GET TOGETHER

A Case of ERP Implementation and its Transfer to Class

Johan Magnusson, Håkan Enquist

Centre for Business Solutions, University of Gothenburg, PO Box 605, Gothenburg, Sweden

Anders Gidlund, Bo Oskarsson

SYSteam AB, Gothenburg, Sweden

Keywords: ERP, Implementation, Education, User involvement.

Abstract: Regardless of how well designed and functioning the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system is, the

dimensioning factor for ERP utilization will be the users themselves. In this paper, we report from a case

study of a medium-sized manufacturing company that took an alternative approach to their ERP

procurement and implementation. Through involving multiple process owners in a series of workshops with

the scope of specifying the as-is and to-be process of the business, the company focused on getting the users

involved from the start. A selection of the findings in this case has been used as inspiration for a course-

module for teaching ERP, and this paper reports from the case and the transfer of experience into class.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) projects are

illustrious for going over budget, under scope and

over time (Davenport, 1998; Upton & Staats, 2008).

Gartner Group (Ganley, 2008) report that in 85% of

all the implementations, the projects failed to deliver

on time, scope and budget.

The reason for this high degree of failure can be

found in the complex nature of the projects. Through

involving both changes on the business process- as

well as the information technology (IT) side, the

projects are associated with a high risk of failure

(Aladwani, 2001; Sammon & Adam, 2010; Hakim

& Hakim, 2010).

To alleviate this high risk of failure, researchers,

consultants and professional analysts alike have

studied what they refer to as “critical success

factors” of ERP implementations. The number of

research articles within this tradition have, however,

suffered from being overly normative and at many

times devoid of empirical foundation (Hong & Kim,

2002; Kumar et al, 2003).

Regardless of this, the “common ground” when

it comes to CSFs for ERP implementations include

explicit top management support, flexibility in

additional funding, and user involvement (Ganley,

2008).

Following up on the last of these CSFs (user

involvement), we have conducted a case study of a

Swedish medium-sized manufacturing company.

After conducting the case study, we transferred the

results into the design of a course module for

teaching ERP. This course module was implemented

into the curriculum from November 2008.

Several researchers have spent a considerable

amount of time and effort in integrating ERP into the

curriculum of higher education (David et al, 2003;

Hawking et al, 2002; Hayen & Andera, 2005;

Magnusson et al, 2009; Nelson, 2002; Roseman et

al, 2001; Wixom, 2004). This article aims to

contribute to this tradition.

The purpose of this paper is to report some of the

findings of the case, together with the design of the

course module.

2 METHOD

The case was selected for the company’s successful

ERP procurement and implementation. This level of

success was based on their own assessment.

507

Magnusson J., Enquist H., Gidlund A. and Oskarsson B. (2010).

GET TOGETHER - A Case of ERP Implementation and its Transfer to Class.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 507-512

DOI: 10.5220/0002866305070512

Copyright

c

SciTePress

The company (Hestra Inredning AB, Hestra) is a

medium.sized, family-owned manufactory company.

Being formed in 1900, it is one of Scandinavia’s

leading actors within the shop-fitting sector.

The case study involved a short pre-study where

respondents in the form of one consultant and one

representative of the company were approached to

give introductory information and potential access to

the company.

After this, on-site interviews with five

representatives of the company followed. The

interviews were semi-structured and took

approximately one hour to conduct. The interviews

were sound-recorded and fragments that were

regarded to be of particular interest to the

researchers were transcribed.

Following this, a short description of how the

company went about with their procurement and

implementation was constructed, and this

description was sent back to the respondents for

feedback. After taking the feedback into account and

altering the description, the researchers continued to

transform the case into a methodology for teaching

ERP. This resulted in a course module that was

implemented for the first time in 2008.

3 THE CASE OF HESTRA

In the fall of 2005, the Chief Financial Officer of

Hestra was at wits end in regards to what the

company should do with their current ERP system.

