A FRAMEWORK FOR DESIGNING SOCIAL

INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS

Di Loreto Ines

Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy

Gouaich Abdelkader

LIRMM, Université Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France

Keywords: Digital Natives, Social Web, Design Methods.

Abstract: Digital natives are the potential users of many applications designed and built today. For this generation

most of state of the art features related to social interactions and ubiquitous computing will be taken as

granted. For this reason, we have to provide design frameworks and methodologies that integrate these

features at early design stages. In this paper we propose a framework for designing Social Interactive

Systems (SIS) based on four criteria: identity, space, persistence and action. In order to demonstrate the

usefulness of the framework the paper will describe an experiment we held with a Social Virtual World

developed using the above-mentioned framework.

1 INTRODUCTION

Our era is characterized by the convergence of social

and ubiquitous computing. From one hand we have

the emergence of the social web paradigm (with

social sites such as Facebook and MySpace, and

social ’worlds’ such as Second Life). On the other

we have the massive use of ubiquitous interfaces

that allows computers to live out here in the world

with people. It is our opinion that the mix between

social and pervasive computing is an issue that

prompts us to rethink Interactive Systems Design. In

fact, the capacity to integrate social elements at early

design stages will make the difference between

successful or not applications. For this reason in this

paper we propose a framework based on four

elements: identity, space, persistence and actions

that are the means for building Social Interactive

Systems. In order to demonstrate the usefulness of

the framework the paper will describe an experiment

we held with a Social Virtual World developed

using the above-mentioned framework.

2 A FRAMEWORK FOR SOCIAL

INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS

DESIGN

This section of the paper presents the core elements

of the framework that can be used to design Social

Interactive Systems (SIS). The framework is based

on four elements: identity, space, persistence, and

actions. These elements are motivated by an

empirical analysis of current and past social software

and supported by major findings from psychology

and sociology. Actually, these elements represent

core features of any Social Interactive Systems (SIS)

targeted towards young generations (see Di Loreto,

2010). Hereafter, the semantics of each element of

the framework is described more in details.

Identity

Our point of view about Identity is the same as

social psychology’s approaches (Hogg, 1987), which

consider individual and social identity not as stable

characteristics, but rather as a dynamic phenomenon

(Harré et al., 1991). In these approaches, the choice

about what possible self to show is driven by

strategic moves (e.g., what features are more

relevant and effective for self-presentation) which

137

Loreto Ines D. and Abdelkader G. (2010).

A FRAMEWORK FOR DESIGNING SOCIAL INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS.

In Proceedings of the Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT, pages 137-144

DOI: 10.5220/0003034401370144

Copyright

c

SciTePress

participants can make within a particular situation.

In describing everyday interactions, Goffman

(Goffman, 1959) distinguished between two ways of

expressing information: information that is given

and information that is given off. Information that is

given is the conscious content of communication,

the voluntary symbolic actions that are mutually

understood. For example, a person who describes

their anger is giving information about their

emotional state. In talking about their anger

however, the person also gives off information,

through para-verbal characteristics such as tone,

volume, the choice of words, and non-verbal cues.

While information that is given is considered to be

within the actor’s control, information that is given

off is perceived by the audience to be

unintentionally communicated. A classical example

of ’identity announcement’ that has intentionally and

unintentionally elements is avatar personalization.

While we will not enter in detail here on its

implications the avatar is a visual claim for personal

expression that is constantly worked on. This

continuous work reinforces the concept of presence

and thus social presence. As another example of

collateral information, we can use the explicit

specification of a social network of acquaintance.

While it is true that social networks are built via a

series of invitations, usually members also have

some control over the visibility of their network for

others. This means that, for impression management,

a user will show only networks he/she wants to

show. For instance, some members can decide to

make their social networks visible only to their

direct acquaintances. In this case, there is a ’given’

information (the user chooses what to show about

his/her identity), but also a ’given off’ information

(derived e.g., from the kind of groups a user

showed/joined). From a design point of view, we

can say that allowing both the kinds of identity

representation becomes the starting point for a social

evolving identity.

Space

If we look carefully, the language we use to describe

our experience of the virtual environment is a

reflection of an underlying conceptual metaphor:

’Cyberspace as Place’ (Lakoff et al., 1988). This

means that we are transferring certain spatial

characteristics from our real world experience over

the virtual environment. The metaphor ’Cyberspace

as Place’ leads to a series of other metaphorical

inferences: cyberspace is like the physical world, it

can be ’zoned’, trespassed upon, interfered with, and

divided up into a series of small landholdings that

are just like real world property holdings.

