DESIGNING

A PHYSICIAN-FRIENDLY INTERFACE FOR AN

ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD SYSTEM

Donald Craig and Gerard Farrell

eHealth Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada

Keywords:

Electronic health record, User interface design, Data visualization, Physician workflow, Knowledge manage-

ment, Usability, Medical chart.

Abstract:

An Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system enables a physician to record patients’ health information, re-

quest reports from third partly health care providers and retrieve these reports when they are ready. Despite

the numerous benefits of EMRs, several factors have inhibited their widespread adoption. An underappreci-

ated but critical factor has been the proliferation of inferior user interfaces which are confusing to navigate

and disruptive to a physician’s workflow. To be useful, an EMR must allow physicians to record and query

information in a natural manner that accommodates the non-linear nature of their workflow. In particular,

an interface must permit a physician to record the minutiae of a patient’s condition while at the same time

preserving the physician’s overview of a patient’s record so that any aspect of the patient’s health can be ef-

fortlessly queried and inspected. This paper proposes an interface design that attempts to address several of

the usability deficiencies associated with current electronic medical record systems in use today.

1 INTRODUCTION

Electronic Medical Record (EMR) systems (Carter,

2008) are providing an increasingly viable mecha-

nism for physicians to record and retrieve patient re-

lated information. The potential benefits of such sys-

tems are well documented in the literature: a properly

designed EMR can help reduce medical errors, en-

hance communication between physicians and health

care providers and provide a more readily accessible

and comprehensive integration of several aspects of a

patient’s health record (Cimino and Shortliffe, 2006).

Unfortunately, despite the benefits of EMR sys-

tems, their rate of adoption has been slow relative

to the integration of information technology tools

into other occupations (Thompson and Dean, 2009).

The challenges encountered when deploying EMRs

in medical practices are numerous and varied (Baron

et al., 2005). Several reasons have been offered to ex-

plain the poor penetration of technology in the health

care sector. According to a recent study (Jha et al.,

2009), various financial and administrative issues are

often cited by hospitals as reasons for the poor adop-

tion of electronic medical record systems.

Surprisingly, this study also showed that physician

resistance is stronger in hospitals that have adopted

an EMR system than in hospitals without an EMR.

This suggests that current EMR technology may be

at best inadequate and at worst counter-productive in

addressing the needs of physicians. Indeed, techni-

cal issues related to the usability of EMRs have been

cited as a reason for the low acceptance rates of EMRs

in hospitals and clinics (Miller and Sim, 2004). Given

this, instead of capital investments in systems which

have a high risk of physician resistance and rejec-

tion, it may be wiser to investigate alternative inter-

face technologies that are more amenable to physi-

cians’ practices and workflows.

The interface design proposed by this paper al-

lows for a natural recording of patient related infor-

mation while simultaneously permitting seamless re-

quest and retrieval of reports from a variety of sources

related to a patient’s broader electronic health record.

This is done without having to navigate a myriad of

menu items and to tediously fill numerous data entry

fields presented in pop-up modal dialog boxes. By

streamlining the interface in this manner, we believe

that physicians will become less reticent to adopting

EMRs.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 gives

an overview of the challenges associated with the de-

sign of user interfaces for EMR systems and describes

324

Craig D. and Farrell G. (2010).

DESIGNING A PHYSICIAN-FRIENDLY INTERFACE FOR AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD SYSTEM.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 324-329

DOI: 10.5220/0002746003240329

Copyright

c

SciTePress

some of the problems encountered by physicians as

they use the systems currently available. Section 3

presents the proposed interface design, which repre-

sents the primary contribution of this paper. Section 4

provides a discussion of some of the issues regarding

the interface design and presents opportunities for fu-

ture work. Finally, conclusions are presented in Sec-

tion 5.

2 EMR USER INTERFACE

ISSUES

The user interface of a viable EMR should provide

a portal through which all aspects of patients’ health

record can be seamlessly and accurately recorded and

retrieved. Moreover, the EMR interface must permit

requisition of orders and the subsequent reception of

results from a wide variety of healthcare sources. All

this information must then be made easily accessible

to the physician and presented in a meaningful way

by the EMR.

The literature suggests two aspects that are par-

ticularly important with respect to the usefulness of

an EMR to physicians: the recording of information

into the EMR and the navigation of the interface itself.

The goal of this paper is to present an EMR design

that makes it easier for the physician to accomplish

these tasks. The challenges associated with these is-

sues are discussed in the following subsections.

