AN AGENT BASED SIMULATION OF THE DYNAMICS

IN COGNITIVE DEPRESSOGENIC THOUGHT

Azizi Ab Aziz and Michel C. A. Klein

Agent Systems Research Group, Department of Artificial Intelligence, Faculty of Sciences

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1081, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Keywords: Agent based Simulation, Affective Disorder, Cognitive Depressogenic Formation, Social Support

Feedbacks.

Abstract: Depression is a common mental disorder. Appropriate support from others can reduce the cognitive

distortion that can be caused by subsequent depressions. To increase our understanding of this process, an

agent model is presented in this paper in which the positive and negative effects of social support and its

relation with cognitive thoughts are modelled. Simulations show the effect of social support on different

personality types. A mathematical analysis of the stable situations in the model gives an additional

explanation of extreme cases. Finally, a formal verification of expected relations between support, risk

factors and depressive thoughts is performed on the simulation traces to check whether the simulations

describe realistic processes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cognitive vulnerability is one of the main concepts

that play an important role to escalate the risk of

relapse in affective disorder (depression). In a

broader spectrum, it is a defect belief, or structures

that are persistently related for later emergent in

psychological problems. Before further reviewing

the underlying concepts of the vulnerability, it is

essential to understand its connection between

relapse condition in unipolar depression and social

support (Aziz et al., 2009). Unipolar depression is a

mental disorder, distinguished by a persistent low

mood and loss of awareness in usual activities

(Beck, 1987). Normally, under a certain degree of

stressors exposure, an individual with a history of

depression will develop a negative cognitive content

(thought), associated with the past losses. Such

cognitive content is often related to the maladaptive

schemas, which in a long run will cause individual’s

ongoing thought capability to be distorted and later

to be dysfunctional (Robinson and Alloy, 2003).

However, this cognitive distortion can be reduced

through appropriate supports from other members

within the social support network (Heller and Rook,

1997). Social support network is made up of friends,

family and peers. Some of it might be professionals

and support individuals in very specific ways, or

other people in this network might be acquaintances

in contact with every day. It has been suggested that

social support naturally can help to prevent and

decrease stress through positive inferences, which

later curbs the formation of cognitive vulnerability

(Alloy et al., 2004). However, some literatures have

shown that certain supports provide contrast effects.

Rather than attenuating the negative effects from

stressors, it will eventually amplify the individual’s

condition to get worse (Coyne, 1990).

In this paper, these positive and negative effects

from social support interaction and its relation with

cognitive thought are explored. To fulfil this

requirement, a dynamic model about cognitive

depressogenic thought is proposed. The proposed

model can be used to approximate a human’s

cognitive depressogenic thought progression

throughout time. This paper is organized as follows.

The first section introduces main concepts and

existing theory of cognitive depressogenic thought

and hopelessness. Thereafter, a formal model is

described and simulated (Section 3 and 4). The

model has been verified by a mathematical analysis

(Section 5) and by checking properties of simulation

traces (Section 6). Finally, Section 7 summarizes the

paper with a discussion and future work for this

model.

232

Ab Aziz A. and C. A. Klein M. (2010).

AN AGENT BASED SIMULATION OF THE DYNAMICS IN COGNITIVE DEPRESSOGENIC THOUGHT .

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence - Agents, pages 232-237

DOI: 10.5220/0002736102320237

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 FUNDAMENTALS IN

COGNITIVE DEPRESSOGENIC

THOUGHT

People vary in their abilities to overcome stressful

life events and it allows them to manage their

troubles and not be overwhelmed. These variations

answer why the level of severity and duration among

different individuals can be diverse in nature. To

explain this mechanism, the Extended Hopelessness

Theory of Depression is used. In this theory, people

who exhibit a negative inferential style, in which

they describe, attribute negative events to stable

(likely to persist over time) and global (likely to

affect many aspects of life) will most likely to infer

themselves as fundamentally useless and flawed

(Abramson et al. 1999).

Although it is well documented that social support

mitigates a risk of relapse, but there is a condition

where feedbacks from the social support members

may indirectly escalate the risk of relapse. Such

feedbacks are considered as “maladaptive inferential

feedback” (MIF), and normally increase the negative

thought formation (Alloy et al., 2004). Contrary to

this, an adaptive inferential feedback (AIF) provides

a buffer to reduce the threat, by countering negative

inferences for negative event. AIF asserts that when

a social support member offers comfort by

attributing the source of negative event to be

unstable, it will later diminish the risk of creating

maladaptive inferences (Dobkin et al. 2004).