In this little presentation the term space was

joined with the term place. In reality, for the good

functioning of a SIS it is important to distinguish

between the two terms. Actually, the literature about

space and place is fairly massive and diverse. A

converging definition of the difference between

space and place does not exist, however in his book

about urban spaces and places, Carmona (Carmona

et al., 2002) distinguishes among dimensions of an

urban space. While space is divisible, place is not.

Place is complex, inextricably multi-dimensional,

lived, experienced, meaningful (with of course multi

- meanings).

This means that while space is a well-defined

topographical entity, place is the result of human

inhabitation, (social) interaction, and the like. We

are located in spaces, but we act and develop

individual and social experiences in places. We

claim that in order to design a social application, it is

essential to allow by design the creation of public (at

different levels) places for aggregation but also the

creation of private places (Wenger et al., 2002).

Besides, the lever of personalization can be used in

order to allow the shift from spaces to places. Only

taking possession of the space, and manipulating it

to turn it in something we like, we can transform it

in a place.

Persistence

As we have seen, in order to create a social identity

in an online environment several elements are

required. An additional element is persistence (of

personal identity in the system). In a non-persistent

world, it is not possible to have a history of actions

and thus allow, for example, the creation of a

reputation like in real life. Moreover, Danet (Danet

et al., 1997) argued that synchronicity is associated

with ’flow experiences’, a state of total absorption,

and a lack of awareness of time passing. This idea of

synchronicity is linked to the idea of temporality, a

linear procession of past, present, future. This

particular nuance (synchronicity as process) is very

interesting if we think that interaction with media

and media perception is changed. In fact, advances

in technology and the speed of network connections

are blurring distinctions between synchronous and

asynchronous communications (Joison, 2003).

Synchronous and asynchronous communications are

thus processes that happen during time. The idea of

communication as a process is very consistent with

the idea of persistence and is another element

supporting social awareness.

Actions

In this part, we discuss physical and psychological

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

138

mechanisms that regulate human actions in order to

understand why the action element has to be

considered as a pillar in the design of social

software. The first theory we want to describe is the

so-called ‘thinking through doing’. This theory

describes how thought (mind) and action (body) are

deeply integrated and how they co-produce learning

and reasoning (Klemmer et al., 2006). Jean Piaget

(Piaget, 1952) postulated that cognitive structuring

requires both physical and mental activity. In a very

basic sense, humans learn about the world and its

properties by interacting within it. As a second

support, we can cite embodied cognition. Theories

and research of embodied cognition regard bodily

activity as being essential to understanding human

cognition (Pecher et al., 2005). While these theories

address cognition through action in physical

environments, they also have important implications

for designing interactive systems. In fact, body

engagement with virtual environments constitutes an

important aspect of cognitive work. For example,

one might expect that the predominant task in Tetris

is piece movement with the pragmatic effect of

aligning the piece with the optimal available space.

However, contrary to intuitions, the proportion of

shape rotations later undone by backtracking

increases (not decreases) with increasing Tetris-

playing skill level. In fact, players manipulate pieces

to understand how different options would work

(Maglio et al., 1996).

To summarize, because an action is always an

action-over- something, the kind of interaction

spaces and objects we create in a Social System will

influence which cognitive work the user will do over

the system.

2.1 The Overall Framework

While we presented the four elements in a separate

way, their usefulness in the construction and

evaluation of social environments is mostly linked to

the interaction between these elements.

