MEASURING THE CAPABILITY OF LIVING A HEALTHY LIFE

WITH FUZZY LOGIC IN A GENDER PERSPECTIVE

Tindara Addabbo

1

, Gisella Facchinetti

2

and Tommaso Pirotti

1

1

Dipartimento di Economia Politica, Facolt

`

a di Economia, Universit

`

a di Modena e Reggio Emilia

Viale Berengario 51, Modena (MO), Italy

2

Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche e Matematico Statistiche, Universit

`

a del Salento

Centro Ecotekne Pal. C - S.P. 6, Lecce - Monteroni, Lecce (LE), Italy

Keywords:

Fuzzy logic, Health, Capabilities, Gender perspective.

Abstract:

The capability of living a healthy life may be considered a key dimension in the construction of individual

well-being. It is itself the outcome of a complex set of indicators also including subjective indicators. This

paper measures health at an individual level by using fuzzy logic to maintain the complexity of its definition

while providing a crisp indicator of the level of health which may be disaggregated in relevant intermediate

variables. The system has been implemented on the basis of the Italian National Statistical Institute (ISTAT)

survey on health conditions, the results of which show a higher level of gender inequality in health than ,may

be obtained by the traditional techniques used to measure health. We do find that when controlling for age,

women are still characterized by poorer health conditions. Data disaggregated by regional area show a degree

of variability in the outcome which may be connected to the varying policies implemented in different regions

of Italy.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper presents the initial results of a wider re-

search project supported by the Italian Ministry of

Health on gender and health

1

. It is made up of six

projects, each dealing with different aspects from a

gender perspective. One of these projects, that devel-

oped by the research unit of the University of Mod-

ena & Reggio Emilia, is concerned with the socio-

economic determinants of health from a gender per-

spective. We thank the expert group on health (Sivana

Borsari, Maria Cristina Florini and Erica Villa) for

their comments on the construction of the model used

to measure health; Anna Maccagnan for her elabo-

rations of the microdata and the other participants in

the project for their comments on a previous version

of this paper.

This idea is supported by the increasing attention

given in recent years to gender differences and in-

1

This paper is part of the research activities of the Uni-

versity of Modena & Reggio Emilia research unit within the

broader project funded by the Italian Ministry of Health:

“La medicina di genere come obiettivo strategico per la

sanit

`

a pubblica: l’appropriatezza della cura per la salute

della donna”.

equalities, which no longer come down to mere bi-

ological factors also seen within a wider perspective

that includes the concept of women’s capability of

living a healthy life. Nonetheless, in Italy we ob-

serve a systematic lack of appreciation of “gender-

oriented health”, fundamental to guaranteeing equity

and planning efficient health and social services. In

our group’s project, the evaluation of the gender fac-

tor will refer to four dimensions: access to services,

objective and subjective health, life styles and states

of well-being. The classical definition of a country’s

welł-being is usually connected with GDP measure-

ments. The need to take the health dimension into

account in the evaluation of well-being in order to go

beyond GDP and towards an extended measurement

of human development has been widely recognized

in the literature (Fleurbaey, 2009), (Stiglitz et al.,

2009) leading to the proposal of indicators that mea-

sure human development and explicitly include mea-

sures of the health dimension such as the Human De-

velopment Index (United Nations Development Pro-

grammes, 1990). Here we follow Sen’s capability

approach (Sen, 1993) by measuring well-being in its

multidimensional setting devoting special attention to

one dimension: the capability of living a healthy life.

389

Addabbo T., Facchinetti G. and Pirotti T..

MEASURING THE CAPABILITY OF LIVING A HEALTHY LIFE WITH FUZZY LOGIC IN A GENDER PERSPECTIVE.

DOI: 10.5220/0003672403890398

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Theory and Applications (FCTA-2011), pages 389-398

ISBN: 978-989-8425-83-6

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

In defining this capability we are aware of its com-

plexity stemming from various dimensions (physical

vs mental health; subjective vs objective) and bound

up in the social environment that affects its develop-

ment. In order not to lose its complexity while mea-

suring it, we adopt fuzzy logic. Fuzzy logic is ideal,

in our opinion, since it allows us to get to the heart

of the development process of the capability without

losing the various dimensions that interact to define it.

An attempt to exploit fuzzy logic to measure

healthy living has previously been undertaken by

Pirotti (2006) using Italian microdata (yet with a lim-

ited number of variables to define health) and by

Addabbo et al. (2010a) to measure the capability of

living a healthy life in the Modena district. However,

this is the first attempt to implement a fuzzy infer-

ence system on the definition of living a healthy life

with a large number of dimensions at national level

in Italy. Due to the different methodology adopted,

this work differs in methodological terms, from other

previously published papers, dealing with the issue of

health from a capability perspective (Kuklys, 2003).

The fuzzy technique in fact allows us to preserve the

complexity of the measuring issue and, at the same

time through a system of rules,to make explicit the

relationships between the variables that help to assess

the degree of capability development. The presence in

the project of experts in health problems has helped us

in fuzzy inference building, in the fuzzification of in-

puts and in the rule construction. But our purpose is

also to compare our “non main stream” approach with

a classical method to look at differences, faults and

values. So we have looked at the SF12 questionnaire,

which is an instrument adoptedto measure the “health

level” widely used (in over 40 countries) and vali-

dated by the international scientific community. It has

been in use since 1992, when the Medical Outcomes

Study (MOS) developed a standardized survey form

made up of 115 items synthesized in 12 steps. The

MOS was a two year study of patients with chronic

conditions that set up to measure the quality of life,

including physical, mental and general health. The

SF-12 requires only two minutes to be filled in, and it

can be self-reported. It can be added to larger surveys

or printed on a single sheet and easily faxed away.

