TOWARD A MODEL OF CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

An Action Research Study within a Mobile Telecommunications Company

Michael Anaman and Mark Lycett

Department of Information Systems and Computing, Brunel University,Uxbridge,UB8 3PH, U.K.

Keywords: Customer experience, Mobile telecommunications, Real-time marketing, Customer retention, Decision

support, Information systems integration.

Abstract: Retaining profitable and high-value customers is a major strategic objective for many companies. In mature

mobile markets where growth has slowed, the defection of customers from one network to another has

intensified and is strongly fuelled by poor customer experience. In this light, this research-in-progress paper

describes a strategic approach to the use of Information Technology as a means of improving customer

experience. Using action research in a mobile telecommunications operator, a model is developed that

evaluates disparate customer data, residing across many systems, and suggests appropriate contextual

actions where experience is poor. The model provides value in identifying issues, understanding them in the

context of the overall customer experience (over time) and dealing with them appropriately. The novelty of

the approach is the synthesis of data analysis with an enhanced understanding of customer experience which

is developed implicitly and in real-time.

1 INTRODUCTION

Organisations competing for the same customers and

broadly offering the same products and services

have differing levels of success in the market.

Published statistics indicate that 85% of business

leaders propose that differentiation by price, product

and services is no longer a sustainable business

strategy (Shaw and Ivens 2002). A significant

percentage of those leaders (71%) stated a belief that

customer experience is the new battleground in

achieving differentiation.

Customer experience comes from a customer’s

interaction with an organisation and its products and

services – it is not a passive concept. As a

consequence, this has led some to see experience as

a distinct economic offering (Pine and Gilmore

1998). In practice, however, the majority of

initiatives oriented at understanding customer

experience are reactive and based on gathering

explicit data related to experience (most commonly

gathered through customer surveys).One issue that

remains, however, is that of translating a strategy of

addressing customer experience to pro-active

operation that enhances the reactive approach of

asking customers about their experience. This paper

addresses that issue by developing a flexible and

maintainable model for analysing individual

customer experiences. The model is developed from

an analysis of data residing across a number of

technology-based information systems that, when

combined, allows for surrogate measures of

customer experience to be applied and appropriate

actions for improving customer experience to be

suggested.

The development of this model is presented in

the context of an in-progress action research study

with a major mobile telecommunications provider

(referred to as Telco hereafter). In developing the

model the paper is structured as follows. Section 2

presents an overview of the importance of customer

experience in relation to other concepts such as

loyalty and customer retention and describes the

important facets used in developing the model. It

also highlights the action research approach and

provides an overview of the Telco. Section 3

validates the customer experience concepts. Section

4 presents the model of customer experience, sheds

light on its application within Telco and discusses

the real-time marketing strategies. Section 5 notes

the current limitations of the work and describes the

next steps to be taken. Then the conclusion in

Section 6 follows.

385

Anaman M. and Lycett M. (2010).

TOWARD A MODEL OF CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE - An Action Research Study within a Mobile Telecommunications Company.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support Systems, pages

385-390

DOI: 10.5220/0002888003850390

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 KEY FACETS OF CUSTOMER

EXPERIENCE

Mobile penetration has reached a saturation point in

many markets, which has led providers to realize

that retaining existing customers is of increasing

importance. The typical focus points of retention

have been those of increasing both customer loyalty

and customer value (Kim et al., 2004; Reinartz and

Kumar 2002). The business case for this realization

is compelling, with evidence indicating that the net

present value in profit that results from a 5%

increase in customer retention varies between 25 and

95% (Reichheld 1996), the top 10% of customers are

often worth 5 to 10 times as much in potential life

time profits as the bottom 10% (Reichheld 1996),

and it can cost a business up to five times more to

recruit new customers than to retain current

customers (Hart et al. 1990).

Though much work has been done on

satisfaction and loyalty, more recent, work has

demonstrated the impact that improving the

customer experience has on customer loyalty (see

Johnston and Michel 2008, Crosby and Johnson

2007).

