REQUIREMENTS AND MODELLING OF A WORKSPACE FOR

TACIT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN RAILWAY PRODUCT

DEVELOPMENT

Diana Penciuc, Marie-Hélène Abel

Alstom Transport, 93400 Saint Ouen, France

diana.penciuc@transport.alstom.com

Heudiasyc CNRS UMR 6599, University of Technology of Compiègne, BP 20529 , 60 205 Compiègne, France

Didier Van Den Abeele

Alstom Transport, 93400 Saint Ouen, France

Keywords: Tacit Knowledge, Knowledge Management, Organisational Learning, Organisational Memory, Railway

Products Development, Product-line Development.

Abstract: Our work is focused on finding ways to foster tacit knowledge in the context of a company providing

railway transport solutions. Our study refers to a specific process of railway product development, context

in which, we consider the problem of tacit knowledge as a concern of organisational learning. We present

our findings on the requirements and modelling of a workspace supporting tasks of the process considered

and sustaining both organisational learning and tacit knowledge management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modern large-scale companies are more and more

dynamic and rise to the increasing customer

demands by continually coming up with innovatory

products. It becomes important to minimize the

production cost of new products by shortening the

product life cycle. One method of achieving this is

reusability of not only the existing formalized

knowledge (e.g. architectures), but also the

knowledge that employees gained after years of

experience.

This paper focuses on finding ways to discover,

store and reuse this knowledge, referred to as tacit

knowledge.

Product-line engineering is a method of creating

products in such a way that it is possible to reuse

product components and apply planned variability to

generate new products. This yields to a set of

different products sharing common features (Birk

2003). These common features are summed up in a

core or a “reference platform” and used to engineer

each of the products in the product-line. A few

examples of commonalities (core assets) are:

architecture, software components, documents etc.

The advantage of the product-line engineering lies in

the reusability of this “reference platform”, which

leads to significant gains, such as engineering work

reduction, time-to-market and costs reduction, or

improved quality.

This paper addresses the case of an international

company providing railway transport systems.

Railway market is characterised by a great diversity

and dynamics of demands guided by the customer’s

background (e.g. habits, historical reasons), evolving

technologies, competitors etc. In the context of this

heterogeneity, having a “reference platform” brings

considerable improvements, but it cannot perfectly

match each request. Thus, the problem of adapting it

appears.

When responding to a customer’s demand the

core has to be properly adapted in order to map the

specific needs of a customer. Adapting the reference

platform relies not only on its explicit definition or

adaptation rules, but also on the tacit knowledge

(Polanyi 1966) of the employees, on non-formalized

practices and exchanges between employees etc. As

this knowledge is volatile, it can be easily forgotten,

61

Penciuc D., Abel M. and Van Den Abeele D..

REQUIREMENTS AND MODELLING OF A WORKSPACE FOR TACIT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN RAILWAY PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT.

DOI: 10.5220/0003100000610070

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2010), pages 61-70

ISBN: 978-989-8425-30-0

Copyright

c

2010 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

put aside or ignored; contrary to explicit knowledge

it cannot be stored and reused, and therefore cannot

constitute a lasting capital for the firm (Boughzala

and Ermine 2006). Past decisions, lessons learnt,

customer specificities and solutions to specific

problems are a few examples of knowledge that may

be lost. Consequences of this fact are: spending time

to reinvent past or existing solutions, repeating

mistakes from the past. Once codified, this

knowledge could be a source for improving existing

practices, avoid re-iteration and reinforce the “re-

use” strategy.

Our goal is to find a solution for managing tacit

knowledge involved in the process of adapting the

“reference platform”. A set of 40 employees was

interviewed, and data gathered from their answers.

Data revealed the need for tacit knowledge

management. An analysis of this need led to a set of

requirements for a future knowledge management

platform and the proposal of first solutions.

The paper is organized as follows. First, we

provide the context of our work. Next, we present

the analysis of needs we carried out through

interviews and emphasize the need of a workspace

dedicated to managing tacit knowledge and

supporting organisational learning. Then we discuss

background information on Enterprise 2.0

technologies and the MEMORAe approach to

organisational learning, in order to justify our

choices. In the final part we present the requirements

and first modelling of the proposed workspace. We

conclude with future directions.

2 CONTEXT

It is a fact that one of the most critical processes of

product development is “Tendering”. This process is

triggered as a consequence of a request for proposal

(RFP) announcement and its purpose is to build a

formal offer that will be submitted to the customer.

It is an early stage of product development with a

significant influence on contract establishment and

success of the final product. Furthermore, decisions

taken here often cannot be changed and time

allocated to this process can be very short (up to six

month).

