MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY BROWSERS

How Usable are them for Describing Clinical Archetypes?

Jesús Cáceres Tello

1

, Miguel-Angel Sicilia

2

, Adolfo Muñoz Carrero

1

Carlos Rodriguez-Solano Nuzzi

2

and Juan-José Sicilia

3

1

Carlos III Health Institute, Telemedicine and e-Health Research Area, Madrid, Spain

2

Department of Computer Science, University of Alcalá, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain

3

Department of Internal Medicine, Henares Hospital, Coslada, Madrid, Spain

Keywords: SNOMED CT, Archetypes, Usability.

Abstract: Clinical terminologies are a major concern in medical informatics, as they are key to provide medical

systems with higher levels of interoperability. Large terminologies as SNOMED CT are gaining presence in

practical applications. In a related but different direction, archetypes or data type templates are becoming

widespread as interchange mechanisms for medical information. Archetypes support mapping to

terminologies, in a process that is typically done by the experts developing or revising the archetype. It has

been argued that terminology browsers are not appropriate for the task of helping clinical experts in the

mapping process. This paper reports usability studies on two widely used SNOMED CT browsers when

used as tools for mapping archetypes.

1 INTRODUCTION

The archetype formalism has been proposed for the

specification of models of electronic healthcare

records as a means of achieving interoperability

between systems. Archetype-based systems have

attracted an increasing attention as a relevant

technology for the interoperability of heterogeneous

systems (Wollersheim et al., 2009). However, some

sort of mapping of archetype data elements with

shared terminologies is required to guarantee a level

of common semantics across archetypes and also

with existing clinical systems. SNOMED CT

(Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical

Terms) is a large-scale comprehensive clinical

healthcare terminology that is gaining widespread

use and can be used for that binding.

The mapping process of archetypes with

SNOMED terms consists essentially on associating a

data element identified according to the formal

Archetype Description Language (ADL) to a

SNOMED element or expression.

These difficulties include the following:

Experts need to decide on the archetype elements

to be mapped; due to the hierarchical nature of

archetype expressions.

SNOMED CT represents different kinds of

entities, and often a lexical matching is not enough

to provide a correct mapping, as there is a need to

understand the hierarchy to which the term belongs

and the kind of entity that the archetype author

intended to capture.

In many cases, the concrete entities are not

directly available in SNOMED CT as concepts, but

they can be expressed through coordinated post-

coordinated expressions, which use a combination of

two or more concepts combined with qualifiers. The

use of post-coordinated expressions is justified since

SNOMED CT does not cover all potential clinical

concepts and ideas explicitly, as this would be

practically unfeasible. For example, "emergency

appendectomy" can be expressed by combining the

concepts "appendectomy" and "urgency" that are

included in SNOMED CT by the expression:

"80146002|apendiceptomía|:260870009|prioridad|=1

03391001|urgente|"

However, the language for using those expressions

requires some training beforehand for the experts to

master it.

This paper presents an initial exploratory study

to gather insights on the usability of SNOMED

browsers for the particular task of archetype

413

Cáceres Tello J., Sicilia M., Muñoz Carrero A., Rodriguez-Solano Nuzzi C. and Sicilia J..

MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY BROWSERS - How Usable are them for Describing Clinical Archetypes?.

DOI: 10.5220/0003789304130418

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2012), pages 413-418

ISBN: 978-989-8425-88-1

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

mapping. The aim of this research is obtaining

insights that can be used as input for devising

integrated SNOMED-archetype editors or browsers

for doing the mapping.

There is an increasing number of SNOMED

browsers available, either commercial or free. And

they differ significantly in the way of searching

elements and presenting the structure of

relationships inside SNOMED to users. Rogers and

Bodenreider (2008) inspected 17 different browsers

out of 23 identified and extracted a common set of

characteristics. For this study, Minnow and

CliniClue were selected due to their free availability

and the fact that they are complementary in the ways

they structure search interfaces (graphical in the first

case and text-based in the second).

The guiding exploratory hypotheses of the

present study are the following:

Are SNOMED browsers usable for supporting

the task of archetype mapping?