To date the information systems literature has

tended to focus on flow theory and studies of

human-computer interaction as a framework for

modelling enjoyment, user satisfaction, engagement

and other related states of involvement with

computer software (Novak et al, 2000; Pace, 2003;

Finneran & Zhang, 2003; Khalifa & Liu, 2007). This

paper, however, focuses on the basic satisfiers or

hygiene factors for mobile communication. The

paper contends that the mobile industry faces far

more elementary challenges in comparison to

ensuring customer experience flow in their

interaction with products and services.

Poor experience is generally conceptualised as an

‘expectation gap’ – the difference between what the

customer thinks they should be getting (built up by

marketing promises and prior experiences with the

existing company or other companies) and the

experience that they receive (as a result of

operational design for efficiency) (see Millard

2006).

Managing customer experience consequently

means “orchestrating all the customer experience

‘clues’ that are given off by products and services

that customers detect in the buying process” (Berry,

Carbone and Haeckel 2002, p.85). These clues are

easily discerned – in essence, a clue is anything that

can be perceived or sensed or recognised by its

absence. The composite of all clues comprise the

customer’s total experience and they can be

subdivided into categories as noted below (Carbone

and Haeckel 1994): Functional – Rational / objective

clues that relate to the operation of the good or

service; Emotional (Mechanics) – Clues emitted by

things; Emotional – (Humanics) – Clues emitted by

people.

Emotional clues are just as important to the

customer experience and work synergistically with

functional clues (Berry et al. 2002), a view

supported by Shaw (2005) who suggests that sensory

experience is vital when looking at the entire

customer experience. Very importantly, the

customer experience should be viewed as a process

of interaction and can be mapped out as a journey

(Reichheld 1996) – a ‘customer corridor’ that

captures the essence of a series of interactions.

Understandably, the preference for the development

of this sequence is for the interactions to be positive

and both the average interaction and the deviations

from the average (peaks) are important in shaping a

customer’s overall experience (see Verhoef et al.

2004 in relation to services). Other research notes

the importance of the last interaction over and above

prior interactions (Ariely and Carmon 2000; Hansen

and Danaher 1999).

From an industrial perspective, clues are

classified in instruments such as the J. D. Power

Survey (J. D. Power & Associates 2008), which is

an industrial standard in the UK. The categories

cover seven key factors and their relative weightings

(in brackets): Image (23%); Offerings & promotions

(14%); Call quality / coverage (18%); Cost (14%);

Handset (7%); Customer Service (14%); Billing

(10%).

2.1 Action Research and the

Organisational Setting

The practical work herein is action research based,

adopting a two pronged approach which are the

distinctive characteristics of action research (see

Avison et al. 1999, Baskerville and Wood-Harper

1996, Davison et al. 2004). Though various forms of

action research have been identified (Baskerville and

Wood-Harper 1998), the research here is canonical

in its approach, comprising the five phases of (1)

diagnosing; (2) action planning; (3) action taking;

(4) evaluating and (5) specifying learning (Davison

et al. 2004, Susman and Evered 1978).

The research organisation, Telco, is a mobile

telecommunications company with network

operations in several countries servicing millions of

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

386

customers. The research was conducted in the

context of the UK business.

2.2 Explicit vs. Implicit Assessment of

Customer Experience

When faced with measuring customer experience a

significant challenge is whether to explicitly ask

customers about their experiences or try to inferred

experiences implicitly. For the UK mobile industry,

explicit measurement is problematic for the

following reasons: a) the logistics and cost to

continually survey an appropriate proportion of the

customer base; b) dealing with the fact that explicit

methods rely on the recollection of events by

customers which are often overly positive (in a “rose

tinted” manner) or they can be remembered more

negatively than the reality at the time; c) the concern

that many consumers are suffering from survey

fatigue where continued requests from operators for

information can be counter productive; d) the wrong

customers respond – often it is customers that are

bored, lonely or compulsive that answer. Reichheld

(1996) agrees with the above problems and suggests

that as tools for predicting whether customers will

purchase more of the company’s products or

services (which he suggests is a good surrogate for

determining whether a company is providing a good

experience or not) explicit satisfaction surveys are

grossly imperfect.

These challenges directed the research and the

development of an implicit and more proactive

approach, where experience data stored or accessible

by the company can be harnessed with the creation

of systems solution to improving customer

experience.