The current system (Intentia (Lawson) Movex) had

been installed in 1998, and had since proved to be

difficult to manage and in dire need of an upgrade.

After a brief analysis of what the costs of the

necessary upgrade would be, an alternative plan was

set into effect.

The company’s idea was to investigate the pre-

requisites for the procurement of a new ERP system.

After initial discussions with a local consulting firm,

the idea arose that any steps towards a new ERP

system would require a thorough analysis of the

current operations.

Hestra was currently organized in a process

oriented manner. For Hestra, this entailed having

organized their operations into production-related

and supporting processes, and with individual co-

workers assigned roles of process-owners.

The process-oriented approach was initiated as

an effect of demands from the customer side, where

Hestra had to comply with environmental standards

in order to maintain their Tier 1 status. This involved

adhering to process standards such as ISO9000 and

ISO14000, which put a strong emphasis on the link

between documentation and the current (factual)

process configuration.

Even though Hestra had been working for quite

some time in a process-oriented manner, there was a

lack of overall business understanding. The process

owners were well adept and fully in tune with their

individual processes, yet after a short evaluation in

December 2005, it quickly became apparent that the

hand-off between the different processes was not

explicitly known.

3.1 Mapping the Processes

In June 2006, the sub-process owners were brought

together to specify the as-is and the to-be processes.

The idea behind this was that a large portion of the

benefits of the ERP implementation would become

visible in the hand-offs between the different sub-

processes, and not only through making the sub-

processes themselves more efficient.

Hence, a series of workshops were held where

the sub-process owners were asked to describe their

processes to the rest of the owners. This was

intended to awaken discussion in regards to how the

process was configured and what possible issues

could be found in the current configuration.

In retrospect, the sub-process owners all saw this

as somewhat of a break-through for operations.

Previously, they had been highly adept in their own

process, yet at the same time they were unaware of

what the implications of hybrid routines and

improvisation would be for the activities further

down the stream.

This series of workshops resulted in a higher

joint understanding and common ground in regards

to what the business process really was at Hestra.

All the participants in the workshops were given a

heightened understanding of how value was created

at Hestra. At the same time, they reported a higher

level of involvement in the daily operations, along

with a strong will to work for constant process

improvement.

The explicit results of the workshops were

process maps of the five key processes for Hestra.

This collection of process maps was then handed

over to three previously selected ERP system

vendors (Lawson, Microsoft and Jeeves) as the main

part of the requirements specification.

3.2 Procurement and Implementation

The instructions for the ERP vendors was that they

should show how their product would be able to

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

508

support the five identified processes according to the

specified configuration. This was done in the form

of a series of workshops where the vendors

demonstrated their products directly in the

processes.

Out of the short-listed vendors, only one was

seen as complying with the requirements specified

by Hestra. This was due to that the bulk of vendors

stuck to a traditional functional description of what

the ERP system could do, and did not amply respond

to the process oriented requirement specification.

By early fall of 2006, an agreement was reached

between Hestra and one of the ERP vendors. Since

the sub-process owners had been so involved in the

requirements specification, the next step was to

assign them the roles of power-users in the new

system.

This involved increasing the product specific

knowledge of the sub-process owners so that they

would be able to assist in the roll-out of the new

system. The training was conducted between

February and June 2007, and one of the outcomes of

this was a unique set of training material and user

instructions for Hestra.

Since the sub-process owners were well adept

with both the processes and the system, they were

asked to take over the creation of user instructions.

This was seen as an important step to avoid any

lock-in and dependency of external consultants.

The ERP system was put into operations in

December 2007, after a continuous and automatic

conversion of the necessary posts and master data.

This entailed that the new system was run in the

background, with the same data as the original

system. Through working with two parallel systems,

the go-live was not a traditional go-live with all the

associated risks, but rather a shut-down of the old

system and a continued operations in the new. This

resulted in the switch being almost completely free

from the traditional problems and risks.

