THE FEASIBILITY OF UBIQUITOUS COMPUTING IN SCHOOL

Longitudinal Study in 1:1 Classes Suggests — Time Matters

Spektor-Levy Ornit, Keren Menashe and Doron Esty

School of Education, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

Keywords: One-to-one, ICT, Ubiquitous computing, Learning environment, Visualization, Information literacy.

Abstract: Despite the growing interest in and excitement about ubiquitous computing in school and 1:1 models, there

is a lack of research that focuses on teaching and learning in these intensive computing learning

environments. This is a particularly salient issue in light of the high cost of implementing and maintaining

1:1 settings. This study evaluates an innovative educational program, taking place in three elementary

schools and one middle school. 1,257 students and their teachers were provided with personal laptop

computers for class and home use. This paper presents a portion of the results concluding four years of

study and focuses on the way science teachers perceive the impact of teaching and learning in ubiquitous

computing environment. Results suggest that "time matters". The statistical analysis as well as interviews

with teachers revealed that as time passes, and the 1:1 settings become a routine in school, it is easier to

detect the advantages of teaching and learning with personal laptops. Students feel more motivated,

experience higher self-efficacy and develop increased technology proficiency for learning. These findings

add unique and positive evidence to the growing body of research regarding one-to-one models.

1 INTRODUCTION

During the last decades, educators and policy-

makers called to move education beyond the

traditional learning environment. Reforms in

education have taken place in many countries. These

reforms formulated new standards and reflect the

overall goal of preparing students for the

requirements of the twenty-first century knowledge

society. Educators are required to redefine

educational goals and integrate technology into the

school curriculum. The integration of technology

within schools has varied: from desktop computers,

to laptop computers (1:1); from computer use in a

specific lesson, to computer use anytime anywhere

(24/7); etc. A one-to-one learning environment is

more than a ratio of one laptop per student; it is the

anytime, anywhere accessibility of resources and

tools; it is a profound involvement and engagement

in the educational process (La Mar, 2005). This

study describes an innovative educational project

that started in 2006 in Israel, taking place in four

schools (three elementary schools and one middle

school) of two small urban communities (grades five

– nine). All students and all teachers were provided

with personal laptop computers for class and home

use. The teaching and learning routinely took place

in an information and communication technology

(ICT) saturated environment and Virtual Learning

Campus (VLC).

However, providing computers are the bare

minimum, since in this age of information,

knowledge is the main resource (Van Weert, 2006).

It is also not enough to simply acquire retrieval skills

in order to gain an advantage over others. The key to

success is using higher-order thinking and learning

skills that will enable implementation of knowledge

at the right time, and recognizing such opportunities

(Salomon & Perkins, 1998).

Society must learn to utilize technology for its

own needs, while placing the citizen at the focal

point (Postman, 1998). It has to take responsibility

for the individual’s general intellectual development,

as well as the abilities and skills to process

information, to calculate, to design, to solve

complex problems, to invent, and to improve one’s

own ability to think (Salomon, 2000, Weston &

Bain, 2010).

2 BACKGROUND

Nowadays, there is a dramatic surge surrounding the

491

Ornit S., Menashe K. and Esty D..

THE FEASIBILITY OF UBIQUITOUS COMPUTING IN SCHOOL - Longitudinal Study in 1:1 Classes Suggests — Time Matters.

DOI: 10.5220/0003482104910497

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education (UeL-2011), pages 491-497

ISBN: 978-989-8425-50-8

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

world of initiatives that provide laptop computers for

students and teachers, aimed at reaching the

pervasiveness of computers in schools. Early

research and evaluation studies suggest several

positive outcomes from one-to-one (1:1) laptop

initiatives, including: increased student engagement

(Cromwell, 1999; MEPRI, 2003; Rockman, 1998),

decreased disciplinary problems (Baldwin, 1999;

MEPRI, 2003), increased use of computers for

writing, analysis and research (Baldwin, 1999;

Cromwell, 1999; Guignon, 1998; Russell, Bebell, &

Higgins, 2004), and a movement towards student-

centered classrooms (Rockman, 1998).

