NOMIS: A Human Centred

Modelling Approach of Information Systems

José Cordeiro

1

, Joaquim Filipe

1

and Kecheng Liu

2

1

EST Setúbal/IPS, Rua do Vale de Chaves, Estefanilha, 2910-761 Setúbal, Portugal

2

The University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, RG6 6AF, U.K.

j.cordeiro@computer.org, joaquim.filipe@estsetubal.ips.pt

k.liu@reading.ac.uk

Abstract. Current approaches to information systems (IS) still ignore its human

nature resulting too often in technical IS project failures. One of the reasons

seems to be their scientific and technical bias following a philosophical

objectivist stance. One way to overcome this narrow view is to use a paradigm

that takes properly into account the human element, his behaviour and his

distinct characteristics within organisational and business domains. This is the

purpose of Human Relativism (HR) a new philosophical stance centred in the

human element and focused in the externalisation of his behaviour namely

human actions. In order to introduce, describe and propose a suitable approach

to IS development following HR principles this paper introduces NOMIS, a

normative modelling approach for IS. NOMIS integrates the key notions and

views of three IS socio-technical approaches, namely Organisational Semiotics,

the Theory of Organised Activity and Enterprise Ontology in a coherent and

consistent human-centred modelling approach. The new vision provided by

NOMIS is intended to furnish a more realistic, comprehensive, and concise

modelling of IS reality. In this paper some examples of this vision expressed by

NOMIS views and some of its specific representation diagrams will be shown

applied to an empirical case study of a library system.

Keywords. Information systems, Information systems development approaches,

Information Systems modelling, Human-centred information systems, Human

relativism, Organisational semiotics, Theory of organized activity, Enterprise

ontology, NOMIS.

1 Introduction

Current approaches to information systems (IS) still ignore its human nature resulting

too often in technical IS projects failure. One of the reasons seems to be their

scientific and technical bias following a philosophical objectivist stance. To overcome

the problems felt by these hard approaches a group of soft approaches have been

proposed. These soft approaches usually follow a social constructivist philosophical

stance that sees the world as socially constructed by individuals and groups where the

social and human aspects take the leading role. Although promising to solve the

issues of hard approaches, soft approaches did not succeeded as it can be deduced by

its low adoption rate. Therefore, we think that a possible solution will be to have good

Cordeiro J., Filipe J. and Liu K.

NOMIS: A Human Centred Modelling Approach of Information Systems.

DOI: 10.5220/0004465200170035

In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Enterprise Systems and Technology (I-WEST 2010), pages 17-35

ISBN: 978-989-8425-44-7

Copyright

c

2010 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

and accurate theoretical principles, a modelling representation expressing human and

business reality according to those principles and a technical design and

implementation produced from those models. First, and in order to provide the

theoretical principles that take properly into account the human element and its

behaviour, in [1] a new philosophical stance – Human Relativism (HR) – was

proposed together with an analysis of human action seen as the kernel element of any

approach following this stance. In this paper we use and extend the HR view by

introducing a new modelling approach for IS – NOMIS – that integrates the key

notions and views of three socio-technical approaches to IS, namely Organisational

Semiotics [2], the Theory of Organised Activity [3] and Enterprise Ontology [4] in a

coherent and consistent human-centred modelling approach built around the human

action element. The new vision provided by NOMIS is intended to furnish a more

realistic, comprehensive, and concise modelling of IS reality. Also, in this paper some

examples of this vision expressed by NOMIS views and some of its specific

representation diagrams will be shown applied to an empirical case study of a library

system.

This paper is organised as follows: section 2 briefly presents the theoretical

foundation of NOMIS, namely HR and NOMIS underlying theories. Section 3 makes

a brief analysis and comparison of these theories and presents the integration

principles adopted by NOMIS and its proposed modelling views. In section 4, a

library system case study is used to illustrate the application of NOMIS, in particular

some diagrams provided by each of its views will be presented. Section 5 presents

some related work regarding other attempts to integrate the foundation theories of

NOMIS and, finally, section 6 present the conclusions, work done and future work.

2 Theoretical Foundations of NOMIS

2.1 Human Relativism

Human Relativism (HR) [1] is a simple philosophical stance that recognises reality

relative to humans without adhering to a subjectivist view of the world. This view is

particularly important in businesses and organisations where the key elements are

humans that have different understanding, experience, and knowledge of

organisational reality. Also information expressed by language and used to represent

and communicate this reality has a fundamental role in this context. Again,

information is dependent on individuals and their perceptions, interpretations,

knowledge, judgment, etc being impossible to formulate and state precisely. Thus, HR

recognises and highlights the central role played by humans by acknowledging an

objective reality as human relative and proposes two concepts – observability and

precision – to deal with the unpredictability and inaccuracy factors introduced. In

order to understand the first concept – observability – is necessary to distinguish

between perception, the process of acknowledging the external reality through our

senses, and interpretation, the meaning making process. Only information goes

through the interpretation process, all other elements of human reality are just

perceived. This restricts what is perceived by humans and, consequently, what is

understood as observable. Observable things can be viewed as material or physical

18

individual things from the objectivist point of view. As an example a particular house

is observable, but the concept of a house, an universal, is not observable.

From this perspective HR makes the following assumption:

Anything that is observable will be more consensual, precise and, therefore

more appropriate to be used by scientific methods.

In practice observability intends to remove ambiguities from human reality and to

achieve the necessary precision needed to apply and use scientific methods. Besides

using observability it is also possible to remove ambiguities by having a high degree

of precision in any element of human reality. This second concept of precision in HR

seeks to deal with this matter. To have a high degree of precision means to have a

reduced level of ambiguity and different meanings in some term or element making it

generally accepted, recognised and shared. One way of achieving precision, for

example, is the use of physical measurement. It is simple to say, by using an

appropriate instrument, if a specific string has or has not one meter of length, making

it not so dependent on individuals.

From what have been said, an important Human Relativistic hypothesis is:

By adopting observable elements or high precision elements under a human

relativistic view it is possible to derive a scientific and theoretical well founded

approach to IS.

These simple ideas proposed by HR are, in fact, aligned with social constructivism

and objectivism making a proper connection between them.

From an IS development viewpoint most of the problems felt with hard and soft

approaches have its origins in the human element. This element introduces, in many

different ways, an unpredictability factor that prevents the use of scientific and

objective methods. HR identifies and highlights this point by recognising human

behaviour, in general, as the source of IS development problems. This allows for

using different approaches when human behaviour is or is not present. Therefore,

another HR hypothesis and conclusion is:

We may freely apply technical approaches if there is no unpredictable

behaviour present, specifically human behaviour.

