EVALUATION OF AN ANTHROPOMORPHIC USER

INTERFACE IN A TELEPHONE BIDDING CONTEXT AND

AFFORDANCES

Pietro Murano

School of Computing Science and Engineering, University of Salford, Gt. Manchester, M5 4WT, U.K.

Patrik O’Brian Holt

Interactive Systems Research Group, School of Computing, The Robert Gordon University

St. Andrew Street, Aberdeen, AB25 1HG, Scotland

Keywords: Anthropomorphism, User Interface Feedback, Evaluation, Affordances.

Abstract: Various researchers around the world have been investigating the use of anthropomorphism in some form at

the user interface. Some key issues involve determining whether such a medium is effective and liked by

users. Discovering conclusive evidence in relation to this medium would help user interface designers

produce better user interfaces. Currently conclusive evidence is lacking. However the authors of this paper

have been investigating these issues for some time and this paper presents the results of an experiment

which tested anthropomorphic voices against neutral voices. This was in the context of telephone bidding.

The results indicated the impersonal human voice condition to foster higher bids, while the user satisfaction

was inconclusive across all four conditions tested. The results have also been examined in terms of the

Theory of Affordances with the aim of finding an explanation for the observed results. The results indicate

that issues of affordances played a part in the results observed.

1 INTRODUCTION

The idea of using anthropomorphic feedback at the

user interface has been around for some time and has

attracted attention from researchers around the

world. One of the concerns of such types of user

interfaces or feedback that is anthropomorphic is

whether it is effective and liked by users. While an

answer to this issue may appear to be intuitive, the

evidence so far in the research community is that it

is still an open issue requiring to be solved. Solving

such as issue would help to increase the usability of

user interfaces and the applications behind them.

Products can fail if their usability is not at its best.

Despite efforts over the years at resolving these

usability issues, results from various studies indicate

a lack of a clear pattern of results leading to

appropriate conclusions.

Therefore the authors of this paper are

investigating the effectiveness and user satisfaction

of anthropomorphic type user interfaces and

feedback in various contexts. To achieve this, the

authors are using rigorous experimental techniques

to gather data which is then statistically analysed.

Appropriate links are also being made with existing

theories, such as the theory of Affordances.

Anthropomorphism at the user interface usually

involves some part of the user interface, taking on

some human quality (De Angeli, Johnson, and

Coventry, 2001). Some examples include a synthetic

character acting as an assistant or a video clip of a

human (Bengtsson, Burgoon, Cederberg, Bonito and

Lundeberg, 1999).

In a study by Hongpaisanwiwat and Lewis

(2003), in the context of teaching computer graphics,

the effects of using an animated character were

investigated. They designed a three condition

experiment, consisting of an animated character, a

‘pointing finger’ and no character. Synthetic or

human voices were used in all three conditions.

Their aims were to measure understanding and

concentration in the learning of the participants

whilst using a set of learning materials about

38

Murano P. and O’Brian Holt P. (2010).

EVALUATION OF AN ANTHROPOMORPHIC USER INTERFACE IN A TELEPHONE BIDDING CONTEXT AND AFFORDANCES.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Human-Computer Interaction, pages 38-44

DOI: 10.5220/0002894400380044

Copyright

c

SciTePress

computer graphics. The overall results showed no

significant difference in understanding with respect

to the participants using the animated character.

There was an interaction effect showing the

animated character with synthetic voice to be better

for remembering aspects of learning materials,

compared to the character with human voice

condition. Further, interaction effects were observed

showing that the amount of emphasised items

remembered by participants using the ‘pointing

finger’ and no character conditions with a human

voice was greater than participants using the

synthetic voice. Also, participants remembered more

in the animated character with synthetic voice

condition compared with the animated character

with human voice condition. There were no

significant differences concerning participants’

subjective opinions of the learning materials. Overall

this experiment did not provide any conclusive

evidence favouring the use of anthropomorphism.

The general results found by these authors does

not match with certain other research, e.g. Moreno,

Mayer and Lester (2000) in the context of tutoring

about plant design tended to find evidence that

anthropomorphic information was better when one

had to use learned knowledge to solve new similar

problems. Participants were also more positive

towards the anthropomorphic type information.