Baldwin (1999) also documented effects on

student behavior at home—more time spent on

homework. Gulek and Demirtas (2005) compared

test scores among students participating and not

participating in a voluntary one-to-one laptop

program in middle school. A significant difference

in test scores was found, in favor of students

participating in the laptop program.

Despite the growing interest in and excitement

about 1:1 computing, there is a lack of sufficient,

sustained, large-scale research and evaluation that

focuses on teaching and learning in these intensive

computing environments (Bebell, & Kay, 2010).

Specifically, there is a lack of evidence that connects

the use of technology in these 1:1 settings with

measuring student achievement. This is a

particularly salient issue in light of the high cost of

implementing and maintaining 1:1 laptop initiatives

and the current climate of educational policy

(Bebell, & Kay, 2010).

Lei & Zhao (2008) contend that when it comes to

the question of what really happens when every

child has a laptop and how the laptops are being

used in classrooms, current studies provide only

general information on “what” is used, “how much”

is used, and the changes in “what” and “how much,”

but not much information on “how” the laptops are

being used in teaching and learning practices (Lei &

Zhao, 2008). Due to the expansion of such initiatives

in many countries, it is required to question the

effectiveness of such learning environments

(Kozma, 2003; Penuel, 2006), to characterize the

one-to-one learning environments and to analyze the

impact of such environments on student

achievements and other variables (Beresford-Hill,

2000; Inan, & Lowther, 2010).

3 RATIONALE

This study evaluates an innovative educational

project that started in Israel in 2006, taking place in

four schools: three elementary schools and one

middle school, in two small urban communities (i.e.,

covering the fifth to ninth grades). All students and

teachers were provided with personal laptop

computers for class and home use. The teaching and

learning has been routinely taking place in an ICT

saturated environment and a Virtual Learning

Campus (VLC). This paper presents a portion of the

results concluding four years of study and focuses

on the way science teachers perceive the impact of

teaching and learning in 1:1 classes. The following

research questions were addressed:

1. What variables can indicate a positive and

significant change in the way students learn in

a ubiquitous computing learning environment?

2. What perceptions and concerns do teachers

hold regarding ubiquitous computing?

4 METHODOLOGY

4.1. Research Sample

This paper presents a longitudinal study. Data was

collected over four years. As mentioned above, the

study took place in four schools: three elementary

schools (one of which includes both elementary and

middle schools) and one middle school, in two small

urban communities. Participants included 1,257

students in the fifth to ninth grades, and 30 teachers

of whom 10 were interviewed intensively.

4.2. Research tools

Research data was collected by means of mixed

methods. Qualitative methods included: classroom

observations, interviews, analysis of the virtual

learning environments, and student outcomes.

Quantitative methods included pre- and post-

questionnaires. This paper presents some of the

findings following this longitudinal study.

5 RESULTS

5.1. Variables Indicating Change in the

Way Students Learn

Data was gathered during four years of research.