2.3 Scoring the Customer Experience

Following a review of alternatives, Reichheld’s Net

Promoter Scoring system was adopted as a

measurement scale. This scale divides every

company’s customers into three categories:

Promoters, Passives, and Detractors. By asking how

likely is it that you would recommend an

organisation to a friend or colleague, customers

respond on a 0-to-10 point rating scale and are

categorized as follows: Promoters (score 9-10) are

loyal enthusiasts who will keep buying and refer

others, fuelling growth; Passives (score 7-8) are

satisfied but unenthusiastic customers who are

vulnerable to competitive offerings; Detractors

(score 0-6) are unhappy customers who can damage

your brand and impede growth through negative

word-of-mouth.

The Net Promoter Score (NPS) is calculated by

taking the percentage of customers who are

Promoters and subtract the percentage who are

Detractors. Following a review of options, this

scoring system was employed as it had credibility

within Telco and therefore provided no challenges to

adoption.

3 VALIDATION OF CUSTOMER

EXPERIENCE CONCEPTS

Customer experience concepts were derived via a

process of data triangulation. This process

synthesised data from the customer experience

literature, the JD Power Survey (both areas

previously discussed) and the thoughts from real

customers (described below), with the aim of further

validating the customer experience items and their

relative importance. The survey of real customers

involved a 5 minute semi-structured interview with

Telco customers as they were entering or leaving

Telco retail stores which were conducted

simultaneously across 4 different geographical

locations. A sample of 94 customers was surveyed

with Telco advising that the demographic split was

representative of their total customer base.

When asked how rated their experience with

Telco at the moment, using Reichheld’s 0 – 10 scale,

34% were classified as promoters, 34% were

passives and 32% were identified as detractors,

indicating there is an opportunity for Telco to make

improvements to their customer experiences. When

the customers were asked about the key reasons for

their rating, the results showed that customer

services has by far the biggest impact on the

experience rating, with nearly half the customers

sampled (47%) seeing this as the primary issue.

However upon analysis, promoters place an even

greater emphasis on customer services (56%),

whereas detractors suggest that both coverage and

customer services are key reasons for their rating

with (30% and 27% respectively).

When asked what Telco could do to improve the

experience, the top 3 answers (excluding null

answers) were: Improve customer service – (47%);

Improve costs – (19%); Improve Coverage (16%).

TOWARD A MODEL OF CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE - An Action Research Study within a Mobile Telecommunications