Further, in a study by David et al (2007), the

authors conducted a three condition experiment in

the context of a quiz about ancient history. They

were investigating different anthropomorphic cues in

terms of character gender and attitude and user

perceptions about the character in relation to quiz

success (or not). The overall results of their

experiment suggested that anthropomorphic cues led

to users believing the character to be less friendly,

intelligent and fair. This finding was linked with the

male character and not with the female character.

Lastly, in a study by Prendinger et al (2007)

which involved an investigation into using eye

tracking for data collection, the authors specifically

tested an animated character with gestures and

voice, voice only and text. The context they used

involved showing users around an apartment on a

computer monitor. Their main findings were that the

character condition seemed to be better for directing

‘attentional focus’ to various objects on the screen.

However the voice only condition fostered more

attention on the part of the users towards ‘reference

objects’ on the screen. They also observed that the

text only condition induced participants to look at

the text more than the character, in terms of gaze

points. Finally, subjective aspects were inconclusive.

Despite this study having some experimental flaws,

such as having very small sample sizes, it does

indicate that using an anthropomorphic entity is not

necessarily better than other modes.

In the authors’ own work (Murano et al, 2009),

an experiment in the context of downloading and

installing an email client, an anthropomorphic

character condition was tested against a non-

anthropomorphic textual condition. The conditions

were designed to assist novice users in the act of

downloading and installing an email client. The

main results indicated the anthropomorphic

condition to be more effective (based on various

errors and user behaviour) and preferred by

participants.

However, we have also seen that this pattern of

results does not hold for all our work. In another

study by Murano et al (2008) in the context of PC

building instructions, an anthropomorphic character

condition was tested against a non-anthropomorphic

text condition. For this experiment the main results

for effectiveness (based on errors) were

inconclusive. However the results for subjective

satisfaction were slightly more tending towards a

preference for the anthropomorphic condition. (The

reader is also referred to further work carried out by

the principal author of this paper indicating a lack of

an overall pattern in results for effectiveness and

user satisfaction (Murano and Holt, 2009, Murano et

al, 2007 and Murano, 2005).

A brief review of some key work in this area

confirms that overall results regarding effectiveness

and user satisfaction are currently inconclusive.

There could be various reasons for these results.

Some reasons could concern specific context or

aspects of experimental design. However another

explanation could concern aspects of certain key

affordances either being violated or properly

facilitated.

The original Theory of Affordances (Gibson,

1979) has been extended by Hartson (2003) to cover

user interface aspects. Hartson identifies cognitive,

physical, functional and sensory affordances. He

argues that when a user is doing some computer

related task, they are using cognitive, physical and

sensory actions. Cognitive affordances involve ‘a

design feature that helps, supports, facilitates, or

enables thinking and/or knowing about something’

(Hartson, 2003). One example of this aspect

concerns giving feedback to a user that is clear and

precise. If one labels a button, the label should

convey to the user what will happen if the button is

clicked. Physical affordances are ‘a design feature

that helps, aids, supports, facilitates, or enables

EVALUATION OF AN ANTHROPOMORPHIC USER INTERFACE IN A TELEPHONE BIDDING CONTEXT AND

AFFORDANCES

39

physically doing something’ (Hartson, 2003).

According to Hartson a button that can be clicked by

a user is a physical object acted on by a human and

its size should be large enough to elicit easy

clicking. This would therefore be a physical

affordance characteristic. Functional affordances

concern having some purpose in relation to a

physical affordance. One example is that clicking on

a button should have some purpose with a goal in

mind. The converse is that indiscriminately clicking

somewhere on the screen is not purposeful and has

no goal in mind. Lastly, sensory affordances concern

‘a design feature that helps, aids, supports, facilitates

or enables the user in sensing (e.g. seeing, feeling,

hearing) something’ (Hartson, 2003). Sensory

affordances are linked to the earlier cognitive and

physical affordances as they complement one

another. This means that the users need to be able to

‘sense’ the cognitive and physical affordances so

that these affordances can help the user.