Due to its handiness, yet still being of great meaning-

fulness as stated before, during the last decade the use

of SF-12 has spread throughout the world. Even the

Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) decided

to add an SF-12 section to its 2005 national health sur-

vey. So we carried out our analysis using the Italian

Statistical National Institute survey on health condi-

tions in 2004-2005, which provides a set of variables

well-suited to the information needs for the treatment

of the topic in question. Particularly relevant for the

purposes of this work is the information on the mea-

surement of health-related elements of quality of life,

such as obesity, certain diseases, disabilities, on spe-

cialist visits and visits to the ER. Moreover, the survey

contains information on factors that may affect the ca-

pability of living a healthy life and/or its conversion in

functionings. Amongst them, we may identify in the

light of Sen’s capability approach: Socio/Institutional

factors. These refer to the presence of social services

in the region where the individual lives. In a fur-

ther extension, we will also include data on the health

structure available. In this specification of the model,

we do take into account these factors by including re-

gional dummies (given the uneven presence of health

services in the Italian regions). The individual fac-

tors:age, gender, educational level and employment

conditions. We expect to find a negative correlation

between age and health status due to the worsening

of health conditions experienced by the elderly. As

regards the level of education, it is now documented

extensively in the international literature that higher

education is usually associated to a better health. This

is due to a greater awareness of the importance of

lifestyles on health and also to improved access to

health services(Mackenbach et al., 2003). Further-

more a higher education level allows for a wider

choice about of jobs that individuals may take and ac-

cess to posts characterized by healthier conditions as

well as a higher income, which may improve access to

health services. Individuals employment status may

be considered a crucial individual conversion factor:

some contractual arrangements, like temporary work

contracts, given their high level of instability, may

have a negative effect on health, mainly due to the

stress induced by the uncertainty linked to the job se-

curity (Addabbo and Favaro, 2011). Individual health

status, as experienced in literature, is also influenced

by familiar conversion factors such as parents’ educa-

tion level, marital status, parents’ level of health, fam-

ily income and housing conditions. These factors can

affect lifestyles, for example, or access to health ser-

vices.The fuzzy approach we propose provides all the

values of the knowledge-based systems. Everything

is transparent; the rule blocks, which translate the

weights proposed by the experts, are readable and al-

ways justified and may be changed if necessary. SF12

applied to the ISTAT 2005 national survey on health is

not able to produce this effect as its results are based

on a weighted average. Moreover, the weights used

to compute the weighted average were evaluated in

1994 using data based on the 1992 MOS survey for

the USA (Ware Jr et al., 1998); thus, one may question

the validity of the same weights years later and in a

FCTA 2011 - International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

390

different country. On the other hand, though affected

by the reliability of experts and the need to use a more

complex methodology, fuzzy logic with its tree struc-

ture of the inference system, allows us to understand

the inputs that produce the final result and to improve

the final outcome by devising policies in those areas

that appear to be less developed.

2 THE USE OF A FUZZY

INFERENCE SYSTEM WITHIN

A CAPABILITY APPROACH

FRAMEWORK

Fuzzy logic has been previously used to measure

poverty and well-being by Cheli & Lemmi (1995)

and, by following the capability approach, by Chi-

appero Martinetti (2000). However the method they

follow is different from the one adopted in our con-

tribution. In fact they use a mix of probability theory

and fuzzy logic and data are used to build variables

distributions similar to aleatory distributions, while

the aggregation functions are similar to weighted av-

erages, explained on the basis of weights that are de-

termined ex-ante. In this method the creation of the

membership functions relies on the distribution of ev-

ery single variable in the population of reference. In

our contribution, we use fuzzy logic following more

heuristic methods, which, in our opinion, are more ef-

fective and able to reflect the multidimensionality of

the issue of measuring capabilities without depending

on current data. The system is constructed by follow-

ing experts’ judgments and rules based on their ex-

perience and/or on the literature. The experts start by

choosing the ‘input’ variables, they then propose their

aggregation with ‘intermediate’ variables and then to

an output variable. The latter is interpreted as the fi-

nal evaluation of the development of the functionings

of the capability under analysis. Experts are also re-

sponsible for identifying the membership functions of

the initial variables; therefore, unlike the method fol-

lowed by Chiappero Martinetti (2000) the latter do

not depend on the current available data, but are set

by the experts on the basis of their experience. Ex-

perts suggest how to aggregate input variables by us-

ing only linguistic rules and attributes without seing

the data in advance. The experts’ linguistic rules are

translated formally by mathematicians. The proposed

system of rules is then explicitly described ‘rule by

rule’, allowing us to understand to what extent the re-

sults depend on the ratings determined by the experts.

The method we apply here to measure of the capabil-

ity of living a healthy life has already been used on an

experimental basis for the measurement of well-being

within the capability approach, (Addabbo et al., 2004;

Addabbo et al., 2006; Addabbo and Di Tommaso,

2008; Addabbo et al., 2010b) and specifically for the

measurement of the capability of living a healthy life

by Pirotti (2006) and by Addabbo, Chiarolanza, Fus-

caldo and Pirotti (2010).

3 THE SHORT FORM 12 (SF-12)

This questionnaire is a set of 12 questions relating to

the condition perceived over the four weeks prior to

the interview, allowing us to compile two indexes: the

Physical Component Summary (PCS) (index of phys-

ical health) and Mental Component Summary (MCS)

(index of mental health), with values from 0 to 100.

Because of its brevity and simplicity, it is widely used

in more than 40 countries and has been validated by

the international scientific community(Gandek et al.,

1998). SF-12 is based upon a 12 questions tool of

analysis that has its roots in the instruments used since

1992, when the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) de-

veloped a standardized survey form consisting of 115

items synthesized in 12 steps. MOS was a two-

year study of patients with chronic illnesses which

aimed to measure the quality of life, including phys-

ical, mental and general health. As part of the MOS,

RAND, (acronym of Research and Development) de-

veloped the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-

36): a set of generic, coherent and easily adminis-

tered quality-of-life indicators. These measurements

rely upon patient’s self-reporting; thus the adminis-

tration of the survey is very handy, yet a wide range

of literature has backed up the quality of the results

assessed by this survey. Through the analysis of case

studies collected during the MOS project, RAND se-

lected eight groups of questions, or health concepts,

from the original 40 (Ware Jr et al., 1996). Those

chosen represent the most frequently measured con-

cepts in widely-used health surveys and those most af-

fected by disease and treatment (Ware Jr et al., 1993).

