LEARNER’S ACCEPTANCE BASED ON SHACKELL’S

USABILITY MODEL FOR SUPPLEMENTARY MOBILE

LEARNING OF AN ENGLISH COURSE

Mohssen M. Alabbadi

Computers and Electronics Institute (CERI), King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST)

P.O.Box 6086, Riyadh – 11442, Saudi Arabia

Keywords: Mobile Learning (m-learning or mLearning), Usability, Shackel’s Usability, Technology Acceptance Model

(TAM), English as a Second Language (ESL), English as a Foreign Language (EFL), Mobile Assisted

Language Learning (MALL).

Abstract: The use of mobile phones to facilitate the learning process, the so-called mobile learning (m-learning or

mLearning), raises various issues, thus making it critical to study the learner adoption and acceptance of

mLearning. In this research, a supplementary instructional materials, supporting a regular classroom (i.e.,

face-to-face) of English as second language (ESL) course, called MobiEnglish, are developed and

implemented, using ready-made commercial products and tools. MobiEnglish, delivered through mobile

phones, provides different modes of interactions between the content, students, and instructor. A survey

method, employing questionnaire, is used to collect learners' responses. The questionnaire contains 19 items

based on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” to measure the four

constructs of Shackel’s usability model (i.e., effectiveness, learnability, flexibility, and attitude). The results

of responses show high acceptance level of MobiEnglish, reflecting the potential of using mLearning in

teaching ESL. Furthermore, the research reveals that the use of the enhanced features of mobile computing

with respect to multimedia (i.e., voice and video) is more appealing to learners of ESL.

1 INTRODUCTION

These days information and communication

technologies (ICT) are becoming more mobile and

ubiquitous. The lowering cost of mobile devices and

the availability of wireless infrastructures are

radically transforming the way people access and

utilize information resources. The “anytime and

anywhere” has evolved as a new paradigm to

establish a new dimension for providing services

such as mobile commerce (mCommerce), mobile

business (mBusiness), etc.

The new paradigm has powerful features and

functions such as mobility, reachability, localization,

flexibility, and motivational effects due to self

controlling and better use of spare time. This opens

opportunities in the learning environment, with of

course, some challenges and questions, creating

“mobile learning,” m-learning or mLearning for

short, with expected benefits to be reflected in more

efficient and improved learning results.

Mobile learning can be defined as any service or

facility that supply a learner with general electronic

information and educational content that aids in the

acquisition of knowledge regardless of location and

time (Lehner, 2002), using mobile handheld devices,

while the learner and/or the learning material

providers could be on the move. Mobile learning is

the intersection of mobile computing and e-learning,

conveying e-learning through mobile devices using

wireless connectivity (Milrad, 2003, Stone, 2007).

Mobile learning has raised various issues, in

particular the user interface, which plays an

important role toward the implementation of

mLearning. Mobile devices, in general, have some

weaknesses: very small screen displays, low

resolution, low processing power, restricted input

capabilities of some of these devices, and limited

storage capability, making the viability of mobile

technology in learning questionable. Therefore, it is

critical to study the learner adoption and acceptance

of mLearning.

121

M. Alabbadi M. (2010).

LEARNER’S ACCEPTANCE BASED ON SHACKELL’S USABILITY MODEL FOR SUPPLEMENTARY MOBILE LEARNING OF AN ENGLISH COURSE.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 121-128

DOI: 10.5220/0002810101210128

Copyright

c

SciTePress

In this research, we study the acceptance of learners

of supplementary instructional materials for a

regular classroom of English as a Second Language

(ESL) course, also called English as a Foreign

Language course (EFL). The supplementary

materials are delivered through their mobile phones.

In contrast to present mLearning systems for

teaching ESL, which support mostly static, non-

interactive content, where the learners can only

listen and view content, this mobile learning system,

called MobiEnglish, provides different modes of

interactions between the material, students, and

instructor.. MobiEnglish uses ready-made

commercial products and tools from Hot Lava

Software, namely the Learning Mobile Authoring

(LMA) and the Mobile Delivery and Tracking

System (MDTS).

The acceptance of learners is measured using

Shackel’s usability model, consisting of four

constructs: effectiveness, learnability, flexibility, and

attitude. A survey method, employing

questionnaires, is used to collect learners' responses.

The structure of the rest of this paper is as

follows. Section 2 describes MobiEnglish, whereas

Section 3 explains Shackel’s usability model.