How are SNOMED browser users approaching

the search and navigation process for the concrete

task of searching for terms mapping particular

archetype entities?

It should be noted that the cognitive task required for

mapping an archetype term requires an

understanding of the context of the archetype

element selected, and this in turn requires

understanding the position of SNOMED terms

inside the taxonomy.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides background information on the

archetype approach and the role of terminology

mappings in providing semantics to archetypes,

along with a review on studies related to the

usability of SNOMED or similar tools. Then, the

methods for the exploratory study are described in

Section 3. Results and discussion are provided in

Section 4 and finally, Section 5 is devoted to

conclusions and outlook.

2 BACKGROUND

The archetype approach to the interoperability of

healthcare systems is based on the notion of “two-

level” modelling (Beale, 2002).

This concept is centred in the idea of obtaining a

complete ontological separation between the

information model and the model of knowledge. On

the one hand data from standards such as UNE-EN

ISO13606 or terminology databases of different

nature as SNOMED CT or LOINC, and on the other

hand, the knowledge generated by this information

in healthcare.

Using the UNE-EN ISO13606 we can see that

the information object per excellence in the norm is

called “extract” while the knowledge is represented

by the model of archetypes (Muñoz et al., 2007).

The challenge to achieve interoperability in this

sense is able to represent all possible data structures

properly, in terms of health records are concerned. A

feature in this context is the variability and

complexity of clinical data sets, templates and

ultimately in the way of representing data. The

archetypes emerge as a possible formal definition of

possible compositions of model components for

each clinical service. In this sense, an specific

archetype or restricts the hierarchy of subclasses of a

record component within a larger structure such as

the extract defines names, optionality, cardinality,

data types and ranges and even defaults for some of

its components.

3 METHODS

This study was carried out in response to three

specific objectives:

a. Developing a usability study of each of the tools

proposed

b. Gather feedback on usability using the thinking

aloud protocol.

c. Getting feedback on the feasibility of using

SNOMED CT browsers by professionals for the task

of defining archetype mappings.

A questionnaire was used to collect satisfaction

feedback from the users together with basic data of

the participants, relating not only to their profile,

including nationality, sex or year of birth, and career

and background facts. In this context, potential users

have different profiles, e.g. primary care doctors,

hospital doctors, nurses, pharmacists or documentary

staff. Previous experience with medical terminology

was not considered, as the study is aiming at

exploring the use of the tools for people not having a

specific training on medical terminologies.

The study evaluated the usability of the two

applications by the participants. Usability is an

important aspect of any software. Factors such as

ease of installation or further learning and use are

very important indicators when assessing the quality

of a particular software application. In this sense we

analysed different types of questionnaires, including

SUS (Brooke, 1996), QUIS (Harper and Norman,

1993), CSUQ (JR Lewis, 1995) and SUMI (van

HEALTHINF 2012 - International Conference on Health Informatics

414

Veenendaal, 1998). Finally, it was decided to

conduct the study using the SUMI questionnaire

(Software Usability Measurement Inventory). This

type of questionnaires was developed by the Human

Factors Research Group (HFRG), University

College Cork, in 1986 and allow complementing the

evaluation of usability with the perceptions and

attitudes of users, resulting in reliable indicators in

five key areas (Kirakowski and Corbett, 1993),

namely Efficiency, Affect, Helpfulness, Control and

Learnability.

The experience study consisted of the search of

SNOMED codes for the users to identify both the

archetypes and also the data fields contained in

them. In this sense, a first methodological issue was

that of the source of the archetypes. The CKM

repository maintained by the OpenEHR foundation

was used, as it is the more mature platform and it is

also open and not restricted to some particular

institution’s viewpoint. Another reason for choosing

the repository maintained by the openEHR was that

the archetype language of OpenEHR includes five

kinds of entities that come from ontological analysis

(Beale and Heard, 2007), namely Observation,

Evaluation, Instruction, Action and Administrative.

They are representing different types of care entries,

and may be hypothesized to bring different

requirements for the mappings.