For these reasons, our research is focused on

analysing the “Tendering” process and providing

knowledge management solutions adapted to this

process needs.

2.1 The “Tendering” Process

The study was carried out in the company A. Its

mission is to provide solutions for railway transport

management.

In the following, the stakeholders and the

workflow of the Tendering process are described.

Stakeholders are the customer and the “ad-hoc

teams” of companies competing to obtain the

contract. In general, in a railway context, the term

“customer” may stand for:

• The demander (a society demanding a railway

product, local authorities),

• The consultant (the demander can employ a

consultant to write its demand),

• The operators of the railway system,

• The final users (voyagers).

Through this paper, the term “customer” will be

used to refer to parties involved in specifying the

request for proposal (RFP), which encompass the

first three above mentioned categories. “Ad-hoc

teams” are built according to the specificity of each

offer. Functions of the members are related to:

technical, commercial, planning, and support to the

Tendering process.

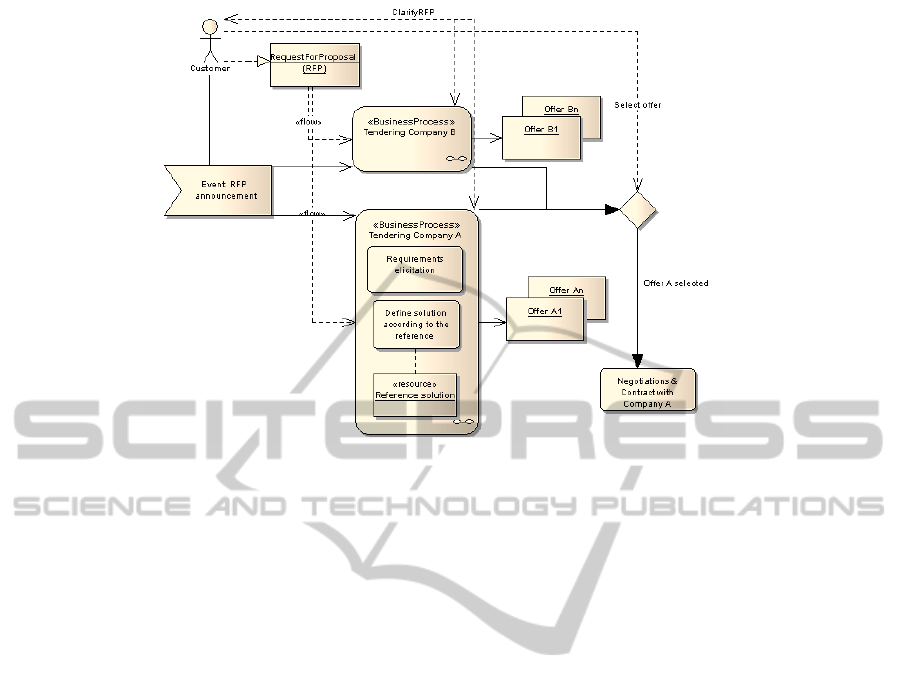

Figure 1 presents a simplified workflow of the

“Tendering” process within the studied Company A,

competing with the Company B to obtain the

contract of a customer.

In the company A, comparing the demand with

the reference solution leads to the building of a

customer solution reflected in the offer.

Understanding of the RFP and customer’s need is an

iterative activity which results in several successive

proposals coming from the two companies (OfferA1,

OfferB1;…;OfferAn, OfferBn).

The customer then chooses the company

proposing the most convenient offer and the

Tendering process ends with negotiations and

contract with the chosen company.

Given the complexity of this process and the

diversity of specific knowledge coming from the

various disciplines, we have decided to limit our

study to the technical aspects of the “Tendering

process”. These are presented in more details in the

following section.

2.2 Technical Analysis

The purpose of the technical analysis is to

understand the technical requirements of the

customer and to propose an appropriate

solution/system to answer the demand.

The entry of this activity is the technical part

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

62

Figure 1: Tendering process in Company A competing with Company B.

of the RFP and knowledge acquired during a

previously-made rough analysis of the RFP. The

RFP consists of any type of resources used by the

customer to specify his need. Typical resources are

one or more paper or digital documents containing

text and graphics or images, but they can be videos

as well.

The result of the activity is a “Technical

Answer” of the offered system comprising mainly

the architecture of the system, the specification of

the requirements as understood by the team, the

compliance with the demand and the cost of the

solution.

Technical requirements analysis is accomplished

by collaboration between multiple stakeholders. The

actor managing this activity is the Tender Technical

Manager who will select a number of collaborators

according to the needs of a specific offer. The so-

formed team will comprise key actors of the

development of a system: suppliers, subcontractors,

system engineers, etc.

