EVALUATION OF ENTERPRISE TRAINING PROGRAMS USING

BUSINESS PROCESS MANAGEMENT

Fod´e Tour´e and Esma A¨ımeur

D´epartement d’Informatique et de Recherche Op´erationnelle, Universit´e de Montr´eal, Montr´eal, Canada

Keywords:

Business Process Management, Business Intelligence, e-Learning, Evaluation, Return on Investment,

Optimization, Business Activity Monitoring, Machine Learning Algorithms.

Abstract:

The investment in human capital, by means of training delivered in enterprise, became an important constituent

of enterprise competitiveness strategy. Consequently business managers require from their human resources

managers, training departments, or even of consultants working in the field of training, the proofs of training

investment yield in terms of tangible and intangible profits.

To evaluate training in enterprise, two models predominate, namely the model of Kirkpatrick and that of

Phillips. In this paper, we propose an approach of training project evaluation, based on business process

management. It is an approach which fills the gaps raised in the literature and ensures an alignment between

training activities and business needs.

1 INTRODUCTION AND

PROBLEMATIC

Individual and collective skills are the most important

assets for organizations, and determine their produc-

tivity, competitiveness and ability to adapt and to be

proactive when uncertain. Training is a key strategy

for generating skills in people. This is why investment

in training is high; the American Society for Training

& Development (ASTD) estimated this investment to

126 billion USD in 2007 (Paradise, 2007).

Many organizations assess whether learners liked

a course or acquired new knowledge, but few have

cracked the code on how to determine learning Re-

turn On Investment (ROI). The most commonly used

metrics for evaluating training programs are those de-

rived from the work of Donald L. Kirkpatrick (Kirk-

patrick, 1994) and Phillips (Phillips, 1996). Table 1

shows the measures of course evaluation reported in

the 2008 Benchmarking Study conducted by Corpo-

rate University Xchange.

There are several models in the literature. Some

of these models allow calculating the return on the in-

vested capital, and could help organizations to make

better educated decisions regarding workforce train-

ing. However, because of the difficulties bound to

the use of these models, human resource departments

cannot estimate, in a concrete way, the impact of the

training on the economic and social growth of their

Table 1: Course Evaluation Methods by Level, in (Rozwell,

2009).

Course Evaluation Method Percentage of Courses

Evaluated Using

this Method

Level 1: opinion of the course

and instructor

75%

Level 2: knowledge acquisition 47%

Level 3: behavior change 20%

Level 4: business impact 12%

Level 5: return on investment 6%

enterprise.

A study, led by ASTD and Institute for Corpo-

rate Productivity’s (i4cp), shows that few organiza-

tions feel they have mastered the learning evaluation,

and many admit to face ongoing challenges (Patel,

2010). Besides, methodological problems are also

highlighted by respondents, in particular for evalu-

ation levels 3, 4 and 5 (the level 5 corresponds to

Phillips’ model) and isolation of training effects in the

results.

In this paper, we propose a training project man-

agement approach based on business process manage-

ment: going from concept to optimization, via the

evaluation of the financial and non financial yield.

In the remainder of this paper, we shall present,

in section 2, the two basic models for evaluating the

training in enterprise, the advantages and criticism of

505

Touré F. and Aïmeur E..

EVALUATION OF ENTERPRISE TRAINING PROGRAMS USING BUSINESS PROCESS MANAGEMENT.

DOI: 10.5220/0003837305050510

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2012), pages 505-510

ISBN: 978-989-8565-08-2

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

these models. Section 3 will be dedicated to the pre-

sentation of our model and a final conclusion is pre-

sented in section. 4.

2 THE KIRKPATRICK/PHILLIPS

MODEL

The concept of yield covers a rather wide spectrum,

going from effect perception to the return on invest-

ment calculation. These two dimensions join the

distinction between ”financial yield” to describe the

measure or the calculation of what the training brings

to the organization on financial plan and ”training re-

sults” to describe the impact or the effects which are

not of financial nature.

Kirkpatrick’s model began in 1959, with a series

of four articles on the evaluation of training programs

in the journal ”Training and Development”. These

four articles defined the four levels of evaluation that

would later have a significant influence on corporate

practices.