2.1 Recording Patient Information

Paper records offer physicians enormous flexibility

when documenting and annotating patient informa-

tion (Reuss et al., 2007). Unfortunately, the inter-

face for many electronic health record systems em-

phasize capturing patient data in a highly structured

or restricted coded form. In recent studies, it has been

shown that some physicians regularly eschew coded

data entry, opting instead to record patient informa-

tion in free-form text (Zheng et al., 2009). Providing

physicians the ability to record free-form text offers

them the flexibility to enter information in an order

and manner which is most appropriate to their per-

sonal workflow and style.

While coded and/or structured data can be useful

for clinical decision support and administrative pur-

poses such as report generation, forcing a physician

to pigeon-hole clinical observations may result in in-

formation critical to patient care being omitted from

the patient’s health record or recorded in the wrong

“box.” Information which is outside the domain cov-

ered by the restricted coded data of the required by the

software may subsequently be forgotten or not com-

municated to relevant parties.

During an encounter, patients often communicate

their complaints and symptoms to the physician in the

form of a story. For many physicians, accurately cap-

turing these stories (also known as patient narratives),

is essential to patient care (Walsh, 2004). An EMR

designer must appreciate the physician’s need to cap-

ture all aspects of the patient’s narrative during the en-

counter and allow the physician to construct the nar-

rative in a natural manner. Allowing the physician

to enter information using free-text offers more flex-

ibility over more restrictive structured or coded data

entry. As a result, the method of data entry becomes

more fluid and accommodating for the physician.

Ultimately, an EMR must never force the physi-

cian to forget that he or she is recording information

from a patient and not just recording information to a

database. By making the entry of patient information

more natural to the physician, the disruption to com-

munication between the physician and patient is kept

at a minimum.

2.2 Workflow and Interface Navigation

The importance of document management and the

clerical tasks implicitly performed by physicians must

be acknowledged in the design of an EMR interface.

In particular, patient information must be immedi-

ately accessible and not hidden within a labyrinth of

windows or dialog boxes (Rose et al., 2005). For ex-

ample, navigating between physician orders and their

associated results should be seamless and natural.

Physicians often complain about the “loss of

overview” as they navigate an EMR interface (Ash

et al., 2004). This loss of overview can be caused or

exacerbated by the plethora of pop-up windows or di-

alog boxes that are used by some EMRs to present

or request information or to alert physicians about

exceptional circumstances such as potentially seri-

ous drug-drug interactions (Grossman et al., 2007).

Sometimes, these dialog boxes are implemented as

“modal windows” which prevent the physician from

continuing until the event has been addressed. Such

modal dialog boxes are distractive and have been

shown to introduce inefficiencies in a physician’s

workflow (Belden et al., 2009).

The navigation of an EMR interface should be

very accommodating to a physician’s unique style and

needs. Retrieval of relevant information from a vari-

ety of sources should be efficient and tasks such as or-

ders and requisitions should be performed with a min-

imal number of steps. The numerous health events

that occur during the care of a patient must be pre-

DESIGNING A PHYSICIAN-FRIENDLY INTERFACE FOR AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD SYSTEM

325

sented in a way that is contextually meaningful but

without overwhelming the physician or cluttering the

user interface. Details regarding these events and their

interactions with one another must be made readily

available by the interface.

Some of the inefficiencies associated with EMR

navigation may be attributed to fundamental aspects

of the underlying EMR architecture bubbling up to

the interface itself. When EMRs allow database ab-

stractions and other low-level implementation details

to bleed into the user interface, a physician may be-

come infected by technical considerations that are un-

related to the immediate care of his or her patients.

These artifacts can cause a physician to lose overview

during the assessment and planning phases of a pa-

tient’s treatment; patient care may degrade as a result.

By reducing or eliminating conventional user-

interface elements such as modal pop-up windows,

pull-down menus, buttons, checkboxes, lists, etc., a

more streamlined interface that offers free-text entry

and easier navigation can be developed. The basic

foundation for this interface is proposed in the next

section.

