ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

State of the Art and Challenges

Jorge Cordeiro Duarte and Mamede Lima-Marques

Centre for Research on Architecture of Information, University of Brasilia, Campus, Brazilia, Brazil

Keywords:

IS, IT, Framework, Strategies, EIA, EA, Organizations.

Abstract:

This paper analyzes current approaches for Enterprise Architecture (EA). Current EA objectives, concepts,

frameworks, models, languages, and tools are discussed. The main initiativesand existing works are presented.

Strengths and weaknesses of current approaches and tools are discussed, particularly their complexity, cost and

low utilization. A EA theoretical framework is provided using a knowledge management approach. Future

trends and some research issues are discussed. A research agenda is proposed in order to reduce EA complexity

and make it accessible to organizations of any size.

1 INTRODUCTION

In current economic and business context, organiza-

tional processes and systems need to be constantly

reviewed and updated to keep pace with market de-

mands and technology development. The Enterprise

Architecture (EA) has emerged as a ”tool” for devel-

oping and managing organizational elements provid-

ing the instruments for agility in planning and change.

It is not just a matter of IT, as many believe, but a mat-

ter of knowledge about organization.

Enterprise architecture is a promise for organiza-

tions efficiency, but it is still a confusing concept.

Since its beginning, many heterogeneous architecture

proposals have been developed. They are often over-

lapping approaches and the underlying concepts are

not explicitly defined. Proposals are often complex

and their benefits cannot be perceived by users, cre-

ating obstacles for its correct understanding in indus-

try and finally its acceptance and use. The lack of a

generally agreed terminology in this domain is also a

bottleneck for its efficient application.

The aim of this paper is to analyze the state of the

art of EA, identifying and evaluating the key concepts

and approaches, and propose a theoretical framework

and a research agenda to clarify concepts, define

scope and expand the use of EA. Section 2 presents

the main definitions, concepts and approaches found

in the literature. Section 3 identifies the scope, do-

main areas, elements and EA fundamentals as a dis-

cipline. Section 4 details the main theoretical ap-

proaches. Section 5 analyzes the current practices,

tools and organizational structures. The analysis of

the approaches and trends are presented in section 6.

A research Conclusions and agenda to EA are pre-

sented in Section 7.

2 ENTERPRISE

ARCHITECTURE:

DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTS

Definitions of terms related to EA such as enterprise,

organization, information, knowledge, organizational

elements and domains, models, architecture, informa-

tion Architecture are first given in order to help under-

standing EA Concepts. Then, enterprise architecture

definition, objectives and elements are presented.

2.1 Enterprise Architecture Related

Terms Definitions and Concepts

EA is a kind of architecture, focused on informa-

tion about enterprise domains and its elements. It

deals with information to generate knowledgethrough

models. Following are presented necessary defini-

tions of each one of these terms.

Enterprise. According to ISO 15704 (ISO, 2000), an

101

Cordeiro Duarte J. and Lima-Marques M. (2010).

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE - State of the Art and Challenges.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Information Systems Analysis and Specification, pages

101-112

DOI: 10.5220/0002970001010112

Copyright

c

SciTePress

enterprise is one or more organizations sharing a def-

inite mission, goals and objectives to offer an output

such as a product or a service. This broad definition

covers the extended enterprise (EE) and virtual enter-

prise (VE) (Vernadat, 2007). EE is a concept which

identifies long term integration of suppliers and cus-

tomers. The idea is to provide the central node with

all materials, skills, competencies, knowledge and ca-

pabilities it requires at the right time. Material flows

are usually optimized in just-in-time (JIT) mode. This

is the case of the car industry, aerospace industry,

naval industry, semiconductor industry, etc. VE has

a dynamic and less stable nature than the extended

enterprise. The idea is to put together capabilities and

competencies coming from different enterprises but

no node in the network plays a central role. This is a

cluster or temporary association of existing or newly

created business entities offered by several companies

to form a new viable business entity to satisfy a timely

market need. An example has been the company that

built the Channel Tunnel in Europe (now dismantled)

(Vernadat, 2007).

Organization. Organization is an entity, public or

private, that exists to provide specific services and

products to its customers, serving a purpose of its

owners, performing functions in a structure that re-

sponds to external and internal stimuli (Rood, 1994).

Data. Data is a representation of concepts or other

entities, fixed in or on a medium in a form suitable

for communication, interpretation, or processing by

human beings or by automated systems (Wellisch,

1996). Data is a real thing, a sensory stimulus that we

perceive through the senses, a thing perceived, seen,

felt, heard (Zins, 2007).

Information. Information is the change determined

in the cognitive heritage of an individual (Morris,

1938). Information always develops inside of a cog-

nitive system, or a knowing subject. It is an abstrac-

tion that represents something meaningful to some-

one through text, images, sound or animation (Setzer,

2001).

Knowledge. Knowledge is a fluid mix of experience,

values, contextual information and insights that pro-

vides a framework for evaluating and incorporating

new experiences and information (Horibe, 1999). In-

side Knowledge are faced consciousness and object,

subject and object. The Dualism of subject and object

belongs to the essence of knowledge (Hessen, 2003).

Organizational Element. According to (Kuras,

2003) organizations are complex systems because

they are composed of multiple elements and relations.

The main parts or elements that enable an organiza-

tion to attain its objectives are the principles, strate-

gies, people, units, locations, budgets, functions, ac-

tivities, services, applications, systems and infrastruc-

ture (Schekkerman, 2009b).