In order to make the test short for a single

session, it was decided to choose only two of the

aforementioned archetypes kinds. With this premise,

the selected were “observation” (concretely, the

indirect_oximetry.v1 archetype) and “action”

(concretely, the medication.v1 archetype)

archetypes, considered as the most important types

of archetypes to carry out the study. To increase the

reliability of the study, different combinations of

archetypes and software used were used for the

different users as shown in Table 1.

These combinations covered all possible options

to prevent order biases in the results. The sequence

began again with user number nine.

In addition to the SUMI questionnaire and the

recording of the sessions using screen recording

software, a "thinking aloud" protocol (Lewis, 1982)

was used during the execution of a task (concurrent)

following the indications by (Ericsson and Simon,

1993).

The study was limited to free browsers having at

least the core SNOMED CT data browsing features

identified by Rogers and Bodenreider (2008). After

a review of existing free ones, the selection resulted

in CliniClue and Minnow.

Table 1: Distribution of tasks among the participants in the

study.

Users

Archetypes Software

Observ. Action CliniClue Minnow

1

x x

x x

2

x x

x x

3

x x

x x

4

x x

x x

5

x x

x x

6

x x

x x

7

x x

x x

8

x x

x x

CliniClue browser was found by Elhanan et al.

(2010) the most popular tool used to access SCT

(54%, exceeds 100%), as well as the most preferred

one (29%). In contrast, Minnow is a relatively new

browser. Minnow was selected due to their wide

differences in response time (as they are using

Lucene indexes inside) and the use of more agile

hierarchical browsing representations using

visualizations of hierarchical trees.

Participants in the user test were asked to

verbalize their intentions while performing the

mapping tasks, while being observed by a

researcher. Prompts were only provided if the user

was unable to proceed. This was in combination

with screen recording for subsequent analysis of the

actions taken and the notes of the researcher. Users

are asked to formulate any question or comments for

discussion with the researcher after the event.

Each task was presented as a task of assigning

codes SNOMED CT as the name itself of the above

archetypes as well as the data fields they contain. In

this case, the breakdown in subtasks was user

initiated, as they were given freedom to decide from

where to start and what archetype elements to map.

The users were exposed directly to the user interface

of the browser, and let alone to guess what features

they should use (the search for concepts, for

example). The openEHR CKM was not showed or

explained, and the concept of archetype was

simplified and users were not exposed to the

complexities of the ADL formal language.

Concretely, the archetypes were explained using

plain text without any reference to concrete

standards, languages or mappings. This avoided

confusions or difficulties that are external to the

central task of finding SNOMED concepts that map

MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY BROWSERS - How Usable are them for Describing Clinical Archetypes?

415

to archetypes or their components.

Finally it was decided not to ask for post-

coordinated expressions as a possible solution in the

SNOMED CT code assignment, as this would

require prior training and requires some knowledge

of the SNOMED formal language. Instead, it was

asked to users to informally express the

identification of an archetype or part of it as a

combination of SNOMED CT terms rather than a

single term.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A room with several computers with the two

browsers installed (CliniClue and Minnow) was

used for the text. In addition, each team had an

Internet connection to allow the user to each of the

two online surveys, the part of usability by entering

the personal and professional data and the SUMI

questionnaire of 50 questions for further automatic

processing. Each participant was accompanied by an

observer to collect interesting data using the "Think

Aloud" protocol.

4.1 Participants

Users who participated in this study were all active

professionals coming from different health

institutions including the University Hospital of

Fuenlabrada, Clinic Hospital San Carlos, 12 de

Octubre Hospital and Henares Hospital in Coslada,

all of them in the Madrid region.

The study involved a total of 14 participants (8

women and 6 men). As the cost-benefit ratio is

considered lower applying the tests 3 to 5 users

(Nielsen, 1993), no additional users were considered

for this initial exploratory study.

The ages of the participants ranged from 34 to 52

years the average age being 40 years, all of Spanish

nationality.

As for the experience of participants in the health

context, the average was 15 years and his previous

experience with medical terminologies did not reach

33%.