Section 4 specifies the experiment environment and

the methodology of the study is described in Section

5, followed by analysis of the results in Section 6.

Finally, the concluding remarks are provided in

Section 7.

2 MOBILE LEARNING FOR ESL

2.1 Literature Review

Mobile learning has been used for teaching ESL, in

particular for teaching English language words. A

mobile learning system, called Mobile Learning

Tool (MOLT), was developed at Near East

University, Nicosia, Cyprus, where short message

service (SMS) messages, containing new technical

English language words with and their meanings, are

sent to the students throughout the day in half-hour

intervals; MOLT was tested on 45 first-year

undergraduate students with successful results,

where their learning abilities were assessed by

performing tests before and after the experiment

(Cavus, 2008). In a Turkish university, in order to

improve English language learners' vocabulary

acquisition, instructional materials were developed

to be delivered through mobile phones operated in

second generation GSM technology using

multimedia messages (MMS), which allowed the

students to see the definitions of words, example

sentences, related visual representations, and

pronunciations; after the students finished reading

the MMS messages, interactive SMS quizzes for

testing their learning were sent, where the questions

were multiple-choice questions, selected at random

from a pool of questions, and the students send their

answers to the system via their mobile phones

(Saran, 2008).

As learning, in general, demands more

personalised and contextualised access to learning

resources, PALLAS, a prototype system for mobile

language learning, which can be used for teaching

ESL, considers dynamic and static parameters,

where the dynamic parameters (e.g., location, time,

and the mobile device) are updated automatically by

the system and the static parameters (e.g., name, age,

gender, native language, and leisure time) are

provided manually by the learner (Petersen, 2008).

2.2 Requirements of mLearning for

Teaching ESL

Most learners of ESL consider ESL as ‘the gate’ to

higher education, employment, economic prosperity,

and social status, where learners have to perform

well in various English tests in order to pass the

“gate,” limiting teachers of ESL to provide a truly

authentic teaching environment. Therefore, the main

purpose of learning English, in the learners' minds,

is to pass the exams, where the learners are asked to

memorize new words or phrases, become familiar

with grammatical exercises, and to make sure that

they can do well in all kinds of standardized tests,

resulting that most students cannot communicate

fluently in English and they have trouble distinctly

expressing themselves (Cui, 2008).

It is thus important to create a mobile learning

system to support teaching ESL not only for

teaching new words, but more as an educational

tool, thus contributing to the motivation and success

of learners. In particular, the emphasis should be

toward developing listening, speaking, and reading

skills, with the possibilities for both synchronous

and asynchronous interaction. Mobile multimedia

content can create a rich learning environment that is

particularly suited to the teaching of second and

foreign languages. At present, mLearning systems

for ESL support mostly static, non-interactive

content, where learners can listen and view content,

but not do much more. Using current capabilities of

mobile computing, a variety of content can be

developed for language learning, including (Collins,

2005):

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

122

• Short dialogs as conversational models;

• Recorded audio stories with the ability to

follow along with the printed text while listening to

develop both listening and reading skills;

• Picture dictionaries with illustrations of

common objects and actions, plus audio playback of

the new language and translations into learners’

languages;

• Preparation for tests such as TOEFL;

• Greater interactivity with the content, through

the ability to submit student responses;

• Access to teachers and libraries; and

• Ability to interact with other learners, including

playing games, conversation, and project-based

learning, preferably using the phones’ capabilities to

take pictures, capture sound, and input text.

2.3 MobiEnglish

MobiEnglish is a mobile learning system, providing

supplementary instructional material to support

regular face-to-face classroom course for teaching

ESL. MobiEnglish provides “anytime and

anywhere” resources, rich interaction, powerful

support for effective learning, and performance-

based assessment. In addition, it is designed to

produce support, motivation, continuity, alerts,

introductions, tips, revision, and study guides.

MobiEnglish uses ready-made commercial

products and tools from Hot Lava Software, namely

the Learning Mobile Authoring (LMA) and the

Mobile Delivery and Tracking System (MDTS). The

LMA enables the instructors and teachers to create,

customize, review, and update their own interactive

supplementary content (i.e., text, images, audio, and

video). MDTS, on the other hand, is a WAP-based

environment, having a database of the names and

mobile phone numbers of the learners for delivery

and management of learning materials.