Therefore, in section 2 the experiment and results

are discussed. In section 3 the results of the

experiment are discussed in light of the Theory of

Affordances as identified by Hartson (2003). Then

in section 4 some overall conclusions and proposals

for ways forward for the research are presented.

2 VOICES AND BIDDING

EXPERIMENT

2.1 Aims

This particular experiment aimed to specifically

investigate personal voices (e.g. a personal voice

could say: ‘I am your helper’) and neutral voices

(e.g. a voice could say: ‘This is your help’) and

human and text-to-speech (TTS) voices. This was in

the context of trying to determine which voice type

may have been more effective and preferred by

users. Nass and Brave (2005) have also used voices

in some of their experiments where their overall

aims were to discover how users react in a social

manner towards a computer. They specifically were

not investigating anthropomorphism.

2.2 Users

32 participants were recruited for this

experiment.

Although gender was not the main issue of this

research, the participants were students of

computer science. There were 25 male partici-

cipants and seven female participants.

Participants were in the 18-35 age range.

All participants had experience with online

bidding.

The participants were all recruited through the

principal author’s own classes at the university.

Specific details about the participants were then

elicited by means of a pre-experiment questionnaire

which principally asked specific questions about

bidding experience, e.g.

Have you ever used online auctions? Yes/No

(If your answer is NO, please go to Q. 7,

otherwise please answer parts (i) to (iii) before going

to Q. 7)

(i) State the name of the online auction you

used. ______________________

(ii) Did you purchase an item? Yes/No

(iii) Did you enjoy using the online auction?

Yes/No

2.3 Experimental Design

A between users design was used for this

experiment. This design method is good for

controlling issues of practice and order effects.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four

conditions. Randomness was achieved by alternately

assigning a participant to a condition until all

participants had been assigned to one of the four

conditions. The four conditions were impersonal

human voice, personal human voice, impersonal

Text-to-Speech (TTS) and personal TTS. The only

difference between the personal and impersonal

aspects, were that the personal utterances used

human-like language, e.g. ‘I…’ etc. and the

impersonal voices used neutral language. The human

voice was a clear English accented male voice of a

colleague. The TTS voice was a generic electronic

voice.

2.4 Variables

The independent variables were (1) the types of

feedback, (Voice Type, consisting of TTS personal

voice, TTS impersonal voice, Personal human voice

and Impersonal human voice) and (2) Type of Task

(Bidding on five different household items). This is

a 2x2 Factorial Design, where the values from the

bids made were averaged and included in the

analyses (i.e. not the tasks themselves).

The dependent variables were the participants’

performance in carrying out the tasks and their

subjective opinions.

The dependent measures were that the perfor-

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

40

mance was measured by examining the average bid

amount. From an auction point of view, the higher

the bid made, the better the business outcome. From

a user’s/buyer’s perspective the lowest amount is the

best outcome. The average bid was recorded by

means of an observation protocol. This was a small

grid which allowed the author to write down the bid

for each item bid. The average was then calculated

when the participant had left the experiment

location. The subjective opinions were measured by

means of a post-experiment questionnaire. The post-

experiment questionnaire had six main sections.

These were sections covering the usefulness of the

system, the trustworthiness of the system, the

formality of the system, the likeness to a person, the

participants’ feelings during the interaction and the

enjoyment of the system.

2.5 Apparatus and Materials

A laptop running Windows XP with 256 Mb

RAM.

The laptop’s own TFT display was used – 14”.

A headphone set with inbuilt microphone.

CSLU Toolkit (2009).

2.6 Procedure and Tasks

The recruitment questionnaire was handed out and

the completed forms were scrutinised for suitability.

The main aspect that was required for this

experiment was to have participants with an

awareness of online auctions. Also it was required

by implication to have participants with computing

knowledge so that the results would not be biased

with issues concerning lack of knowledge in using

computer systems, which could indirectly affect

bidding behaviour. This was assumed though as all

the participants were computer science students.

The suitable participants were then contacted by

email, where an appointment during the day was

arranged.

Upon arrival the participants were welcomed and

comfortably seated at the computer. They were

initially briefed with the following points:

All the data would be kept confidential, they

could leave at any time they wanted and should

they not want their data to be used after the

experiment had taken place, this was their

prerogative.