In addition, the Extended Hopelessness Theory

of Depression relates the development cognitive

depressogenic thought through previously described

two precursors. First, the present of positive social

support feedback (AIF) acts as a buffer to decrease

individuals’ possibility of having cognitive

depressogenic thought over time. Second,

individuals with cognitive depressogenic thought

will make negative inferences when facing negative

events. This condition is also associated with less

AIF from the social support members. Moreover,

both of these conditions capable to predict changes

in stressful events. Therefore, it can be further used

to elaborate the immunity level of individuals (as

contrast in vulnerability concept). In addition, many

studies have also associated the lower risk of

depression with the presence of AIF (Coyne, 1990).

As indicated in several previous works,

inferential feedbacks provide one of the substantial

factors towards the development of cognitive

depressogenic thought over time. By combining

either one of these two factors together with

situational cues, it leads to the formation of either

cognitive depressogenic inference or positive

attributional style. Situational cues refers to a

concept that explains individuals’ perception that

highly influenced by cues from events

(environment). Individuals under the influence of

negative thought about themselves will tend to

reflect these negative cognitions in response to the

occurrence of stressors. These later develop the

conditions called “stress-reactive rumination” and

“maladaptive inference” (Spasojevic and Alloy,

2001).

Stress reactive rumination reflects a condition

where individuals have difficulty in accessing

positive information, and further develop a negative

bias towards inference (maladaptive inference). This

process is amplified by previous exposures towards

cognitive depressogenic thought episode. After a

certain period, both conditions are related to the

formation of hopelessness. Hopelessness is defined

by the expectation that desired outcome will not

occur, or there is nothing one can do to make it right

(Panzarella et al. 2006). Prolong and previous

exposure from hopelessness will lead to the

development of cognitive depressogenic thought.

However, this condition can be reduced by having a

positive attributional style, which normally existed

during the presence of AIF and low situational cues

perception (Crossfield et al. 2002).

In short, the following relations can be identified

from the literature: (1) prolong exposure towards

MIF, negative events, and high-situational cues can

lead to the development of cognitive depressogenic

thought. (2) a proper support (AIF) will reduce the

risk of further development of future cognitive

depressogenic thought. (3) Individuals with high

situational cues and proper support will be less

effective in reducing the progression of cognitive

depressogenic thought, compared to the individuals

with less situational cues.

