CAN A MEDIA ANNOTATION TOOL ENHANCE ONLINE

ENGAGEMENT WITH LEARNING?

A Multi-case Work-in-progress Report

Meg Colasante

1

and Josephine Lang

2

1

College of Science, Engineering and Health, RMIT University, La Trobe Street, Melbourne, Australia

2

School of Education, RMIT University, La Trobe Street, Melbourne, Australia

Keywords: Learning Engagement, Undergraduate Education, Multiple-case Study, Media Annotation, Video

Annotation, Emerging Educational Technology, Online Learning, E-learning, Multimedia Learning.

Abstract: The paper explores preliminary data of four cases in a larger study investigating the effects on learning of a

new educational technology called Media Annotation Tool (MAT). In particular, the paper focuses on

learning engagement with MAT and begins to raise questions about what factors promote or enhance

engagement. Drawing on the work of Kirkwood (2009), the authors analyse the type of educational

technology functions that were expressed through the ways teachers integrated the use of MAT into their

curriculum. Another factor explored in the paper is student engagement. Barkley’s (2010) theorising on the

complexity of student engagement for learning argues that engagement is where motivation and active

learning synergistically interact. Examining students’ reflections on their use of MAT, the authors identify

that while MAT offers active learning, motivation for the use of MAT may be a missing factor for some

disengaged students. This insight provides further themes to explore in further analysis of the project’s data.

1 INTRODUCTION

Advances in educational technology offer diverse

benefits for tertiary education students, such as

flexible anywhere-anytime learning. However, it is

not responsible to claim that any new educational

technology development is capable of learner benefits

without research and evaluation, and such research

and evaluation should include how the tool is actually

(and specifically) used to achieve learning by the

teachers and students. There are growing calls for

research studies that are based on inquiries that reflect

the complexity and “the more transformational effects

of e-learning, such as creating a distributed

community, and learning new genres of

communication and collaborative work practice”

(Andrews and Haythornthwaite 2007, p. 2).

This paper discusses a new educational

technology, ‘Media Annotation Tool’ (MAT), and

the current research project that is examining the

tool as integrated into several tertiary education

courses (subjects) spanning a range of disciplines.

The various classes formed cases in the multiple-

case study, including four undergraduate, one

postgraduate, and four vocational (TAFE/college)

classes. While extensive data (surveys, interviews

and learning artefacts) have been collected and data

analysis is well underway, this paper will focus on

the early findings from data across the four

undergraduate cases; that of chiropractic, medical

radiation, and two primary education classes: visual

arts and literacy.

Discussion on this particular data focuses on

learning engagement with MAT and begins to raise

questions about what factors promote or enhance

engagement with activities using the tool. This is in

acknowledgement that technology does not

singularly—in isolation of other factors—enhance

engagement for learning and/or improve learning

outcomes (Kirkwood, 2009). Student engagement

for learning is complex involving a “synergistic

interaction between motivation and active learning”

(Barkley, 2010, p. 8).

Kirkwood (2009) recognises that ICT has been

adopted in higher education to enable functions such

as: presentation on demand; interaction and

engagement with resources; dialogue between

learner-teacher and learner-learner; and generative

activity by students to use as evidence of learning.

455

Colasante M. and Lang J..

CAN A MEDIA ANNOTATION TOOL ENHANCE ONLINE ENGAGEMENT WITH LEARNING? - A Multi-case Work-in-progress Report.

DOI: 10.5220/0003965604550464

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (ESEeL-2012), pages 455-464

ISBN: 978-989-8565-07-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Kirkwood adds “There is the potential for ICT to

extend or even transform what can be realised in HE

teaching (Kirkwood, 2009, p. 108, his emphasis)”.

Significantly for the scrutiny of this project, he

highlights a disconnect in educational technology

between potential and actual learning benefits,

including engagement, and how “teachers and

learners don’t always get what they hope for”

(Kirkwood, 2009, p.109).

This paper is a preliminary look at the four

undergraduate cases for differentiation in indicators

of learning engagement with MAT, and seeks out

variables to offer points for further examination of

the project’s data.

