OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-ASSISTED LANGUAGE LEARNING

FOR EUROPEAN PORTUGUESE AT L

2

F

Thomas Pellegrini

1

, Wang Ling

1,2,3

, Andr´e Silva

1

, Rui Correia

1,2,3

, Isabel Trancoso

1,2

,

Jorge Baptista

4

and Nuno Mamede

1,2

1

Instituto de Engenharia de Sistemas e Computadores - Investigac¸˜ao e Desenvolvimento, Lisbon, Portugal

2

Instituto Superior T´ecnico, Lisbon, Portugal

3

Language Technologies Institute, Carneggie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, U.S.A.

4

Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

Keywords:

CALL, Portuguese, Vocabulary Acquisition, Listening Comprehension, Serious Games, Broadcast News.

Abstract:

In this paper, we give an overview of our research in Computer-Assisted Language Learning for European Por-

tuguese, to show how our long-time experience in spoken language processing allowed to propose multimedia

documents as learning material. Beside a reading activity module that provides learners with individualized

readings from a digital libray, Web-based serious game were introduced to cover aspects of listening, reading,

and writing skills. One fundamental aspect of all our tools remains in the fully-automatic generation of the

curriculum. This is very valuable for teachers, saving them time in search for motivating materials of appro-

priate quality, level and topic. A Web portal was recently created to make all our tools publicly available at

http://call.l2f.inesc-id.pt/reap.public.

1 INTRODUCTION

Our research in Computer-Assisted Language Learn-

ing (CALL) started in 2009 in the context of a joint re-

search program between Portuguese universities and

the Carneggie Mellon University. The first effort was

to port to Portuguese the vocabulary learning tutoring

system developedat the Language TechnologiesInsti-

tute (LTI) for English

1

. The system initially focused

on vocabulary learning by presenting to students read-

ing material with target vocabulary words in context

(Heilman et al., 2006).

Once the text-based reading activity system was

adapted, new functionalities were included, in par-

ticular Text-To-Speech (TTS) features, rich transcrip-

tions provided by our automatic speech recognition

(ASR) engine and its post-processing modules, and

Machine Translation (MT) within a game. The basic

idea was to benefit from our long-time experience in

spoken language processing to enhance the features

of the system.

European Portuguese (EP) L2 learners often state

that their listening skills cannot cope with sponta-

neous speech. In fact, one well-known character-

1

http://reap.cs.cmu.edu, (last visited in February 2012)

istic of EP that distinguishes it from Brazilian Por-

tuguese in particular, is the strong use of vowel re-

duction and simplification of consonantal clusters,

both within words and across word boundaries (Cruz-

Ferreira, 2009). Hence, the practice of listening com-

prehension appeared to be a very important feature

to explore. With the growing interest in using seri-

ous games to motivate learners (Sørensen and Meyer,

2007), we decided to develop some games to be in-

cluded in the platform.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2

presents related work with some examples of CALL

interfaces and games. Section 3 describes the main

vocabulary learning platform. The introduction of

multimedia documents, in particular broadcast news

shows, is explained in Section 4, with the description

of a BN browsing tool and vocabulary perception se-

rious games. Finally, complementary serious games

are presented in Section 5.

2 RELATED WORK

Our CALL system is centered in Multimedia and In-

ternet, resulting from the shift to globalization, where

538

Pellegrini T., Ling W., Silva A., Correia R., Trancoso I., Baptista J. and Mamede N..

OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-ASSISTED LANGUAGE LEARNING FOR EUROPEAN PORTUGUESE AT L2F.

DOI: 10.5220/0003921505380543

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (SGoCSL-2012), pages 538-543

ISBN: 978-989-8565-07-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the teachers turn into facilitators instead of being the

source of knowledge, and the students should inter-

pret and organize the information given in an active

way. A number of recent projects have taken similar

approaches to provide language learners with authen-

tic texts. WERTi (Meurers et al., 2010) is an intel-

ligent automatic workbook that uses texts from the

Web to increase knowledge of English grammatical

forms and functions. READ-X (Miltsakaki, 2009)

is a tool for finding texts at specified reading levels

that also performs a classification per area of interest.

TAGARELA (Bailey and Meurers, 2008) is an intelli-

gent computer-assisted language learning system that

provides opportunities to practice reading, listening

and writing skills.

Beside the use of texts to develop reading skills,

multimedia documents, and videos in particular, are

a priviledged medium to practice listening compre-

hension and vocabulary acquisition. Secules et al.