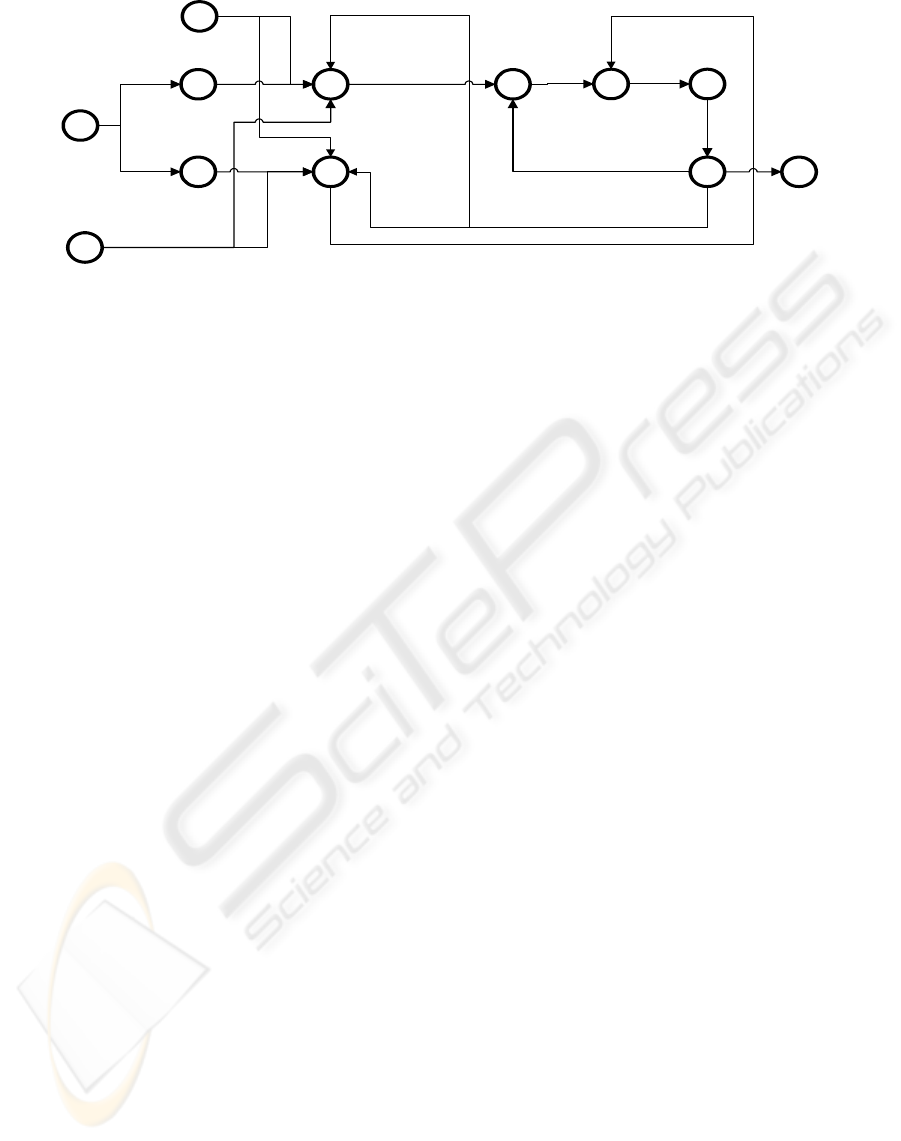

3 FORMAL MODEL

This section discusses the details of the dynamic

model. In this model, three major components

namely; environment, inferential feedbacks, and

thought formation will represent the dynamic of

interactions between social support feedback and

individuals involved in negative thought formation

during the beginning of relapse and recurrence in

depression. In the formalization, those important

concepts are translated into several interconnected

nodes. These nodes are designed in a way to have

values ranging from 0 (low) to 1 (high). Figure 1

AN AGENT BASED SIMULATION OF THE DYNAMICS IN COGNITIVE DEPRESSOGENIC THOUGHT

233

depicts the global interaction between these nodes.

3.1 Temporal Specification

In order to develop a model, a temporal specification

language called LEADSTO and its supporting

software environment has been used. LEADSTO

enables one to model direct temporal relationship

between two state properties (dynamic properties).

Consider the format of α→→

e,f,g,h

β, where α and β

are state properties in form of a conjunction of atoms

(conjunction of literals) or negations of atoms, and

e,f,g,h represents non-negative real numbers. This

format can be interpreted as follows;

If state α holds for a certain time interval with

duration g, after some delay (between e and f),

state property β will hold a certain time interval of

length h.

For a more detailed discussion of this language, see

(Bosse et al., 2007). To formalize the concepts of

properties on dynamics relationship introduced in

the previous section (Section 2), for each of them, a

logical atom using predicate calculus is introduced.

To formalize the dynamic relationship between these

concepts, the following temporal relationships are

used.

NEVT: Negative Events

A set of generated events is experienced by an agent

X through simulation of several conditions using

weighted sum w (where ∑

w

=1) of life L, chronic C,

and daily D events.

∀X:AGENT

life_event(X,L)∧ chronic_event(X,C) ∧ daily_event(X,D) →→

neg_event(X, w

1

.L+ w

2

.C+ w

3

.D)

PTS: Positive Attributional Style

If the agent X faces bad situational cues B, negative

events Ne, cognitive depressogenic thought Cd,

adaptive inferential style AiF, and has a proportional

contribution towards positive attributional style

η

then the positive

attributional style level is

η

*AiF+(1-

η

).(1-(B*Ne*Cd)) *AiF

∀X:AGENT

sit_cues(X, B) ∧ neg_event(X, Ne) ∧ adapt_inf(X, AiF) ∧ η ∧

cog_dep_tgt(X, Cd) →→

pos_att_style(X, η*AiF+ (1-η).(1-(B*Ne*Cd))*AiF )

