UNDERSTANDING ACCESS CONTROL CHALLENGES

IN LOOSELY-COUPLED MULTIDOMAIN ENVIRONMENTS

Yue Zhang and James B. D. Joshi

Information Science Department, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, U.S.A.

Keywords: Access Control, Loosely-Coupled, Multidomain Environments, Policy Integration, RBAC.

Abstract: Access control to ensure secure interoperation in multidomain environments is a crucial challenge. A

multidomain environment can be categorized as tightly-coupled or loosely-coupled. The specific access

control challenges in loosely-coupled environments have not been studied adequately in the literature. In

this paper, we analyze the access control challenges specific to loosely-coupled environments. Based on our

analysis, we propose a decentralized secure interoperation framework for loosely-coupled environments

based on Role Based Access Control (RBAC). We believe our work takes the first step towards a more

complete secure interoperation solution for loosely-coupled environment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Access control poses a significant challenge to

ensure that data is exchanged and shared in a secure

way in a multidomain environment. We refer to this

as the secure interoperation problem (Gong, 1996).

In a typical scenario, a multidomain environment

may involve a small number of organizations closely

related to each other. They typically collaborate for a

common purpose and interoperations among them

need to be predefined to complete the common task.

We refer to such multidomain environments as

tightly-coupled environments. With the recent

advances in distributed systems and networking

technologies, such small and tightly-coupled

environments can not satisfy the fast growing

interoperation needs. Dynamic interoperations

among very large number of distributed domains

become not only feasible but also increasingly

popular. We refer to such an environment as the

loosely-coupled environment.

In the literature, the access control challenges in

tightly-coupled environments have been studied

extensively and they in general use global policy

based approaches (Gong, 1996; Shafiq, 2005). The

specific access control challenges in a loosely-

coupled environment, however, have not been

studied adequately in the literature. In this paper, we

focus on analyzing and identifying the access control

challenges in loosely-coupled environments. Based

on our analysis, we propose a decentralized secure

interoperation framework for loosely-coupled

environments. We believe this is the first step

towards solving all those challenges we identify.

Assuming that each individual domain employs

RBAC and the hybrid hierarchy, the proposed

framework consists of three components: Domain

Discovery, Trust Management, and Policy

Integration.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We

discuss the background of our work in Section 2. We

analyze access control challenges in loosely-coupled

environments in Section 3. The proposed secure

interoperation framework is described in Section 4.

We conclude our work in Section 5.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 RBAC and Hybrid Hierarchy

In RBAC (Ferraiolo, 2001), users and permissions

are associated through roles. Any user assigned to a

role can acquire the permissions assigned to that

role. One of the most distinguished features of

RBAC is the role hierarchy, defining inheritance

semantics over roles. Joshi et al. have proposed

hybrid hierarchy containing the following three

relations (Joshi, 2002): permission-inheritance-only

(I-relation, ≥

i

), activation-inheritance-only (A-

356

Zhang Y. and B. D. Joshi J. (2010).

UNDERSTANDING ACCESS CONTROL CHALLENGES IN LOOSELY-COUPLED MULTIDOMAIN ENVIRONMENTS.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Information Systems Analysis and Specification, pages

356-361

DOI: 10.5220/0002976903560361

Copyright

c

SciTePress

relation, ≥

a

), and the combined permission-

inheritance and activation hierarchy (IA-relation, ≥).

Semantically, x ≥

i

y means that permissions available

through y are also available through x; x ≥

a

y means

that any user who can activate x can also activate y;