Activities to accomplish are:

• Clarify requirements in the RFP.

•

Identify gaps between the requirements and the

reference solution and determine which of the

gaps can be resolved.

• Determine how reference solution can be

adapted.

• Define the design of the system.

• Identify work breakdown structure.

• Decide on the cost of the solution.

Requirements are allocated to each team member

according to their mission and results are shared

with the Technical Manager. Division of work and

collaboration are important as the knowledge of the

participants is complementary and sharing their

knowledge helps the team to converge faster to an

adequate solution.

Choice of the proposed solution is based not only on

the knowledge of the reference solution, but also on

the experience and know-how of each member of

this team. Experience and know-how are often lost

as they are not capitalized and therefore represent a

loss for the company’s individual and collective

memory. Loss appears in several situations: a) an

expert leaves the company and knowledge is lost

forever or b) knowledge is stored in the inactive part

of the memory and therefore is not actively used.

This latter is due to the unshared knowledge

(individual written/unwritten knowledge), to

difficulties to locate existing knowledge, or to

ignorance. On the contrary, once capitalized,

knowledge would serve as a means to speed-up the

Tendering process, to improve practices for future

offers, to trigger new knowledge and to support

apprenticeship. Benefits are two-folded: boost

individual knowledge as well as collective

knowledge resulted not only from the sum of

individual knowledge, but also from the added-value

of the collaboration between individuals.

To accomplish this, members should be helped not

only on their individual tasks but also on the

collaborative ones. In order to understand how this

could be accomplished, a set of needs were

REQUIREMENTS AND MODELLING OF A WORKSPACE FOR TACIT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN

RAILWAY PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

63

identified through a better understanding of the

tendering process and particularly of the Technical

analysis.

These needs were further used to determine how

knowledge management could respond to the

problems previously mentioned.

3 ANALYSIS OF NEEDS

As stated before, success of a customer solution is

due to: a good adaptation of the reference solution

and learning and understanding customer’s need.

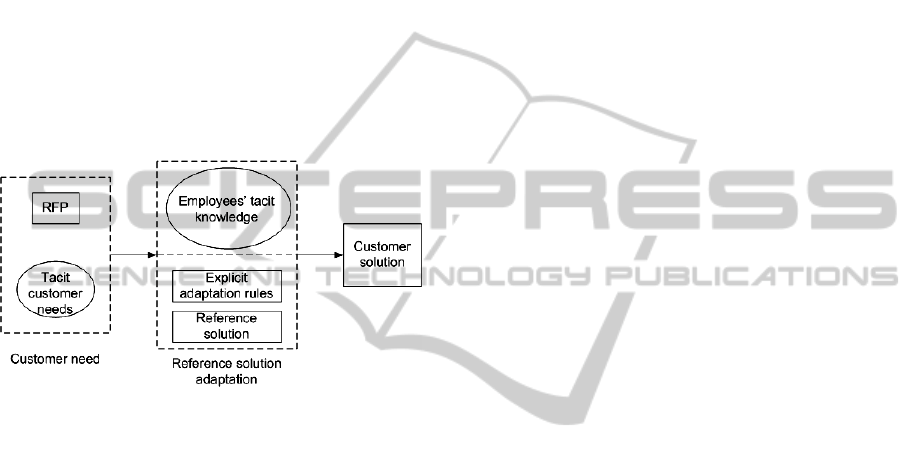

Figure 2 details the contribution of these elements

by highlighting the explicit (represented by squares)

and the tacit ones (represented by ellipses).

Figure 2: Role of explicit and tacit knowledge in finding a

good customer solution.

The adaptation of the reference solution is based not

only on explicit rules but also on tacit rules dictated

by employees’ tacit knowledge. Knowing

customer’s need implies understanding the need

expressed explicitly in the RFP but also the un-

written, un-said need which may be learnt by asking

questions, observation etc.

To summarize, three factors are determinant for the

success of a customer solution: 1) the employees, 2)

the reference solution and its adaptation to a demand

and 3) the knowledge about a customer.

In order to better understand how these three

factors impact the “Tendering” process and the

technical analysis, a study of the internal

environment has been undertaken using interviews.

Details about interviews data and results are exposed

in the next paragraphs.

3.1 Interviews Data

From the sample of 80 employees selected, 40 of

them agreed to collaborate. Employees have been

selected from different divisions and with different

functions, which allowed to have a diversity of

opinions and a much deeper understanding of the

business. Divisions considered were Tender group

and its links to other divisions contributing to carry

out activities during tender: finances, platform group

etc. The subjects were selected based on the

suggestions coming from the management and from

the already interviewed employees.