2.2 Organisational Semiotics

One of theories supporting NOMIS is Organisational Semiotics (OS) [2] which was

introduced by Ronald Stamper and his teams. OS perspective recognises and

emphasises the social nature of IS and purposes a new philosophical stance –

actualism – as a new way of looking into the world where reality and knowledge are

constantly being constructed and altered by human agents through their acts. Human

agents and their actions are, in fact, the essential elements of the two philosophical

assumptions assumed in OS [5], namely:

(1) there is no knowledge without a knower

(2) his knowledge depend upon what he does

Or, for practical purposes:

19

(1’) there is no reality without an agent

(2’) the agent constructs reality through his actions

These assumptions were also the result of adopting and extending the Theory of

Affordances of James Gibson (1904-1979) to the organisational domain. James

Gibson was a psychologist who had formulated a radical ‘ecological approach’ to

visual perception [6]. His theory was an answer to some ideas he felt to be wrong: 1)

the notion that perception was a passive process with sensory information being just

received and processed, and 2) the environment did not contain enough information to

guide action. His answer was that perception is in fact an active process, a system that

not only receives, but also search information and assures stability of its supply,

acquiring own knowledge in this process. The perception system is able to detect

invariants from the flux of information received from the environment. The invariants

the agent recognises are those that matter for its survival or well being. This idea can

be simply described by the concept of affordance which means what the environment

can do for a creature, or what it affords the creature to do to. Affordances can be seen

as repertoires of behaviour attached to each element that an agent identifies as

invariants. OS extended this notion of physical affordance to the social world by

introducing the concept of social affordance, which analogously, enables social action

by an agent.

OS also establishes a particular dependency between affordances where an

affordance cannot exist without the co-existence of another affordance. This kind of

dependency known as ontological dependency is a key concept in OS. A selected set

of affordances and their ontological dependencies, obtained from the different agents

in the organisation, is used, in OS, to produce an ontological schema of the

organisation known as an Ontology Chart (OC) where the key business terms are

represented.

Following the social perspective adopted by OS, organisations are understood as

social systems, acknowledging a social reality where people and their social relations

play the main role. In these social systems people behave, judge, think and act

according to social norms. Norms govern the attitudes of individuals and become a

fundamental element in the living organisation. These norms are socially constructed

being learned, sustained and improved by each generation directing people to behave

in a predictable, civilised and organised way. OS defines the following general

behavioural norm structure [7]:

IF condition THEN agent ADOPTS attitude TOWARD something

The human agent having the necessary information (condition) is expected to adopt

an attitude that will trigger or influence his actions towards something.

Different groups of norms or norm systems act, in practice, as fields of forces

binding people together and determining their expected behaviour. Each individual

lives and shares different systems of norms such as those belonging to a nation,

religion, tradition, family or a particular organisation, activity or business. Groups of

people sharing a system of norms make up an information field. Stamper [8] provides

the following definition of an Information field:

“A group of people who share a set of norms that enable them collaborate for

same purpose, constitute an information field, where the norms serve to

determine the information the subjects need to apply them.”

20

Agents, affordances and its ontological dependencies, information fields and

norms are the key notions applied by OS that provide a particular understanding of

organisational reality.

2.3 The Theory of Organized Activity

The Theory of Organized Activity (TOA), thought and proposed by Anatol Holt [3] is

the second foundation of NOMIS. This theory presents a new perspective of IS based

on the concept of ‘Organized Activities’ or OA for short. This conceptual view of

TOA and OAs can be described and it is confined in the following statement:

“I intend the expression ‘organized activity’ to mean a human universal. Like

language, organized activity exists wherever and whenever people exist. It will

be found in social groups of a dozen, or in social groups of millions - in the

jungle and in New York City, in every culture, and at every stage of

cultural/technological history. It is manifest in every form of enterprise,

whether catching big game, coping with a fire, or running a modem

corporation – even acquiring and communicating by language.” [4, pg.1].

OAs are intended to form the basis for a systematic analysis of human organisation(s)

and TOA emphasises a group of aspects and components for every OA:

A common communication language – expressed not only by words, but by

actions and things as well, known as units and recognised by people sharing or

involved in the same activity. Behind this idea there is an essential and associated

metatheory called the Theory of Units (TU).

Actions – which directly affect, involve or act on things or materials. Actions are

related to a temporal dimension.

Bodies – representing things or materials, related to a material dimension.

Action Performers – always persons and/or Organisational Entities.

For planning OAs, TOA provides a diagrammatic language – Diplan [4] – where

actions, action performers and bodies are shown together with the relationships

between them.

TOA puts a special emphasis on actions that must be always human actions.

According to Holt responsibility can only be attributed to humans and therefore

computers and other tools cannot perform actions. Human actions, in TOA, are

understood as motivated and driven by the interests of their performers.

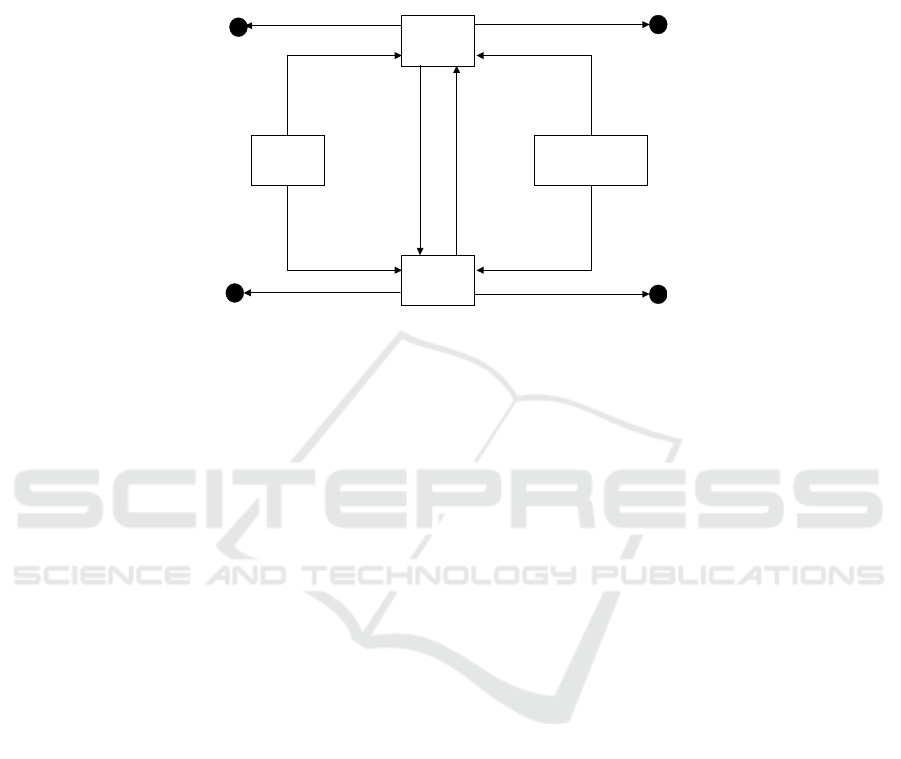

Fig.

