HYBRID ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS

Tiago Pedrosa, Rui Pedro Lopes

Polytechnic Institute of Braganc¸a, Braganc¸a, Portugal

Jo

˜

ao C. Santos

DEE, Coimbra Institute of Engineering, Coimbra, Portugal

Carlos Costa, Jos

´

e Lu

´

ıs Oliveira

IEETA, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords:

EHR, PHR, Mobility, Hybrid EHR.

Abstract:

The research related with digital health records has been a hot topic since the last two decades, producing

diverse results, particularly in two main types – Electronic Health Records and Personal Health Records. With

the current wider citizen mobility, the liberalization of health care providing, as well as alternative medicine,

elderly care and remote patient monitoring, new challenges had emerged. These brought more actors to the

scene that can belong to different healthcare networks, private or public sector even from different countries.

For creating a true patient-centric electronic health record, those actors need to collaborate in the creation and

maintenance of the record. In this work, the Hybrid Electronic Health Record (HEHR) is presented, describing

how information can be created and used, as well as focusing on how the patient defines the access control.

Some new services are also discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital health records has been under development on

the last two decades, focusing on two type of records

– Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and Personal

Health Records (PHRs). The EHRs were defined and

deployed mainly to cope with the requirements of the

healthcare providers without considering the patient

needs on the process. PHRs were created to enable

a more active role by the patient in the creation and

maintenance of his health record.

The idea of achieving a longitudinal patient-

centered record that can enable health professionals

to have an integrated view of the patient’s clinical

history is still an open challenge (Smith and Kalra,

2008). The liberalization brought a wide number of

actors into healthcare provisioning, offering new pro-

cedures (Chanda, 2002) (enabling the patient to have

free choice of the healthcare provider, access to new

types of complementary and alternative medicine,

among others). Also the citizen’s mobility has in-

creased, either for professional, personal or medical

reasons (EESC, 2007), leading to a huge number of

different healthcare providers, public, private, feder-

ated, isolated, from different countries. Meanwhile

the patient requires a more active role, controlling the

access to his medical information and contributing to

his record without compromising the choice of his

healthcare provider (Eysenbach, 2008).

In order to achieve a record where all the ac-

tors could collaborate, this paper describes the Hybrid

Electronic Health Record (HEHR), and how it is used

in the creation of information, access control and new

services support.

2 EHR VS. PHR

To clarify the HEHR, we begin by analysing the two

main streams of records, EHRs and PHRs. The EHR

can be described as a longitudinal storage of patient

health information generated by one or more encoun-

ters in any care delivery setting (HIMSS, 2010a). This

information may include several kinds of data such

571

Pedrosa T., Lopes R., C. Santos J., Costa C. and Oliveira J..

HYBRID ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS.

DOI: 10.5220/0003167605710574

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2011), pages 571-574

ISBN: 978-989-8425-34-8

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

as patient demographics, progress notes, problems,

medications, vital signs, past medical history, immu-

nizations, laboratory data, and radiology reports. The

EHR has the ability to generate a complete record of a

clinical patient encounter, as well as supporting other

care-related activities directly or indirectly via exter-

nal interfaces.

The information on EHRs is produced by health-

care professionals and maintained by the health-

care providers, following four types of models: the

fully federated, federated, service orientated and in-

tegrated (NCRR, 2006). Moreover, each deployment

in each country/region or federation uses different ap-

proaches under different regulatory frameworks, This,

plus the lack of a well defined standard makes inter-

operability difficult (The Lancet, 2008).

EHRs are mainly devoted to facilitate the work

and information flow between different departments

of an institution or a federation. They also try to

manage administrative information related to the ad-

mission, discharge and payments (The Lancet, 2008).

This approach excludes any patient intervention, in-

cluding the requirements analysis. In other words,

it is a solution to cope with healthcare profession-

als needs, inside a well-defined group of actors, sup-

ported by agreements between them, to share patient

clinical related information.

PHRs can be described as an lifelong tool for

managing relevant health information of an individ-

ual (HIMSS, 2010b). It promotes personal informa-

tion maintenance and may be used in a broader scope

or in more specific scenarios, such as chronic dis-

ease management. The PHR is owned, managed and

shared by the individual or a legal proxy(s).

Although different types of PHR have been devel-

oped the most relevant are: the standalone, resident in

some external store device (Santos et al., 2010), and

the web-based. The most prominent web-based PHR

are Google Health, Microsoft HealthVault and Dos-

sia. These web-based PHRs are generally based on a

central repository and on a set of core features that, in

some cases, can be extended by third-party services.