Therefore, we selected a set of 15 questions

directed to find out more about:

1. Employee’s professional profile and daily work.

2. The reference platform and its adaptation to a

customer request.

3. Knowledge about the customer and its demand.

The first category grouped topics related to the

employee’s mission and tasks, tools and resources

used to accomplish his job, knowledge critical for

his job, relations to other people.

The second category listed questions correlated

to the elements of a reference solution, problems of

adapting it to a customer demand, ways of

improving the reference solution and its adaptation,

and performance indicators of the reference solution

and adaptation process.

Questions in the third category were directed

towards finding the characteristics of a request for

proposal, revealing problems related to the

understanding of the RFP, and determining the

elements impacting the adaptation of the reference

solution to the request stated in the RFP.

3.2 Interviews Results

The results of our interviews are two-folded:

• A number of activities impacted by prevalent

tacit knowledge use were identified.

• Specific needs were identified.

In what the first matter concerns, the selection

criteria consisted in the degree of human

contribution in accomplishing the activities. By way

of illustration, we cite: “capture customer needs”,

“estimate risks”, “identify gaps between the

reference solution and the demand of the customer”.

As regard to the technical analysis, Table 1

summarizes the results of the interviews and

underlines several issues which need to be

improved.

The study revealed that a heterogeneity of

tools/methods are used to accomplish technical

analysis, which does not allow a rigorous

capitalization of knowledge. Informal knowledge

coming from individual work and informal exchange

(e.g. meetings) may be lost, as they are not

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

64

Table 1: Interviews results and issues that need to be improved.

Category Overall results/observations Identified needs

Employee’s

professional profile

and daily work

Observations may be captured on personal paper

notebook or computers

Customer and technical team of the company do not

necessarily use the same vocabulary

Customer and technical team do not have the same

vision on the system

Synchronizing work between the members of the

team is difficult

Communication is accomplished mainly through

emails, meetings or telephone

Good anticipation is crucial as time is short

Need for a common vocabulary

Need for a tool to improve

communication and capitalisation of

key knowledge (past experience, etc.)

Need to better and faster locate

previous experience

The reference

platform and its

adaptation to a

customer request

Choices made when adapting the reference solution

not always formally justified

Better understanding of the customer could reduce

gaps and risks

Not easy to anticipate the impact of modifications to

be made to the reference solution in order to adapt it

to a demand; but, lessons-learnt could ease decision-

making

Decide the balance to keep between reference

maintenance and customer satisfaction is difficult

Need to capitalise choices made,

decisions

Need to better understand customers in

order to prepare a more easy-adaptable

reference solution

Need to better handle the complexity of

the reference solution

Customer

experience

Return on experience not systematically captured

and shared during the process or from one offer to

another

RFP may evolve in time; RFP traceability not well

performed

Customer’s context and use of the system should be

well captured

Need to better capitalise the history of a

client

Need to capture more knowledge

elements not written in the RFP or

elsewhere

systematically registered.

Observations showed that a common workspace

supporting individual and collective work during the

technical analysis is needed, although it does not

exist today. This will sustain formal and informal

exchange of knowledge.

Existing technologies were studied in order to

establish the basis for the future workspace.

4 RELATED WORK

The preliminary study of the Technical analysis

revealed the importance of a workspace enabling

knowledge capitalization, sharing and new

knowledge creation.

Moreover, it clearly showed the importance of

tacit knowledge and collaboration in accomplishing

tasks during Technical analysis.

The way collaborators are chosen, decisions are

taken, priorities are identified, anticipation is

accomplished, are all issues of tacit knowledge.

(Nonaka and Tackeutchi, 1995) consider that

through socialization, the barriers of tacit knowledge

can be overcome and knowledge transmitted to

others and thus become a collective good.

For all these reasons we can affirm that we are

facing a problem of organisational learning and

therefore we are seeking for appropriate means to

challenge it. Indeed, according to (Zhang 2003), an

organisational learning process is 3-folded and

concerns three processes: individual learning, social

learning (allowing collaboration between

individuals) and knowledge management.

Considering this, we chose to examine Enterprise

2.0 technologies and MEMORAe (Abel 2009a), an

approach to support organisational learning.