2 WHAT IS ‘MAT’?

MAT is a media annotation tool designed to allow

students to engage actively with learning artefacts

represented in various media forms. Although being

trialled by a number of programs, the tool is still in

its first stage of development. The trial is allowing to

refine the use of video media in MAT for learning

and teaching; yet design work has occurred to enable

use of other media forms (audio, digital images and

text: Stage II; inverting work in MAT into a media-

rich report: Stage III).

What differentiates MAT from uploading a video

into other technology used in education, such as a

wiki, blog, YouTube, discussion board, etc., is that

instead of general comments in a single, linear

listing, or perhaps branching off in various

unstructured directions, MAT allows for notes or

conversations to be attached directly to various

selected pieces of artefact (media) under discussion

in a structured manner.

As presentational technology, MAT could be

dismissed as not capable of transforming learning

experiences compared to technology with primarily

communicative roles, such as idea sharing and co-

construction of knowledge (Lai, 2011). However,

MAT brings these cognitive and socio-constructive

processes together within one tool, giving students

opportunities to actively engage, discuss, and make

personal meaning of presentation material.

MAT helps to fill the gap that can be drawn from

the Sloan Consortium synthesis of research on the

effectiveness of online learning environments, which

draws upon the Community of Enquiry Model of

Rourke, Anderson, Garrison & Archer (2001; cited

in Swan 2004). Here it is inferred that online

interaction with content encourages more divergence

in thinking and discussion than face-to-face, while

face-to-face learning is better at convergent study,

such as often associated with directed inquiry and

scientific inquiry. Other authors have noted this gap

in support for electronic converging dialogue with

their own goals to address it (for example, Lid and

Suthers, 2003; Jung et al., 2006).

Therefore, while the previously mentioned tools

are quite good for divergent conversations, MAT is

more useful where convergent conversations are

required; keeping multiple discussions each focussed

on finite issues under analysis. Additionally, the

annotation panels provided in MAT—which can be

employed if and as required for the learning

activity—are designed to provide a range of options.

If used in full, a complete cycle of learning can be

achieved within MAT itself.

To help illustrate the tool further, Figure 1 shows

a MAT test site, where the artefact for analysis is a

neurophysiology procedural video. The video is

playing at the segment marked by the highlighted

(active) red marker in the middle of the video

timeline. The colour of this marker under analysis

indicates the ‘Electrode Placement’ category

(Marker Types list at top right), and the marker has

been individually labelled as ‘Back of head’ for ease

of locating this marker later (framed in marker list

on lower right, and in annotation panel). The

annotation panel named ‘Notes’ has been expanded

to allow the text entry aligned to that piece of

marked video to be read. The rest of the panels are

closed, but could be opened and read by clicking on

their respective arrowheads.

Figure 1: MAT test site: viewing the middle red marker on

a neurophysiology video (yellow framing added).

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

456

3 RESEARCH PROJECT

AND METHODOLOGY

Following indicators of effectiveness of MAT in a

preceding pilot study (that is, integration of MAT in

undergraduate Physical Education; see Colasante,

2011), funding was gained to test this new

educational technology in a range of tertiary

education cases. An internal institutional learning

and teaching grant scheme funded the project. The

study involved using MAT for professional learning

based curriculum that focused on work integrated

learning activities in a range of courses (subjects).

The participant cases were classes of students and

their teaching staff from across disciplines and

sectors. Multiple cases (9) were involved from:

chiropractic, medical radiation, and education (2)

(undergraduate); law (postgraduate); property

services (3) and audio-visual technology

(vocational).

Initial findings from the four undergraduate cases

will be referred to in this paper. While all the cases

across the study harbour unique and varied

characteristics, the four undergraduate cases hold

some base similarities involving the traditional

teaching format for delivery. They were each on-

campus/face-to-face, undergraduate courses

(subjects) as part of a full-time learning program,

run on a traditional weekday lecture/tutorial/

classroom delivery over a semester.

3.1 Undergraduate Cases

The four undergraduate cases and their various

learning purposes for MAT are provided below.

Education-literacy:

Year 3, Semester 1, Primary Education multi-

literacy class;

Learning objective: Develop understanding and

skills in using new media to critique writing

and illustration;

Use of video in MAT: students film and upload

to MAT a draft storyboard of a children's book

that was self-created to give and receive peer

feedback as part of the learning process.

