VALUE KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Process Structuring for Multi-party Conflict

John Rohrbaugh and Shahidul Hassan

Rockefeller College of Public Affairs, University at Albany, SUNY, 1400 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12202, U.S.A.

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Values, Judgment Analysis, Resource Allocation, Analytical Mediation.

Abstract: Value knowledge management (VKM) comprises the process structuring required to make individual and/or

group values explicit in a manner so that such initially tacit knowledge appropriately informs decision

making. This paper presents a case in which VKM is used for structuring an organizational preparation

process for a new and substantial initiative. Fundamental group conflicts exist with respect to this initiative

and, more immediately, with respect to the extent of preparation envisioned. The relative importance of two

key values is at issue: increasing human capital and reducing project costs. The case illustrates a three-stage

approach to VKM and demonstrates how the articulation of group judgment policies, the development of a

shared resource allocation model, and the application of analytical mediation can make a substantial

contribution to organizational problem solving or opportunity seeking.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the field of knowledge management (KM), the

distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge has

remained an important touchstone (Liyanage, Elhag,

Ballal, & Li, 2009). While explicit knowledge has

been articulated, codified, and communicated

already in some symbolic form, tacit knowledge,

though perhaps equivalent in its coherence and

correspondence (Hammond, 1996), remains as yet

implicit and unexpressed. Tacit knowledge must be

inferred by others over time as actions are observed.

Both individuals and groups are viewed as

possessing tacit knowledge; some have argued that

organizations also can be considered to be

repositories of tacit, as well as explicit, knowledge

(Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 2003).

One of the most important domains of tacit

knowledge pertains to values, that is, personal

values, group values, and organizational values.

According to Scott (1965), a value is a standard

which influences—in full or in part—commitment to

preferred actions and goals (i.e., what ought to be

accomplished or what ought to be achieved). When

one value alone fully explains commitment to an

action or goal (e.g., the standard for preserving all

human life or for speaking only the truth), this value

is absolute. In most situations, however, two or

more relative or competing values differentially

influence such commitments.

Surprisingly, value knowledge is not identified

as a type (e.g., declarative, procedural, causal,

conditional, relational, or pragmatic) in knowledge

taxonomies (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Value

knowledge management (VKM), a proposed domain

for KM introduced in the present paper, is absolutely

central to any explication of organizational problem

solving or opportunity seeking. VKM comprises the

process structuring required to make individual

and/or group values explicit in a manner so that such

initially tacit knowledge appropriately informs

decision making and provides necessary

retraceability and sufficient accountability. Without

VKM, an organization is unable to maintain its

intentional course because it lacks capacity either to

articulate or to exercise its priorities.

Values cannot be articulated meaningfully in the

abstract, of course, and any general statement of

their relative importance is useless (Keeney, 1992,

147-148). Therefore, the foundation of VKM is the

assumption that the most informative expression of

individual and group values always will be in

reference to specific and well-understood situations.

The management of value knowledge must originate

in particular circumstances that can elicit statements

of preference. Since values are the standards which

influence commitment to preferred actions and

63

Rohrbaugh J. and Hassan S. (2009).

VALUE KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT - Process Structuring for Multi-party Conflict.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, pages 63-68

Copyright

c

SciTePress

goals, the clearest insight into their relative

importance—if trade-offs are induced at all—

emerges where they are ―put to the test.‖

The present paper presents a case in which VKM

is used to structure an organizational preparation

process for a new and substantial initiative.

Fundamental group conflicts exist with respect to

this initiative and, more immediately, with respect to

the extent of preparation envisioned. The relative

importance of two key values is at issue: increasing

human capital and reducing project costs. In turn,

these two values influence the level of individual

and group commitment to five preferred

organizational actions: process planning, process

scope, process staffing, trainer skill, and suitability

of facilities. In this case, VKM entails a sequence of

three stages: the articulation of group judgment

policies, the development of a shared resource

allocation model, and the application of analytical

mediation.

2 GROUP JUDGMENT POLICIES

One of the most well-tested and applied methods for

measuring individual and group commitment to

preferred actions and goals is through the use of

judgment analysis (Cooksey, 1996; Rohrbaugh,

2001). Sometimes identified as ―policy capturing,‖

judgment analysis typically involves the presentation

of a series of realistic cases, scenarios, or vignettes

that systematically differ on several well-specified

dimensions. By regressing numerical judgments that

are expressed in response to variations in these

dimensions, an explicit model of the judgment

process can be inferred that algebraically

represents—and can predict—the assessments made

in a judgment process.