The questionnaire items selected also represent mul-

tiple operational indicators of health, including: be-

havioural function and dysfunction, distress and well-

being, objective reports and subjective ratings, and

both favourable and unfavourable self-evaluations of

general health status (Ware Jr et al., 1993). This psy-

chometric survey was first developed in the US and

then developed internationally over the last 10 years.

The SF-36 idea is based on a three-level tree scheme,

starting from the single 36 items, aggregating them

in eight scales and defining the summary measures of

physical and mental health on the third level (respec-

MEASURING THE CAPABILITY OF LIVING A HEALTHY LIFE WITH FUZZY LOGIC IN A GENDER

PERSPECTIVE

391

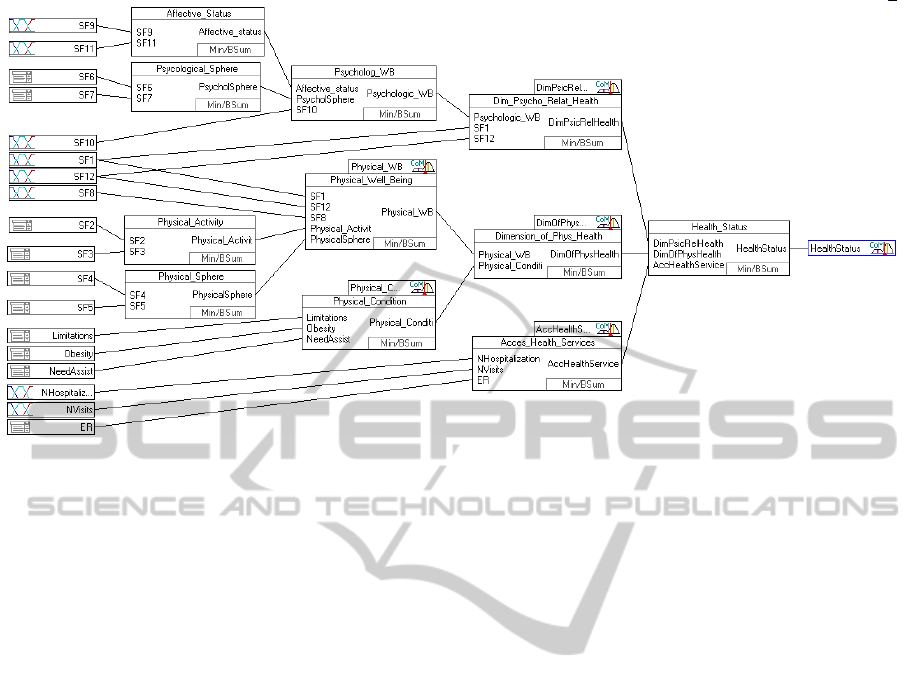

Figure 1: The chosen fuzzy inference system tree.

tively PCS and MCS). The discovery that SF-36 phys-

ical and mental component summary scales (referred

to as PCS-36 and MCS-36 respectively) capture about

85% of the reliable variance in the eight-scale SF-36

health profile provided a new strategy for meeting this

challenge. While two outcome measures are satisfac-

tory for many purposes, a survey with fewer ques-

tionnaire items could be constructed to estimate these

outcomes. Predictive studies supported this strategy.

12 SF-36 items and improved scoring algorithms re-

produced at least 90% of the variance in PCS-36 and

MCS-36 in both general and patient populations, and

reproduced the profile of eight SF-36 health concepts

sufficiently for large sample studies. The reproduc-

tions of PCS-36 and MCS-36 proved to be accurate

enough to warrant the use of published norms for SF-

36 summary measures in interpreting SF-12 summary

measures. The SF-12 Survey represents an efficient

synthesis of SF-36. Several empirical studies also

conducted in European populations showed that the

synthetic indices of the SF-12 correlated with the cor-

responding indices of the SF-36 with a range of values

between 0.93 and 0.97 (Gandek et al., 1998). SF-12

requires only two minutes to be filled in, and it may

be self-reported. It can be added to larger surveys or

printed on a single sheet and easily faxed away. Due

to its handiness, yet still being of great meaningful-

ness as stated before, over the last decade the use of

SF-12 has spread all over the world. Even the Ital-

ian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) decided to

add an SF-12 section to its 2005 national survey on

health. We will use variables collected in the ISTAT

Survey by using SF-12s to construct our fuzzy infer-

ence system (FIS) on the capability of living a healthy

life and compare the results obtained through FIS to

the original SF-12 outputs.

4 A FUZZY INFERENCE SYSTEM

TO MEASURE THE HEALTH

OF THE ITALIAN

POPULATION

A fuzzy inference system (FIS) (Figure 1) may be

graphically represented as a tree. Starting from the

right hand side we see the output of the system: the

health status. Moving to the left, the tree grows and

presents various nodes, representing the intermediate

variables describing the macro-indicators, through to

the smallest branches which show the initial inputs.

The basic input variables that appear on the left side

of the tree conceptually pertain to three different ar-

eas: the first, concerning perceived physical and men-

tal health; the second, whicj attains to more objective

indicators of physical health, and the third, which re-

gards access to health services. Lifestyles were not

taken into account because they represent risk fac-

tors in the medium and long term but they are not

“manifestations” of the immediate state of health of

individuals. What we aim to do here is instead to

understand the health status over a relatively short

period, such as the last four weeks. Instead of di-

rectly using SF-12 outcomes, available as a ready to

use variable, we decided to build a “fuzzy SF-12”,

the results of which (Physical Well-being and Dimen-

FCTA 2011 - International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

392

Table 1: The system variables: abbreviations and relative questions.

ER Did you need assistance from the ER during the last 12 months?

Limitations Did you experience limitations during at least the last six months?

NeedAssist Do you think that you need house care assistance?

NHospitalizations Number of Hospitalizations in the last 3 months

NVisits Number of visits during the last 4 weeks

Obesity Are you obese?

SF1 In general, would you say your health is: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?

SF10 How much of the time during the past 4 weeks did you have a lot of energy?

