WEB INFORMATION GATHERING TASKS AND THE USER

SEARCH BEHAVIOUR

Anwar Alhenshiri, Michael Shepherd, Carolyn Watters and Jack Duffy

Faculty of Computer Science, Dalhousie University, 6050 University Ave., Halifax, NS, Canada

Keywords: Information Retrieval, Web, Tasks, Information Gathering, Behaviour.

Abstract: The research described in this article is an attempt to characterize the kind of search behaviour users follow

while gathering information on the Web. Information gathering on the Web is a task in which users collect

information; possibly from different sources (pages); more likely over multiple sessions to satisfy certain

requirements and goals. This process involves decision making and organization of the information gathered

for the task. Information gathering tasks have been shown to be search-reliant. Therefore, identifying the

kind of search behaviour users choose for this kind of task may lead to supporting Web information

gathering tools as recommended in the findings of this research. The results of the user study reported in this

paper indicate that the user search behaviour during Web information gathering tasks has characteristics of

both orienteering and teleporting behaviours.

1 INTRODUCTION

To categorize user activities on the Web, researchers

often apply models of information seeking (Ellis,

1993; Marchionini, 1997; Choo et al., 1998).

However, because Web users and Web technologies

evolve rapidly, those models may be obsolete. The

content of the Web—as well as its users—change

over time due to the emergence of new genres,

topics, and communities on the Web (Santini, 2006).

Existing information seeking models have attempted

to categorize user activities. More recent models

have emerged to focus on the narrower behaviour of

users with particular tasks.

There have been different studies in which the

types of activities users perform on the Web were

identified and categorized into higher level tasks.

Examples of models concerning user tasks on the

Web include Broder’s taxonomy (Broder, 2002),

Rose and Levinson’s classification (Rose and

Levinson, 2004), Sellen’s model (Sellen et al.,

2002), and Kellar’s categorization of information

seeking tasks (Kellar et al., 2007). The results of

those studies indicate that each task can be further

studied for understanding the subtasks involved in

the overall task.

Alhenshiri et al. (2010) presented a model in

which the task of Web information gathering was

divided into subtasks each of which involves

activities of similar nature that users perform on the

Web during the task. The process of information

gathering on the Web has been shown to heavily rely

on search and organization of information for the

task (Alhenshiri et al., 2011). The search part of the

process includes activities users perform to locate

pieces of information required in the task which may

involve locating information from different sources,

locating related information to the already located

pieces, and re-finding information in multi-session

tasks (Alhenshiri et al., 2010).

When searching for information on the Web,

users orienteer, teleport, or do both (Teevan et al.,

2004). In the former, users start at a certain page (or

site) and continue searching for information by

following the hierarchy of hyperlinks to find

relevant information. In the latter, users rely heavily

on frequent submissions of search queries to search

engines (or through search features provided on Web

pages) to find relevant information. These two types

of behaviour have been studied by Teevan et al.

(2004) who showed that 61% of user search

activities did not involve keyword search, denoting

orienteering behaviour. Only in 39% of the search

activities, teleporting behaviour was involved.

This paper re-examines the findings of Teevan et

al. (2004) in the case of searching for information

during information gathering tasks on the Web. This

323

Alhenshiri A., Shepherd M., Watters C. and Duffy J..

WEB INFORMATION GATHERING TASKS AND THE USER SEARCH BEHAVIOUR.

DOI: 10.5220/0003910303230331

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2012), pages 323-331

ISBN: 978-989-8565-08-2

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

paper builds on the findings in Alhenshiri et al.

(2010) and investigates the characteristics of user

search behaviour during Web information gathering

tasks. The study described in this paper was also

intended for investigating other aspects of

information gathering on the Web that are reported

in Alhenshiri et al. (2012). The research in this paper

attempts to answer the following questions: (i) Do

users gathering Web information follow a specific

kind of search behaviour (orienteering or

teleporting)? And how can identifying the user

search behaviour benefit the design of future

information gathering tools intended for the Web?

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2

explores the research rationale. Section 3 illustrates

the research study. Section 4 discusses the study

results and findings. The paper is concluded in

Section 5.