1 defines the OA kernel which relies in two dichotomies: persons/OE and

actions/bodies. Referring to this kernel Holt states as a fundamental hypothesis of

TOA that: “all organized activities, no matter how complex and subtle, can be

usefully represented in these terms…” [4, pg. 56].

Besides TOA key concepts of actions and bodies, it also defines the concepts of

state and information. A state in TOA only applies to bodies and is only understood

within specific domains of action. This notion makes a TOA state different from the

usual technical description of a state. Regarding information, in TOA it has the

exclusive end use of making decisions, which determines the following course of

actions. Information in TOA is carried in lumps by bodies, being those lumps

21

exclusive properties of those bodies. Information contents of a body depend on the

context of its use and on the particular actors performing the actions. The same

information can be used differently by different actors or in different contexts.

Fig. 1. Organised Activity kernel [3].

TOA view of information is considered ‘a conceptual climax of the theory’. Three

statements are made [4, pg.173]: 1) it is the first and only concept of information that

relates information to human decision, 2) shows promise for the definition of

measures consistent with those of Claude Shannon, and 3) provides a basis for

explicating all real-world operations performed on real-world information.

2.4 Enterprise Ontology

The third NOMIS foundational theory is Enterprise Ontology (EO). EO is a complete

methodology comprising an ontological model, a systems theory, a model

representation and a method for its application. The essential basis of EO is the

Language Action Perspective (LAP) [9] where the essence of an organisation is seen

as the intentions, responsibility and commitment of people made with the exchange of

language acts. LAP sees language as effective action which drives and produces

changes in the world. Following LAP, EO views organisations as networks of

communicating people. In fact organisations seen at an essential level, where there is

no material or technical support, are nothing else than a group of communicating

people. At this level work is produced as a result of the exchange of language acts;

social aspects take higher emphasis than production aspects. In this sense work

production is the result of people intentions, commitments, obligations and

responsibility. This high level view of an organisation is explored in EO by focusing

in communication and coordination aspects modelled using a general communication

pattern derived from the W&F basic conversation for action. This pattern known as

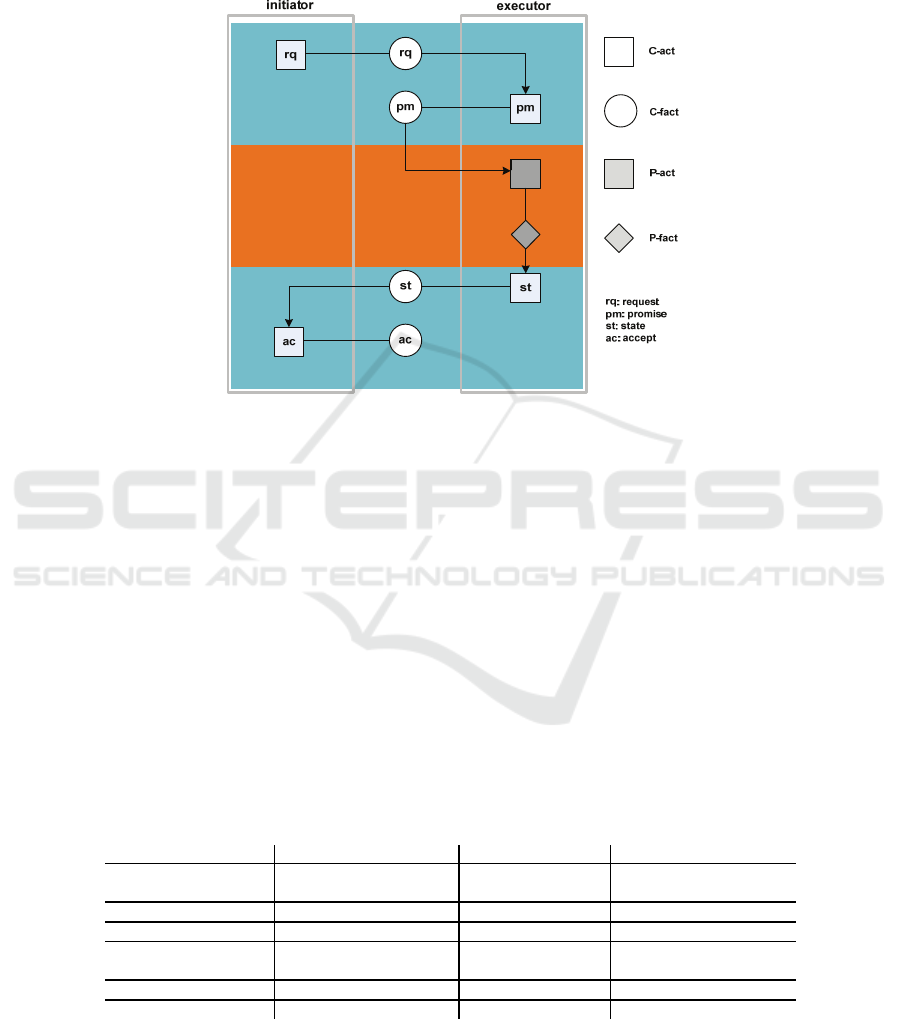

the basic transaction and shown in Fig.

2, is used to model any system or organisation

at the essential level. An extension of this pattern, which includes the exception paths

is understood as a socionomic law. In this pattern there is a clear distinction between

coordination acts (C-acts) used in conversations and production acts (P-acts) used for

ACTIONS

BODIES

ORGANIZATIONAL

ENTITIES

PERSONS

materia

l

lum ps

Time

effort

lum ps

Space

are

inv olved

in

inv olv e

are

take

take

perform

possess

perform

possess

are

22

objective action. C-acts are generally connected to commitments made by the

speakers and P-acts to material or immaterial (such as decisions) actions made by the

hearers.