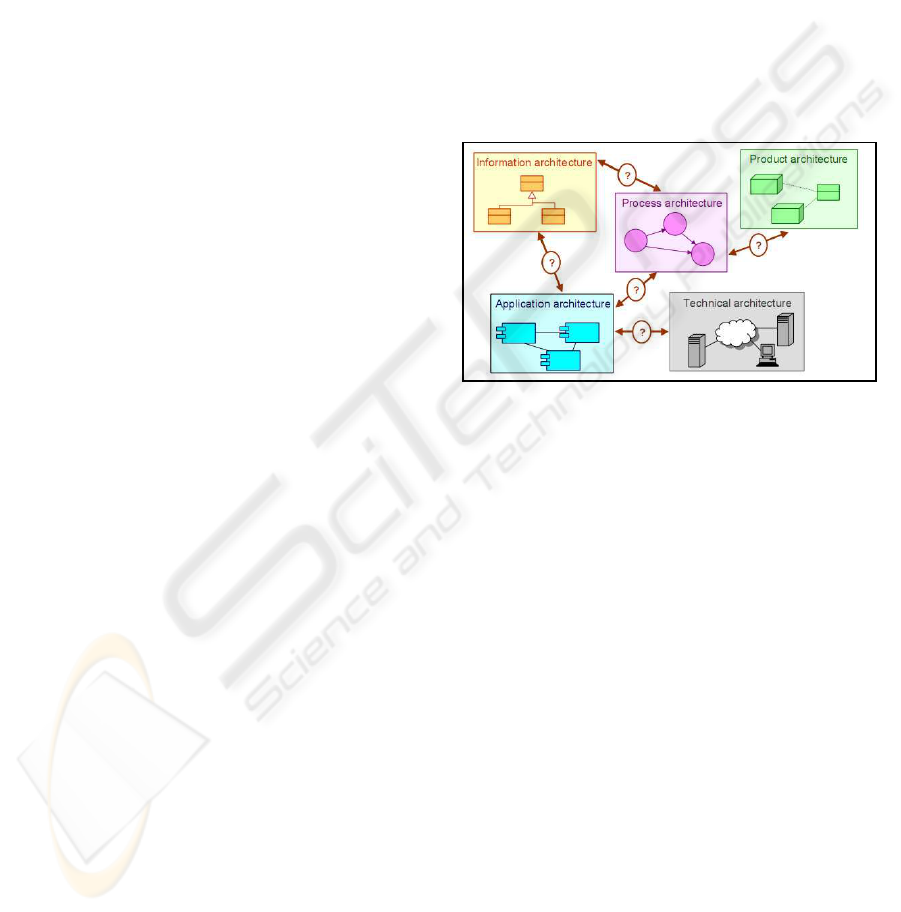

Organizational Domain. The various organizational

elements are grouped into domains of specialized

knowledge. Kettinger identifies six domains of study

of the organization: management, information tech-

nology, processes, structure and people (Kettinger

et al., 1997). The method ArchiMate (Lankhorst,

2005) also proposes five domains: products, pro-

cesses, information, applications and technology, as

shown in Figure 1. Each one of these domains is com-

posed of a diverse community that shares a specific

language (Guizzardi, 2005).

Figure 1: Organizational Domains (Lankhorst, 2005).

Models. A model is an abstraction of reality accord-

ing to a certain conceptualization (Guizzardi, 2005).

Once represented as a concrete artifact, a model can

support communication, learning and analysis about

relevant aspects of the underlying domain. Models

can be formal or informal. Formal models have de-

fined structure and semantics and can be read by the

computer, such as ontologies. Informal models are in-

formation without defined structure, used to express

things or concepts freely (Bernus, 2003). Models can

be conceptual or detailed, static or dynamic. Con-

ceptual models show elements, concepts and relation-

ships, such as ontologies. Detailed models show de-

tails of the composition of the element under study.

Dynamic models show a flow of relations between

objects or changes in the state of the object (Butler,

2000). Models can be expressed as text, graphics or

formulas (Vergidis et al., 2008). Models can express

different levels of details, form physical to social ones

as proposed by Stamper (2000) in figure 2.

Architecture. The central idea of architecture is

to represent or model (in abstraction) an orderly ar-

rangement of the components that make up a sys-

tem in analysis and the relationships or interactions of

these components (Rood, 1994). Architecture deals

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

102

with the structure of important things (buildings, sys-

tems or organizations) and their components and how

these components are combined to achieve a partic-

ular purpose (open Group, 2009). Architecture can

be descriptive, describing what exists, or prescriptive,

showing something wanted and that still does not not

exists (Hoogervorst, 2004).

Figure 2: Semiotic Ladder (Stamper et al., 2000).

Information Architecture. The term Information

Architecture (IA) was first used by (Wurman, 2000).

Wurman’s vision is derived from his training as an ar-

chitect and his main purpose is to extend the key con-

cepts of organizing spaces, developed in architecture,

for informational spaces. The term was popularized

by (Morville and Rosenfeld, 2006) who define infor-

mation as the structural design of shared information

environments. AI has been widely studied in academy

and is the subject of several master theses (Macedo,

2005; de Siqueira, 2008). According to Macedo the

purpose of Information Architecture is to enable the

effective flow of information through the design of in-

formation environments.

2.2 Enterprise Architecture Definitions

There are many definitions for EA. The name of disci-

pline, itself, may vary being referred to as Enterprise

Architecture (EA) (Zachman, 1987) or Enterprise In-

formation Architecture (EIA) (Cook, 1996). Exam-

ples of EA definitions found in literature: An ab-

straction of the main elements of the organization and

their relationships (Vernadat, 1996); Define the vari-

ous elements that make up an organization and how

they relate and establish the principles and guidelines

governing their design and evolution over time (open

Group, 2009); A coherent set of principles, methods

and models used in the design and construction of the

structure, processes, systems and infrastructure of an

organization (Lankhorst, 2005); Blueprints which de-

fine a complete and systematic position of the current

and desired organizational environment (Schekker-

man, 2009a); A description of a complex system (the

enterprise) at a point in time (Burke, 2006); The struc-

ture of components, their relationships, and the prin-

ciples and guidelines governing their design and evo-

lution over time (DoD, 2007).

2.3 Enterprise Architecture Objectives

Some examples of EA objectives found in the liter-

ature: EA intends to model, analyze and communi-

cate the organization. The benefits of EA are the

knowledge infrastructure for reporting and analysis

by all stakeholders and the possibility of designing

new conditions in an organized manner (Lankhorst,

2005). EA is not only an instrument for strategic plan-

ning of IS/IT planning but also other business func-

tions, such as compliance control, continuity plan-

ning and risk management (Winter and Schelp, 2008).

The objectives of the EA are risk and compliance

control, project and organizational programs manage-

ment, portfolios of IT management and integration

between business and IT (Schekkerman, 2009a). Ac-

cording to (Rood, 1994) an EA, as a whole, is used in

a number of different ways to guide, direct, and man-

age an enterprise: Is a basis for decision making and

planning; Governs the identification, selection and de-

velopment of standards; is the mechanism for man-

aging change within the enterprise; Enables effective

communication about the enterprise.

2.4 Enterprise Architecture Elements

To achieve its objectives EA requires several el-

ements. The project IFIP-IFAC proposed an on-

tology of these elements called GERAM (General-

ized Enterprise-Reference Architecture and Method-

ology) (IFIP-IFAC, 1999). This ontology identifies

the following elements in the architecture: concepts,

methodologies, languages, models concepts and con-

structs, reusable templates, modeling tools, reference

models, business modules and operation systems.

