SUPPORTING SAFETY THROUGH SOCIAL TERRITORIAL

NETWORKS

Martin Steinhauser, Andreas C. Sonnenbichler and Andreas Geyer-Schulz

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Kaiserstrasse 12, Karlsruhe, Germany

Keywords:

Safety, Security, Social Networks, Territorial Safety, Secure City, Neighborhood Watch, Informal Social

Control.

Abstract:

Today, crime and fear of crime are related to a loss of social control in large cities. In combination with the

bystander effect, help might not be provided in the case of an emergency. This paper suggests the framework

of a Community Watch Service. The conceptional architecture enables citizens to join virtual, territorial

communities. Citizens can create their own virtual territories. These territories are linked to software services

offering functionality like reporting damage to public property, receiving information from public authorities

or organizing help in the neighborhood. The framework aims to improve social control in a positive way and

increase public safety in large cities. We demonstrate the Community Watch Service as a prototype which is

available for standard web browsers and Android-based mobile phones.

1 INTRODUCTION

Crime in public places unfortunately happens every-

where and often. A 17-year old girl was injured

by another girl in Karlsruhe. The incident was wit-

nessed by several bystanders (KAN06, 2006). In Mu-

nich business man Dominik Brunner was beaten to

death while defending young people against attackers

(Spi07, 2010). Also in Munich senior citizen Bruno

Hubertus was attacked by two young men because he

stared at them (Spi07, 2007). All three cases have in

common that the offenders are young people commit-

ting the crimes due to negligible causes. The attacks

have taken place in large cities with lots of bystanders

around. None of them provided help.

In the article (Ovelgoenne et al., 2010) an online

service is described how to use one’s personal so-

cial network to receive help in an emergency situa-

tion. This Emergency Alert Service (EAS) collects

data from the user’s own contacts and calculates a

friendship network. This network is used in case of an

emergency. By making use of geo-location data of the

victim, friends close enough to provide help and au-

thorities (e.g. police) are alerted through their mobile

phones. The EAS has been designed on a peer-to-peer

mechanism and is based on mobile applications. The

success of the EAS critically depends on the size of

one’s social network, the local proximity of one’s so-

cial groups, and the strength of the social norms lead-

ing to help (social control). Therefore, in this paper

we extend the Emergency Alert Service to a service

bundle of territory-based social services. The motiva-

tion for this is that territory-based social services lead

to an improvement in ‘real-life’ social groups build-

ing in one’s neighborhood and thus improve the social

relations and reinforce a positive social control.

Our service framework integrates territories in so-

cial networks: People register with their home loca-

tion to be able to join local territories. They can also

create territories on their own. These territories and

the services on top are used to pass on ‘territorial’ in-

formation. Different kinds of services are possible:

chat functionality,broken windows or damage to pub-

lic property can be reported to authorities and munic-

ipal administration can contact citizens, up to people

in need that can ask for help.

With our work we aim to integrate and enable cit-

izens to take over (more) responsibility for their place

of living. We hope to create more of a feeling of

ownership and commitment in the neighborhood. To

achieve this, we focus on the power of social net-

works, pervasive computers and internet technology.

In section 2 we motivate our service by giving ba-

sic information when and how people feel secure and

how safety in places, e.g. cities, can be achieved. Sec-

tion 3 reviews current scientific work and applications

in this field. In section 4 we describe our conceptional

architecture for a territorial safety service framework

91

Steinhauser M., Sonnenbichler A. and Geyer-Schulz A..

SUPPORTING SAFETY THROUGH SOCIAL TERRITORIAL NETWORKS.

DOI: 10.5220/0003456800910099

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2011), pages 91-99

ISBN: 978-989-8425-70-6

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

and present it’s implementation as a prototype in sec-

tion 5. We round up this paper in section 6 by a con-

clusion and look out for future work.

2 FUNDAMENTALS AND

CHALLENGES

In 2010 for the first time worldwide more people live

in cities than in the rural area (BPB10, 2010, p. 47).

The consequences of that trend have been analyzed by

Urban 21: the experts’ report on the future of cities

(Hall and Pfeiffer, 2000, p. 205). For mature cities

the report predicts, for example, the proceeding sepa-

ration of rich and poor people in urban areas and in-

creasing conflicts between them. Crimes as a conse-

quence of social tensions due to poverty are regarded

as the classical theory in criminology(Eisner, 1997, p.

39-41). Statistics prove a higher occurrence of crimi-

nality in cities than in rural areas (e.g. (BKA07, 2007,

p. 46)). For the reasons for having an urban-rural gap

in criminality we refer to Oberwittler and Koellisch

(Oberwittler and Koellisch, 2003, p. 135).

Not only is the criminality higher in big cities but

also the fear of crime. Surveys from 1999 (compare

(BKA99, 1999, p. 48) among others) show a remark-

able difference in the categories ‘felt insecurity’ and

‘going to be a victim soon’ depending on the size of

the population (Wurtzbacher, 2008, p. 59). Especially

street crimes like the ones mentioned in section 1 have

a considerable effect on the sense of security, due to a

high number of possibilities to commit a crime on the

one hand and the few chances to avoid such crimes

on the other hand (Koetzsche and Hamacher, 1990, p.

6ff).