The four levels of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model

essentially measure (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick,

2006; Kirkpatrick, 1994):

Level 1 - Students Reaction

How did the trainees react after the training? Did they

appreciate this one? Are they satisfied? What they

thought and felt about the training.

Level 2 - Learning

What they learnt after the training? What knowledge,

skills and/or attitudes (knowledge, know-how, and social

skills) have been acquired? Have educational objectives

been achieved? The resulting increase in knowledge or

capability. It is about the educational evaluation.

Level 3 - Behavior

Do the trainees use what they learned in training at their

workstations? What new professional behaviors have

been adopted? Extent of behavior and capability im-

provement and implementation/application.

Level 4 - Results

What is the impact of the training on the results of the

company? Example: decrease of the rate of absenteeism,

occupational accidents, growth of turnover, the produc-

tivity, customer satisfaction, etc. The effects on the busi-

ness or environment resulting from the trainee’s perfor-

mance.

Although the four-level model of Kirkpatrick is

widely recognized and accepted, and although a sig-

nificant number of evaluation methods find their base

there, many have argued that this method does not

provide the data required by managers today, which

Phillips has to overcome.

According to Phillips, the calculation of the yield

of the training is made by means of a process by

stages which supplies a plan detailed for the plan-

ning, the collection and the data analysis, which in-

cludes the calculation of ROI (Phillips, 1996; Phillips

and Stone, 2002; Phillips and Phillips, 2003). The

process begins with the evaluation planning: where

objectives are developed and decisions are taken on

the way the data will be collected, treated, and ana-

lyzed. The data collection is made according to train-

ing evaluation levels (level 1: reactions/satisfaction;

level 2: learning; level 3: transfer of the learning and

the level 4: the organizational results). Finally, at the

level of the data analysis, we have the crucial stages

for the analysis of ROI:

• Isolate the effects of the training from other fac-

tors of influence (use of one or several methods

to separate the influence of the training project of

the other factors which influence the measure of

the organizational results),

• Convert the data concerning the organizational

impacts into money values for developing an an-

nual value of the project,

• Profits and costs are combined in the ROI calcu-

lation,

• The intangible profits are identified by this pro-

cess (they are included in this category only after

having tried to convert them in money values).

In conclusion, training is a key strategy for staff

development and for achieving organizational objec-

tives. Organisations and public authorities invest

large amounts of resources in training, but rarely have

the data to show the results of that investment. Only a

few organisations evaluate training in depth due to the

difficulty involved and the lack of valid instruments

and viable models (Pineda, 2010). The entire notion

of the Kirkpatrick/Phillips model may not truly mea-

sure the impact of the Learning Function on the orga-

nization, even under the most optimistic scenarios. It

measures only the possible impact of isolated training

events (Mumma and Thatcher, 2009).

Thus, to try to bring a solution to the enterprise

needs, we present in the following section an ap-

proach of training yield evaluation, based on the busi-

ness process management.

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

506

3 A MODEL OF TRAINING

EVALUATION BASED ON

BUSINESS PROCESS

MANAGEMENT

Business Process Management (BPM) represents a

strategy of managing and improving business perfor-

mance by continuously optimizing business processes

in a closed-loop cycle of modeling, execution, and

measurement. A global study by Gartner confirmed

the significance of BPM with the top issue for CIOs

identified for the sixth year in a row being the im-

provement of business processes (Gartner, 2010).

Given the success registered by the BPM solutions

in the management of enterprise processes, why not

use this approach to manage, efficiently, the training

activities in enterprise? An affirmative answer to this

question supposes that we have to consider these ac-

tivities as being business processes.

