DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS MODELLING METHOD

L. O. Meertens, M. E. Iacob and L. J. M. Nieuwenhuis

University of Twente, PO Box 217, Enschede, The Netherlands

{l.o.meertens, m.e.iacob, l.j.m.nieuwenhuis}@utwente.nl

Keywords: Business modelling, Modelling method, Business models.

Abstract: Currently, business modelling is an art, instead of a science, as no scientific method for business modelling

exists. This, and the lack of using business models altogether, causes many projects to end after the pilot

stage, unable to fulfil their apparent promise. We propose a structured method to create “as-is” business

models in a repeatable manner. The method consists of the following steps: identify the involved roles,

recognize relations among roles, specify the main activities, and quantify using realistic estimates of the

model. The resulting business model is suitable for analysis of the current situation. This is the basis for

further predictions, for example business cases, scenarios, and alternative innovations. We offer two extra

steps to develop these innovations and analyse alternatives. Using them may enable successful projects to be

implemented, instead of ending on a shelf after the pilot stage.

1 INTRODUCTION: BUSINESS

MODELLING BACKGROUND

A business model is critical for any company, and

especially for any e-business. Its importance has

been recognized over the past few years by several

authors that have created different business model

frameworks aimed at identifying the main

ingredients of a business model (for example,

Osterwalder (2004); for an overview, see Pateli &

Giaglis (2004), and Vermolen (2010)). However, the

state in which this field finds itself is one of

“prescientific chaos” (Kuhn 1970): there are several

competing schools of thought, and progress is

limited because of a lack of cumulative progress.

Because of this, there are no clear and unique

semantics in the research related to business models.

The very concept of “business model” is associated

with many different definitions (Vermolen 2010).

The elements of such a business model differ

significantly from one approach to another.

Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there are

no methodological approaches in the literature for

the design and specification of business models

(Vermolen 2010). This lack of cohesion in the field

clearly diminishes the added value of business

models for companies and makes business

modelling an art, rather than a science. This state of

affairs motivated us to propose such a method,

which enables the development of business models

in a structured and repeatable manner. Thus the

contribution of this paper is three-fold:

A business model development method;

A definition of the concept of business model and

the identification of its core elements, captured by

the deliverables of the method steps;

An illustration of the method by means of a case

study from the healthcare domain.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 focuses

on the discussion of the main concepts addressed in

the paper, and positions our approach with respect to

the existing design science and method engineering

literature. In Section 3, we describe the steps of our

business model development method. In Section 4,

we demonstrate the method by means of a case study

concerning the development of a qualitative business

model of the elderly care in The Netherlands.

Finally, we conclude our paper and give pointers to

future work in Section 5.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

A simple analysis of the two words “business

model” already gives an idea of what a business

model is about. On the one hand, there is “business”:

the way a company does business or creates value.

On the other hand, there is “model”: a

88

Meertens L., Iacob M. and Nieuwenhuis B.

DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS MODELLING METHOD.

DOI: 10.5220/0004458900880095

In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2011), pages 88-95

ISBN: 978-989-8425-68-3

Copyright

c

2011 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

conceptualization of something – in this case, of

how a company does business.

We extend this common and simplistic

interpretation of a business model as “the way a

company earns money”, into a broader and more

general definition of the concept: “a simplified

representation that accounts for the known and

inferred properties of the business or industry as a

whole, which may be used to study its characteristics

further, for example, to support calculations,

predictions, and business transformation.”

The last part of the definition above, namely the

indication of the possible uses of a business model is

of particular importance in the context of this paper.

The method we propose not only facilitates the

development of such a design artefact - a business

model - but also takes a business engineering

perspective. Thus, its application will result in two

(or more) business models: one that reflects the “as-

is” situation of the business and one or more

alternative “to-be” business models that represents

possible modifications of the business as result of,

for example, adoption of innovative technologies or

more efficient business processes.

To the best of our knowledge, such a method

does not exist yet for what we define as business

models (Vermolen 2010). In the remainder of this

section, we position our work in the contexts of

design science and method engineering, to which it

is related.

2.1 Design Science

A business modelling method can be seen as a

design-science artefact. It is the process of creating a

product: the business model. We use the seven

guidelines of Hevner et al. (2004) to frame how we

use the methodology engineering approach from

Kumar & Welke (1992) to create our method.