Education-visual arts:

Year 2, Semester 1, Primary Education visual

arts class;

Learning objective: Explore visual arts

teaching, including evaluating own processes

and others;

Use of video in MAT: students create videos to

upload to MAT to (a) document and record

their artistic processes and final art works

during the semester; (b) record and

discuss/reflect on experiences of gallery art

spaces and art education practice in school

settings.

Chiropractic:

Year 2, Semester 2, Chiropractic clinical

assessment class;

Learning objective: Explore the various aspects

of clinical encounters in the chiropractic field

and engage clinical thinking;

Use of video in MAT: students use

professionally prepared video of a clinical

scenario in two parts, uploaded by the teacher

to MAT, to: 1(a) align patient’s history to key

categories; 1(b) discuss/reflect to short-list

diagnoses; 2(a) align patient’s examination to

short-listed diagnoses; 2(b) discuss/reflect to

determine diagnosis.

Medical radiations:

Year 1, Semester 2, Medical Radiations

radiographic imaging class;

Learning objective: Develop image evaluation

skills;

Use of video in MAT: students use a

professionally prepared series of videos of

expert critiques of x-ray quality, simulating

experiences of eventual clinical practice,

uploaded by the teacher to MAT, to identify

and discuss criteria for industry acceptability

of: (a) several upper limb x-ray critiques; (b)

several lower limb x-ray critiques.

3.2 Research Methodology

Multiple-case study methodology was used in this

research project, which sought to understand

whether MAT could improve engagement and

learning experiences for students across different

study disciplines. Students and teachers who used

MAT in 2011 for workplace preparation themes were

invited to participate in the study. The multiple-case

study methodology follows a single, pilot case study

of MAT integration in 2009 (Colasante, 2011), and

reuses the pilot research design with minimal

adaptation. As the cases were purposively selected—

as in cases where the activity under investigation

was occurring (Silverman 2005)—no deliberate

literal replication was designed into the multiple-

case study. However, it is anticipated there are

sufficient similarities and contrasts across the cases

CANAMEDIAANNOTATIONTOOLENHANCEONLINEENGAGEMENTWITHLEARNING?-AMulti-case

Work-in-progressReport

457

to anticipate some literal and/or theoretical

replication (Yin, 2009) to emerge over the data

analysis processes.

3.3 Data Collection

Mixed method data collection involved student

surveys, individual observation and interview

sessions for students and teachers, plus learning

artefact analysis. For this early ‘work-in-progress’

paper, the data related to the student surveys, teacher

interviews and artefact analysis across the four

undergraduate cases are examined to establish

whether students were engaged in their learning

activities with MAT, and whether factors that might

enhance engagement can be determined.

Students who chose to participate in the study

completed a survey in two parts: a pre- and post-

survey. Each part of the survey comprised both

quantitative (mainly Likert scale styled) and

qualitative (open-ended) questions. The pre-survey

was administered at the beginning of the semester

just before using MAT, and asked for learner profiles

and attitudes for an unfamiliar but expected online

learning tool. The post-survey was administered at

semester end and sought student perspectives on

experiences with MAT in their learning. Each of the

teachers of the classes chose to participate in the

interviews, or ‘interactive process interviews’

(Colasante, 2011), which involved them first

demonstrating and explaining their class use of

MAT, followed by a semi-structured interview. The

interviews, along with learning artefact analysis,

occurred after the academic semesters, when all

participating students had finished their activities in

MAT and all assessment results were finalised.

Table 1: Student participation levels in the study.

Case

Class

size

Pre‐surveys

completed

Post‐surveys

completed

Education

(literacy)

18 15(83%) 12(67%)

Education

(visualarts)

59 18(31%) 13(22%)

Chiropractic 78 39(50%) 37(47%)

Medical

Radiation

57 36(63%) 33(58%)

TOTAL

212 108(51%) 95(45%)

The two education cases, visual arts and literacy,

used MAT in first semester 2011; the two health cases,

chiropractic and medical radiations, second semester.

The classes ranged in size from 18 to 78 and student

survey participation rates ranged from 22 to 83 per

cent. Across the four cohorts, 108 pre-surveys and 95

post-surveys were completed (Table 1).