A scenario informing them that they had

graduated and were about to leave university and

had decided to obtain some household items by

means of a telephone auction.

Some general information was given regarding

how to use the microphone attached to the

computer.

Then the participants were asked to read the

content of a one page web site, which contained

more detailed information than the initial briefing

points.

When the reading was completed, the actual

auction was started. A virtual telephone keypad

appeared on the screen and the participants pressed

the speed dial button. An audible ring tone could be

heard and after a short while, the telephone was

answered by one of the voice conditions being

tested. The ‘voice’ gave an initial introduction

detailing that there were five items for sale. Then the

participant was informed that they would hear a

description for each item and that they would need

to bid at the end of each item’s description.

The next stage involved the ‘voice’ giving some

details of the item. The description gave a guide

price and a brief physical description of the item.

When the description was completed, a short beep

was heard which was the cue for the participant to

make their single bid via the microphone (the

participant had been initially briefed about this). The

amount bid was then discreetly written down by the

experimenter. When the single bid was made, the

system automatically proceeded to issue the

description for the second item in a similar manner.

This was done for five items in total. The actual

items were a futon, refrigerator, microwave oven,

television and a telephone answering machine.

When the five bids had been placed, the

participants were asked to complete a post-

experiment questionnaire regarding their subjective

opinions and feelings about their interaction

experience. When this was completed, they were

thanked for their time, asked to not tell anyone what

they had done and reminded that they were now

entered in a prize draw for their participation. This

procedure was followed in the same manner for all

the participants.

2.7 Results

The data were analysed using a multifactorial

analysis of variance and when significance was

found, the particular issues were then subjected to

post-hoc testing using in all cases either t-tests or

Tukey HSD tests (NB: DF = Degrees of Freedom,

SS = Sum of Squares, MSq = Mean Square). Firstly

EVALUATION OF AN ANTHROPOMORPHIC USER INTERFACE IN A TELEPHONE BIDDING CONTEXT AND

AFFORDANCES

41

the means and standard deviations are presented for

the results in Tables 1 to 3 below:

