GETTING TO GLOBAL YES!

Designing a Distributed Student Collaboration

Selma Limam Mansar

Information Systems, Carnegie Mellon University, Doha, Qatar

Randy S. Weinberg

Information Systems, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

Benjamin Gan Kok Siew

School of Information Systems, Singapore Management University, Singapore, Singapore

Keywords: Global project management, Global team, Collaboration tools, Mind map, Instructional activities, Learning

outcomes, Assessment, Reflection, Evaluation criteria, Cross culture, Conflict management, Team

assignment, Motivation, Grading rubrics.

Abstract: The authors have taught a course called 'Global Project Management' for four years, engaging students in

three international locations in hands-on distance projects. The distance projects are intended to provide

students with enriching, realistic global project experience. With experience, improved planning and better

coordination, each iteration of the distance projects has improved. In this paper, the authors present lessons

learned and a mind map demonstrating key aspects of design of global hands-on projects.

1 INTRODUCTION

Working with distant colleagues on global projects

adds complexity, especially when they may be

culturally diverse, subject to varying technology

constraints, and demonstrating various work styles

and skills. Universities increasingly recognize the

importance of training a global work force. Students

in many university disciplines can benefit from

exposure to the cross-cultural, communications,

collaborative technologies and project management

considerations of a global project.

However, facilitating such learning in a global

project is neither a trivial nor easy venture for

collaborating instructors, who themselves are not co-

located. Having taught a course called 'Global

Project Management' for four years across three

universities – in the United States, Singapore and

Qatar – the authors, have gained valuable experience

in designing realistic and interesting collaborative

projects for students.

In this paper, we discuss lessons learned and

propose a mind map to represent key elements to

consider in design of collaborative, distance projects

in an academic setting.

2 SURVEY OF

COLLABORATIVE GLOBAL

STUDENT PROJECTS

Over the past decade, an increasing number of

academic 'global experience' courses have been

offered in the broad areas of information systems

(IS), information technology and computer science.

Published articles on these courses indicate a variety

of learning outcomes, design of projects and

operational details. Two emerging types of

contributions are particularly notable:

-Experiential papers that describe various projects,

their execution and lessons learned.

-Conceptual papers that use distance project

experiences to derive frameworks, attributes or

factors influencing outcomes.

229

Limam Mansar S., S. Weinberg R. and Gan Kok Siew B..

GETTING TO GLOBAL YES! - Designing a Distributed Student Collaboration.

DOI: 10.5220/0003490702290234

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2011), pages 229-234

ISBN: 978-989-8425-55-3

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2.1 Experiential Papers

(Volkema and Rivers, 2008) describe an e-mail

based negotiation between graduate students located

in the USA (25 students) and Australia (18 students).

The authors emphasize the articulation of expected

and required tasks, availability of contact details

ahead of the assignment, planning the schedule and

length of the experience, designing appropriate

incentives and a follow-up debriefing.

(Chidanandan et al., 2010) describe a global

project course between undergraduates in USA and

in Turkey. The authors describe the course learning

outcomes, collaboration tools, client set up and the

structure of the project. Upon completion, focus

groups were assessed the global experience.

(Damian, Hadwin and Al-Ani, 2006) report an

experience between three universities, in Canada (12

graduate students), Italy (10 graduate students) and

Australia (8 undergraduate, 2 graduate students).

The authors describe the design, learning outcomes,

engagement with real-world project clients,

assessment and evaluation of the course.

(Purvis, Purvis and Cranefield, 2004) describe a

substantial software development project experience

between a German university (29 students) and a

New Zealand university (5 students). The authors

describe the project’s goal and structure, students’

roles, matching of skills, and note the importance of

sharing common course material and setting up a

suitable collaborative work environment.

(Gan, Limam Mansar and Weinberg, 2010)

describe early experience in teaching a global

project management course.

2.2 Conceptual Papers

(Swigger et. al., 2009) explore factors that affect

software development student team performance.

The authors observed global projects between the

USA and UK and between the USA, Turkey and

Panama. In both instances, ten teams of three

students each were formed mixing a total of 150

undergraduate and graduate students. The authors

demonstrate that differences in culture and attitudes

about groups, prior individual experiences and grade

point averages impact team performance.

(Quinones el at. 2009) analyze teams' mental

models of work process in global collaborative

contexts - how tasks should be assigned, how often

and by what modality communication should occur,

how much effort each member should put forth, and

what constitutes team success. Civil engineering

students enrolled in construction management

courses in the USA (9 students) paired with students

in Israel (2), Brazil (3) and Turkey (2). Professors in

remote locations acted as project clients.