3.3 Transferring the Experience into

an Educational Setting

After going through the case of Hestra, a group of

consultants and lecturers started to exchange ideas

about if and how some of the experiences made

could be transferred over to an educational setting.

It quickly became apparent that the lessons

learned from Hestra could be transferred into

courses involving elements of ERP training. After

careful consideration, the group arrived at the

following list of assumptions for integrating the

lessons learned from Hestra into a course module for

ERP education:

A process-oriented approach could be used to

shift the pedagogical focus from technical

exercises to an increased understanding of the

business and the integrated nature of ERP

systems

The users should have an overall process to work

with, and be put in charge of sub-processes

The users should explain what their sub-process

is to other users working on the same overall

process but with adjacent sub-processes

The users should explain how their sub-process

utilizes the functionality of the system

The users should be engaged to discuss the

potential shortcomings and risks associated with

using the ERP system as process support

In 2008, a course module was designed and

implemented into an existing course on ERP systems

at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. The

lessons learned from this experience were reported

by Magnusson et al (2009) and involved both

technical and pedagogical aspects that needed

improvement. Overall, the result of the first attempt

at implementing the module into the curriculum was

regarded to be a success (Magnusson et al, 2009).

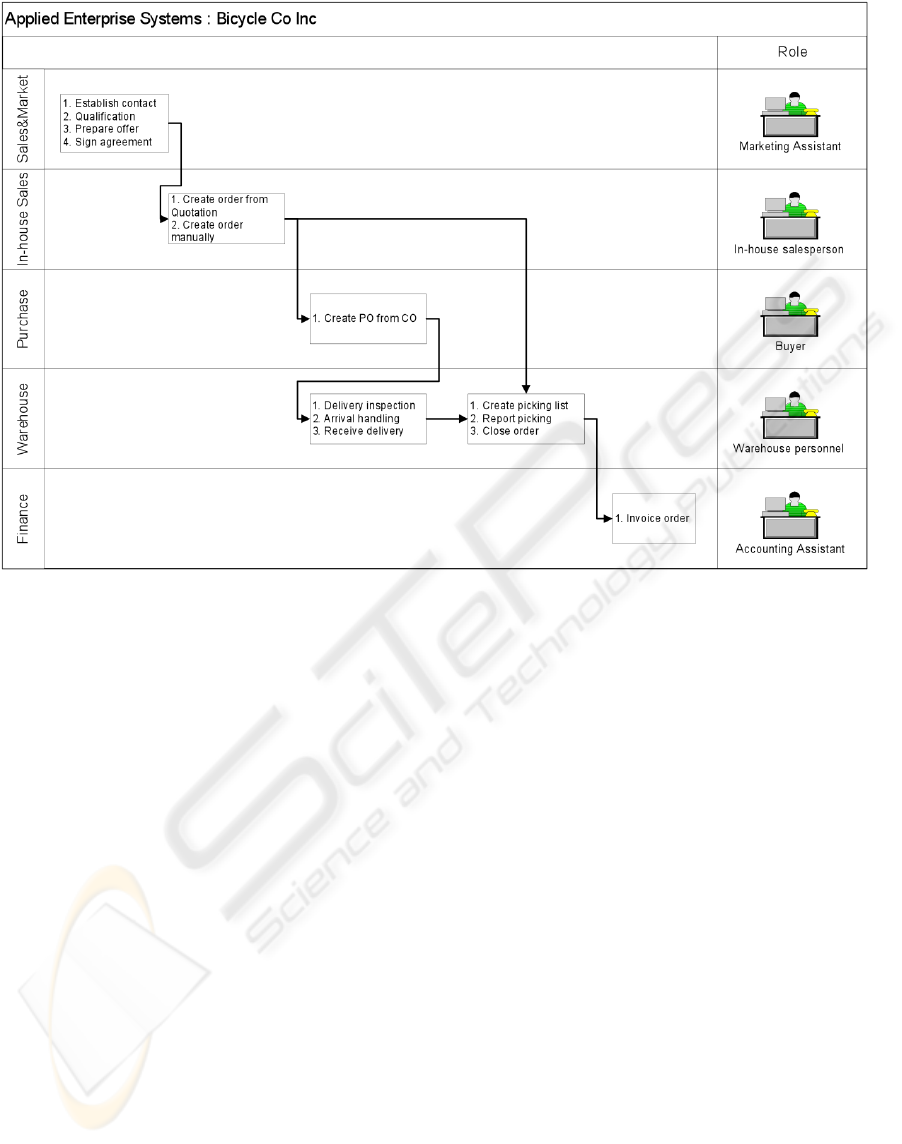

Following up on this success, a new attempt was

made in the fall of 2009. In this course (“Applied

Enterprise Systems”) the students were divided into

groups of 5-8 students and attributed roles following

the illustration below. They were then given a set of

exercises that involved them running both the entire

order-to-cash cycle by themselves, and, focusing

more in detail on their particular sub-process and the

functionality utilized for running this sub-process.

After an introduction to the system (this was the

first time the majority of the student body came in

contact with this particular system), the students

were given access to a Software-as-a-service

environment where the ERP system was

implemented.

The first exercise that the students completed

was a full order-to-cash cycle with the case of a

business opportunity appearing at a trade fair. They

then managed the customer, placed the order and

made sure that the order was delivered and an

invoice sent to the customer. This involved several

different user roles, whereby the first instance of the

system had the role of “CEO”, so that the students

had full access to the functionality.

The second exercise involved the students being

assigned particular roles (marketing assistant, et