SF11 How much of the time during the past 4 weeks have you felt downhearted and blue?

SF12 During the past 4 weeks, how much of the time has your physical health or emo-

tional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting with friends, rela-

tives, etc.)?

SF2 Does your health now limit you in moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing

a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf

SF3 Does your health now limit you in climbing several flights of stairs?

SF4 During the past 4 weeks (relatively to your work or other regular daily activities as a

result of any physical problems) did you accomplished less than you would like?

SF5 During the past 4 weeks, as a result of any physical problems, were you limited in the

kind of work or other regular daily activities?

SF6 During the past 4 weeks (relatively to your work or other regular daily activities as a

result of any emotional problems such as feeling depressed or anxious) did you accom-

plished less than you would like?

SF7 During the past 4 weeks, as a result of any emotional problems such as feeling de-

pressed or anxious, didn’t you do work or other regular daily activities as carefully as

usual?

SF8 During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work (includ-

ing both paid work and housework)?

SF9 How much of the time during the past 4 weeks have you felt calm and peaceful?

AccHealthService Access to the Health Services

DimOfPhysHealth Dimension of Physical Health

DimPsicRelHealth Dimension of Psycho-Relational Health

HealthStatus Health Status

Physical Conditi Physical Condition

Physical WB Physical Well-being

Affective status Affective Status

Physical Activit Physical Activity

PhysicalSphere Physical Sphere

PsycholSphere Psychological Sphere

sion of Psychological and Relational Health) could

be used as intermediate variables for the final “sta-

tus of health index” and at the same time, be com-

pared to the original Physical Component Summary

(PCS) SF-12 index of physical health and the Mental

Component Summary (MCS) SF-12 index of men-

tal health. The reason for this choice is that, as al-

ready stated, even though the SF-36 idea relies on a

tree scheme basis, SF-12 outcomes are obtained as a

reduction of the variables based on a statistical ba-

sis that makes impossible to reconnect the final SF-

12 analysis scheme to the original logic that guided

the researchers in first place. According to the SF-

12 operative manual, MCS and PCS are built through

the use of weighted means, using regressive coeffi-

cients coming from analysis based on the American

population. However, the coefficients are given and

derived from SF-36 coefficients that, in turn, come

from the original 115 questions of the MOS survey;

therefore, it is hard to trace back the path that led

to the construction of the coefficients. Moreover, we

believe that the assumption that the coefficients esti-

mated using a sample representative of the American

population in the mid ‘90s remains valid even when

applied to the analysis of other countries and almost

ten years later is rather strained. There is no guaran-

tee of the validity of results. As a last consideration,

we must notice that MCS and PCS are two indica-

MEASURING THE CAPABILITY OF LIVING A HEALTHY LIFE WITH FUZZY LOGIC IN A GENDER

PERSPECTIVE

393

tors that have been designed to be two well separated

indexes, not to be bundled toghether in a single syn-

thetic health indicator. Instead in our opinion, sup-

ported by our health experts’ opinions and by the lit-

erature, it is possible to proceed with the construction

of a third synthetic index that takes into account ele-

ments of both dimensions. For this reason, even if we

assume that SF-12 results are proven to be reliable,

we wanted to produce indexes whose results could

arise from immediately understandable choices and

that could also produce a unified health index. Our

“fuzzy SF-12” is hence an expert system, driven by

experts’ judgments, so that the survey outcomes are

the direct reflection of a precise will, connected to the

analysis of the specific Italian framework. Moreover

in our evaluation system, following Wagstaff et alt.

(1991) we have decided to propose not just the PCS

and MCS scheme, but three macro-indicators (physi-

cal and mental health, physical condition and access

to the health services). The “health” of the fuzzy sys-

tem’s final output (Health Status) investigated from

a physical point of view (physical health dimension)

and a mental or psychological point of view (mental

health dimension) use the items in the SF-12 survey;

however, it is not just the result of the use of these

items: firstly we have a third dimension, bound up in

the actual use of services and structures connected to

the healthcare service. Thus in our vision there are

not just two dimensions but three. We have noticed

that SF-12 items are far too connected to a subjec-

tive evaluation of health. This third leg of the tree

helps to connect subjective to objective information.

In addition to this the physical health dimension is not

just the result of the elaboration of the SF-12 items,

but, for the same reason, we have added physical ob-

jective data. Looking at the PCS items, it becomes

clear that the items attain to “Physical Well-being”.

