cliques of different sizes in the graph of

coordinated nouns found in the Google n-grams corpus.

Cliques also indicate similarity within ontologies.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of maximal clique

sizes that we find when using the “Noun and Noun”

pattern in the Google n-grams to mine coordinated

pairs of capitalized terms. In general, the cliques

correspond to proper subsets of existing categories,

and mark out subsets whose members are more

similar to each other than to other members of the

larger category. For instance, we find this 11-clique:

{Environment, Education, Finance, Industry, Health,

Agriculture, Energy, Justice, Science, Defence, Transport}

This clique seems to cluster the key societal themes

around which governments typically structure

themselves, thus suggesting an ontological category

such as Government_Ministerial_Portfolio.

Since the notion of a clique is founded on a

social metaphor, an example concerning proper-

named entities can be illustrative. Using the Google

n-grams and a named-entity detector, we can build

an adjacency matrix of co-occurring entities and

derive from the resulting graph a set of maximal

cliques. One such clique is the following 4-clique:

{Steve_Jobs, Bill_Gates, Michael_Dell, Larry_Ellison}

In an ontology of proper-named entities, such as the

NameDropper ontology described in the next

section, we would expect these entities to all belong

to the category CEO. However, this category is

likely to have thousands of members, so many

additional sub-categories are needed to meaningfully

organize this space of CEOs. What makes these

particular CEOs interesting is that each is an iconic

founder of a popular technology company; thus, they

are more similar to each other than to CEOs of other

companies of comparable size, such as those of GE,

Wal-Mart or Pfizer. In the ideal ontology, one would

expect these entities to be prominent members of a

more specific category such as TechCompany-CEO.

Figure 2: Cliques of different sizes from the graph of

coordinated proper-names in the Google n-grams corpus.

As shown in Figure 2, large cliques (e.g., k > 10) are

less common in the graph of co-occurring proper-

named instances than they are in the graph of co-

occurring categories (Figure 1), while small cliques

are far more numerous, perhaps detrimentally so.

Consequently, we find many partially overlapping

cliques that should ideally belong to the same fine-

grained category, such as Irish-Author:

{Samuel_Beckett, James_Joyce, Oscar_Wilde, Jonathan_Swift}

{Samuel_Beckett, Bram_Stoker, Oscar_Wilde, Jonathan_Swift}

{Samuel_Beckett, Seamus_Heaney}

{Patrick_Kavanagh, Brendan_Behan, James_Joyce}

This fragmentation presents us with two possible

courses of action. We can merge overlapping cliques

to obtain fewer, but larger, cliques that are more

likely to correspond to distinct sub-categories. Or we

can apply clique analysis not at the level of category

instances, but at the level of categories themselves.

In this paper we shall explore the latter option.

In the next section we describe the creation of a

large ontology of proper-named entities with a fine-

grained category structure. These fine-grained

categories expose enough of their semantic structure

to permit analogical mapping between categories,

using a corpus-based approach described in section

4. This network of analogical mappings between

categories will then allow us to form cliques of

similar categories in section 5.

KEOD 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

36

3 NAMEDROPPER ONTOLOGY

As a test-bed for our explorations, we choose a

domain in which the notion of a clique has both

literal and metaphoric meaning. NameDropper is an

ontology of the proper-named concepts – such as

people, places, organizations and events – that one

would expect to find highlighted in an online

newspaper. NameDropper is used to semantically

annotate instances of these entity-kinds in news-

texts and to provide one or many analogically-linked

categorizations for each instance.

Categories in NameDropper are semantically-

rich, and serve as compressed propositions about the

instances they serve to organize. For instance, rather

than categorize Steve_Jobs as a CEO, we prefer to

categorize him as Apple_CEO or Pixar_CEO; rather

than categorize Linus_Torvalds as a developer, we

categorize him as a Linux_developer and a

Linux_inventor; and so on. In effect then, each

category is more than a simple generalization, but

also encodes a salient relationship between its

instances and other entities in the ontology (e.g.,

Linux, Apple, etc.). These categories use corpus-

derived intuitions to augment, rather than replace,

the rich categories offered by an online resource like

Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org). As we show in the

next section, this use of a rich-naming scheme for

categories also means that analogies between

different categories can be identified using simple

linguistic analysis of the structure of category labels.