The first guideline advises to design as an

artefact. Design-science research must produce a

viable artefact in the form of a construct, a model, a

method, or an instantiation. As said, we produce a

method.

The second guideline tackles relevance. The

objective of design-science research is to develop

technology-based solutions to important and relevant

business problems. Viable business models lie at the

heart of business problems. However, our solution is

not yet technology-based. Partial automation of the

method is left for future research.

The utility, quality, and efficacy of a design

artefact must be rigorously demonstrated via well-

executed evaluation methods. We demonstrate the

business modelling method using a case study. We

leave more rigorous evaluation for further research.

Research contribution is the topic of the fourth

guideline. Effective design-science research must

provide clear and verifiable contributions in the

areas of the design artefact, design foundations,

and/or design methodologies. We provide a new

artefact to use and study for the academic world.

The methodology may be extended, improved, and

specialized.

Guideline five expresses the scientific rigour:

Design-science research relies upon the application

of rigorous methods in both the construction and

evaluation of the design artefact. We aim to be

rigorous through using the methodology engineering

approach. Existing, proven methods are used as

foundation and methods where applicable.

Evaluation was handled in the third guideline.

The sixth guideline positions design as a search

process. The search for an effective artefact requires

utilizing available means to reach desired ends while

satisfying laws in the problem environment.

Whenever possible, we use available methods for

each of the steps. Following the methodology

engineering approach helps us to satisfy the laws for

creating a new methodology.

The final guideline instructs us to communicate

our research. Design-science research must be

presented effectively both to technology-oriented as

well as management-oriented audiences. This article

is one of the outlets where we present our research.

2.2 Methodology Engineering

Methodologies serve as a guarantor to achieve a

specific outcome. In our case, this outcome is a

consistent and better-informed business model. We

aim to understand (and improve) how business

models are created. With this understanding, one can

explain the way business models help solve

problems. We provide a baseline methodology only,

with a limited amount of concepts. Later, we can

extend, improve and tailor the methodology to

specific situations or specific business model

frameworks.

The business modelling method has both aspects

from the methodology engineering viewpoint:

representational and procedural (Kumar & Welke

1992). The representational aspect explains what

artefacts a business modeller looks at. The artefacts

are the input and deliverables of steps in the method.

The procedural aspect shows how these are created

and used. This includes the activities in each step,

tools or techniques, and the sequence of steps.

DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS MODELLING METHOD

89

3 DEFINING THE BUSINESS

MODELLING METHOD

We define five individual step of business

modelling, which the rest of this section elaborates.

To describe each step, we use the following

elements:

inputs of the step,

activities to perform during the step,

possible techniques to use during the step’s

activities, and

deliverables resulting from the step.