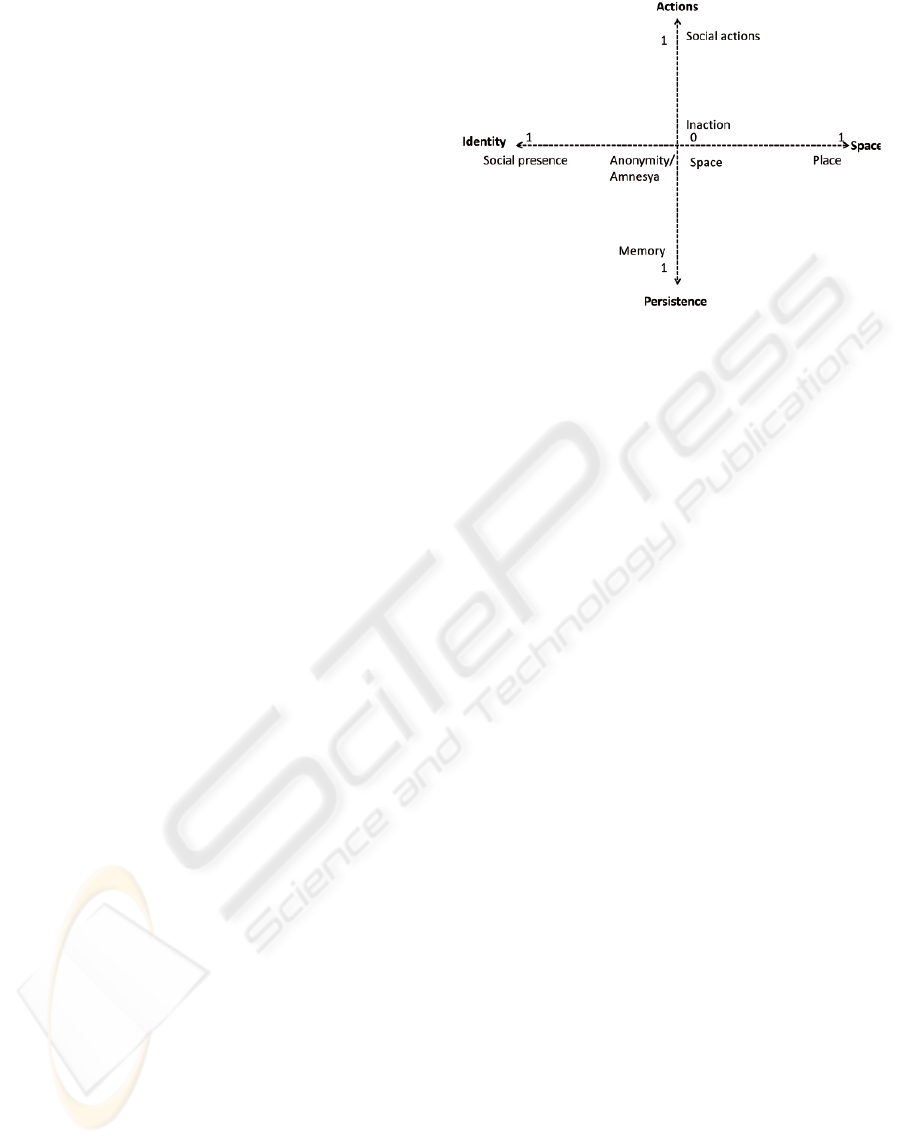

In a way each element can be thought of as a line

(an axis) that starts from the absence of the element

to the fulfillment of its presence for a Social

Interactive System. For example, for the concept of

identity its total absence is anonymity while its

fulfillment is social presence (with intermediate

points such as personal identity construction).

For the concept of space its total absence is

topographical space while its fulfillment is social

places (with intermediate points such as third places

and personal places). For the concept of persistence

its total absence is system 'amnesia' while its

Figure 1: The graphical representation of the 4 elements

as axis

fulfillment is memory (with intermediate points

linked more or less to the concept of persistence).

Finally, for the concept of action its total absence is

the obstruction of action (i.e., my user can only look

at my application) while its fulfillment is social

actions (with intermediate points such as public

personal actions and the like). Figure1 shows the

above-described axis graphically. This way to

represent the four elements has an additional value.

In fact a designer can create an ‘Expected Profile’

for an application using the four axis. For example,

if he/she decides that his/her to be developed

application has to have a high level of self-

presentation elements (an avatar, a profile, and so

on) he/she will give a high value for the identity

axis. Same thing happens for the persistence axis.

For example, a social network based on micro

actions such as Facebook, does not require the same

level of persistence as a virtual world such as

Second Life. In the first case the persistence axis

will have a medium value, in the second a high

value. And so on.

Note that the total framework is not simply a list

of elements (i.e., its application does not mean to put

one after the other the four elements in your system)

but it is created through the delicate balancing

between them. Actually, it is up to the designer to

choose which element of the framework to stress or

not during the creation of a dynamic experience such

as in a social application. In addition, only once the

‘Expected Profile’ of the application is decided, the

designer chooses which features add to the system.

This means that what is important is the balancing

between the elements not which features the

designer puts in his/her system.

A FRAMEWORK FOR DESIGNING SOCIAL INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS

139

3 THE SCHOOL SOCIETY

WORLD

As mentioned in the introduction of this paper social

elements really influence the use of an application in

our era. In order to support the above-mentioned

assertion we will describe a Serious Virtual World

we developed using the framework: School Society.