The NameDropper ontology is extracted from

the text of the Google n-grams in a straightforward

manner. Simply, we use apposition patterns of the

following form to obtain category/instance pairs:

1. Mod Role Firstname Lastname

2. Mod1 Mod2 Role Firstname Lastname

3. Mod Role Firstname Midname Lastname

4. Mod1 Mod2 Role Firstname Midname Lastname

Here Mod, Mod1 or Mod2 is any adjective, noun or

proper-name, Firstname, Midname, and Lastname

are the appropriate elements of a named entity, and

Role is any noun that can denote a position,

occupation or role for a named-entity. A map of

allowable name elements is mined from WordNet

and Wikipedia, while a large list of allowable Role

nouns is extracted from WordNet by collecting all

single-term nouns categorized as Workers,

Professionals, Performers, Creators and Experts.

Since pattern (4) above can only be extracted from

6-grams, and Google provides 5-grams at most, we

use overlapping 5-grams as a basis for this pattern.

When applied to the Google n-grams corpus,

these patterns yield category/instance pairs such as:

a. Gladiator director Ridley Scott

b. Marvel Comics creator Stan Lee

c. JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald

d. Science Fiction author Philip K. Dick

Of course, not all pattern matches are viable

category/instance pairs. Importantly, the patterns

Mod Role or Mod1 Mod2 Role must actually

describe a valid category, so partial matches must be

carefully avoided. For instance, the following

matches are all rejected as invalid:

*e. Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy

*f. Vinci code author Dan Brown

*g. Meeting judge Ruth Bader Ginsberg

*h. The City star Sarah Jessica Parker

The n-grams in examples *e, *f and *h are clearly

truncated on the left, causing a necessary part of a

complex modifier to be omitted. In general this is a

vexing problem in working with isolated n-grams: it

is difficult to know if an n–gram stands alone as a

complete phrase, or if some key elements are

missing. In example *g we see that Meeting is not a

modifier for judge, but a verb that governs the whole

phrase. Nonetheless, we can deal with these

problems by performing the extraction and

validation of category labels prior to the extraction

of category/instance appositions. The following

patterns are thus used to extract a set of candidate

category labels from the Google n-grams:

5. the Mod Role

6. the Mod1 Mod2 Role

7. the Role of Mod1 Mod2 (

Æ

Mod1 Mod2 Role)

8. the Role of Mod (

Æ

Mod Role)

The patterns allow us to identify the strings the CEO

of Sun Microsystems (via 7) and the Supreme Court

judge (via 6) as yielding valid categories, but not the

Meeting judge or the Microsystems CEO (which are

not attested). Thus, only those collocations that can

be attested via patterns 5 – 8 in the Google n-grams

are allowable as categories in the patterns 1 – 4.

Overall, the intersection of patterns 1–4 and 5–8

extracts almost 60,000 different category/instance

pairings from the Google n-grams corpus, ascribing

an average of 2 categories each to 29,334 different

named-entity instances. Because the Google corpus

contains only those n-grams that occur 40 times or

more on the web, the extraction process yields

remarkably little noise. A random sampling of

NameDropper’s contents suggests that less than 1%

of categorizations are malformed.

ONTOLOGICAL CLIQUES - Analogy as an Organizing Principle in Ontology Construction

37

4 ANALOGICAL MAPPINGS

These patterns lead NameDropper to be populated

with many different complex categories and their

proper-named instances; each complex category,

like Apollo_11_astronaut, is a variation on a basic

role (e.g., astronaut) that serves to link an instance

(e.g., Neil_Armstrong) to this role in a specific

context (e.g., Apollo_11). There is some structure to

be had from these complex categories, since clearly,

an Apollo_11_astronaut is an Apollo_astronaut,

which in turn is an astronaut. But such structure is

limited, and as a result, NameDropper is populated

with a very broad forest of shallow and disconnected

mini-taxonomies. The ontology clearly needs an

upper-model that can tie these separate category

silos together, into a coherent whole. One can

imagine WordNet acting in this capacity, since the

root term of every mini-taxonomy is drawn from

WordNet’s noun taxonomy. Yet, while WordNet

provides connectivity between basic roles, it cannot

provide connectivity between complex categories.