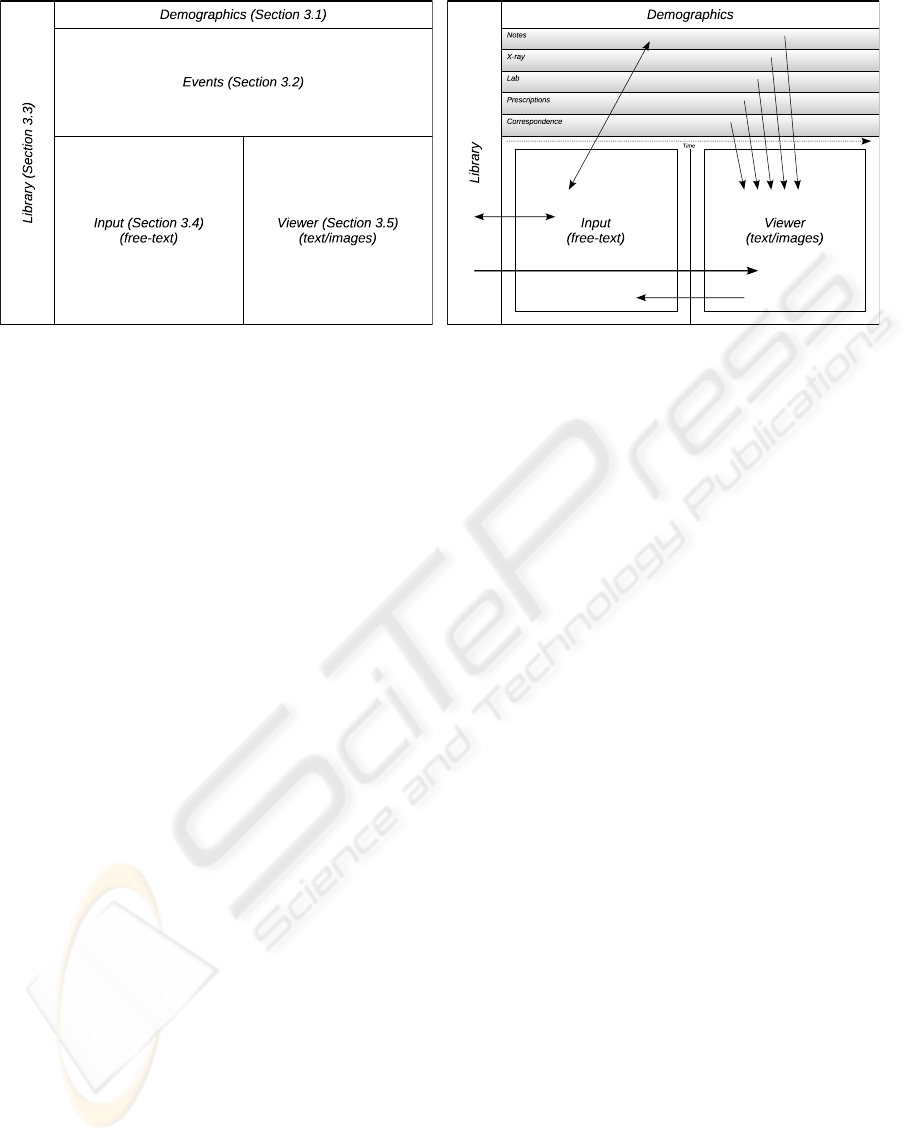

3 INTERFACE DESIGN

To address the issues described in the previous sec-

tion, the proposed interface design presents to physi-

cians a pane-based view of the patient record, as

shown in Figure 1. This interface is designed to of-

fer physicians a broad overview of the patient record

while allowing them to quickly focus on smaller de-

tails as the need arises.

As the physician records and retrieves clinical in-

formation to and from the EMR during the patient en-

counter, the interface does not change considerably

from one view to the next. No disruptive or obstruc-

tive pop-up windows are ever displayed by the inter-

face. In particular, the physician is not required to

navigate an abundance of windows and dialog boxes

in order to record or retrieve information to and from

the EMR, regardless of whether the information being

retrieved is local or remote. In addition to offering a

more natural workflow, this interface may help reduce

the loss of overview for the physician. The compo-

nents of the interface are described in further detail in

the following subsections.

3.1 Demographics Pane

The Demographics pane at the top of the window sim-

ply contains generic information about the patient,

such as name, age, date of birth and address. Unlike

other panes, the demographic pane cannot be resized

or closed — it is always present so that that the physi-

cian never loses focus of the patient currently being

treated. This helps to maintain overview, as described

in the Section 2.2.

The demographics pane can also be used to navi-

gate to other patients. As data is entered in the various

fields of this pane, the contents of the Viewer pane

below it will contain a list of patients that satisfy the

supplied criteria. Patients can then be selected from

this list and their associated details will be presented

in the Events pane.