2 RESEARCH RATIONALE

Information seeking models have focused on

identifying activities users perform while they

attempt to locate information of interest. The Web

has been treated as a special case in some of the

older models such as Ellis’s (1993). Ellis (1993)

concluded that there are several main activities

applicable to hypertext environments of which the

Web is one. Those activities represent user actions

during seeking information that is not previously

known to the user and which is aimed to increase the

user’s knowledge. Marchionini (1997) stated that the

process of information seeking consists of several

activities (sub-processes) that start with the

recognition and acceptance of the problem and

continues until the problem is either resolved or

abandoned. Wilson and Walsh’s (1996) model of

information behaviour differs from many of the prior

models since it suggests high-level information

seeking search processes: passive attention, passive

search, active search, and on-going search. Although

these models provide accurate characterizations of

users’ information seeking activities, several

activities that users perform on the Web usually are

not included in the model. The variations of those

models and the continuous modifications make it

difficult to choose an appropriate characterization.

Several other frameworks have been suggested to

understand and model the different activities users

perform specifically on the Web while seeking

information. Rose and Levinson (2004) attempted to

identify a framework for user search goals using

ontologies in order to understand how users interact

with the Web. Their findings indicated that users'

goals can be informational, navigational, or

transactional. Similarly, Sellen et al. (2002) found

that user activities can be categorized into finding,

information gathering, browsing, performing a

transaction, communicating, and housekeeping.

Moreover, Broder (2002) studied different user

interactions during Web search and identified three

types of tasks based on the queries submitted by

users. Those types are: navigational, informational,

and transactional. In addition, Kellar et al. (2007)

investigated user activities on the Web to develop a

task framework. The results of their study indicated

that the four types of Web tasks are: fact finding,

information gathering, browsing, and transactions.

Based on the different classifications of Web

tasks, research showed that information gathering

tasks represent a great deal of the overall tasks on

the Web (61.5% according to Rose and Levinson,

2004). Therefore, Alhenshiri et al. (2010) developed

a model in which the subtasks underlying the overall

task of information gathering were identified. Their

research indicated that information gathering is

heavily search-reliant. Prior to this model, Amin

(2009) identified different characteristics in Web

information gathering tasks. Information gathering

was shown to be a more complex task than keyword

search tasks. The terms ‘information gathering’

imply different kinds of search including

comparison, relationship, exploratory, and topic

searches as well as combinations of more than one

type of search (Amin, 2009). Information gathering

tasks are characterized, in part, by having high-level

goals and requiring the use of multiple information

resources (Alhenshiri et al., 2012).

Teevan et al. (2004) identified two types of

search behaviour (viz. teleporting and orienteering)

in e-mails, personal documents, and the Web. In the

former, a searcher is most likely to use keywords

while seeking information. In the latter, a sequence

of steps and strategies is adopted to reach the

intended information, i.e. usually by starting search

at a particular URL and continuing on the Web

hierarchy by following links on Web pages. In this

paper, the two types of behaviour are further

considered in the case of gathering information from

the Web. The goal of this consideration is to decide

on the significance of which type of behaviour for

the information gathering tasks and to eventually

recommend design properties for tools intended for

Web-based information gathering tasks.

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

324

3 RESEARCH STUDY

Information gathering tasks have been shown to be

heavily search-reliant (Amin, 2009; Alhenshiri et al.,

2012) and very popular on the Web as discussed

above. Therefore, the user study discussed in this

section was conducted. The study was meant to

conclude on the kind of behaviour users follow

when performing Web information gathering tasks

which would lead to developing support for the

design of tools intended for this type of task. To

identify the kind of search behaviour users followed

during the task of information gathering, the analysis

in the study considered: (i) the number of URLs

users typed-in to start searching for information; (ii)

the number of keyword queries they submitted; (iii)

the number of links they followed on the Web

hierarchy to locate information for the task; and (iv)

correlations among those factors.

3.1 Study Design and Population

The design of the study was complete factorial and

counter-balanced with random assignment of tasks

to participants. There were 20 participants in the

study, equally split between graduate and

undergraduate students in Computer Science at

Dalhousie University. The study used a special

version of the Mozilla Firefox browser

(http://www.mozilla.com)

called DeerParkLogger,

which was designed at Dalhousie University. This

browser has the ability to log all user interactions

during the task.

3.2 Study Tasks

The study used four information gathering tasks that

were similar in terms of the complexity of the task

and different with regard to the task topic. Each task

was created following the guidelines described by

Kules and Capra (2008) and summarized in the

following:

• The task description should indicate uncertainty,

ambiguity in information need, or need for

discovery.