Company

387

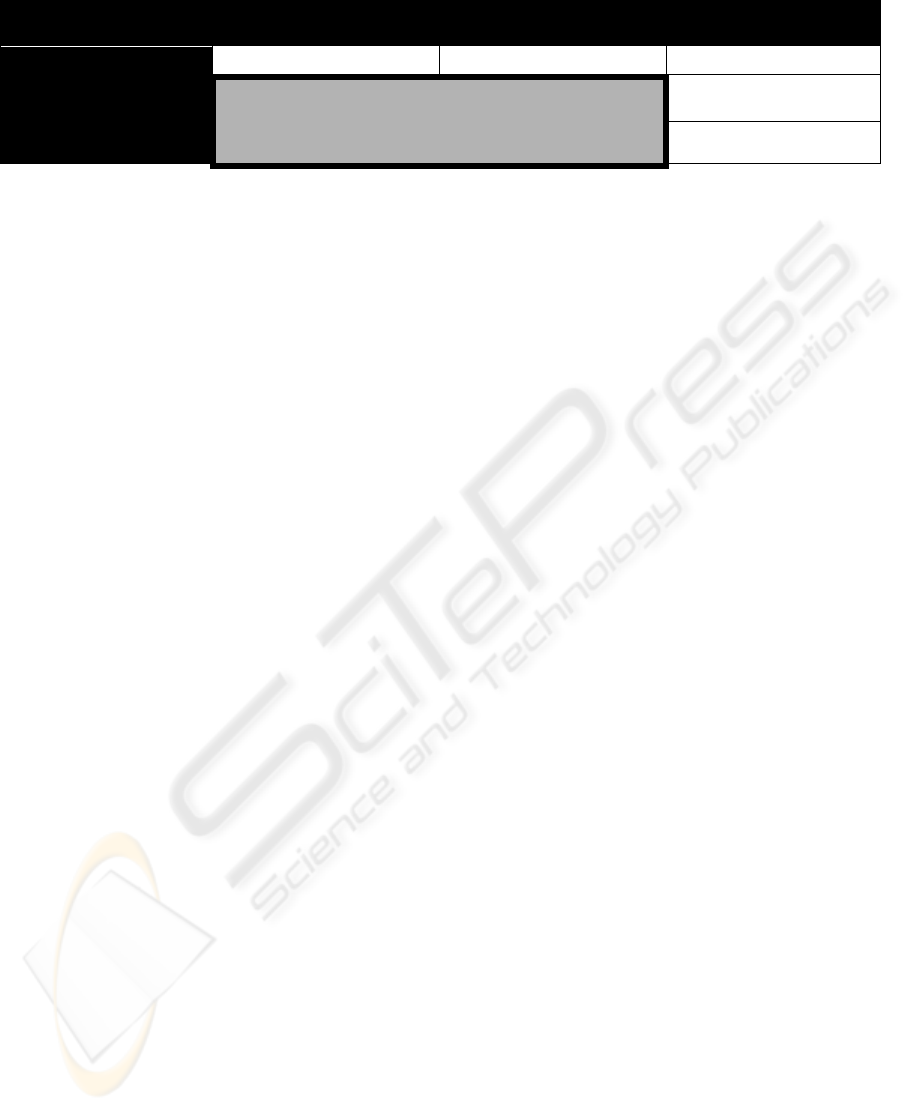

Table 1: Outline of Customer Experience Model.

Experience

Category

Weighting Experience Item Item Description Weighting

Cost 0.1818 Cost

competitiveness

Telco customers’ cost per minute voice/text bundle

versus the cost per minute bundle for the cheapest

competitor

0.66

Bundle efficiency Percentage of bundle allocation used per month 0.34

Handset 0.0909 Repairs Number of times handset has been in for repair in a

12 month period

0.75

Known issues Known issues with existing handset 0.25

Coverage 0.2338 Dropped calls Percentage of dropped calls, based on totals

number of calls made in that month

0.40

Call Set-up failures Percentage of call set up failures, based on number

of calls made

0.30

Home coverage Coverage rating at home post code 0.30

Customer Services 0.1818 Complaint

repetition

Percentage of customer complaints with the same

reason code in a 12 month period

0.60

Complaint volume Number of customer complaints in a 12 month

period

0.40

Offerings &

Promotions

0.1818 Decrease in voice

usage

Percentage decrease in voice usage vs. previous

month

0.45

Decrease in data

usage

Percentage decrease in data usage vs. previous

month

0.45

Decrease

promotion usage

Percentage decrease in usage of latest promotional

offer taken up

0.10

Billing 0.1299 Billing complaints Number of customer complaints regarding billing

in a 12 month period

1.00

4 CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

MODEL AND REAL TIME

MARKETING

4.1 Customer Experience Model

Development

In developing a systems model, the J.D. Power

categories were broken down into experience items,

with weighting validated by the exit interview

customer survey and based on the experience and

knowledge of the joint team. The items were

selected as those that would give a great implicit

experience indication for each category. Meyer and

Schwager (2007) in particular argue that companies

must deconstruct their overall experience into

component experiences and proposes that

organisations may choose to review past, present or

potential patterns of customer experience data, with

each pattern yielding different types of insight.

Table 1 provides a summary of the customer

experience model. Drawing the earlier parts of the

paper together, for each customer, the model allows

for computational profiles to be developed

(accounting for individual customer journeys). From

an abstract perspective profiles are enabled by

categorising and measuring experiences over time.

The customer experience items are the indicators

derived from data in the organisations source

systems (Customer Care; Billing; Sales; Network

performance; Competitor intelligence). Using data

warehousing technology this base data can be

cleansed and aggregated into the relevant time

period and provided for each individual customer. A

customer experience score can therefore be arrived

at by aggregating the score for each category. The

theoretical maximum would be 1.0, however, any

issues at the experience item level will reduce the

maximum value of that category and thus the overall

experience score.