cetera), where they had to go deeper into the

GET TOGETHER - A Case of ERP Implementation and its Transfer to Class

509

Figure 1: Processes, functions and roles.

particular functionality that their role had access to.

In tandem with this, they were given access to a

process-portal where the complete process that their

particular role was part of became visible for them.

Throughout the exercise, the students had full

access to the user instructions and system

documentation, and consultants were on site to

answer any questions that might arise.

After these two exercises, a debriefing was

scheduled. Working with lessons learned from the

previous attempt, the lecturers decided to conduct

the de-briefing without involving the students in

running the system on stage. Instead, one consultant

took charge of running the entire process, and a

lecturer was in charge of engaging the class in a

discussion.

This discussion was considered valuable through

the different questions that were raised. The students

were given an increased understanding of how both

a company and an ERP system works. With this de-

briefing conducted in the last week of class, it was

considered to be a usable method for going through

all the learning objectives of the course.

4 DISCUSSION

As shown in the case of Hestra, an early

involvement of the users into the ERP procurement

and implementation process was considered to be a

major success-factor for the company. Taking the

experience from Hestra as a starting point for the

design and implementation of a course-module on

ERP, the group of lecturers and consultants worked

with a set of assumptions. In Table 1, the lessons

learned related to each of these assumptions is

presented.

As a side note, the implications of taking a

starting point in a case of ERP procurement and

implementation that differs from the main stream

has several implications. On the one hand, it could

be seen as ethically questionable, since the students

are introduced to a style of procurement and

implementation that differs from much of what is

currently the de-facto standard. Since the students

are not adept with ERP procurement and

implementation, they are not in a position where

they can question the approach. At the same time

there is a lack of research showing that this approach

is advisable for organizations.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

510

Table 1: Assumptions and Lessons-learned.

Assumptions Lessons-learned

A process-oriented approach could

be used to shift the pedagogical

focus from technical exercises to an

increased understanding of the

business and the integrated nature of

ERP systems

The process-oriented approach aids the students in attaining a

higher level of knowledge on the links between the business and

ERP system. The experience is initially highly difficult for the

students, if they lack practical business understanding.