MobiEnglish is designed to have three modes of

operation: offline mode, where the learning material

is downloaded into the learner's handheld device;

online mode, where the learner interacts with the

learning material online; and hybrid mode, where

some of the learning material is downloaded into the

learner's handheld device but some are to be

interacted online. Each mode has its own

pedagogical values. The offline mode, however,

allows the learner to interact with the learning

material any number of times, as desired by the

learner, without incurring any additional cost on the

learner, other than, of course, the initial airtime cost

for downloading the learning material. When the

online or hybrid modes are used, MobiEnglish

provides very effective learning tool by tracking the

progress of learners and supplies the instructors with

statistical reports about the learners such as their

duration of usage, scores on the quizzes and tests,

weakness points, etc.

The supplementary material is structured into

modules, where the instructor specifies the number

of the modules and the delivery time for each

module. The content of each module is developed

using LMA. Upon receiving an SMS message, sent

automatically from MDTS, on the learner's mobile

phone, the learner simply click on the link provided

on the SMS to download the lesson content or to

interact with lesson, depending on the usage mode of

MobiEnglish.

There are three categories of modules: basic,

which contains definitions of some of the words,

usage examples of the defined words, and a quiz of

multiple-choice questions; enhanced, which contains

an audio conversation, a transcript of the

conversation, definitions of some of the words used

in the conversation, usage examples of the defined

words, and a quiz; advanced, which contains a video

clip, a transcript of the conversation, definitions of

some of the words used in the conversation, usage

examples of the defined words, and a quiz. Figure 1

shows snap shot of some screens of MobiEnglish.

In MobiEnglish, the quizzes and tests are

multiple-choice questions. But it has the capability

for blank filling questions. For multiple-choice

questions, MobiEnglish can automatically feedback

the correct answers to the learners, as specified by

the instructor of the course, after some number of

trials, specified by the instructor. However, when

MobiEnglish is used in the online mode, the learner

performance on the quizzes or tests can be recorded

to be examined by the instructors, thus extending the

learner-content interaction into instructor-learner

interaction.

3 SHACKEL'S USABILITY

MODEL

In general, usability (or functionality) refers to the

suitability of a product to its intended use, where a

product is used in the general sense to mean a d to

make the use of a product possible or to support or

to restrict its use. Therefore, the concept of usability

was explicitly defined in the literature, preparing the

ground for the usability measurements.

LEARNER'S ACCEPTANCE BASED ON SHACKELL'S USABILITY MODEL FOR SUPPLEMENTARY MOBILE

LEARNING OF AN ENGLISH COURSE

123

Figure 1: Snap shots of some MobiEnglish screens.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

124

The learning system, where the content is agreed by

consulting and to be modified by the learner, falls

into the class of “interactive product” (Keinone,

1999). The existing characteristics of this type of

products cannot wholly predict its usability, because

the responsibility of getting the product to work is

shared; it depends not only on the qualities of the

product, but on its user as well. When an interactive

product gives less than its optimal service, this could

be because of its bad design, faulty product, an

incompetent user, or the fact that the wrong kind of

product has been selected for this user. All these

possible reasons have to be investigated before

decision about the usability of the interactive

product is given. In general, the number of important

aspects to measure usability of an interactive product

is greater than of other type of products. However,

there are several types of criteria that are common to

all types of products.

There are three approaches to measure usability:

Shackel's approach (Shackel, 1991, Chapanis, 1991,

Nielsen's approach (Nielson, 1994), and ISO 924-

part 11 (International Organization for

Standardization, 1998). These approaches measure

usability at an operational level, considering

usability objectives and establishing relationship

between usability, utility, acceptance, and affect to

the interaction.