CDI: Cognitive Depressogenic Inferences

If the agent X experiences the intensity levels of

experiences negative inferential style MiF,

situational cues B, cognitive depressogenic thought

Cd, negative events Ne and has a proportional

contribution towards inferences

α

then the cognitive

depressogenic inferences level is

α

*MiF + (1-

α

).(B*Ne*Cd))*MiF

∀X:AGENT

sit_cues(X, B) ∧ neg_event(X, Ne) ∧ maladap _fb(X, MiF) ∧

α ∧ cog_dep_tgt(X, Cd) →→

cog_dep_inf (X, α*MiF + (1-α).(B*Ne*Cd))*MiF)

STR: Stress Reactive Rumination

If the agent X experiences the intensity levels of

cognitive depressogenic thought Cd, and cognitive

depressogenic inference CDi and has a proportional

regulator

β

then the stress reactive rumination level

is

β

* CDi + (1-

β

)* Cd

∀X:AGENT

cog_dep_inf (X, CDi) ∧ cog_dep_tgt(X, Cd) ∧ β →→

sts_reactive(X, β* CDi + (1-β)* Cd )

MDI: Maladaptive Inference

If the agent X faces stress reactive rumination in SR

level and perceives positive attributional style PS

level and has a proportional contribution regulator γ

then the maladaptive inference level is

γ

*SR *(1-PS)

∀X:AGENT

sts_reactive(X, SR) ∧ cog pos_att_style(X, PS) ∧ γ →→

maladap _inf(X, γ*SR *(1-PS))

IMT: Immunity

If the agent X experiences the intensity levels of

cognitive depressogenic thought Cd, and initially has

BiM level of base immunity and has a proportional

Adaptive

inferential

feedback

Maladaptive

inferential

feedback

Negative life

events

Positive

attributional

styles

Cognitive

depressogenic

inferences

Hopelessness

Stress-reactive

rumination

Dysphoric

depressogenic thought

Immunity

Maladaptive

inference

Situational

cues

Social support

provision

Figure 1: Overview of the Cognitive Depressogenic Thought Model.

ICAART 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

234

regulator

λ

then the immunity level (IM) is

λ

*BiIM+(1-

λ

)*(1-Cd)*BiM

∀X:AGENT

cog_dep_tgt (X, Cd) base_im (X, BiM) ∧ λ →→

immunity(X, λ*BiM+(1-λ)*(1-Cd)*BiM)

HPS: Hopelessness

If the agent X faces level of maladaptive inference

MDi and has previous level of hopelessness Hp and

has adaptation rate

ψ

then the hopelessness level for

agent X after

Δ

t is Hp + (1-Hp)*

ψ

*(MDi-Hp)*Hp*

Δ

t

∀X:AGENT

maladap _inf(X, MDi) ∧ hoplness(X, Hp) ∧ ψ →→

hoplness(X, (1-Hp)*ψ*(MDi-Hp)*Hp*Δt)

CDT: Cognitive Depressogenic Thought

If the agent X faces level of hopelessness Hp and

has previous level of cognitive depressogenic

thought Cd and has adaptation rate

ϕ

then the

cognitive depressogenic thought level for agent X

after

Δ

t is Cd + (1-Cd)*

ϕ

*(Hp-Cd)*Cd*

Δ

t

∀X:AGENT

hoplness(X, Hp) ∧ cog_dep_tgt (X, Cd)∧ ϕ →→

cog_dep_tgt (X, Cd + (1-Cd)*ϕ*(Hp-Cd)*Cd*Δt)

4 SIMULATION TRACES

In this section, the model was executed to simulate

several conditions of agents with the respect of

exposure towards negative events, feedbacks from

the social support members, and situational cues.

With variation of these conditions, some interesting

patterns can be obtained, as previously defined in the

earlier section. For simplicity, this paper shows

several cases of cognitive depressogenic thought

levels formation using three different agent

attributes. These cases are; (i) an agent Heidi with a

good feedback from the social support members, and

using a good judgment about the situation (B=0.2,

MiF=0.1, AiF=0.8), (ii) an agent Kees that receives

good feedbacks but with bad judgment about the

situation (B=0.8, MiF=0.1, AiF=0.9), and (iii) an

agent Piet with bad feedbacks from the social

support, and bad judgment about the situation

(B=0.9, MiF=0.8, AiF=0.1). The duration of the

simulated scenario is up to t = 1000 (to represent the

conditions within 42 days) with two negative events.

The first event consisted of the prolonged and

gradually decreased stressors, while the second

event dealt with the decreased stressor. For all

conditions, the initial cognitive depressogenic

thought was initialized as 0.5.