From a practical point of view, the environment

used in this experiment was able to support our

students both in online learning, and in recreational

experience. Note that due to the subject of this paper

we will not analyze the virtual world as a learning

environment, but as a social environment. Apart

from studying, there is no final aim in School

Society. Each Resident can find his own way to

inhabit this word.

The Gameplay for the School Society World

When the user enters the world for the first time, an

animated intro scene describes how the world was

created. Sometime in the future mankind has

managed to practically destroy the world via

magnetic weapons. The world was knocked off its

axis and continents have sunk into the ocean. Only

small islets remain. Several decades later, the

survivors have managed to remodel their lives. They

have built homes on the islets, as well as shops and a

school. The top, elite students of this school are

recognized worldwide as the best people in the

world: the Legendary Eagles.

4 THE FRAMEWORK IN

ACTION

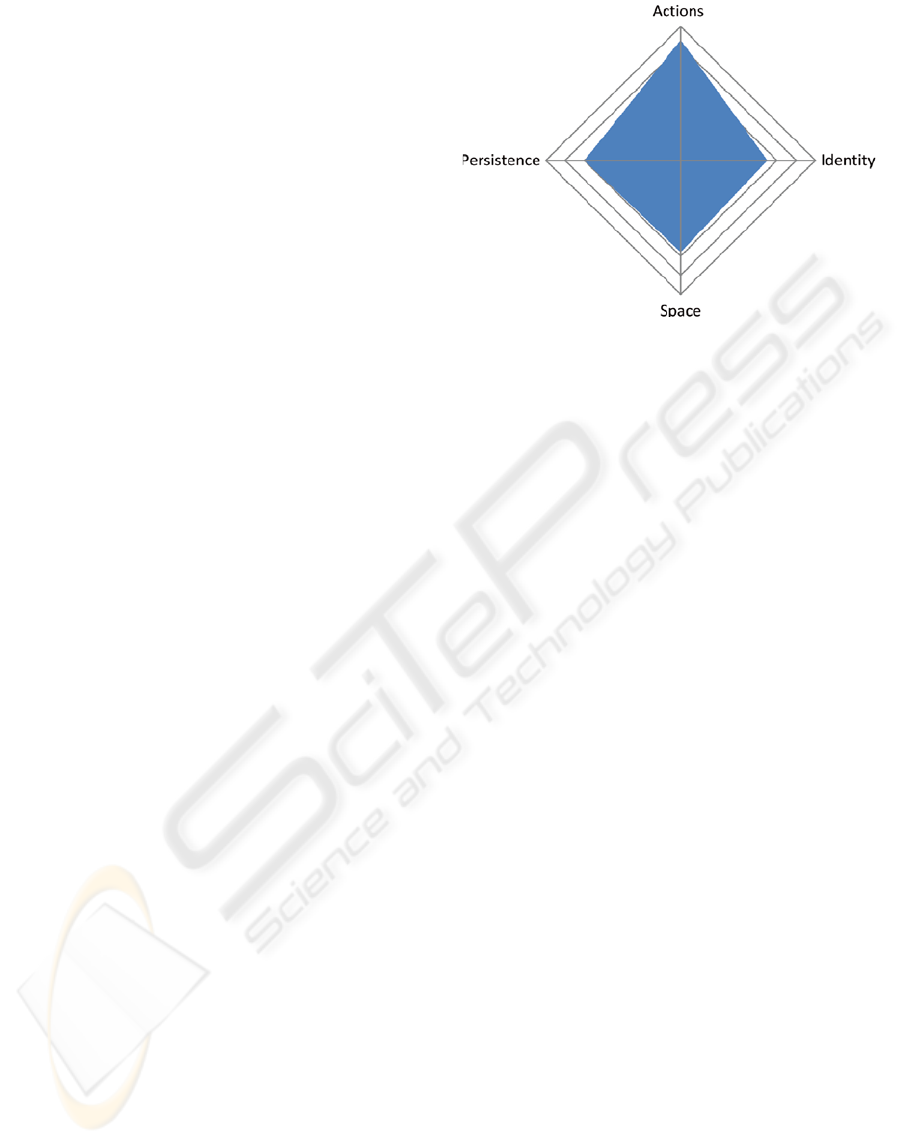

The first step in this experiment was to determine an

'Expected Profile' for the to be developed

application. In this case the choice was a balanced

'Expected Profile' (see Figure 2. In order to

understand how the profile was evaluated see Di

Loreto, 2010). This means that the virtual world has

to enable deep personalization, in both the space and

the identity aspects. The world has to be a persistent

one and it has to enable the creation of a community

memory.