• The task should suggest knowledge acquisition,

comparison, or discovery.

• It should provide a low level of specificity about

the information required in the task and how to

find such information.

• It should provide enough imaginative contexts for

the study participants to be able to relate and apply

the situation.

To ensure the equality of the tasks with regard to

the complexity level, a focus group met twice to

analyze the tasks and make the necessary

modifications based on: the time needed to complete

the task, the amount of information required to be

gathered, the clarity of the task description, and the

possible difficulties that the user may encounter

during gathering.

3.2.1 Information Gathering Task Example

Part 1. You heard your friends complaining about

bank account service charges in Canada. You are not

sure why they are complaining. You want to do

research on the Web to find out more about bank

account service charges in Canada. State your

opinion about the charges and your friends’

complaints. Keep a copy of the information you

found to support your argument. Provide at most

five links to pages where you found the information.

Keep the information for possible re-use in a

subsequent task.

Part 2. After you found out about the bank service

charges in Canada, you want to compare account

service charges of Canadian banks to those applied

by American banks. Search the Web to find

information about banks in the US. Find at most

information from five pages on the Web. Provide a

comparison of service charges in both countries. Use

the information you kept in the previous task about

the Canadian banks. You should keep a copy of all

relevant information you found for both tasks.

3.3 Study Methodology

Every participant was randomly assigned two tasks

each of which was divided into two parts as shown

in the example above. The reason for splitting each

task was to encourage participants to re-find

information for the second subtask that was

preserved (kept) during the first subtask. The issue

of re-finding is beyond the scope of this paper. Other

aspects including re-finding information are reported

in Alhenshiri et al. (2012). The study had two

questionnaires, a pre-study and two post-task

questionnaires. All user activities were logged

during the study for further analysis.

3.4 Study Results

The user behaviour and its correlation with the kind

of activities users perform during the task of

information gathering were expected to yield certain

findings that would help with the design of future

gathering tools. The results reported in this paper

WEBINFORMATIONGATHERINGTASKSANDTHEUSERSEARCHBEHAVIOUR

325

concern attempts to identify the user search

behaviour during Web information gathering tasks.

Users in the study followed either or both of two

types of search behaviour that were discussed in the

work of Teevan et al. (2004). Those types are

orienteering and teleporting. In the former, a user

starts the search at a specific URL, and continues by

following links on Web pages to find and gather

information. Users of this type of behaviour are

usually expected to follow more links on the Web

and submit fewer search queries to search engines.

In the latter, the user tends to rely on the submission

of search queries more often to locate information.

The user in this case relies less on following

hyperlink connectivity on the Web.

To decide on the type of behaviour users

followed during the tasks, the analysis of the data

considered the number of URLs typed-in, the

number of search queries submitted, the number of

links followed during the task (click behaviour), and

correlations among those factors.