Table 1 resumes the main differences between

EHRs and PHRs. According to the definitions and the

method of deployment of those types of records, the

PHR seams to better cope with most of the needs, as it

enables the easily sharing between different actors de-

spite of their location, agreements and depends on pa-

tient approval. It also solves the problem of the infras-

tructure cost, as the patient chooses a PHR provider.

It also empowers the patient to maintain and control

the access to his medical record. One drawback is the

trust by the clinical staff on the integrity of the clinical

information.

Table 1: EHR vs. PHR.

EHR PHR

Guardian Providers Patient or a service on his

behalf

Creation of data Medical Staff Patient or exported by ser-

vices

Sharing Institutional

agreements

Patient choice

Access Control Provider Controlled by the patient

System Provider Providers External Service Provider

The EHR has the trust of the medical staff how-

ever, record sharing is difficult. It also restricts the

patient freedom of choice, since he is dependent on

the agreements that providers have in other to access

his medical information. In this scenario, the patient

is a passive actor, since he cannot contribute to his

record, and cannot control the access to his medical

information. Mobility and EHR harmonization have

been discussed previously (Pedrosa et al., 2010).

3 A NEW PROPOSAL FOR A

HYBRID EHR

The Hybrid Electronic Health Record appears as a so-

lution to overcome the problems identified previously,

enabling the free collaboration of all the actors, con-

trolled by the patient and with medical data integrity

control. The hybrid approach tries to combine the

best characteristics of the EHR and PHR, supporting

contributions from several actors, and allowing access

control by the patient, without dependency on agree-

ments between healthcare providers.

For enabling the HEHR all actors are required to

generate a report, considered as a contribution to the

EHR. Those contributions can be generated from the

already deployed systems, from user input or by spe-

cialized services. The aggregation of all contributions

results in the patient-centric longitudinal electronic

health record.

The HEHR is based in a centralized repository,

trusted by the patient, to deposit all the contributions.