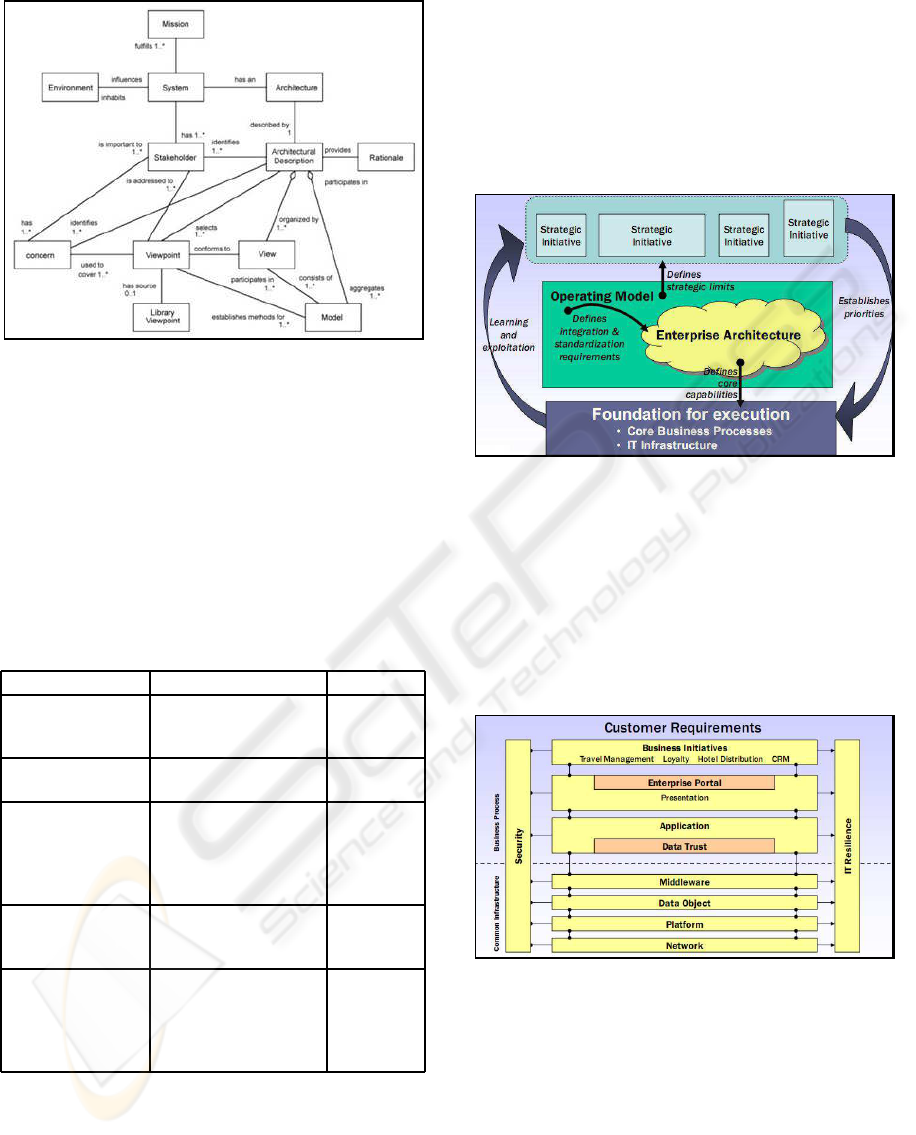

Another ontology proposed for EA is IEEE 1471

recommended practice for architectural description of

software (IEEE, 2000). This proposal has sixteen el-

ements: mission, environment, system, architecture,

stakeholder, architecture description, view, concern,

viewpoint, model, rationale, and library viewpoint as

shown in figure 3. This recommended practice ad-

dresses the activities of creation, analysis and sustain-

ment of architecture software-intensive systems, and

the recording of such architectures in terms of archi-

tectural descriptions.

3 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

APPROACHES AND

FRAMEWORKS

This section suggests a classification for current EA

approaches nas presents the main proposals.

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE - State of the Art and Challenges

103

Figure 3: IEEE-1471 Framework (IEEE, 2000).

3.1 Enterprise Architecture Approaches

Since middle of the 1980s severalproposals of EA ap-

pear. The diverse proposals have different approaches

aiming different objectives. Table 1 shows a clas-

sification of proposals in five approaches: Strategic

EA, enterprise modeling, enterprise modeling meth-

ods and standards, enterprise architecture language

and Information Architecture.

Table 1: Evolution of Technology and System Applications.

Approach Objective Proposal

Strategic EA Blueprints showing

enterprise and tech-

nical infrastructure

(Ross

et al.,

2006)

Enterprise Mod-

eling

Framework of orga-

nizational models

(Zachman,

1987)

Enterprise mod-

eling methods

and standards

Framework, methods

and standards for or-

ganizational models

(open

Group,

2009;

DoD,

2007)

Enterprise archi-

tecture language

Framework and lan-

guage to model ar-

chitectural models

(Lankhorst,

2005)

Enterprise Infor-

mation Architec-

ture Approach

Infrastructure for

modeling the enter-

prise information

(Morville

and

Rosen-

feld,

2006)

3.2 Strategic Enterprise Architecture

According to EA strategic approach, EA should not

be a huge collection of organizational models, but in-

stead, a group of strategic maps (Ross et al., 2006).

To be used strategically, EA has two sides: business

and technology. On the business side it is necessary to

identify organization operational model. This model

defines whether the company is centralized or decen-

tralized and whether its processes are standardized or

not. Once identified this enterprise model of oper-

ation, IT must define the technical architecture that

supports this model. This architecture can extend or

limit organizational strategies as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Strategic EA Conponents (Ross et al., 2006).

This proposal does not need many models, only

those needed to show the main enterprise and tech-

nical components and how they relate to each other.

Ross suggests only a blueprint showing the main ele-

ments of business, application, security and technol-

ogy as shown is figure 5. Whittle and Myrick refer

this approach as EBA (Enterprise Business Architec-

ture) (Whittle and Myrick, 2004).

Figure 5: Strategic EA Metamodel(Ross et al., 2006).

3.3 Frameworks to Enterprise

Modeling

One of the first proposals for EA is Zachman frame-

work which had its first version in 1987 and has been

constantly updated with the latest release in 2008

(Zachman, 1987). Zachman framework proposes or-

ganizational modeling in thirty-six models. These

models are structured in six rows and six columns.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

104

The six columns indicate domains of organization

knowledge and models are related to: Information

(what), Processes (how), People (who), Locations

(where), Time (when) and Reasons (why). The six

lines show level of detail in each domain: Contex-

tual, Conceptual, Logical, Physical, Component and

Instance. Thus, Zachman framework is a matrix and

each cell is a kind of model as shown in figure 6.

Zachman does not propose a methodology nor sug-

gests good practices, only the matrix of models. Many

authors have completed the proposal suggesting lan-

guages to elaborate each model or group of models

(Pereira and Sousa, 2004; Cook, 1996)

Figure 6: Zachman Framework (Correia and Silva, 2005).