(Secules et al., 1992) showed how listening compre-

hension skills improve when using video-based con-

tents on French students. In (Brett, 1995), the au-

thor showed that authentic video materials with sub-

titles can increase the students’ motivation to engage

in these types of tasks.

Recently, games have gained strong interest in the

CALL community to support L2 acquisition. These

games are referred to as serious games, being charac-

terized by an educational goal supported by entertain-

ment features (Sørensen and Meyer, 2007). Combin-

ing recent multimedia curriculum and serious games

may render the tools more appealing and learning ef-

fective.

3 THE WEB AS AN OPEN

CORPUS

At first login to the reading activity module, the stu-

dent is given a pre-test, in which the interface shows

a target word list extracted from the Portuguese Aca-

demic Word List (P-AWL) (Baptista et al., 2010), and

they are asked to choose the ones they know, in or-

der to assign one of the 12 school levels. The current

version of P-AWL contains the inflections of about

2K different lemmas, totaling 33.3K words. Tar-

get words are assigned to each student according to

their estimated level. Students may also define which

topics they are interested in. Student-specific target

word lists and preferred topics render the system more

student-adapted. Different students will have differ-

ent interactions with the system.

The main reading activity component of the Web

platform, which was also the first developed compo-

nent, provides the students with real texts, which were

automatically retrieved from the Web. The main doc-

ument repository is the ClueWeb09 corpus. This is

a collection of over 1 billion Web pages (5 TB com-

pressed, 25 TB uncompressed), created by LTI

2

. This

corpus contains texts in 10 different languages (such

as Arabic, English, Portuguese or Spanish), compiled

for research on speech and language technology. In

the specific case of the Portuguese section of this cor-

pus, it includes more than 37.5 million pages, all re-

trieved in 2009. This subset of documents (about 160

GB compressed) constitutes the corpus currently be-

ing used in our project. The average document size is

3,000 characters.

At each access to the individual reading activ-

ity platform, a list of five texts is presented. A

search module is responsible for retrieving from the

Web-based corpus the texts satisfying particular ped-

agogical constraints such as readability level and text

length, and containing words from the target list that

students should learn. It is also responsible for match-

ing these documents with the student preferences in

terms of topic. This filtering stage is a very valuable

tool for teachers, saving them time in search for mo-

tivating materials of appropriate quality, readability

and topic.

The list of topics includes ten labels, such as Econ-

omy, Education, Health, Politics, Sports, etc. We use

the same topic indexer as the one used in our broad-

cast news processing pipeline (Amaral et al., 2007).

A topic likelihood is compared to the corresponding

non-topic likelihood, and given a threshold that was

estimated for each topic, a classification decision is

taken. With this method, several topic labels may

be assigned to a single text. Concerning the read-

ability level, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are

used to estimate the grade level of the texts with lex-

ical features as input, such as statistics of word uni-

grams (Marujo et al., 2009).

During a reading session, the target words are

highlighted in the texts and the student can search

for the meaning of the words by clicking on them or

by using the search field of the system. The read-

ing session is followed by a series of multiple-choice

definition questions and cloze (fill-in-the-blank) sen-

tences about the words that were highlighted These

exercises are automatically generated based on a set

of 6k sentences that were selected and adapted by lin-

guists (Correia et al., 2010).

2

http://boston.lti.cs.cmu.edu/Data/clueweb09 (last vis-

ited in December 2010)

OVERVIEWOFCOMPUTER-ASSISTEDLANGUAGELEARNINGFOREUROPEANPORTUGUESEATL2F

539

4 MULTIMEDIA DOCUMENTS

AS LEARNING MATERIAL

Our first effort to propose multimedia documents con-

sisted of including a set of audio books. Nevertheless,

the number of books we included was limited due to

author copyright restrictions. An alternativewas to in-

troduce broadcast news (BN) videos. A large repos-

itory of BN shows has been daily stored and auto-

matically transcribed since 2009. BN material allows

to provide the learners with very recent curriculum,

with a wide choice of short stories on different top-

ics and with the added value of videos. Another early

initiative consisted of integrating our real-time Text-

To-Speech engine in the reading activity module de-

scribed in the previous section. The reader may select

words from the text to listen to a synthesized audio

version.

So far, we developed two components that use BN

shows: a listening/reading activity page, and several

vocabulary perception games providing isolated sen-

tences extracted from BN shows.