In the present case, five dimensions of

organizational action are contemplated: process

planning, process scope, process staffing, trainer

skill, and suitability of facilities. The judgment to be

made is the extent to which these dimensions

influence increases in human capital of relevance to

the new and substantial initiative.

i

Three groups—

teams from human resources management (HRM),

budget and finance (B&F), and new project

coordination (NPC)—with long-standing conflicts of

value within the organization independently meet in

a brief session to articulate their respective judgment

policies.

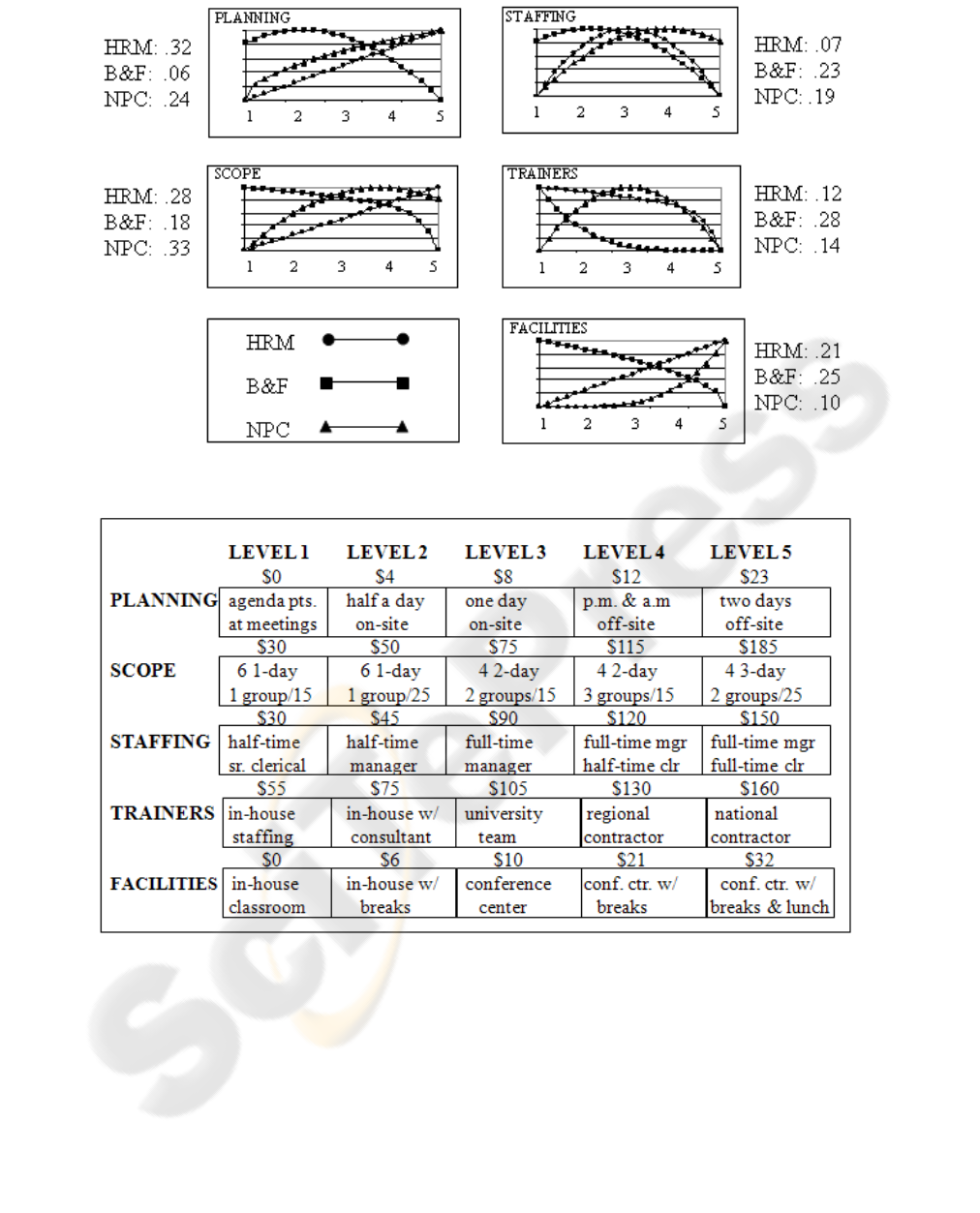

The initial series of 35 hypothetical scenarios

presented to each group for consideration is

illustrated by three cases shown in Figure 1; a full

description of the method is beyond the scope of this

paper (see Reagan-Cirincione, 1994). The relative

weights and function forms that the three groups

produce for the five dimensions of organizational

action are displayed in Figure 2. Note, for example,

that HRM places the greatest relative weight on

planning, which is least important to B&F. Both

function forms for the dimension of facilities are

positive for HRM and NPC; B&F, however,

generates a negative function form. Even in this first

stage of VKM, these three sets of relative weights

and function forms make explicit the nature of the

organizational conflict that exists between the three

groups.

Case 1

Planning Level 3: one-day meeting on-site

Scope Level 2: 25 participants; 6 one-day

sessions

Staffing Level 3: full-time manager

Trainer Level 4: regional contractor

Facilities Level 1: in-house space

Case 2

Planning Level 5: two-day meeting off-site

Scope Level 3: 15 participants; 4 two-day

sessions

Staffing Level 2: half-time manager

Trainer Level 4: regional contractor

Facilities Level 3: conference center

Case 3

Planning Level 3: one-day meeting on-site

Scope Level 1: 15 participants; 6 one-day

sessions

Staffing Level 1: half-time senior clerical

Trainer Level 2: in-house staff with

consultant

Facilities Level 2: in-house space with

catering

Figure 1: Examples of three scenarios presented for group

judgments.

3 SHARED RESOURCE

ALLOCATION MODEL

A resource allocation model identifies the full set of

activities, projects, or programs vying for support, as

well as the multiple levels at which investments

could be made in each. A full description of the

method for constructing resource allocation models

with groups is also beyond the scope of this paper

(see, for example, Adelman, 1984; Carper &

Bresnick, 1989; Phillips, 1985, Schuman &

Rohrbaugh, 1991, Vari & Vecsenyi, 1992). The

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

64

Figure 2: Relative weights and function forms for three groups.

Figure 3: Joint resource allocation structure with costs (in thousands).

shared resource allocation model for the present case