Each step in the proposed method requires specific

methods, techniques or tools that are suitable for

realizing the deliverables. We will mention

examples of those. However, others may also be

useful and applicable, and it is not our aim to be

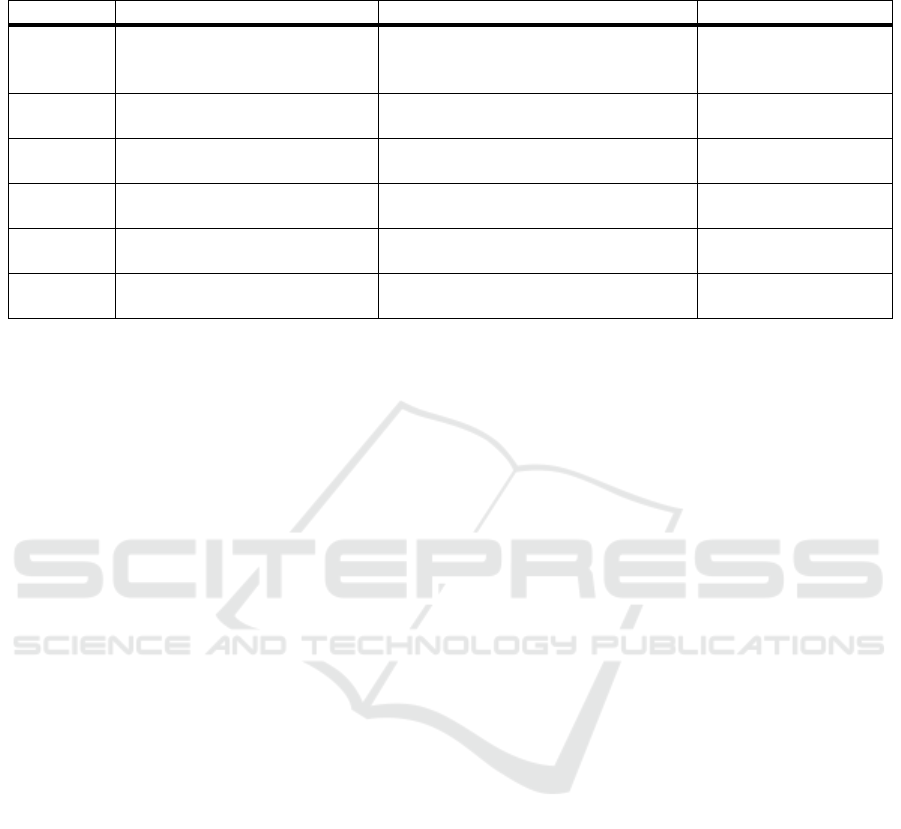

exhaustive in this respect. Table 1 shows an

overview of our method.

3.1 Create As-Is Model

As mentioned in the previous section, our business

model development method takes business

engineering perspective. Thus, the first four steps of

our method focus on creating a business model that

reflects the current state of the business. Therefore,

steps one through four create an as-is model.

3.1.1 Step 1: Identify Roles

Identifying the relevant parties (which we refer to as

roles) involved in a business model should be done

as systematically as possible. The aim is

completeness in this case. The business modeller

must carry out a stakeholder analysis, to identify all

roles. The input to this step includes for example,

documentation, domain literature, interviews,

experience and previous research. The output is a list

of roles.

For an example of stakeholder analysis method,

we refer to Pouloudi & Whitley (1997). They

provide an interpretive research method for

stakeholder analysis aimed at inter-organizational

systems, such as most systems where business

modelling is useful. The method consists of the

following steps:

1. Identify obvious groups of stakeholders.

2. Contact representatives from these groups.

3. (In-depth) interview them.

4. Revise stakeholder map.

5. Repeat steps two to four, until...

Pouloudi and Whitley do not list the fifth step,

but mention that stakeholder analysis is a cumulative

and iterative approach. This may cause the number

of stakeholders to grow exponentially, and the

question remains when to stop. Lack of resources

may be the reason to stop the iterative process at

some point. Closure would be good, but seems hard

to achieve when the model is more complex.

Probably, the modeller has to make an arbitrary

decision. Nevertheless, one should choose stop

criteria (a quantifiable measure of the stakeholder’s

relevance for the respective business model and a

threshold for the measure) before starting the

process (Pouloudi 1998).

“Revising the stakeholder map” (step four) could

use extra explanation, which can be found in the

description of the case Pouloudi and Whitley use to

explain the method. The stakeholders gathered from

interviews can be complemented with information

found in the literature. The business modeller then

refines the list of stakeholders by focussing,

aggregating, and categorizing.

3.1.2 Step 2: Recognize Relations

The second step of our method aims to discover the

relations among roles. The nature of these relations

may vary substantially, but it always involves some

interaction between the two roles and may assume

some exchange of value of some kind. Much of the

work and results from the previous step can be

reused for this as input. In theory, all roles could

have relations with all other roles. However, in

practice, most roles only have relations with a

limited number of other roles. Usually, these

relations are captured in a stakeholder map, which

often follows a hub-and-spoke pattern, as the focus

is on one of the roles. This pattern may be inherent

to the approach used, for example if the scope is

defined as a maximum distance from the focal role.

To specify all relations, we suggest the use of a

role-relation matrix with all roles on both axes as

technique. Of this matrix, the cells point out all

possible relations among the roles. Each of the cells

could hold one or more relations between two roles.

Assuming that roles have a limited number of

relations, the role-relation matrix will be partially

empty. However, one can question for each empty

cell whether a relation is missing or not.

Cells above and below the diagonal can represent

the directional character of relations. Usually,

relations have a providing and consuming part. The

providing part goes in the upper half of the matrix,

and the consuming part in the bottom half. This

BMSD 2011 - First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

90

Table 1: Business Modelling Method.