4.1 Enriched Broadcast News Videos

Panel

The BN videos need to be automatically segmented,

transcribed and indexed in order to prepare and se-

lect relevant excerpts. The processing pipeline con-

sists of removing the jingles that usually start and

end the news shows, segmenting the audio stream

into single-speaker homogeneous speech segments,

and transcribing the segments automatically with our

in-house automatic speech recognition (ASR) sys-

tem (Neto et al., 2008). Further modules are then ap-

plied to include punctuation, capitalization, and mul-

tiple topic labels. The topic classifier is the same tool

as the one used with the Web texts of the reading ac-

tivity component described in Section 3.

The output of the BN pipeline is comprised of sto-

ries with about 300 words each on average. A filter is

applied to automatically estimate the readability level

of the stories, from grade 5 to grade 12, with the same

classifier as the one described in Section 3. It was

found that the language level of the stories span over

the 7

th

and the 11

th

grades, with an average corre-

sponding to the 8

th

grade (Lopes et al., 2010). After

the processing pipelineand the levelclassification, the

filtered stories are displayed on a single Web page,

showing the video excerpts with their automatic tran-

scriptions.

4.2 Vocabulary Perception Serious

Games

As mentioned in the introduction, EP listening per-

ception skills are hard to master for L2 learners. At-

tempting to combine the rich diversity of our BN

repository with the motivating aspects of games, we

developed “vocabulary perception” games. In these

games, the learner is asked to listen to an utterance us-

ing only audio or along with a video clip, and then the

sentence should be reconstructed by choosing words

from lists containing the correct words and some dis-

tractors. Our main objective was to give realistic

speech for the learners to get used to the sounds and

the pronunciation of native speakers. Figure 1 shows

one of the game interfaces.

All the exercises are generated in a fully-

automatic way. A filtering is needed to discard sen-

tences with probably misrecognized words. A se-

quence of five filters was designed to select the sen-

tences: sentence length smaller than 10 words, high

ASR confidence measures, syntactic completeness (at

least one verb and one common name), large signal-

to-noise ratio, descending pitch slope in the sentence

boundaries (neutral declaratives). Finally, the distrac-

tors are also automatically generated, with two com-

plementary techniques, either based on the confusion

networks produced by the recognizer, or on phonetic

distances (Pellegrini et al., 2011).

In (Correia et al., 2011), the best features for the

games were explored by submitting a set of 18 ex-

ercises ending with a questionnaire to EP L2 speak-

ers with various proficiency levels. Preference was

given to: video in all the exercises, recent content and

preferably anchor speech. A search feature was also

proposed, allowing the player to search for a phrase

into the BN repository. This feature was also appre-

ciated, but some search suggestions should be pro-

vided. A karaoke feature was well appreciated, allow-

ing the user to watch the video with the corresponding

transcription while the words are being highlighted as

they are spoken. Finally, slowing down the speech

rate was a feature used by the subjects with the lowest

proficiency.