Indeed, to design and realize a training project

supposes getting through various stages: going from

the formulation of a request up to the implementation

of new skills. The reality in most enterprises is that

they need to figure out how to make their spending

for training have a greater impact on corporate perfor-

mance. When training needs are viewed with a criti-

cal eye, many organizations will find that they simply

do not have enough money to train every employee

equitably. So they need to focus their training expen-

diture on the roles that are most essential for business

success and that return the most value to the organiza-

tion. That’s why, for the management of the training

projects in enterprise, we propose an approach based

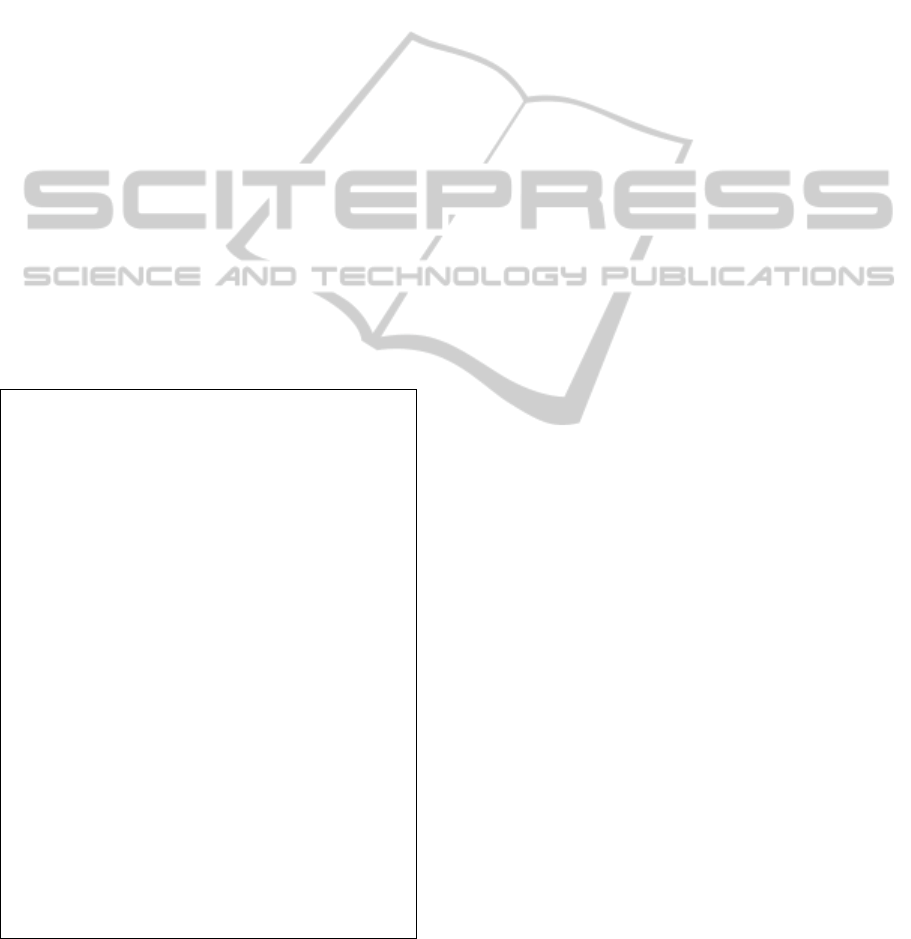

on five stages, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Steps of management of a training program in

enterprise.

In the following subsections we present the stages

of our approach. To facilitate the understanding, we

use the following sample scenario:

In an enterprise of software development, the fi-

nancial manager notes an increasing of penalties

owed to the delivery delay. After analyzing the situa-

tion , he remarks that the delays are bound to projects

which integrate the programming in Xforms. Hence,

the enterprise decides to offer an accelerated train-

ing to its employees. The training cost is estimated

at 72000$. The training is offered in the afternoons

(therefore, employees work half-time). How to insure

a simple and effective management of this project?

3.1 Stage 1: Study of Training Project

The first stage of our approach consists of analyzing

the demand for training and associating it with ele-

ments of performance of the enterprise. It is translated

by a certain number of actions such as: the conversa-

tions of exploration of the demand, the definition of a

plan of change, needs analysis, definitions of the ob-

jectives, the definition and the choice of performance

indicators.

In the scenario above, it is important to isolate,

first of all, indicators associated to the problem: cost

of delay in delivery, number of software deliveredlate,

cumulative time of delay....

Necessary to take into account factors which can

have the same effect. These correspond to the fol-

lowing indicators:staff turnover rate, employee’s ab-

senteeism rate,number of absence per employee, rea-

son of absence, cost of rotation, cost engendered by

the absenteeism, cost of absence per employee, job

satisfaction degree, personal initiative degree, staff

productivity, collaboration level between employees

within the enterprise, collaboration level per em-

ployee....