4.1 MEMORAe

The aim of MEMORAe is to construct operational

links between e-learning and knowledge

management in order to build a collaborative

learning environment. In order to do so, this

approach associates: knowledge engineering and

educational engineering; Semantic Web and Web

2.0 technologies (Leblanc, 2009). The underlying

REQUIREMENTS AND MODELLING OF A WORKSPACE FOR TACIT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN

RAILWAY PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

65

concept for the knowledge management is the

organisational memory, which Dieng (Dieng, 1998)

defines as an: “explicit, disembodied, persistent

representation of knowledge and information in an

organization, in order to facilitate its access and

reuse by members of the organization, for their

tasks”. By adapting this concept to the learning

process, the concept of Learning Organisational

Memory was proposed and its implementation uses

ontologies that index learning resources. Social

processes in exchange, are facilitated by Web 2.0

technologies.

The advantage of the MEMORAe approach over

using Enterprise 2.0 technologies is the integration

of the workbench, learning and socialization support

into the same platform. From the knowledge

management perspective, this allows to accomplish a

directed knowledge management in such a way that

knowledge creation and sharing are guided by the

learning process, which avoids knowledge

overabundance and favours innovation (Abel,

2009b).

4.2 Enterprise 2.0

Enterprise 2.0 is a term first used by McAffee in

2006 (McAffee, 2006) to name digital “platforms

that companies can buy or build in order to make

visible the practices and outputs of their knowledge

workers”. These platforms are the equivalent for

enterprise intranet of the popular “Web 2.0”

technologies on the Internet, bringing to the light the

benefits of socialization and collaboration.

We considered for our study the following

technologies enabling knowledge capture,

organising, storing and sharing: RSS feed, wiki,

blog, microblog, forum, social networks,

folksonomies. RSS feed can be used for real-time

capture of knowledge from the sources one is

interested with. This technology is not Web2.0

specific but it could be suitable when combined with

collaborative tools, given the short time available for

the team to accomplish its mission.

Microblogs would be appropriate to

communicate short pieces of news and guide users

to other sources more complex of information (in the

way Twitter does it). A comparison of 19 enterprise

microshraing tools is given in (Fitton, 2008).

Blogs could be employed by each team member

to write their own reflexions and notes regarding

assumptions made or notes about requirements etc.

Forum could be employed to allow exchange of

questions/answers in order to clarify requirements

not well understood.

A social network could keep in contact the members

of the team with collaborators sharing the same

interests (maybe a collaborator closer to the

customer, or subcontractors) or help them detect

experts. Generally, we can affirm that a social

network can relate between them different

communities of practice (Garrot-Lavoué, 2009).

A wiki could be provided to increasingly “build”

knowledge on a specific customer. A study

presented by (Stocker, 2009) showed that, in order

to provide concrete results, corporate wikis have to

solve a clearly specified problem crucial for the

business and the work practices of employees.

An analysis of commercial and open source

Enterprise 2.0 tools according to the services they

provide is presented in (Büchner, 2009).

We have shown how Enterprise 2.0 technologies

may contribute to the socialization and collaboration

processes. Nevertheless, these technologies should

be combined in order to provide efficient support.

Moreover, a simple combination of tools is not

enough and therefore, further knowledge

management support has to be added to them in

order to increase their capability.

5 WORKSPACE MODELLING

Based on the previous observations, it was decided

that a workspace was needed to support

organisational learning in the way MEMORAe

approach does it.

In order to model this workspace we have first

identified a set of requirements based on use cases.

We extracted our use cases from a selection of

typical working situations revealed during the

interviews. The use cases are exposed in the next

section.

5.1 Workspace use Cases

We consider the case of a RFP containing text

documents and we take as example the following

statement contained in the RFP: “The system shall

provide an emergency power production system

synchronous with the public supply”.

Typically, a reader reinterprets this statement

according to his experience: “Power supply should

be continuous even in the case of an incident”.

Case 1: The reader may choose to make an

annotation to the initial statement in order to

remember easily its meaning.

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

66

The expression “emergency power production

system” is not usual, but due to his experience he

understands that the customer is talking about a

source of energy which may be a battery or an

electric generator.

Case 2: There is no other sentence in the RFP that

can clarify customer need. The reader decides,

taking into account the context of the demand what

to offer to the customer.

Case 3: There is no other sentence in the RFP that

can clarify customer need. The reader decides he has

not sufficient information to take a decision. He

may: a) consult his collaborators or b) propose to

send the question to the customer or c) consult

resources he may consider relevant (e.g. previous

demands of the same costumer).

Case 4: When customer consulted, the following

situations may appear: a) requirement is

reformulated, as to be clear for all the parties; b) a

new requirement will be added, to specify missing

points.

Case 5: The reader finds another statement

specifying that “The emergency power production

system should be able to function at least 2 days”.

The reader infers that the customer needs an electric

generator, given that a battery could not provide

alimentation for such a long period.