According to Boers, the reasons for a higher fear

of crime can be broken down in three categories

(Boers, 1991, p. 45ff): A person fears crime more

after being a victim (victimization perspective), the

fear of crime increases with the loss of informal so-

cial control (social-control perspective), and media,

politics, and official institutions influence the percep-

tion of the security (social-problem perspective). The

theory of the social control perspective is closely re-

lated to the Broken Windows Theory by Wilson and

Kelling (Luedemann and Ohlemacher, 2002, p.144).

Since informal social control plays a major role in

crime as well as in the fear of crime, it is worth to

be investigated more deeply. Fassmann (Fassmann,

2009) describes the differences between urban and ru-

ral areas, also focusing on social relationships. In a

big city it is not possible to know all people by their

names, characteristics and history. The traditional in-

teraction with neighbors through knowing and caring

for them is replaced by anonymous and often chang-

ing contacts to a big circle of acquaintances. Regard-

ing to Simmel (Simmel, 1903, p. 122), townspeo-

ple can’t face others with the same emotionality (par-

ticipating, understanding) and they build up a shield

against many of the stimuli in a city. Townspeople

do not only react differently to their environment, but

they also notice only parts of the reality around them

(e.g. people in need).

The characteristics of people living in a city also

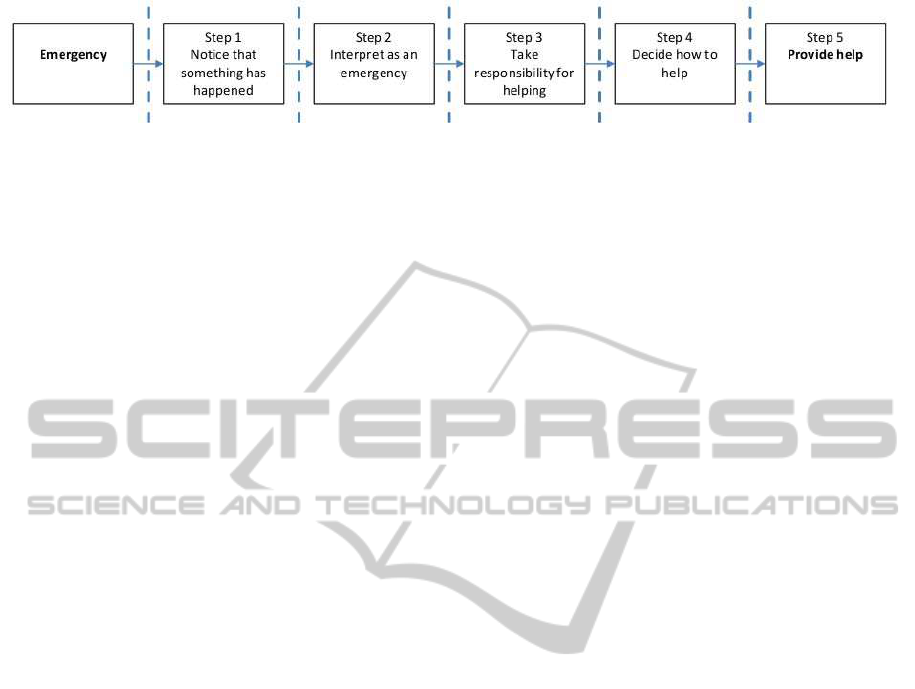

affect the emergency process. Whether citizens are

willing to help people in need depends on a number

of criteria explained by Darley and Latane in the so-

cial help process (see figure 1). For a detailed anal-

ysis, especially focusing on the bystander effect, the

main reason for unhelpful crowds, we refer to (Geyer-

Schulz et al., 2010).

Studies also show that people help more often, if

they know the area. A person, who has fallen down,

gets less help in an airport than at a subway station

(Luedemann and Ohlemacher, 2002, p. 154). We ar-

gue that the criteria ‘known environment’ influences

helpfulness.

One main point of our suggested territory-based

service framework is the aim to strengthen the infor-

mal social control of citizens since this reduces the

fear of crime as well as crime itself.

3 RELATED WORK

This section takes a look at the latest concepts dealing

with crime, participation of citizens and using infor-

mation and communication technologies.

The region of Brandenburg (Germany) offers a

portal offering persons, registered by email, the possi-

bility to report issues to the city administration. Mes-

sages are categorized (waste, vandalism...), contain

a description, a postal address, the possibility to add

pictures and a processing status. The issues can be

tracked by users and employees. Employees of the

city administration update the issues. This leads to

an increased transparency (Mae10, 2007). FixMyS-

treet (http://www.fixmystreet.com) follows a similar

approach.

To inform their citizens about crime, the Los An-

geles Police Department (LAPD) publishes a crime

map. The crime map is part of an E-Policing strategy

which applies the community policing ideas through

the internet. A police district includes several ‘Ba-

sic Car’-districts. Citizens have the possibility to en-

gage as Senior Lead Officer who is the contact per-

son for the local inhabitants. His task is to watch

local criminality and to inform the police and the

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

92

Figure 1: Social Help Process according to Darley and Latane ((Latane and Darley, 1970, p. 152-155) and (Brehm et al.,

2005, p. 367)).

citizens about news (http://www.lapdcrimemaps.org).

German newspapers have started to track the level of

crime on a map, too (see the ‘Blaulichtkurier’ under

http://www.berliner-kurier.de).