(Ocker and Rosson, 2009) explain the

importance of training students participating in

partially distributed teams to anticipate the issues

with team identification, trust, awareness,

coordination, competence, and conflict.

3 'GLOBAL PROJECT

MANAGEMENT' COURSE

Research and experience demonstrate challenges for

successful global team projects within an academic

course. Some obvious questions: How diverse are

students culturally and in academic preparation?

What will be the impact of differences in calendars

and time zones? What are contractual/legal

constraints for the project? What are the criteria for

assessment? Are the deliverables meeting

expectations explicitly?

At collaborating universities in the United States,

Singapore and Qatar, IS faculty taught co-incident

undergraduate courses called 'Global Project

Management' for four years. To put theory into

practice, students have been assigned to work in

small distributed teams (4 to 5 students drawn across

locations) on a four to five week collaborative

project. Enrollments in the course have ranged from

22 (involving USA and Singapore) to 63 (involving

all three locations). No particular prerequisite in

systems development or project management was

assumed for participating students.

During the first course offering, student teams

were assigned to work with external stakeholders to

prepare project plans for a proposed joint venture

with one of the partner universities. It became

apparent that course logistics, communications, tight

time boxing and managing stakeholder dependencies

substantially reduced the possibility for a satisfying

project experience for the students.

In subsequent years, assigning teams to study

cases in global business ethics, online social

networking, and cross-cultural communications

reduced external dependencies. Ultimately, after

having experimented with a variety of project

parameters (complexity, ambiguity of expectations,

open-endedness, length of project, involvement of

external stakeholders), we settled on a negotiation

exercise as an, effectively bounded, intellectually

interesting, relevant and appealing team project.

(Upton and Staats 2008a), (Upton and Staats 2008b).

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

230

3.1 Collaborative Project Preparation

Students enrolled in the course have had little or no

experience in global collaboration. For these

students, appropriate preparation for project work

along with controlled project scope and manageable

risks have been essential. We have thus designed the

collaborative experience to begin well before the

students are introduced to their project assignment or

to their distant teammates. Common readings,

icebreaker exercises, preparatory background

readings, sample cases and local practice in

negotiations and cultural awareness lessons have

been coordinated across the three locations.

We quickly learned that contradictory (and not

necessarily compatible) assessment criteria and

grading weights resulted in an uneven level of

student commitment and imbalanced expectations

among distant teammates. We addressed this

through development of common grading rubrics

and like weighting of expected commitment. While

instructors in each location have been responsible

for assigning grades and providing clear feedback to

students, the instructors discussed and reconciled all

team grades to avoid deviations within the same

team.

3.2 Instructional Design

Design and execution of a global team-based,

student project can be described through a basic

triple: a learning objective-activity-assessment

model, as consistent with (Ambrose et al. 2010),

1. Learning Objective: To learn the basic

skills and concepts of effective negotiation.

Activity: An in-class negotiating skills exercise

prepared the students for the negotiation project

(PWHC negotiation exercise 2010).

Assessment: Students prepared a negotiation

position based on an existing case study (with partial

information); negotiated with distant partners and

wrote reports detailing the outcomes and describing

the process; and submitted a statement of individual

reflection. The instructors jointly marked the reports

and reflections based on a common grading rubric.

2. Learning Objective: To appreciate the

importance of culture in a global team.

Activity: Students read and discussed articles and

case studies on cross cultural intelligence before the

negotiation project, students completed an

icebreaker exercise to meet global team members

and submitted a brief statement of reflection.

Assessment (Instructors): Credit was awarded for

participation and performing the icebreaker exercise;

the statement of reflection was graded and obvious

problems, communications issues, student absences,

and the like were noted.

3. Learning Objective: To experience the

practical issues when working in a global team.

Activity: Students viewed and discussed various

videos/papers involving tactical issues in global

team collaboration.

Assessment: Students were asked to meet global

milestones and to submit a final collaborative

reflection on the negotiation and the process. The

instructors marked the report on the quality of the

reflection and insights into lessons learned and

team's management of process, schedules, tools,

absentees and 'problem' people.