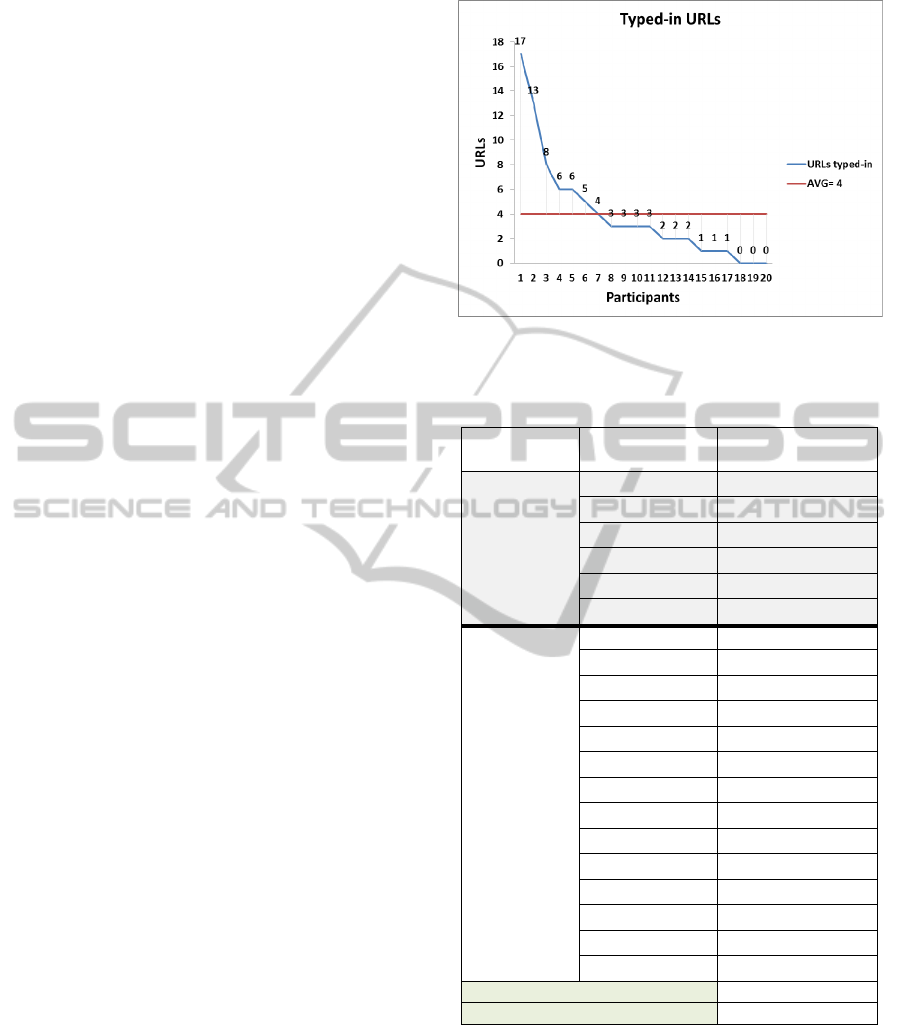

3.4.1 Using Typed-in URLs

The analysis of the data took the number of URLs

participants typed in to start searching for the task

requirements as a distinguishing factor between

orienteering and teleporting behaviour users. Based

on the average URLs typed in, 70% of the study

participants (14 users) were identified to have

followed teleporting behaviour to accomplish the

tasks. Only 30% (six users) were identified to have

followed orienteering behaviour. The difference

between the two proportions of participants was

significant according to the z-test results (z=1.96,

p<0.03). The actual data regarding the typed-in

URLs from the study are shown in Figures 1 and

Table 1. Six users who typed-in more URLs (above

average) were considered teleporting behaviour

users while the remaining users were considered

orienteering behaviour users. Due the fact that the

average URLs typed in did not draw a clear line

between two completely different kinds of behaviour

based on the data in the study, the analysis went to a

different criterion and the number of queries

submitted was tried as a distinguishing factor

between the two kinds of search behaviour.

3.4.2 Using Submitted Queries

The second factor used to determine which

proportion of participants followed which kind of

search behaviour during the study was the number of

queries submitted for accomplishing the tasks. As

shown

in

Figure

2

and further illustrated in

Table

2,

Figure 1: URLs typed-in by users to start searching for

information.

Table 1. Typed-in URLs.

Type of

behaviour

Participant

Number of URLs

typed in

participants

identified as

orienteering

behaviour

users

P2

17

P10

13

P11

8

P1

6

P20

6

P3

5

participants

identified as

teleporting

behaviour

users

P14

4

P8

3

P12

3

P13

3

P15

3

P6

2

P17

2

P8

2

P7

1

P9

1

P19

1

P4

0

P5

0

P16

0

࢞

ഥ

4

s 4.3

by taking the average number of queries submitted

during the study as a distinguishing factor, half of

the participants were considered as orienteering

behaviour users while the other half as teleporting

behaviour users. As a result, the two groups

resulting from using the number of queries

submitted as a distinguishing factor did not agree

with the two groups that resulted from using the

number of typed-in URLs. The analysis used the

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

326

average number of queries to distinguish users with

the two types of search behaviour which was not a

reliable choice due to the closeness of the numbers

of queries in each group to the average.

Table 2: Queries submitted during the study.