4 DISCUSSION OF

PRELIMINARY FINDINGS

At this work-in-progress stage, there are mixed

findings emerging related to MAT’s effectiveness in

engaging students across the four undergraduate

cases—which tends to raise questions for further

analysis as the project is completed. However, from

this early analysis point an interesting divergence in

findings can be demonstrated.

4.1 Basic Interaction

On the surface, it is inferred that there was

considerable activity in MAT across the four

undergraduate cases. Artefact analysis of basic

activity (i.e.: active in at least one of the following:

added media, created a marker, communicated in

MAT) illustrates high rates of interaction with MAT

by students of the chiropractic and the two education

cases; while just under half of the students engaged

with MAT for the medical radiations class (Table 2).

Table 2: Basic student activity levels in MAT.

Case

Students

activein

MAT

Markeraverage

(range)/student;

total

Videos

usedin

MAT

Education

(literacy)

17/18=94% 3(0‐17)

58

30

Education

(visualarts)

53/59=90% 4(0‐16)

231

112

Chiropractic

75/78=96% Vid1:15(13‐23)

1161

Vid2:7(2‐17)

512

1

1

Medical

Radiation

28/57=49% 10(0‐58)

276

10

These patterns of interaction are validated by

teachers, but do not tell the full story. On deeper

analysis of the patterns of interactions, it was

realised that education student cohorts had

alternative means for presenting their video

artefacts, rather than using MAT only (due to

technical difficulties for some students).

Consequently, not all students uploaded their videos

in MAT; some submitted their videos by other means

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

458

for proof of storybook creation for literacy, and for

visual arts the teacher expected one video upload per

week over a 10 week period while the average

upload was two videos per student. In education-

literacy only seven were annotated (some quite

extensively); education-visual arts videos were

annotated sporadically. The high rates of

chiropractic student interaction with MAT are

associated with learning that formed a required part

of the learning program and assessment.

Alternatively, the significantly lower interaction

with MAT use by the medical radiations and

education students reveals that the MAT learning

activities were encouraged but voluntary.

Additionally, looking at the education cases, the

students were in the main active video up-loaders in

MAT. The education cohorts each came close to

averaging two student-produced videos per

student—although the range was 0-9 per student—

compared to the health cohorts where the teachers

(or their support personnel) uploaded professionally

produced videos. These results indicate that not all

education students were highly active in the MAT

space as was intended in the curriculum design.

Self-reporting by survey participants supports

that time was spent with MAT. Two post-survey

questions on this reveal that students tended to use

MAT in either regular patterns (weekly or twice

weekly), or irregularly in intense bursts around times

of video availability in MAT or just before

assessment due dates. A minority used MAT rarely

or not at all in each of the cohorts apart from

chiropractic (23% for medical radiations, 17% for

education-literacy, 8% for education-visual arts).

The chiropractic students reported as the most

frequent users of MAT. A question on time spent on

average in any one episode reveals that 15 to 30

minutes is the most common time commitment using

MAT across the four cohorts, with a spread of less

than 15 minutes through to approximately two

hours. It is notable that three out of the four cases

(all but education-literacy) had a small percentage of

students spending one-and-a-half hours or more in

single episodes using MAT.

While time engaged with MAT is a useful

indicator—indeed time on task is one of the time

honoured ‘seven principles of good practice in

undergraduate education’ (Chikering and Gamson,

1987; Chickering and Ehrmann, 1996)—these

figures don’t tell us whether the time was devoted to

quality learning or time spent navigating a new tool.