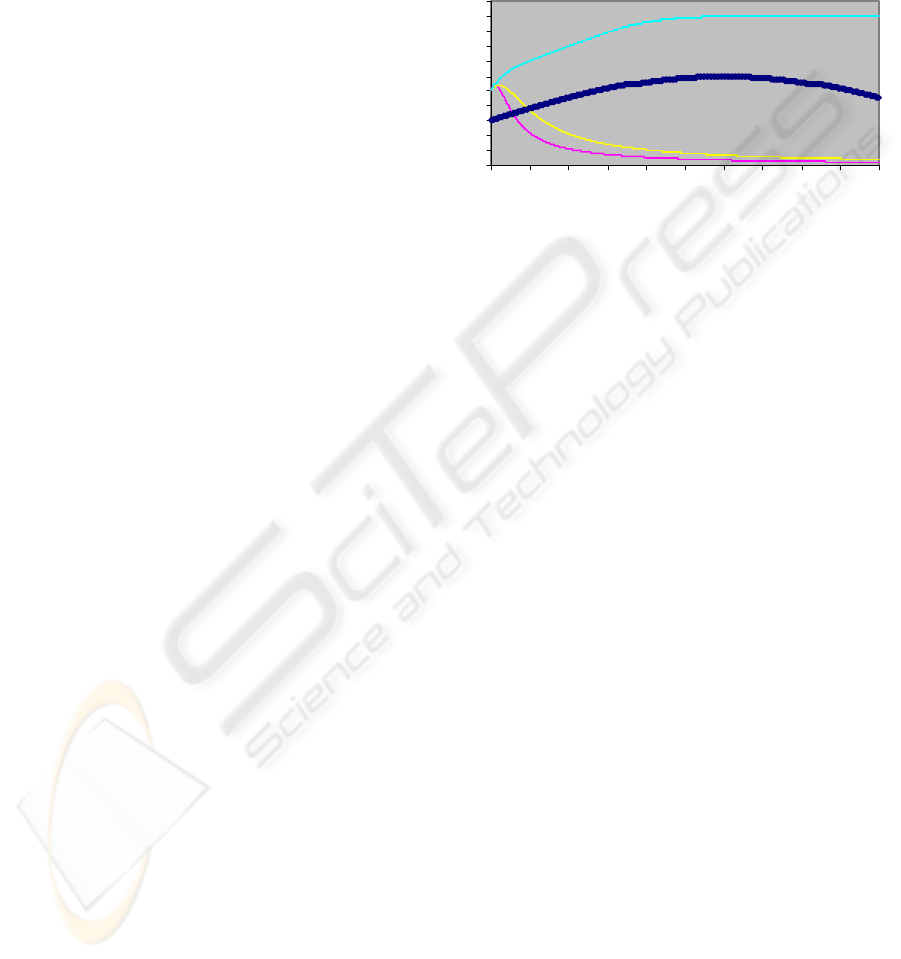

Case #1: Prolonged Repeated Stressor with

Different Individuals Inferential Feedback

and Situation Cues

During this simulation, each type of individual

attribute has been exposed to a prolonged stressor

condition. The result of this simulation is shown in

Figure 2.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

1.1

1 101 201 301 401 501 601 701 801 901

Stressors

Piet

Kees

Heid

i

Figure 2: Cognitive Depressogenic Level for Each

Individual during Prolonged Stress Events.

In this simulation trace, it shown that Piet (high

situational cues, and negative inferential feedback)

tends to develop a cognitive depressogenic thought,

in contrast with the others. Heidi (low situational

cues, and positive inferential feedback) shows a

rapid declining pattern in developing the cognitive

condition. Note that Kees (high situational cues and

positive inferential feedback) has also developed a

decreasing pattern towards the cognitive condition.