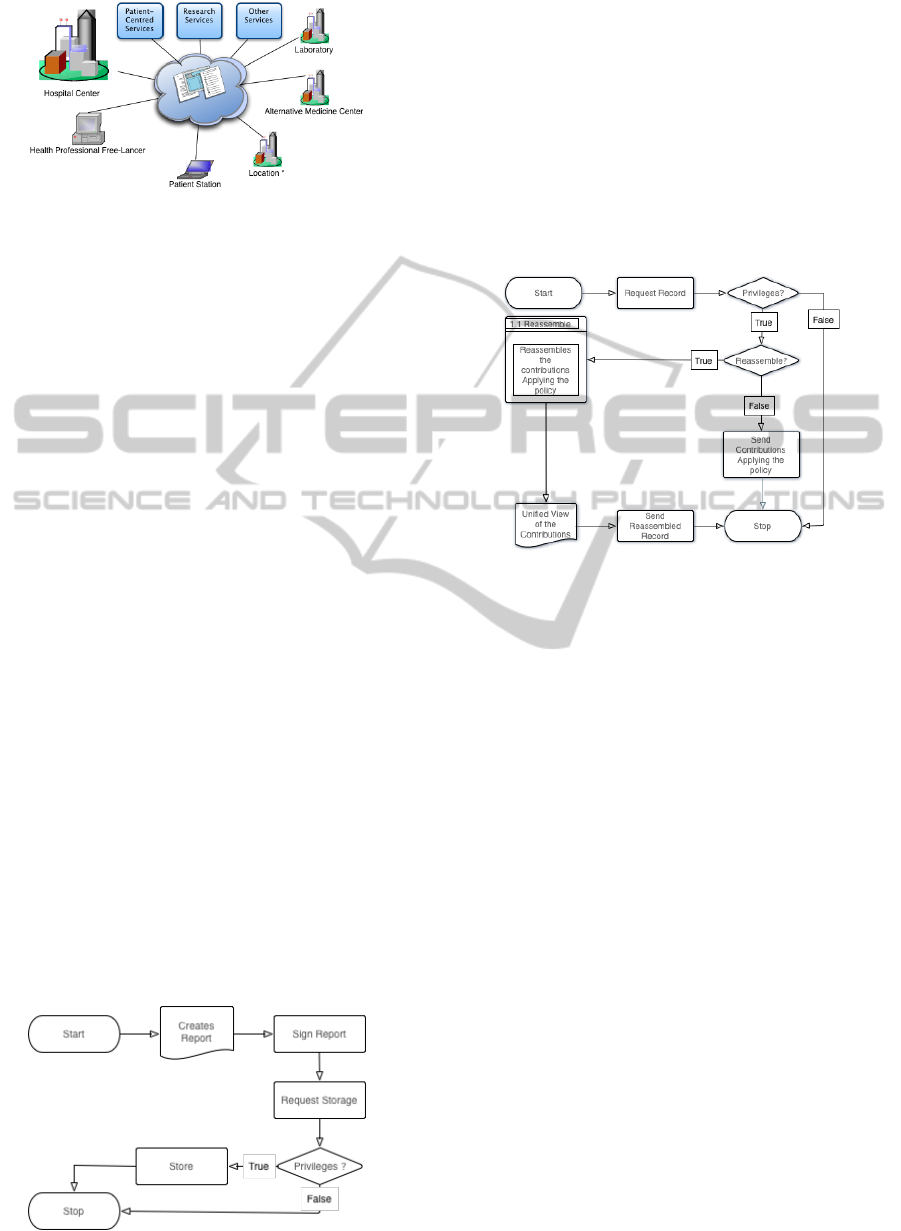

The collaboration of all the actors is illustrated on Fig-

ure 1.

The access control is performed through the pa-

tient station, where he can also create contributions.

Healthcare providers, such as hospital centers, labo-

ratories and other medical centers, can contribute as

well, exporting reports from their systems or using ex-

ternal services. Every contribution must be previously

authorized by the patient. New services can manipu-

late the information as patient centered-services, e.g.

prescription alarms or other treatment alarms; scien-

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

572

Figure 1: HEHR actors.

tific research, when allowed by the patient; and other

new services that can bring added value to the use of

patient clinic information.

Each new producer or consumer that wants to gain

access to the patient EHR requires patient authoriza-

tion. The clinical integrity of the contributions can be

confirmed, increasing the trust on the system by the

healthcare professionals.

3.1 Use Cases

On this type of record, three types of operation should

be explained: the deposit of a contribution, the request

of the record and how a new service can make use of

the HEHR.

The operation of deposit of information can be

decomposed in three steps (Figure 2). First a re-

port in a standard format, such as CDA (Dolin et al.,

2006), CCR (Ferranti et al., 2006) or OpenEHR

archetypes (OpenEHR, 2007) is generated. Then

those reports have to be signed by the producers to

ensure integrity and traceability. The last step is the

deposit of the information on a repository chosen by

the patient, if the requester has enough privileges.

Scenarios with already deployed EHR systems

should be able to generate the reports, sign and de-

posit in a seamless way. As an alternative, a local

service could perform those steps on the healthcare

provider behalf. If the provider doesn’t have a de-

ployed system, he can choose a service provider to

create the contribution.

Figure 2: HEHR store procedure.

The retrieval process is explained in Figure 3. The

actor requests the full record or parts of it. Then, the

system checks the requesters’ privileges and checks

wether the requester wants the contributions individ-

ually or assembled as a unique view. Then the pre-

viously defined policies, created by the patient, are

applied on the contributions set in order to create a fil-

tered view for the requester. The possibility of asking

for the contributions before unification allows creat-

ing custom views associated with a navigation model.

The process of requesting access to the HEHR is de-

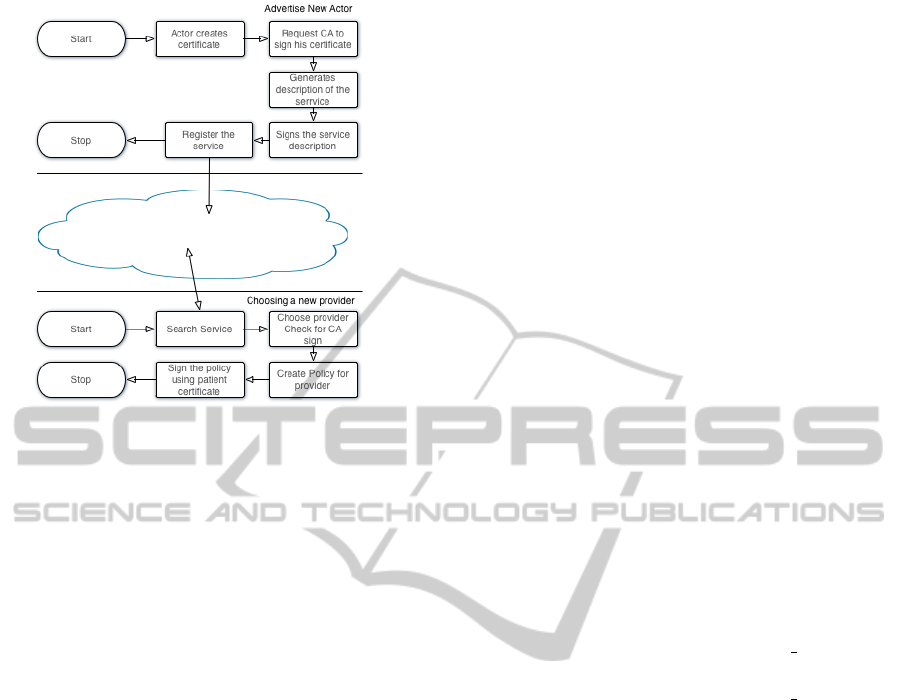

Figure 3: HEHR retrieve procedure.