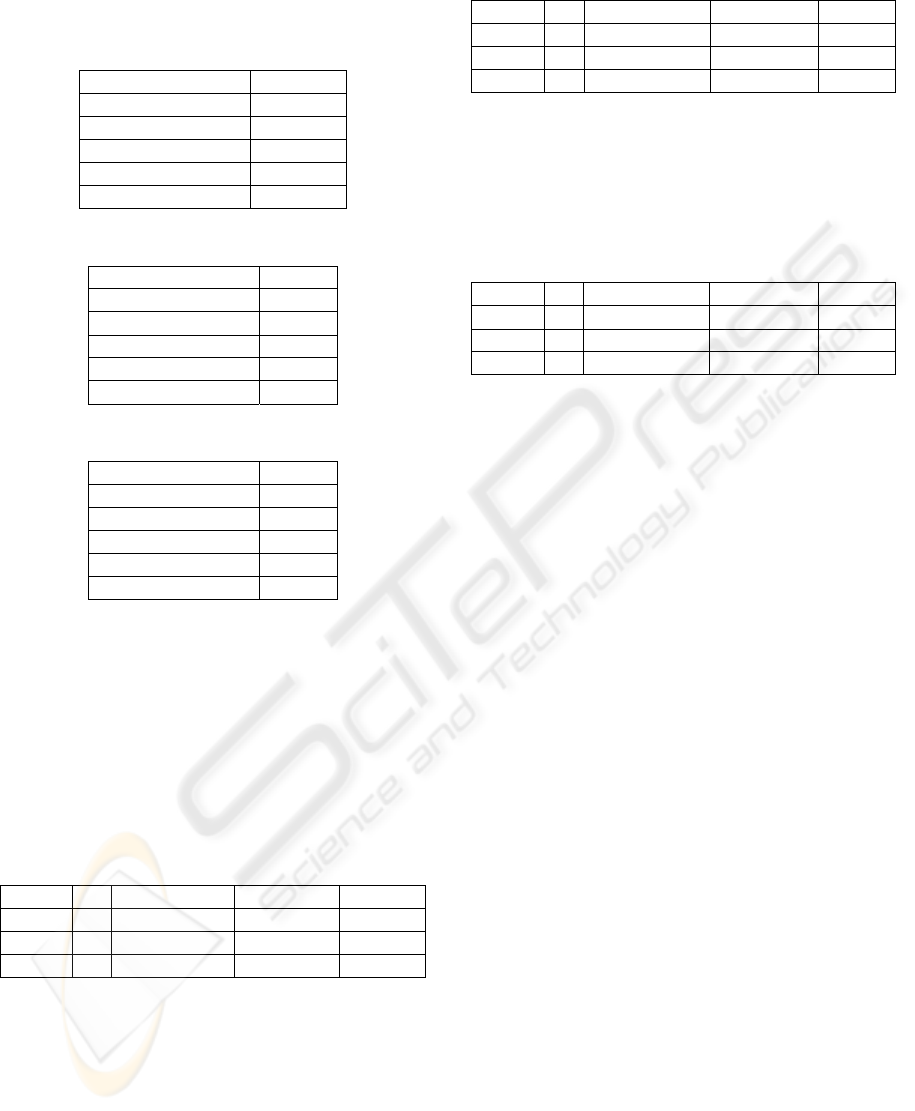

Table 1: Means and SD, Average Bid.

Mean 115

Std Dev 32.74

Std Err Mean 5.79

upper 95% Mean 126.80

lower 95% Mean 103.20

N 32

Table 2: Means and SD, Fair.

Mean 6.41

Std Dev 1.78

Std Err Mean 0.31

upper 95% Mean 7.05

lower 95% Mean 5.77

N 32

Table 3: Means and SD, Likeness to Person.

Mean 5.69

Std Dev 2.58

Std Err Mean 0.46

upper 95% Mean 6.62

lower 95% Mean 4.76

N 32

For the variables ‘average bid’ and ‘condition’

there is a significant (p < 0.05) difference. The

participants in the impersonal voice condition

significantly placed higher average bids than the

participants in the personal voice conditions. Also

participants in the personal TTS condition placed

significantly higher average bids than the personal

voice condition. The F-ratio is 4.21*. This is shown

in Table 4 below:

Table 4: MANOVA, Average Bid/Condition.

Source DF Sum of Squares Mean Square F Ratio

Model 3 13866.75 4622.25 4.21

Error 28 30730.75 1097.53 Prob > F

C. Total 31 44597.50 0.01

For the variables ‘likeness to person’ and

‘condition’ there is a significant (p < 0.05)

difference. The personal human voice was perceived

as significantly more like a person than the voices in

the other conditions. The F-ratio is 3.43*. This is

shown in Table 5 below:

Table 5: MANOVA, Likeness to Person/Condition.

Source DF Sum of Squares Mean Square F Ratio

Model 3 55.63 18.54 3.43

Error 28 151.25 5.40 Prob > F

C. Total 31 206.88 0.03

For the variables ‘fair’ and ‘condition’ there is a

significant (p < 0.05) difference. The impersonal

TTS voice was significantly perceived as being more

fair (or unbiased) than the other voice types. The F-

ratio is 3.77*. This is shown in Table 6 below:

Table 6: MANOVA, Fair/Condition.

Source DF Sum of Squares Mean Square F Ratio

Model 3 28.09 9.36 3.77

Error 28 69.63 2.49 Prob > F

C. Total 31 97.72 0.02

Lastly the data collected concerning subjective

opinions did not show any significant effects.

2.8 Discussion of Results

Participants perceived the personal human voice

condition to be more like a person than the other

conditions. This result had been expected as it was

one of the manipulations of the experiment.

Also, the results indicate with significance that

the highest bids were placed by participants in the

impersonal voice condition and participants in the

personal TTS condition placed significantly higher

average bids than the personal voice condition. The

reason for this result is unclear. However while the

recruitment procedure aimed to ascertain awareness

of bidding on the part of the participants, the

procedure did not ascertain perceptions of household

items and prior learned bidding strategies. These two

aspects could have biased the results if a number of

participants in the impersonal voice condition

happened to have certain perceptions about bidding

and household items. This could have more easily

happened given the fact that the sample size was

smaller than desired. This aspect is worthy of further

study in conjunction with a larger sample size.