Fig. 2. The Basic Transaction Pattern [10].

Besides the philosophical foundations of EO based on LAP, there is a theory - the

Ψ-theory - underlying EO that is defined in four axioms and one theorem. The first

three axioms of this theory, namely the operation, transaction and composition

axioms define respectively, the key elements modelled in EO, the transaction pattern

and two particular compositions of these patterns. The fourth axiom – the distinction

axiom – clearly establishes three different ontological levels for organisations

emphasising the application of EO to the top level known as the ontological level.

Finally, the organisation theorem completes the Ψ-theory. According to this theorem

the organisation of an enterprise is a heterogeneous system composed by three

homogeneous systems, namely the business, intellect and document organisation

systems (B-organisation, I-Organisation and D-organisation for short).

3 Analysis of the Theoretical Foundations of NOMIS

Table 1. Comparison table of OS, TOA and EO key concepts.

OS TOA EO

Focus

Organisations, agents and

behaviour

Human organised

activities

Organisations as networks

of commitments

Kernel elements

Signs Units Business transactions

Context boundary

Information field Activity World ontology

Means of conducting

business

Agent actions within a

normative scope

Human action Coordination acts and

production acts

Business performers

Agents Persons and OEs Actor roles

R-phase E-phase O-phase

23

3.1 Theoretical Core Concepts Analysis

Starting by comparing the basic assumptions of OS, TOA and EO presented in the

previous section we found a similar perspective of the world and how it is

experienced. In fact those theories share, as most soft approaches, the social

constructivist stance view where reality is socially constructed. An IS according to

these theories is understood as a network of people where connections are established

by human actions, interactions and communication. A social dimension where

individuals are related to each other and to their environment is always considered.

Regarding the instruments used to carry out the business and considered by each

theory, we found linguistic and non linguistic actions performed by humans at the

kernel of all of them. Whereas OS and TOA are based on general human actions, EO

emphasises language acts, also human actions. One of the reasons for including only

actions performed by humans has to do with the responsibility factor attached to those

actions. Effectively, responsibility is a key concept in all these theories. To this

concept, OS puts some emphasis also in authority, TOA in the interest of the human

performers and EO in the intentions of those performers.

Besides those common assumptions of centred human based information systems,

there is another common aspect concerning people, their actions and their acting

environment: awareness and grounding of the context. Whereas TOA uses the activity

as a defining context for any performed action, OS defines an information field as the

context to which everyone is subjected in a world of norms and social behaviours.

EO, on the other hand defines the context by acknowledging a world ontology defined

by each system, usually an organisation.

Another two important and related concepts within IS are meaning and

information. Bounded by context in the theories, ‘meaning’ in TOA is shared,

dynamic and socially created, being established by the TOA unit concept. In OS

‘meaning’ is imported from semiotics through the sign concept. From the semiotic

perspective a TOA unit is a socially established sign, whose meaning can be defined

and socially validated using a criterion. Meaning in EO is established according to the

ontological model represented by the EO ontological parallelogram. This model

applies to a system or organisation as a world ontology defining the meaning context.

The second concept of ‘information’ is obtained by interpretation in EO and

carried by language, in a broad sense, in LAP and by semiotic signs in OS. TOA has a

different and particular view of information: “… it is always carried by bodies”, and it

“… is a kind of human resource, as essential as energy”, which “end-use is in the

making of decisions” [3, pg.130-131]. This means that information is useless, except

for the making of decisions that can be a simple decision to act.

One last common and important aspect found in TOA, EO and OS is the role of

technology as supportive to business systems or organisations, or else to systems of

people as they are understood.

Concerning the relevant differences between the theories, they occur specially

through the use/planning of human acting within any business or organisation. EO is

based on language (as) actions for conducting business operation delegating other

actions to a secondary level. On the other hand, TOA is strongly based on human

actions of any kind involving always some material resource (a body). OS uses agents

for doing the action according to a well formed formula where agents and actions are

always present. In OS these actions are regulated by norms. An essential difference

24

regarding OS is that OS do not put the focus on how actions are conducted or on their

effects but, emphasises the necessary conditions for actions through the affordance

concept. A comparison table summarising the key ideas of this comparison is

presented in Table 1.

3.2 A Path for a New Modelling Approach for ISD

The previous analysis of OS, TOA and EO show that there are some commonalities

and some complementarities in them. Nevertheless, all of them provide innovative

views of information systems supported by strong theoretical foundations. In spite

their different views they share the same foundational basis: they all see the world

under a constructivist philosophical stance, understanding information systems with a

focus on individual and social aspects. This focus has also a common basis: the

human action. TOA uses human actions as the drivers and kernel of activities. In EO

there is a focus on communicative acts, which can be seen as a special case of human

actions. On the other hand OS focus on affordances, but affordances are a kind of

environmental states that afford human actions. Also in OS human action is a key

term present in the universal well formed formula and in norms. The concept of

human action is really a shared and connecting point between all these theories

although they provide different views and use for human actions. Interestingly these

views are in some way complementary. EO looks into communication aspects, TOA

sees the effects of actions in bodies and as a consequence, action sequences and OS

look into the necessary conditions for actions or what affords actions. A more

comprehensive model of an IS could use all these views in a coherent way to provide

an improved and comprehensive representation of the reality being modelled.

Getting back to the social constructivist view adopted by each theory there is

another aspect related to this view that is common and adopted in TOA, EO and OS –

the individual understanding of the basic activity terms within a social shared context.

This is materialised by the unit concept within the activity context of TOA and the

affordance terms related to the information fields in OS. EO uses a world ontology

applied to systems to establish the social context. From this common perspective all

terms should be understood relatively to its social context. In OS an information field

defines the context for meaning, in TOA the context is provided by an activity and in

EO it is established by an organisation or system. It is possible that the same terms

will be used and understood differently in different contexts in these visions.

Another key concept adopted by OS is the norm concept. Norms are used by OS

as a kind of force governing attitudes of people. In OS a group of norms define an

information field. In particular, behavioural norms govern people actions. This is

another transversal concept that can be used also in TOA and EO. However EO also

defines a kind of norms that are expressed as action rules. These are in fact norms

although they are only applied within the context of coordination acts.

One issue relating these theories is their particular understanding of information.