and x ≥

y means that permissions available through j

are available through s and users who can activate s

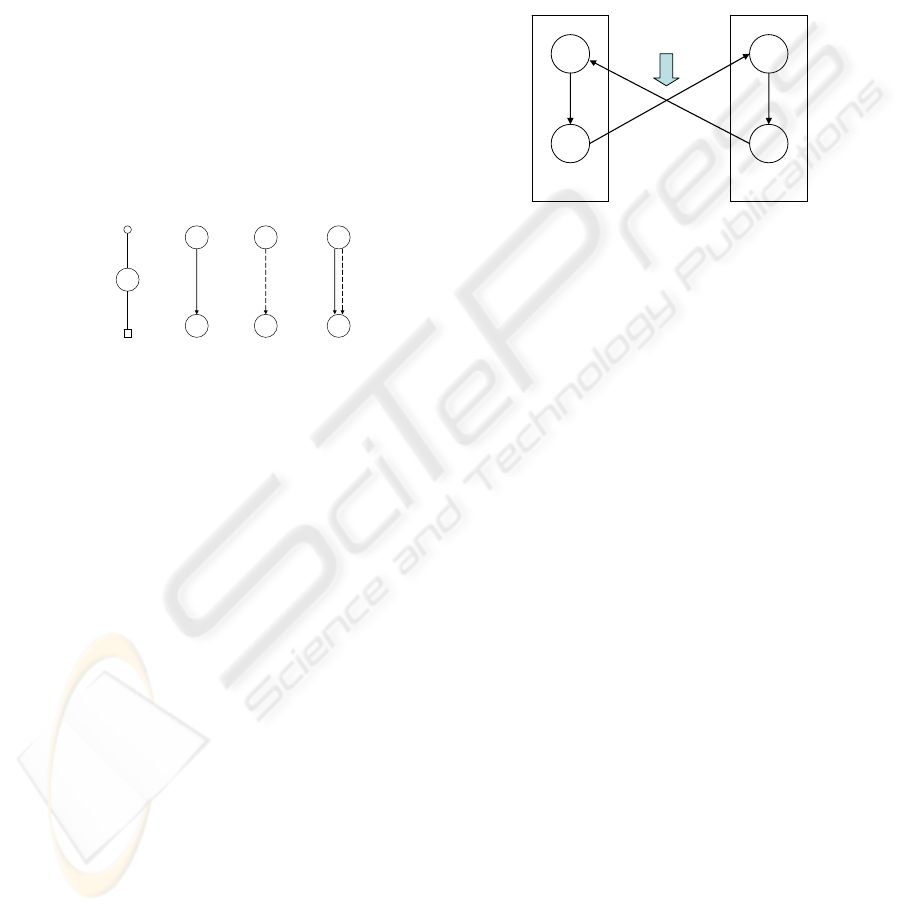

can also activate j. Figure 1 shows the legend of our

paper. In hybrid hierarchy, if an I-relation precedes

an A-relation in the hierarchy, then there is no

permission acquisition relation between the two end

roles. Consider s ≥

i

r ≥

a

j. Here, the user assigned to

s can neither activate j nor inherit the permissions of

j through the I-relation between s and r.

Lemma 1: Users assigned to r

1

can acquire

permissions of r

2

if and only if there exists at least

one hierarchical path from r

1

to r

2

such that no I-

relation precedes an A-relation in the path.

Figure 1: Legend of RBAC with Hybrid Hierarchy.

2.2 Secure Interoperation

Gong et al. (Gong, 1996) has proposed two

principles to the secure interoperation problem:

• Principle of Autonomy: If an access is

permitted within an individual system, it must

also be permitted under secure interoperation.

• Principle of Security: If an access is not

permitted within an individual system, it must

not be permitted under secure interoperation.