However, Kees has a lesser decreasing effect

towards a negative thought despite a high positive

support, given that this individual tends to perceive

negative view about the situation. Persistent positive

support from the social support members helps each

agent to reduce the development of cognitive

thought throughout time

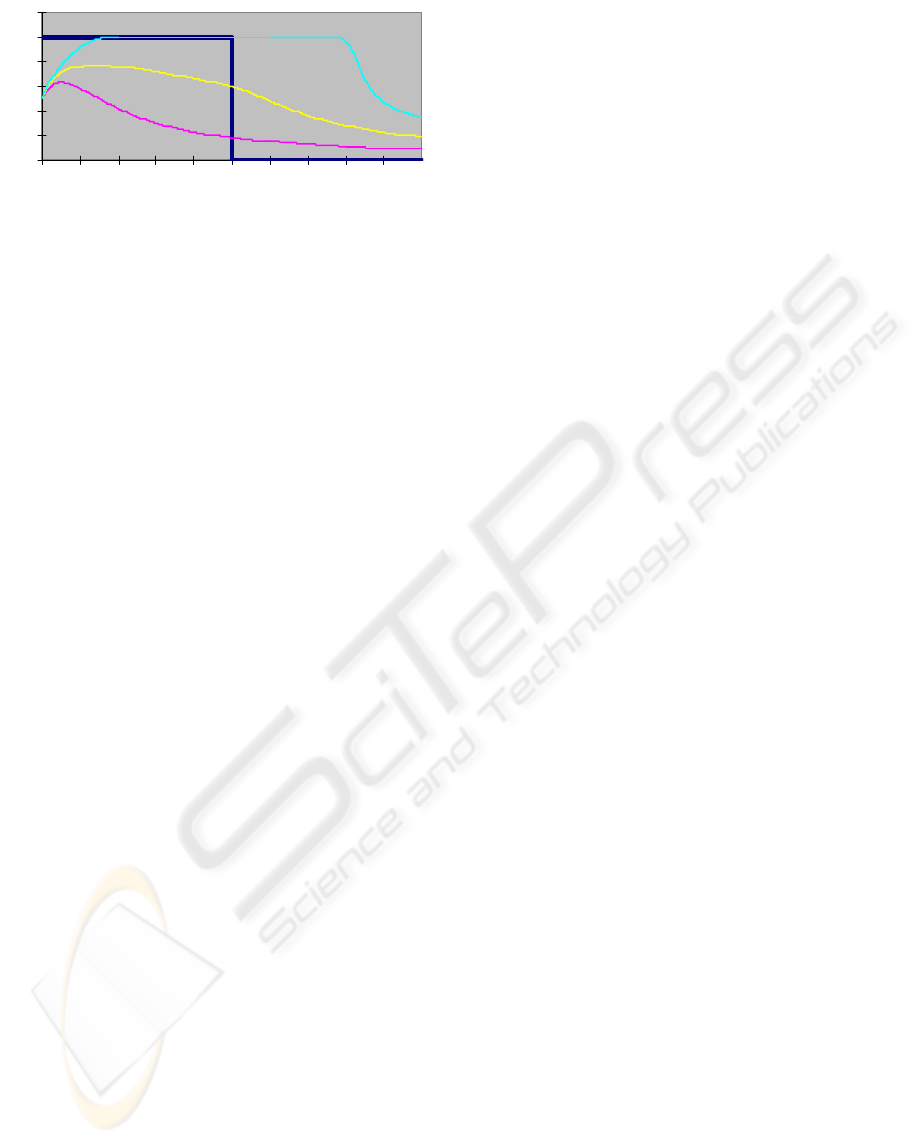

Case #2: Decreased Stressor with Different

Individual Inferential Feedback and

Situational Cues

In this simulation trace, there are two conditions

were introduced, one with a very high constant

stressor, and with no stressor event. These events

simulate the condition of where agents were facing a

sudden change in their life, and how inferential

feedbacks and perceptions towards events play

important to role towards the diminishing of

cognitive thought. The result of this simulation is

shown in Figure 3.

AN AGENT BASED SIMULATION OF THE DYNAMICS IN COGNITIVE DEPRESSOGENIC THOUGHT

235

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1 101 201 301 401 501 601 701 801 901

Stressors

Heidi

Kees

Piet

Figure 3: Cognitive Depressogenic Level for Each

Individual during Fluctuated Stressors.

A comparison for each agent shows that Piet gets

into a sharp progression towards a high cognitive

thought after direct exposure towards a heighten

stressor. At the start of a high constant stressor, both

individuals Heidi and Kees develop cognitive

thought. However, after certain time points, those

progressions dropped and reduced throughout time.

As for Piet, even the stressors have been diminished,

the level cognitive depressogenic thought was still

high for several time points until it decreased.