3.4 Frameworks, Methods and

Standards to Enterprise Modeling

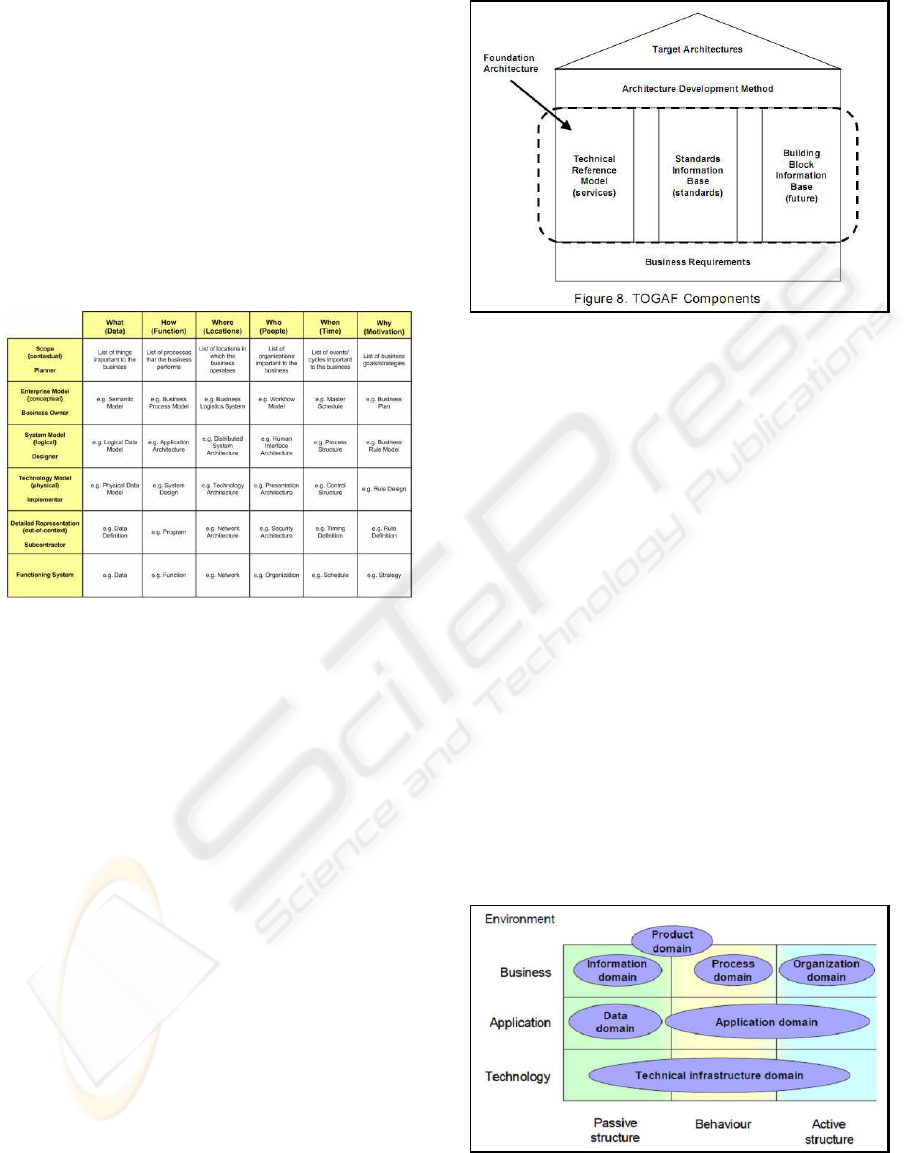

The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF)

is an EA Framework which describes a methodical

process along with a set of supporting tools (open

Group, 2009). There are 3 main components of TO-

GAF: Architectural Development Method(ADM) - a

process used to derive an Enterprise Architecture for

an organization; Enterprise Continuum - a ”virtual

repository” for architectural assets of the organization

(models, patterns and architecture descriptions) and

TOGAF Resource Base - a set of resources, including

guidelines, templates, and background information to

aid in the ADM. The ADM helps to describe how to

develop an Enterprise Architecture through the exam-

ination of business requirements as shown in figure

7. There are nine main areas to help define the Enter-

prise Architecture Preliminary Phase, architecture vi-

sion, Business Architecture, Information Systems Ar-

chitecture, Data Architecture, Applications Technol-

ogy Architecture, Opportunities and Solutions, Mi-

gration Planning Implementation Governance, Archi-

tecture Change Management. The Open Group maps

out how to use the ADM to populate the Zachman

Figure 7: TOGAF Framework (Arbab et al., 2002).

Framework in various steps.

There are other proposals similar to TOGAF com-

bining frameworks with method and guidelines, espe-

cially in the U.S. government. DoDAF is the proposal

of the Department of Defense (DoD, 2007) and the

FEAF is the federal government (FEA, 2007).