Video surveillance has been used for years to pre-

vent crime on streets and public places. Many of

the cities in Great Britain are using the closed cir-

cuit television-technology. A critical point of video

surveillance is the monitoring of recorded videos

(Floeting, 2007, p. 6-7). A concept for an involve-

ment of citizens in monitoring is offered by the com-

pany Internet Eyes Ltd. People all overthe world have

the chance to watch randomly selected surveillance

cameras without knowing their actual location. By re-

porting an incident they gain points and receive prices

(http://interneteyes.co.uk).

The company Innovative Support To Emer-

gencies Diseases and Disasters (InSTEDD)

(http://instedd.org) has published the concept

paper ‘Watchfire’. It deals with emergencies (e.g.

storms, fire, earthquakes and epidemics) in which

inhabitants can’t expect fast help from official aid

organizations, but must rely on help from neighbors

(Beckman and Rasmussen, 2010). As potential

users InSTEDD especially addresses participants of

neighborhood watch organizations. After signing

up a user can see other users and their whereabouts

on a map. Users can chat with each other and can

send messages through mobile phones. Watchfire

can be connected to professional aid organizations,

but is primarily designed as local alert system for

neighbors.

4 THE CONCEPT OF THE

COMMUNITY WATCH

SERVICE

In section 3 we described some ways of dealing with

crime and fear of crime. A recurring element is the

focus on social-control. Social-control is hard to pro-

mote especially in larger anonymous cities. Most of

the existing concepts have territorial aspects included:

Segregation, urban development of territories, neigh-

borhood watch organizations, the police who is re-

sponsible for a district, reporting issues to the local

city administration or a chat functionality to talk to

neighbors. But also concepts like Getting Help In A

Crowd (see (Geyer-Schulz et al., 2010)) which are in-

dependent of setting up a territory are possible. All of

them have in common that there needs to be a moti-

vation why persons participate in crime prevention or

the emergency response process.

The main idea of the concept, named ‘Commu-

nity Watch Service’ (CWS), is to create and improve

relationships between neighbors. We do this by offer-

ing territory-based services in which only residents

can participate. One consequence out of that is to

know and verify the residence of a user. Another is,

to map services to arbitrarily shaped territories. By

this, we aim to strengthen the identification of persons

with ‘their’ territories since only in-territory-people

(in-group) may join. Furthermore, services can be

offered in well-defined territories only, making sure

that only local users can participate. We have to en-

sure privacyof personal data, especially geo-locations

of users. We expect people do not want to see per-

sonal information like their address being public in-

formation. Therefore, we do not show geo-positions

of users but ensure only, that they can join territo-

ries only their place belongs to. Furthermore, we use

pseudonyms.

The creation of a relationship between people of-

ten starts with the fact that they live next to each other.

This closeness can result in the feeling of belonging

together as a group. Living next to each other cre-

ates common interests (e.g. talking about city top-

ics, shared problems with vandalism, traffic related

issues, fear of crime, ...) and opportunities to help

each other (e.g. borrowing milk, receiving parcels,

recommending a restaurant, taking care of children,

...) which could be channeled and supported by in-

formation and communication technology. The hy-

pothesis is: Shared interests, opportunities for mutual

help and the size of one’s social network strengthens

the motivation to engage locally even to the point that

help is provided in the case of an emergency.

We do not restrict territory-based services to

crime-related topics: Results of research on neighbor-

hood watch programs show that services only moti-

vated by crime related issues tend to get inactive over

SUPPORTING SAFETY THROUGH SOCIAL TERRITORIAL NETWORKS

93

Figure 2: Combination of different territories.

time (Garofalo and McLeod, 1989, p. 336). There-

fore, we offer a mixed bundle of services which can

be crime related but need not to. The question which

needs to be answered is, how to enable citizens to

make use of multiple services in an easy way. Right

now there are a lot of services available, offered by

police, city administration or others. The Community

Watch Service must offer its services in an easy, auto-

mated and structured way.

The living situation of a citizen can be very differ-

ent. There are mini-neighborhoods with one-family-

houses and block constructions. People in both

places may have different attitudes and possibilities

to engage in their neighborhood. Therefore, offered

territory-based services may differ as well. E.g. in

a highly anonymous environment, a local chat func-

tionality may be a good starting point. A rescue ser-

vice asking residents for help in the case of an emer-

gency may be futile at first. Nevertheless, an in-

creasing number of people using local services of-

fered through CWS may improve the relevancy (ac-

ceptance) of such an emergency service later: First,

people start with chats, then make use of something

like fixmystreet. Later a network with a Senior Lead

Officer can evolve and then the willingness to partic-

ipate in more demanding services like a local rescue

service may rise. In other words - to reach the aim

of ‘Supporting Safety Through Social Territorial Net-

works’ one must start with non-safety relevant ser-

vices first an can build upon that.