For a comprehensive evaluation of health, its percep-

tion represents an important reference as it helps to

capture the multidimensionality of the concept itself,

defined according to the World Health Organization

as a state of “complete physical, mental and social

wellbeing” (Di Martino, 2008). Adding information

about people’s physical conditions greatly helps to

better evaluate the dimension of physical health. In

this way functional indicators define health in rela-

tion to the loss of skills in performing ‘normal’ daily

activities. Medical indicators identify the presence of

specific diseases or disabling conditions diagnosed by

physicians. Subjective ones,on the other hand, de-

fine health according to the perception of the indi-

vidual. In a fuzzy system, the same variable can be

used several times. The complexity of relationships

between different determinants of individual health is

indicated by the presence of some input variables, in

keeping with the literature in more than one dimen-

sion of the state of individual health. The “access to

health care services” dimension comprises informa-

tion (or basic variables) as the number of hospital-

izations (excluding childbirth hospitalizations), over

the past three months, the number of accesses to the

Emergency Room (ER) over the past 12 months, not

counting the so called white codes, meaning wrong

or unnecessary accesses to the ER, and the number

of doctors’s visits, excluding dental visits. As may be

easily understood, the effect of these variables (and of

the intermediate index) on the final variable, “individ-

ual health status” is negative because a high number

of accesses to health services is likely to be connected

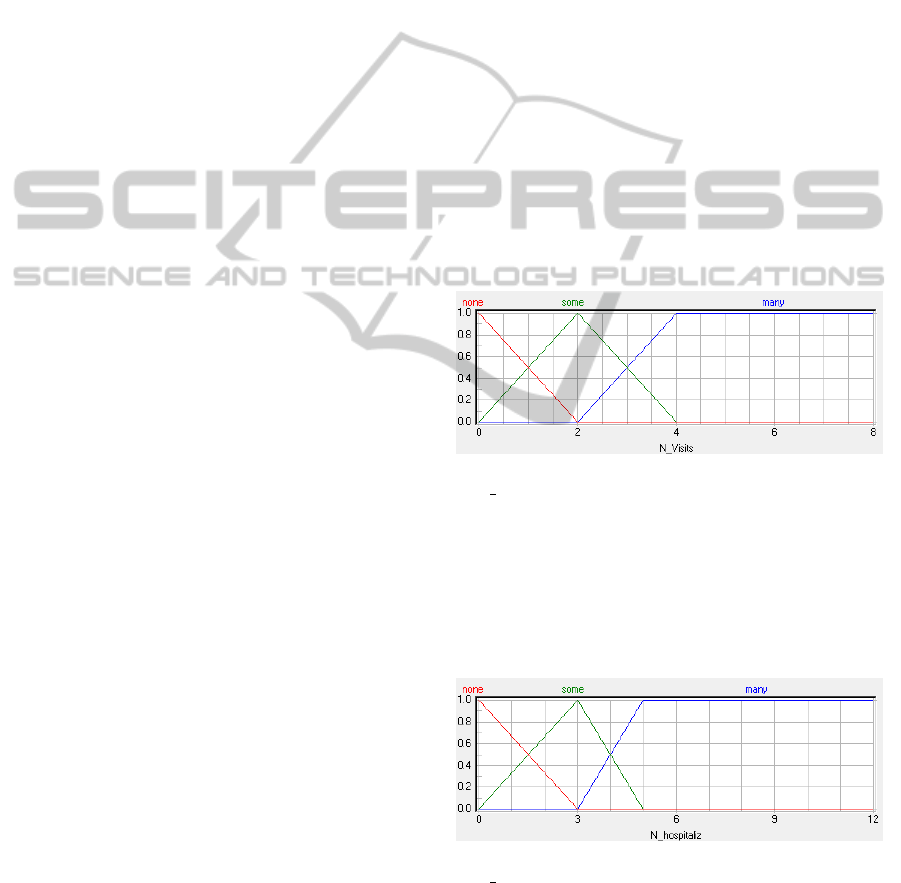

to a poor health status. In order to fuzzify the inputs,

the experts have decided to identify three linguistic

membership functions per each variable, respectively

named “none”, “some” and “many”. These are ap-

plied to “number of visits”, for which 0 is connected

to the spike of none, 2 to the spike of some and 4 to

the spike of many.

Figure 2: Fuzzyfication scheme and membership functions

of N Visits.

The same membership functions (MBFs) were ap-

plied to the number of hospitalizations, so that 0 is

associated to none, some to 3 and many to 5. The ac-

cess to the ER instead is just a dummy and it tells us

whether an individual had to ask for assistance over

the previous 12 months.

Figure 3: Fuzzyfication scheme and membership functions

of N Hospitaliz.

The aggregation method amongst fuzzified vari-

ables is not an explicit function, but it is expressed in

the form of the explicit rule block, where every pos-

sible interaction between the fuzzy sets (for instance

none, some and many( is represented by a block line

FCTA 2011 - International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

394

in the “IF” part, while the effect on the variable on

which they insist is represented by a synthetic lexical

effect in the “THEN” part. Since more than one rule

may be activated at the same time, every rule is ac-

tivated with the MIN aggregating rule, which stands

for the minimum level of activation between the sets

(always between 0 and 1), acting in the “IF” part. If

a term is activated with a level of 0, it means that it

is absolutely not activated (the data do not belong to

that fuzzy set). On the other hand if the level is 1 it

means that the term is fully activated, meaning that

the data belongs entirely to that specific term and just

to that one. Every number in between stands for a

partial belonging between different fuzzy sets. The

way the membership degree to a particular fuzzy set

is decided depends on the specific membership func-

tion of every fuzzy set. On the THEN side, there may

be many lines that lead to the same lexical effect. If

there are more activated lines in the same rule block

with the same effect, the chosen aggregation rule is

the bounded sum (BSUM): all the effect activation

levels get summed up tol the level of 1. Any effect

added to that level produces no result. The described

aggregating process, through the use of rule blocks, is

iterated from the left to the right of the system tree. At

the end of the process, to make the results intelligible

to human beings it is necessary to de-fuzzify them.

This is done with a system called “Center of Maxi-

mum” or, in short, CoM: if more effect are active at

the same time in the final rule block, only the highest

will be considered and the result will be equivalent to

the peak of its membership function.