Having identified factors bound directly or indi-

rectly to the problem, it is necessary to calculate the

real cost of training for the ROI calculation. For our

scenario, we must add the losses incurred by the en-

terprise during the training period, the cost of time de-

voted to the identification, and needs analysis (com-

bined time of employee, supervisor. ..). Finally, it

is necessary to define the objectives of the training

and to link them to enterprise business needs. In our

scenario, it is to decrease the ”cumulative delay time

”that is linked to the turnover of the enterprise by the

cost of delay penalties. In other words, it is a question

of insuring an alignment between the objectivesof the

training and the business needs.

3.2 Stage 2: Modeling and Validation

To model a business process, we use graphic objects

EVALUATIONOFENTERPRISETRAININGPROGRAMSUSINGBUSINESSPROCESSMANAGEMENT

507

developed by Workflow Management Coalition

(WFMC, 1999).

A business process model can contain two types of

structural conflict: deadlock and lack of synchroniza-

tion (Sadiq and Orlowska, 1999; van der Aalst et al.,

2002; Lin et al., 2002; Sadiq et al., 2004). In order to

verify or to assure the correctness of a process model,

we use an algorithm based on reduction-based al-

gorithms and graph-traversal algorithm (Tour´e et al.,

2008).

For the management of a training project, there are

at least two process models: the process model bound

to the training planning and the process model bound

to the stages of evaluation of the training yield (in-

cluding the stages of evaluation presented in the sec-

tion 2). In this stage, we define indicators allowing

evaluating the training. These indicators allow react-

ing in real time to push aside any situation which can

lead to the failure of the training (non-achievement of

objectives).

The training planning is a graphic representation

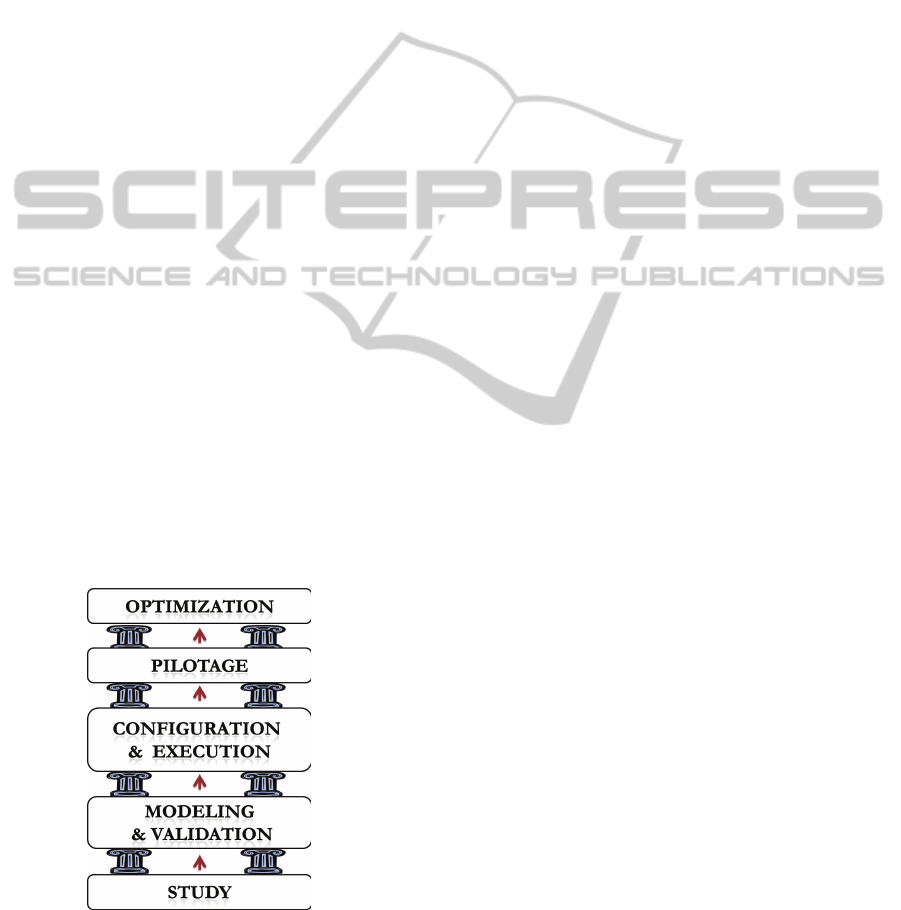

of training progress stages. Figure 2 shows a possi-

ble process model, corresponding to our example (the

software development enterprise).