Typically, the principle of autonomy is ensured by

not changing the individual policy; and the principle

of security is ensured by detecting and removing the

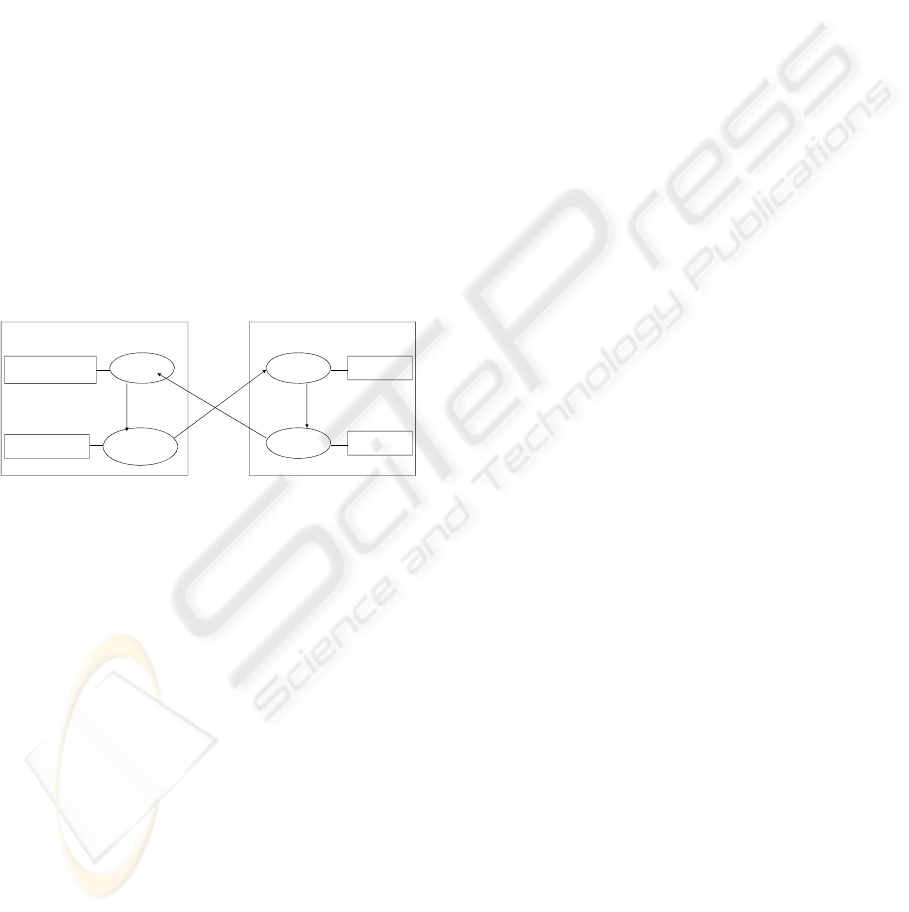

access cycles. As shown in Figure 2, assume some

interoperation requires r

2

of domain d

1

to be made

senior of r

3

of d

2

, and another interoperation requires

r

4

to be made senior of r

1

. There is an access cycle

(r

1

, r

2

, r

3

, r

4

, r

1

) and the principle of security has

been violated since the users of r

2

are now

authorized to acquire permissions of r

1

in d

1

. In the

literature, many global policy based approaches have

been proposed (Gong, 1996; Shafiq, 2005) to

address the secure interoperation problem in tightly-

coupled environment. A global policy is predefined

by central administrators by integrating all

individual access control policies. And the access

cycles are detected and removed in the global policy.

In a loosely-coupled environment, global policy

cannot be used since the interoperation needs are

dynamic. Several trust management approaches

(Blaze, 1996; Li, 2002) have been proposed to make

dynamic authorization decisions based on trust

policies. However, trust management can only solve

a part of the access control challenges in loosely-

coupled environment, as shown in Section 3.

Figure 2: Example of access cycles during interoperation.

3 LOOSELY-COUPLED

ENVIRONMENTS

3.1 Characteristic

The domains in a loosely-coupled environment are

typically independent to each other and are able to

carry out their major functions themselves. The

interoperation needs are raised dynamically to share

the data whenever needed. Therefore, the

interoperation needs in loosely-coupled

environments are dynamic and cannot be pre-

defined. For example, consider a distributed health

care system (e.g. HL7) that consists of different

hospitals, clinic, health care station, and other

related organizations. Assume Bob travels outside

his hometown and needs to go to an emergency unit.

The local hospital (Hospital A) might need to access

his health information from his home hospital

(Hospital B) to provide him with a proper treatment.

This particular interoperation need is driven by a

specific event (Bob needs to go to the emergency),

and we cannot predefine that Hospital A should

always be authorized to access Bob’s health

information from Hospital B.

3.2 Specific Access Control Challenges

The first challenge is how to locate the domains that

contain the requested permissions in the access

r

s

j

s

j

s

j

user

role

user-role assignment

permission

senior role

junior role

I-hierarchy IA-hierarchyA-hierarchy

role-permission assignment

r

1

r

2

r

3

r

4

Domain d

1

Domain d

2

Interoperation links

UNDERSTANDING ACCESS CONTROL CHALLENGES IN LOOSELY-COUPLED MULTIDOMAIN

ENVIRONMENTS

357

request. Once a particular interoperation need arises,

the requesting domain may not know which domains

contain the requested permissions, and a look-up

mechanism is necessary to locate those domains. For

example, the health care workers in Hospital A

needs to know which hospital or clinic has Bob

registered and contains Bob’s health information.