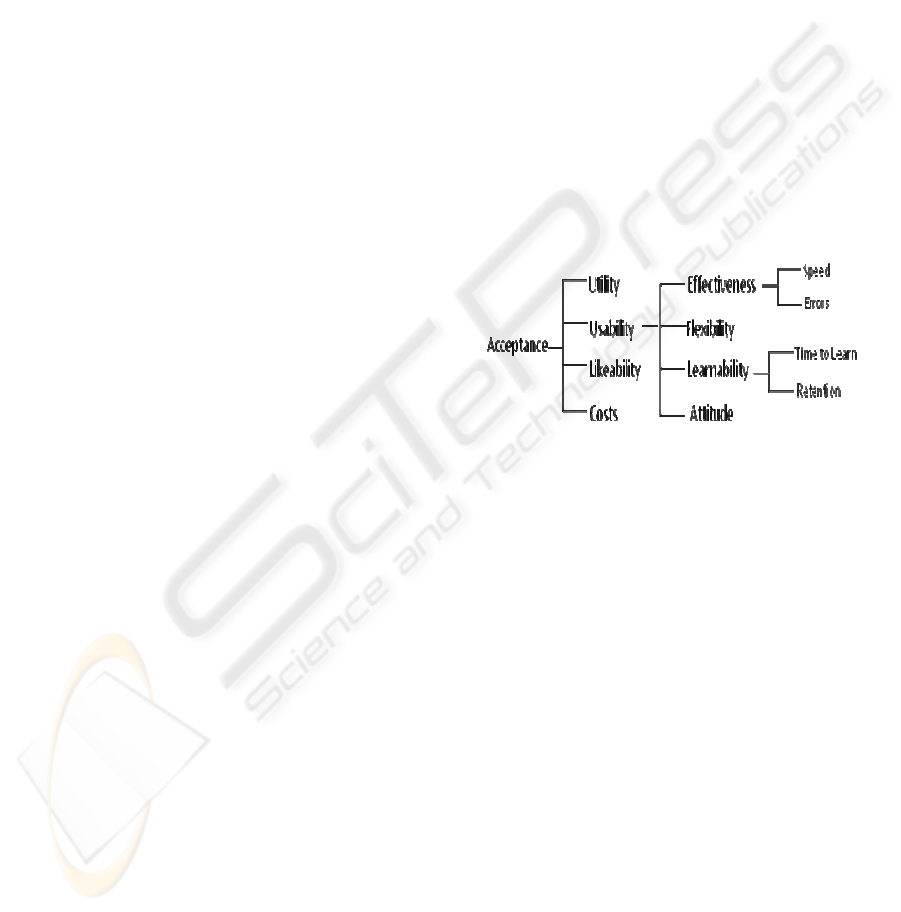

Shackel's idea of usability joins usability to other

product attributes and higher level concepts. Shackel

viewed usability from product perception model,

where acceptance is the highest level concept.

Thus, acceptance is a function of perceived utility,

usability, likeability, and costs.

Utility refers to the match between user needs

and product functionality, while usability refers to

the ability of the user to utilize the functionality in

practice. Likeability refers to affective evaluations,

and costs include financial costs as well as social

and organizational consequences. Having located

usability in the context of acceptance, Shackel

presents a descriptive definition of usability as:

“Usability of a system or equipment is the capability

in human functional terms to be used easily and

effectively by the specified range of users, given

specified training and user support, to fulfill the

specified range of tasks, within the specified range

of environmental scenarios” (Shackel, 1991).

Shackel’s usability model is the most suitable

measure the acceptance of learners for this

environment, since it considers usability to be an

aspect that influences product acceptance. Indeed

according to Shackel’s model, usability is a property

of a system or a piece of equipment; the property is

not constant but being relative in relation to the

users, their training and support, task, and

environments. Usability has two sides, one related to

subjective perception of the product and the other to

objective measures of the interaction.

According to Shackel’s usability model, for a

system to be usable, it has to achieve defined levels

on the following constructs (Shackel, 1991):

◊ Effectiveness: It considers the results of

interaction in terms of speed and errors.

◊ Learnability: It refers to the relation of

performance to training and frequency of use, i.e.,

the novice user's learning time with specified

training and retention on the part of casual users.

◊ Flexibility: It refers to the degree of adaptation

to tasks and environments beyond those first

specified; and

◊ Attitude: It refers to the acceptable levels of

human activities in terms of tiredness, discomfort,

frustration, and personal effort.

Figure 2: Constructs of Shackel's Usability Model.

4 THE EXPERIMENT

An experiment was conducted on an ESL class,

offered at an English language institute, where the

class was selected randomly across the available

classes at the period of the experiment. The duration

of the experiment is 7 weeks, divided into 4 periods;

the first three periods consist of two weeks, whereas

the last period lasted for one week only. Table 1

shows the number of learners and the mode of use

for each period. The contents of MobiEnglish,

however, were all specified by the instructors of the

courses, where the learners in all the periods

received two lessons per week.