Type of

behaviour

Participant

Number of queries

submitted

participants

identified as

teleporting

behaviour

users

P4 23

P7 19

P10 15

P11 15

P6 13

P20 9

P5 8

P8 8

P9 8

P17 8

participants

identified as

orienteering

behaviour

users

P18 7

P19 6

P13 5

P15 5

P12 4

P16 4

P3 3

P1 1

P2 0

P14 0

Since the analysis yielded different

categorization in the case of using search queries as

an alternative to URLs typed in by the user, the

number of links followed by users in the latter case

was considered for analysis. The reason why the

number of links followed on the Web hierarchy was

considered in the case of using search queries only

and not in the case of URLs typed in is the number

of participants that would result from the

classification. In the case of using URLs typed in,

the number of orienteering behaviour users turned

out to be too small (only six participants). The use of

such small group may yield insignificant findings

when taking a step further in the analysis by

involving the links followed on the Web hierarchy

during the study. However, the use of queries

submitted as a distinguishing factor between

orienteering and teleporting behaviour users created

two similar groups (10 participants in each).

Therefore, it was selected with the analysis of linked

followed.

3.4.3 Number of Links Followed

Furthermore, by looking at the number of links each

group (orienteering or teleporting) followed on the

Web during the study, there was almost no

difference between the two groups of participants

distinguished by query submissions (ANOVA,

F(1,18)=1.81, p=0.19) as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Links followed by users: the case of using search

queries.

A

bove avera

g

e queries

(Teleporting)

Below avera

g

e

queries

Par

t

ici

p

an

t

lin

k

s

Par

t

ici

p

an

t

lin

k

s

P4 84 P18 61

P7 46 P19 60

P10 28 P13 73

P11 77 P15 22

P6 41 P12 2

P20 25 P16 22

P5 90 P3 53

P8 34 P1 11

P9 76 P2 42

P17 49 P14 57

࢞

ഥ

55

࢞

ഥ

40.3

s 24.4 s 24.3

ANOVA

,

f

=1

.

81

,

p

=

0

.

19

This finding indicates that: either users’

behaviour had characteristics of both orienteering

and teleporting search; or the average number of

search queries did not suffice for distinguishing the

‘expected’ two groups of users. Theoretically,

orienteering behaviour users submit fewer queries

than teleporting behaviour users. The difference was

between the number of queries submitted by the two

groups was significant according to a single-factor

ANOVA (F(1,18)=23.82, p<0.0002). Nonetheless,

the difference with regard to the number of links

followed was not significant.

3.4.4 Measuring Correlations

To further ensure that the user search behaviour was

hard to identify in the case of Web information

gathering tasks in the study, the analysis of the data

involved measuring the correlation between the

number of typed-in URLs and the number of queries

submitted by the study participants. We used the

Pearson Product Moment correlation test. We

considered measuring the correlation between

queries submitted and URLs typed in for all users at

first and then we followed by measuring the

correlations for each group of users identified as

either orienteering or teleporting users using the

WEBINFORMATIONGATHERINGTASKSANDTHEUSERSEARCHBEHAVIOUR

327

number of typed-in URLs and then using the number

of queries submitted.

The results concerning the correlation between

typed-in URLs and queries submitted during the

study for the entire group of users showed that there

was a very strong positive correlation between the

two groups of data (r=0.95, p<0.00001). Please refer

to Tables 1 and 2 for data. This relationship

contradicts the expected since a strong positive

correlation means that the more queries users

submitted, the more URLs they typed in while

gathering the information. This can be related to the

nature of the user and their activities during the

study. However, it is hard to distinguish one kind of

behaviour or the other as a result of this relationship.

For further assurance, we tackled the issue from a

different perspective by considering that there

actually exist two groups of users with two different

types of behaviour. Those two groups are first

distinguished by the number of URLs typed in, and

second by the number of queries submitted.

Table 4: Pearson (r) correlation test results in the case of

using typed-in URLs (teleporting).

Teleportin

g

Partici

p

ants

Queries

submitted

URLs typed-in

P14 0 4

P8 3 3

P12 1 3

P13 2 3

P15 2 3

P6 6 2

P17 3 2

P18 3 2

P7 13 1

P9 3 1

P19 2 1

P4 17 0

P5 4 0

P16 1 0

Pearson Product Moment ( r = -0.5, p<0.07 )

The results of the Pearson test shown in Table 4

indicate that there was a moderate relationship

between the number of URLs typed in and the

number of queries submitted with inverse

association between the two variables. The

participants shown in Table 4 are those initially

identified as teleporting behaviour users using the

number of typed-in URLs. For orienteering

behaviour users, the results of the Pearson test are

shown in Table 5. Those results indicate that almost

no correlation exists between the queries submitted

and the URLs typed-in.