Case 6: It was decided the customer needs an

electric generator, but the reference solution does

not support this component, so the requirement is

considered a gap. Two cases are possible: a) if the

gap can be solved, statement is marked compliant; b)

if the gap cannot be solved, statement is marked

non-compliant.

5.2 Workspace Requirements

When analysing the use cases, we can observe that,

generally, there are two types of actions one can

make:

• Individual actions (personal reflexion, decision,

individual tasks, like in Case 1, Case 2, Case 3

c), Case 5, Case 6).

• Collaborative actions (like in Case 3 a) and b),

Case 4 ).

Therefore, we decided that the workspace will have

two main components: a workbench and a

communication space.

The workbench will be dedicated to individual

learning while the communication space will be

dedicated to the collaborative learning. In addition, a

knowledge management component will support the

capitalization of knowledge emerging from the two

spaces and will allow users to query and search for

existing knowledge.

Requirements were then identified based on the

use cases and grouped in: requirements for the

workbench and requirements for the communication

space.

5.2.1 Requirements for the Workbench

The workbench should satisfy at least the

requirements:

• The workbench shall contain all necessary

resources for one to do his job. Resources consist

of RFP resources and personal resources which

one may need in order to accomplish his tasks

(like stated in Case 2 c)).

• The system shall provide to the user a means to

visualise the requirements to be analysed or any

other resource related to a customer or his

requirements.

• User shall be able to edit his notes (as free-text

annotations) while reading a statement contained

in the RFP.

• The system should allow new requirements

registration for the case new needs, which are

not already specified, are identified (like in Case

3 b).

• The system should allow multiple annotations on

a requirement.

• Each user will decide on the visibility of each of

his annotations to other stakeholders.

5.2.2 Requirements for the Communication

Space

The communication space should satisfy at least the

requirements:

• The communication space shall allow user to

collaborate with other stakeholders and to

obtain/transmit real-time knowledge about a

topic he is interested in, or a news.

• System shall allow authorised users to create ad-

hoc communities (e.g. tender technical manager

should be allowed to create a tender technical

team).

• The system should allow easy communication

between the team members on an annotation of a

requirement (Case 2, a),b).

• The system should provide a way for a user to

find and stay in contact with any other

person/community that could help him in his

work (e.g. with a community dedicated to the

customer owner of the current RFP).

• A user will be informed each time news appear

(e.g. new instructions are given from the

management) or a task was allocated to him.

REQUIREMENTS AND MODELLING OF A WORKSPACE FOR TACIT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN

RAILWAY PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

67

• System should allow a user to locate knowledge

about a topic.