Hereafter the most interesting elements (both

from the framework application and from gameplay

point of view) are described in more detail.

Space in Action

First of all, as an element of identification, the

Resident's home is indicated as 'My home'. In

addition, when the Resident reaches a public place,

Figure 2: The Expected profile for the School Society

virtual world.

an NPC (Non Playing Character) welcomes him

(with 'special attention' if he is the winner of some

world competition - an element also linked to

identity construction).

At this moment the public buildings in the world

are: the Pub, the Market, and the School.

The basic idea was to use the Pub as a potential

'third place' for the world. In fact the Pub is a place

where the Resident can 'informally' meet people he

does not know. On the contrary, the Market is only a

space to buy items for competitions. The school is

the more 'formal' space. In this ‘space‘ there is a

different section for each different quiz the students

can take.

A Particular Space: The Gazette

School Society's world has its own newspaper called

the 'Gazette'. The 'Gazette' is the 'voice' of the world.

Every interesting event that has occurred in the

world can be found in it. This journal is a kind of

herald that publicizes 'public' activities (in-world

events such as tournaments) but also 'private'

activities (what your friends have done). The result

is a dynamic public and private space that changes

over time and is the 'memory' of the interactions

within the world.

Identity in Action

Each student can personalize the avatar he chose

when he entered the world whenever he wants.

Each avatar possesses the following attributes:

Name: When the student enters the world for the

first time he is asked to choose a name for his avatar.

Body Attributes: When the student enters the

world for the first time, he is asked to construct his

avatar that will represent him during the interactions.

However, he can change his appearance whenever

he wants during the inhabitation of the world.

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

140

Finally, a student can use the gold he has earned

through quizzes to buy objects in the market that he

can use to add personal items on his avatar.

Activity in Action

As said the Pub is a particular space. In fact, in the

pub the student can chat with people who are in it

even if they are not on his buddy list (i.e., if they are

not his friends).

In the School building students can take part in a

set of social actions (apart from taking the quizzes

the professors have created). In particular they can

take part in two interesting social activities:

participate in tournaments and challenge the

professor.

For the first activity the student is alone against

others students. If he can beat all the other

participants his success is published on the world

journal, the 'Gazette'. In this case the social aspect is

driven through competition.

The other activity is literally a social one. If a

professor is available, students can organize

themselves in groups and challenge the teacher.

Practically, while the students will take quizzes

created by the teacher, the teacher will answer to a

quiz created by the students. For each answer the

team gives, the time available to the teacher to solve

the quiz increases or decreases (based on wrong or

right answers). If the team is able to leave the

teacher no time to solve the quiz, it will be the

winner of the contest, rewarded with the Medal of

Honor 'Where eagles dare'. In this case their bravery

will also be publicized in the 'Gazette' (and so will

be publicly visible).

Time in Action

First of all the game's world is a persistent one. This

means that each time the player disconnects his

account, the game will save his status: his

modifications, his avatar's appearance, his

experience, and so on. In addition, all old 'copies' of

the Gazette are available for consultation. In this

way all public events, all competition winners, and

the like are stored creating a memory for the

community.

5 EVALUATING THE

FRAMEWORK THROUGH USE

In order to demonstrate the assertion stated at the

beginning of this paper (i.e., that the presence of

social aspect modulated through the framework

influences the use of an application) the developed

School Society virtual world was given to a group of

students to use. Hereafter more details on the

experiment.

5.1 The General Method of the

Experiment

Three (3) groups of students were asked to

consistently use the system for about one week.

Each group had different 'views' over the systems

(i.e., the group could access a different set of

features). The different views were created in order

to block some aspect of the framework (e.g., identity

representation) and then evaluate if this absence

impacted on the user's experience in the way

supposed while describing the framework.

Subjects

The participants in the experiments were 38 students

of the University Institute of Technology (I.U.T.) of

Montpellier. The gender distribution of participants

was 34 (90%) male and 4 (10%) female, with an

average age of 20.

Students were divided into three groups:

Group 1: Full vision over the system

Group 2: Vision of the system without Identity

features

Group 3: Vision of the system without social

features

Note that this means that all the groups were

using the same system. They just had different views

of it. This kind of division was done in order to

demonstrate the effective importance of social

features and of the identity factor.

The number of participants in each group (about

13 people) was coherent with the findings that 'with

high complexity, a study with more than 15 cases or

so can become unwieldy' (Miles el al., 1994, p.30).

5.2 Procedure and Materials

At the beginning of class, subjects in all groups were

introduced to the virtual world of School Society.

