HOW BLENDED LEARNING CLOSES THE LANGUAGE GAP

BETWEEN NATIVE STUDENTS AND SPANISH LANGUAGE

LEARNERS

Pablo Ortega Gil and Francisco Arcos García

Department of English Philology, Arts Faculty, University of Alicante, Campus de Sant Vicent del Raspeig

Apartado de correos 99, E-3080 Alicante, Spain

Keywords: Spanish language learners, Immigration, Blended learning, Learning Management System, Moodle,

Interaction.

Abstract: Children of immigrant families with little or no knowledge of Spanish are referred to as Spanish language

learners (SLL). During their first year in Spain, they spend some hours in pullout groups for learning the

language, but many of them do not develop academic Spanish even after four or five years of schooling. As

a supplement to those pullout groups and special programs, interactive tasks (integrated in a Learning

Management System LMS such as Moodle) can greatly improve the linguistic abilities of SLLs for a

number of reasons. First, these tasks often include recordings of academic Spanish. Second, some of these

tasks involve working cooperatively with several native speakers. Finally, interactive tasks within an LMS

can be done outside the limited framework of school time because they are open and ready to be used

24/365 days a year. The article provides details of an LMS for SLLs being actually used at a secondary

school. The school had 15 SLL students enrolled in an experimental project involving the LMS while

another group of 15 SLL students went on doing the traditional pullout groups. The results show that those

in the first group have learnt faster and deeper than those in the second one.

1 SPANISH LANGUAGE

LEARNERS

The last decade has seen a surge in immigration.

Whole families have left their countries and moved

to Western countries in search of better

opportunities. The children of these families join

their new schools sometimes without any knowledge

of the language in which instruction is given. This

has happened very frequently in South Eastern Spain

as a consequence of unprecedented economic

expansion, where some secondary schools have had

up to 30% of Spanish language learners (SLL).

Although some of these newly arrived students came

from Spanish speaking countries in Central or South

America, most were originally from Morocco, from

Eastern European countries (such as Romania,

Bulgaria, Ukraine or Russia), and also from Asia

(mainly from China and Pakistan).

When joining the Spanish educative system,

these students often face a double language

challenge: they must not only learn Spanish but also

the regional dialect (Valencian in our case), which is

used in teaching a varying number of subjects

(ranging from two to eight). With little or no ability

in Spanish and certainly none at all in Valencian,

SLLs go through an initial buffer period during

which they spend some hours in pullout groups or

special programs for learning the language. Then,

they share with their native classmates those subjects

of a practical nature (arts, sports, technology, and so

on) to get used to ordinary lessons in Spanish or

Valencian.

To help these students overcome the problems

they usually face, we used a Learning Management

System (LMS), in our case Moodle. Our project

included 15 SLLs while another group of 15 SLLs

remained exclusively in the pullout group. Both

groups followed the same syllabuses and did similar

tasks (the content was identical although the

appearance of the exercise may differ). The tasks

were numbered to allow for comparison at the end of

the project.

90

Ortega Gil P. and Arcos García F. (2010).

HOW BLENDED LEARNING CLOSES THE LANGUAGE GAP BETWEEN NATIVE STUDENTS AND SPANISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 90-95

DOI: 10.5220/0002777000900095

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 AN UNCOMFORTABLE

CHASM

However, the fact is that many of these students do

not develop academic Spanish even after four or five

years in Spain. Academic language is (Hill and

Flynn, 2006: 26) “the language of the classroom…

[which] students must master… to understand

textbooks, write papers and reports, solve

mathematical word problems, and take tests”. While

interviewing teachers of SLLs, once and again we

heard the same story: you see newcomers talking to

or playing with their classmates, as if the Spanish

language was completely natural to them, but as

soon as they get into the classroom everything is

changed: they seem to recede back to a previous

stage of linguistic ability, they showed little or no

interest in communicating with others and, when

questioned by the teacher, answered with a blank

stare.