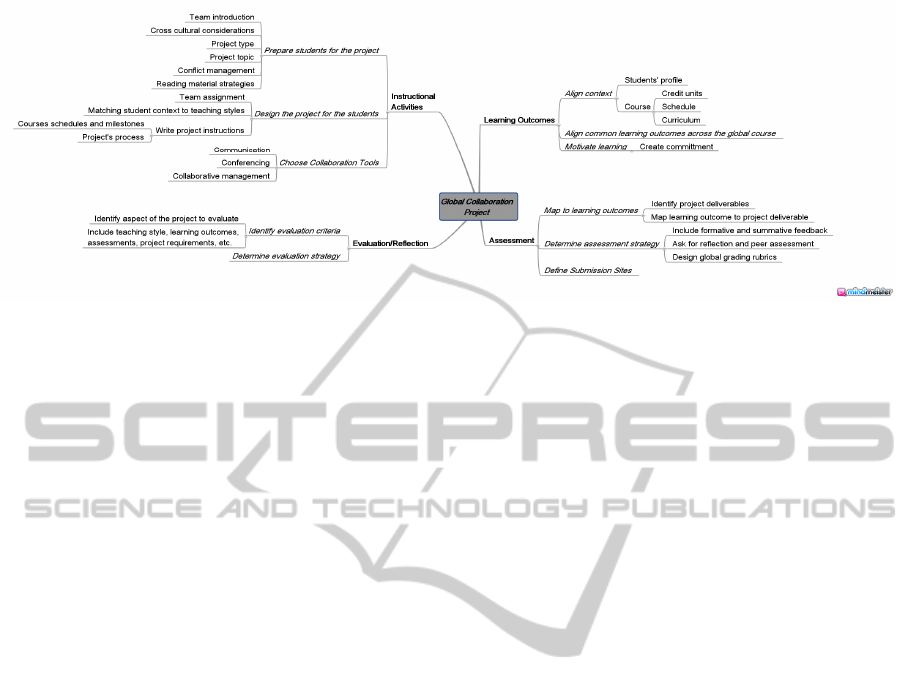

4 GLOBAL PROJECT DESIGN

MIND MAP

Based on our experience designing and teaching

global projects, we propose a mind map to reflect

key elements in project design. It includes the three

essential nodes ‘Learning outcomes’, ‘Instructional

activities’ and ‘Assessment’, plus a fourth node

‘Evaluation / Reflection’ to represent the additional

instructors' debriefing and reflection that takes place

away from students.

4.1 Learning Outcomes

Common Learning outcomes (compatible across

locations), take into consideration the context of the

course as offered at participating universities, which

includes students' experience, prerequisites and

preparation, similar positioning of the course in the

overall curriculum and its relative weight in terms of

credit units, anticipated workload and convenience

for basic logistics.

In our experience, students' motivation across

the institutions generally varies in proportion to the

effort and commitment each student expects to put

forth in relation to the perceived value of the project,

the grade and the overall course.

4.2 Instructional Activities

Preparing students for global projects accounts for a

large part of the outcome and the quality of the

experience. Effective team introductions, cross

cultural awareness, and domain specific background

(negotiation readings/practice) are important.

Common background readings and classroom

activities across locations help set common

GETTING TO GLOBAL YES! - Designing a Distributed Student Collaboration

231

Figure 1: Global Project Design Mind Map.

expectations and a common base of knowledge.

Designing the project to anticipate problems is

important. Things can, and do, go wrong - students

go missing, lose momentum or procrastinate,

misunderstand requirements, and misplace shared

documents in progress. Explicit and clear project

instructions assessment criteria and notices of

individual accountability are important. Reducing

conflicting advice and instructions from the

instructor team reduces potential misunderstandings.

Small details matter including when, where and how

requirements for submitting team and individual

deliverables

Finally, working with distant partners requires a

careful choice of useful collaborative tools, plus

appropriate demonstrations and training, if needed.

4.3 Assessment

An assessment strategy must be defined. We have

found in-class debriefing sessions useful to identify

and discuss common misunderstandings and

common issues. We assess team deliverables with a

common rubric and use individual statements of

reflection and peer assessment surveys to gauge

team members' relative contributions..

4.4 Evaluation/Reflection

Mistakes, misunderstandings, contradictory and

unclear communications among instructors and with

students complicate course flow. It is thus important

for instructors to evaluate the effectiveness of the

course, projects, student interactions, results and

methods. The evaluation of such an experience

requires a prior discussion of what should be

evaluated (evaluation criteria) and how it should be

conducted (evaluation strategies). With an eye

toward improvement in the future, attention to

increased efficiency, tightened coordination, better

assessment and reduction of anticipated pitfalls is

important.

5 STUDENT SURVEY AND

REFLECTIONS

In 2010, students were surveyed before and after the

negotiation project. Students were undergraduates in

their second to fourth year of study. 87% of the

students were majoring in IS. Other students were

enrolled in a business, humanities or social sciences

major.