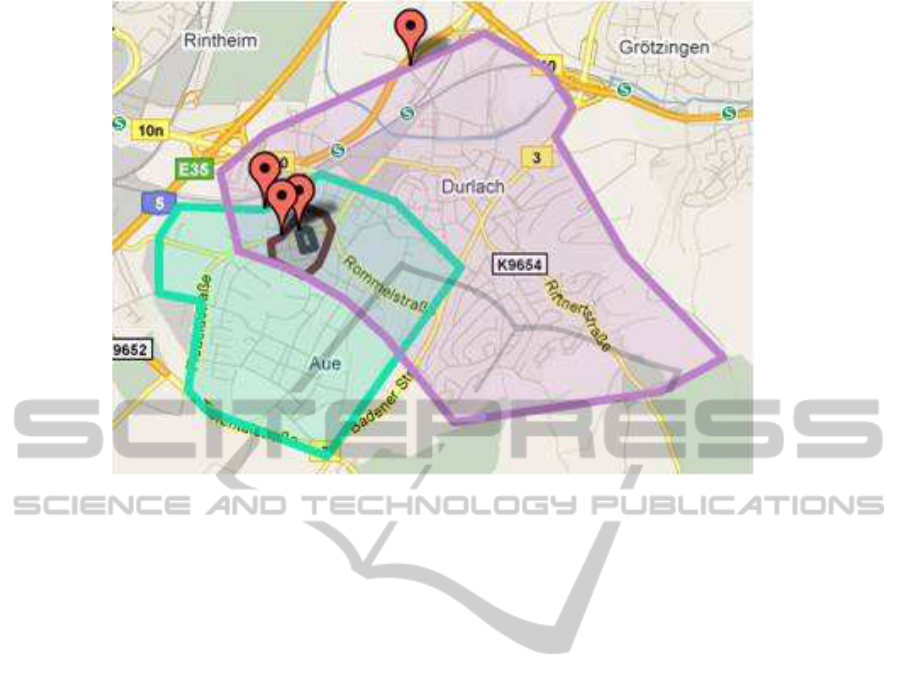

The shape of a territory is determined by the of-

fered service. A fixmystreet-like service territory

needs to be set up according to the administrative area

of the city administration. Reported issues in territo-

ries are forwarded to the responsible employee by the

service. The size and shape of territories may fol-

low ‘official’ boundaries like city limits, districts, 911

service areas, or can be defined freely by the users’

needs. For architectural reasons for territory shap-

ing, we refer also to the book of Christopher Alexan-

der (Alexander, 1979). In any case the owner of the

territory has the power to shape it. To simplify the

shaping of territories, the company Urban Mapping

Inc. offers official boundaries which may then be ap-

plied (http://www.urbanmapping.com). They can be

used as orientation for owners of territories in order

to shape them. Figure 2 shows an example from the

prototype described in section 5.

A resident (whose actual location is hidden for

data protection reasons) is the owner of the grey, in-

ner most small circle territory. It is linked to a emer-

gency response service wherein the user participates

as emergency helper (the latter information is not de-

picted in the figure). The same person is registered

in the territory ‘Neighbors and friends’ (brown, small

circle) and ‘fixmystreet’ (turquoise, large on the left).

There is another territory for which he is not regis-

tered (purple, large territory on the right). Detailed

information about territories, linked services, owner,

subscription state and so, on pops up when moving

the mouse over the territory marker (see figure 3).