OS relates information to the semiotic sign, whereas in TOA information is used for

the making of decisions. EO adopts in some way the semiotic view of OS within its

‘ontological parallelogram’ [3].

From the perspective of action performers all the theories share a common

understanding: OS uses the human agent, TOA the human performer and EO the actor

25

being all of them a representation of the same concept. In these theories an agent may

be an individual or an organisation and responsibility is assigned to this agent

accordingly. The other related concepts assigned to individuals and used in the

different theories, namely interests, authorities, commitments, intentions can all be

used concurrently without clashing to any fundamental aspect of them.

From a practical point of view for the structuring of information systems, TOA

gives a good and practical perspective by focusing on activity decomposition of IS,

which is also a natural way to understand and organise an IS.

In conclusion, a possible integration of the powerful and well grounded views of

OS, TOA and EO promise to be a better representation of the reality that should be

further explored.

4 The NOMIS Modelling Approach

4.1 Introduction

One of most important barriers to objective and successful design, development and

implementation of technical IS has to do ultimately with the unpredictability factor

introduced by the human element. HR showed a possible way to overcome

unpredictability with the concepts of observability and precision. Effectively,

unpredictability within IS is directly related to human behaviour where charcteristics

like intentions, meanings, responsibilities, feelings, decisions, judgments, interests,

values and many others are difficult to describe, to predict or to control. Part of this

behaviour is observable; it is possible to see or to hear what each individual does or

talks. These are the human actions. From this perspective human actions is defined

here as the expression or externalisation of human behaviour, or the observable part

of human behaviour. According to the HR assumption that “anything that is

observable will be more consensual, precise and, therefore more appropriate to be

used by scientific methods” human actions should be an ideal element to be

incorporated and used as the centre of analysis, design and modelling of an IS. This

conclusion is fully aligned with the perspective of the theories analysed in the

previous section. As was pointed before, each of them takes human action as a central

element of their view.

This approach leads us also to think in the role of IT as a tool extending human

capabilities by facilitating, improving, expanding and complementing human action.

Although human action appears to be an ideal basis for IS modelling, it also

introduces a link to human behaviour which is difficult to deal with. A solution for

this problem is already provided in OS through the use of norms. Norms, particularly

behavioural norms, give the possibility to deal with human behaviour by describing

‘expected’ human behaviour. Norms act as fields of forces that make people tend to

behave or think in a certain way. OS also uses the Information Field paradigm to

describe different systems of norms that are shared and applied in different

communities. These communities are composed by individuals belonging or acting

within the same normative system. To identify and to take into account each

normative field and the important norms regulating them and influencing human

behaviour should be seen as a step further in the development of successful IS.

26

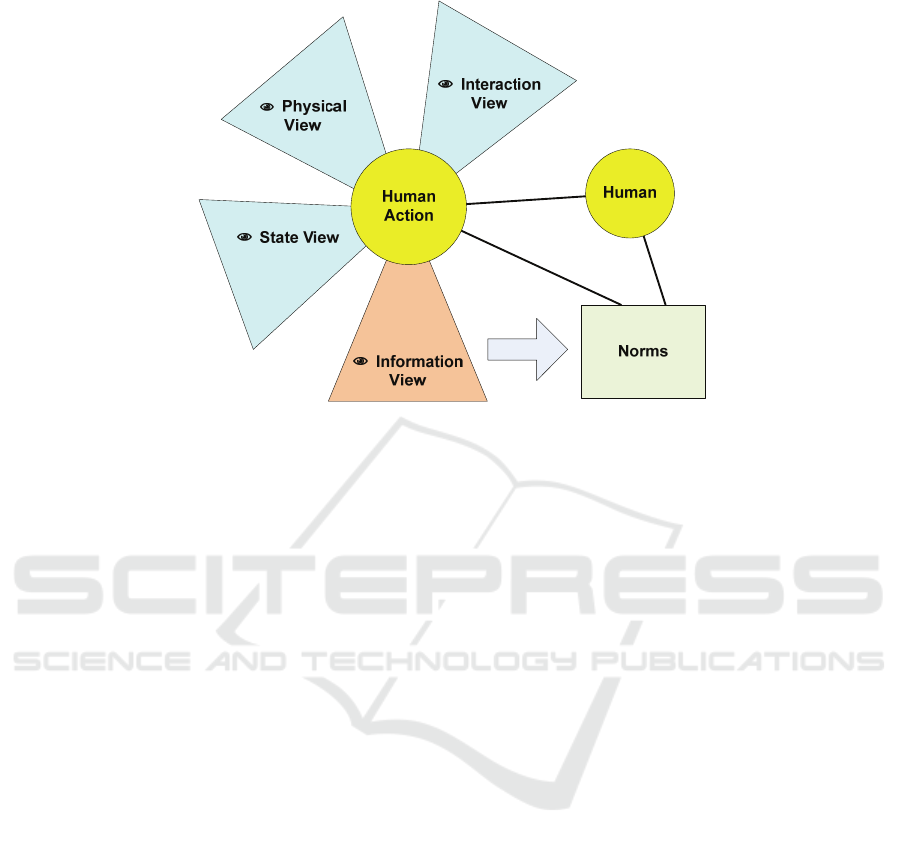

Fig. 3. The NOMIS modelling approach.

The previous view based on human actions, norms and information fields, which

is guided by the HR philosophical stance is the basis of NOMIS, an acronym for

NOrmative Modelling of Information Systems, introduced here as a new modelling

approach for IS. Following this perspective NOMIS defines four separated views into

the IS reality, namely the physical view, the state view, the interaction view and the

information view. The first three views reflect the visions and perspectives of,

respectively, TOA, OS and EO in which NOMIS is based. The last complimentary

view relates to the important information dimension uncovered in the previous

analysis. A simple picture expressing this structure is depicted in Fig.

3.

In the following sections each of the views proposed by NOMIS vision and its

normative aspects will be briefly presented.

4.2 The Interaction View

The first view NOMIS proposes is the interaction view. The interaction view covers

the communicational dimension of human action. All interactions involve

communication and communication itself is a form of interaction. Any business or

organisation is driven by a network of people performing actions coordinated by

communication; interactions link people. From this perspective it is important to draw

a special attention in how people interact and in particular communicate.

This view covers the language-action perspective of EO and LAP and extends it.

By focusing on interaction aspects of human action, in particular human

communication, this view is expected to capture the essential aspects of any business

and organisations as EO sees and understood it. Furthermore, EO uses a single

business transaction pattern to model organisations that translates to a coherent,

consistent and sequenced group of specific communication acts and production acts.