fined in two main sub processes (Figure 4): the ad-

vertisement of a new actor providing a service and

the procedure of a patient choosing a new service

provider. In the former, the new service should gen-

erate a certificate and ask a Certification Authority to

sign it. Then, the actor (services or healthcare profes-

sionals that want to deposit or access the information)

creates a description of the service, sign and register

it.

When a patient wants to use a new service, he

searches the service, chooses the provider and vali-

dates the CA signature. Then, using the public certifi-

cate of the chosen service, the patient defines the pol-

icy for that actor, controlling what the service/actor

can view or store in his record.

HYBRID ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS

573

Figure 4: HEHR joining new actor.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The HEHR tries to create a true longitudinal patient-

centric electronic health record, based on contribu-

tions from all actors that provide healthcare services

to the patient. This open collaboration, controlled by

the policies specified by the patient, can deal with his

mobility and freedom of choice, since all they can

easily join as patient collaborators. The bureaucratic

sharing problem between actors is solved by the use

of the patient consent. The healthcare professionals

can trust in the clinical integrity, since it’s signature

can check all collaborations integrity.

Considering the features of the EHR and PHR (Ta-

ble 1), the HEHR can be described as a collaborative

record, which guardian is a service acting on the user

behalf. With such kind of record, it is expected the

deposit of more information, combining clinical in-

formation with other health related data, e.g. sport

activity monitoring, athletic training programs, and

other information produced by alternative medicine

procedures. Moreover, new paradigms, such as home

care, remote patient monitoring, and elderly care, can

bring added value to the patient HR.

This paper presented the difficulty that two main

streams of digital health records, EHR and PHR, have

dealing with the challenges of patient mobility, free-

dom of healthcare providers choice, and liberaliza-

tion of market. It also introduces a Hybrid Electronic

Health Record, that empowers the patient with access

control to his medical information, as enabling the ac-

cess to new healthcare services. As a result, it estab-

lishes a longitudinal patient-centered electronic health

record created by the collaboration of all the actors.

We are currently developing a framework to en-

able hybrid records, taking advantage of existing in-

terfaces between EHR and PHR. Further work in-

cludes the implementation of a storage solution and

the evaluation of data formats, such as XML serial-

ization of CDA, CCR and OpenEHR archetypes.

REFERENCES

Chanda, R. (2002). Trade in health services. Bulletin of the

World Health Organization, 80(2):158–63.

Dolin, R., Alschuler, L., Boyer, S., Beebe, C., Behlen, F.,

Biron, P., and Shabo Shvo, A. (2006). Hl7 clinical

document architecture, release 2. Journal of the Amer-

ican Medical Informatics Association, 13(1):30.

EESC (2007). Report on the implementation of the commis-

sion’s action plan for skills and mobility com(2002)

72 final. Technical report, Commission of the Euro-

pean Communities.

Eysenbach, G. (2008). Medicine 2.0: social networking,

collaboration, participation, apomediation, and open-

ness. Journal of medical Internet research, 10(3):e22.

Ferranti, J., Musser, R., Kawamoto, K., and Hammond, W.

(2006). The clinical document architecture and the

continuity of care record. British Medical Journal,

13(3):245.

HIMSS (2010 (accessed July 19, 2010)a). Himss ehr defi-

nition. http://www.himss.org/ASP/topics ehr.asp.

HIMSS (2010 (accessed July 19, 2010)b). Himss phr defi-

nition. http://www.himss.org/ASP/topics phr.asp.

NCRR (2006). Electronic Health Records Overview. Tech-

nical report, MITRE.

OpenEHR (2007). Introducing openehr - revision 1.1. Tech-

nical report, OpenEHR.

Pedrosa, T., Lopes, R., Santos, J., Costa, C., and Oliveira,

J. (2010). Towards an EHR architecture for mobile

citizens. In HealthInf 2010 Proceedings, pages 288–

293, Valencia, Spain.

Santos, J., Pedrosa, T., Costa, C., and Oliveira, J. (2010).

Modelling a portable personal health record. In

HealthInf 2010 Proceedings.

Smith, K. and Kalra, D. (2008). Electronic health records

in complementary and alternative medicine. Interna-

tional journal of medical informatics, 77(9):576–88.

The Lancet (2008). Electronic health records. The Lancet,

371(9630):2058–2058.

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

574