In order to perform well at school, SLLs must

master academic Spanish. When they fail to do so

after several years in Spain, the gap between them

and their peers widens and widens until it becomes

insurmountable. Then, there is a second fact which

amplifies the one just explained (Nieto, 2002): many

mainstream teachers admit they feel unprepared to

work with language learners. These are teachers of

instrumental subjects with no linguistic training

who, faced with the challenge which SLLs pose, feel

overwhelmed and helpless.

Add the first circumstance to the second and you

have found the formula of academic failure. With all

these things in mind, it goes without saying that

SLLs are at the highest risk of dropping out. At the

schools we supervised, the number of SLLs who

dropped out doubled that of native Spanish students

(72% against 34 %). It was even higher for boys (81

% against 47%) and slightly less grievous for girls

(40% against 28%). These figures, obtained by us,

offer a glimpse of an uncomfortable chasm between

newcomers and native students, as the former,

deprived of literacy and with a poor knowledge of

the language, leave school early with heavy odds for

a life of exclusion and marginality.

It must be remembered that the recent Spanish

Educational Act, known as Organic Law of

Education, is inspired by several principles, the

second of which is the following (2007: 33): “Equity

that guarantees equal opportunities, educational

inclusion and non-discrimination and that acts as a

compensating factor for the personal cultural,

economic and social inequalities, with special

emphasis on those derived from disabilities”.

Therefore, everyone in the school system is

under the obligation of fighting against the situation

depicted above. The following point explains our

contribution.

3 DEVISING THE PLATFFORM

The authors have written papers on the use of

blended learning for different target student groups:

struggling students (Ortega and Arcos, 2009a),

truants (2009e), youths at risk (2009b), special needs

students (2009d), as well as for specific purposes,

such as homework (2008) and digital storytelling

(2009c). The first thing we did was to bring into the

platform our own experience as teachers of a second

language. Among other things, we planned

instruction with the five stages of second language

acquisition in mind. These five stages, first posited

by Steve Krashen and Tracy Terrell (1983), are:

1. Preproduction, which takes the first six

months of learning.

2. Early production, which goes from the

seventh to the twelfth month.

3. Speech emergence, which occurs between

the end of the first year and the end of the

third year.

4. Intermediate fluency, which goes from the

end of the third year to the end of the fifth

year.

5. Advanced fluency, which occurs between

the end of the fifth year and the end of the

seventh year.

Each of these stages demands for its own

techniques and strategies, and for that reason we

made an initial assessment of all the students in the

project. Once they were assigned their own stage of

second language acquisition, we selected those in

stages 1, 2 and 3 because we thought the tasks at the

platform would work best with them. For students in

stages 4 and 5, more specific measures were

advised, such as one-to-one conversations with their

teachers, oral expositions and accuracy exercises

designed to correct their individual language errors.

Next we established a time frame: the students in

the project would use the LMS for one academic

year, at the end of which there would be an

assessment of the results. The idea was that, apart

from the hours spent in the pullout groups,

mainstream teachers would prepare interactive tasks

for Moodle in order to promote understanding and

the development of academic Spanish. Some

teachers who felt uncomfortable or unconfident with

SLLs volunteered, hoping that blended learning

HOW BLENDED LEARNING CLOSES THE LANGUAGE GAP BETWEEN NATIVE STUDENTS AND SPANISH

LANGUAGE LEARNERS

91

would solve their communication problems. They

taught, among others, such instrumental subjects as

Maths, Science or Geography.

The underlying principle to all the tasks was

schema theory, according to which learning occurs

when we connect the new information being

received to background knowledge or knowledge

previously acquired, called schemata. Therefore,

when we receive a message, we not only use the

words in it to obtain its meaning, but also make use

of our knowledge of similar messages, which is

stored in our memory (internal schemata).

According to Omaggio (1986: 102), “there are two

basic kinds of schemata used in interpreting

messages; content schemata (relating to the

individual´s background knowledge of the world and

expectations about objects, events, and situations)

and formal schemata (relating to the individual´s

knowledge of the rhetorical or discourse structures

of different types of texts)”.