Figure 2: A possible process model for training planning.

We associate to this graph (Figure 2), the actors

of each stage, the temporal aspect and the perfor-

mance indicators linked to the training conduct. As

indicators, we can quote: average emotional state per

learner, average emotional state per training session,

general emotional state per training, satisfaction as

for the training program organization, satisfaction as

for the contents, satisfaction towards the trainer, rele-

vance of the perception, the utility and capacity of the

training to reach its objectives, note by examination,

average score of learning,.. ..

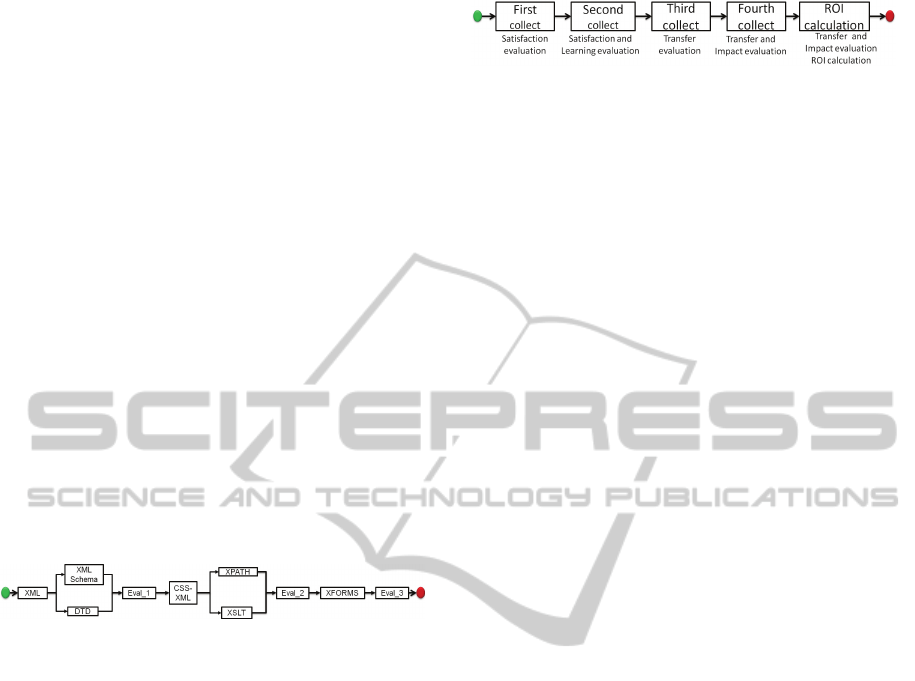

The training evaluation planning is a representa-

tion of information collecting stages, during and after

the training (Figure 3). With this graph, we must de-

fine the collecting means, the date, the objectives, the

actors and corresponding indicators. We also define

indicators allowing estimating the achievement of the

objectives of the training in enterprise. These indi-

cators are related to employee’s life in the company

after the training. We can add for example: increase

of innovation degree of an employee, increase of in-

novation degree in the enterprise, improvement of the

quality of the product, climate at work, number of

committee meetings, customer loyalty, earnings per

employee, ROI. .. .

Figure 3: A possible process model for training evaluation

planning.

After the modeling, we must validate the process

models by taking into account the structure, actions,

data flows and the temporal aspect.