As for the time spent in completing this test, it

varied according to the previous experience of

participants with clinical terminologies as well as

browsers of this type. In mid-range, it was situated at

72 minutes in the realization of global test.

Interestingly, in this case it was that less time spent

in conducting the test with the browser Minnow than

the browser CliniClue.

In all cases, participants expressed the

importance of the linguistic barriers (the browsers

are in English) that they found on search the

concepts in other language than their own. While

some had experience with clinical terminologies,

they had always worked with the Spanish version of

SNOMED CT.

4.2 Usability of the Browsers

Regarding the usability of the browser, after

collecting data from users in the SUMI questionnaire

on each browser, results were compiled and

descriptive statistics applied.

In the case of CliniClue, the highest levels were

obtained in the Efficiency subscale, while the lowest

corresponded to the subscales of Helpfulness and

Control, i.e., users perceived a lack of friendliness in

the search interface and of control in the search

process, instead, assessed the performance aspects of

the program as well as the level of satisfaction in

their management (affected).

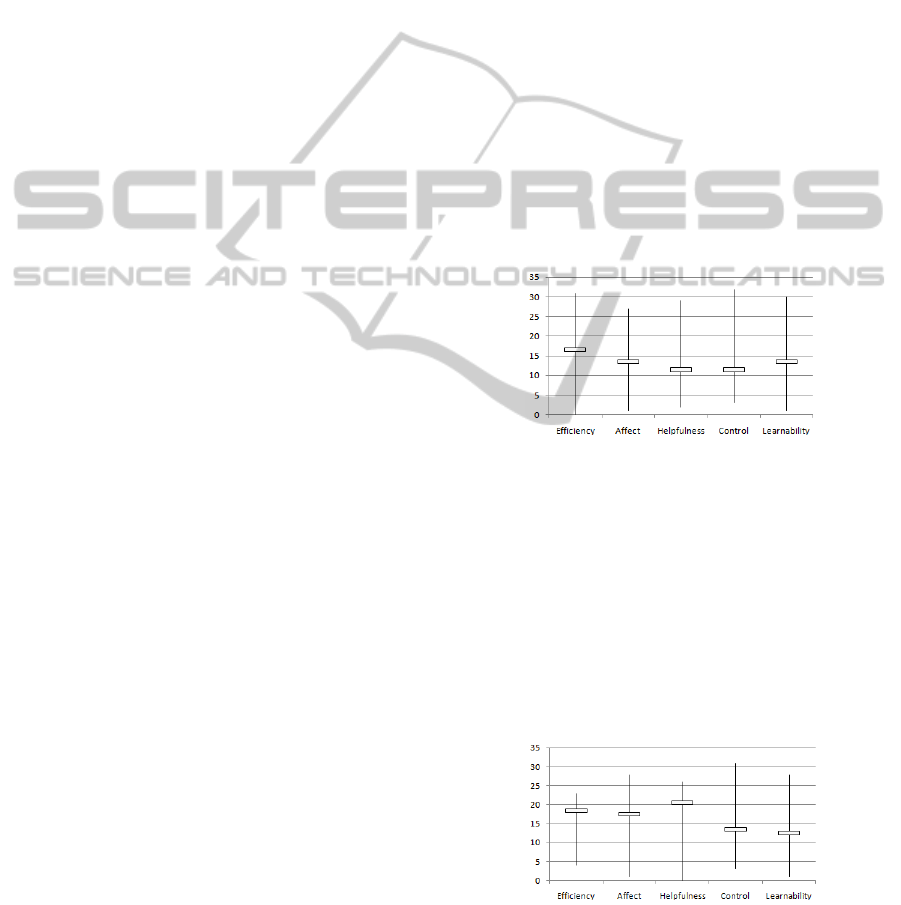

Figure 1: Quantitative measurements of the usability of the

CliniClue browser.

In the case of Minnow, the levels are clearly

higher than CliniClue. The highest levels

corresponded to the subscales of friendliness and

satisfaction in their use. Participants generally

viewed the multimedia component of this browser

and the arrangement of windows in the interface

very useful and explanatory. Lower levels in this

case corresponded to the lack of control and

learnability.