Being grounded on schema theory, all tasks

began with a simple instruction: “Before you begin

doing this task, take a couple of minutes to answer

the following question: what do you already know

about this topic?” The point, as can be imagined,

was to activate background knowledge. Next, some

advance organizers were given. Advance organizers

are (Hill and Flynn, 2006: 31) “organizational

frameworks presented in advance of lessons that

emphasize the essential ideas in a lesson or unit.

They focus student attention on the topic at hand and

help them draw connections between what they

already know and the new knowledge to be learned.”

As an example, these are the instructions given

for understanding a Science lesson done with

eXeLearning:

1 Skim through the text: make sure you

understand the title and the headings; look at the

pictures and find why they are relevant to this

lesson; can you foresee and foretell some of the

main ideas in this lesson?

2 Read the text and select those words you don´t

understand. Make a list. Check your list with those

of your classmates. See how many words from your

list they know and how many you know form their

lists. Ask the teacher to explain the words whose

meaning you couldn´t find.

3 Read the text again. Summarize the main ideas.

Prepare some questions for your classmates. Ask

them your questions and, in turn, answer theirs.

Make a group of 3 or 4 and prepare a final outline of

the lesson.

4 UP TO THE CHALLENGE

The challenge that SLLs pose for the Spanish

educational system may have a working answer in

blended learning. The present point gives a detailed

account of our own LMS.

First, these tasks often include recordings of

academic Spanish together with listening

comprehension questions, which help SLLs learn

skills such as listening for the gist. The activities

offer advance organizers so that SLLs can establish

a connection between background knowledge and

the new information they are receiving. Second,

some of these tasks involve working cooperatively

with several native speakers so that SLLs are forced

to seek information and answer questions in

Spanish. Next, interactive tasks within an LMS can

be done outside the limited framework of school

time because they are open and ready to be used

24/365 days a year. As some of these kids do not

have a computer at home, the school kept the

computer room open and supervised at certain

scheduled periods. Finally, these tasks are divided

into levels so that each student can get the one which

best suits his or her capabilities.

In our case, organization was of paramount

importance ever since there had to be a perfect

synchronicity between face-to-face interaction and

on-line delivery. Every learning object we devised

for the platform had to answer one or more of the

following questions (Koper, R., 2003:7):

1. What does a person or group learn

(knowledge, competencies, skills, insight, attitudes,

intentional behavior) and in which domain?

2. What kinds of activities must be carried out to

learn? For example: observing, describing,

analyzing, experiencing, studying, problem solving,

experimenting, predicting, practicing, exploring and

answering questions.

3. How should a learning situation be arranged

(context, which people, which objects) and what

relationship does the situation have to the teaching-

learning process?

4. To what extent are the components of the

situation present externally and to what extent are

they represented cognitively-internally?

5. How, precisely, do the learning and transfer

processes occur?

6. How is motivation stimulated?

7. How is the learning result captured?

8. How should activities be stimulated?

Over the years we have been involved in CLIL

(Content and Language Integrated Learning) activity

courses for learners of English and indeed our

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

92

learning objects, we felt, had to be devised in this

way; that is, all of the contrived learning events

incorporated the contents taught in the mainstream

classes with a bias towards language acquisition.

Timing and organization was crucial as anyone can

imagine. The idea was to go one step in ahead of

ordinary face-to-face classes in order that these

students had an idea of what was going on in the

class and prepare adequate questions which would

enhance their efficiency both in the Spanish

language and in the subject they were being taught.

The weight was naturally laid on the Spanish

language and, as the year’s course wore on, there

was a shift of emphasis from language to content

learning. By and by their competence in the

classroom increased and so did their confidence in

Spanish; consequently the relationship with their

classmates also improved. After the first two weeks

of training thus, some were over the moon with

exhilaration and were really looking forward to the

next unit; whereas only a month before they had

been haggard, sluggish and discouraged. Seldom

have we seen students look forward to the

welcoming reprise of activities in the learning

system.