Both surveys included questions about the

experience, including quantitative questions (for

example, "Rank the skills needed for a successful

global project.") and qualitative questions (in the

pre-survey: "What skills do you think you can bring

to the global negotiation project?” "What is

motivating you to take this course?”; in the post-

survey "What was the most rewarding aspect of the

global project?” "What do you think you did well on

your team or on your project", "What would you do

differently next time?", "What did your distant

counterparts do well?"). These questions are

variations on the survey questions described in (Topi

et al., 2010) and (Volkema and Rivers, 2008) and

the skill set listed in (Govindarajan and Gupta, 2001)

and (Gotel, Kulkarni and Phal, 2009).

Students indicated that teamwork skills, project

management skills and cultural intelligence were

expected to be the most important skills for a

successful global negotiation project. Despite

variations in majors and backgrounds, we note that

all three cohorts agreed on the same three skills (1 =

highest rank; 8 = lowest rank). See Table 2.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

232

Table 1: Essential Skills for Global Project Management

Experience (pre-survey).

Skill Factors U.S. Singapore Middle East All

Rank Rank Rank Rank

Cultural Intelligence 3 3 3 3

Teamwork Skill 1 1 2 1

Project Management Skills 2 2 1 2

Mastery of English 5 6 7 7

Domain Skill 7 7 5 6

Global Project Experience 5 4 6 5

Collaboration Tools 4 4 3 4

Other 8 8 8 8

Surveys indicated that students were

intrinsically motivated to enroll in the global project

management course (as opposed to fulfilling

distribution requirement or upon recommendations

of friends) and that was consistent across the three

locations. This was a useful predictor for the success

of the experience as research shows that intrinsic

value is a better motivator than the expectation of

some reward or grade (Ambrose et al., 2010).

5.1 Students’ Reflections

Students related a general feeling that the experience

was rewarding and that the course was, despite the

challenges, useful and interesting.

In their written reflections, students commented on

their preparation for the project. We noted that

students seemed to find more challenges in the

planning of the experience (planning meetings,

paying attention to time zones, motivation) and

fewer challenges in classic project management

issues such as the collaboration, planning and

delivery of work products, and the differences in

work ethics. This is a different result from the

survey of senior managers in (Govindarajan and

Gupta, 2001).

While students generally appreciated the ice

breaker negotiation exercise ("I believe getting a

chance to know all teammates through the Ice

Breaker case is a very important first step, which

helped us a lot"), some indicated they would have

preferred an ice breaker that would help them to

know each other more ("I think a more personal ice

breaker would be cool - like learning about team

member interests").

Although all three sites shared common material

and online references, these were not made available

on one common course content management

platform. As one student commented, "having a

common communication media i.e. wiki or vista for

all three schools" would enhance the experience and

reinforce consistent global expectations.

Students noted that understanding partners’

culture impacts the team’s collaboration ("...I’ve

also had personal Skype conversations with our

Singaporean counterparts, and they are very fun and

hardworking people. I think what will stick with me

from this global encounter is their work ethic, which

is extremely amazing. "; “Through the ice-breaker

exercise I discovered certain traits, such as openness

in expressing themselves in a conversation: joking

about almost everything, it was decided that we

might have more success if we remain slightly

informal in our discussion…")

Students ranked collaborative tools expected and

used. Students expected to use primarily Skype,

videoconferencing and email. They actually made

little use of videoconferencing, replacing it by

instant messaging. Students noted the usefulness of a

collaborative writing tool such as Google Docs.

Other collaboration tools used include discussion

boards, online file sharing, and wikis.

Students also realized the value of meeting

structure and some facilitation ("Sometimes during

the negotiation, we can encounter a standstill where

everyone keeps silent and not knowing what to

comment on"; "We adopted a role-based style during

the negotiation process, I was in charge of carrying

out the conversation with the other party, my

teammate would input the main details into Google

docs"; "The problem we faced is the lack of ability

to ensure all members are focusing and actively

participating in the conference").

Overall, students reported a high level of

satisfaction with the project ("This experience of

working with students in SE Asia was the best thing

I had ever done in my life. I learned a lot about the

global team project and how to manage working

with people from different parts of the world. I

really hope to have such an experience in the

following years. Moreover, I'm hoping to keep in

touch with my team…"; "Being able to actually

work with students on the other side of the globe and

coming to agreements was very rewarding"; "This

course gave me a chance to experience collaborating

with a person who I might never meet with. This

literally made me feel the effect of

globalization…").

6 CONCLUSIONS

The authors recommend paying attention to three

main instructional challenges: 1) the time effort

GETTING TO GLOBAL YES! - Designing a Distributed Student Collaboration

233

needed to coordinate and teach a global project is

substantially more than for a local project.