is presented in Figure 3. Five levels of resource

investments are being considered for each

organizational action; levels are listed from left to

right across the rows in order of their increasing costs

as the B&F team estimates.

ii

The five ―Level 1‖ allocations for planning, scope,

staffing, trainers, and facilities would cost $115,000

altogether; the five ―Level 5‖ allocations would cost

an additional $435,000 or $550,000 altogether. From

the entirely lowest to the entirely highest resource

allocations, there are 3,125 possible combinations of

investment levels (i.e., 5 x 5 x 5 x 5 x 5). If all three

groups shared the absolute value of reducing project

costs, there would be no conflict with respect to the

extent of preparation envisioned. Planning would be

conducted as agenda points for currently scheduled

meetings. The scope of preparation would involve

VALUE KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT - Process Structuring for Multi-party Conflict

65

one group of participants in a series of six one-day

sessions. Staffing would be provided by the

commitment of a senior clerical employee on half-

time assignment. Trainers would be selected from

current staff members. One of the regular meeting

rooms in the central office would be reserved for

instructional space; no food or beverages would be

provided. These are all ―Level 1‖ allocations that

minimize project costs.

The introduction of a second and competing

value—increasing human capital—leads to the trade-

offs being considered here. In an organizational

preparation process for a new and substantial

initiative, enhancement of human capital is achieved

with the expenditure of ever greater monetary

amounts. The three teams from human resources

management (HRM), budget and finance (B&F), and

new project coordination (NPC) somewhat uniquely

consider the relative importance of cost containment

and human capital expansion. In this case, the

application of VKM is critical to locating a specific

proposal, expressed as one particular combination of

investment levels out of the 3,125 possible, to which

the three groups will agree and make a genuine

commitment.

4 APPLICATION OF

ANALYTICAL MEDIATION

Analytical mediation is a computer-supported process

used in conflictual situations to identify potential

settlements with high joint benefits (Mumpower,

Schuman, & Zumbolo, 1988). Integer goal

programming provides a means for readily

identifying settlements that lie on or near the efficient

frontier. The basic objective for the application of

analytical mediation is not to prescribe a specific

settlement but, rather, in the spirit of the single-

negotiating text idea proposed by Raiffa (1982), to

provide a concrete, externally authored proposal

which the negotiating teams can criticize and use as a

springboard for developing a settlement that might be

considered as even more mutually satisfactory.