Although in this example Bob may carry his health

care card that contains the information of his home

hospital, in general we cannot assume that the

requesting domain always knows a priori the

domains containing the requested permissions. One

possible solution is to use a centralized database to

maintain such global information (e.g. the hospitals

a patient has registered in). However, such

centralized database could become very complex

and hard to manage. Moreover, it could also be the

bottleneck and suffer from single point of attack.

Therefore, decentralized look-up approaches are

more desirable in loosely-coupled environments. We

refer to this problem as Domain Discovery problem.

This challenge shows that Domain Discovery is

necessary in loosely-coupled environments.

Figure 3: Access cycles in a loosely-coupled environment.

The second challenge is how to make an access

control decision for a particular interoperation

request. Global policy based approach cannot be

applied here since the interoperation needs cannot be

predefined. For example, at the time when both

Hospital A and Hospital B join the network, the

administrators cannot pre-define that Hospital A can

access Bob’s health information from Hospital B.

This is because such interoperation need is only

necessary when Bob needs to go to the emergency

ward in Hospital A and this may never happen. In

the literature, trust management systems are

typically used to make authorizations among

unknown domains. In a trust management system,

each domain specifies its local trust policy (typically

consists of credentials that is required to access

some resources), and employs some credential

validation and trust negotiation approaches to make

the authorization decisions. For example, when the

healthcare workers in Hospital A request Bob’s

health information from Hospital B, Hospital B may

require that only the users with valid healthcare

licenses be allowed access to Bob’s health

information, and ask healthcare workers in Hospital

A to present their license in order to gain the access.

Once the license has been verified, the access

request is granted and the healthcare workers in

Hospital A can now access Bob’s health information

from Hospital B. This challenge shows that a Trust

Management component is necessary in loosely-

coupled environments.

The third challenge is how to prevent the access

cycle and preserve the principle of security during

the interoperation. The access cycles could be

formed when multiple authorized interoperations co-

exist within the same time period. Consider the

example shown in Figure 3. Assume Bob is

registered and taken cared of at his home hospital

(Hospital B), where both the doctor and resident are

authorized to access his healthcare information. Of

course, doctors have more privileges, such as adding

a new entry to his record, so Doctor role is made

senior to Resident role in Hospital B’s local policy.

In Hospital A located at another city, healthcare

workers are responsible for maintaining normal

health care information. There are specialist doctors

that are all experts of cancer and they may need

special privileges to maintain cancer-related

information. Therefore, SpecialistDoctor is made

senior to HealthCare-Worker in Hospital A. Now

assume that Bob needs to go to the emergency ward

in Hospital A when he travels to that city. To take

care of Bob, the healthcare worker in Hospital A

needs to access Bob’s health care records and also

needs to add a new entry to Bob’s records. So

HealthCareWorker of Hospital A is made senior to

Doctor of Hospital B to facilitate such

interoperation needs (Interoperation 1 in Figure 3).

Assume at the same time, hospital B receives a

cancer patient but is unable to make a proper

treatment plan since they are not experts of cancer.

The doctor in hospital B asks the resident to get

some help from the specialist doctors in Hospital A

(e.g. accessing some cancer-specific information in

Hospital A to learn how to make the proper

treatment). As a result, Resident of Hospital B is

made senior to SpecialistDoctor of Hospital A to

facilitate such interoperation needs (Interoperation 2

in Figure 3).

At this time instant when both

interoperations 1 and 2 in Figure 3 are authorized,

there exists an access cycle (shown by the four

arrows) and the principle of security is violated.