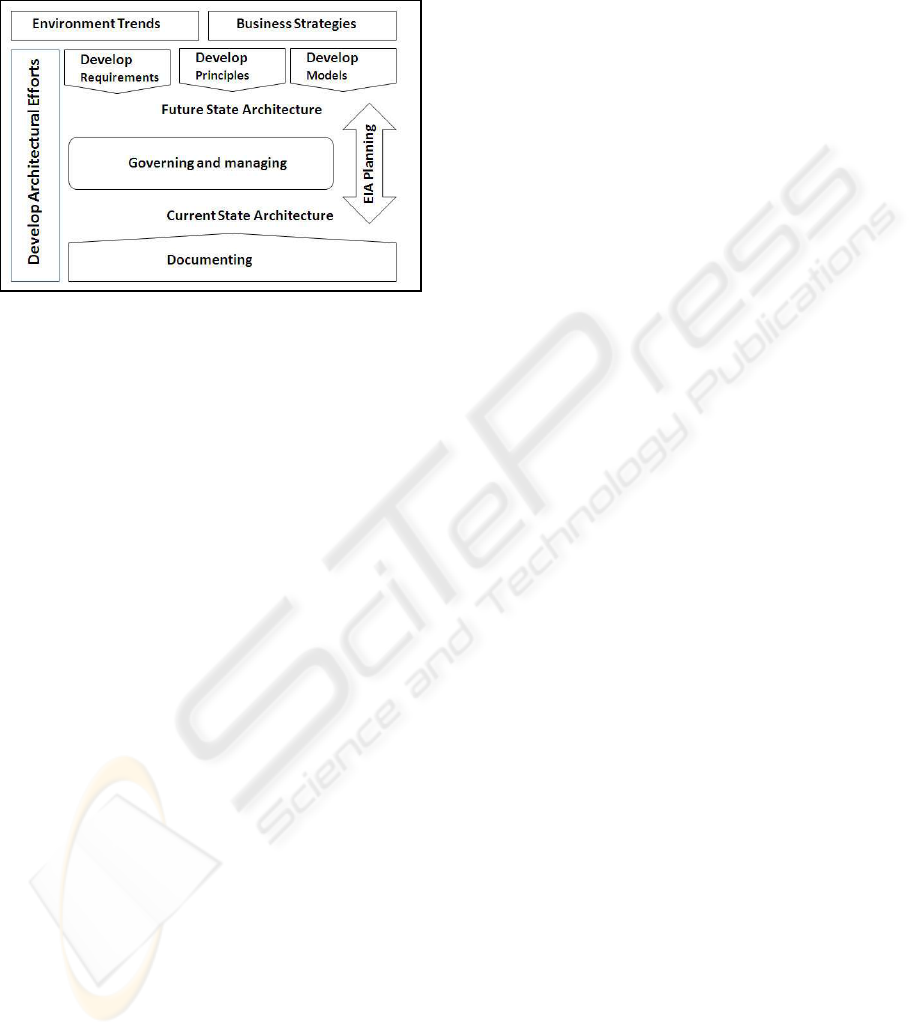

3.5 Enterprise Architecture Language

Archimate proposal (Lankhorst, 2005) was submitted

in 2005 as a result of the project developed at Telem-

atica Institut (now Novay), Netherlands. Archimate is

a matrix like Zachman, but proposes a language and

specific models for EA. The matrix has only 3 rows

and 3 columns as shown in figure 8. The lines indicate

models for business , information and technology and

the columns indicate models in active, behavior, and

passive level. Models in seven domains are suggested

to fill the cells of the matrix: Product; Organization;

Information; Processes; Application; Data and Infras-

tructure. Archimate is now part of The Open Group

line of products.

Figure 8: Archimate Framework (Lankhorst, 2005).

ArchiMate proposesa metamodel for each domain

with a ontology, indicating the elements and relations

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE - State of the Art and Challenges

105

in that domain. Figure 9 shows the ontology for the

business domain.

Figure 9: Archimate Meta Model for Business Domain

(Lankhorst, 2005).

3.6 Information Architecture

The Enterprise Information Architecture (EIA) ap-

proach to EA is an Information Architecture (IA)

approach extension for the organization environment

(Morville and Rosenfeld, 2006). This approach is dif-

ferent of other EA approaches because it does not

consider information systems as the central focus.

Figure 10 shows a proposal where EA, EIA and con-

tent management (CM) approaches working together

1

. The main focus of this alliance is architectural

information identification, classification and delivery

working with semantics, metadata, taxonomies, con-

trolled vocabularies, ontologies and search.

Figure 10: EA and Knowledge Management Efforts (James

Melzer, 2009).

1

www.jamesmelzer.com

4 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

PRACTICE

This section presents a review of the literature about

EA practice, analyzing tools, organizational struc-

tures and strategies.

4.1 Enterprise Architecture Tools

Schekkerman (2009) publishes an extensive annual

survey of the various EA tools in the market. It is

important to note that following Zachman proposal,

the architecture can consist of models from various

domains which can lead to the conclusion that any

modeling tool can be considered as a tool for EA.

This is the focus of Schekkerman analyzes. The study

shows most of the tools meet only part of architecture

domains and no tool is specialized in EA, They pro-

vide resources to make many other things such sys-

tems or processes modeling. There also other reviews

of EA market analyzing Strengths and Weakness of

theirs resources (Ernst et al., 2006). Research in-

stitutes, such as Gartner and Forrester, also publish

annual reports assessing the tools to EA. Both con-

sider that only six or seven companies meet the re-

quirements for an EA tool. These requirements are:

resources to model the various domains, specific re-

sources to model architecture and identify relations

between models, support for the main frameworks, re-

sources for managing projects, resources for publish-

ing on the Web, collaboration resources and a reposi-

tory for storing and retrieving models. The main com-

panies that offer tools with these requirements are:

IBM (System Architect and Rational)

2

, IDS Scheer

(ARIS tools)

3

, Metastorm

4

, Troux Technologies

5

and Alphabet

6

. Figure 11 shows a screen of Sys-

tem Architect tool where relations between models

are presented.

None of these tools was born in EA market and

none is dedicated solely to EA. Some are special-

ized in modeling systems, such as IBM tools, and

others are specialized in modeling processes such as

ARIS. Figure 12 shows the diverse functions offered

in IBM Telelogic solution. Enterprise architecture is

one among several resources it offers.

2

http://www-01.ibm.com/software/rational/

3

http://www.ids-scheer.com/index.html

4

http://www.metastorm.com/

5

http://www.troux.com/

6

http://www.alfabet.com/

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

106

Figure 11: Models Relations in System Architect Software.

Figure 12: Telelogic software Components.

4.2 Enterprise Architeture Reference

Models

There are a great number of Operation Reference

(OR) Frameworks that can serve as templates, rad-

ically simplifying the creation or improvement of

architectural models. The Supply Chain Council’s

SCOR (Suply Chain Operational Framework)

7

and

the Tele management Forum’s eTOM (enhanced Tele-

com Operations Map)

8

are proposal in specific areas

of suply chain and telecom. Figure 13 shows a tem-

plate of eTOM that shows organizational architecture

domains and its relation such as strategy, infrastruc-

ture, product, operations, and enterprise management.

Another reference model that can be used to

build specific model is the OMG Business motiva-

tion model (BMM) that details the element of mod-

eling organizational objectives and goals. Many au-

thors have published works suggesting models of en-

terprise ontologies which can be used as a skeleton

for building a specific architecture model, saving time

7

http://www.supply-chain.org/

8

http://www.tmforum.org/BusinessProcessFramework/

1647/home.html

Figure 13: eTOM reference model.

and bringing consistence (Jussupova-Mariethoz and

Probst, 2007; Emery, 2007).

4.3 Enterprise Architeture Strategies

Many EA programs do not succeed because they are

not well implemented. It is recommended to to imple-

ment an EA program in five steps: Initiate the effort;

Describe where we are; Identify where we would like

to be ;Plan how to get there; Implement the architec-

ture (Boster et al., 2000).

Initiate the Effort. Develop an architecture frame-

work;Create readiness for architecture Build the ar-

chitecture team; Identify and influence stakeholders;

Encourage open participation and involvement; Re-

veal discrepancies between current and desired state.

Describe where we are. Characterize the baseline

architecture; Make it clear to everyone why change is

needed.