The use of analytical mediation for VKM in this

case follows closely the method described by

Mumpower and Rohrbaugh (1996) and extended to

multi-party resource allocation by Darling,

Mumpower, Rohrbaugh, and Vari (1999). As

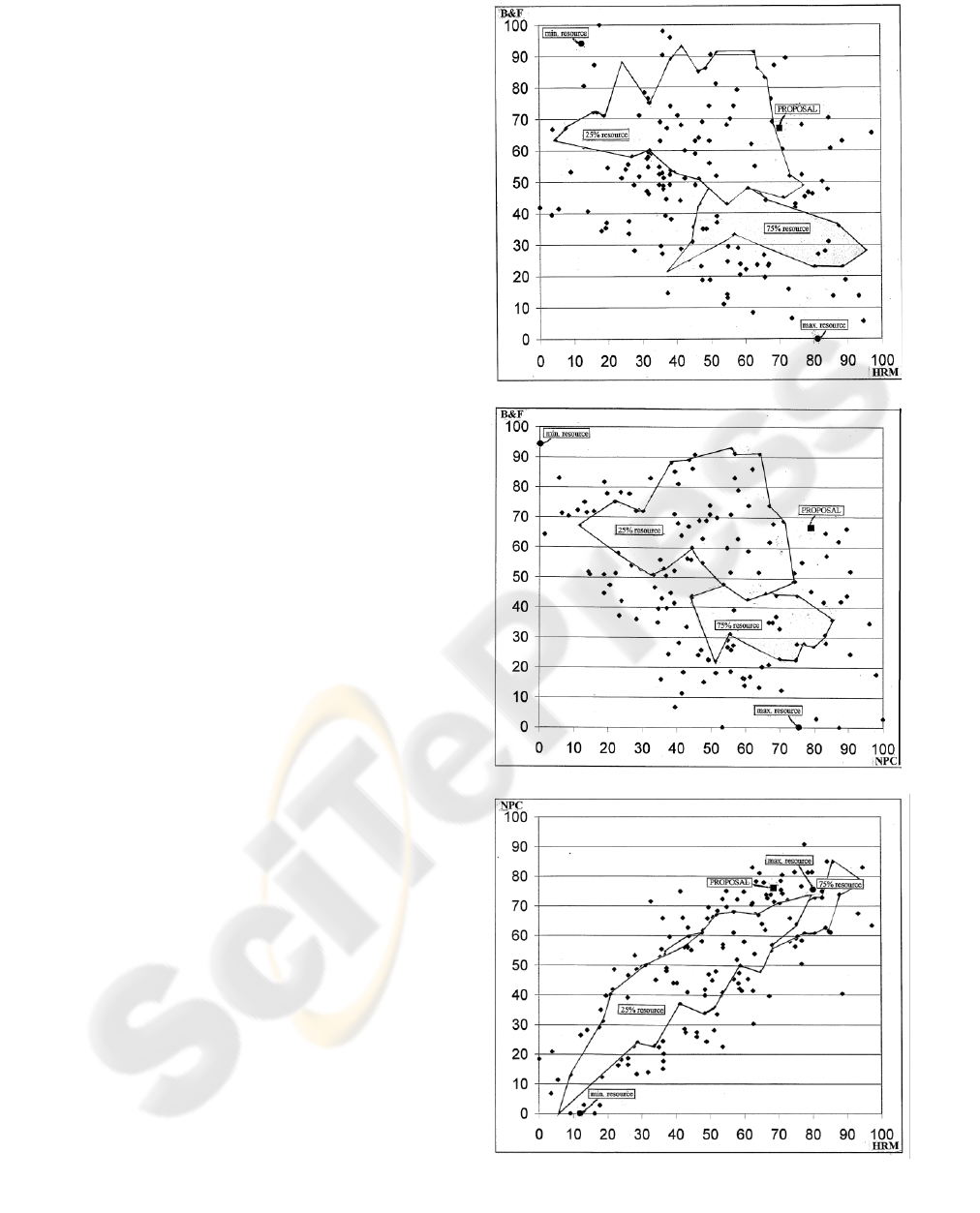

illustrated in Figure 4, all possible settlements are

arrayed in the joint utility space for each pair of

teams. If a pair of teams share a similar commitment

to preferred actions and goals, the points that are

plotted appear around the diagonal from the lower left

Figure 4: An illustration of analytical mediation.