5 MATHEMATICAL ANALYSIS

By a mathematical formal analysis, the equilibria of

the model can be determined. The equillibria

explains condition where the values for the variables

which no change occur. Assuming all parameters are

non-zero, the list of LEADSTO specifications for

the case of equilibrium for the agent X are:

dCd(t)/dt=(1-Cd)*

ϕ

*(Hps-Cd)*Cd (1)

dHp(t)/dt = (1-Hp)*

ψ

*(MDi-Hp)*Hp (2)

Assuming both adaptation rates are equal to 1,

therefore, these are equivalent to;

Cd=1 or Hp=Cd or Cd=0 (3)

Hp =1 or MDi=Hp or Hp=0 (4)

From here, a first of conclusions can be derived

where the equilibrium can only occur when the

Cd=

1, Hp=Cd

, or Cd=0 (refer to Equation 3). In this

paper, only condition

Cd=1, has been chosen for the

discussion. From this case (

Cd=1), it can be further

derived that respective values for the equilibrium

condition to take place. These values can be

calculated from the following formulae.

CDi =

α

*MiF + (1-

α

)*(B*Ne*Cd)*MiF

PS =

η

*AiF + (1-

η

)* (1-(B* Ne*Cd)).AiF

SR =

β

*[

α

*MiF + (1-

α

)*(B*Ne*Cd)*MiF] + (1-

β

)

MDi =

γ

*[

β

*(

α

*MiF + (1-

α

)*(B*Ne*Cd)*MiF]

+(1-

β

))*(1-(

η

*AiF+(1-

η

)*(1-(B*

Ne*Cd)))*AiF)]

IM =

λ

* BiM

This equillibria describes the condition when

agents are experiencing an intense negative

cognitive thought throughout time will eventually

have their level immunity reduced to the lowest

boundary of agents’ limit. This condition creates

higher vulnerability towards the development of

onset during the present of negative events.

Simulation trace from the experiment #1 confirms

this condition

6 AUTOMATED VERIFICATION

This section deals with the verification of relevant

dynamic properties of the cases considered in the

human agent model, which coherence with the

literatures. The Temporal Trace Langue (TTL) is

used to perform an automated verification of

specified properties against generated traces. TTL is

designed on atoms, to represent the states, traces,

and time properties. This relationship can be

presented as a

state(

γ

, t, output(R)) |= p, means that

state property p is true at the output of role R in the

state of trace

γ

at time point t (Bosse et al., 2009).

Based on that concept, several dynamic properties

can be formulated using a sorted predicate logic

approach. Below, a number of them are introduced

in semi formal and in informal representations.

VP1: Positive Supports will Reduce the Risk

in Developing Future Depressogenic Thought

When an agent X received more positive supports

from its social support networks, then the agent will

unlikely to develop further hopelessness in future.

∀γ:TRACE, t, t’:TIME, R1,R2,R3,MIN_LEVEL:REAL,

X:AGENT

[ state(γ, t) |= adapt_inf (X, R1) & R1 > MIN_LEVEL

state(γ, t) |= cog_dep_tgt (X,R2) & R2 > 0]

⇒ ∃t’:TIME > t:TIME

[state(γ, t’) |= cog_dep_tgt (X,R3) & R3 < R2]

This property can be used to verify future condition

of an agent if the agent receives positive supports

from its social support members throughout time.

Many research works have maintained that positive

supports from members will decrease possibilities of

having further negative thought in future (Heller and

Rook, 1997).

VP2: Negative Perception towards Situation

and Bad Support received from the Social

Support Networks will Increase the Risk of

Further Depressogenic Thought

When an agent X perceives all situations will give

negative impact and an agent X receives bad support

from its social support networks, then the agent X

ICAART 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

236

will almost likely to develop future depressogenic

thought.

∀γ:TRACE, t, t’:TIME, R1,R2,R3,R4, MIN_MLD_LEVEL,

MIN_SC_LEVEL, MAX_CDT_LEVEL:REAL, X:AGENT

[state(γ, t) |= maladap_bf (X, R1) &

R1 > MIN_MLD LEVEL &

state(γ, t) |= sit_cues(X, R2) & R2 > MIN_SC_LEVEL &

state(γ, t) |= cog_dep_tgt (X,R3) & R3 <

MAX_CDT_LEVEL]

⇒ ∃t’:TIME > t:TIME

[state(γ, t’) |= cog_dep_tgt (X,R4) & R4 > R3]

By checking property VP2, one can verify whether

negative perception (situational cues) and bad

support will influence the rise of depressogenic

thought. It is particularly significant to observe this

property in the model given that bad support and

negative perception is highly correlated towards the

development of depressogenic thought (Crossfield et

al., 2002).