Lastly there was a significant result for the

fairness issue, where the impersonal TTS voice

condition was perceived as being fairer than the

other voice types. However this voice type incurred

the second lowest average bids. One reason for this

outcome could be that the impersonal voice was

perceived as being more neutral and perhaps more

fair, however this aspect is also worthy of further

study.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

42

3 THE EXPERIMENT AND

AFFORDANCES

The experiment tested four different voice types

with an identical user interface. The results for user

satisfaction were inconclusive. However, as stated

above, the impersonal voice condition incurred

significantly higher bids than the other conditions.

This can be viewed as a form of effectiveness from

the perspective of an auction owner who may be

interested in achieving overall higher bids.

Due to the nature of the conditions involved and

the fact that the user interface was identical under

each of the four conditions, the authors conclude that

the affordances should have been the same

irrespective of the four different conditions. The

cognitive affordances would have involved the

virtual telephone keypad on the screen and the

voices issuing the items’ descriptions. These would

have facilitated the simulation of an on-screen or

online telephone call and the receiving of

descriptions enabling a bid to be placed.

The sensory affordances would have particularly

aided the feature of listening or hearing items’

descriptions. As stated these were so similar to one

another that these affordances should not have been

affected differently depending on the condition

tested.

Regarding the physical affordances, the on-

screen telephone keypad would have facilitated the

action of making a call. This was a large and clear

enough keypad to allow easy clicking. Even if this

was not the main aspect of the interaction, it would

have contributed to a positive effect on the

participants.

Lastly the functional affordances would also

have been equivalent, as the on-screen keypad was

the same for all participants and worked in the same

manner. Further the participants placed their bid via

the head mounted microphone, which also worked in

the same manner for all participants under all the

conditions being examined.

To that end the authors conclude that for this

experiment the four types of affordance would have

been equivalent under the four different conditions.

The only unclear aspect is that it is unknown why

one condition significantly incurred higher bids than

the other conditions. However the authors suggest

that if thought about, the action of deciding how

much to bid is not an issue to do with affordances.

Looking at the experimental tasks, there were

essentially four stages. Stage one involved using the

virtual keypad. It is suggested above that this would

have involved some affordances issues, but should

have been equivalent under each condition. Stage

two involved listening to a series of descriptions and

would have involved some affordances issues, but

should have been equivalent under each condition as

all that varied was the voice type and not the content

or ordering of the content of the descriptions. Stage

three involved the ‘mental’ or ‘internal’ process of

deciding how much to bid. This had nothing to do

with affordances as making the ‘internal’ decision

would probably be more affected by past

experiences and perceptions of the items (despite

trying to obtain balanced users). Finally stage four

involved uttering the bid into the microphone. As

discussed above the affordances for this stage should

have been identical under each condition as well.

Therefore the authors are suggesting that the user

interface aspects (i.e. virtual keypad, descriptions

and microphone) involving some manipulation on

the part of the user were equivalent to one another

and therefore so were the affordances. However the

actual ‘internal’ human process of making a decision

regarding how much to bid could have varied,

despite best efforts at obtaining balanced

participants. On the other hand the balance was

achieved in terms of awareness of bidding, but no

attempt was made to obtain perceptions about

household items or perceptions about attitudes to

bidding, e.g. ‘always bid as low as possible’ or

‘always bid what you think the item is worth’ etc.

Such attitudes could affect overall average bids.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND

FURTHER WORK

It is clear that there is still more work to be done in

relation to discovering if anthropomorphic user

interfaces are really usable and liked by users. We

are suggesting that effectiveness and user

satisfaction of anthropomorphic interfaces is linked

to whether the various strands of affordances are

being positively observed or ignored in interface

design. However the issue of the affordances

requires further study and experimentation. One

approach to further study could be to design and

develop prototypes in some domain and context.