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

66

to the upper right (as shown for HRM and NPC). If a

pair of teams differ in their commitment to preferred

actions and goals due to opposing values, the points

that are plotted appear around the diagonal from the

upper left to the lower right (as shown for B&F and

HRM, also for B&F and NPC).

Highlighted in Figure 4 are two regions

containing 1) all settlements carrying a cost that is

25% of the total increased cost from minimum to

maximum; and 2) all settlements carrying a cost that

is 75% of the total increased cost from minimum to

maximum. Many more such regions could be defined.

Also identified are the points of minimum cost (all

―Level 1‖ allocations) and of maximum cost (all

―Level 5‖ allocations). The degree of overlap in the

two regions—clearly visible for all three pairs of

teams—indicates that considerable joint utility can be

achieved without incurring large costs. In other

words, the organization does not need to expend

upwards to 75% of the total increased cost for the

three groups to agree and make a genuine

commitment to a shared organization preparation

process; in fact, increased cost reduces the utility of

settlements for the B&F group.

One proposed settlement identified in Figure 4

stands out in these graphs:

Planning Level 4: afternoon and following

morning meeting off-site ($12,000)

Scope Level 4: Three groups of 15 participants;

four two-day sessions ($115,000)

Staffing Level 3: full-time manager ($90,000)

Trainer Level 2: in-house staff with

consultant support ($75,000)

Facilities Level 2: in-house space with light food

and beverages during breaks ($6,000)

At a total cost of under $300,000 (that is, about

40% of the total increased cost from minimum to

maximum), this proposal provides between two-thirds

and three-quarters of the total utility that would be

gained by each group had their own ―ideal‖ plan of

action been adopted.

iii

On a utility scale from 0 to

100, this proposal provides the HRM group with 69,

the B&F group with 67, and the NPC group with 77.

Movement away from this proposal to other possible

settlements appears to advantage one or two teams

more greatly at the disadvantage of the other(s) but

certainly is deserving of the groups’ consideration.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

The present case—a decision about the allocation of

resources to an organizational preparation process for

a new and substantial initiative—offers a prime

example of the importance of value knowledge

management (VKM). Although value knowledge is

an under-represented domain of study in the KM

field, the effective articulation, codification, and

communication of individual and group values

remain highly consequential aspects of any

organizational problem-solving or opportunity-

seeking process. Since values, whether relative or

absolute, are the standards which influence

commitment to preferred actions and goals, an

organization maintains its intentional course by acting

in a value-coherent and value-correspondent manner

(Hammond, 1996).

Many organizational conflicts have integrative

potential, that is, where the nature of the problem

permits solutions that are better than zero-sum for all

parties (Walton & McKersie, 1968); in such

situations, each party can gain reasonably well and

not necessarily at the expense of the others. Of

course, the nature of the favorable ―solution space‖ as

depicted in Figure 4 would not be known without the

application of VKM. In fact, the relative values of

the three teams—HRM, B&F, and NPC—that

undergird the plotting of joint utilities would not have

been evoked explicitly without the use of the

judgment analysis method in the initial VKM stage.

Even in organizational circumstances in which a

single team is called upon to allocate resources, the

challenge is made difficult because of the number of

activities, projects, or programs that request (or

require) support. Furthermore, experienced

professionals realize that resource allocations rarely

should be simplified as dichotomous choices (i.e., ―go

or no-go‖ choices between full investment versus

non-investment); intermediate levels of resource

commitment almost always exist and should be

considered. In the present resource allocation model

with merely five organizational actions being

considered at only five levels of investment, the total

number of alternative combinations exceeds 3,000, a

highly complex task that increases geometrically with

more actions and/or more levels.

When resource allocation decisions are shared by

multiple groups bringing their own respective values

to the process, the complexity of the task is made

even greater. VKM provides an extraordinarily

valuable approach for process structuring in multi-

party conflict. The present trade-off between two key

values—increasing human capital and reducing

project costs—is considered from the unique

perspective of each of the three teams. At a total cost

of under $300,000 (that is, about 40% of the total

increased cost from minimum to maximum), the

proposal described in this case provides between two-

VALUE KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT - Process Structuring for Multi-party Conflict

67

thirds and three-quarters of the total utility that would

be gained by each group had their own ―ideal‖ plan of

action been adopted. Arguably, without VKM

substantial joint project gains and/or resource savings

might be forfeited.