Although this pattern may be used and shown using this view, NOMIS perspective is

27

not restricted to a single pattern and other types of interaction patterns, possibly based

in the richness of language acts types described in [9], are accepted to be used and

represented.

In this view the different aspects involving interaction, such as who are the

communicating actors, what interactions they perform, what communication links or

channels connect them, and other observable aspects that may be addressed and

represented.

4.3 The State View

The next NOMIS view is the state view. This view looks into environmental

conditions and dependencies between them that enable an agent to act. This is the

perspective of OS. The environment, including the appropriate elements, enables or

affords the agent the ability to execute an action. These situations that NOMIS

designates as environmental states (ES) and that the agent identifies as invariants, OS

calls them affordances and shows them together with their dependencies in Ontology

Charts.

A difference concerning OS is that environmental states defined in NOMIS and

related to the affordance concept do not have to follow completely the rules

established for Ontology Charts and, thus may avoid some of the problems related to

its use. ESs, as defined in NOMIS, are composed by a body, or an information item,

or a group of different bodies and information items in a particular state. The elements

composing an ES have some observable form that may include information by using

its representation. Nevertheless, ESs usually represents essential business states

related by ontological dependency to other ESs and/or bodies and information items.

The focus on states provided by this view surely is more stable than any focus in

sequences of actions. A perspective also defended in OS related to OCs.

4.4 The Information View

The NOMIS Information view covers the information dimension of human action.

The importance of information is recognised by all IS theories and its significance to

human action should be emphasised. Most of human actions depend or rely on

information in different ways. Some of them cannot even be performed without it.

Therefore the identification of the important information required for each action

must take special attention. There are some assumptions NOMIS makes in alignment

with the theoretical background provided by its philosophical stance and foundations:

(1) information does not exist without a material support, a body or a human actor and

(2) information can only be created by humans or instruments and can only be

consumed by humans. From a human action perspective there is a focus on what

information is required or consumed by the human performer, what information

he/her has access and what information he/her produces. From a design perspective it

would be important to furnish all information that might be useful for the action. In

this sense this view may be used to present the information needed and the underlying

system responsible to furnish it to each or to a determined group of human actions.

This would be the case of an awareness system.

28

Information is also used in Norms where it is related to agents and human actions.

This is another aspect attributed to this information view - to identify and represent

the information needed by norms.

Semiotics is a valuable help in this view for understanding information, how it is

produced and how it is represented.

4.5 The Physical View

In NOMIS physical view, attention is focused on the material and observable aspects

related to human action. This view covers the material dimension of human action

expressed by TOA. Therefore, it addresses the relationships between bodies and

actions: how bodies are affected by actions, how bodies are transported between

actions. There is also a need to understand the role of bodies within each action. The

same body may play different roles in respect to the action where it is used. A

calculator may be used as a tool to help human make operations but can also be used

as a simple material for a shop that sells it.

Physical context is another aspect of the material view that can be analysed from a

physical perspective. Specific locations (space and time) are many times used for a

group of actions; therefore it is useful to look for actions executed in a determined

location. From a design viewpoint it will be possible to provide that location with the

necessary tools, documents and instruments to help action execution.

A particular representation of this view could be an overall single action view

where all the elements related to a particular action would be represented. This would

allow thinking further into the human needs related to that specific action.

A last representation under this view that was not covered by the previous views is

business processes representations showing action sequences. This type of models is

most useful and common although under NOMIS approach shows different elements

and follows different rules. As an example in NOMIS only human actions may be

included, action sequence relates to expected behaviour regulated by norms and the

initial situation before entering an action and the final situation next to leave it

represent states of the environment.

4.6 Modelling Norms and Information Fields

The NOMIS views described previously shown a coherent and comprehensive view

of IS centred in human action and information. Each of them offers a different

perspective, however they are related in a consistent model of the IS. In fact, the

elements shown and represented in each view must be the same. A coordination act is

a human action and can be used in all the views, the same should happen for any other

human action, body, human performer and information item. In spite this connection

points NOMIS also uses the OS norm concept to regulate human actions and provide

a way to model expected behaviour. In this case, only behavioural norms, which are

related to human actions, are used. Cognitive, perceptual and evaluative norms related

to people’s beliefs, perceptions and judgements belonging to the intersubjective

domain and difficult to use in practice are not included. Behavioural norms are

represented analytically in a semi formal way as defined in OS.

29

With the purpose of helping to structure and to organise norms NOMIS proposes

the use of a simple distinction between trigger norms, required norms and auxiliary

norms related to the end use of the information from the norm condition part. Trigger

norms are related to information that causes a human action to occur, required norms

to information essential to the performance of an action and auxiliary norms to

information auxiliary to an action execution.

Besides regulating human behaviour, groups of norms are used to establish

information fields (IFs) where terms are understood by the community living under

them. This notion imported from OS is used in NOMIS to define the boundaries of

the terminology used in a particular IS. This idea is also in line with the theory of

units from TOA, where each term is understood and defined by a criterion used and

maintained by a community under a particular activity. In TOA the activity defines an

information field. In other words, each IF defines and has a proper ontology.

5 Using NOMIS to Model a Library System

5.1 Introduction

The case study that will be used in this section is an empirical case study of a library

system that is presented and described in [3]. In this library system the main emphasis

goes to the registering process where anyone can become a member of the library.

This membership state allows a member lending books, the second important library

process. These two processes, their details and rules together with other information

requirements are the essential elements of the library system case study. For the

purpose of this section it is not necessary to look into the details of the library system

although a complete description can be found in [3].