3.2 Events Pane

The Events pane provides a segregated, time-ordered

view of a single patient’s health events (Bui et al.,

2007). This puts the entire patient’s history in tem-

poral context and offers the physician a “big picture”

view of the patient’s general history. This user inter-

face element is the primary vehicle used for navigat-

ing the patient chart and for maintaining a physician’s

overview of the patient record. As shown in Fig-

ure 1(b), this pane is divided into subpanes, each of

which correspond to various domains of health infor-

mation. There are five broad domains containing the

Notes

recorded by the physician,

Lab reports

,

X-ray

reports

,

Prescriptions

and

Correspondences

related to

the patient. Each of these subpanes can be expanded,

collapsed, zoomed and scrolled to reveal more or less

information as required by the physician.

Events are represented by small squares (colloqui-

ally referred to as rhondots) within the subpane. The

horizontal position of each event represents the date

the event took place, whereas the vertical placement

indicates the time of day the event occurred.

Events that are related to one another can be

connected by arrows, thereby making it clear which

events were triggered by an initiating event. This

would enable a threaded event viewer across several

provider domains, making it relatively easy to find the

originating order for a given lab result, for example.

Such a feature would rely upon the underlying com-

munication infrastructure using consistence reference

identifiers to relate the events together.

Colours and other visual attributes can be used

to indicate the urgency of the events. For example,

green could be used to represent normal events, while

blue and red could be used to represent abnormal and

critical/important events, respectively. Unread events

can be represented by a square; events that have been

viewed by the physician can be changed to circles.

More details on each event can be viewed by drag-

ging its square to the Viewer pane. An event can be

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

326

(a) Main Layout (b) Events Subpanes and Workflow

Figure 1: Interface Design Layout. The topmost pane shown in 1(a) contains patient demographics. The pane immediately

below contains a graphical representation of all the patient’s health events. To the left is a pane containing a generic library of

resource materials that can be queried by the physicians during input. Finally, the two panes at the bottom are used to record

and display detailed patient information. Figure 1(b) shows the collection of subpanes within the Events pane that contains

clinical data from a variety of sources. This pane of panes provides the physician with a broad, time-ordered overview of all

the patient’s information currently available to the physician from a variety of sources. Each event would be represented by

squares or dots (not shown). The arrows represent the general workflow that occurs between the panes.

annotated by dragging it to the Input pane, adding the

annotation, and dragging it back to the event pane; a

new note linked with the original event will then be

created in the

Notes

subpane. Context menus (acti-

vated by right clicking the mouse in the subpane) can

be used to select and plot various quantifiable data

items extracted from the events contained in that sub-

pane. An Events subpane can be expanded, if neces-

sary, to make the plots easier to read.

3.3 Library Pane

The Library pane is a vertical container along the

left hand side of the display which acts as a repos-

itory for a generic collection of clinical practice

guidelines, templates, formularies, patient educa-

tional pamphlets, diagnostic checklists, requisitions,

etc. Each element in the library has a title and a body

of associated text. The titles are arranged in alpha-

betical order in the pane. To prevent titles from over-

lapping, only frequently referenced titles are initially

displayed and accessible inside the pane. Dragging

these to the Input or Viewer panes will cause the ti-

tle’s corresponding body of text to be placed in the

appropriate pane. As with the subpanes in the Events

pane, the library pane can be zoomed and scrolled as

needed.

In addition to dragging information out of the Li-

brary pane, the contents of this pane can be queried

directly as information is entered in the Input pane.

The physician can add new resources to the li-

brary simply by writing text in the Input pane and then

dragging it to the Library pane. The first line of the

text can be used as the title. A body of medically re-

lated information can be programmatically imported

into the library, if necessary, as part of the installa-

tion procedure of the EMR in the physician’s office.

The Library pane may also contains documentation

related to the usage of the EMR itself, which can be

requested by making queries in the Input pane (see

below).

3.4 Input Pane

All information that the physician wishes to record in

the EMR is done via the Input pane. All progress and

SOAP notes as well as requisitions, prescriptions and

correspondences are created here in a relatively free-

text manner. Once the note is finished, it is dragged to

the Events pane where it will automatically be stored

in the

Notes

subpane. Generic information not par-

ticular to any patient can also be created here and

dragged to the Library, as described above.

The objective of the Input pane is to provide the

physician more flexibility when recording patient in-

formation than is offered by traditional EMRs that

may require a large amount of structured or coded

data entry. This pane is intended to serve the same

purpose as the blank piece of paper in a traditional

chart — the physician has the ability to record un-

structured text to capture the patient narrative in a way

most natural to his or her style.