Our activities fulfill all of the precepts described

by Merrill (2003: 66): "… the most effective

learning products or environments are those that are

problem-centered and involve the student in four

distinct phases of learning: (1) activation of prior

experience, (2) demonstration of skill, (3)

application of skill and (4) integration of these skills

into real-world activities". On the whole our pre-

lesson activities result in a pick-and-mix of the

models described by Margaret Driscoll (2003: 30)

for blended learning, wrought with the exclusive

tools and resources provided by the LMS or those

“authoring tools” or SCORM compliant programs

integrated in it:

1. To combine or mix modes of web-based

technology (e.g., live virtual classroom, self-paced

instruction, collaborative learning, streaming video,

audio, and text) to accomplish an educational goal.

2. To combine various pedagogical approaches

(e.g., constructivism, behaviorism, cognitivism) to

produce an optimal learning outcome with or

without instructional technology.

3. To combine any form of instructional

technology (e.g., videotape, CD-ROM, web-based

training, film) with face-to-face instructor-led

training.

4. To mix or combine instructional technology

with actual job tasks in order to create a harmonious

effect of learning and working.

Every one of our units took to this learning

scenario with activities deftly crafted and carefully

planned:

1. Vocabulary.

2. Grammar.

3. CLIL.

4. Summary.

Different activities or “learning objects” (Arcos,

F., Ortega, P., Amilburu A., 2007: 2) were

implemented to be included underneath our four

headings, and summarized here:

- Comprehension exercises made from

audio or video clips.

- Comprehension exercises made from texts.

- Dictations.

- Grammatical and lexical exercises.

- Rephrasing and rewriting exercises.

- Essay writing (assignments and workshops

in Moodle).

- Write glossaries for the subjects (activity

in Moodle).

- Digital stories (handed in and assessed

through Workshops in Moodle)

- Create a FAQ for each subject.

- Have a “useful links” sections to be used

in the classroom (Spanish newspapers,

magazines, dictionaries, etc.).