5 OTHER SERIOUS GAMES

5.1 Vocabulary Learning Game

Lexical Mahjong proposes a set of exercises where

the student has to establish a correspondence between

a lemma and a definition. The list of target words

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

540

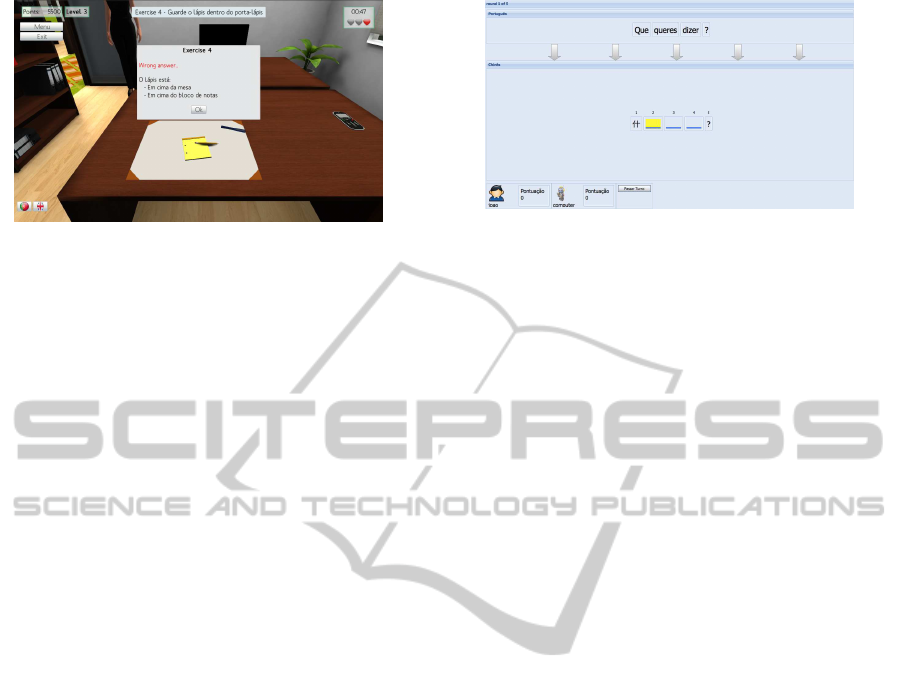

Figure 1: Tick interface of the vocabulary perception game.

came from P-AWL (Baptista et al., 2010) and the def-

initions are taken from the Infop´edia

3

. A set of filters

selects the definitions: (1) definitions containing cog-

nates of the target word are discarded, since they are

an obvious cue to the student; (2) only definitions of

more than one word (to avoid similarities with syn-

onyms’ exercises) and less than 150 words (to avoid

very long definitions) are considered; (3) characters

that hinder the understanding of a given definition are

removed (e.g. numbering of definitions, semicolon,

cardinal, etc.); (4) the learning level of the words in

the definition must be equal to or less than the level of

the exercise and that of the target word it corresponds

to (Lopes et al., 2010).

Definitions were also classified according to their

difficulty level. Three levels were considered: begin-

ners, intermediate and advanced. As the system is

student-oriented, the word-definition pairs are chosen

according to the student profile, taking into considera-

tion: (i) the student’s level, influencing the number of

word-definition pairs that are presented to the student;

it also determines the difficulty level of the defini-

tions presented; (ii) the student’s history, determining

which words are presented to the student, by showing

words that the student probably does not know yet.

The Lexical Mahjong exercises already require

some knowledge of Portuguese as they call upon more

advanced language contents. Due to the difficulties in

gathering a test group with these features, evaluation

of the game was conducted on a group of Portuguese

native speakers in the 3rd and 4th grade (Group 1),

who, in spite of their knowledge of Portuguese as

mother language, still have limited vocabulary. The

same test was also performed with a control group,

comprised of native speakers with at least a college

degree (Group 2). Thus, 45 subjects performed this

exercise, 18 in Group 1 and 31 in Group 2. Each

3

http://www.infopedia.pt (last visited in December

2010)

player was given three sets of words from each dif-

ficulty level. More than 77% of the users found the

system easy to use, while only 39% needed to use the

“Help” button. Group 2 obtained better results, with

a performance of 84.0% (standard deviation = 6.6%),

while the users from Group 1 made more errors and

just attained a performance of 54.0% (sd=12.4%).

The error rate progression for each exercise showed

that in both groups the more difficult the exercises,

the more mistakes the players do. This result seems

to confirm the adequacy of the strategy here followed

for distinguishing the level of the definitions from the

dictionary entry of each target word. It may also con-

tribute to devise automatic assessment strategies for

second language learners.

5.2 Verbs and Spatial Prepositions 3D

Game

REAP Pict

´

orico is a serious game which aims at

teaching the verbs and prepositions used to describe

the spatial relation of objects. Exercises are solved

in a game environment making use of a 3D scenario

in order to further capture the student’s interest. The

Unity 3D game engine

4

, was chosen to implement the

game (Ribeiro et al., 2010).

In the game, the player controls an avatar through

first-person perspective mainly. The scenario consists

of an office composed of 5 different rooms, and in

each room there are several exercises to be completed.

The exercises consist in asking the student to move an

object in the scenario to new positions with the use

of the mouse, according to a given instruction. For

example: Coloque o objecto A em cima do objecto B

(Put the object A on top of the object B). Answers

given by the students are automatically evaluated by

our game (Silva et al., 2011).

When the player does not position an object in the

right place, the game describes the action that was

made and the one that should have been made. Fig-

ure 2 shows an example of informative feedback to

explain to the player that he wrongly positioned the

pen over the table and over the notepad instead of in-

side the pencil holder. Hence, the students may also

learn from their mistakes by reading spatial verbs and

prepositions that may be different from the ones used

in the exercise instructions.