Unlike in a tightly-coupled environment, there

is no static global policy in loosely-coupled

Specialist Doctor

HealthCare Worker

Doctor

Resident

Hospital A Hospital B

Interoperation 1

Interoperation 2

adding entries …

access health

care records…

maintain normal health

care information…

maintain cancer-specific

information …

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

358

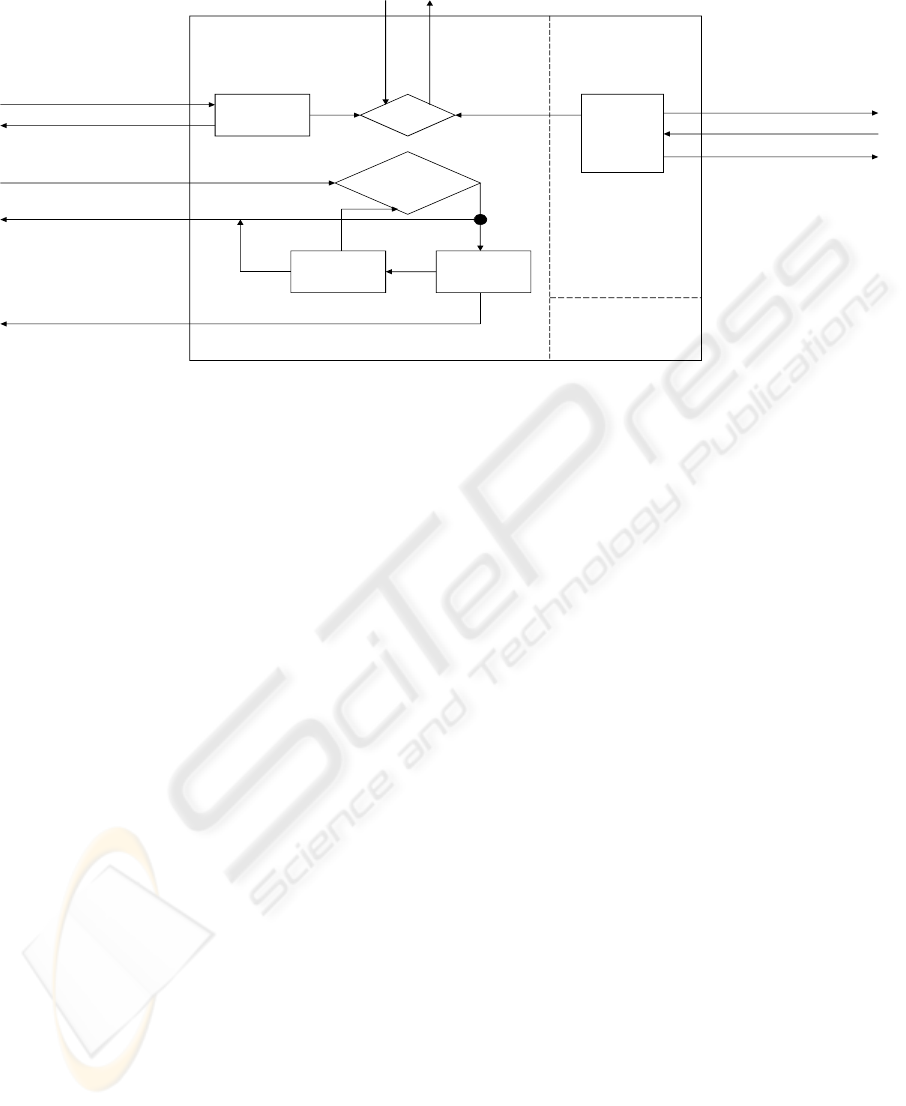

Figure 4: Architecture of our decentralized secure interoperation framework.

environments. Therefore, the existing access cycle

detection and removal approaches employed in

global policy based approaches in the literature

cannot be applied here. This challenge shows that

proper mechanisms to ensure principle of security

are necessary in loosely-coupled environments.

4 PROPOSED FRAMEWORK

Figure 4 shows the architecture of our decentralized

secure interoperation framework. The left part shows

the components involved when the domain is

providing resources to other domains’ access

requests, while the right part shows the components

when the domain is requesting resources from other

domains. An interoperation access request (iar) is

the access request such that the requesting domain is

different from the domain containing the requested

permissions, as defined formally below:

Definition 1 (Interoperation Access Request). An

interoperation access request, iar, is defined as a

tuple of <d

req

, P

dest

, r

req

>, where d

req

is the domain

issuing the request, P

dest

is the requested permission

set, and r

req

is the role in d

req

to access P

req

.

Note that users acquire permissions through roles in

RBAC. Therefore, besides the requested

permissions, the requesting domain should also

identify one of its local roles for its users to acquire

the requested permissions through. For example, an

iar= <Hospital A, {add an entry to Bob’s record,

read Bob’s record}, HealthCareWorker> specifies

that Hospital A requests to acquire the permissions

to edit and access Bob’s record through its

HealthCareWorker role. If authorized, all the users

of HealthCareWorker can acquire the requested

permissions.