Step Inputs Techniques or Tools Deliverables

Identify

Roles

Documentation, domain literature,

interviews, experience, previous

research

Stakeholder analysis (Pouloudi & Whitley

1997)

Role list

Recognize

Relations

Role list, Stakeholder map, value

exchanges

e3-value (Gordijn 2002) Role-relation matrix

Specify

Activities

Role-relation matrix, Role list,

business process specifications

BPM methods, languages and tools List of activities

Quantify

Model

Process specifications, accounting

systems and annual reports

Activity based costing Total cost of the business

“as-is”

Design

Alternatives

As-is business model, Ideas for

innovations and changes

Business modelling method (steps 1 to 4),

Brainstorming

One or more alternative

business models

Analyse

Alternatives

Alternative business models Sensitivity analysis, technology assessment,

interpolation, best/worst case scenarios

Business case for each

alternative

especially helps with constructions that are more

complex, such as loops including more than two

roles.

The output of this step is a set of relations.

3.1.3 Step 3: Specify Activities

For a first qualitative specification of the business

model, the next step is to determine the main

activities. Relations alone are not sufficient: the

qualitative model consists of these main business

activities (business processes) too. These activities

originate from the relations identified in the previous

step. Each of the relations in the role-relation matrix

consists of at least one interaction between two

roles, requiring activities by both roles. Besides

work and results from the previous steps, existing

process descriptions can be valuable input.

Techniques from business process management may

be used.

The output from these first three steps is a first

qualitative business model, including roles, relations

and activities. It reveals what must happen for the

business to function properly.

3.1.4 Step 4: Quantify Model

Quantifying the business model helps us to see what

is happening in more detail and compare innovations

to the current situation. To turn the qualitative model

into a quantitative model, numbers are needed. The

numbers are cost and volume of activities (how

often they occur). Together, these numbers form a

complete view of the costs captured by the business

model.

Several sources for costs and volumes are

possible, such as accessing accounting systems or

(annual) reports. The resulting quantitative business

model shows the as-is situation.

3.2 Develop To-Be Model

The as-is model, created in previous steps, is

suitable for analysis of the current state only.

However, from the as-is model, it is possible to

derive alternatives. Such alternatives can be created

to assess how reorganisations, innovations or other

changes influence the business. These are the to-be

models.

3.2.1 Step 5: Design Alternatives

From here on, we aim to capture a future state of the

business in a business model. To make predictions,

the model may need further instantiations. Each

instantiation is an alternative development that may

happen (to-be). Using techniques such as

brainstorming and generating scenarios, business

modellers create alternative, qualitative, future

business models. These alternatives are used to

make predictions. Usually, such alternatives are built

around a (technical) innovation. This may include

allocating specific roles to various stakeholders. A

base alternative, which only continues an existing

trend without interventions, may help comparing the

innovations. Next to the business model, ideas for

innovations serve as input. The resulting alternative

business models show future (to-be) possibilities.

3.2.2 Step 6: Analyse Alternatives

The final step for a business modeller is to analyse

the alternative business models. Besides the

qualitative business models, several sources of input

DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS MODELLING METHOD

91

are possible to quantify the alternatives. Applicable

techniques include sensitivity analysis, technology

assessment, interpolation and using best/worst case

scenarios. Each alternative can be tested against

several scenarios, in which factors change that are

not controllable. We can use the models to predict

the impact. This step and the previous one can be

repeated several times to achieve the best results.

The final output is a business case (including

expected loss or profit) for each alternative.

4 THE U*CARE CASE:

DEMONSTRATING THE

BUSINESS MODELLING

METHOD

U*Care is a project aimed at developing an

integrated (software) service platform for elderly

care (U*Care Project n.d.). Due to the aging

population and subsequently increasing costs,

elderly care - and healthcare in general - is one of

the areas where governments fund research.

However, many projects never get further than pilot

testing. Even if the pilot is successful, the report

often ends on a shelf. By applying the business

modelling method, we plan to avoid this and put the

U*Care platform into practice. Specifically, we aim

to show how the technological innovations built in

the U*Care platform will influence the business

model for elderly care.