5 CONCLUSIONS

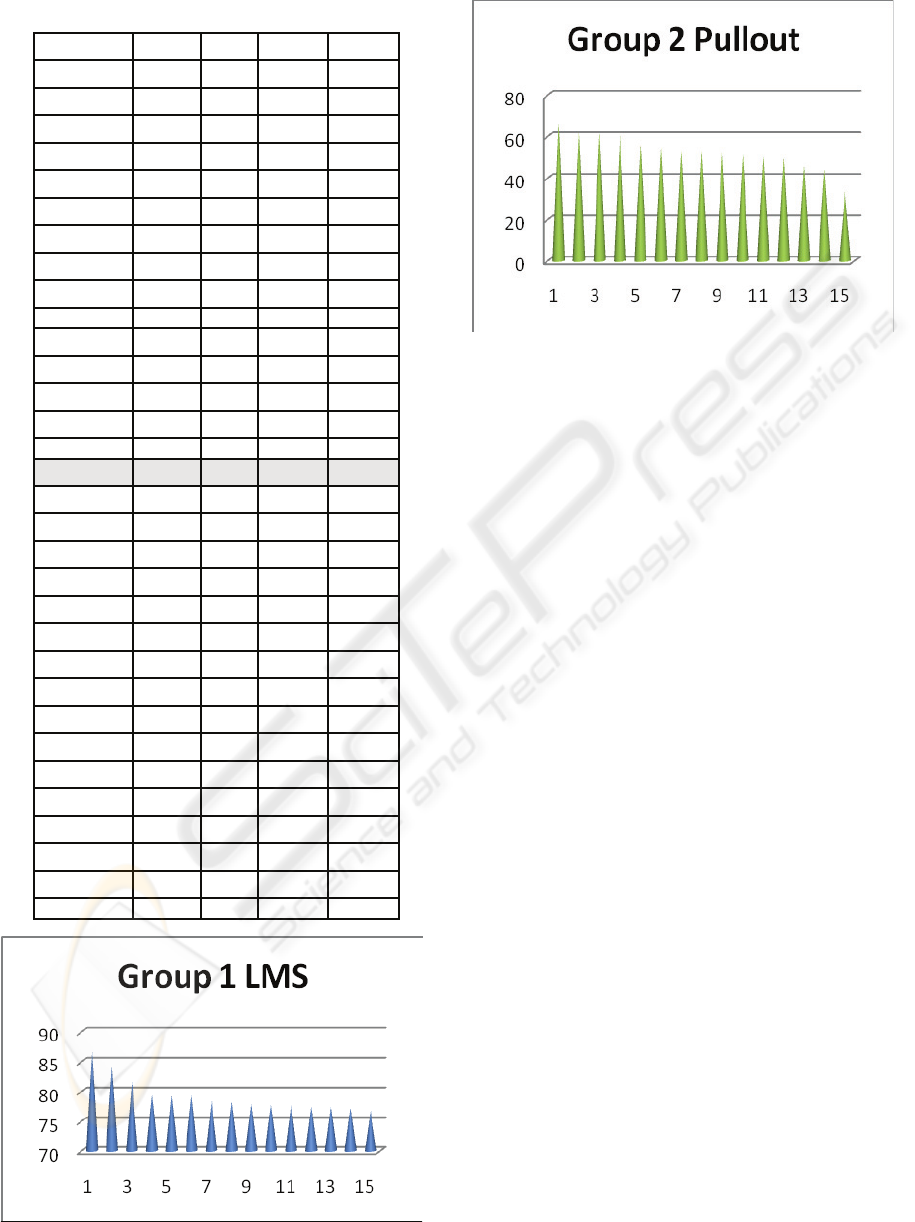

As explained at the beginning, in order to assess the

results of our project accurately, 15 SLLs were

included in it, while another group of 15 SLLs kept

on doing the traditional immersion program. Table 1

offers a register of some of the tasks both groups

did, with individual marks and averages for

comparison. The marks range from 0 to 100, the

latter equivalent to perfection. Nine lessons were

covered, each including between 10 and 14 tasks.

Data for the first three (columns L1, L2, L3) and the

total average (column (AVG) are given. It should be

pointed out that all the exercises were done and

improved in the group that used the LMS (data was

collected in the “grades” module) whereas not

everybody handed in the exercises in the other

pullout group. This was either because they didn’t

do it, or because they missed out a class that day and

did not have the opportunity to hand it in later. Also,

they did not have the chance of improving the mark

by doing it again; something the students who used

the LMS had. Diagrams showing the performance of

both groups are also enclosed below.

HOW BLENDED LEARNING CLOSES THE LANGUAGE GAP BETWEEN NATIVE STUDENTS AND SPANISH

LANGUAGE LEARNERS

93

Table 1:Results of both groups compared.

Group 1 L1 L2 L 3 AVG

Student A

88.44 68.98 81.85 86.58

Student B

85.03 63.84 84.74 84.19

Student C

87.96 64.58 90.31 81.54

Student D

84.4 64.33 85.42 79.42

Student E

88.26 53.58 92.83 79.28

Student F

91.34 54.69 73.31 79.27

Student G

86.71 58.41 80.33 78.47

Student H

87.76 59.98 94.66 78.25

Student I

83.12 60.69 77.64 77.8

Student J

85.98 60.84 86.58 77.7

Student K

81.21 64.62

81.51

77.69

Student L

89.69 57.79

79.74

77.38

Student M

76.53 65.44

77.6

77.36

Student N

86.09 56.19

74.87

77.18

Student O

85.87 61.09 88.95 76.86

Group 2 L1 L2 L 3 AVG

Student 1

67.64 55.34

61

66.59

Student 2

61.1 63.81

98.6

61.97

Student 3

67.64 52.22

54.1

61.85

Student 4

62.82 40

38.5

61.23

Student 5

80.24 39.66

32.67

56.17

Student 6

65.86 29.38

73.13

54.77

Student 7

78.22 36.69

63.5

52.91

Student 8

63.84 37.36

93.35

52.84

Student 9

35.65 43.14

40.56

52.04

Student 10

79 36.41

75.48

51.29

Student 11

67.88 33.97

35.55

50.31

Student 12

59.61 47.86

69.74

49.88

Student 13

35.26 41.83

22.99

46.05

Student 14

45.26 61.48

58.37

44.39

Student 15

48.94 60.5 58.5 33.61

Figure 1: Averages for the LMS group in fifteen tasks.

Figure 2: Averages for the Pullout group in fifteen tasks.