4.2 Application of the Model in a Real

Time Marketing Setting

Real-time attempts to ensure goods and services are

not only customisable to the individual customer,

but also inherently capable of adapting themselves

over time (Oliver et al., 1998). Telco see real-time

marketing as an opportunity to turn interactions

triggered by either the customer or the organisation

into more profitable customer relationships. They

also believe that insight driven customer service can

optimise interactions and generate incremental

revenue and greater loyalty. Importantly, Telco also

believe that real-time marketing initiatives provide

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

388

Table 2: Loyalty Action Strategies.

Value

Experience

High (>£27) Medium (> £13, but <£27) Low (<£9)

High (Promoters)

Cross –sell Cross –sell Up-sell

Medium (Passives)

Implement loyalty action Implement loyalty action Up-sell

Low (Detractors)

Implement loyalty action Implement loyalty action Do nothing

an opportunity to further assess the customer

experience model and implement actions to address

poor customer experience. Table 2 provides a high

level strategic view of how different customer

interaction would proceed, based on a customer

experience score and knowledge of customer value.

From a customer experience and retention

perspective most interest lies in the scenarios where

high or medium value customers (depicted in the

table by monthly margin figures) are having a

medium or low experience. Actionable customer

feedback needs to relate specific problems to

specific groups of customers, in particular customers

with enough economic value to merit investing in

solutions to their concerns (Reichheld, 2006).

4.3 Customer Experience Improvement

(Service Recovery) and Loyalty

Actions

In their framework of the service recovery process,

Miller et al. (2000) categorise the critical elements

of the recovery process as either psychological or

tangible. Common tangible elements of a service

recovery system include completing the primary

service, re-performing the service, exchange the

product or refunding the cost (Lewis and McCann,

2004).

The importance of action is highlighted in the

case of service recovery. Service recovery where

possible attempts to solve problems at the service

encounter before customers complain or before they

leave the service encounter dissatisfied (Michel

2001). The pre-emptive nature of the model allows

Telco to intervene to improve the experience, before

the situation becomes un-recoverable.

Examples of loyalty actions formulated by the

team for high value customers include:

• “More economic tariffs” – forgoing short term

margin for more medium term profits due to

less churn.

• “Immediate replacement of problem handsets”

– reducing the aggravation period and ensure

the customer is able to use billable services

sooner.

5 NEXT STEPS AND

IMPLICATIONS

The customer experience model, as developed here,

is currently being tested and validated for is efficacy

and impact on identifying customer experience

issues and improving business performance. Testing

and validation is being conducted on data for 20,000

customers, covering the experience items articulated

in the model. The sample intentionally includes

10,000 customers who defected at the end of their

contract period and 10,000 customers who upgraded

their contracts or continued on their existing

contracts. Statistical analysis will be therefore be

used to examine correlation between experience

items and between experience items and defection.

That analysis will also be used to calibrate the

model, testing and refining item weightings and the

thresholds for triggering loyalty actions. Following

implementation, further research is currently being

undertaken to:

• Assess the impact of loyalty actions in

resolving issues and developing a closer

relationship with the customer.

• Examine the wider organisational

implications, reviewing the impact on process

improvement and employee satisfaction. Even

at this stage, it is clear that corporate measures

and incentives will need to be reviewed to

support the new customer experience

approach.

Understandably, there are limitations in relation

to the research and the customer experience model

in general. First, the research is based on the

activities and information of one mobile operator,

which places limits on generalisation of the

outcomes. Second, there are limitations in relation to

both what can be measured and the metrics

employed, those in the model to date flow from the

TOWARD A MODEL OF CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE - An Action Research Study within a Mobile Telecommunications

Company

389

data available in existing systems and decisions

taken in concert with Telco. Third, it is

acknowledged that the indicators employed are

functional in their nature and do not explicitly

address emotional clues in the main. This point was

acknowledged at the outset and the model is

intended (a) to provide an implicit ‘foil’ for explicit

initiatives such as customer surveys and (b) the

delivery of loyalty actions is via human-to-human

interaction (in a contrite and empathetic manner).