The U*Care case is in progress currently, and

therefore, it is suitable for demonstrating the first

three steps of the business modelling method. These

three steps result in a qualitative business model of

the as-is situation of the elderly care. At this time,

we are collecting quantitative data. Therefore, steps

four to six of the method are not yet possible and we

will not address them here. However, they will be

subject of future work.

4.1 Identify Roles

The first step of the stakeholder analysis, led to the

identification of several groups of obvious

stakeholders. The groups include all the project

partners, as their participation in the project

indicates their stake. Another group includes the

main users of the platform: the clients and

employees of the elderly care centre.

After identifying the obvious stakeholders, we

contacted and interviewed representatives from all

the project partners and several people in the care

centre. These interviews did not explicitly focus on

stakeholder analysis, but served as a general step in

requirements engineering.

Table 2 displays a partial

list of identified stakeholders after steps two and

three of Pouloudi and Whitley’s method for

stakeholder analysis have been performed.

Table 2: Partial list of stakeholders after step three of

Pouloudi and Whitley's method for stakeholder analysis.

Clients Care (& wellness) providers

Volunteer aid Hospitals

Nurses Elderly care centres

Doctors Psychiatric healthcare

Administrative employees Homecare

General practitioners Technology providers

Federal government User organizations

Local government Insurance companies

The fourth step includes a search for

stakeholders in the literature. Besides identifying the

extra stakeholders, the literature mentioned the

important issue that some actors in the list are

individual players, while other actors are

organizations or other forms of aggregations

(groups). Consequently, overlap can occur in the list

of actors.

The final action of the first iteration is not a

trivial one. Refining the stakeholder list requires

interpretation from the researcher. Different

stakeholder theories (for example, E. J. Emanuel &

L. L. Emanuel (1996), J. Robertson & S. Robertson

(2000), and Wolper (2004)) act as tools to minimize

subjectivity.

The long list of identified stakeholders is not

practical to continue with and has much overlap.

Therefore, we grouped the stakeholders into a

limited set of roles, shown in

Table 3. This set of

high-level roles is an interpretive choice. The small

set helps to keep the rest of case clear instead of

overcrowded. The larger set is kept in mind for the

to-be situation to find potential “snail darters”:

stakeholders with only a small chance of upsetting a

plan for the worse, but with huge results if they do

(Mason & Mitroff 1981). The small set of

stakeholders was subject to prioritization based on

Mitchell et al. (1997). While the prioritization is

subjective, it shows that all roles in the list are

important.

4.2 Recognize Relations

The current situation consists of five categories of

interacting roles. Table 3 shows them on both axes.

The cells show relations between the roles. While

BMSD 2011 - First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

92

Table 3: Role-relation matrix.

Consumer

Provider

Care consumers Care providers Technology

providers

Government Insurers

Care consumers X

Pay for care

Pay for AWBZ

Pay for WMO

Pay for

insurance

Care providers Provide ZVW care

Provide WMO care

Provide AWBZ care

X Pay for (use of)

technology or

service

Provide care to

citizens

Provide care

to insured

Technology

providers

Provide technology

or service

X

Government Provide AWBZ

insurance

Provide WMO

insurance

Pay for WMO care

to citizens

X Pay for

AWBZ care to

citizens

Insurers Provide insurance

Refund AWBZ and

ZVW care

Ensure AWBZ care

for citizens

X

the care provider has relations with all the other

roles, it is not a clear hub-and-spoke pattern. Several

of the other roles have relations outside the care

provider.

The relations show that a main goal of the

business is to provide care to the care consumer. The

insurers and government handle much of the

payment. Other (regulating) roles of the government

remain out of scope, as the case is complex enough

as it is.

The insurers handle most of the payments. The

patient has to pay the care provider after receiving

care. The patient can then declare the costs to the

insurance company, which refunds the patient. The

patient pays a premium to the insurance company.

According to the Dutch Healthcare Insurance Act

(Zorgverzekeringswet, ZVW), every citizen has to

have basic care insurance (ZVW). For “uninsurable

care” (including most home healthcare, similar to

USA Medicare), the Dutch government set up a

social insurance fund, termed General Exceptional

Medical Expenses Act (Algemene Wet Bijzondere

Ziektekosten, AWBZ). All employees and their

employers contribute towards this fund. The AWBZ

is similar to the regular insurance companies, except

for collecting the premium. The premium is paid

through taxation by the government, which

outsources most of the further actions to insurers. A

similar system is set up for wellness homecare, such

as cleaning. This is the Social Support Act (Wet

Maatschappelijke Ondersteuning, WMO). In

contrast to the AWBZ, the government takes care of

all actions itself, through its municipalities.