For instance, we expect Apollo_astronaut and

Mercury_astronaut to be connected by the

observation that Apollo and Mercury are different

NASA programs (and different Greek Gods). As

such, Apollo_astronaut and Mercury_astronaut are

similar in a different way than Apollo_astronaut and

American_astronaut, and we want our ontology to

reflect this fact. Likewise, Dracula_author (the

category of Bram_Stoker) and Frankenstein_author

(the category of Mary_Shelley) are similar not just

because both denote a kind of author, but because

Dracula and Frankenstein are themselves similar. In

other words, the connections we seek between

complex categories are analogical in nature. Rather

than posit an ad-hoc category to cluster together

Dracula_author and Frankenstein_author, such as

Gothic_monster_novel_author (see Barsalou, 1983,

for a discussion of ad-hoc categories), we can use an

analogical mapping between them to form a cluster.

But as can be seen in these examples, analogy is

a knowledge-hungry process. To detect an analogy

between Apollo_astronaut and Mercury_astronaut, a

system must know that Apollo and

Mercury are

similar programmes, or similar gods. Likewise, a

system must know that Dracula and Frankenstein

are similar books to map Dracula_author to

Frankenstein_author. Rather than rely on WordNet

or a comparably large resource for this knowledge,

we describe here a lightweight corpus-based means

of finding analogies between complex categories.

Two complex categories may yield an analogy if

they elaborate the same basic role and iff their

contrasting modifier elements can be seen to belong

to the same semantic field. The patterns below give

a schematic view of the category mapping rules:

1. ModX_Role

Æ

ModY_Role

2. ModX_Mod_Role

Æ

ModY_Mod_Role

3. Mod_ModX_Role

Æ

Mod_ModX_Role

4. ModA_ModB_Role

Æ

ModX_ModY_Role

E.g., these rules can be instantiated as follows:

1. Java_creator

Æ

Perl_creator

2. Apple_inc._CEO

Æ

Disney_inc._CEO

3. Apollo_11_astronaut

Æ

Apollo_13_astronaut

4. Man_United_striker

Æ

Real_Madrid_striker

Clearly, the key problem here lies in determining

which modifier elements occupy the same semantic

field, making them interchangeable in an analogy.

We cannot rely on an external resource to indicate

that Java and Perl are both languages, or that Apple

and Disney are both companies. Indeed, even if such

knowledge was available, it would not indicate

whether a human would intuitively find Java an

acceptable mapping for Linux, say, or Apple an

acceptable mapping for Hollywood, say. What is an

acceptable level of semantic similarity between

terms before one can be replaced with another?

Fortunately, there is a simple means of acquiring

these insights automatically. As noted in section 2,

coordination patterns of the form Noun1 and Noun2

reflect human intuitions about terms that are

sufficiently similar to be clustered together in a list.

For instance, the following is a subset of the Google

3-grams that match the pattern “Java and *”:

Java and Bali Java and C++ Java and Eiffel

Java and Flash Java and Linux Java and Perl

Java and Python Java and SQL Java and Sun

Coordination typically provides a large pool of

mapping candidates for a given term. To minimize

noise, which is significant for such a simple pattern,

we look only for the coordination of capitalized

terms (as above) or plural terms (such as cats and

dogs). Much noise remains, but this does not prove

to be a problem since substitution of comparable

terms is always performed in the context of specific

categories. Thus, Perl is a valid replacement for

Java in the category Java_creator not just because

Java and Perl are coordinated terms in the Google 3-

grams, but because the resulting category,

Perl_creator, is a known category in NameDropper.

As a result, James_Gosling (Java_creator) and

Larry_Wall (Perl_creator) are analogically linked.

Likewise, Linux_creator and Eiffel_creator are valid

KEOD 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

38

analogies for Java_creator, but not Bali_creator or

Sun_creator, since these are not known categories.