After analyzing the enclosed figures, it was agreed

by all parts involved that the first group have

progressed further and faster than the second one.

We talked to teachers and students, who mostly

expressed their favourable opinions of the Moodle

platform. Teachers said that tasks were finely tuned

to the actual students’ needs and thus clearly helped

them improve their language skills. Ample

opportunities for using academic language in

relevant contexts were provided. They added that

some of the students have revealed themselves as

adroit language users, something they didn’t expect

judging from their experiences in previous years.

The LMS had been received with a certain degree of

reticence, as it usually happens with new tools.

Then, there is the fact that starting off is always

hard: the LMS took a lot of time and effort for

something which they saw, at its best, as an

uncertain promise. However, at the end of the

project, they all considered that the LMS had given

much better results than they had expected. One of

them exclaimed: “Not even in my wildest dreams

did I ever anticipate such fruitful achievement!”

As for the students, they felt grateful and proud at a

time. On the one hand, they were vividly conscious

of their progress, something which boosted their

self-esteem and which made them thank their

teachers once and again. On the other, they took a

more active role in mainstream subjects thanks to

their new language confidence. They expressed their

wish to keep on moving ahead, and now dreamt of…

who knows, maybe even university. Even their

parents came to the school and overwhelmed

teachers with their gratitude, having the impression

that their children were now making their own way.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

94

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the help and involvement of both

teachers and students at Fray Ignacio Barrachina

Secondary School in Ibi (Alicante).

REFERENCES

Arcos, F., Amilburu, A., and Ortega, P. (2007) Un nuevo

modelo de instrucción en la enseñanza del idioma a

través del aprendizaje mixto (Blended Learning). In

Merma Molina, G., et alter (Coords.) Aportaciones

curriculares para la interacción en el aprendizaje,

Marfil: Alicante.

Driscoll, M. (2004) Blended Learning: Let’s Get Beyond

the Hype, IBM Global Services: New York.

España: Organic Law of Education. (2007). Madrid:

Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

Hill, J.D. and Flynn, K.M. (2006) Classroom Instruction

That Works With English Language Learners,

Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Krashen, S. D. and Terrell, T. D. (1983) The natural

approach: Language acquisition in the classroom,

Hayward, CA: Alemany Press.

Koper, R., and Van Es, R. (2004) Modeling units of

learning from a pedagogical perspective. In R.

McGreal (Ed.) Online education using learning

objects, London: Routledge Falmer.

Merrill, M.D. (1994) Instructional Design Theory,

Englewood Cliffs: Educational Technology

Publications.

Nieto, S. (2002) Language, culture, and teaching: Critical

perspectives for a new century, Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Omaggio, A. (1986) Teaching Language in Context,

Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Ortega, P., and Arcos, F. (2008) ‘How e-homework can

solve the homework debate in primary schools’,

ENMA2008. International Conference on Engineering

and Mathematics, pgs 5-10. Bilbao: Kopiak.

Ortega, P., and Arcos, F. (2009a) ‘How can Moodle help

Struggling students?’ EDULEARN2009. International

Conference on Education and New Learning

Technologies, pp. 2337-2340.

Ortega, P., and Arcos, F. (2009b) ‘Blended learning: an

efficient response to some of the problems raised by

youths at risk’, INTED2009. International Technology,

Education and Development Conference, pp. 637-642.

Ortega, P., and Arcos, F. (2009c) ‘CLIL enhanced through

digital storytelling’, ENMA2009. International

Conference on Engineering and Mathematics, pgs

228-231. Bilbao: Kopiak.

Ortega, P., and Arcos, F. (2009d) ‘Moodle applied within

a special needs classroom’, IASE 2009, 11

th

Biennial

Conference, pp.204-207.

Ortega, P., and Arcos, F. (2009e) ‘Zeroing in on truancy:

the use of blended learning to keep truants in the

classroom’, IATED 2009, pp. 288-291.

HOW BLENDED LEARNING CLOSES THE LANGUAGE GAP BETWEEN NATIVE STUDENTS AND SPANISH

LANGUAGE LEARNERS

95