Coordinating calendars, assignments, readings, due

dates, team rosters; grading student work in a timely

and consistent way; providing IT support for video

calls and software tools complicates all aspects of

course preparation and delivery. Intervening when

students find their distance relationships not working

increases complexity. 2) Motivating students to keep

up the global communication through a fast moving

project schedule is a real challenge. Procrastination

and uncoordinated work add to pressure to meet

hard deadlines. Intermediate project deliverables to

demonstrate progress on the project can alleviate; 3)

Managing student problems, such as "global free

riders" are exacerbated. Distribution of work and

responsibility within each team should be carefully

watched.

In the future, the authors will continue to

explore how different choices for project design

would influence the global team experience and

success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first author would like to acknowledge that the

work for this paper was partly funded by the Qatar

Foundation for Education, Science and Community

Development. The statements made herein are solely

the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect

any official position by the Qatar Foundation or

Carnegie Mellon University.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, S., Bridges, M., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M., and

Norman, M., 2010. How Learning Works: Seven

Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. In San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Chidanandan, A., Russell-Dag, L., Laxer, C., and Ayfer,

R., 2010. In Their Words: Students Feedback on an

International Project Collaboration. In SIGCSE’10,

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, ACM, March 10-13,

2010.

Damian, D., Hadwin, A., and Al-Ani, B., 2006.

Instructional Design and Assessment Strategies for

Teaching Global Software Development: A

framework. In ICSE’06, Shanghai, China, ACM, May

20-28, 2006, pp. 685-690.

Fisher, R., Ury, W., and Paton, B., 2003. Getting to Yes,

Negotiating an Agreement without Giving. In 2

nd

ed.

Simon & Schuster Audio.

Gan, B.K.S., Weinberg, R., and Mansar, S., 2010. Global

Project Management: Pedagogy For Distributed

Teams. In Proceedings of Global Learn Asia Pacific

2010, Penang, Malaysia.

Gotel, O., Kulkarni, V., and Phal, D., 2009. Evolving an

infrastructure for student global software development

projects: lessons for industry. In ISEC’09, Pune, India,

ACM, 23-26 February 2009, pp. 117-125.

Govindarajan, V., and Gupta, A.K., 2001. Building an

Effective Global Business Team. In MIT Sloan

Management Review, 42 (4), 2001, pp. 63-71.

Ocker, R., and Rosson, M.B., 2009. Training students to

work effectively in partially distributed teams. In ACM

Transactional Computing Education 9, 1, Article 6,

March 2009, 24 pages.

Purvis, M., Purvis, M., and Cranefield, S., 2004.

Educational Experiences from a Global Software

Engineering (GSE) Project. In 6

th

Australasian

Computing Education Conference (ACE2004),

Dunedin. Conferences in Research and Practice in

Information technology, Vol. 30, R. Lister and A.

Young, Ed., 2004, pp. 269-275.

PWHC negotiation exercise,

www.studentnet.manchester.ac.uk/media/media,14530

5,en.doc; last retrieved May 2010.

Quinones, P.A., Fussell, S.R., Soibelman, L., and Akinei.

B., 2009. Bridging the Gap: Discovering Mental

Models in Globally Collaborative Contexts. In

IWIC’09, Palo Alto, California, USA, ACM, February

20-21 2009, pp. 101-110.

Staff Development Unit, University of Birmingham, 2010.

A Model of Course Design – Commentary.

Swigger, K., Alpaslan, F.N., Lopez, V., Brazile, R.,

Dafoulas, G., and Serce, F.C., 2009. Structural Factors

that Affect Global Software Development Learning

Team Performance. In SIGMIS-CPR’09, Limerick,

Ireland, May 28-30, 2009, pp. 187-195.

Topi, H., Valacich, J.S., Wright, R.T., Kaiser, K.M.,

Nunamaker Jr., J.F., Sipior, J.C. and de Vreede, G.J.,

2010, IS 2010 Curriculum Guidelines for

Undergraduate Degree Programs in Information

Systems. In ACM 2010 Information Systems

Curriculum.

Upton, D.M., and Staats, B.R., 2008a. Tegan, c.c.c. In

Harvard Business School, Case #9-609-038.

Upton, D.M. and Staats, B.R., 2008b. Hrad Technika. In

Harvard Business School, Case #9-609-039.

Volkema, R. and Rivers, C., 2008. Negotiating on the

Internet: Insights From a Cross-Cultural Exercise. In

Journal of Education for Business, Vol. 83, N. 3, Jan-

Feb 2008, p.165-172.

Westerlund, M.J., 2008. Super performance in a remote

global team. In Performance Improvement, 47, 5,

ABI/INFORM Global, May/June 2008, pp. 32-37.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

234