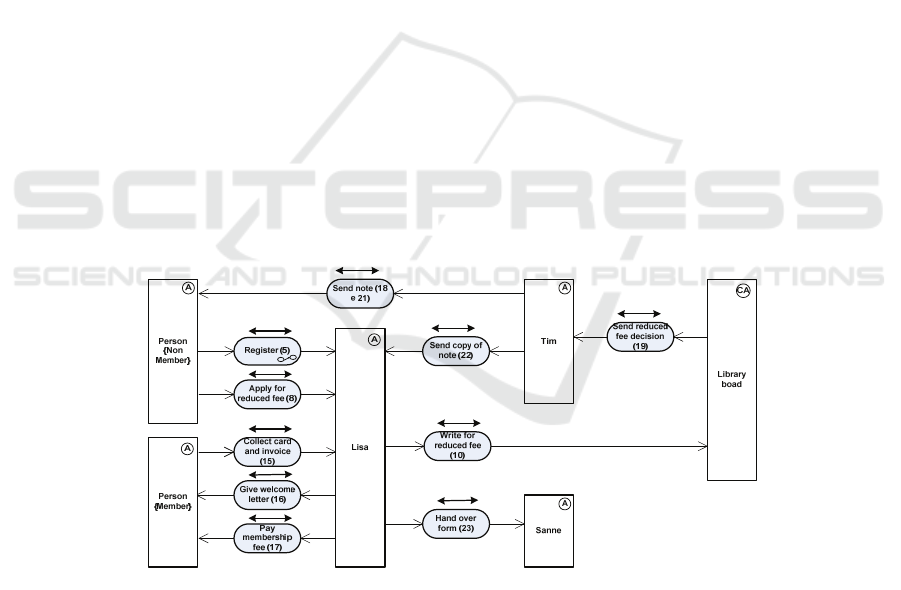

Fig. 4. The HID of the library registering process.

An additional note in this section regards the representation of NOMIS and its

vision materialised by NOMIS views introduced in the previous section. In this sense

NOMIS proposes a specific notation that defines the elements to be used for

representing NOMIS views and suggests a set of diagrams for showing the different

30

perspectives according to each of them. In this introduction only a few examples of

these diagrams will be shown for illustrative purposes. These diagrams will not use

directly the NOMIS notation but a representation of some of its suggested diagrams

using an extension of the Unified Modelling Language (UML) [11].

5.2 Interaction View

The NOMIS interaction view models the different interactions between individuals

emphasising communicational aspects. A key diagram in this view is the Human

Interaction Diagram (HID) that shows actor roles and the interactions linking them.

Figure 4 presents a HID produced for the library case study. In this diagram we see

the different interactions between actors and also interaction activities such as in the

case of ‘register (5)’. In fact, it is possible to represent groups of related actions as

interactions and to use also templates or patterns of those actions. The HID used here

is ‘compatible’ with the Actor Transaction Diagram used by EO although it may

describe other types of business transactions (interaction activities patterns). This

view covers the vision of LAP into the business reality by addressing language acts

and other forms of communication and interactions. The HID shown here is just one

of the possible diagrams used to express this view. Another type is, for example, the

Action Sequence Diagram showing action sequences, in this case mostly composed

by language actions.

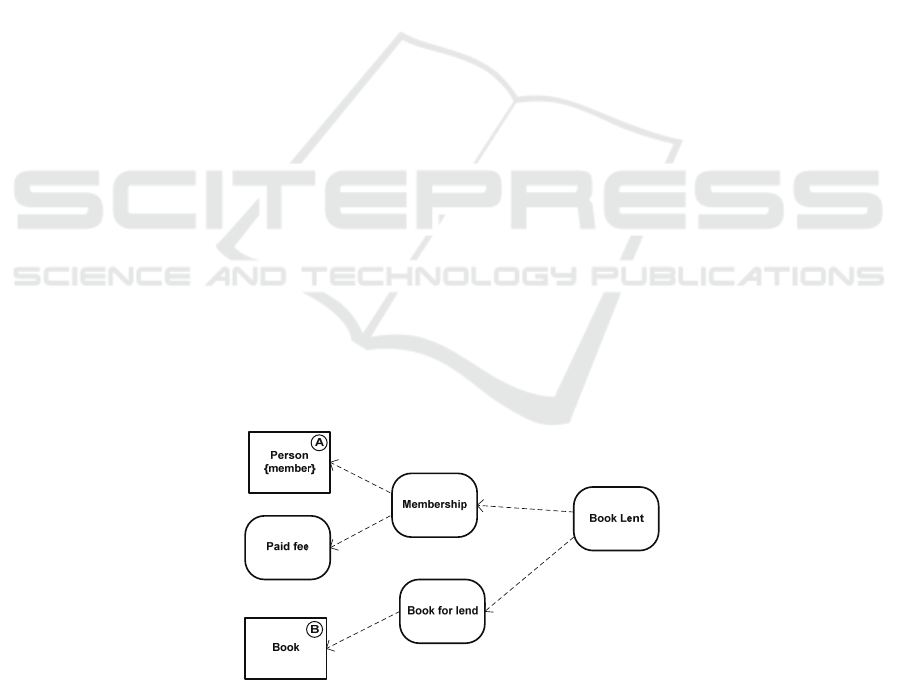

5.3 State View

NOMIS state view identifies key environmental states and the existential

dependencies between them. Each environmental state (ES) enables a particular group

of actions to occur. This acts like an OS affordance and, in fact, produces a similar

business and organisational view to the one produced in OS using Ontology Charts. A

key difference is that ES may include more than one element and the elements

included should be part of the elements modelled by NOMIS namely bodies,

information items, actors and other ES. For this view NOMIS uses the Body State

Diagrams (BSD) to show the different states of a body and the Existential

Dependency Diagram (EDD) showing ES and its existential dependencies.

Fig. 5. The EDD of the library.

31

Figure 5 shows the EDD of the library system. It is interesting to note that the

main activities of the library case are included in this diagram related to the key ESs.

This is something that is defended in the OS view regarding OCs representing the

important business concepts. Although similar, EDDs do not translate directly to OS

OCs but the view they convey is in some way similar, capturing the essence of OS

vision in this respect.

5.4 Information View

NOMIS information view identifies and models the information elements – the

information items – used in a system. Besides this identification many other aspects of

information are addressed here namely the information related to each human action,

the production, access and consumption of information by each human actor and the

supporting bodies of information. In the case of the library system most information is

identified and represented in tables without a diagrammatic representation. However

NOMIS suggest an Information Connection Diagram (ICD) to show key human

actions where information is produced, accessed or needed.

5.5 Physical View

NOMIS physical view concerns the material aspects of human action. One possible

model representation under this view is the life cycle of a particular body through the

human action sequence in which it participates. In the case of the library, we took as

an example the registration form and a Body Action Diagram (BAD) was created

showing the registration form lifecycle (Figure 6). This diagram is a kind of a UML

Activity Diagram showing actions, their sequence and bodies in particular states. This

is the view produced by TOA using an action sequence perspective being this diagram

compatible with TOA Diplans. BAD provides a typical representation of a business

process although the main elements are human actions having always behind a human

actor. These are the real business processes according to NOMIS Vision and their

foundation theories. Besides BAD diagrams this view provides also ASD showing

action sequences as mentioned before and Action View Diagrams (AVD) for detailing

each action individually.