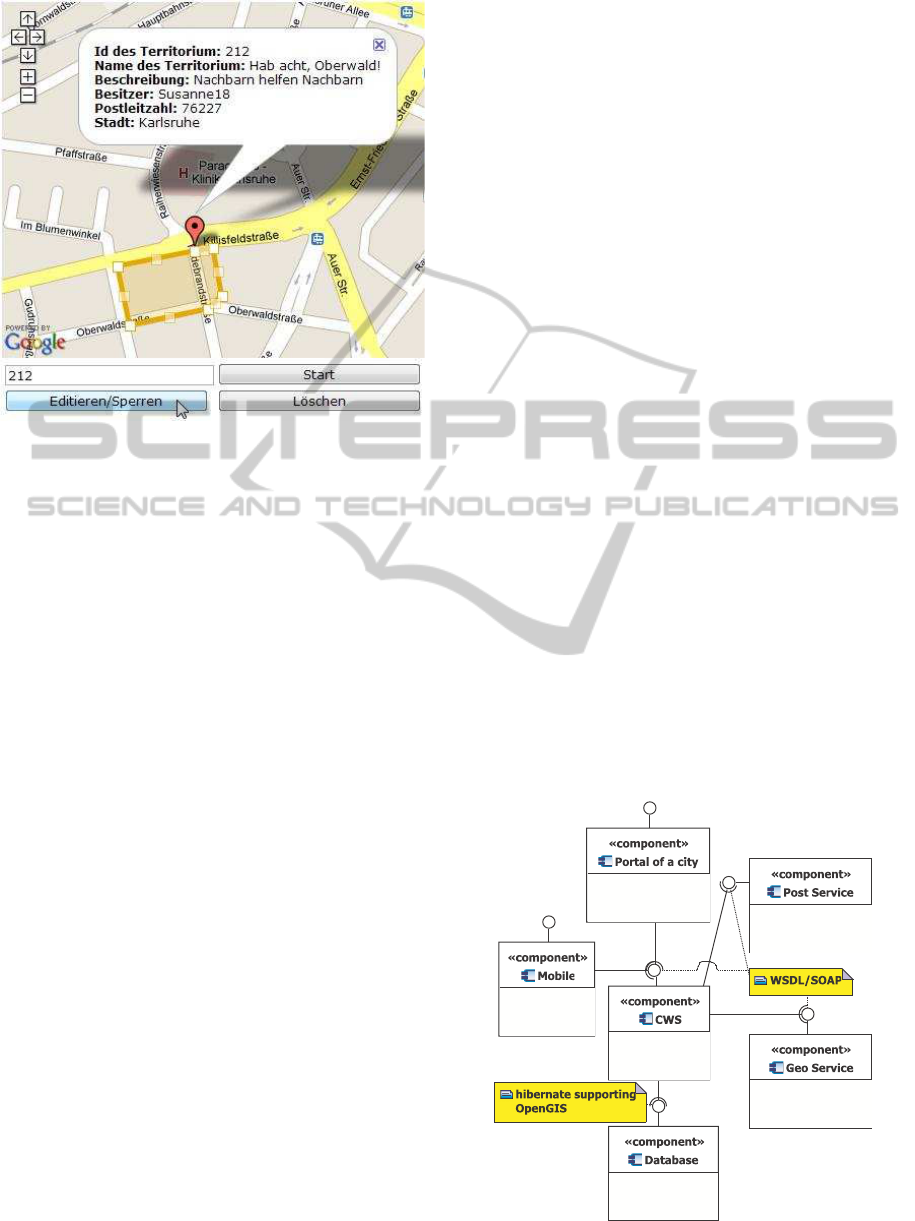

Generally, a user can create his own territories and

link them to services. Furthermore, a user can sign up

to existing services covering his registered place of

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

94

Figure 3: Edit of territories.

living. The sign-up process may include the approval

of the territory owner. The CWS framework supports

general functions. These include among others the

registration of a new user with checking his residence,

creating and editing territories and linking them to

services, searching for them and editing user settings.

The service itself might be offered by third parties. A

territory is always linked to exactly one service. Oth-

erwise, users registered for a service would have to

sign-up for new services attached to the same terri-

tory again. Nevertheless, the shape of a territory can

be (technically) reused for another territory (with the

same shape) but linked to another service. The idea is

to have encapsulated services with a given set of func-

tionalities. Groenroos conceptional augmented ser-

vice models can be applied to differentiate core ser-

vices (Groenroos, 2007, p.163ff). ‘Small and simi-

lar’ functionalities can extend an existing core service

(attached to a territory) but (different) new core func-

tionalities would lead to a new service.

We expect CWS being successful only if valuable

services are provided for territories. Therefore, the

following paragraph is dedicated to give some exam-

ples of territorial services. The order of examples re-

flects the degree of commitment or participation level

of the citizens. Services with a lower requirement

level are listed first.

• Information Service of the City.

The city informs selective territories about

planned construction sites, street festivals, cul-

tural events, ...

• Information Service of the Police.

The police provide general information about

crime in the territory, crime prevention activities,

and specific information on crime prosecution.

Police publishes mug shots in the newspaper or

on the police’s homepage. Those mug shots can

be published promptly and selectively even on the

mobile if offered.

• Chat Functionality.

People talk to people nearby about neighborhood

gossip (weather, found a cat), but can also talk

about security relevant stuff: an open car in front

of the house, persons loitering in front of the

house.

• Fixmystreet Similar Service.

Either the city administration offers this service

and deals with issues (CustomerToAdministra-

tion) or people in the neighborhood take care

themselves (CustomerToCustomer).

• Local Emergency Helper.

In the field of medical emergencies there are al-

ready first responder concepts in place in which

people agree to do locally voluntary work. The

German red cross association has built up lo-

cal first responder teams to bridge the gap un-

til professional help of aid organizations arrives.

Those teams are integrated in the rescue chain and

get informed by the headquarter (Schoechlin and

Ayasse, 2004, p. 1). The local emergency helper

is a service where the helper is registered for a ter-

ritory and others using this service push a button

on their mobile which locates themselves and in-

forms helpers registered in the callers territory.

In addition to these more security related services

the CWS framework offers the freedom to be ex-

Figure 4: Architecture of the CWS prototype.

SUPPORTING SAFETY THROUGH SOCIAL TERRITORIAL NETWORKS

95

Figure 5: BPMN process of a CWS user registration.

tended with other applications. A lot of room for cre-

ativity: a territory for finding people to go out with,

organizing a street festival, offering mutual help, or

other services which improve social interactions in

the neighborhood are possible.

From these requirements it follows that peo-

ple may want to be informed about new territo-

ries/services in their environment. Nevertheless, to

much information would possibly be reflected as

spam. To deal with excessive generation of territories

the territory creation and user perspective must be an-

alyzed. One solution is to collect notifications of new

territories and send out personalized newsletters one’s

a month.

5 PROTOTYPE

Our CWS prototype includes the basic functions of

the described concepts. This includes registering for

CWS, creating and editing territories, finding terri-

tories and joining them. The prototype is currently

available for standard personal computers through a

web browser and also for mobile phones based on An-

droid (http://www.android.com).