However, evidence of improved learning

achievements was hard to identify. Therefore, the

objective was to discover what variables could

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

492

indicate a positive and significant change in the way

students learn in a 1:1 learning environment. The

issues of whether variables of time and age have any

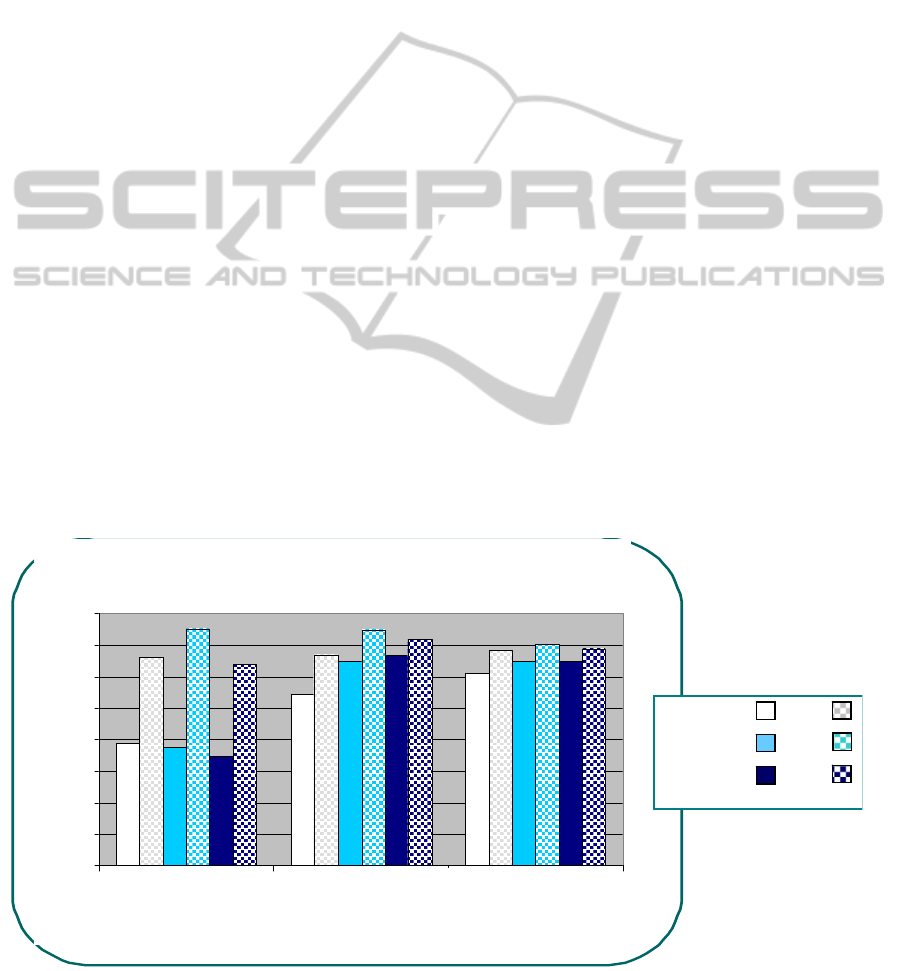

impact were examined. Figure 1 represents data

gathered from all participants in the study

(N=1,257), before and after the first year of learning

with personal laptops. Findings show significant

change in habits of computer usability for learning at

school and at home and most importantly, students’

feelings of higher self-efficacy regarding the use of

technology for learning. These findings were

consistent for all grade levels in all years—during

the individual's first year of personal laptop use

(Figure 1).