4.2 Deeper Engagement

While student interaction with the tool is evident

from the data, learner engagement on a deeper level

appears more sporadic across the four cases. For

example, when asked questions on learning

effectiveness and preference of using MAT, the

survey responses vacillated wildly between the

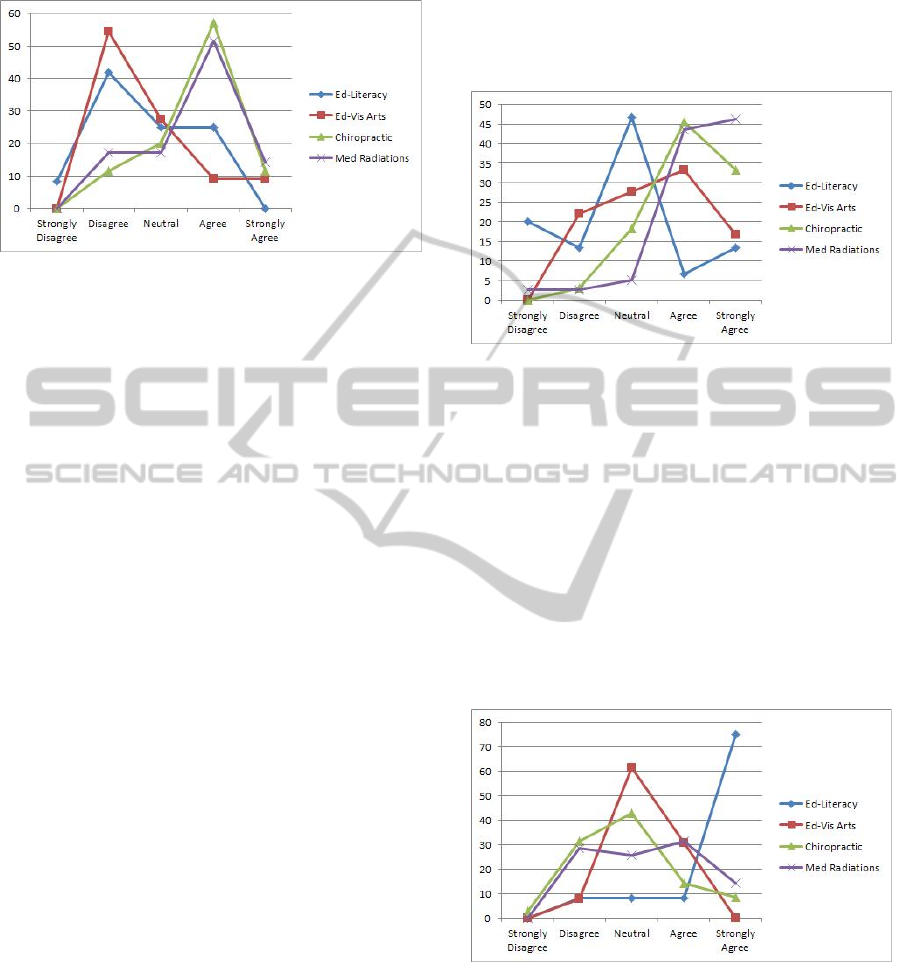

cases. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate this picture, and by

extension raise further questions about the factors of

variance (Section 4.3).

The most striking variations are the peaks

between education-visual arts and chiropractic

(Figure 2), where two-thirds of the former disagree

(67%) that MAT allowed them to be challenged in an

interesting way, while a similar number in the latter

agrees (69%). Even so, each cohort has at least some

polar opposite opinion within their own ranks; with

one-quarter education-visual arts respondents

agreeing they were challenged, and one-eighth of

chiropractic respondents stating they were not.

Relative to this, the education-literacy and

medical radiations cohorts were more mixed within

their own cases on this question. In the education-

literacy case, two-fifths (42%) were neutral

compared to those that agreed that they were

challenged in an interesting way, while in medical

radiation, just under one-quarter (23%) disagreed

when over half agreed (57%).

Figure 2: MAT allowed me to be challenged in an

interesting way (%).

To the question of MAT allowing them to build

or construct meaning from their learning

experiences, Figure 3 paints a similar picture of

opposite peaks between the education-visual arts and

chiropractic cohorts, although a few more neutral

responses soften the decisiveness a little. Medical

radiations almost mirrors the response patterns to the

previous question, albeit slightly stronger with two-

thirds (67%) agreeing. Education-literacy sees the

most change between this and the previous question,

with half disagreeing on this question and one-

CANAMEDIAANNOTATIONTOOLENHANCEONLINEENGAGEMENTWITHLEARNING?-AMulti-case

Work-in-progressReport

459

quarter agreeing.

Figure 3: MAT allowed me to build or construct meaning

from my learning experiences (%).