In conclusion, the importance of knowledge about

individual and group values, as well as the

management of such knowledge, should be an

increasingly important domain of study within the

KM field. This is especially true where the

development of lateral relations and knowledge

sharing across professional subgroups is of

organizational interest (Rangachari, 2009; van der

Spek, Kruizinga, & Kleijsen, 2009). The present case

illustrates one approach to VKM and demonstrates

how the articulation of group judgment policies, the

development of a shared resource allocation model,

and the application of analytical mediation make a

substantial contribution to organizational problem

solving or opportunity seeking. The further

development of VKM and the possibility of more

frequent VKM applications should follow.

REFERENCES

Adelman, L., 1984. Real-time computer support for

decision analysis in a group setting: Another class of

decision support systems. Interfaces, 14, 75-83.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E., 2001. Knowledge management

and knowledge management systems: Conceptual

foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25,

107-136.

Carper, W. B., & Bresnick, 1981. Strategic planning

conferences. Business Horizons, 32, 34-40.

Cooksey, R. W., 1996. Judgment analysis: Theory,

methods, and applications. New York: Academic.

Darling, T. A., Mumpower, J. L., Rohrbaugh, J., & Vari,

A., 1999. Negotiation support for multi-party resource

allocation: Developing recommendations for decreasing

transportation-related air pollution in Budapest. Group

Decision and Negotiation, 8, 51-75.

Easterby-Smith, M., & Lyles, M. A., 2003. The Blackwell

handbook of organizational learning and knowledge

management. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hammond, K. R., 1996. Human judgment and social

policy: Irreducible uncertainy, inevitable error,

unavoidable injustice. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Keeney, R. L., 1992. Value-focused thinking: A path to

creative decision making. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Liyanage, C., Elhag, T. Ballal, T., & Li, Q., 2009.

Knowledge communication and translation – a

knowledge transfer model. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 13, 118-131.

Mumpower, J. L., & Rohrbaugh, J., 1996. Negotiation and

design: Supporting resource allocation decisions

through analytical mediation. Group Decision and

Negotiation, 5, 385-409.

Mumpower, J. L., Schuman, S. P., & Zumbolo, A., 1988.

Analytical mediation: An application in collective

bargaining. In R. M. Lee, A. M. McCosh, & P.

Migliarese (Eds.), Organisational Decision Support

Systems. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Phillips, L. D., 1985. Systems for solutions. Datamation

Business, (April), 26-29.

Rangachari, P., 2009. Knowledge sharing networks in

professional complex systems. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 13, 132-145.

Reagan-Cirincione, P., 1994. Improving the accuracy of

group judgment: A process intervention combining

group facilitation, social judgment analysis, and

information technology. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes, 58, 246-270.

Rohrbaugh, J., 2001 The relationship between strategy and

achievement as the basic unit of group functioning. In

K. R. Hammond & T. R. Stewart (Eds.), The Essential

Brunswik: Beginnings, Explications, Applications.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Schuman, S. P., & Rohrbaugh, J., 1991. Decision

conferencing for systems planning. Information and

Management, 21, 147-159.

Scott, W. A., 1965. Values and organizations. Chicago:

Rand McNally.

van der Spek, R., Kruizinga, E., & Kleijsen, A., 2009.

Strengthening lateral relations in organisations through

knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 13, 3-12.

Vari, A., & Vecsenyi, J., 1992. Experiences with decision

conferencing in Hungary. Interfaces, 22, 72-83.

Walton, R. E., & McKersie, R. B., 1965. A behavioral

theory of labor negotiations. New York: McGraw-

Hill.

_________________________

i

Reductions in project costs are considered in the next

section.

ii

In cases where teams disagree on cost projections,

additional meetings to achieve consensus may be

required. The use of ―sensitivity analyses‖ can support

such meetings by identifying which differences have

little or no consequence on outcomes.

iii

For HRM, the ideal would be levels 5, 5, 3, 1, and 5,

respectively, at a cost of $385,000. For B&F, the ideal

would be levels 2, 1, 2, 1, and 1, respectively, at a cost

of $134,000. For NPC, the ideal would be levels 5, 4, 4,

3, and 5, respectively, at a cost of $395,000. These

levels can be identified directly from Figure 2 as the

maximum points on each group’s set of function forms.

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

68