Table 5: Pearson (r) correlation test results in the case of

using typed-in URLs (orienteering).

Orienteerin

g

Partici

p

ants

Queries

submitted

URLs typed-in

P2 0 17

P10 8 13

P11 6 8

P1 0 6

P20 5 6

P3 1 5

Pearson Product Moment (r = 0.04, p<0.94)

Table 6: Pearson (r) correlation test results in the case of

using submitted queries (teleporting).

Teleportin

g

p

artici

p

ants

Queries

submitted

URLs t

y

ped

in

P4 23 0

P7 19 1

P10 15 13

P11 15 8

P6 13 2

P20 9 6

P5 8 0

P8 8 3

P9 8 1

P17 8 2

Pearson Product Moment (r=0.04, p<0.91)

The analysis went to the use of the number of

queries to decide on the two groups of users

expected to follow one kind of behaviour or the

other. The data is shown in Tables 6 and 7. There

was almost a zero correlation between the submitted

queries and the typed-in URLs in the case of

participants identified as teleporting behaviour users

using the number of queries submitted as a

distinguishing factor (Table 6). In the case of

orienteering behaviour users identified also using the

number of queries submitted, the correlation was

strong indicating that an inverse relationship existed

(Table 7). However, this was only for half the

number of participants since in the case of the rest of

participants the correlation was close to zero.

The use of the correlation tests was a different

investigation step to ensure that the search behaviour

of the users in the study—while performing the

given information gathering tasks—was hard to

identify as either orienteering or teleporting. To this

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

328

Table 7: Pearson (r) correlation test results in the case of

using submitted queries (orienteering).

Orienteerin

g

p

artici

p

ants

Queries

submitted

URLs t

y

ped

in

P18 7

2

P19 6

1

P13 5

3

P15 5

3

P12 4

3

P16 4

0

P3 3

5

P1 1

6

P2 0

17

P14 0

4

Pearson Product Moment (r= -0.67, p<0.04)

point, the findings indicate that users’ search

behaviour may have had characteristics of both

orienteering and teleporting behaviours. However,

the use of averages (URLs typed in or queries

submitted) may not be sufficient. For example, it

might have not been invalid to put a user who

submitted seven queries (too close to the average of

eight queries) in the section of orienteering

behaviour users only because of a one-query

difference. Therefore, we selected another portion of

users in the study that is not centred around the

mean (i.e. outliers) even though we expected not to

have enough participants in groups categorized as

outliers.

3.4.5 Using Outliers with Correlations

Even though the use of correlations between queries

submitted and URLs typed-in by users during the

study further demonstrated that it was hard to draw a

line between orienteering and teleporting behaviour

users in the study, we took the investigation a step

further. In this step, the outliers in both cases: the

typed-in URLs and the queries submitted during the

study were considered.

In the case of using typed-in URLs, the outliers

were taken apart from the rest of the data by

considering numbers of URLs greater than 1.5 the

upper quartile (from Tables 1) and numbers of URLs

less than 1.5 the lower quartile. The results of this

selection are shown in Table 8. This table contains

the outliers with respect to the number of URLs

typed-in on both sides (shaded for clarification). The

table also contains the number of queries submitted

by each participant and the number of links followed

on the Web hierarchy.

Table 8: Outliers data (typed-in URLs).

Participant

Typed-in

URLs

Submitted

Queries

Links

Followed

P16 0 4 22

P5 0 8 90

P4 0 23 84

P19 1 6 60

P9 1 8 76

P7 1 19 46

P11 8 15 77

P10 13 15 28

P2 17 0 42

To ensure whether one type of behaviour or the

other (orienteering/teleporting) was followed, three

correlations were computed using Pearson Product

Moment. The correlation between the number of

typed-in URLs and the number of submitted queries

turned out to be weak and negative (r = -0.25,

p=0.51). The correlation between the number of

typed-in URLs and followed links was also weak

(r=0.39, p=0.29). The correlation between the

submitted queries and the followed links was weak

(r=0.29 and p=0.44).