The users should have an overall

process to work with, and be put in

charge of sub-processes

The overall process needs to be communicated in a manner that

allows the students to navigate and explore the process

themselves. Process mapping tools such as Visio and work-flow

tools provide one means for achieving this. This process should

have the overall as well as all sub-processes fully specified, with

user instructions integrated so that the students have to start with

the process and then move towards the functionality.

The users should explain what their

sub-process is to other users

working on the same overall process

but with adjacent sub-processes

This proved to be asking too much of the students, and during the

second implementation of the course-module this was avoided.

Instead a consultant was set to in front of the group run through

the process and sub-processes and allow the students and faculty

to ask questions. This proved to be a better approach for reaching

the learning objectives of the course-module.

The users should explain how their

sub-process utilizes the

functionality of the system

See above.

The users should be engaged to

discuss the potential shortcomings

and risks associated with using the

ERP system as process support

This proved to be a great means for achieving the overall

learning objectives of the course on ERP systems. A number of

interesting and thought-provoking questions arose during the

debriefing that aided the students in acquiring a more thorough

understanding of the limitations and potential of ERP systems.

On the other hand, it could be considered a

means of showing the students that there are

multiple means of approaching the difficulties

associated with ERP procurement and

implementation. Provided that there is time for a

discussion in regards to the singularity of this

approach, related to an overall ERP discussion and

that the students are given the possibility of

reflecting about the process, this is not considered to

be a substantial draw-back of the approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the respondents and

management team of Hestra for allowing us to

access their organization for our research.

REFERENCES

Aladwani, A.M. (2001). “Change management strategies

for successful ERP implementation”. Business Process

Management Journal, 7(3): 266-75

Davenport, T.M. (1998). ”Putting the enterprise into the

enterprise system”. Harvard Business Review

David, J.S., Maccracken, H. & Reckers, P.M.J. (2003).

“Integrating technology and business process analysis

into introductory accounting courses”. Issues in

accounting education, 18(4):417-425

Ganley, D. (2008). Address give key factors for successful

ERP implementations. Gartner Group.

Hakim, A. & Hakim, H. (2010). “A practical model on

controlling the ERP implementation risks”.

Information Systems, 35(2):204-214

Hawking, P., Foster, S. & Bassett, P. (2002). ”An Applied

Approach to Teaching HR Concepts Using an ERP

System”. Proceedings of InSITE – “Where Parallels

Intersect”, InformingScience, pp. 699-704.

GET TOGETHER - A Case of ERP Implementation and its Transfer to Class

511

Hayen, R.A. & Andera, F.A. (2005). “Investigation of the

integration of SAP enterprise software in business

curricula”. Issues in Information Systems, VI(1):107-

113.

Hong, K.-K., & Kim, Y.-G. (2002). “The critical success

factors for ERP implementation”. Information &

Management, 40(1): 25-40

Kumar, V., Maheshwari, B. & Kumar, U. (2003). “An

investigation of critical management issues in ERP

implementation: empirical evidence from Canadian

organizations”. Technovation, 23(10): 793-807

Magnusson, J., ENquist, H., Oskarsson, B. & Gidlund, A.

(2009). “Process methodology in ERP-related

education: A case from Swedish higher

education”. BIS 2009 Conference post-proceedings.

Nelson, R. (2002). “AMCIS 2002 Workshops and Panels

V: Teaching ERP and Business Processes Using SAP

Software”. Communications of the AIS 9:392-402.

Rosemann, M, Scott, J. & Watson, E. (2001).

“Collaborative ERP Education: Experiences from a

First Pilot”. Proceedings of AMCIS 2001, pp. 2055-

2060.

Sammon, D. & Adam, F. (2010). “ Project Preparedness

and the emergence of implementation problems in

ERP projects”. Information & Management, 47(1):1-8

Upton, D.M. & Staats, B.R. (2008). Radically simple IT.

Harvard Business Review

Wixom, B. (2004). “Business Intelligence Software for the

Classroom: Microstrategy Resources on the Teradata

University Network”. Communications of the AIS. 14:

234-246.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

512