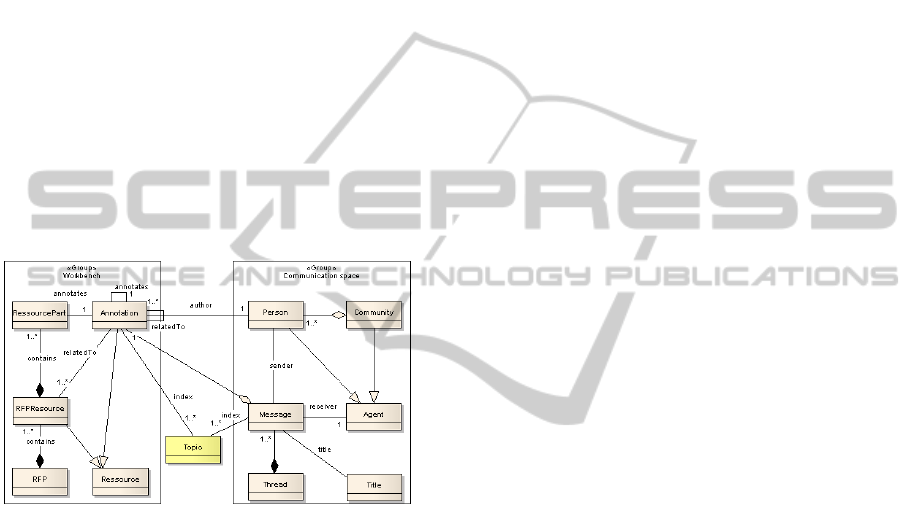

5.3 Workspace Model

Once requirements defined, we proceeded to the

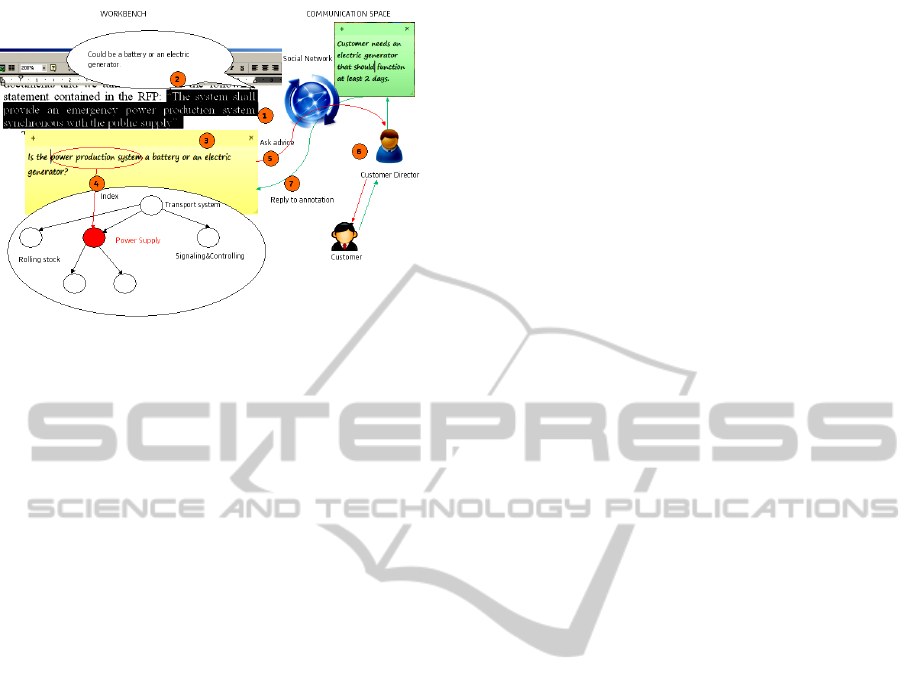

modelling of the workspace. A simplified model is

presented in Figure 3, which highlights workbench

and communication space elements as well as the

way the two are intertwined through one ore more

topics. One or more topics will be chosen by a user

to index an annotation made on a part of a resource.

Users will contribute with their knowledge

externalised through annotations, messages

exchanged or other resources and stored in a

knowledge base. Once stored, users will have the

possibility to look-up for knowledge by locating it

through a direct search or by locating a potential

owner of this knowledge via the communication

space.

Figure 3: Workspace model.

The workbench main elements are the RFP

resources and the annotations one can make on

existing resources. An annotation may annotate a

part of a resource (e.g. a text representing a

requirement) or another annotation (e.g. an

annotation which is the response to another

annotation edited by a stakeholder). Annotations

may be related one to another in two cases: 1) they

correspond to the same topic or 2) the user decides

to make a direct link between them via the

“relatedTo” relation. This latter can also be used to

relate the annotation to a resource (e.g. the user

decides to attach a drawing to complete the

annotation).

The author of an annotation is a Person (e.g. a

member of the technical team) which may choose to

send it as part of a message to an Agent (e.g. a

colleague or to the whole community: the technical

team).

The communication space is represented by

persons/communities and the threads tracking

messages exchanged between users. A Message

contains an annotation and corresponds to one or

more topics.

We note that topics allow not only to index

annotations but also messages exchanged in the

network, allowing therefore to capture and store

informal content and link it to formal content which

is RFP content. Topics will be defined by the

domain ontology: the “Transport system” ontology.

As stated in (Uschold, 1996), the role of the

ontology is to:

• Assist communication between people and

organizations.

• Achieve interoperability between systems.

• Improve system engineering.

The ontology will provide the common vocabulary,

allowing understanding between not only the

members of the technical team, but also between the

technical team and the customer. Furthermore, once

created, its consistency can be checked (when

represented in an appropriate formalism) and reused.

Topics, along with the information about the

members of the technical community and the

information specific for a Tender (e.g. about the

customer, the strategy, etc.) will provide a context to

any knowledge captured during the Technical

analysis. Contextual information can then be used to

locate and retrieve needed knowledge.

Corresponding to the use case Case 3 b)

presented in the 5.1 section, Figure 4 shows how the

workspace will be used according to this scenario.

Step 1: The reader selects a text to work with;

Step 2: He reinterprets the statement;

Step 3: He makes an annotation to the statement,

he writes a question;

Step 4: He chooses from the ontology one topic

(Power Supply) to index his annotation.

Step 5: He sends a message containing the

annotation through the social network to the

Customer Director, knowing that this latter can

directly address his question to the customer.

Step 6: The Customer Director clarifies the

question;

Step 7: The Customer Director will then respond

to his question by sending him another message

which will be also indexed with the same topic.