Figure 2: Quantitative measurements of the usability of the

Minnow browser.

The following graph shows an overview of the

HEALTHINF 2012 - International Conference on Health Informatics

416

results. It is clear that participants in this study

clearly preferred Minnow.

Figure 3: Comparative results of measurements obtained

in the usability study.

As for the protocol "Think aloud" some

conclusions could be considered quite significant. It

is important to note first that The indicators explored

were:

Complexity of the test.

Comments on the proposed archetype and all the

data it contains.

Observations on the coding of these data.

Regarding the test itself, the perception of most

participants (84%) was that it had not much

complexity, also they agree in stating that they had

found the test very complete. Regarding the duration

of the same they all considered too long, answering

the question asked at the end of the test by the

observer.

In regard to the proposed archetypes, most of the

comments received were related to the inability to

find some of the proposed concepts. In some cases

this lack of results in the searches occurred in both

browsers, at other times produced results in only one

of them. The following chart shows the total number

of concepts located in both a browser and in another

by all members of the study.

Was also seen that the encoding proposed by the

users varied markedly. The level of agreement did

not reach 10% for participants in the study. Possible

causes are the difference in the search engines of the

two software or differences in the visualization of

concepts as which they could infer dramatically in

the final choice of concept. A source of differences

found was concepts that are related lexically but

refer to different kinds of entities as defined in

SNOMED CT high level categories.

Although in all cases there was this mismatch of

proposed coding, all participants agreed in their

positive attitude towards the test performed and their

willingness to use of terminology standards as a

necessary step to achieve semantic interoperability

of medical systems.

5 CONCLUSIONS

A usability evaluation of the browsers tested is

plausible and appears as a relevant technique to

gather more information in devising SNOMED CT

browsers. This study provides a better understanding

of the usefulness of SNOMED CT terminology

standard and their use in identifying the concepts of

archetypes. In this sense it has been shown that

using SNOMED CT codes for the identification of

the concepts that make up a openEHR archetype is

feasible, but entails some difficulties from the side

of the user that deserve further attention if reliable

and consistent coding is sought.

This study has also proven the effectiveness of

the protocol "think aloud" in the participant's

registration information with the figure of an

observer.

Future work will extend the exploratory usability

studies to a wider range of SNOMED CT browsers,

and to search and browsing tasks following a finer

grained approach in task descriptions.

Anyway this study is certainly relevant to

government agencies and institutions as well as

companies that are committed to interoperability of

medical systems using teminologies standards such

as SNOMED CT with clinical standards UNE/EN

ISO13606.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by the project

“Métodos y Técnicas para la Integración Semántica

de Información Clínica mediante Arquetipos y

Terminologías (METISAT)”, code CCG10-

UAH/TIC-5922, funded by the Community of

Madrid and the University of Alcalá.

Likewise, this research work has been partially

supported by projects PI09-90110 - PITES -

from "Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) Plan

Nacional de I+D+i", "Plataforma en Red para el

Desarrollo de la Telemedicina en España" and FIS

08-1148 "Representación de información clínica en

cáncer de mama mediante arquetipos".

REFERENCES

Arh T. Blazic B. J., (2008). A Case Study of Usability

Testing - The SUMI Evaluation Approach of the

EducaNext Portal. In Wseas Transactions On

Information Science & Applications. Issue 2, Volume

5, p. 175 – 181. ISSN: 1790-0832.

MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY BROWSERS - How Usable are them for Describing Clinical Archetypes?

417

Balbo, S., Steinkrug, J., Lee, L., Scheidt, S., Hullin, C. and

Gogler, Janetter, (2008). The Importance of Including

Users in Clinical Software Evaluation: What Usability

Can Offer in Home Monitoring. In: Grain, Heather

(Editor). HIC 2008 Conference: Australia's Health

Informatics Conference, August 31 - September 2,

2008 Melbourne Convention Centre

Beale T., (2002). Archetypes: Constraint-based Domain

Models for Future-proof Information Systems

Beale, T. and Heard, S., (2007). Anontology-based model

of clinical information. MEDINFO 2007: Proceedings

of the 12th World Congress on Health (Medical)

Informatics: Building Sustainable Health Systems:

760-764.