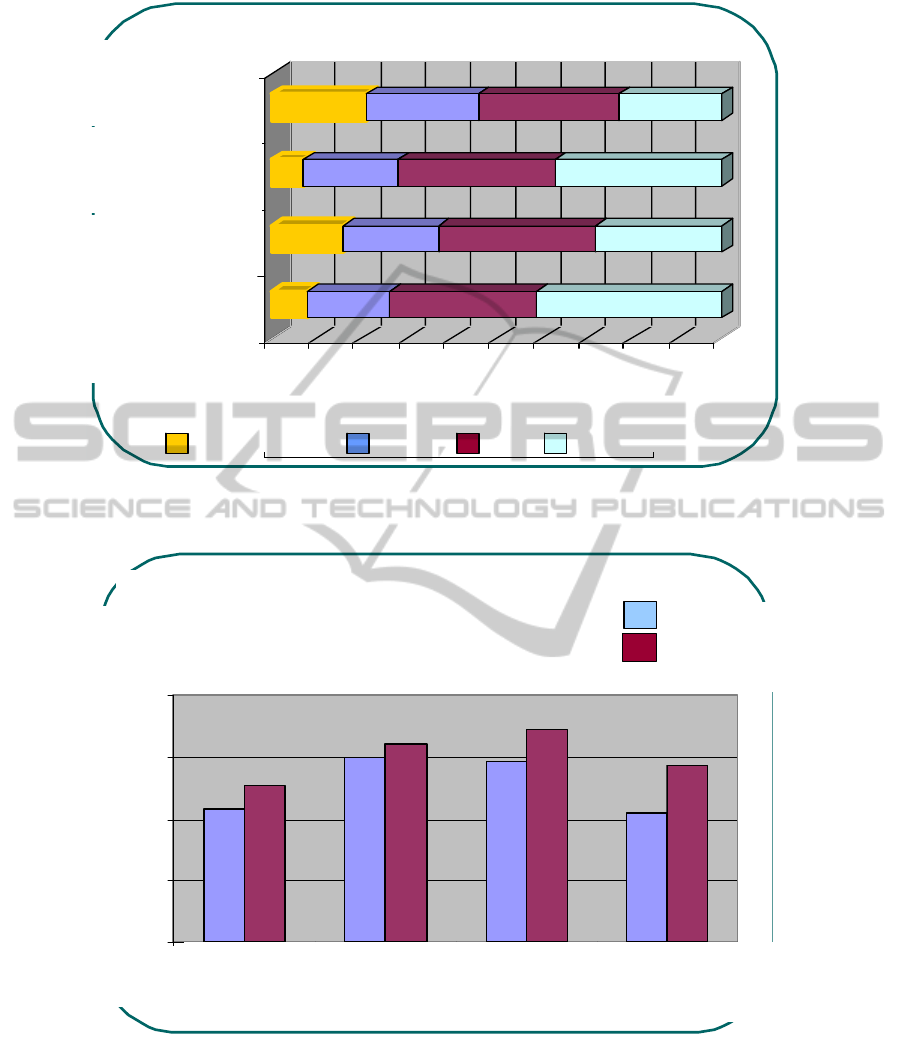

One of the most universal findings in the current

study was that both the implementation and

outcomes of the program were somewhat varied

across the four schools and over the three years of

the student laptop implementation. However, there

was supporting evidence that students' information

literacy and learning abilities were enhanced and

improved (Figure 2). 63% of the students believed

that the laptops enabled them to be more organized

in their studies. 80% of students believed they

gained an improved ability to locate necessary

information and to differentiate between reliable and

unreliable information. 72% of students indicated

they wrote more drafts when preparing their

assignments (Figure 2).

Findings indicated engagement with and

persistence on assignments—even at home. During

interviews, students listed the advantages of the

laptop: Equal access to information: "It’s much more

pleasant to learn with laptops because they give a

sense of fairness—for example, personal opinions

can be expressed…everybody has the same sources

of information…the same access to information…the

same resources. It’s more fun to learn this way—

much faster".

Added interest in lessons: “When I studied with a

book—the book was full of facts. I wrote what was

written in the book and answered according to what

the teacher said. Now that I have my laptop, I’m

exposed to all kinds of reports and scientific

investigations—which might be different from what’s

written in the book. It’s much more interesting and

more up-to-date!"

Improvement in achievements: "Yes, it is a fact. I

get better grades—higher achievements—because I

have more time to think" (T., student with a learning

disability).

Classroom observations revealed that the laptops

also served as a tool for writing and personal

expression. Students used the laptops to work on

their assignments, compose essays, write stories and

prepare presentations. For many students, writing on

computers was easier than using pencil and paper

because they found they could easily rewrite and

edit their work, incorporate images into the text,

insert hyperlinks to make their work interactive, and

improve the design of their final products.

During the initial two years of the personal

laptop computer program, qualitative and

quantitative results showed diverse tendencies, or no

change, regarding motivation for learning. However,

during the third year of the program, when

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

ס"

Frequency of computers

use for learning at school

F requency o f computers

use for learning at home

S elf-efficacy

regarding the use of ICT

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

N = 1,257

*p<0.05, ***p<0.001

Mean level

of agreement

Grade5:PrePost

Grade6:PrePost

Figure 1: Students' mean level of agreement (on a scale of 1-6) regarding the use of laptops, according to age/grade levels,

after first year of learning with laptops.