6 CONCLUSION

Retaining profitable and high-value customers is a

major strategic objective for many companies – a

statement particularly true for firms in mature

mobile markets where growth has slowed and the

defection of customers from one network to another

has intensified. From a business perspective the case

for addressing loyalty has been shown as compelling

and this paper has argued that understanding and

improving customer experience is a cornerstone in

improving loyalty. Though customer experience has

been shown to be difficult to tie-down, from a

management perspective, it has been argued that it is

important to understand and model on a longitudinal

basis to understand the ‘journey’ that a customer is

on and how particular interactions impact upon the

overall experience.

In seeking to make the management of

experience operational, a model has been developed

that infers (primarily) functional clues that can be

used as surrogates for customer experience, drawing

on customer data (both static and from interaction)

to highlight issues and suggest appropriate actions to

improve the experience. The model itself comprises

of a number of experience items developed as a

synthesis of empirical research, prior literature and

an industry-standard model. Experience items are

monitored and assessed in relation to agreed

thresholds. The value of this model is in identifying

issues, understanding them in the context of the

overall customer experience (over time) and dealing

with them appropriately. The novelty of the

approach is the synthesis of data analysis with an

enhanced understanding of customer experience

which is developed implicitly and in real-time. The

work is presented as research-in-progress and is

currently being tested and validated for is efficacy

and impact on Telco data for 20,000 customers.

REFERENCES

Avison, D.E., Lau, F., Myers, M.D. and Nielsen, P.A.

1999. Action Research, Communications of the ACM

42 (1), January, pp. 94-97.

Baskerville, R., and Wood-Harper, A.T. 1998. Diversity in

Information Systems Action Research Methods,

European Journal of Information Systems 7 (2), pp.

90-107.

Berry, L; Carbone, L., and Haeckel, S. 2002. Managing

the total customer experience, MIT Sloan Management

Review 43 (3), Spring.

Carbone, L.P. and Haeckel, S.H. 1994. Engineering

Customer Experiences, Marketing Management 3 (3),

Winter, p8-19.

Crosby, L.A. and Johnson, S.L. 2007. Experience

required. Marketing Management, July/August.

Davison, R.M., Martinsons, M.G. and Kock, N. 2004.

Principles of canonical action research, Information

Systems Journal, 14 (1), pp. 65-85.

J.D. Power & Associates. 2008. UK Mobile Telephone

Customer Satisfaction Study.

www.jdpower.com/corporate/news/releases.

Johnston, R. and Michel, S. 2008. Three outcomes of

service recovery: Customer recovery; process recovery

and employee recovery, International Journal of

Operations and Production Management 28 (1), pp.

79-99.

Meyer, C; and Schwager, A. 2007. Understanding the

customer experience, Harvard Business Review 85 (2),

February, pp. 116 – 126.

Pace, S. 2003. A grounded theory of the flow experiences

of web users, International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 60, pp. 327 – 363.

Pine, B.J. and Gilmore, J.H. 1998. Welcome to the

experience economy, Harvard Business Review. July-

August, pp 97 -105.

Prahalad, C.K., and Ramaswamy, V. 2004. The future of

competition: Co-creating unique value with customers.

Harvard Business School Press.

Reichheld, F.F. 1996 The loyalty effect. Harvard Business

School Press.

Reichheld, F.F. 2006. The Ultimate Question: Driving

good profits and true growth. Harvard Business

School Press.

Reinartz, W., Kumar, V. 2002. This mismanagement of

customer loyalty. Harvard Business Review, 80 (7),

pp. 84-96.

Shaw, C. and Ivens, J. 2002 Building Great Customer

Experiences, Palgrave Macmillan.

Susman, G.I. and Evered, R.D. 1978. An Assessment of

the scientific merits of action research, Administrative

Science Quarterly 23 (4), pp. 582-603.

Verhoef, P.C., Antonides, G. and de Hoog, A.N. 2004

Service encounters as a sequence of events: The

importance of peak experiences, Journal of Service

Research 7 (1), pp. 53 -64.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

390