3.3 Stage 3: Configuration and

Execution

A Business Process Management System (BPMS) is

an integrated collection of software technologies that

enables the control and management of business pro-

cesses. Compared with other model oriented develop-

ment tools, such as integrated service environments

and integrated development environments, a BPMS

emphasizes business user involvement in the entire

process improvement life cycle. As a discipline, BPM

is about coordination, rather than control (via au-

tomation) over resources. Beyond task automation, a

BPMS coordinates human interactions and informa-

tion flows in support of work tasks. People, infor-

mation, systems and, increasingly, business policies

are treated as equally important resources that affect

the desired work outcome. This comprehensive ap-

proach to resources also distinguishes a BPMS from

other emerging model-driven application infrastruc-

ture (Gartner, 2009).

This stage is dedicated to the evaluation before

and during the execution, the initialization of indica-

tors by their current values in the enterprise before the

execution of the project of training. The choice of in-

dicators depends on the type of training and especially

the target objectives of the enterprise.

The execution corresponds to the operational

phase where the solution of BPM is implemented. It

is in this stage that the evaluation of levels 1, 2 and

sometimes level 3 of the model of Kirkpatrick (dur-

ing execution some of indicators will already be under

observation) is performed.

3.4 Stage 4: Monitoring

This stage consists in controlling the progress of the

processes. A control based on precise indicators and

relevant in order to have dashboards allowing mak-

ing quickly the good decisions. The dashboard of

the training has to cover two big dimensions: the ef-

ficiency and the efficacy. The training process said

to be efficient if it gives the maximum of results by

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

508

consuming the minimum of resources and said to be

effective if it gives the expected results.

The dashboard of the efficiency of the training

will be composed of indicators of consumption of re-

sources and of activities output allowing measuring

the efficiency of each of the three stages of the pro-

cess, as well as the general efficiency of the train-

ing project. The following indicators allow building

the dashboard of the efficiency of a training program:

time dedicated to the identification and to the needs

analysis (combined time of the employee, his supe-

rior and the training manager), perceived usefulness

of the training/time dedicated, the gap enters what the

employee masters and what he has to master, the ad-

equate level of training to reduce or cancel the gap

(beginner, intermediate, advanced), mode of training

(external, intern, coaching, e-learning, tutoring, etc.),

time to design and the elaboration of the program, etc.

These indicators can be analyzed by sex, seniority, so-

cial status, type of training, or operational unity (ser-

vice, department, store, etc.). The dashboard of the

effectiveness focuses either on the effectiveness of a

training, or on the global effectiveness of the training

system. Its structure includes the model of training

evaluation and contains more indicators than the effi-

ciency dashboard.

This stage allows us to calculate the tangible and

intangible training benefits (without additional costs)

by using indicators values.

3.5 Stage 5: Optimization

In this stage of our approach, we use machine learning

algorithms (example, logistic regression, neural net-

works or support vector machines) to classify train-

ing activities according to defined criteria (example,

financial yield) and to do simulations to increase the

efficiency and efficacy of training activities. For this,

we realize a pretreatment on the indicator values to

have a data set for a supervised learning algorithm,

unsupervised or semi-supervised.

When the training evaluation process is com-

pleted, the enterprise training programs will be clas-

sified in two categories: profitable and unprofitable.

Hence, we will have a dataset D

n

that can be used in

training of a machine learning algorithm.

D

n

= {Z

1

, Z

2

, . . . , Z

n

}

∀i ∈ {1, 2, . . . , n}, Z

i

= (x

(i)

, y

(i)

) with x

(i)

∈ R

d

and

y

(i)

) ∈ {0, 1}

Each Z

i

is associated to a particular training program

in the enterprise. The x

(i)

are the indicators (see 3.1

and 3.2) related to the training, y

(i)

represents the

training class (profitable or unprofitable), n is the

number of completed training program and d is the

number of indicators.

It is obvious that to use this data set with a machine

learning algorithm, it is necessary to make a pretreat-

ment to standardize or normalize the inputs x

(i)

.

The purpose of the classification is to be able to

predict the achievement or none achievement of the

training objectives by observing only the indicators

behavior. Furthermore, we must be able to determine

the indicators which have more weight in the realiza-

tion of training objectives. That’s why we may use

a parametric machine learning algorithm like logistic

regression, neural networks or the support vector ma-

chines.