THE FEASIBILITY OF UBIQUITOUS COMPUTING IN SCHOOL - Longitudinal Study in 1:1 Classes Suggests — Time

Matters

493

8% 18% 33% 41%

16% 21% 35% 28%

7% 21% 35% 37 %

21% 25% 31% 23%

0% 1 0% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100 %

המכסהה תד ימ זוחא

יל רזוע דיינ בשחמב שומי ש

יתא צ מש עדימה תא ןגראל

רשפאמ דיינ בשחמב שומיש

הד ימלב ןגרואמ רת וי תויהל יל

רשפאמ דיינ בשחמב שו מ י ש

ןקתלו תוטויט רת וי בותכל יל

יל ש תודובעה תא

יל רשפאמ בשחמב שומי ש ה

ילש הד ימ ל ה לע הטיל ש רת ו י

םיכסמ אל םיכ ס מ תצ ק םיכסמ םי כ סמ דו אמ

Knowledge management Knowledge management

N=218

Strongly Disagree Disagree Agree Strongly Agree

Percent

I have better

control of my

studies with the

laptop

With the laptop I

write more drafts

when I prepare my

tas ks

The laptop

enables me to be

more organized

in my studies

The laptop enables

me to organize

information I

locate

Figure 2: Students' level of agreement regarding the contribution of laptops to knowledge management after the first year of

learning with laptops. Distribution of responses according to percentage.

*

*

*

*

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

?????? ?????????? ??????? ??? ??????? ?? ? ? ? ? ? ? ???? ?? ???? ??????

??????

Mean level of agreement

Series1

Series2

Intrinsic Extrinsic Task Control of

Orientation Orientation Value Learning Beliefs

N=116

*p<0.05

*

*

*

*

2009 PRE

2009 POST

MotivationMotivation

Figure 3: Students' mean level of agreement with items that expressed different aspects of motivation, before and after the

first year of learning with laptops, during the third year of the program.

examining student motivation of fifth-graders who

joined the program for their first year, a significant

change could be detected for the first time—those

students expressed a significantly higher level of

motivation for learning, as presented in Figure 3.

This is probably due to the fact that the fifth-grade

students could see how elder students learned with

laptops. They were already studying in an

environment that encouraged and implemented

powerful use of technology long before they even

started to learn with personal laptops. Thus, when

those students joined the program and studied with

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

494

their own laptops in 1:1 classes—they were better

prepared and their motivation was enhanced with

less frustration and disappointment.

5.2 Teachers' Perceptions and

Concerns Regarding the

Ubiquitous Computing

Environment

Data from teachers was gathered mainly through

interviews and observations. In the following section

we present some quotes from the interviews.

An interview with one of the science teachers

supports the above findings: Although we learned

about ionic compounds in the laboratory, students

showed greater understanding when they viewed a

computerized simulation. I asked them to prepare

PowerPoint presentations or animations and to

discuss their products during a class discussion. For

many students, only after studying the different

representations on the computer, did they

understand this complex topic. What I explained in

class was not useful in comparison with what they

learned from the different visualizations...I felt a

sense of satisfaction—there are other ways for them

to attain an understanding. Students also gained a

lot of pleasure and were proud of their products,

had intelligent discussions and learned from the

mistakes of other students. They even evaluated their

computer skills and whether the use of the different

computer programs was appropriate…"

Teaching Methods and the Teacher’s Role:

Teacher F: "The teacher is transformed from an

authority of knowledge to a facilitator and an

instructor, and this is something I’ve always

believed in.”

Teacher I: "My job as a teacher has changed a

lot. If at one time it was to transfer knowledge, today

it’s not like that; I’ve added the aspect of facilitator

and I really feel like one. The whole format of

instruction has changed.”

Teacher A: “In traditional learning, you teach a

subject such as leadership and explain about a

leader like David Ben Gurion with the help of a nice

book. Here, when I could show a DVD of David Ben

Gurion giving a speech, I felt the excitement in the

classroom. An extraordinary hush…I felt as if they

were right there at the occasion of the Declaration

of Independence. Hearing Martin Luther King’s

speech and watching him will really leave a lasting

impression on them.”

Workload:

Teacher F: "I never realized how much hard work I

would have, and I’m sure that the work is even

harder for those who don’t have technical skills,

who have to deal with the technical skills as well as

the pedagogical skills that we need to integrate

computers. You need to be sensible about the

proportions and what to use it for.”

Teacher A: “For me personally, as a teacher, a

day when the computer and regular teaching are

integrated is a more varied day— the time passes

more quickly.”