Several issues exist, which we do not handle in

detail here. For example, it is inherent to insurance

that not all people who pay premium are also

(currently) care consumers.

4.3 Determine Behaviour

Most of the relations between the roles in Table 3

start with verbs. This signals that they are (part of)

behaviour. Any relation not beginning with a verb is

a candidate for rephrasing or being split into smaller

parts.

Besides the relations, we focussed on AWBZ to

identify the main activities of the care providers.

“Providing care” has four top-level functions:

personal care, nursing, guidance/assistance, and

accommodation. Each of these functions consists of

many detailed activities, of which Table 4 provides

an example.

We obtained these activities from documents

made available by the government for

reimbursement purposes (Ministry of Health,

Welfare and Sport 2008). As it also provides an

indication of volume (times a day) and a first

indication of costs (minutes spent), it is a first step

towards quantifying the model.

4.4 Further Steps

The other three steps are not possible for now, as

detailed quantitative data is not available yet.

However, when we have developed a quantitative

business model, the final steps of the method help to

generate business cases easily for various services

that could be integrated into the U*Care platform.

This should proof their viability and lead to

implementation, instead of ending on the shelf.

DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS MODELLING METHOD

93

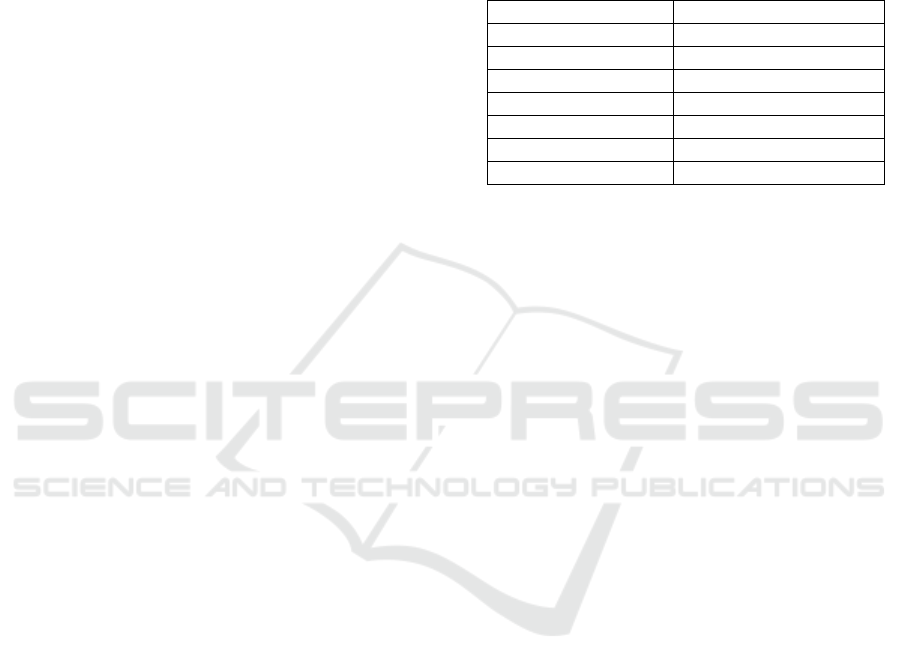

Table 4: Example of personal care activities.

Activity Actions Time in

minutes

Frequency

per day

Washing Whole body

Parts of body

10

20

1x

1x

Dressing (Un)dress completely

Undress partially

Dress partially

Put on compression stockings

Take off compression stockings

15

10

10

10

7

2x

1x

1x

1x

1x

Getting in and out of bed Help getting out of bed

Help getting into bed

Help with afternoon rest (for example, get onto the couch)

Help with afternoon rest (for example, get off the couch)

10

10

10

10

1x

1x

1x

1x

Eating and drinking Help with eating cold meals (excluding drinking)

Help with eating warm meal (excluding drinking)

Help with drinking

10

15

10

2x

1x

6x

5 CONCLUSIONS: A FUTURE

FOR BUSINESS MODELLING

Three contributions are made in this paper.