In the hybrid mode, the learner answers the quiz

online, whereas in the offline mode, the learner is

automatically given the correct answers to the quiz

questions, after two trails by the learner. In the

hybrid mode, the learner can perform the quiz only

once with the correct answers fed back automatically

after answering each question.

LEARNER'S ACCEPTANCE BASED ON SHACKELL'S USABILITY MODEL FOR SUPPLEMENTARY MOBILE

LEARNING OF AN ENGLISH COURSE

125

Table 1: Number of learners and usage characteristics of

MobiEnglish for each period.

Period #1 #2 #3 #4

# of learners 20 9 9 9

Category of

Content

B E A A

Mode of Usage O O O H

B: Basic; E=Enhanced; A=Advanced

O=Offline; H=Hybrid

5 METHODOLGY OF THE

STUDY

This study employed a survey method, using a

questionnaire to determine the learners' acceptance

of MobiEnglish. The questionnaire has been adapted

from Shackle’s questionnaire, where some changes

were applied to suit the need of this study.

The questionnaire contains 20 items based on a

5-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly

Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” The response that

indicates the lowest approval (i.e., “Strongly

Disagree”) received a score of 1, with an increase of

1 point for each response (i.e., 2 points for

“Disagree,” 3 points for “Neutral,” 4 points for

“Agree,”) until the response that indicates the

greatest approval (i.e., “Strongly Agree”) received a

score of 5. Therefore, the maximum score of this

instrument is 5*19=120 and the minimum score is

19.

MobiEnglish has the capability to make the

learners fill the questionnaires through their mobile

phones. But it was decided to use traditional

methods because the intended purpose of the project

is to study the acceptance of mLearning to support

teaching. The acceptance of users to perform

surveys using mLearning should be treated

separately.