Since categories can have multiword modifiers

(e.g., King_Kong_director, Harry_Potter_star), we

run a range of patterns on Google 3-,4- and 5-grams:

1. ModX and ModY

2. ModA ModB and ModX ModY

3. ModA ModB and ModX

4. ModX and ModA ModB

5. ModX and ModY PluralNoun

E.g., these patterns find the following equivalences:

1. Batman and Superman

2. James Bond and Austin Powers

3. Sin City and Gladiator

4. Microsoft and Sun Microsystems

5. Playboy and Penthouse magazines

These patterns show the scope for noise when

dealing with isolated n-grams. We might ask, what

makes the 4-gram Sin City and Gladiator a valid

coordination but the 3-gram City and Gladiator an

invalid one? Quite simply, the latter 3-gram does not

yield a pairing that can grounded in any pair of

complex categories, while the 4-gram yields the

analogies Sin_City_writer Æ Gladiator_writer,

Sin_City_director Æ Gladiator_director, and so on.

Likewise, the substitution Apples and Oranges is

not sensible for the category Apple_CEO because

the category Orange_CEO does not make sense.

To summarize then, the process of generating

inter-category analogies is both straightforward and

lightweight. No external knowledge is needed, e.g.,

to tell the system that Playboy and Penthouse are

both magazines of a somewhat sordid genre, or that

Batman and Superman are both comic-book

superheroes (interestingly, WordNet has entries for

all four of these words, but assigns them senses that

are utterly distinct from their pop-culture meanings).

Rather, we simply use coordination patterns to

formulate substitutability hypotheses in the context

of existing ontological categories. Thus, if a

substitution in one existing category yields another

existing category, then these two categories are held

to be connected by an analogy. We note that one

does not have to use Google n-grams to acquire

coordination patterns, but can use any corpus at all,

thereby tuning the analogical mappings to the

sensibilities of a given corpus/context/domain.

When applied to the complex categories of

NameDropper, using coordination patterns in the

Google n-grams, this approach generates 218,212

analogical mappings for 16,834 different categories,

with a mean of 12 analogical mappings per category.

5 ANALOGICAL CLIQUES

These analogical mappings provide a high degree of

pair-wise connectivity between the complex

categories of an ontology like NameDropper, or of

any ontology where category-labels are linguistically

complex and amenable to corpus analysis. This

connectivity serves to link instances in ways that

extend beyond their own categories. Returning to the

Playboy example, we see the following mappings:

Playboy_publisher

Æ

Penthouse_publisher

Playboy_publisher

Æ

Hustler_publisher

Hustler_publisher

Æ

Penthouse_publisher

All mappings are symmetric, so what we have here

is an analogical clique, that is, a complete sub-graph

of the overall graph of analogical mappings. Such

cliques allow us to generalize upon the pair-wise

connectivity offered by individual mappings, to

create tightly-knit clusters of mappings that can act

as generalizations for the categories involved. Thus,

the above mappings form the following clique:

{Playboy_publisher, Penthouse_publisher,

Hustler_publisher}

A corresponding clique of modifiers is also implied:

{Playboy, Penthouse, Hustler}

In turn, an analogical clique of categories also

implies a corresponding clique of their instances:

{Hugh_Hefner, Bob_Guccione, Larry_Flynt}

It is worth noting that this clique of individuals (who

are all linked in the public imagination) does not

actually occur in the cliques of proper-named

entities that we earlier extracted from the Google 5-

grams in section 2 (see Figure 2). In other words, the

analogical clique allows us to generalize beyond the

confines of the corpus, to create connections that are

implied but not always overtly present in the data.

The cohesiveness of an ontological category

finds apt expression in the social metaphor of a

clique. No element can be added to a clique unless

that new element is connected to all the members of

the clique. For instance, since Playboy magazine is a

rather tame example of its genre, we find it

coordinated with other, less questionable magazines

in the Google n-grams, such as Sports Illustrated,

Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone and Maxim magazines.