4.1 Domain Discovery and Role

Mapping

Given an iar, we need to decide which domains

contain the requested permissions. First, the domains

receiving the requested permissions need to decide a

set of roles that contain a subset of the requested

permissions, and we refer to this as the Role

Mapping problem. Second, given the roles written

by the Role Mapping components of other domains,

the requesting domain needs to identify a set of

involved domains that together can provide exactly

the requested permissions.

In (Zhang, 2010), we have proposed a role-

mapping algorithm that can be used for the Role

Mapping component, and propose several domain

discovery protocols that can be used to identify the

involved domains. Based on the output of the Role

Mapping algorithm, we define the answer of iar as

below:

Definition 2 (Answer of iar). The answer of a given

iar=<d

req

, P

dest

, r

req

> by an individual domain d,

denoted by d.answer(iar), is the tuple of <d, P

contain

,

R

contain

>, where P

contain

⊆ iar.P

dest

is the subset of

requested permissions that is contained in d’s local

policy, and can be acquired through R

contain

, which is

a set of d’s local roles.

Role Mapping

interoperation access request: iar

answer to iar

Local Policy

local access

request: lar

answer

to lar

check

Domain

Discovery

check

interoperation access request: iar

answers to iar from other domains

interoperation session request: isr

Interoperation Policy

interoperation session request: isr

Trust NegotiationPolicy Integration

answer to isr: yes

no

update

check

check

yes

no

yes

answer to isr: no

Individual

Domain

modules when the domain

is requesting resources

modules when the domain is providing resources

UNDERSTANDING ACCESS CONTROL CHALLENGES IN LOOSELY-COUPLED MULTIDOMAIN

ENVIRONMENTS

359

Once the set of involved domains have been

identified by the Domain Discovery component, it

sends a session access request sar to each of the

involved domain, as below:

Definition 3 (Session Access Request). A session

access request, sar, is defined as <d

req

, r

req

, d

dest

,

R

dest

>, where d

req

and r

req

are the same as defined in

iar, d

dest

is the destination domain where sar is sent

to, and R

dest

= d

dest

.answer(iar).R

contain

is a set of

roles in d

dest

that the requesting domain wants to

assume.

Compared to iar, sar has a new field d

dest

since now

the requesting domain has identified a set of

involved domains and knows where to send its

request. Moreover, the requested permission set P

req

in iar is replaced by the requested role set R

dest

in

sar. Actually R

dest

is simply R

contain

specified in

d

dest

.answer (iar). For example, after Hospital B

returns the answer <Hospital B, {add an entry to

Bob’s record, read Bob’s record}, {Doctor}>,

Hospital A issues an sar = <Hospital A,

HealthCare-Worker, Hospital B, {Doctor}>

indicating that the users of HealthCareWorker in

Hospital A requests to acquire the permissions of

Doctor in Hospital B.

4.2 Trust Management

The Trust Management component is responsible for

deciding whether an sar should be authorized or not.

There are a lot of trust management approaches

proposed in the literature. Since our framework is

role-based, any role based trust management work

could be used here. For example, RT (Li, 2002) (a

role-based trust management language) can be used

in our framework to specify the relevant policies on

whether an sar should be authorized. In particular, if

users of HealthCareWorker in Hospital A can

prove Doctor in Hospital B according to the relevant

RT policies, sar = <Hospital A,

HealthCareWorker, Hospital B, {Doctor}> should

be authorized.

4.3 Policy Integration

Policy Integration component is responsible for

preventing access cycles and preserving principle of

security when facilitating an authorized sar. As

discussed before, the existing access cycle removal

approaches employed in global policy based

approaches cannot applied here. We propose a novel

policy integration approach that uses the special

semantics of hybrid hierarchy to prevent the access

cycles. For each authorized sar, we create an access

role for the requesting domain to access the

resources of the involved domain through hybrid

hierarchy, as defined below:

Definition 4 (Access Role). Given an authorized sar

= <d

1

, r

1

, d

2

, R

2

>, the access role of this sar, denoted

as ar (d

1

, r

1

)

,

is a newly created role in d

2

such that

∀r∈R

2

, we make r

1

≥

a

ar (d

1

, r

1

) ≥

i

r.