The variable named “Dimension of Physical

Health” was designed to be an aggregation between

the “Physical condition” and the “Physical Well-

being”. The “Physical condition” identifies health

conditions caused by chronic or incapacitating dis-

eases through objective indicators such as the pres-

ence of limitations for at least six months, need for

home care, and finally the presence of obesity, dis-

criminated by body mass index values over 30 among

over 18s, while in the population below 18 years of

age, the corrections suggested in the literature were

adopted (Cole et al., 2000). While the first of the

three basic indicators may be seen as a categorical

variable on three levels, the other two are dummy

variables. “Physical well-being”, contributing to the

definition of the “Dimension of physical health”, uses

some of the 12 items that make up the SF-12 ques-

tionnaire. The reason was to identify the most signif-

icant scales underlying the conceptual model, which

lead to the creation of the PCS of the SF-12 survey

(Apolone et al., 2005; Gandek et al., 1998). There-

fore, in detail the input variables are conceptually re-

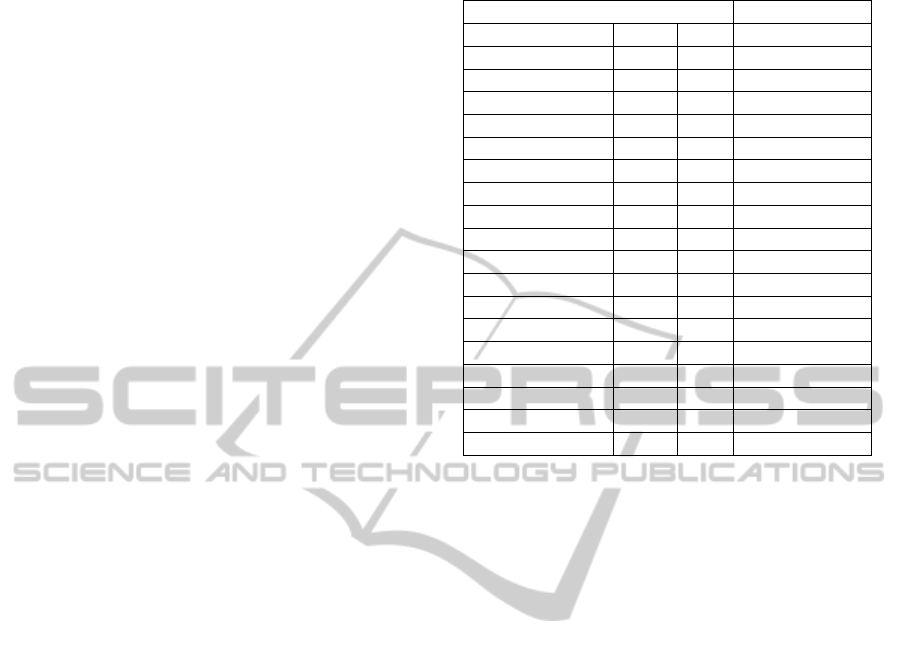

Table 2: A rule-block example:the access to health services.

If Then

Hospitalizations Visits E.R. Health Service

none none No very low

none none Yes low

none some No low

none some Yes low

none many No low

some none No low

none many Yes medium

some none Yes medium

some some No medium

some some Yes medium

some many No medium

many none No medium

some many Yes high

many none Yes high

many some No high

many some Yes high

many many No high

many many Yes very high

lated to the following scales: general health, bodily

pain, physical functioning play their role into the def-

inition of the “Physical well-being” intermediate fac-

tor. This intermediate variable therefore contains the

subjective evaluation of individual general health con-

ditions, given by the interviewee, his perception of

physical limitation due to pain at work and during

usual social activities with family. The other interme-

diate variable taken into account is the “Dimension of

Psychological and Relational Health”, whose purpose

is to evaluate individual health from a psychological-

well being point of view. The dimension of Psycho-

logical and Relational Health is deliberately made up

of many variables relying on the scales that are the

main components of PCS in the SF-12 analysis: vi-

tality, social functioning, emotional role and mental

health. The aggregating process described, through

the use of rule blocks, is iterated from the left to the

right of the system tree. At the end of the process, to

make the results intelligible to human beings it is nec-

essary to de-fuzzify the results. This is done by using

the Center of Maximum method described above.

5 THE INDIVIDUAL HEALTH

STATUS IN ITALY AND THE

ROLE OF OBSERVABLE

CONVERSION FACTORS

In this paragraph we will analyze the results of the

FIS applied to health, trying to place some personal

MEASURING THE CAPABILITY OF LIVING A HEALTHY LIFE WITH FUZZY LOGIC IN A GENDER

PERSPECTIVE

395

or social factors in relationship with the development

of the capability of living a healthy life. The degree

of development will be approximated using the final

output of the FIS presented in the previous paragraph.

The sample for this analysis, as already stated, comes

from the Italian National Institute of Statistics survey

on health for 2004-2005. In particular, the object of

our investigation is the subset of people over 14 who

did not present any missing values on the variables

chosen to run the FIS. In fact, one of the main prereq-

uisites of an FIS is that the data matrix has to be dense.

Since our dataset contains a relatively high number of

observations, this prerequisite can be easily satisfied:

the final sample is made up of 111,151 individuals,

weighted to be significant both at a national and at a

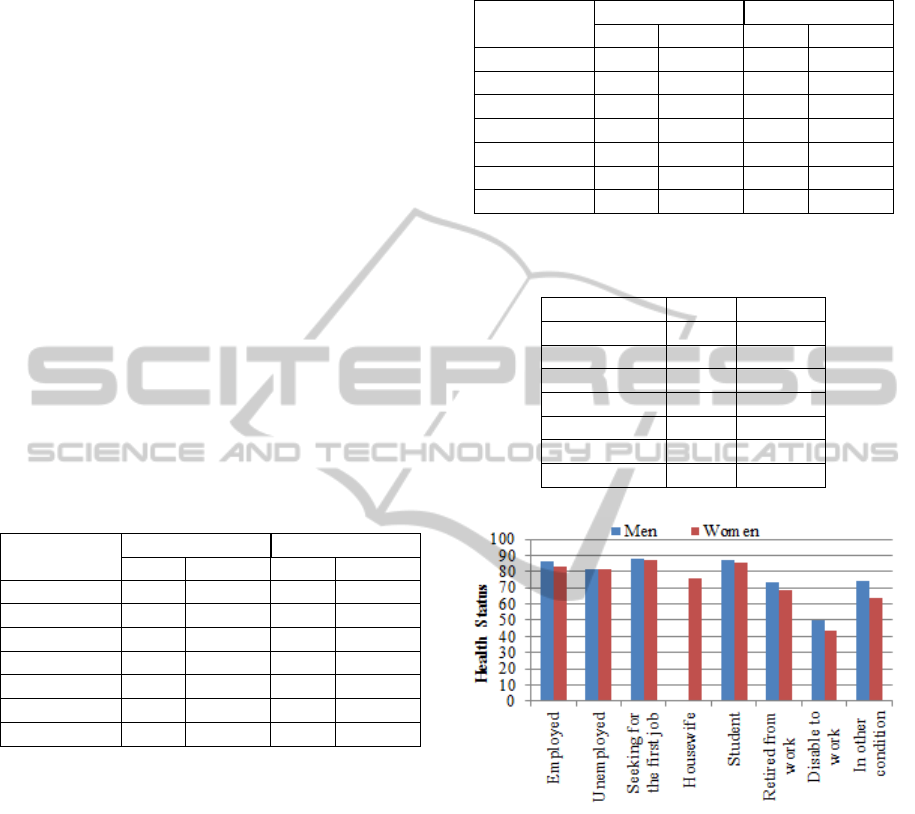

regional level. In Table 3 we compare the results on

the measurement of the two Phsycological Health in-

dicators: the fuzzy DPRH and the SF-12 MCS, while

in Table 4 we compare the results obtained for the two

Physical Health indicators the fuzzy PWB and the SF-

12 PCS. Table 5 contains the results of the Fuzzy final

output value on Health by gender and age.