The results show that there was no indication of

any specific type of behaviour by any group of

users. The weak correlations demonstrate that no

relationship can be explained by any of the factors

involved in the correlations except for the

relationship between queries submitted and links

followed which turned out to be weak. Users who

follow teleporting behaviour by relying on query

submissions usually tend to follow fewer links on

the hierarchies of websites than users who start

searching by typing in URLs. However, users who

relied on typing in URLs were not shown to have

made a significant use of the strategy of following

link hierarchies on the Web as shown by the test

results.

Furthermore, the analysis considered the outliers

in the case of using the number of queries submitted

by users during the study. The results are shown in

Table 9. The table contains the number of queries

(for outliers only) submitted by participants

associated with the URLs typed-in and links

followed for each participant. The correlations

between each two of the three factors were

computed using Pearson Product Moment. The

results showed that the correlation between the

number of submitted queries and typed-in URLs was

weak (r=0.41, p=0.31). The correlation between the

WEBINFORMATIONGATHERINGTASKSANDTHEUSERSEARCHBEHAVIOUR

329

submitted queries and the followed links was

moderate and positive (r=0.57, p=0.14). The

correlation between the typed-in URLs and the

followed links was weak and negative (r=-0.25,

p=0.55).

Table 9: Outlier data (submitted queries).

Participant

Submitted

Queries

Typed-in

URLs

Followed

Links

P4 23 0 84

P7 19 1 46

P10 15 13 28

P11 15 8 77

P3 3 5 5

P1 1 6 6

P2 0 17 42

P14 0 4 57

Orienteering behaviour users rely usually on

typing URLs for starting search for information on

the Web. They also follow links on Web pages to

locate information of the interest. The weak and

negative correlation between URLs typed in and

links followed contradicts the definition of

orienteering behaviour. Actually, a stronger

relationship can be seen in the correlation between

submitted queries and followed links, which is

contradictory to the teleporting search behaviour

definition. The only correlation that agrees with the

definitions of search behaviours (orienteering vs.

teleporting) is the correlation between queries

submitted and URLs typed in. Nonetheless, it was a

weak relationship.

4 DISCUSSION

The study used the number of typed-in URLs, the

number of search queries submitted, and the number

of links followed on the Web hierarchy during the

tasks in order to identify the type of behaviour users

followed while performing information gathering

tasks during the study. The results showed that

neither factor was sufficient to make a clear

distinction between the two groups of users with

respect to the search behaviour during the tasks. To

further ensure that no clear signs of either behaviour

could be identified among participants in the study,

the correlation between the typed-in URLs and the

search queries submitted during the study was

measured for the entire group of users, the two

groups distinguished by the number of URLs typed

in, and the two groups distinguished by the number

of queries submitted.

According to the results of the correlation tests, it

was hard to identify which group of participants

followed which type of search behaviour while

performing the information gathering tasks given

during the study. The initial idea behind orienteering

and teleporting behaviours is that one is different

from the other. Users who follow orienteering

behaviour are those who type-in URLs more often

and follow hyperlink connectivity on the Web to

search for information. Users who follow teleporting

behaviour usually rely on the submission of search

queries in order to find information. This type of

users hardly starts searching at a certain URL and

barely follows links on Web pages using a series of

clicks to locate information.

Every time the analysis of the study data

considered one criterion to make a distinction

between the two kinds of behaviour amongst the

study participants, it was hard to conclude on which

group followed which kind of search behaviour. The

results of the analysis indicate that activities users

perform during this kind of task belong to both kinds

of behaviour. Therefore, the type of search

behaviour had no effect on the task and was not

affected by the nature of the Web information

gathering tasks.

Even with the selection of a subset of users that

represented only the outliers in the cases of typed-in

URLs and submitted queries, the correlations

computed among submitted queries, typed-in URLs,

and followed links did not demonstrate that one kind

of search behaviour was dominant in the case of any

group of participants. Interestingly, the relationship

between query submission and following links on

the Web was moderate showing that the same users

had two features from two different kinds of search

behaviour (Table 8).

As a result of the study, any support for

information gathering tasks in terms of building

tools for the task should consider both characteristics

of the two kinds of behaviour. The design should

take into account that users gathering information on

the Web using the current available tools may adopt

varied strategies and use several techniques and

features to accomplish the goal of the task. Users

submit queries at different levels of frequency, open

browser tabs and windows, compare information,

collect information from both actively open Web

pages in the browser and search hits’ summaries,

and use different tools to accomplish the task. They

use search engines and type in URLs to start

searching on the Web hierarchy by following links

on Web pages and sites.