Thus, we also obtain mappings like the following:

Playboy_publisher

Æ

Rolling_Stone_publisher

ONTOLOGICAL CLIQUES - Analogy as an Organizing Principle in Ontology Construction

39

This, in turn, implies a correspondence of instances:

Hugh_Hefner

Æ

Jann_Wenner

All this is as one might expect, but note how the

association of Playboy and Rolling Stone does not

influence the structure of our earlier analogical

clique: Rolling_Stone_publisher does not join the

clique of Playboy_publisher, Penthouse_publisher

and Hustler_publisher because it lacks a connection

to the latter two categories; Jann_Wenner thus

avoids membership in the clique of Hugh_Hefner,

Bob_Guccione and Larry_Flynt.

Analogical cliques allow us to turn pair-wise

analogical mappings between categories into

cohesive superordinate categories in their own right.

Thus, {Playboy_publisher, Penthouse_publisher,

Hustler_publisher} acts as a super-ordinate for the

categories Playboy_publisher, Penthouse_publisher

and Hustler_publisher, and in turn serves as a

common category for Hugh_Hefner, Bob_Guccione

and Larry_Flynt. Because analogies are derived in a

relatively knowledge-lite manner from corpora,

these cliques act as proxies for the kind of explicit

categories that a human engineer might define and

name, such as publisher_of_men’s_magazines.

Analogical cliques can serve a useful structural role

in an ontology without being explicitly named in this

fashion, but they can also be extremely useful as part

of semi-automated knowledge-engineering solution.

In such a system, analogical cliques can be used to

find clusters of categories in an ontology for which

there is linguistic evidence – as mined from a corpus

– for a new super-ordinate category. Once identified

in this way, a human ontologist can decide to accept

the clique and give it a name, whereupon it is added

as a new first-class category to the ontology.