A first evaluation of the game was conducted. A

total of 14 students from the Portuguese as Second

Language (PSL) course of the University of Algarve

played with the application and answered a survey. In

terms of the interaction with the game – moving ob-

4

http://unity3d.com/ (last visited in November 2011)

OVERVIEWOFCOMPUTER-ASSISTEDLANGUAGELEARNINGFOREUROPEANPORTUGUESEATL2F

541

Figure 2: Screen shot of the 3D pictorial game. The player

is asked to complete actions involving spatial verbs and

prepositions.

jects and controlling the avatar –, those who stated

that the control of the avatar was easy, were also

those who had less trouble moving objects around,

and vice-versa. It appeared that learning how to play

the game was not at all considered by most students

as a barrier in their learning experience. The survey

also asked the students to estimate how much they

had learned. Their answers were very encouraging.

25% stated that they might have learned more with the

game than with a traditional class, while 75% stated

they might have learned the same. In general, students

were satisfied (50%) or very satisfied (25%) with the

game.

5.3 Translation Game

This competitive language translation game aims at

improving students vocabulary and writing skills. An

automated agent is employed as an opponent in or-

der to improve the user’s motivation and maintain the

user focused. The game can currently be played with

the language pairs English-French, English-Chinese,

and Portuguese-Chinese, but it can easily be adapted

to other language pairs for which one has a parallel

corpus and an MT engine.

The exercises were created by processing the

BTEC and DIALOG test corpus from the IWSLT

2010 evaluation. The Portuguese-Chinese language

exercises were built by using the DIALOG English-

Chinese dataset. A subset was manually translated

from English to Portuguese since the corpus does not

provide Portuguese-Chinese sentence pairs directly.

The game only allows a single translation, selected

among a set of manually created references. The

agent’s actions are based on the output of a statisti-

cal machine translation system. The agent has a rep-

resentation of its current state, and a Markov process

that determines how that state evolves for each action

the agent or the player can perform. This resembles

the process used in chess playing agents, where the

agent has to think multiple moves ahead to determine

Figure 3: Screen shot of the translation game.

the next action.

Each game is composed by a number of rounds.

In each round the system presents a sentence in

the source language (typically, the user’s native lan-

guage), and the corresponding sentence in the target

language with a number of hidden words (or charac-

ters, in the Chinese case), marked with an empty un-

derlined space. Players take turns to guess the words

that are hidden, proposing only one word at each turn.

Players are rewarded 20 points when they get the right

answer and penalized 5 points when they propose a

wrong answer. In each round, the hardest word to find

is marked in yellow, which is worth 40 points. Finally,

the player who guesses the last word completing the

sentence receives an additional 30 points.

Figure 3 shows a screen shot of this translation

game where the sentence “Que queres dizer?” is to be

translated into Mandarin. The target sentence shows

words in green (answered by the student) and in red

(answered by the agent). The bonus word has a yel-

low background.

An evaluation that was performed with 20 Por-

tuguese learners of Mandarin suggested that the sub-

jects were more focused and motivated when playing

against the agent rather than playing alone. Further-

more, the majority of students said that the system

helped them learn Mandarin and would like to use it

in the future. The system has a web-based implemen-

tation and is easily accessible by language learners.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we presented our CALL plat-

form, publicly available at http://call.l2f.inesc-

id.pt/reap.public. The first developed tool was an in-

dividual reading activity module that gives access to a

very large Web text corpus (about 37 million pages),

presented according to automatically estimated read-

ability levels and inferred topic labels. One of the

most innovative aspects of our platform remains in

the use of our speech and natural language processing

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

542

technologies to propose real-life multimedia docu-

ments as learning material. ASR and subsequent pro-

cessing modules are used to propose broadcast news

videos together with enriched transcriptions. TTS is

used to allow the learners to listen to any text seg-

ment of interest. Finally, our serious games comple-

ment the reading component: a vocabulary perception

game, a vocabulary learning game, a game to learn

spatial verbs and prepositions, and a translation game.

Hence, the platform covers three of the four major

skills: listening, reading, and writing skills. Cur-

rent research effort is devoted to further enhance our

tools with pronunciation aid modules to also cover the

speaking skill.

Evaluations were carried out with EP L2 learners.

These evaluations mainly concerned the features of

the modules and the games, in order to help choosing

the best ones. The user interest and satisfaction were

also evaluated, and very positive feedback was given

in general.

Further evaluations of learner performance are

needed to establish whether our modules and games

are conducive to actual learning. In particular, pre-

and post-tests are envisaged to study the impact of

our tools on the user’s learning experience. Further-

more, future work will include the testing of new fea-

tures in our modules and games, such as a synthesized

voice with control on the co-articulation effects and

the speech rate.