The optimization consists of a simulation allow-

ing guiding the training process towards objectives

achievement. To do this we may use semi-supervised

learning. Semi-supervised learning is of great inter-

est in machine learning and data mining because it

can use readily available unlabeled data to improve

supervised learning tasks when the labeled data are

scarce or expensive. Semi-supervised learning also

shows potential as a quantitative tool to understand

human category learning, where most of the input is

self-evidently unlabeled (Zhu and Goldberg, 2009).

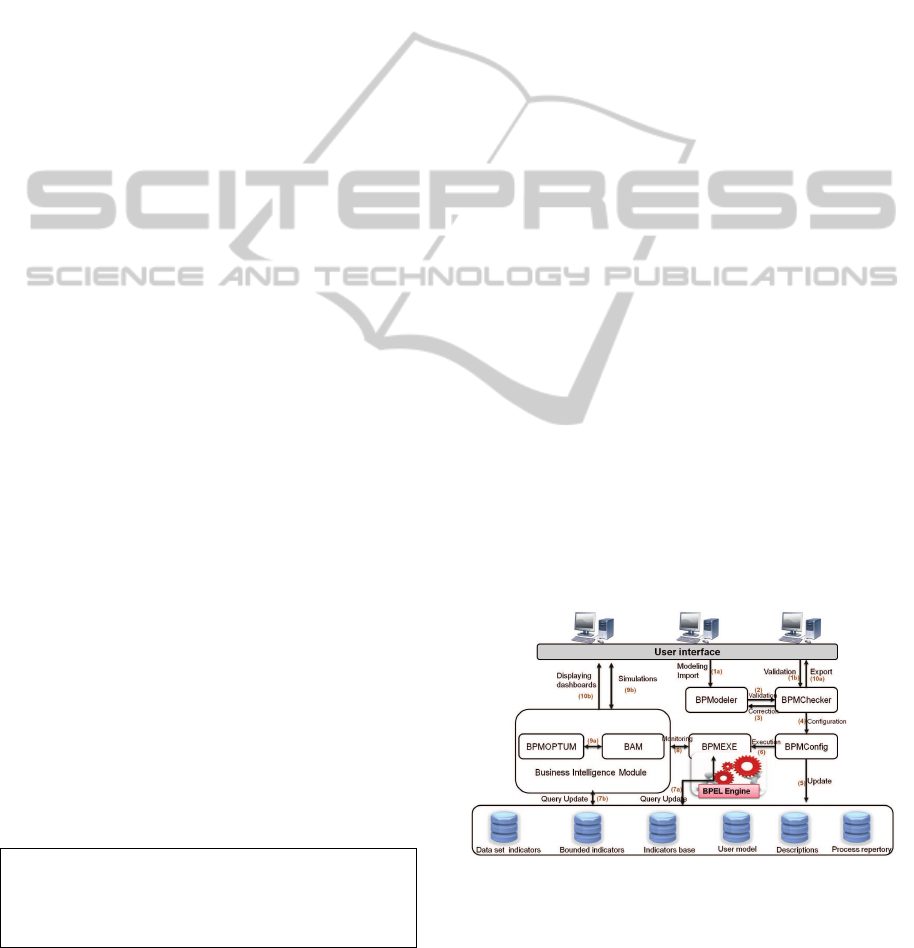

To materialize our approach, our objective is to

provide a tool (Figure 4) to help the training projects

management in enterprise with the alignment between

the training activities and business needs, modeling

and validating of the training processes, execution and

supervision of training projects, calculation of tangi-

ble and intangible profits of training, classification of

trainings (in two levels: enterprise - employee), train-

ings optimization (in two levels: employee - enter-

prise).

Figure 4: Architecture of our enterprise training processes

management system.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Business Process Management (BPM) was once de-

EVALUATIONOFENTERPRISETRAININGPROGRAMSUSINGBUSINESSPROCESSMANAGEMENT

509

fined in terms of tools and technologies, it has re-

cently emerged as a discipline encompassing a broad

spectrum of organizational practices. As a result,

the skillsets for BPM endeavors of today’s organiza-

tions have gone beyond the automation of processes

to encompass a wide variety of strategic and techni-

cal skills (Antonucci, 2010). The advantages obtained

through our approach can be seen from two angles. In

the domain of business process management, we add

a new category of business process and extend BPMS

by adding the validation pre-execution (through our

tool).