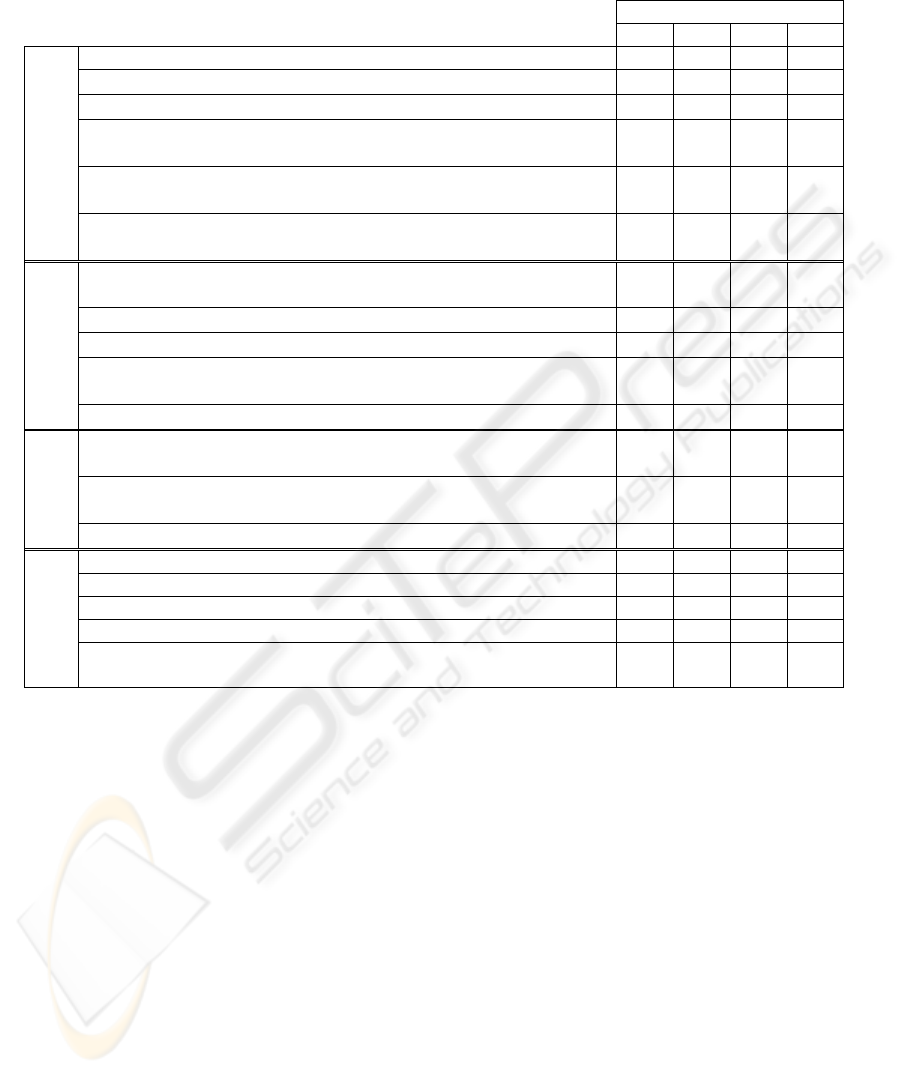

6 ANALYSIS OF THE RESULS

Data gathered on this questionnaire were coded in

SPSS for analysis purposes. The responses of the

learners to the questionnaires are summarized in the

table given in the Appendix.

As it is clearly shown in the table, the learners'

acceptance MobiEnglish is very high, where most

responses score more than 4, implying “Agree.” For

most of the questions, the scores of responses

increase as moving from period 1 to period 4, with

some instances where period 4 is lower than period

3; this indicates the increasing level of acceptance of

system as the system is used more. Furthermore, this

shows the Advanced modules, containing

multimedia features (i.e., voice and video), is more

appealing to learners.

There are two questions, where their responses

came out to be lower than 4 for all the periods; the

first question is “I was able to download the learning

material without errors” and the second one is

“There was too little information to be read, before I

can use this mobile learning system.” For the first

question, the low score in responses could be due to

network availability and performance because the

score of responses for downloading the Advanced

module, containing video, is larger than the score of

responses for downloading the Enhanced, containing

audio, and the Basic module, containing only text.

For the second question, the responses reflect the

user guides mentality of users; even though most

systems, either hardware or software systems, come

with user guides that are seldom used by users.

Therefore, users anticipate having some information

to come with the system. This comes clear when we

consider the responses to the question “It was easy

to learn to use this mobile learning system.” For this

question, the score of responses came out to be

greater than 4.2.

7 CONCLUSIONS

MobiEnglish has received high acceptance level

with respect to Shackle’s usability model. This

reflects the potential of using mLearning in teaching

foreign languages, in general, and in teaching

English, in particular. Furthermore, using the

enhanced features of mobile computing with respect

to multimedia (i.e., voice and video) is more

appealing to learners of ESL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The experiment has been conducted at the premises

of Direct English Center of Al Khaleej Training and

Education Company in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The

authors would like to thank Al Khaleej Training and

Education Company. In addition, special thanks are

due to Elite Network and Mr. Hasan Alabbadi, for

their support and feedback.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

126

REFERENCES

Cavus, N. and Ibrahim, D., 2008. MOLT: A Mobile

Learning Tool That Makes Learning New Technical

English Language Words Enjoyable. International

Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM),

Volume 2, No 4. (Retrieved on Jan. 14, 2010,

required registration, at URL: http://online-

journals.org/i-jim/article/view/530/613).

Chapanis, A., 1991. Evaluating usability. In Shackel, B.

and Richardson, S. (Eds.), Human Factors for

Informatics Usability, pp. 359-398, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Collins, T., 2005. English Class on the Air: Mobile

Language Learning with Cell Phones. In the

Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Conference

on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT’05), July

5-8, 2005, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. IEEE Computer

Society.

Cui, G. and Wang, S., 2008. Adopting Cell Phones in EFL

Teaching and Learning. Journal of Educational

Technology Development and Exchange, Volume 1,

No. 1, November, 2008, pp. 69-80.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO),

1998. Ergonomic Requirements for Office Work with

Visual Display Terminals (VDTs) – Part 11: Guidance

on Usability. International Standard, ISO 9241-11,

First edition, March 15, 1998, Reference number ISO

9241-11:1998(E).

Keinone T., 1999. Theory of a Design Goal: Usability of

Interactive Products, (Retrieved on Jan. 14, 2010 at:

URL: http://www2.uiah.fi/projects/metodi/158.htm).

Kukulska-Hulme, A. and Shield, L., 2007.An Overview of

Mobile Assisted Language Learning: Can mobile

devices support collaborative practice in speaking and

listening. EUROCALL 2007: Mastering Multimedia:

Teaching Languages Through Technology, University

of Ulster, Coleraine Campus, Northern Ireland, 5 - 8

September 2007 (Retrieved on Jan. 14, 2010, at URL:

http://vsportal2007.googlepages.com/Kukulska_Hulm

e_and_Shield_2007.pdf).