Figure 5a shows an example of the access role. We

can easily verify that the users of r

1

can acquire the

permissions of R

2

by activating ar (d

1

, r

1

), so the

interoperation has been facilitated. Consider the two

sars shown in Figure 5b. Although there is a cycle

(r

1

, r

2

, ar(d

1

, r

2

), r

3

, r

4

, ar(d

2

, r

4

), r

1

), there is no

violation of principle of security. This is beacuse in

d

1

the users of r

2

cannot acquire the permissions of

r

1

since there is an I-relation preceding an A-relation

in the path. This shows that as long as we use the

proposed policy integration approach by linking the

access role through hybrid hierarchy, the principle of

security will be implicitly preserved regardless of

the specific interoperation needs. We finally define

the interoperation policy and its checking rule:

Definition 5 (Interoperation Policy). Assume R and

AR represent the set of all roles and all access roles

in a domain d, the interoperation policy IP of d, is a

relation between AR and R: IP=AR×R

Definition 6 (Checking Rule of the Interoperation

Policy). A sar = (d

1

, r

1

, d

2

, R

2

) is said to be matched

in the interoperation policy if and only if: ∀r∈R

2

,

(ar(d

1

, r

1

), r)∈d

2

.IP

The interoperation policy is updated by the Policy

Integration component after the Trust Management

component has authorized an sar. Every time an sar

is received, we first check the interoperation policy

to see whether the sar has been authorized by the

trust management component. If not matched, we

run the Trust Management component to make the

authorization decision.

Figure 5: the use of access roles.

r

1

r

2

r

3

r

4

Domain d

1

Domain d

2

r

1

Domain d

1

r

3

r

4

r

5

ar(d

1

, r

1

)

Domain d

2

(a): sar=(d

1

, r

1

, d

2

, R

2

={r

3

, r

4

, r

5

}) (b): sar

1

=(d

1

, r

2

, d

2

, r

3

), sar

2

=(d

2

, r

4

, d

1

, r

1

)

ar(d

2

, r

4

) ar(d

1

, r

2

)

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

360

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we analyze the specific access control

challenges in loosely-coupled environments, and

propose a secure interoperation framework to

address these challenges. The proposed framework

consists of three components: Domain Discovery,

Trust Management, and Policy Integration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been supported by the US National

Science Foundation award IIS-0545912. We thank

the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

REFERENCES

Blaze, M., Feigenbaum, J., and Lacy, J. 1996.

Decentralized Trust Management. In Proceedings of

the 1996 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy

(May 06 - 08, 1996). SP. IEEE Computer Society,

Washington, DC, 164.

Ferraiolo, D. F., Sandhu, R., Gavrila, S., Kuhn, D. R., and

Chandramouli, R. 2001. Proposed NIST standard for

role-based access control. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur.

4, 3 (Aug. 2001), 224-274.

Gong, L. and Qian, X. 1996. Computational Issues in

Secure Interoperation. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 22, 1

(Jan. 1996), 43-52.

Joshi, J. B., Bertino, E., and Ghafoor, A. 2002. Temporal

hierarchies and inheritance semantics for GTRBAC. In

Proceedings of the Seventh ACM Symposium on

Access Control Models and Technologies (Monterey,

California, USA, June 03 - 04, 2002). SACMAT '02.

ACM, New York, NY, 74-83.

Li, N., Mitchell, J. C., and Winsborough, W. H. 2002.

Design of a Role-Based Trust-Management

Framework. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE

Symposium on Security and Privacy (May 12 - 15,

2002). SP. IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC,

114.

Shafiq, B., Joshi, J. B., Bertino, E., and Ghafoor, A. 2005.

Secure Interoperation in a Multidomain Environment

Employing RBAC Policies. IEEE Trans. on Knowl.

and Data Eng. 17, 11 (Nov. 2005), 1557-1577.

Zhang. Y., and Joshi. J. B. 2010. Role Based Domain

Discovery in Decentralized Secure Interoperations. To

Appear In Proceedings of the 2010 Collaborative

Technologies and Systems (May 17 – 21, 2010).

Chicago, IL.

UNDERSTANDING ACCESS CONTROL CHALLENGES IN LOOSELY-COUPLED MULTIDOMAIN

ENVIRONMENTS

361