The students were asked to use the systems for 7

days.

The interactions were 'free' for the students. They

just had to inhabit the world as they liked. The idea

was that if the students did not feel the absence of a

feature they would not ever look for it (i.e., if they

did not feel the necessity to use a chat, they would

never open a chat).

Materials

At the end of the week students were asked to

A FRAMEWORK FOR DESIGNING SOCIAL INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS

141

evaluate their experience in School Society. Data on

the experiment were collected through two channels.

In fact, the survey method was coupled with tracking

methods based on technological features (log files,

number of sessions, sessions' length, and the like).

The general idea was that by cross-referencing

users' feedback and number of interactions

(qualitative and quantitative data) it would be

possible to understand if the designed social system

really works or not from the social point of view.

Survey and Qualitative Measurements

The survey was conceptually divided into three

parts. Several questions directly addressed students'

satisfaction with the social aspects (quality of the

interaction). Another group of questions addressed

graphic appeal and usage problem issues. A final

group of questions provided an overall measure of

satisfaction with the entire system (the overall

reaction to the system). The different parts of the

survey were designed in order to understand if the

global satisfaction with the system was influenced

by graphic appeal and usage issues, which are not

directly linked to social satisfaction. The main idea

was to distinguish between attitudes to the system

itself and attitudes to using the system in a social

way. Questions with Lykert type scales were

avoided where possible in order to avoid different

subjective approaches to these kinds of questions. In

general, a scale of 0-4 was adopted in the process.

Log Files and Quantitative Measurements

In order to measure sociability from a quantitative

point of view the system logged all the actions made

by the students. In particular Preece's suggestions

(see Preece, 2001) on determining sociability in

online communities were taken into account.

Preece says that determinants of sociability

include measures such as the number of participants

in a community, the number of messages per unit of

time, member satisfaction, and some less obvious

measures such as amount of reciprocity, the number

of on-topic messages, trustworthiness and the like

(Preece, 2001). While in this case the number of

participants in the community had no significance

(the participants were only the students) a list of the

other elements taken into account is described in

detail hereafter.

5.3 Use of Sociability Determinants for

the Evaluation

1-Number of Messages, Messages per Member

indicate how engaged people are within the

community. Number of private messages (i.e., in

other friends' mailbox) and number of public

messages (in the Pub) were regrouped under the

label 'Number of messages' and measured during the

experiment.

2-The Amount of on-Topic Discussion was

evaluated only in public discussions and only to

understand the relationship between learning topics

and strictly social topics (i.e., the topic of the post as

not evaluated by its profundity or its real impact on

'community life').

3-Reciprocity is concerned with giving to a

community as well as taking from it. While this

element is normally measured through the number of

answered posts, in this case the measure of

reciprocity was also determined through the

challenge feature (number of reciprocated

challenges).

4-Flaming and Uncivil Behavior, such as abusive

language or harassment. In this experience this

measurement was not relevant for two main reasons:

the presence of teachers who acted as moderators,

and the fact that the experience lasted only one

week.

5.4 Results and Discussion

Before beginning analysis it is important to address

a possible limitation of this study. Students of an

I.U.T may not necessarily be the 'average user'. This

could influence how fast they learn to use the system

or its perceived usability, but not the sociability they

put into it. In fact, because of their age they can be

considered an 'average' Digital Native. In the case of

this experiment the measurements were linked to the

sociability of the system and not to its

usability/ability to learn to use it. For this reason we

believe that the composition of the sample did not

influence the experiment.