Recall from section 2 that mining the Google n-

grams for coordination among proper-named entities

yields a highly fragmented set of instance-level

cliques. In particular, Figure 2 revealed that

clustering instances based on their co-occurrence in

corpora produces a very large set of relatively small

cliques, rather than the smaller set of larger cliques

that one would expect from a sensible categorization

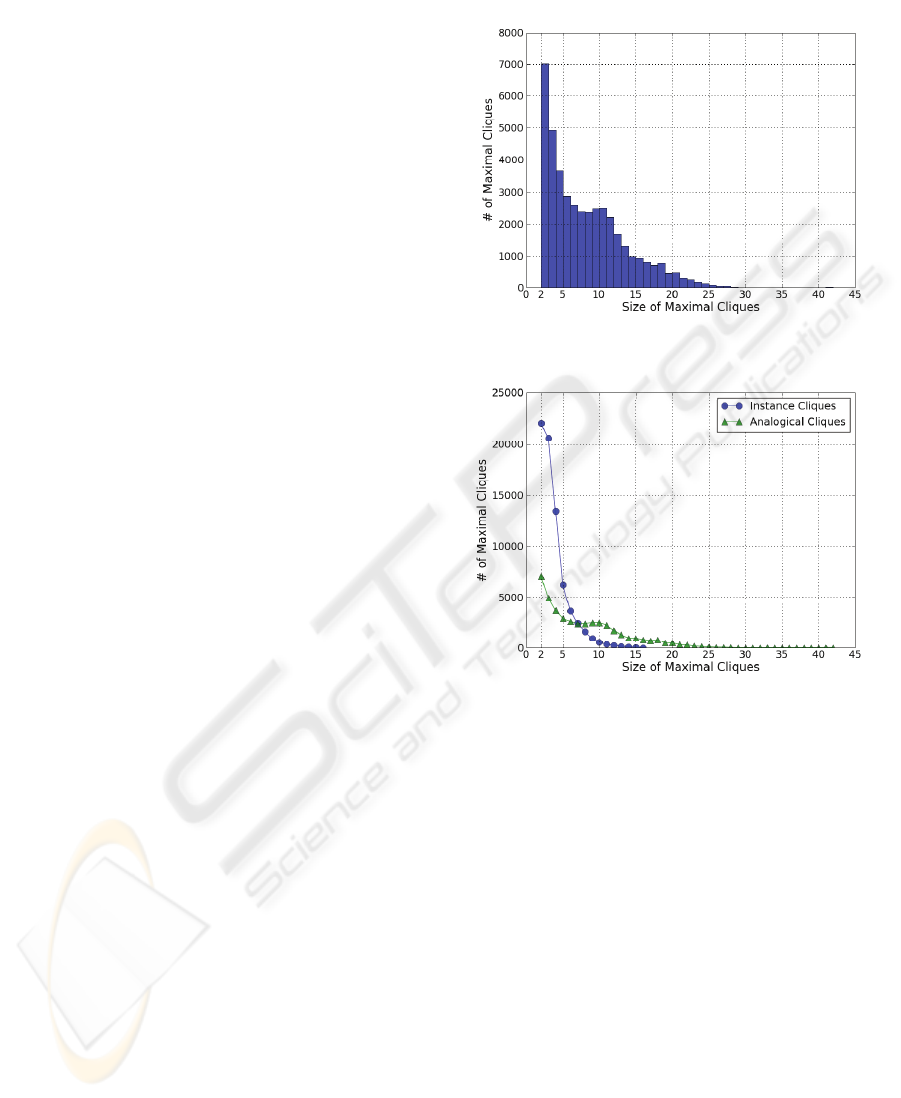

scheme. In contrast, Figure 3 below shows that the

graph of analogical mappings between categories

produces a wider distribution of clique sizes, and

produces many more maximal k-cliques of k > 10.

Figure 4 presents a side-by-side comparison of

the results of Figures 2 and 3. It shows that while the

analogical level produces less cliques overall

(42,340 analogical cliques versus 72,295 instance-

level cliques, to be specific), analogical cliques tend

to be larger in size, and thus achieve greater levels of

generalization than cliques derived from instances

directly.

Figure 3: Cliques of different sizes from the graph of

analogical mappings between NameDropper categories.

Figure 4: The distribution of instance-level clique sizes

(from coordinated proper-names) compared with the

distribution of analogical-clique sizes.

To appreciate the greater connectivity that a layer of

analogical cliques can provide to an ontology, we

must ask two important questions. What percentage

of the 72,295 instance-level cliques that are induced

from Google coordination patterns represent a

clustering of instances that all belong to one or more

of the same categories? In other words, what

percentage of instance-level cliques can be unified

under the same ontological category? Now, what

percentage of these cliques can be unified under the

same analogical clique? For the first question, the

answer is 33% – just 1 in 3 instance-level cliques are

proper subsets of a single ontological category. For

the second question, the answer is 56%. Clearly,

analogical cliques of categories offer a much better

model of the way that speakers intuitively cluster

their ideas in a text than do the categories alone.

KEOD 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

40

6 CONCLUSIONS

Word usage in context often defies our best attempts

to exhaustively enumerate all the possible senses of

a word (e.g., see Cruse, 1986). Though resources

like WordNet are generally very useful for language-

processing tasks, it is unreasonable to assume that

WordNet – or any print dictionary, for that matter –

offers a definitive solution to the problem of lexical

ambiguity. As we have seen here, the senses that

words acquire in specific contexts are sometimes at

great variance to the official senses that these words

have in dictionaries (Kilgarriff, 1997). It is thus

unwise to place too great a reliance on dictionaries

when acquiring ontological structures from corpora.

We have described here a lightweight approach

to the acquisition of ontological structure that uses

WordNet as little more than an inventory of nouns

and adjectives, rather than as an inventory of senses.

The insight at work here is not a new one: one can

ascertain the semantics of a term by the company it

keeps in a text, and if enough inter-locking patterns

are employed to minimize the risk of noise, real

knowledge about the use and meaning of words can

be acquired (Widdows and Dorow, 2002). Because

words are often used in senses that go beyond the

official inventories of dictionaries (e..g., recall our

examples of Playboy, Penthouse, Apollo, Mercury,

Sun and Apple), resources like WordNet can actually

be an impediment to achieving the kinds of semantic

generalizations demanded by a domain ontology.