Primarily, we created a business model development

method. Secondly, we defined the concept of

business model and identified its core elements,

captured by the deliverables of the method steps.

Finally, we demonstrated the method by means of a

case study from the healthcare domain.

The business modelling method provides a way

to create business models. Innovators can apply the

steps to create business cases for their ideas

systematically. This helps them to show the viability

and get things implemented.

We provide a new design-science artefact to use

and study for the academic world. As business

modelling has several goals, conducting only the

first few steps may be enough. For example, if your

goal is to achieve insight in the current state only,

the last two steps are not useful.

The business modelling method may be

extended. Situational method engineering seems

suitable for this (Henderson-Sellers & Ralyté 2010).

For example, for information system development, it

is interesting to research if steps towards enterprise

architecture can be made from business models. This

can be seen as a higher-level form of, or preceding

step to, the BMM proposed by Montilva and Barrios

(2004). On the other side, a step could be added

before identifying roles. Other domains require

different improvements.

In addition, the steps in the method can be

further specified. The steps can be detailed further.

One of the ways to do this is to tailor the techniques

at each of the steps of this method. In the future, new

tools and techniques may help provide partial

automation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of the IOP GenCom U-CARE

project, which the Dutch Ministry of Economic

Affairs sponsors under contract IGC0816.

REFERENCES

Emanuel, E. J. & Emanuel, L. L., 1996. What is

Accountability in Health Care? Annals of Internal

Medicine, 124, pp.229-239.

Gordijn, J., 2002. Value-based Requirements Engineering:

Exploring Innovative e-Commerce Ideas. PhD Thesis.

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Henderson-Sellers, B. & Ralyté, J., 2010. Situational

Method Engineering: State-of-the-Art Review.

Journal of Universal Computer Science, 16(3),

pp.424-478.

Hevner, A. R. et al., 2004. Design Science in Information

Systems Research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1), pp.75-105.

Kuhn, T. S., 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,

University of Chicago Press.

Kumar, K. & Welke, R. J., 1992. Methodology

Engineering: a proposal for situation-specific

methodology construction. In Challenges and

BMSD 2011 - First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

94

Strategies for Research in Systems Development. John

Wiley series in information systems. Chichester:

Wiley, p. 257–269.

Mason, R. O. & Mitroff, I. I., 1981. Challenging strategic

planning assumptions : theory, cases, and techniques,

Wiley.

Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2008.

Beleidsregels indicatiestelling AWBZ 2009.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R. & Wood, D. J., 1997. Toward

a theory of stakeholder identification and salience:

Defining the principle of who and what really counts.

Academy of management review, pp.853-886.

Montilva, J. C. & Barrios, J. A., 2004. BMM: A Business

Modeling Method for Information Systems

Development. CLEI Electronic Journal, 7(2).

Osterwalder, A., 2004. The Business Model Ontology - a

proposition in a design science approach. PhD Thesis.

Universite de Lausanne.

Pateli, A. G. & Giaglis, G. M., 2004. A research

framework for analysing eBusiness models. European

Journal of Information Systems, 13(4), pp.302-314.

Pouloudi, A., 1998. Stakeholder Analysis for

Interorganisational Information Systems in

Healthcare. PhD Thesis. London School of

Economics and Political Science.

Pouloudi, A. & Whitley, E. A., 1997. Stakeholder

identification in inter-organizational systems: gaining

insights for drug use management systems. European

Journal of Information Systems, 6, p.1–14.

Robertson, J. & Robertson, S., 2000. Volere:

Requirements specification template, Technical Report

Edition 6.1, Atlantic Systems Guild.

U*Care Project, U*Care website. Available at:

http://www.utwente.nl/ewi/ucare/ [Accessed May 2,

2011].

Vermolen, R., 2010. Reflecting on IS Business Model

Research: Current Gaps and Future Directions. In

Proceedings of the 13th Twente Student Conference on

IT. Twente Student Conference on IT. Enschede,

Netherlands: University of Twente.

Wolper, L. F., 2004. Health care administration:

planning, implementing, and managing organized

delivery systems, Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS MODELLING METHOD

95