To make use of (backend) services already avail-

able, we used a web service technology for our im-

plementation. Pautasso et al. (Pautasso et al., 2008)

discuss the difference between big web service (WS-

*) and REST. Their result is, that REST needs less

architectural decisions to make but ‘lead[s] to signif-

icant development efforts and technical risk, for ex-

ample the design of the exact specification of the re-

sources and their URI addressing scheme’ (Pautasso

et al., 2008, p. 813). Since CWS wants to be an open

framework for services with territorial aspects, for an

encapsulated application the full complexity of WS-*

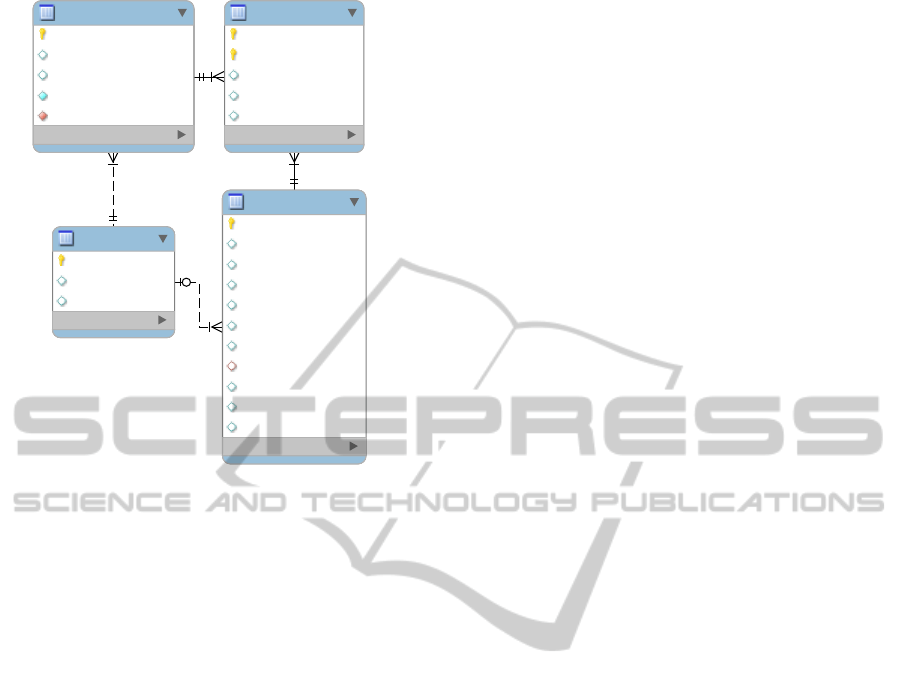

services can be used. Figure 4 shows the components

and their connections, the communication interfaces

and protocols of the chosen architecture. The main

intention of the figure is to give an overview of the

needed components. The components can be related

to the lanes of the process description in figure 5 - the

sub processes in the lane ‘User’ are implemented by

‘Mobile’ and ‘Portal of a city’.

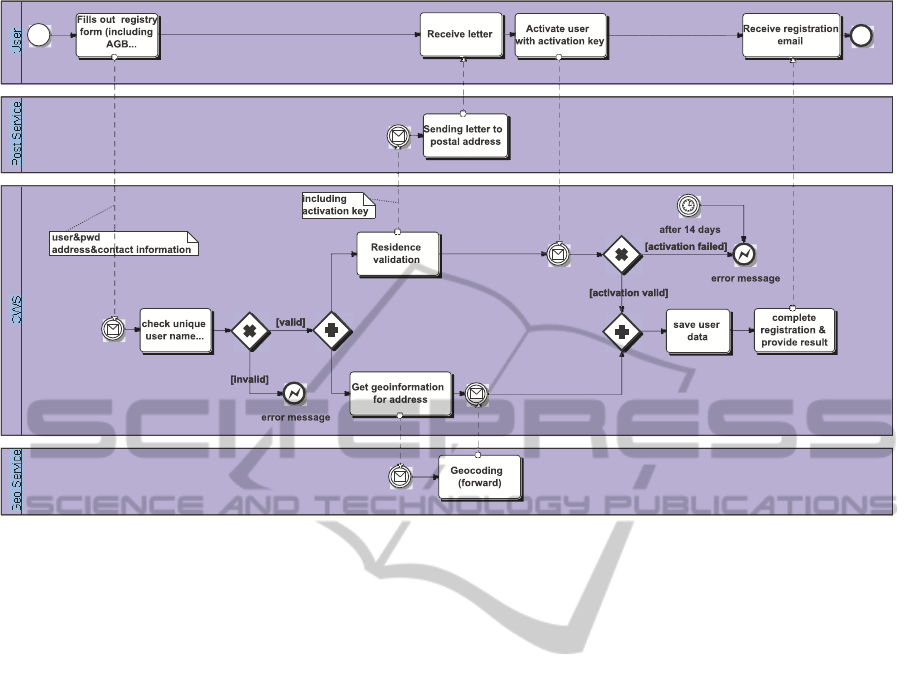

A key issue in the CWS concept is the residence

of a user. This location is verified during the sign-

up process of a user. This can be done by trusted

third parties like the city administration who main-

tain the city register listing all residents. If trusted

third parties lack an API or the permission to access

these kind of data, a validation process as used e.g. by

credit card companies can be applied. The CWS pro-

totype integrates the services offered by ‘Postal Meth-

ods’ (http://www.postalmethods.com) to send letters

to an address of a user. The letter contains an acti-

vation key which secures that the user really lives at

the specified address. Only after activation, the user

registration process for territories is finished success-

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

96

!