Identify where we would Like to Be. Develop

the target architecture; Communicate valued features;

Energize commitment; Create a plan for transition ac-

tivities.

Plan how to Get there. Develop the transition plan;

Execute the target architecture Communicate the tran-

sition plan; Establish sound management structure;

Build support for the architect.

Implement the Architecture. Maintain/enhance the

target architecture; Develop new competencies and

skills; Reinforce architecting practices

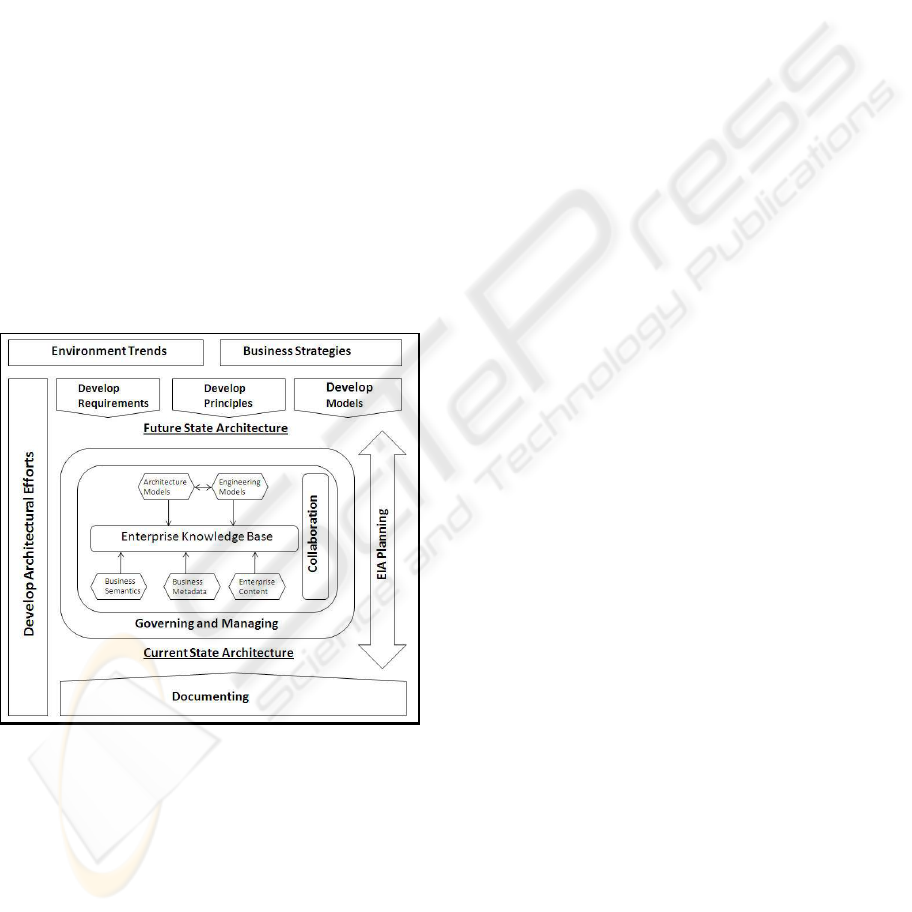

This plan of action is structured in many method-

ologies such as EA Gartner Framework (Burke,

2006), shown in figure 14. First, a architectural ef-

fort must be implemented. Then, it is necessary to

document a current situation and design an expected

one. All these efforts must be based on principles and

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE - State of the Art and Challenges

107

requirements guided by business strategies and envi-

ronment trends. A transition plan must be made to

reach desired state. All the process must be managed

and governed.

Figure 14: Gartner Framework (Burke, 2006).

4.4 Organizational Structures for

Enterprise Architeture

To reach its goals EA must have an organizational

structure with a group responsible for it (Harmon,

2003). (Rosenfeld, 2007) proposes a structure with an

EA board and an EA operational management team.

This team must have a central staff and also special-

ists distributed in local departments that contributes

to EA contents. The central staff does not generate

content. The central staff must implement and man-

age an infrastructure to EA and identify and publish

EA policies and guidelines. As Rosenfeld states, EA

is a mix of users, context and context (Rosenfeld,

2007). EA community is composed by users and con-

tent generators that are also users. Each user needs a

specific vision of architectural elements. Each con-

tent contributor deals with a specific content level.

It is a function of EA staff to know who does con-

tent and who needs information. The enterprise Ar-

chitect is the main professional for EA. Given the

interdisciplinary nature of EA, the enterprise Archi-

tect must have a general knowledge of various disci-

pline (Strano and Rehmani, 2007). These discipline,

among others, are business strategy, financial man-

agement, organizational dynamics, business process

design, and information technology.

The National Association of State Chief Informa-

tion Officers (NASCIO) (Nascio, 2003) proposes a

maturity model for assessing EA organizational ap-

proachesmaturity (EAMM). Accordingto this assess-

ment methodology, EA comprises five levels of ma-

turity: The lowest level is when there is no EA ap-

proach and the highest one is when organization has

departments working together as contributors to the

architecture and its processes and metrics assess the

effective contributions of EA.

4.5 EA Practice

Current Research on EA practice does not present

a positive situation. A survey published by Gartner

(Burke, 2006) identifies that only 25% of EA initia-

tives can be considered active and mature. 50% of

them take 2 steps forward and 1 step back and 25%

have failed repeatedly. An investigation of perception

and practice of EA found that IT professionals still

do not perceive EA as an organizational effort, but an

IT initiative which indicates that EA is not properly

implemented (Kappelman and Salmans, 2007). The

same survey shows that the identification of require-

ments is still a great challenge in information systems

development which shows the necessity of change in

systems development processes. Another study iden-

tified that only 6% of organizations have an appropri-

ate degree of maturity in the modularization of its in-

formation systems (Ross et al., 2006). The literature

is plentiful in perceptions that EA, though admittedly

to be an important tool, it is not a standard practice in

organizations, mainly considering medium and small

ones (Vernadat, 2007).

5 ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT

EA APPROACHES

This section providesan assessment of each of the five

types of approaches outlined in previous review. For

each approach strengths and weaknesses are analyzed

and recommendations on their use are proposed.

Strategic EA. The strength of this approach is allow-

ing organization to identify the essence of business

and mode of operation and combine the best tech-

nology strategy to meet these strategic requirements.

This approach addresses only top management and

does not meet operation management requirements.

It is essencial to map business and technology strate-

gies. It Must be used in conjunction with other ap-

proaches.