Table 3: A comparison between the two Psychological

Health indicators: DPRH and MCS.

Age Classes

DPRH MCS

Men Women Men Women

15-24 88.64 84.34 53.70 51.36

25-34 85.56 81.05 52.58 50.52

35-44 82.14 78.34 51.59 49.88

45-54 78.50 72.89 50.81 48.60

55-64 74.21 67.73 50.43 48.03

65-74 68.20 59.99 49.67 46.43

75+ 56.21 47.84 47.16 44.09

Standardizing both the outputs of the evaluation

system on a 0-100 range, we discovered that the fuzzy

indexes are generally higher than MCS and PCS with

respect to all the age classes, for both genders, but it

is also pretty clear that the variability of the fuzzy in-

dexes is much higher; hence the fuzzy outcomes are

more sensitive to the changes caused by age. Further-

more, even though the results are generally higher, the

trends are the same: women’s health is worse than

men’s at every age, with a strong and constant de-

crease over time.

This result is also confirmed by the trend in the

main index (Health Status), which is higher, on av-

erage, among the youngest individuals, a little better

for men than for women, decreasing with age. All the

indexes obtained and analyzed present a similar trend.

If we consider people’s health status and we com-

pare it now with their employment status, we see that

the results are fairly consistent with what we might

Table 4: A comparison between the two Physical Health

indicators: PWB and PCS.

Age Classes

PWB PCS

Men Women Men Women

15-24 92.35 90.60 55.28 55.31

25-34 90.45 87.71 54.52 53.95

35-44 88.19 85.98 53.59 53.12

45-54 85.49 80.93 52.43 51.13

55-64 80.99 74.22 50.38 48.27

65-74 72.97 63.55 46.96 44.10

75+ 55.46 44.23 40.39 36.87

Table 5: The average Health Status index by gender and age

class.

Age Classes Men Women

15-24 87.19 85.13

25-34 88.46 85.87

35-44 85.91 84.02

45-54 83.20 80.02

55-64 79.83 75.79

65-74 74.87 69.48

75+ 65.50 59.61

Figure 4: The average Health Status by gender and employ-

ment status.

expect: students and people seeking their first job are

expected to be younger and they actually receive the

highest marks. On the other hand, we find people who

are retired from work whose health status is worse

given their average higher age.

But if we consider employed and unemployed

people (Figure 4) we see that these two groups, which

apparently should not differ so much as regards their

average age, present quite different marks: 85.95 for

the employed males against 81.62 for the unemployed

and 83.48 for the employed women, compared to

81.48 of the unemployed women. This is in line with

the health costs linked to unemployment status as out-

lined in Sen (1997). Turning to education (Figure 5),

FCTA 2011 - International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

396

Figure 5: The average Health Status by gender and educa-

tional level.

the data confirm what the literature claims as com-

mon ground: a higher educational level is positively

related to individual health. We then completed our

analysis by estimating a multivariate OLS regression

model that allows us to take into account the weight

of the different conversion factors on the index of liv-

ing a healthy life resulting from the implementation

of our FIS model (Table 6) to the data.The results ob-

tained confirm a negative effect of ageing on the fuzzy

measure of health and, having controlled for age, one

can see that women are still characterized by worse

health than men. Health improves when the education

level is higher. Turning to employment conditions, we

may see that controlling for age and education lev-

els, if one holds a temporary work position, his/her

health status deteriorates (the control variable being

employed on a permanent basis). Joblessness is also

consistent with Sen’s analysis (1997) leading to lower

health. Those living in the South of Italy show a lower

level of health achievement, and this is probably con-

nected to worse health infrastructures in the South of

Italy. Deeper analyses on regional variability will be

performed in further research by matching our popu-

lation data with health infrastructures administrative

data.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In the analysis of individual well-being, health status

is a central dimension. In this paper we have analyzed

the individual health status by considering its multidi-

mensional nature. In order not to lose its complexity

we have proposed a modular approach (the fuzzy tree

diagram) which allows us to obtain an index on health

without losing single macro-index information. The

choice, interaction and the effects of the various avail-

able indicators were chosen by the authors on the ba-

Table 6: Health Status: a multivariate analyses (standard

errors in parenthesis).

Variables Health

Age

-0.184***

(0.00186)

Woman

-0.0401***

(0.00142)

Married/Cohabiting

0.0516***

(0.00143)

Diploma

0.0487***

(0.00151)

Degree and more

0.0712***

(0.00237)

Temporary

-0.00978***

(0.00330)

Retired

-0.0772***

(0.00212)

Disable to work

-0.539***

(0.00551)

Other empl. condition

-0.0563***

(0.00178)

Unemployed

-0.0282***

(0.00302)

South

-0.0125***

(0.00139)

Constant

5.060***

(0.00671)