WEBIST2012-8thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

330

In future designs of Web tools intended for

information gathering, support should be provided

for allowing users to open multiple URLs in a way

that eases the information comparison process with

which users usually have difficulties when using

browser tabs and windows. Support should also be

provided to users submitting several queries

simultaneously to compare result hit summaries.

Those users used browser tabs and windows and lost

track of information on several occasions in the

study. Moreover, the design should support multiple

activities on the same display for users typing-in

URLs and trying to follow links on Web pages as

they continue to gather information. Finally, the

design of Web information gathering tools should

consider both searching by following the hierarchy

of the Web graph and by submitting search queries

in an efficient manner so that the number of times

users have to switch among applications and tools is

minimized. The significance of the Web information

gathering task necessitates that further work is

needed since current applications including the Web

browser suffer from several pitfalls that degrade the

user’s ability to effectively perform information

gathering tasks on the Web.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The paper discussed the results of a part of a user

study that was intended to reveal the kinds of

behaviour Web users adopt while gathering Web

information. The study results showed that the

search approach for gathering the information

required in the tasks had several characteristics of

both kinds of behaviour. This conclusion reflects

two important points. First, this kind of task is

complicated and requires much effort with several

kinds of activities involved. Second, support is

needed for several activities in the task of Web

information gathering including searching by both

following link hierarchies and frequent query

submission. The support is also required for

comparing information and decision making during

the task.

REFERENCES

Alhenshiri, A., Watters, C., and Shepherd, M. 2012.

Building support for web information gathering tasks,

A paper submitted to the Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences (HICSS45), (Grand

Wailea, Maui, Hawaii, USA, January 04-07), 2012, to

appear.

Alhenshiri, A., Watters, C., and Shepherd, M. 2010.

Improving web search for information gathering:

visualization in effect. In Proceedings of the 4th

Workshop on Human-Computer Interaction and

Information Retrieval (HCIR2010), New Brunswick,

NJ, USA, 1-6.

Amin, A. 2009. Establishing requirements for information

gathering tasks. TCDL Bulletin of IEEE Technical

Committee on Digital Libraries, Volume 5, Issue 2,

ISSN 1937-7266.

Broder, A. 2009. A Taxonomy of web search. ACM

SIGIR Forum, vol 36, issue 2, 2-10.

Choo, C., Detlor, B., and Turnbull, D. 1998. A behavioral

model of information seeking on the Web--preliminary

results of a study of how managers and IT specialists

use the Web. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of

the American Society for Information Science,

Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25-29.

Ellis, D., Cox, D., and Hall, K. 1993. A Comparison of the

information seeking patterns of researchers in the

physical and social sciences. J. Documentation, vol.

49, issue 4, 356-369.

Kellar, M., Watters, C., and Shepherd, M. 2007. A field

study characterizing web-based information-seeking

tasks. J. the American Society for Information Science

and Technology, vol. 58, issue 7, 999-1018.

Kules, B., Capra, R., and Sierra, T. 2009. What do

exploratory searchers look at in a faceted search

interface? In Proceedings of the 9th ACM/IEEE-CS

Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, Austin, TX,

USA, 313-322.

Marchionini, G. 1997. Information seeking in electronic

environments. Cambridge University Press, New

York.

Rose, D., and Levinson, D. 2004. Understanding user

goals in web search. In Proceedings of the 13th

International Conference on World Wide Web, New

York, NY, USA, 13-19.

Santini, M. 2006. Interpreting genre evolution on the Web.

In Proceedings of the EACL 2006 Workshop, Trento,

32-40.

Sellen, A., Murphy, R., and Shaw, K. 2002. How

knowledge workers use the Web. In Proceedings of

the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA,

227-234.

Teevan, J., Alvarado, C., Ackerman, M., and Karger, D.

2004. The perfect search engine is not enough: a study

of orienteering behaviour in directed search. In

Proceedings of the 2004Conference on Human Factors

in Computing Systems, Vienna, Austria, 415-422.

Wilson, T., and Walsh, C. 1996. Information behaviour:

an interdisciplinary perspective. British Library

Research and Innovation Report 10, University of

Sheffield, Department of Information Studies,

Sheffield, UK.

WEBINFORMATIONGATHERINGTASKSANDTHEUSERSEARCHBEHAVIOUR

331