Enterprise Modeling. The strength of this approach

is allowing organization to identify business and tech-

nology engineering in a wide variety of models from

various domains and in different levels of detail. It is

considered architecture because it lays out an archi-

tectural classification of models. It is an approach too

broad that makes technical staff confused. IT does

not indicate who makes models and how. It does

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

108

not separate efficiently frontiers between architecture

and engineering. Use this approach determining this

frontier, indicating when, why, how and by whom the

models must be made. The architectural models can

be used for navigation in the structure of models start-

ing with the conceptual vision (architecture) to reach

the more detailed level (engineering).

Enterprise Modeling Methods and Standards. The

power of this approach is to allowing organization to

identify business and technology architecture with a

method and best practices. It is useful because lays

out the architectural classification of models and de-

termines how, why and who should develop the mod-

els. It is an approach also too broad that makes the

technical staff confused, because there is no clear

boundary between engineering and architecture activ-

ities. Use this approach after clarifying these bound-

aries.

Enterprise Architecture Language. The strength of

this approach is to offer a specific language for ar-

chitecture models. It defines clearly EA boundaries

suggesting only architectural modeling trough meta-

models. The approach does not indicate methods and

best practices. To be used in conjunction with other

approaches.

Enterprise Information Architecture Approach.

The strength of this approach is to provide an inte-

grated view of organizational information fleeing the

technological paradigm. The approach established an

infrastructure for organizational knowledge gathering

content, models, semantics and metadata. It organizes

organizational information and serves different audi-

ences. It can become complex to manage, because

joins together many different concepts such as IA,

EA, ECM and enterprise collaboration. To be used in

a broader initiative of EIA, linking all organizational

information in only one effort.

6 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

CHALLENGES

EA has many proposal with many approaches. Why,

then, many organizationsfail to implement the EA ap-

proach. Ambler (Ambler, 2009) tries to explain the

reasons for failure in the efforts of EA:

• There isn’t an enterprise architecture effort.

• Skewed focus.

• Project teams don’t know the enterprise architec-

ture exists.

• Project teams don’t follow the enterprise architec-

ture.

• Project teams don’t work with the enterprise ar-

chitects.

• Outdated architecture.

• Narrowly focused architecture models.

• Dysfunctional ”charge back” schemes.

• A “do all this extra work because it’s good for the

company” attitude.

EA, considering the breadth of its goals, undoubt-

edly has many challenges, as identified by Khoury

(Khoury, 2007):

• Abstraction Challenge: EA models need to be

in an suitable level of abstraction. Details must

satisfy uficientes para satisfazer aos diversos in-

teressados;

• Cognition Challenge: models need to be repre-

sented in a language that is intelligible to all stake-

holders;

• Collaboration Challenge: EA needs the cooper-

ation of other communities to develop and main-

tain current models of the architecture;

• Communication Challenge: models of the archi-

tecture must be communicated to all stakeholders;

engagementchallenge: the entire organization can

benefit from models of architecture and many can

help develop them. The challenge is the involve-

ment of all;

• Update Challenge: organizations are very dy-

namic and the information contained in the mod-

els can quickly downgrade.

7 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This section presents a theoretical framework that

comprises the main topics discusses in this review.

Analyzing main current EA approaches it is easy to

visualize that they came from technology. It is also

clear that no approach is complete to be used in a

isolated fashion. It is necessary to accommodate the

various approaches in a single platform. Almost all

current approaches make a great confusion between

architecture and engineering. No approach solve all

challenges EA have. For this reason, many authors

claim that the EA is not yet mature. We surely need a

new paradigm. EA surely is and must be considered

an organizationalEnterprise Information Architecture

approach. EA must be a index for technology and for

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE - State of the Art and Challenges

109

business. Everybody in organization must have ac-

cess to architectural information that leads to opera-

tional information. This information will be available

only if key people in organization contribute as in-

formation architects in an ongoing and collaborative

manner. With this focus, EA needs fundamentals, the-

ories and tools more appropriate than those currently

available.

We propose in figure 15, an EA theoretical frame-

work which consolidates current theory and incorpo-

rates a EIA approach to EA. This framework incorpo-

rates the necessary IA elements to EA and vice versa.

In our approach, EA must work in conjunction with

Content management and EIA efforts contribution

with artifacts and using a organizational knowledge

base. It makes no sense EA efforts to manage models

only. Words are models to. Models are knowledge as

all other organizational content. Organizational con-

tent features important information for models and

vice versa. Organizational contents must be associ-

ated with models. A marketing campaign has impor-

tant information for business and needs business in-

formation. It makes sense to have two worlds of in-

formation.

Figure 15: A KM-EA Framework.

8 CONCLUSIONS AND

RESEARCH AGENDA

This paper presented a review of current literature on

concepts and approaches to EA, contributing to a bet-

ter understanding of the state of the art and the chal-

lenges of this field of research and practice. Analyz-

ing EA research and looking at EA practice it is easy

to see that, even though EA is seen with optimism

on a medium and long run, the current reality is not

good. Most of the professionals who could be using

the existing proposals consider approaches still con-

fusing and complex and tools much expensive. It is

not clear for systems analysts the boundary between

modeling a system and modeling an application ar-

chitecture. It is not clear for business analyst the dif-

ference between a process model and an a business

architecture model. It is not clear to both profession-

als who should make engineering models and archi-

tecture ones.

If EA boundaries are not clear to professionals,

they are not clear to executives either. So, EA initia-

tives are not properly structured. A poorly structured

EA initiative is a sure failure. EA is certainly a com-

plex initiative considering the existing approaches.

The expectation is that over time it becomes mature

to be implemented in a less complex manner. For this

to happen it is necessary, above all, better approaches

and more specialized and affordable tools.

A new agenda of EA research is needed. Research

must clarify EA boundaries, and provide unique foun-

dations and theories. EIA approaches must come to

EA and so research must come in this direction. EA

tools must be specialized in EA, not a extension of

other objetives. EA methods and tools must be pos-

sible of customization to organization needs simplify-

ing its use. EA, EIA and CM tools must join efforts to

build a tool which allows access to all organizational

information and content with security. This new tool

must be able to help collaboration between people in

order to increase continually information and mod-

els available. It must have semantic and metadata re-

sources in order to make easy classifying and access-

ing all kinds of models and contents. EA, EIA and

CM, together, can help organizations make architec-

ture come true.

REFERENCES

Ambler, S. W. (2009). Agile enterprise architecture.

Arbab, F., Bonsangue, M., Scholten, J. G., , Iacob, M.-E.,

Jonkers, H., Lankhorst, M., Proper, E., and Stam, A.

(2002). State of the art in architecture frameworks and

tools. Technical report, Telematic Intitute - Nether-

lands.

Bernus, P. (2003). Enterprise models forenterprise architec-

ture and iso 9000:2000. Annual Reviews in Control,

27(2):211–220.