REFERENCES

Amaral, R., Meinedo, H., Caseiro, D., Trancoso, I., and

Neto, J. (2007). A Prototype System for Selective

Dissemination of Broadcast News in European Por-

tuguese. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal

Processing, page 11.

Bailey, S. and Meurers, D. (2008). Diagnosing meaning er-

rors in short answers to reading comprehension ques-

tions. In Proc. of the Third Workshop on Innovative

Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications,

pages 107–115, Morristown.

Baptista, J., Costa, N., Guerra, J., Zampieri, M., de Lur-

des Cabral, M., and Mamede, N. (2010). P-AWL:

Academic Word List for Portuguese. In Proc. PRO-

POR, pages 120–123, Porto Alegre.

Brett, P. (1995). Multimedia for listening comprehension:

The design of a multimedia-based resource for devel-

oping listening skills. System, 23(1):77–85.

Correia, R., Baptista, J., Mamede, N., Trancoso, I., and Es-

kenazi, M. (2010). Automatic Generation of Cloze

Question Distractors. In Proc. SLaTE, Tokyo.

Correia, R., Pellegrini, T., Eskenazi, M., Trancoso, I., Bap-

tista, J., and Mamede, N. (2011). Listening Compre-

hension Games for Portuguese: Exploring the Best

Features. In Proc. SLaTE, Venice.

Cruz-Ferreira, M. (2009). European Portuguese. Journal of

International Phonetic Association, 25:02:90–94.

Heilman, M., Collins-Thompson, K., Callan, J., and Es-

kenazi, M. (2006). Classroom Success of an Intelli-

gent Tutoring System for Lexical Practice and Read-

ing Comprehension. In Proc. Interspeech, pages 829–

832, Pittsburgh.

Lopes, J., Trancoso, I., Correia, R., Pellegrini, T., Meinedo,

H., Mamede, N., and Eskenazi, M. (2010). Multi-

media Learning Materials. In Proc. IEEE Workshop

on Spoken Language Technology SLT, pages 109–114,

Berkeley.

Marujo, L., Lopes, J., Mamede, N., Trancoso, I., Pino, J.,

Eskenazi, M., Baptista, J., and Viana, C. (2009). Port-

ing REAP to European Portuguese. In Proc. SLaTE,

pages 69–72, Birmingham.

Meurers, D., Ziai, R., Amaral, L., Boyd, A., Dimitrov, A.,

Metcalf, V., and Ott (2010). Enhancing Authentic

Web Pages for Language Learners. In Proc. of the

5th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building

Educational Applications, NAACL-HLT,Los Angeles.

Miltsakaki, E. (2009). Matching readers preferences and

reading skills with appropriate web texts. In Proc.

EACL, Athens.

Neto, J., Meinedo, H., Viveiros, M., Cassaca, R., Martins,

C., and Caseiro, D. (2008). Broadcast news subtitling

system in portuguese. In Proc. ICASSP 2008, Las Ve-

gas, USA.

Pellegrini, T., Correia, R., Trancoso, I., Baptista, J., and

Mamede, N. (2011). Automatic generation of listen-

ing comprehension learning material in European Por-

tuguese. In Proc. Interspeech, pages 1629–1632, Flo-

rence.

Ribeiro, C., Jepp, P., Pereira, J., and Fradinho, M. (2010).

Lessons Learnt in Building Serious Games and Vir-

tual Worlds for Competence Development. In Proc.

Workshop on Experimental Learning on Sustainable

Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering,

pages 52–62, Milano.

Secules, T., Herron, C., and Tomasello, M. (1992). The

effect of video context on foreign language learning.

Modern Language Journal, 76(4):480–490.

Silva, A., Mamede, N., Ferreira, A., Baptista, J., and Fer-

nandes, J. (2011). Towards a serious game for por-

tuguese learning. In Proc. 2nd International Con-

ference on Serious Games Development and Applica-

tions (SGDA 2011), volume 6944 of Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, pages 83–94. Springer-Verlag.

Sørensen, B. and Meyer, B. (2007). Serious Games in lan-

guage learning and teaching – a theoretical perspec-

tive. In Proc. Digital Games Research Association

Conference, pages 559–566.

OVERVIEWOFCOMPUTER-ASSISTEDLANGUAGELEARNINGFOREUROPEANPORTUGUESEATL2F

543