DESIGNING A PHYSICIAN-FRIENDLY INTERFACE FOR AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD SYSTEM

327

As the physician types the note, dynamic analy-

sis of the text and data extraction takes place. This

means that as characters are typed, words and phrases

can automatically change colour to inform the physi-

cian that something of interest has been understood

by the EMR. This provides the physician with instant

feedback that the EMR has successfully extracted in-

formation from the note. For example, quantitative

data such as heart rate and blood pressure could be

identified, provided a consistent syntax is used.

Notes are traditionally subdivided into coarse sec-

tions. For example a SOAP note has subjective, ob-

jective, assessment and plan sections. As various sub-

section heading text is entered by the physician, the

editor would enter different contextual modes of op-

eration which would affect the dynamic analysis of

the following text.

Ideally, all prescriptions and requisitions for lab

work or diagnostic could be made inside the Input

pane. This makes prescriptions and requisitions pos-

sible without having to navigate through numerous

pop-up screens and meticulously enter coded data

along the way (possibly losing patient overview in

the process). Any incomplete or erroneous requisi-

tions and dangerous prescription interactions could be

detected dynamically and reported in an unobtrusive

manner to the physician by turning the background

colour of the text red with an annotation indicating

the problem, for example.

The success of this Input pane interface depends,

in large part, on how well the dynamic text processing

algorithm can glean the intentions of the physician as

they construct their patient notes and requisitions (Ja-

gannathan et al., 2009). By having physicians adopt

modest syntactic conventions as part of their note tak-

ing, we believe that it will be possible to construct a

text processor that will be able to provide the physi-

cian with useful real-time feedback during the note

taking process.

3.5 Viewer Pane

The Viewer pane is used to display a wide variety

of data related to the patient chart. Events from the

Events pane can be dragged and dropped onto this

pane and the pane will render the contents of the event

in a human readable format. The contents could be

either text, images or a combination of both. Annota-

tions of the event can be made by dragging the event

to the Input pane, making the annotation, then drag-

ging it back to the Events pane.

4 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE

WORK

A prototype of this EMR is under development. The

current plan is to develop a web-based application

so as to ensure easy deployment across a wide va-

riety of computing platforms. The Bespin project

from Mozilla labs

(https://bespin.mozilla.com/)

im-

plements an editor component that may be useful for

entering medical notes in the context of the Input pane

described in Section 3.4.

The true measure of viability of the EMR inter-

face design described by this paper can only be made

once the construction of a working prototype that im-

plements the design is complete. Initially, it is ex-

pected that preliminary implementations of the EMR

will be used by medical school students in their first

or second year as an elementary training tool. Vari-

ous surveys and evaluations will be conducted on both

the students and their instructors for the purposes of

gathering feedback regarding the usefulness of the ap-

plication and to obtain suggestions for potential im-

provements. The remainder of this section describes

some of the problems that are anticipated and pro-

vides some possible mitigations.

Due to the free-text nature of the input, much work

remains in defining all the necessary syntactic clues

that would be used in the Input pane to allow the

physician to intuitively record and query patient in-

formation. For example, the exact details of the query

syntax and the format of the CPOE and prescription

sections of a note need to be addressed. When design-

ing the grammatical and syntactic format for these el-

ements, care must be taken to make the input as natu-

ral as possible so as not to make the EMR frustrating

or cumbersome to use by the physician.

The user interface should allow the partitioning of

events that are displayed in the Events pane accord-

ing to a patient’s specific problem. For example, it

should be possible to isolate those medical events per-

taining to a patient’s cancer treatment, while ignor-

ing events related to her broken hip. This would re-

duce the amount information presented to the physi-

cian and allow him or her to focus on a specific condi-

tion. A syntactically consistent textual tagging mech-

anism used within the free-text note may be helpful in

this regard.

Finally, the current web-based design of the in-

terface is somewhat unconventional in that it does

not present the physician with a traditional pull-down

menu system common in other traditional computer

applications. Furthermore, requiring all data be en-

tered as free-text may impose a burden on physi-

cians who are accustomed to having their notes tran-

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

328

scribed by someone else. However, many students

currently entering medical school are already familiar

with many web-based applications and have superior

keyboarding skills, making this less of an issue.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper proposes an interface design for an elec-

tronic medical record system that attempts to rectify

many of the problems encountered by physicians us-

ing existing EMRs to enter and query patient data.