Boster, M., Liu, S., and Thomas, R. (2000). Getting the

most from your enterprise architecture. IT Profes-

sional, 2(4):43–1.

Burke, B. (2006). Enterprise architecture: New challenges

- new approaches. Report, Gartner Group, New York.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

110

Cook, M. (1996). Building Enterprise Information Archi-

tectures: Reengineering Information Systems. Pren-

tice Hall, New York.

Correia, A. and Silva, M. M. D. (2005). Modeling Services

in Information Systems Architectures. Springer, New

York.

de Siqueira, A. H. (2008). A logica e a linguagem como

fundamentos da arquitetura da informacao. Masther

theses, Faculdade de Economia, Administracao, Con-

tabilidade e Ciencia da Informao e Documentacao,

Universidade de Brasilia, Brasilia.

DoD (2007). Dod architecture framework version 1.5.

Technical report, Washington DC.

Emery, D. (2007). Frameworks in iso-iec 42010.

Ernst, A. M., Lankes, J., Schweda, C. M., and Witten-

burg, A. (2006). Tool support for enterprise archi-

tecture management - strengths and weaknesses. In

EDOC ’06: Proceedings of the 10th IEEE Interna-

tional Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Con-

ference, pages 13–22, Washington, DC, USA. IEEE

Computer Society.

FEA (2007). Fea consolidated reference model document

version 2.3. Technical report, OMB - Office of Man-

agement and Budget - USA, Washington.

Guizzardi, G. (2005). Ontological foundations for struc-

tural conceptual models. Master’s thesis, Universiteit

Twente.

Harmon, P. (2003). Developing an enterprise architecture.

Technical report, www.Bptrends.com.

Hessen, J. (2003). Teoria do Conhecimento. Martins

Fontes, Sao Paulo.

Hoogervorst, J. (2004). Enterprise architecture enabling in-

tegration, agility and change. International Journal of

Cooperative Information Systems, 13(2):213–233.

Horibe, F. (1999). Managing Knowledge Workers: New

Skills and Attitudes to Unlock the Intellectual Capital

in Your Organization. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

IEEE (2000). Ieee-std-1471-2000 recommended practice

for architectural description of software-intensive sys-

tems. Technical report.

IFIP-IFAC (1999). Geram:generalised enterprise reference

architecture and methodology. Technical report.

ISO (2000). Iso 15704, industrial automation systemsre-

quirements for enterprise-reference architectures and

methodologies. Technical report, ISO.

Jussupova-Mariethoz, Y. and Probst, A.-R. (2007). Busi-

ness concepts ontology for an enterprise performance

and competences monitoring. Computers in Industry,

58(2):118–129.

Kappelman, L. A. and Salmans, B. (2007). Information

management practices survey 2007 preliminary re-

port: The state of ea: Progress, not perfection.

Kettinger, W. J. T., C., J. T., and Guha, S. (1997). Busi-

ness process change: A study of methodologies, tech-

niques, and tools. MIS Quarterly, 21(1).

Kuras, M. (2003). Enterprises as complex systems. The

edge, 7(2).

Khoury, G. R. (2007). A Unified Apporach to Enterprise

architecture Modeling. PhD thesis, Faculty of Infor-

mation Technology, Sydney.

Lankhorst, M. (2005). Enterprise architecture at work -

Modelling, communication and analysis. Springer-

Verlag, Heilderberg.

Macedo, F. L. O. (2005). Arquitetura da informacao: as-

pectos epistemologicos, cientficos e praicos. Mas-

ther theses, Faculdade de Economia, Administracao,

Contabilidade e Ciencia da Informao e Documenta-

cao, Universidade de Brasilia, Brasilia.

Morris, C. W. (1938). Foundations of the Theory of Signs.

University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Morville, P. and Rosenfeld, L. (2006). Information Archi-

tecture fot the Word Wide Web. OReilly, Sebastopol.

NASCIO (2003). Nascio enterprise architec maturity

model. Technical report, National Association of State

Chief Information Officers.

open Group, T. (2009). Togaf - version 9 enterprise edition.

Technical report, San Francisco.

Pereira, C. M. and Sousa, P. (2004). A method to define an

enterprise architecture using the zachman framework.

2004:1366–1371.

Rood, M. (1994). Enterprise architecture: definition, con-

tent, and utility. In Third Workshop on Enabling

Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enter-

prises, pages 106–111, New york. IEEE.

Rosenfeld, L. (2007). Enterprise information architecture:

Because users do not care about your org chart.

Ross, J. W., Weill, P., and Robertson, D. (2006). Enterprise

Architecture As Strategy: Creating a Foundation for

Business Execution. Harvard Business School Press,

Boston.

Schekkerman, J. (2009a). Enterprise architecture tool se-

lection guide. Technical report.

Schekkerman, J. (2009b). Enterprise architecture valida-

tion.

Setzer, V. W. (2001). Dado, Informacao, Conhecimento e

Competencia. Editora Escrituras, Sao Paulo.

Stamper, R., Liu, K., Hafkamp, M., and Ades, Y. (2000).

Understanding the roles of signs and norms in organ-

isations - a semiotic approach to information systems

design. Journal of Behaviour & Information Technol-

ogy, 19.

Strano, C. and Rehmani, Q. (2007). The role of the enter-

prise architect. Information Systems and E-Business

Management, 5(4):379–396.

Vergidis, K., Tiwari, A., and Majeed, B. (2008). Business

process analysis and optimization: Beyond reengi-

neering. IEEE Transactions on systems, man and cy-

bernetics, 38(1).

Vernadat, F. (1996). Enterprise Modeling and Integration:

Principles and Applications. Springer, New york.

Vernadat, F. (2007). Interoperable enterprise systems: Prin-

ciples, concepts, and methods. Annual Reviews in

Control, 31(1):137–145.

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE - State of the Art and Challenges

111

Wellisch, H. (1996). Abstracting, indexing, classification,

thesaurus construction: A glossary. American Soci-

ety of Indexers, Port Aransas, TX.

Whittle, R. and Myrick, C. B. (2004). Enterprise Business

Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and

Results. CRC, New York.

Winter, R. and Schelp, J. (2008). Enterprise architecture

governance: the need for a business-to-it approach. In

Proceedings of the ACM symposium on Applied com-

puting, pages 548–552, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Wurman, R. S. (2000). Information Anxiety. Hayden/Que,

New York.

Zachman, J. (1987). A framework for information systems

architecture. IBM Systems Journal, 26(3).

Zins, C. (2007). Conceptual approaches for defining data,

information, and knowledge: Research articles. Jour-

nal of the American Society for Information Science

and Technology, 58(4):479–493.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

112