5.6 Information Fields and Norm Analysis

Besides the views produced by NOMIS also information fields (IF) and norms are

addressed by NOMIS Vision. In the library case study the library system was

considered as a single IF but in some cases is necessary to consider different IFs. In

each IF there is a common form of expression and communication that may differ

between them. NOMIS views can express IFs as areas in the diagrams and it is

important to represent them in each system.

Regarding norms, they regulate human behaviour, in particular, human actions.

One important use of norms in NOMIS vision is as action sequence determiners.

Effectively, any action sequence is regulated by norms, humans may decide to not

32

follow these norms, and thus the sequence is not rigid. Another use of norms is to

establish the dependencies of an action on their elements including environmental

states. In general, there is a key principle that applies to all norms: ‘Any norm has a

subject and an action element’, therefore they are just understood and applied in

context of human actions. Norms represent the most extensive group of elements of

an information system.

6 Related Work

The integration proposed in this work of TOA, OS and EO has never been proposed

before although there are a few attempts regarding OS and EO or LAP as the EO

broader field. TOA, as a baby theory, remain relatively unknown with no much

research work produced. Thus, it was not integrated or even related to OS and

EO/LAP in any research as far as the authors know. In the case of OS there are

already a few links to LAP notions. Effectively, affordances depicted in OC may

represent language-acts seen as semiotic signs standing for something else. In [12]

Ronald Stamper addresses this fact by referring to the semantics of communication

acts in the context of OS and OCs in particular. In this case it corresponds just as a

perspective of LAP under an OS view and not a different use of both views as

NOMIS proposes.

In [13] there is an acknowledgment of the power of the different views provided

by OS and LAP and a proposal to integrate the semantics of OS with the pragmatics

of LAP. However this integration is made in a different level without considering the

different kernel elements used by NOMIS. Effectively, OS and LAP act together in

the identification of requirements that are afterwards modelled by EO/DEMO

business transactions resulting in a final LAP based only modelling.

[14] also proposes an integration of OS and LAP with the RENISYS Method but in

this case the integration uses mainly OS NORMS and LAP conversational

transactions lacking the broad integrating coverage of NOMIS.

In [15] there is another integration proposal that uses OS norms for extending the

business process models defined with DEMO, and OS semantic analysis to help

uncovering those norms.

Besides those integration proposes we found are some other minor contributions

but all of them fail in the integration broadness, strength, theoretical foundation and

extension with respect to NOMIS.

7 Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presented NOMIS, a normative approach to information systems

modelling, as a new way to understand and model information systems based on

Human Relativism. NOMIS approach joins and extends the views of Organisational

Semiotics, the Theory of Organized Activity and Enterprise Ontology in a

comprehensive and coherent way and provides a broader and accurate vision of

organisational and business reality. These views describe NOMIS vision that is

33

represented by a proper notation not described in this paper. Also, a case study of a

library system was presented and modelled using NOMIS that intended to illustrate

NOMIS vision and give a simple idea of its application.

Regarding future work, the way NOMIS sees IS has never been applied before to

the development of information systems although there are a few applications of its

foundational theories. This opens a lot of possibilities for future work: the approach

needs to be tested and developed further in real contexts. Many fields such as Human

Computer Interaction, Ontology Engineering, Business Processes Management and

other have to be reanalysed from a NOMIS perspective with possible contribution in

both directions. A missing element in NOMIS is a methodology for information

system development. NOMIS just proposes a modelling approach that enables the

representation of information systems but the way from this representation to the

development of concrete information systems is still needed. Besides methodologies

NOMIS modelling requires tools as well. For the representation of NOMIS models it

will be necessary to develop tools that will allow for verification and validation

support of developed models.

In conclusion, much work can be done as future work within this new NOMIS

approach that will be essential and necessary for its success.

References

1. Cordeiro, J., Filipe, J. and Liu, K.: Towards a Human Oriented Approach to Information

Systems Development. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Enterprise

Systems and Technology. Sofia, Bulgaria (2009).

2. Liu, K.: Semiotics in Information Systems Engineering. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK (2000)

3. Holt, A.: Organized Activity and Its Support by Computer. Kluwer Academic Publishers,

Dordrecht, The Netherlands (1997)

4. Dietz, J.: Enterprise Ontology, Theory and Methodology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg, Germany (2006)

5. Stamper, R.: Signs, Norms, and Information Systems. In Signs of Work, Holmqvist B. et al

(eds). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany (1996).

6. Gibson, J.: The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Houghton Mifflin, Boston,

(1979).

7. Stamper, R.: New Directions for Systems analysis and Design. In Enterprise Information

Systems, Joaquim Filipe (ed). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands,

(2000).

8. Stamper, R., Liu, K., Sun, L., Tan, S., Shah, H., Sharp, B. and Dong, D.: Semiotic Methods

for Enterprise Design and IT Applications. In Proceedings of the 7th International

Workshop on Organisational Semiotics, Setúbal, Portugal, (2004).

9. Winograd, T., Flores, F.: Understanding Computers and Cognition. Ablex Publishing

Corporation, Norwood, NJ, USA (1986).

10. Dietz, J.: The Deep Structure of Business Processes. In Communications of the ACM, 49,

5, pages 59 -64, (2006).

11. Booch, G., Rumbaugh, J. and Jacobson, I.: The Unified Modeling Language User Guide.

Addison-Wesley, (1999).

12. Stamper, R.: Exploring the Semantics of Communication Acts. In Proceedings of 10

th

International Working Conferenceon the Language Action Perspective. Kiruna, Lapland,

Sweden, (2005).

34

13. Shishkov, D., Dietz, J. and Liu, K.: Bridging the Language-Action Perspective and

Organisational Semiotics. In: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on

Enterprise Information Systems, Paphos, Cyprus, (2006).

14. De Moor, A.: Language/Action Meets Organisational Semiotics: Situating Conversations

with Norms. In Information Systems Frontiers 4:3, 257–272, (2002)

15. Barjis, J., Dietz, J. and Liu, K.: Combining DEMO Methodology with Semiotic Methods in

Business Process Modeling. In Information, Organisation and Technology. K. Liu, R. J.

Clarke, P. B. Andersen and R. K. Stamper (eds). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston,

pages 213-246, (2001).

35