Borovicka M., Laschitz L. et al., (2010). Chaos or

Content: Towards Generic Structuring of Medical

Documents by Utilisation of Archetype-Classes, In:

Schreier G, Hayn D, Ammenwerth E. (Eds.):

eHealth2010 - Health Informatics meets eHealth:

Tagungsband eHealth2010 & eHealth Benchmarking

2010, in OCG Books Band 264. Wien: OCG. S. 47-54.

Duo Wei, B. S., Yue Wang, Yehoshua Perl, Junchuan Xu,

Michael Halper, and Kent A. Spackman. Complexity

Measures to Track the Evolution of a SNOMED

Hierarchy. Proceedings of the American Medical

Informatics Association Symposium, 2008: 778-782

Elhanan, G., Perl, Y. and Geller, J., (2010) A Survey of

Direct Users and Uses of SNOMED CT: 2010 Status

AMIA AnnuSympProc. 2010; 2010: 207–211.

Ericsson, K. and Simon, H. A., (1980). Verbal reports as

data. Psychological Review, 87, 215-251

Ericsson, K and Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol Analysis.

Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Gilb T. (1987) Principals of Software Engineering

Management, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass.

Harper, B. D. and Norman, K. L., (1993). Improving User

Satisfaction: The Questionnaire for User Interaction

Satisfaction Version 5.5. Proceedings of the 1st

Annual Mid-Atlantic Human Factors Conference, (pp.

224-228), Virginia Beach, VA.

Jaspers, M. W., (2009). Comparison of usability methods

for testing interactive health technologies:

Methodological aspects and empirical evidence,

International Journal of Medical Informatics, 78(5),

pp. 340-353

Kirakowski, J., Corbett, M., (1993). SUMI: The Software

Usability Measurement Inventory. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 24(3), pp. 210-212.

Lewis, C., (1982). Using the thinking-aloud method in

cognitive interface design. IBM Research Report RC

9265, Yorktown Heights, NY, 1982.

Lewis, J. R., (1995): IBM Computer Usability Satisfaction

Questionnaires: Psychometric Evaluation and

Instructions for Use. International Journal of Human

Computer Interaction. 7, 57-78.

Muñoz, A., Somolinos, R., Pascual, M., Fragua, J.,

González, M., Monteagudo J. L., Hernández, C.,

(2007). Proof-of -concept Design and Development of

an EN13606-based Electronic Health Care Record

Service. Journal American Medical Information

Association (2007;14:118 –129. DOI 10.1197/jamia.

M2058.)

Nielsen J., (1993). Usability Engineering. AP

Professional. Boston (MA), USA,

Nielsen, J and Levy, J (1994). Measuring usability:

preference vs. performance. Communications of the

ACM, Vol. 37, No. 4. (April 1994), pp. 66-

75. doi:10.1145/175276.175282 Key: citeulike:

296786

Nilsson, O. y Olsen, J., (1995). Measuring Consumer

Retail Store LEALTADalty. European Advances in

Consumer Research, 2, pp. 289-297.

Rogers, J. and Bodenreider, O., (2008) SNOMED CT:

Browsing the Browsers. Proceedings of the 3rd

international conference on Knowledge

Shackel, B., (1991). Usability – context, framework,

design and evaluation. In Shackel, B. and Richardson,

S. (eds.). Human Factors for Informatics Usability.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 21-38.

Tullis, T. S. and Stetson, J. N., (2004, June 7-11). A

Comparison of Questionnaires for Assessing Website

Usability, Usability Professionals Association (UPA)

2004 Conference, Minneapolis, USA.

Van Veenendaal, E., (1998). Questionnaire based usability

testing. In Proceeding of European Software Quality

Week, Brussels.

Wollersheim D., Sari A., Rahayu W., (2009). Archetype-

based electronic health records: a literature review and

evaluation of their applicability to health data

interoperability and access. HIM J 38: 7–17.

HEALTHINF 2012 - International Conference on Health Informatics

418