Teacher D: “It’s true— preparing good,

challenging learning materials that make the most of

the endless of possibilities that the laptop uncorks—

demanded a lot of work hours from me.”

Meeting Student Diversity:

Teacher A: “It’s likely that during a certain lesson

I’ll take a group of weaker students and give them a

particular e-learning task, and then give a different

e-learning task to the stronger ones. It doesn’t have

to be the same task. Some of them could work with

me on acquisition, without the computer—using

workbooks—while others are busy working on

courseware. It really depends…it’s an open lesson.”

Teacher I: “In my opinion it’s much more

interesting for them, I see that I manage to engage

some of the students who wouldn’t normally do it.”

Contribution of the e-Learning Environment:

Teacher B: “In my short experience this year, in the

sixth grade, I could tell that when the lesson I

prepared was prepared “right”; it was a challenge

for students, and all of them—down to the very last

one—were engaged in learning. In fact, they were so

busy learning that incidents like “we didn’t hear the

bell” and “butts glued to the seat”, caught us by

surprise and made us giggle over and over again."

6 CONCLUSIONS

Decades ago, policy-makers hoped that the

introduction of computers would lead directly to

better instruction and better achievements.

Nowadays, it is clear that simply providing

computers for schools is not enough (Zucker &

Light, 2009). Schools must realize that successful

1:1 initiatives go beyond the technology itself; they

must also address and include professional

development, training, and support. Both teachers

and students need the training and resources to gain

the skills needed to effectively utilize laptops for

learning (Holcomb, 2009).

Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the

learning processes in a ubiquitous computing

learning environment. In this environment, all

students and teachers were provided with personal

THE FEASIBILITY OF UBIQUITOUS COMPUTING IN SCHOOL - Longitudinal Study in 1:1 Classes Suggests — Time

Matters

495

laptop computers (1:1) and Virtual Learning

Campus (24/7).

Results from this study suggest that employing

one-to-one computers can significantly help increase

student technology proficiency. Students gain

opportunities to acquire technology knowledge and

skills while using the laptops to work on various

tasks for learning, communication, expression, and

exploration. Our findings suggest that one-to-one

computers and related technologies have enriched

students’ learning experiences, expanded their

horizons, and opened more opportunities and

possibilities.

The findings of this research add unique and

positive evidence to the growing body of research

regarding ICT integration in school studies, and

especially one-to-one models. Personal laptop

computers are very powerful in the classroom and

enable the teachers and the students to construct and

enrich their understanding. The one-to-one setting in

ubiquitous computing learning environments may

facilitate achieving the goal of making schools more

engaging and relevant as opposed to the more

common, narrower goal of using computers to

engage students (Zucker, 2008). This study

contributes to the understanding that positive effects

on students and teachers can be achieved only as

part of balanced, longitudinal, comprehensive

initiatives that address changes in education goals,

curricula, teacher training, and assessment.

The one-to-one laptops have provided great

opportunities and resources for teaching and

learning, but have also raised questions regarding

the effectiveness of such learning environments and

cost-effective issues. Results presented here suggest

that "time matters". The statistical analysis as well as

interviews with science teachers and students

revealed that as time passes, and the 1:1 settings

become a routine and a habit of learning in school, it

is easier to detect the advantages of teaching and

learning with personal laptops in learning

environment of ubiquitous computing. Students feel

more motivated, experience higher self-efficacy and

develop better knowledge management skills and

increased technology proficiency for learning.

To summarize, possessing the technology is only

one key piece of the puzzle. Several key factors have

been identified that need to be considered in regard

to the expectations for a 1:1 learning initiative

(Holcomb, 2009). The findings of this study add

unique and positive evidence to the growing body of

research regarding this puzzle - ICT integration in

school, and especially one-to-one models.

REFERENCES

Baldwin, F., 1999. Taking the classroom home.

Appalachia, 32(1), 10–15.

Bebell, D. & Kay, R. 2010. One to One Computing: A

Summary of the Quantitative Results from the

Berkshire Wireless Learning Initiative. Journal of

Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 9(2).