Observations 111.151

R-squared 0.187

sis of health experts’ opinions, expressed through lin-

guistic rules. This methodology reduces the debated

problem of the numerical attribution of weights. The

health status (the final output of our fuzzy inference

system) is determined by the interaction in the FIS

of access to health services, the dimension of mental

health and that of physical health. The first innova-

tive product is thus precisely the use of a fuzzy in-

ference system on the health status since it shows the

individual settlement through the combination of the

observable variables in the survey on the health status

of the Italian population. We then analyzed the crisp

value produced in relation to individual and family

variables which may interact with the very fundation

of a healthy condition. During the construction of the

intermediate variables and of the whole system, the

method that we applied maintains the complexity of

the definition of health status, while at the same time,

is able to produce a synthetic and numeric index. On

average, the health status index of the Italian popu-

lation is found to be lower for women than for men

and for people holding unstable working positions,

without work or living in the South. Further devel-

opments are at two different levels. The first, follow-

MEASURING THE CAPABILITY OF LIVING A HEALTHY LIFE WITH FUZZY LOGIC IN A GENDER

PERSPECTIVE

397

ing Addabbo et alt.(2010a) will be in a local direction,

the analysis will be replicated to a more homogeneous

area (the province of Modena). At national level we

aim to match the survey data on the population with

regional administrative data on the health infrastruc-

tures to allow for a deeper analysis of the impact of

health services on individual health outcomes.The re-

sults of our research on the construction of a new in-

dex of the capability of living a healthy life can then

be transferred - by a researcher from our research unit

- to the Italian Commission on the Definition of the

Quality of Life created in April 2011 by the Italian

National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) and the Na-

tional Centre of Economics and Labour (Cnel) both

because health is a relevant dimension in the construc-

tion of the quality of life, and because of the innova-

tive methodology used for its measurement.

REFERENCES

Addabbo, T., Chiarolanza, A., Fuscaldo, M., and Pirotti, T.

(2010a). Una valutazione estesa del benessere sec-

ondo lapproccio delle capacit

`

a: vivere una vita sana,

chapter 7. In Baldini, M., Bosi, P., and Silvestri, P., ed-

itors, Le citt

`

a incartate, Mutamenti nel modello emil-

iano alle soglie della crisi, Bologna. Il Mulino.

Addabbo, T. and Di Tommaso, M. L. (2008). Children’s ca-

pabilities and family characteristics in Italy. Materiali

di discussione del Dipartimento di Economia Politica,

(590).

Addabbo, T., Di Tommaso, M. L., and Facchinetti, G.

(2004). To what extent fuzzy set theory and structural

equation modelling can measure functionings? An ap-

plication to child well-being. Materiali di Discussione

del Dipartimento di Economia Politica, (468).

Addabbo, T., Facchinetti, G., Maccagnan, A., Mastroleo,

G., and Pirotti, T. (2010b). A fuzzy system to evaluate

how parents interact with their children. In Metody

Informatyki Stosowanej, volume 3/2010.

Addabbo, T., Facchinetti, G., and Mastroleo, G. (2006). Ca-

pability and functionings. a fuzzy way to measure in-

teraction between father and child. In Saeed Khalid,

Pejas, Jerzy, and Mosdorf Romuald, editors, Biomet-

rics, Computer Security Systems and Artificial Intelli-

gence Applications, pages 185–195. Springer Science.

Addabbo, T. and Favaro, D. (2011). Part-time and tempo-

rary employment in a gender perspective, chapter 3.

In Addabbo, T. and Solinas, G., editors, Non standard

employment and quality of work. The case of Italy.

Springer Verlag, forthcoming.

Apolone, G., Mosconi, P., and Ware, J. E. (2005). Ques-

tionario sullo stato di salute SF12. versione italiana.

Milano. Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario

Negri.

Cheli, B. and Lemmi, A. (1995). A “totally” fuzzy and

relative approach to the multidimensional analysis of

poverty. Economic Notes, pages 115–134.

Chiappero Martinetti, E. (2000). A multidimensional as-

sessment of well-being based on Sens functioning ap-

proach. Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali,

2:207–239.

Cole, T. J., Bellizzi, M. C., Flegal, K. M., and Dietz, W. H.

(2000). Establishing a standard definition for child

overweight and obesity worldwide: international sur-

vey. British Medicine Journal, 320(7244):1240–1243.

Di Martino, M. (2008). Le condizioni di salute della popo-

lazione: Un’analisi multilivello delle disuguaglianze

sociali. In XXIX Conferenza Italiana di Scienze Re-

gionali, Bari.

Fleurbaey, M. (2009). Beyond gdp: the quest for a mea-

sure of social welfare. Journal of Economic Litera-

ture, 47(4):1029–1075.

Gandek, B., Ware Jr, J. E., Aaronson, N. K., Apolone, G.,

Bjorner, J. B., Brazier, J. E., Bullinger, M., Kaasa, S.,

Leplege, A., Prieto, L., et al. (1998). Cross-validation

of item selection and scoring for the sf-12 health sur-

vey in nine countries:: Results from the iqola project.

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11):1171–1178.

Kuklys, W. (2003). Measurement and determinants of wel-

fare achievement-evidence. In 3rd Conference on the

Capability Approach, Pavia.

Mackenbach, J. P., Bakker, M. J., et al. (2003). Tackling so-

cioeconomic inequalities in health: analysis of Euro-

pean experiences. The Lancet, 362(9393):1409–1414.

Pirotti, T. (2006). Le dimensioni del benessere: la salute.

misure sfocate nellapproccio delle capacit

`

a. Master’s

thesis, Universit

`

a di Modena e Reggio Emilia.

Sen, A. K. (1993). Capability and well-being. In Nuss-

baum, M. and Sen, A. K., editors, The Quality of Life,

Oxford. Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. K. (1997). Inequality, unemployment and contem-

porary europe. Int’l Lab. Rev., 136:155.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A. K., Fitoussi, J. P., et al. (2009). Re-

port by the commission on the measurement of eco-

nomic performance and social progress. Commission

on the Measurement of Economic Performance and

Social Progress, Paris.

United Nations Development Programmes (1990). Human

development report 1990: Concept and measurement

of human development. In UNDP, New York Oxford.

Oxford University Press.

Wagstaff, A., Paci, P., and Van Doorslaer, E. (1991). On the

measurement of inequalities in health. Social Science

& Medicine, 33(5):545–557.

Ware Jr, J. E., Kosinski, M., and Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-

item short-form health survey: construction of scales

and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medi-

cal care, 34(3):220.

Ware Jr, J. E., Kosinski, M., Keller, S. D., and Institute, N.

E. M. C. H. (1998). Sf-12: How to score the sf-12

physical and mental health summary scales.

Ware Jr, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., and Gandek, B.

(1993). SF-36 health survey: manual and interpreta-

tion guide. The Health Institute, New England Medi-

cal Center.

FCTA 2011 - International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

398