This could be done by trying to develop one

prototype that specifically violates the four strands

of affordances and compare this with an equivalent

prototype that facilitates the four strands of

affordances. These could make use of

anthropomorphic feedback to maintain the theme of

the research. Furthermore, based on the experiences

EVALUATION OF AN ANTHROPOMORPHIC USER INTERFACE IN A TELEPHONE BIDDING CONTEXT AND

AFFORDANCES

43

of this research, the work would ideally require

several slightly different experiments investigating

the facilitation of affordances. The reason for this is

that conducting only one experiment and obtaining

only one set of results could give an incorrect overall

picture of the matter.

Future work should also address the main

shortcoming of this experiment. The sample size

used was rather small in nature and future

experiments should ideally have more participants.

Also future work should continue to ensure realistic

scenarios, such as the one adopted in this

experiment. Realistic scenarios would help the

research to be more applicable in the real world and

more readily accepted by actual user interface

designers.

REFERENCES

Bengtsson, B, Burgoon, J. K, Cederberg, C, Bonito, J, and

Lundeberg, M. (1999) The Impact of

Anthropomorphic Interfaces on Influence,

Understanding and Credibility. Proceedings of the

32nd Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences, IEEE.

CSLU Toolkit (2009) http://cslu.cse.ogi.edu/toolkit/

Accessed 2009.

David, P., Lu, T., Kline, S. and Cai, L., 2007. Social

Effects of an Anthropomorphic Help Agent: Humans

Versus Computers, CyberPsychology and Behaviour,

10, 3. Mary Ann Liebert Inc.

De Angeli, A, Johnson, G. I. and Coventry, L. (2001) The

Unfriendly User: Exploring Social Reactions to

Chatterbots, Proceedings of the International

Conference on Affective Human Factors Design,

Asean Academic Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1979) The Ecological Approach to Visual

Perception, Houghton Mifflin Co.

Hartson, H. R. (2003) Cognitive, Physical, Sensory and

Functional Affordances in Interaction Design,

Behaviour and Information Technology, Sept-Oct

2003, 22 (5), p.315-338.

Hongpaisanwiwat, C. and Lewis, M. (2003) The Effect of

Animated Character in Multimedia Presentation:

Attention and Comprehension, Proceedings of the

2003 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man

and Cybernetics.

Moreno, R., Mayer, R. E. and Lester, J. C. (2000) Life-

Like Pedagogical Agents in Constructivist Multimedia

Environments: Cognitive Consequences of their

Interaction. ED-MEDIA 2000 Proceedings, p. 741-

746. AACE Press.

Murano, Pietro (2005) Why Anthropomorphic User

Interface Feedback Can be Effective and Preferred by

Users, 7th International Conference on Enterprise

Information Systems, Miami, USA, 25-28 May 2005.

(c) - INSTICC

Murano, Pietro, Holt, P. O. (2009) Anthropomorphic

Feedback In User Interfaces: The Effect of Personality

Traits, Context and Grice's Maxims on Effectiveness

and Preferences, In Cross-Disciplinary Advances in

Human Computer Interaction, User Modeling, Social

Computing and Adaptive Interfaces, Eds. Zaphiris,

Panayiotis & Ang, Chee Siang, IGI Global.

Murano, Pietro, Ede, Christopher & Holt, Patrik O'Brian

(2008) Effectiveness and Preferences of

Anthropomorphic User Interface Feedback in a PC

Building Context and Cognitive Load, 10th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 12-16 June 2008. (c) -

INSTICC.

Murano, Pietro, Gee, Anthony & Holt, Patrik O'Brian

(2007) Anthropomorphic Vs Non-Anthropomorphic

User Interface Feedback for Online Hotel Bookings,

9th International Conference on Enterprise

Information Systems, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, 12-

16 June 2007. (c) - INSTICC.

Murano, Pietro, Malik, A. & Holt, P. O. (2009) Evaluation

of Anthropomorphic User Interface Feedback in an

Email Client Context and Affordances, 11th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems, Milan, Italy, 6-10 May. (c) - INSTICC.

Nass, C. and Brave, S. (2005) Wired for Speech How

Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer

Relationship, The MIT Press.

Prendinger, H., Ma, C. and Ishizuka, M. (2007) Eye

Movements as Indices for the Utility of Life-Like

Interface Agents: A Pilot Study, Interacting With

Computers, 19, 281-292.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

44