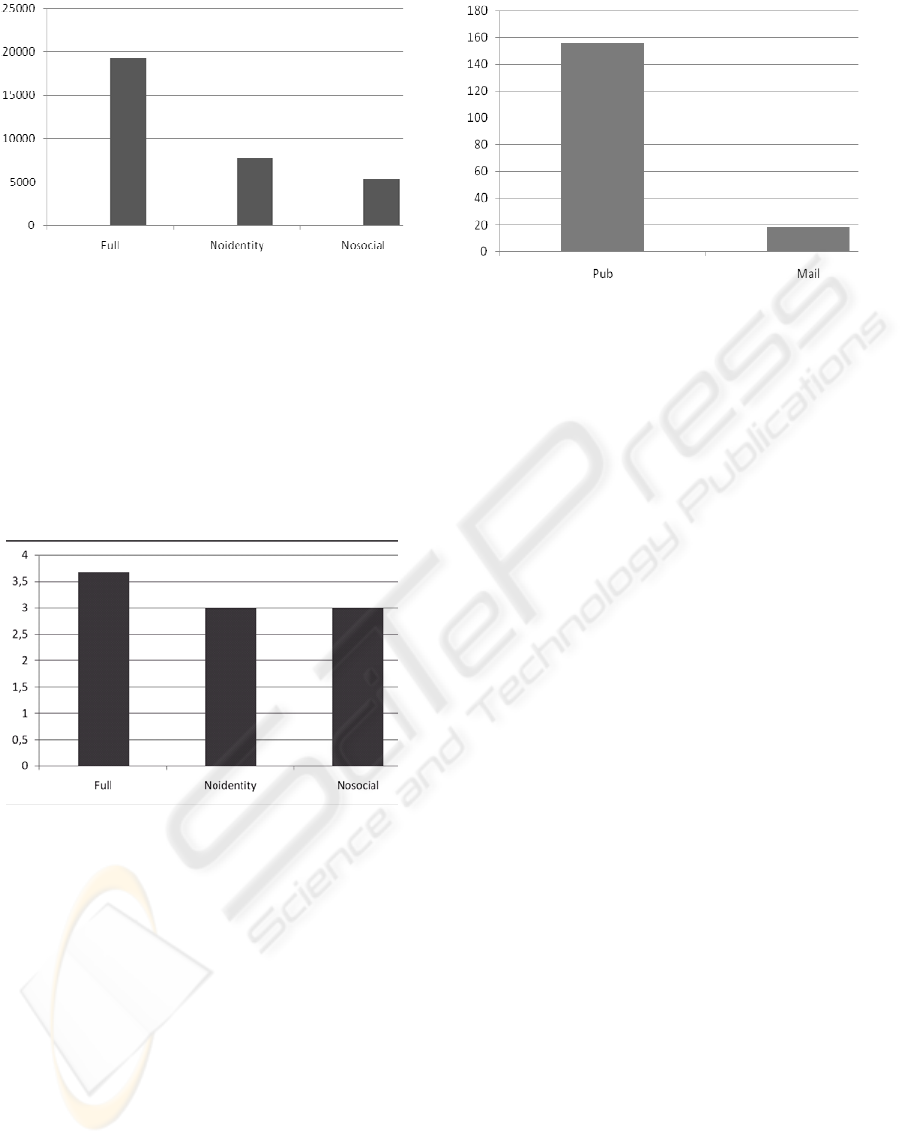

System Usage

Figure 3 shows the general system usage (the

number represented in the y-axis is the number of

total general actions that impacted over the system,

including posting, taking quizzes etc.) for each of

the groups. As we can see the group with full

features used the application noticeably more than

the other two groups. In addition, the group with no

identity features used the system more than the one

with no social aspects but noticeably less than the

one with full features.

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

142

Figure 3: School Society: general system usage.

Global Satisfaction and Generic Issues

Parameters linked to system issues or graphic appeal

(derived from the survey) are very similar for all the

groups. On the contrary the global satisfaction of the

system experience shows a difference for group one

(Full features- see Figure 4). Interesting enough, the

group that was not able to use identity elements

rated it in a similar way as the group without social

elements.

Figure 4: School Society global satisfaction.

Sociability Determinants

Figure 5 shows the trends for exchanged messages.

Public messages have greatest numbers than the

private ones (we will return on this topic later in the

paper). This is coherent with the perceived

usefulness (derived from the survey) of the two

features: while chats rated an average of 3.8, mail

rated 2.8 (scale 0-4). It is interesting to note that

while Gazette was used more for lurking activities

its perceived usefulness is 3.6.

This is not a surprising finding. Lurking and

contemplating activities are one of the most common

actions in social environments (Wenger, 1999).

Perceived Sociality of the System

The perception of the sociality of the system was

obtained through the survey. To the question ‘In

Figure 5: School Society: trends for exchanged messages.

general, about the fact that someone was playing the

same game as you’ 90% of participants answered

they were encouraged to use the application and the

main motivation (derived from another question)

was because they play to beat their friends. Only

four people answered that the presence/absence of

others did not influence their use of the application.

Nobody answered that the presence of others was an

obstacle to the use of the application.

To the question ‘Do you think that leaving

messages for your friends in game is’ 45% of

participants answered they find it useful because

they like to comment on what their friends do, 3

people answered they find it useless, and the

majority (50%) answered they preferred the public

chat (the Pub). This is more coherent with Digital

Natives' use of social tools than with the use they did

of the two media in the application.