A lightweight approach is workable only if other

constraints take the place of lexical semantics in

separating valuable ontological content from ill-

formed or meaningless noise. In this paper we have

discussed two such inter-locking constraints, in the

form of clique structures and analogical mappings.

Clique structures winnow out coincidences in the

data to focus only on patterns that have high internal

consistency. Likewise, analogical mappings enforce

a kind of internal symmetry on an ontology, biasing

a knowledge representation toward parallel

structures that recur in many different categories.

We have focused here on our own ontology,

NameDropper, created to annotate online newspaper

content. Our subsequent focus will expand to

include other, larger ontologies extracted from web-

content, including DBpedia and other Wikipedia-

derived resources (see Auer et al., 2007; Fu and

Weld, 2008). The category structure of Wikipedia is

sufficiently similar to that of NameDropper (in its

use of complex labels with internal linguistic

structure) that the analogical techniques described

here should be readily applicable. We shall see.

REFERENCES

Auer, S., Bizer, C., Lehmann, J., Kobilarov, G., Cyganiak,

R., Ives, Z., 2007. Dbpedia: A nucleus for a web of

open data. In Proc. of the 6

th

International Semantic

Web Conference, ISWC07.

Barsalou, L. W., 1983. Ad hoc categories. Memory and

Cognition, 11:211–227.

Brants, T., Franz, A., 2006. Web 1t 5-gram version 1.

Linguistic Data Consortium, Philadelphia.

Bron, C., Kerbosch, J., 1973. Algorithm 457: Finding all

cliques of an undirected graph. Communications of the

ACM 16(9). ACM press, New York.

Budanitsky, A., Hirst, G., 2006. Evaluating WordNet-

based Measures of Lexical Semantic Relatedness.

Computational Linguistics, 32(1):13-47.

Croitoru, M., Hu, B., Srinandan, D., Lewis, P., Dupplaw,

D., Xiao, L., 2007. A Conceptual Graph-based

Approach to Ontology Similarity Measure. In Proc. Of

the 15

th

International Conference On Conceptual

Structures, ICCS 2007, Sheffield, UK.

Cruse, D. A., 1986. Lexical Semantics. Cambridge, UK”

Cambridge University Press.

De Leenheer, P., de Moor, A., 2005. Context-driven

Disambiguation in Ontology Elicitation. In Shvaiko P.

& Euzenat J. (eds.), Context and Ontologies: Theory,

Practice and Applications, AAAI Technical Report

WS-05-01:17–24. AAAI Press.

Dong, Z., Dong, Q., 2006. HowNet and the Computation

of Meaning. World Scientific. Singapore.

Euzenat, J., Shvaiko, P., 2007. Ontology Matching.

Springer Verlag. Heidelberg.

Falkenhainer, B., Forbus, K., Gentner, D., 1989. Structure-

Mapping Engine: Algorithm and Examples. Artificial

Intelligence, 41:1-63

Fellbaum, C., (ed.). 1998. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical

Database. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Gruber, T., 1993. A translation approach to portable

ontologies. Knowledge Acquisition, 5(2):199-220.

Guarino, N., (ed.) 1998. Formal Ontology and Information

Systems. Amsterdam: IOS Press. Proceedings of

FOIS1998, June 6-8, Trento, Italy.

Hearst, M., 1992. Automatic acquisition of hyponyms

from large text corpora. Proc. of the 14

th

International

Conference on Computational Linguistics, pp 539–

545.

Kilgarriff, A., 1997. I don’t believe in word senses.

Computers and the Humanities, 31(2), 91-113.

Veale, T., Li, G., Hao, Y., 2009. Growing Finely-

Discriminating Taxonomies from Seeds of Varying

Quality and Size. In Proc. of EACL 2009, Athens.

Widdows, D., Dorow, B., 2002. A graph model for

unsupervised lexical acquisition. In Proc. of the 19

th

Int. Conference on Computational Linguistics.

Wu, F., Weld, D. S., 2008. Automatically Refining the

Wikipedia Infobox Ontology. In Proc. of the 17

th

World Wide Web Conference, WWW 2008.

ONTOLOGICAL CLIQUES - Analogy as an Organizing Principle in Ontology Construction

41