Suppose that Luc, the Technical Leader, wants

afterwards to check all the elements in all current

RFP resources and in all past tenders corresponding

to the same customer and concerning the “power

system” or related to it. When launching his search,

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

68

Figure 4: Workspace demo for Case 3 b).

all the elements indexed with the “Power supply”

topic will be retrieved, as well as the elements

indexed with topics having a relation to the “Power

supply” topic.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we have shown the contribution of tacit

knowledge in accomplishing tasks during railway

product development. In the context of a specific

activity like the “technical analysis” we detailed the

problems generated by the loss of tacit knowledge

which can arise when knowledge is not capitalized,

an employee leaves the company or he changes his

function. We think the loss of knowledge can be

overcome through a workspace favouring

organisational learning. We concluded that this

workspace has to sustain three processes: an

individual learning process, a social process for

collaborative learning and a knowledge management

process. Based on the analysis of needs, we deduced

that these processes will be supported by: 1) the

workbench helping employees to accomplish their

analysis 2) the communication component allowing

socialization and collaboration, 3) the knowledge

management component unifying the previous two

and allowing to capitalize knowledge by classifying

it into topics. According to the use cases revealed

during the interviews we defined a set of

requirements which were further used to realize a

first modelling of the workspace. As this model is

not complete, our next goal is the refinement of the

model.

Our future work will equally consist in the

implementation of this model. In the section “related

work” we presented some of the possibilities of

putting into practice our proposal, but these

tools/technologies cannot fully respond to the

requirements of our workspace (especially regarding

the annotation of resources, which should be

supported by the workbench). It is for this reason

that we are looking forward for means to develop

our proposal.

REFERENCES

Abel, M.-H., Leblanc, A., (2009a). Knowledge Sharing

via the E-MEMORAe2.0 Platform. In Proceedings

of 6th International Conference on Intellectual

Capital, Knowledge Management & Organisational

Learning, Montreal Canada, pp. 10-19, ACI, 10.

Abel, M.-H., Leblanc, A., (2009b). A web plaform for

innovation process facilitation. In IC3K 2009

International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management, Madeira Portugal, pp. 141-146, ACM,

10.

Birk A., Heller G., John I., Schmid K., Maßen von der T.,

Müller K., (2003). Product Line Engineering: The

State of the Practice. In IEEE Software, pp. 52-60,

November/December.

Boughzala I. And Ermine J.-L (2006). Trends in

Enterprise Knowledge Management. USA: ISTE.

Büchner, T., Matthes, F., Neubert, C., (2009). A Concept

and Service Based Analysis of Commercial and Open

Source Enterprise 2.0 Tools. In: Proceedings of the 1th

International Conference on Knowledge Management

and Information Sharing, Madeira, Portugal, pp. 37-

45.

Dieng R., Corby O., Giboin A., Ribière M. (1998).

Methods and Tools for Corporate Knowledge

Management. In Proceedings of the Eleventh

Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition, Modeling and

Management (KAW’98), Banff, Alberta, Canada, 17-

23.

Garrot-Lavoué E., (2009). Interconnection of

Communities of Practice: A Web Platform for

Knowledge Management.

In International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing (KMIS 2009),

Madeira, Portugal, 6-8 October 2009, p. 13-20.

Leblanc, A., Abel, M. (2009). Linking Semantic Web and

Web 2.0 for Learning Resources Management. In

Proceedings of the 2nd World Summit on the

Knowledge Society: Visioning and Engineering the

Knowledge Society. A Web Science Perspective,

Chania, Crete, Greece, September 16 - 18.

McAfee, Andrew P., (2006). "Enterprise 2.0: The Dawn of

Emergent Collaboration", In Sloan Management

Review 47 (3): 21–28.

Nonaka I., Takeuchi H. , (1995). The knowledge-creating

company : How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press,

New York.

REQUIREMENTS AND MODELLING OF A WORKSPACE FOR TACIT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN

RAILWAY PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

69

Polanyi M., (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Routledge.

Stocker A., Tochtermann K., (2009). Exploring the value

of enterprise wikis – A Multiple-Case Study. In IC3K

2009 International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management, Madeira Portugal, pp. 5-12, ACM, 10.

Uschold M., Gruninger M., (1996). Ontologies: principles,

methods and applications. In Knowledge Engineering

Review 11 (2), June.

Zhang, R., and Zhang, Y., (2003). Systems requirements

for organizational learning. In Communications of the

ACM, vol. 46, no 12, pp. 73-78.

DAML Ontology Library, Annotation.

http://www.w3.org/2000/10/annotation-ns#

Fitton L. (2008). Enterprise Microsharing Tools

Comparison. Retrieved Mai 19, 2010, from

http://pistachioconsulting.com/wpcontent/uploads/200

8/11/enterprise-microsharing-tools-comparison-

110320081.pdf

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

70