In fact, the Pub had a flow of message very

Twitter like (that in our opinion contributed on its

success), while the note on mail was given based on

the standard use of private messages and not on the

ingame use of mail.

In addition, in the Pub participants with no

identity features quickly added a nickname to each

post. The result was something like: “Guest says:

Guillaume: who is in the Guest group?”.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

POSSIBLE IMPROVEMENTS

This paper started asserting that the mix between

social and pervasive computing is an issue that

prompts us to rethink Interactive Systems Design. In

fact, the capacity to integrate social elements at early

design stages will make the difference between

successful or not applications.

Ending our discussion we can say that the

A FRAMEWORK FOR DESIGNING SOCIAL INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS

143

experiment described in this paper supported this

assertion. Firstly, the absence of social features

deeply influenced the use of the application (as the

different usage of School Society demonstrated, see

Fig 3).

In addition, the experiment demonstrated that

also the identity aspect is very important in a Social

Interactive Systems. In fact, not only it influence

system usage, it generates a sort of ‘need for

identity’ in the social context (as the Pub example

demonstrated).

However, while trends are visible even in this

short (in terms of time) experiment, we are aware

that more interesting information could be obtained

extending the time of the experiment. For this reason

we are working on another experiment (on the same

system) for a longer amount of time (the idea is to

let the world 'live' for at least two months).

Another interesting experiment could be done

‘playing’ with the Action element. In fact, additional

interesting information could be obtained doing a

similar experiment that will use Identity, Space, and

Time as reference points, and will play with

different levels of social actions in order to answer

questions such as: More or less to what degree do

visible social actions affect social interactions? In

addition, we want to demonstrate the importance of

the space and the time aspect in the same way as we

did for the identity aspect.

Finally, the idea of adapting complex software

systems by creating different profiles based on the

four dimensions of the framework in order to answer

other questions could also be explored. For example,

for a large democratic debate application is the right

thing to do give all age ranges the same vision as the

'first vision' (i.e., the view they have over the system

the first time they enter it)? Would a simplified

vision in all aspects be better for older people or

would they not need, for example, the space aspect

for a good performance? And so on.

REFERENCES

Carmona, M., Heath, T., Oc, T. and Tiesdell, S., 2002.

Public places-urban spaces: the dimensions of urban

design. Architectural Press.

Danet, B., Ruedenberg-Wright, L., and Rosenbaum-

Tamari, Y., 1997. Hmmm... where’s that smoke

coming from? writing, play and performance on

internet relay chat. Journal of Computer- Mediated

Communication, volume 2.

Di Loreto, I., Gouaich, A., 2010. An Early Evaluation

Method For Social Presence In Serious Games. In:

Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on

Computer Supported Education CSEDU 2010. 2nd

International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU-10), 4/2010.

Goffman, E., 1959. The presentation of self in everyday

life. Doubleday.

Harré, R. and Langenhove, L. V., 1991. Varieties of

positioning. Journal for the Theory of Social

Behaviour, 21, 4, 393–407.

Hogg, M., 1987. Social identity and group cohesiveness,

in J. Turner, M. Hogg, P. Oakes., S. Reicher, & M.

Wetherell (eds.), Rediscovering the social group: A

self-categorization theory. Oxford: Blackwell, 89-116.

Joinson, A. N., 2003. Understanding the Psychology of

Internet Behaviour: Virtual Worlds, Real Lives.

Palgrave Macmillan.

Klemmer, S. R. and Hartmann, B., 2006. How bodies

matter: Five themes for interaction design. In

Proceedings of Design of Interactive Systems 74,

140–149.

Lakoff, G. and Turner, M., 1988. Categories and

Analogies 3. University Of Chicago Press.

Maglio, P., & Kirsh, D., 1996. Epistemic action increases

with skill. In LEA (ed.), Proceedings of cognitive

science society.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A., 1994. Qualitative data

analysis : An expanded sourcebook (2. ed.). Thousand

Oaks: Sage.

Pecher, D. and Zwaan, R. A., 2005. Grounding Cognition:

The Role of Perception and Action in Memory,

Language, and Thinking. Cambridge University Press.

Piaget, J., 1952. The origins of intelligence in children.

International University Press.

Preece, J., 2001. Sociability and usability in online

communities: determining and measuring success.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 20 (5), 347-

356.

Wenger, E., 1999. Communities of practice: Learning,

meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., Mcdermott, R., and Snyder, W. M., 2002.

Cultivating Communities of Practice. Harvard

Business School Press, Boston.

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

144