7 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, the assumed role of negative cognitive

content in depression is explained. Based on this, a

agent-model is presented that describes the temporal

relation between personal characteristics, negative

life events and social support. This model is used in

a small simulation to investigate the effect of

different types of support on different persons that

undergo similar life events. The mathematical

analysis of the model and the verification of

expected behaviour of the modelled agents in the

simulation traces give some evidence for the

appropriateness of the model.

In the future, we would like to extent the model

with the effect of negative thoughts and a bad mood

on the willingness to offer support. Together with

the existing elements of the model, this would allow

for a multi-agent simulation of a larger community,

in which different persons interact with each other

by giving and receiving support. Such analysis

would make it possible to investigate the

consequences of depressive persons in a small

community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The preparation of this paper would not have been

possible without the support and ideas of Prof. Dr.

Jan Treur. Both authors would like to thank him for

ideas, and refinement of this paper.

REFERENCES

Abramson, L.Y., Alloy, L.B., Hogan, M.E., Whitehouse,

W.G., Donovan, P., Rose, D.T., Panzarella, C.,

Raniere, D. 1999. Cognitive vulnerability to

depression: Theory and evidence. Journal of Cognitive

Psychotherapy, 13, 5-20.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Gibb, B. E., Crossfield, A.

G., Pieracci, A. M., Spasojevic, J., Steinberg, J. A.

2004. Developmental antecedents of cognitive

vulnerability to depression: Review of findings from

the cognitive vulnerability to depression project.

Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 18(2), 115-133.

Aziz, A.A., Klein, M.C.A., Treur, J. 2009. An agent model

of temporal dynamics in relapse and recurrence in

depression. In: Ali, M., Chen, S.M., Chien, B.C.,

Hong, T.P. (eds.), IEA-AIE 2009. LNAI, Springer

Verlag, pp. 36-45.

Beck, A.T. 1987. Cognitive models of depression, Journal

of Cognitive Psychotherapy 1, pp. 5–37.

Bosse, T., Jonker, C.M., Meij, L. van der, Treur, J. 2007.

A language and environment for analysis of dynamics

by simulation. International Journal of Artificial

Intelligence Tools, vol. 16, pp. 435-464.

Bosse, T., Jonker, C.M., Meij, L. van der, Sharpanskykh,

A., Treur, J. 2009. Specification and verification of

dynamics in agent models. International Journal of

Cooperative Information Systems, vol.18, pp.167 - 193

Coyne, J.C. 1990. Interpersonal process in depression. In:

G.I. Keitner, Editor, Depression and families: Impact

and treatment, American Psychiatric Press,

Washington, DC , pp. 31–53.

Crossfield, A. G., Alloy, L. B., Gibb, B. E., Abramson, L.

Y. 2002. The development of depressogenic cognitive

styles: The role of negative childhood life events and

parental inferential feedback. Journal of Cognitive

Psychotherapy, 16(4), 487–502.

Dobkin, R.D, Panzarella, C., J. Fernandez, Alloy, L.B.,

Cascardi, M. 2004. Adaptive inferential feedback,

depressogenic inferences, and depressed mood: A

laboratory study of the expanded hopelessness theory

of depression, Cognitive Therapy and Research, pp.

487–509.

Heller, K., Rook, K.S. 1997. Distinguishing the theoretical

functions of social ties: Implications for support

interventions. In: S. Duck, Editor, Handbook of

personal relationships: Theory, research, and

interventions, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester,

England, pp. 649–670.

Panzarella, C., Alloy, L.B., Whitehouse, W.G. 2006.

Expanded hopelessness theory of depression: On the

mechanisms by which social support protects against

depression, Cognitive Therapy and Research 30 (3),

pp. 307–33

Robinson, M. S., Alloy, L. B. 2003. Negative cognitive

styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to

predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive

Therapy & Research, 27(3), 275-292.

Spasojevic, J., Alloy, L. B. 2001. Rumination as a

common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to

depression. Emotion, 1(1), 25-37.

AN AGENT BASED SIMULATION OF THE DYNAMICS IN COGNITIVE DEPRESSOGENIC THOUGHT

237