"""

""

#!$%&'%

(

#

$%&'%

#""

)

Figure 6: Entity Relation diagram of the CWS prototype.

fully.

To be able to do calculations with the address of a

user, the address is translated to spatial data for which

the geo-referencing service of Via Michelin service

is used (http://www.ViaMichelin.com). Of course the

user data and especially the location must be stored

on a database level. Since later on there will be fre-

quently requests for users of a territory, spatial data

is directly saved in the OpenGIS format to be able to

perform this request on the database level.

Figure 5 shows the different steps that are exe-

cuted during user registration as a BPMN diagram

(SOAP messages are shown as a postal symbol). Af-

ter a successful activation, the user can create, edit

and delete own territories by using map functional-

ity. Google Maps (http://maps.google.com) offers the

Google Maps API. The API allows creating polygons

in all desired shapes. Such polygons consist of mul-

tiple geographic points which are transferred to the

CWS. The CWS saves the territory and the corre-

sponding user data in its database.

Furthermore, a user can search for territories and

is notified by email if new territories are created ‘on

top of’ him. The territory search makes use of the hi-

bernate criteria technology to efficiently execute com-

plex searches (combination of multiple search criteria

over many databases). By doing so, an user can ex-

plore different parts of the city and their social co-

hesion. Territories can be assigned properties like

‘isHidden’ to allow citizens to exclude their territory

and the linked service from public view. This feature

may be used e.g. in the service ‘senior citizen part-

nership’ which would otherwise give criminals easy

targets.

The search function supports owner-related,

location-related and service-related attributes. When

a new territory is created, users with their residence

inside this territory are identified. If these users

have activated email notification, they are informed

by email to explore the new territory. Figure 6 shows

how the underlyingER-diagram looks like to store the

necessary data. A user may also join existing territo-

ries. He can only join, if the territory related to the

service includes the user’s residence.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Public crime and fear of crime is common in larger

cities. In section 2 we have presented some funda-

mentals, how a low level of social control correlates

with the size of the population. Besides other aspects,

this is an important factor in crime and felt crime

level. Furthermore, the bystander effect may prevent

help in the case of emergencies.

To strengthen social control we suggest the Com-

munity Watch Service (CWS) Framework. The ser-

vice framework enables citizens to form territorial

communities. Every participant in the CWS can join

communities related to his place or create own terri-

tories. Such a community is linked with certain func-

tionality. For example, in one community, informa-

tion about planned construction sites is distributed to

the participants by the city administration. Another

community service deals with damage to public prop-

erty: Citizens report damage while employees of the

city administration track these issues and fix them. A

third possibility is local emergency helpers, who re-

spond to help requests.

In this article we described the conceptional archi-

tecture of the Community Watch Service and its real-

ization as a first prototype. A full implementation of

this service and a field test remain for future work.

Even without a full CWS system in the field, user

surveys can give a first indication of how a concrete

territorial service bundle should look like. First ac-

ceptance tests with residents could be conducted with

mockups of the user interface.

The mobile aspect of CWS hasn’t been discussed

in this paper that much but holds a significant poten-

tial. There are many appliances thinkable. A very

sophisticated way of integration CWS in a mobile ap-

plication (next to just locate yourself and show the

map on the Android-based mobile phone) is shown in

figure 7.

SUPPORTING SAFETY THROUGH SOCIAL TERRITORIAL NETWORKS

97

Figure 7: Augmented reality in combination with territorial services.

The user sees through a camera display the real

world with a digital overlay of territories above him

- he might feel safer since he is walking through the

supervised neighborhood ‘NW-Block 17’.

With regard to existing social networks, like e.g.

Facebook, the CWS concentrates on real social rela-

tions: the identity and the residential address of per-

sons participating in the CWS are validated. Only lo-

cals are allowed to participate in territories. The as-

pects of belonging together present in local neighbor-

hoods, local commitment and informal social control

are strengthened.

From a technological point of view, CWS is an

open framework (available for standard web browsers

and Android based mobile phones) which is using dif-

ferent existing web-services. CWS and all the web-

services employed rely on flexible rights management

services which handle location and group-based ac-

cess requests. Today, none of the existing commercial

social networks provides this functionality. The in-

dependence of an existing commercialised social net-

work with given APIs leaves the freedom of devel-

opment completely new functionalities like searching

for new services/territories nearby. Yet, CWS could

be coupled with or added to the existing function-

ality of a social network - provided the rights man-

agement services of the social network are flexible

enough and extended with territorial functionality -

because in the end - the people that are assigned to

local territories, connected with each other indirectly,

are potential customers of a social network.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research leading to these results has received

funding from the European Community’s 7th Frame-

work Program FP7/2007-2013 under grant agreement

n

◦

215453 – WeKnowIt.

REFERENCES

Alexander, C., 1979. The Timeless Way of Building, vol-

ume 1 of Center for Environmental Structure Series.

Oxford University Press, New York.

Beckman, L. and Rasmussen, E., 2010. WATCH-

FIRE: Neighborhood Watch 2.0. In-

STEDD, http://www.cmu.edu/silicon-valley/dmi/

workshop/position-paper/beckman-pp.pdf, last

accessed: 2010-08-19.

BKA07, 2007. Polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik 2007.

Bundeskriminalamt, http://www.bka.de/pks/

pks2007/download/pks-jb_2007_bka.pdf, last ac-

cessed: 2010-07-12.