Retrieved 2/23/2011 from: http://www.jtla.org

Beresford-Hill, P., 2000. The Laptop Computer:

Innovation and Practice in a Time of Shifting

Paradigms. Available at: http://www.patana.ac.th/Pubs

/Papers/LTComputers.pdf

Cromwell, S., 1999. Laptops change curriculum—and

students. Education World. Available at: http://www.

educationworld.com/a_curr/curr178.shtml

Guignon, A., 1998. Laptop computers for every student.

Education World. Available at: http://www.education

world.com/a_curr/curr048.shtml

Gulek, J. C. & Demirtas, H., 2005. Learning with

technology: The impact of laptop use on student

achievement. Journal of Technology, Learning, and

Assessment, 3(2).

Holcomb, L. B., 2009. Results & Lessons Learned from

1:1 Laptop Initiatives: A Collective Review.

TechTrends, 53 (6), 49-55.

Inan, F. A. & Lowther, D., 2010. Laptops in the K-12

classrooms: Exploring factors impacting instructional

use. Computers & Education, 55(3), 937-944.

Kozma, R. B., 2003. Technology and Classroom Practices:

An International Study. Journal of Research on

Technology in Education, 36) 1), 1-14.

Maine Education Policy Research Institute (MEPRI),

2003. The Maine Learning Technology Initiative:

Teacher, Student, and School Perspectives Mid-Year

Evaluation Report. Available at: http://www.usm.mai

ne.edu/cepare/pdf/ts/mlti.pdf

Maine Education Policy Research Institute (MEPRI),

2003. The Maine Learning Technology Initiative:

Teacher, Student, and School Perspectives Mid-Year

Evaluation Report. Available at: http://www.usm.mai

ne.edu/cepare/pdf/ts/mlti.pdf

La Mar, E., 2005. Education in the 21st Century: One-to-

One Learning Environments. Retrieved June 26, 2007,

from: http://www.netc.org/circuit/2005/fall/education.

pdf

Lei, J. & Zhao, Y., 2008. One-to-One Computing: What

does it bring to School? Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 39(2) 97-122.

Penuel, W. R., 2006. Implementation and Effects Of One-

to-One Computing Initiatives: A Research Synthesis.

Journal of Research on Technology in Education

38(3), 329-348.

Postman, N., 1998. Five Things We Need to Know About

Technological Change. Available at: http://www.mat.

upm.es/~jcm/neil-postman--five-things.html

Rockman, S., 1998. Powerful tools for schooling: Second

year study of the laptop program. San Francisco, CA.

Russell, M., Bebell, D., & Higgins, J., 2004. Laptop

Learning: A comparison of teaching and learning in

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

496

upper elementary equipped with shared carts of

laptops and permanent 1:1 laptops. Journal of

Educational Computing Research, 30(3), 313–330.

Salomon, G., 2000. Technology and education in the age

of information. Haifa and Tel Aviv: Haifa University

Publishers and Zmora-Bitan .

Salomon, G. & Perkins, D. N., 1998. Individual and social

aspects of learning. Review of Research in Education ,

23, 1-24, (Special issue editors: P. D. Pearson & A.

Iran-Nejad).

Van Weert, T. J., 2006. Education of the twenty-first

century: New professionalism in lifelong learning,

knowledge development and knowledge sharing.

Information and Education Technologies Journal,

11(3-4), 217-237.

Weston, M. E. & Bain, A., 2010. The End of Techno-

Critique: The Naked Truth about 1:1 Laptop Initiatives

and Educational Change. Journal of Technology,

Learning, and Assessment, 9(6). Retrieved 2/23/2011

from: http://www.jtla.org.

Zucker, A., 2008. Transforming Schools with Technology:

How Smart Use of Digital Tools Helps Achieve Six

Key Educational Goals. Harvard Education Press,

Cambridge

Zucker, A. & Light, D., 2009. Laptop Programs for

Students. Science, 323, 5910, 82

THE FEASIBILITY OF UBIQUITOUS COMPUTING IN SCHOOL - Longitudinal Study in 1:1 Classes Suggests — Time

Matters

497