Concerning the evaluation of enterprise training,

we propose a complete approach of training project

management facilitating decision-making and the cal-

culation of the tangible and intangible profits. With

regard to the existing models, we add a level of di-

agnostic (classification and optimization) allowing to

understand the dysfunctions related to the attainment

or not attainment of training objectives. Our approach

ensures the training activities alignment with business

needs and allows the ROI calculation without addi-

tional investment.

Concerning the problems raised in the literature,

we reduce the bias and additional costs bound to train-

ing yield calculation. Indeed, from the beginning, we

associate the effects expected by the training with cer-

tain indicators that it already uses in the current man-

agement of the enterprise. When financial yield eval-

uation is required, it will be thus able, without addi-

tional costs, to provide data on the quantitative indi-

cators which will show the evolution of productivity

and quality and will be able to translate them into eco-

nomic value.

REFERENCES

Antonucci, Y. L. (2010). Business process management

curriculum. In Bernus, P., Blazewics, J., Schmidt,

G., Shaw, M., Brocke, J., and Rosemann, M., editors,

Handbook on Business Process Management 2, Inter-

national Handbooks on Information Systems, pages

423–442. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-

3-642-01982-1 20.

Gartner (2009). Magic quadrant for business process man-

agement suites. Gartner Research.

Gartner (2010). Leading in times of transition. The 2010

CIO Agenda. Stamford, CA, USA.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1994). Evaluating training programs

: the four levels / Donald L. Kirkpatrick. Berrett-

Koehler ; Publishers Group West [distributor], San

Francisco : Emeryville, CA :, 1st ed. edition.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. and Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evalu-

ating Training Programs: The Four Levels (3rd Edi-

tion). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 3rd edition.

Lin, H., Zhao, Z., Li, H., and Chen, Z. (2002). A novel

graph reduction algorithm to identify structural con-

flicts. In HICSS, page 289.

Mumma, S. and Thatcher, C. (2009). The learning profit

chain ”connecting learning investments to financial

performance”. Corporate University Xchange.

Paradise, A. (2007). State of the industry: Astd’s annual re-

view of trends in workplace learning and performance.

Alexandria, VA: ASTD.

Patel, L. (2010). Overcoming barriers and valuing eval-

uation. Learning Circuits - ASTD’s Source for E-

Learning. American Society for Training & Devel-

opment.

Phillips, J. and Stone, R. (2002). How to Measure Training

Results: A Practical Guide to Tracking the Six Key

Indicators. McGraw-Hill, hardcover edition.

Phillips, J. J. (1996). Roi: The search for best practices.

Training & Development, 50(2):42–47.

Phillips, J. J. and Phillips, P. P. (2003). Using action plans

to measure roi. Performance Improvement, 4:24–33.

Pineda, P. (2010). Evaluation of training in organisations: a

proposal for an integrated model. Journal of European

Industrial Training, 34 Iss: 7:673–693.

Rozwell, C. (2009). Forget roi, measure time to compe-

tency to calculate learning value. Gartner Research,

(G00169917).

Sadiq, S., Orlowska, M., Sadiq, W., and Foulger, C.

(2004). Data flow and validation in workflow mod-

elling. In ADC ’04: Proceedings of the 15th Aus-

tralasian database conference, pages 207–214, Dar-

linghurst, Australia, Australia. Australian Computer

Society, Inc.

Sadiq, W. and Orlowska, M. E. (1999). Applying graph re-

duction techniques for identifying structural conflicts

in process models. In CAiSE, pages 195–209.

Tour´e, F., Ba¨ına, K., and Benali, K. (2008). An efficient

algorithm for workflow graph structural verification.

In Meersman, R. and Tari, Z., editors, OTM Confer-

ences (1), volume 5331 of Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, pages 392–408. Springer.

van der Aalst, W. M. P., Hirnschall, A., and Verbeek, H. M.

W. E. (2002). An alternative way to analyze workflow

graphs. In CAiSE, pages 535–552.

WFMC (1999). Workflow management coalition interface

1: Process definition interchange process model.

Zhu, X. and Goldberg, A. B. (2009). Introduction to Semi-

Supervised Learning. Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

510