BKA99, 1999. Polizeiliche Kriminal-

statistik 1999. Bundeskriminalamt,

http://www.bka.de/pks/pks1999/docs.zip, last ac-

cessed: 2010-07-12.

Boers, K., 1991. Kriminalitaetsfurcht: ueber den Entste-

hungszusammenhang und die Folgen eines sozialen

Problems, volume 12 of Hamburger Studien zur Krim-

inologie. Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg.

BPB10, 2010. Verstaedterung: Stadt- und Land-

bevoelkerung in absoluten Zahlen und in Prozent der

Weltbevoelkerung. Bundeszentrale fuer politische

Bildung, http://www.bpb.de/files/HBW2V2.pdf, last

accessed: 2010-07-02.

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

98

Brehm, S. S., Kassin, S. M., and Fein, S., 2005. Social psy-

chology. Houghton Mifflin, New York, 6. aufl. edition.

Eisner, M., 1997. Das Ende der zivilisierten Stadt? Die

Auswirkungen von Modernisierung und urbaner Krise

auf Gewaltdelinquenz. Campus-Verl., Frankfurt, New

York.

Fassmann, H., 2009. Stadtgeographie, volume 1 of Allge-

meine Stadtgeographie. Westermann, Braunschweig,

2. neubearbeitete aufl. edition.

Floeting, H., 2007. Can Technology Keep Us Safe? New

Security Systems, Technological-Organizational Con-

vergence, Developing Urban Security Regimes.

Garofalo, J. and McLeod, M., 1989. The structure and oper-

ations of neighborhood watch programs in the United

States. Crime & Delinquency, 35(3):326.

Geyer-Schulz, A., Ovelgoenne, M., and Sonnenbichler, A.,

2010. Getting help in a crowd – a social emergency

alert service. In Proceedings of the International Con-

ference on e-Business, Athens, Greece. INSTICC.

Groenroos, C., 2007. Service management and marketing:

customer management in service competition. Wiley,

Chichester, 3. ed. edition.

Hall, P. and Pfeiffer, U., 2000. Urban 21: der Experten-

bericht zur Zukunft der Staedte. Menschen, Medien,

Maerkte. Dt. Verl.-Anst., Stuttgart.

KAN06, 2006. Durch Messerstiche ver-

letzt. KA-News GmbH, http://www.ka-

news.de/region/karlsruhe/Durch-Messerstiche-

verletzt;art6066,50552?show=tfr200661-1352K, last

accessed: 2010-06-29.

Koetzsche, H. and Hamacher, H.-W. (1990). Lehr- und Stu-

dienbriefe Kriminalistik, volume 8 of Kriminalistik.

Verlage Deutsche Polizeiliteratur, Hilden.

Latane, B. and Darley, J., 1970. The unresponsive by-

stander. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York.

Luedemann, C. and Ohlemacher, T., 2002. Soziologie der

Kriminalitaet: Theoretische und empirische Perspek-

tiven. Grundlagentexte der Soziologie. Juventa, Wein-

heim, Muenchen.

Mae10, 2007. 10. eGovernment-Wettbewerb:

Buerger machen mit, Maerker Branden-

burg. Ministerium des Innern des Lan-

des Brandenburg, http://www.egovernment-

wettbewerb.de/praesentationen/2010/maerker_-

online.pdf, last accessed: 2010-08-19.

Oberwittler, D. and Koellisch, T., 2003. Jugendkriminal-

itaet in Stadt und Land. In Raithel, J. and Mansel,

J., editors, Kriminalitaet und Gewalt im Jugendal-

ter: Hell- und Dunkelfeldbefunde im Vergleich, pages

135–161. Juventa, Weinheim, Muenchen.

Ovelgoenne, M., Sonnenbichler, A., and Geyer-Schulz, A.,

2010. Social emergency alert service - a Location-

Based Privacy-Aware personal safety service. In Pro-

ceedings of the 2010 Fourth International Conference

on NextGeneration Mobile Applications, Services and

Technologies (NGMAST), pages 84–89.

Pautasso, C., Zimmermann, O., and Leymann, F., 2008.

Restful web services vs. ‘big’ web services: making

the right architectural decision. In WWW ’08: Pro-

ceeding of the 17th international conference on World

Wide Web, pages 805–814, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

Schoechlin, J. and Ayasse, F., 2004. 10 Jahre First-

Responder-Teams : Erfahrungen beim DRK Mörsch.

Rettungsdienst, 27:230–237.

Simmel, G., 1903. Die Grossstaedte und das Geistesleben.

Zahn & Jaensch.

Spi07, 2007. Was labert der mich an. Spiegel On-

line GmbH, http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/

justiz/0,1518,-525153,00.html, last accessed: 2010-

06-29.

Spi07, 2010. Protokoll einer Eskalation. Spiegel

Online GmbH, http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-

68785414.html, last accessed: 2010-07-12.

Wurtzbacher, J., 2008. Urbane Sicherheit und Partizipa-

tion: Stellenwert und Funktion buergerschaftlicher

Beteiligung an kommunaler Kriminalpraevention. VS

Verlag fuer Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden.

SUPPORTING SAFETY THROUGH SOCIAL TERRITORIAL NETWORKS

99