The interface provides a more natural and less restric-

tive method of data entry by allowing the physician to

enter free-form text that undergoes dynamic extrac-

tion of quantifiable data and orders. Furthermore, by

making the navigation of various components of the

patient more efficient, we believe that the design of-

fers a fluid interface which is amenable to a physi-

cian’s workflow. As such, the work represented here

is still in progress — during the upcoming implemen-

tation and survey phases of this research, shortcom-

ings in this design will be uncovered and addressed,

along the lines as described in Section 4.

While this interface will require training in or-

der to use effectively, we believe that it can help in-

crease the productivity of a physician once this learn-

ing curve has been conquered. While this particu-

lar interface may not be suitable for all physicians,

we believe that the design presents a novel means

of interacting with a patient chart that may appeal to

physicians who have rejected such systems in the past,

thereby helping to increase EMR adoption.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the members, past

and present, of the Medical Informatics Group at

Memorial University whose ideas and suggestions

helped form the basis of the design work presented

in this paper.

REFERENCES

Ash, J. S., Berg, M., and Coiera, E. (2004). Some Un-

intended Consequences of Information Technology in

Health Care: The Nature of Patient Care Information

System-related Errors. Journal of the American Med-

ical Informatics Association, 11(2):104–112.

Baron, R. J., Fabens, E. L., Schiffman, M., and Wolf, E.

(2005). Electronic health records: Just around the cor-

ner? Or over the cliff? Annals of Internal Medicine,

143(3):222–226.

Belden, J. L., Grayson, R., and Barnes, J. (2009). Defin-

ing and testing EMR usability: Principles and pro-

posed methods of EMR usability evaluation and rat-

ing. HIMSS EHR Usability Task Force.

Bui, A., Aberle, D., and Kangarloo, H. (2007). Timeline:

Visualizing integrated patient records. IEEE Trans-

actions on Information Technology in Biomedicine,

11(4):462–473.

Carter, J. H., editor (2008). Electronic Health Records,

second edition. American College of Physicians,

Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Cimino, J. J. and Shortliffe, E. H., editors (2006). Biomed-

ical Informatics: Computer Applications in Health

Care and Biomedicine, third edition, chapter 2, pages

46–79. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., Secaucus,

NJ, USA.

Grossman, J. M., Gerland, A., Reed, M. C., and Fahlman,

C. (2007). Physicians’ experiences using commercial

e-prescribing systems. Health Affairs, 26(3):w393–

404.

Jagannathan, V., Mullett, C. J., Arbogast, J. G., Halbritter,

K. A., Yellapragada, D., Regulapati, S., and Bandaru,

P. (2009). Assessment of commercial NLP engines for

medication information extraction from dictated clin-

ical notes. International Journal of Medical Informat-

ics, 78(4):284–291.

Jha, A. K., DesRoches, C. M., Campbell, E. G., Donelan,

K., Rao, S. R., Ferris, T. G., Shields, A., Rosenbaum,

S., and Blumenthal, D. (2009). Use of electronic

health records in U.S. hospitals. New England Journal

of Medicine, 360(16):1628–1638.

Miller, R. H. and Sim, I. (2004). Physicians’ use of elec-

tronic medical records: Barriers and solutions. Health

Affairs, 23(2):116–126.

Reuss, E., Naef, R., Keller, R., and Norrie, M. C. (2007).

Physicians’ and nurses’ documenting practices and

implications for electronic patient record design. In

Holzinger, A., editor, HCI and Usability for Medicine

and Health Care, volume 4799 of Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, pages 113–118. Springer-Verlag

New York, Inc.

Rose, A. F., Schnipper, J. L., Park, E. R., Poon, E. G., Li,

Q., and Middleton, B. (2005). Using qualitative stud-

ies to improve the usability of an EMR. Journal of

Biomedical Informatics, 38(1):51–60.

Thompson, S. M. and Dean, M. D. (2009). Advancing in-

formation technology in health care. Communications

of the ACM, 52(6):118–121.

Walsh, S. H. (2004). The clinician’s perspective on elec-

tronic health records and how they can affect patient

care. British Medical Journal, 328(7449):1184–1187.

Zheng, K., Padman, R., Johnson, M. P., and Diamond, H. S.

(2009). An interface-driven analysis of user interac-

tions with an electronic health records system. Jour-

nal of the American Medical Informatics Association,

16(2):228–237.

DESIGNING A PHYSICIAN-FRIENDLY INTERFACE FOR AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD SYSTEM

329