Lehner, F., Nösekabel, H., and Lehmann H. 2002.

Wireless E−Learning and Communication

Environment WELCOME at the University of

Regensburg. In Maamar, Z., Mansoor, W., and van

den Heuvel, W. (Eds.), The Proceedings of the First

International Workshop on M-Services - Concepts,

Approaches, and Tools (ISMIS'02), Lyon, France, June

26, 2002. CEUR-WS.org, CEUR Workshop

Proceedings, Vol-61. (Retrieved on Jan. 14, 2010, at

URL: http://ftp.informatik.rwth-

aachen.de/Publications/CEUR-WS/Vol-

61/paper2.pdf).

Milrad, M., 2003. Mobile Learning: Challenges,

Perspectives, and Reality. In Nyiri, K. (Ed), Mobile

Learning Essays on Philosophy, Psychology and

Education. Vienna: Passagan Verlag, pp. 151-164.

Nielson, J., 1994. Usability Engineering, Morgan

Kaufmann, San Francisco, USA.

Petersen, S. A. and Markiewicz, J-K., 2008. PALLAS:

Personalised Language Learning on Mobile Devices.

In the Proceedings the Fifth IEEE International

Conference on Wireless, Mobile and Ubiquitous

Technologies in Education (WMUTE 2008), 23-26

March 2008, Beijing, China, pp.52-59. IEEE

Computer Society.

Saran, M., Cagiltay, K. and Seferoglu, G., 2008. Use of

Mobile Phones in Language Learning: Developing

Effective Instructional Materials, In the Proceedings

of The Fifth IEEE International Conference on

Wireless, Mobile, and Ubiquitous Technology in

Education (WMUTE 2008), 23-26 March 2008,

Beijing, China, pp. 39-43. IEEE Computer Society.

Shackel, B., 1991. Usability – Context, Framework,

Design and Evaluation, In B Shackel, B. and

Richardson, S. (Eds.), Human Factors for Informatics

Usability, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

UK, pp. 21-38.

Stone, A., 2004. Designing Scalable, Effective Mobile

Learning for Multiple Technologies, In Attwell, J. and

Savill-Smith, C. (Eds.), Learning with Mobile Devices,

Learning and Skills Development Agency, London.

LEARNER'S ACCEPTANCE BASED ON SHACKELL'S USABILITY MODEL FOR SUPPLEMENTARY MOBILE

LEARNING OF AN ENGLISH COURSE

127

APPENDIX

Mean of responses

Period # 1 2 3 4

Effectiveness

I received the SMS messages as specified by the instructor. 4.1 4.8 4.8 4.8

I was able to download the learning material in reasonable time. 3.9 3.6 4.3 4.2

I was able to download the learning material without errors. 3.5 3.1 3.8 3.2

I can effectively complete my work by using this system through

my mobile phone or handheld device.

3.4 4.1 4.8 4.7

This mobile learning system has all the functions and capabilities

that I expect it to have.

3.5 4 4.1 4.3

Overall, this mobile learning system responds to my requests in

reasonable time and without errors.

3.5 3.8 4.1 4.3

Learnability

I do not need to learn a lot of things before I could use this mobile

learning system.

4 4 3.7 4

The information provided by the system was easy to understand. 4 4.7 4.6 4.7

It was easy to learn to use this mobile learning system. 4.2 4.8 4.9 4.5

There was too little information to be read, before I can use this

mobile learning system.

3.3 2.7 3.6 3.5

Overall, this mobile learning system is easy to use. 4.4 5 5 4.5

Flexibility

I was able to download the learning material at anywhere and

anytime through this system.

4.2 4.4 4.6 3.7

I was able to use the learning material at anywhere and anytime

through this system.

4 4.2 4.7 3.8

Overall, I think this mobile learning system is flexible. 4.2 4.7 4.4 4.3

Attitude

I feel comfortable using this system. 3.9 4.3 4.9 4.3

I will recommend this system to my colleague. 3.9 4.7 4.6 4.4

I enjoyed doing my task through this system. 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.5

I feel that this system is user friendly. 4.1 4.3 4.9 4.5

Overall, this mobile learning system makes it easy for me to access

the required learning material.

3.9 4.7 4.6 4.5

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

128