4.3 Case Contexts

The question of case contexts and uses of MAT was

raised in the previous discussion in light of the mix

of polar and indecisive case representation of

learning experiences. In response to this, the

following case context data is presented and

discussed to illustrate some of the characteristics of

the four undergraduate cohorts, including:

How MAT functionality was used across the

cases;

Student perspectives on:

o preferences of online learning

compared to face-to-face;

o barriers to learning using MAT.

These follow in the order of: student attitudes to

online learning; case uses of MAT as related to

Kirkwood’s (2009) functions of educational

technology; ideas emerging on engagement; and

then perceived learning blockages while using MAT.

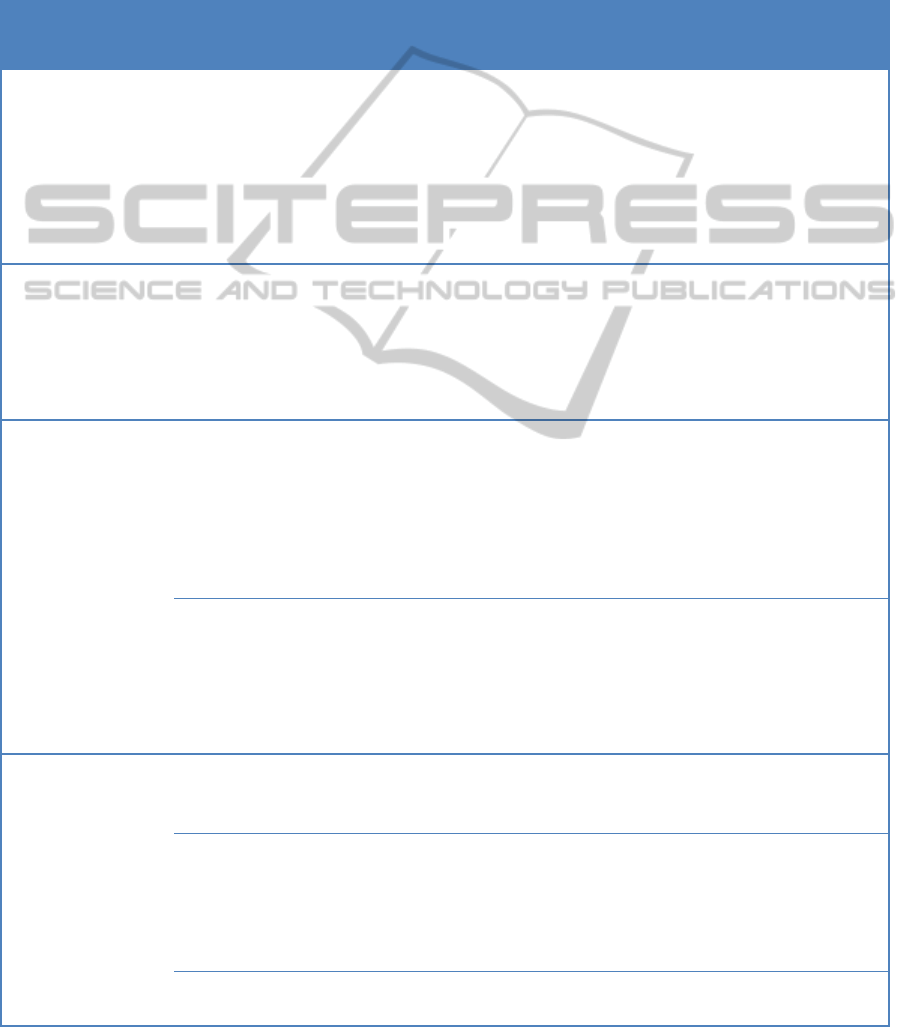

4.3.1 Student Attitudes to Online Learning

As an indication of preference for online compared

to face-to-face learning, figures 4 and 5 show

student preferences pre- and post-MAT use. Figure 4

offers something interesting; the learner cohorts who

responded the greatest disagreement to the questions

on learning satisfaction with MAT, i.e.: the two

education cohorts, had indicated in the pre-survey

less preference for using an online tool to help them

achieve learning outcomes aligned to MAT use.

However, this is relative to the other cases and

not a definitive factor, as still half of the education-

visual arts students surveyed agreed overall (50%),

while around one-fifth (22%) disagreed (Figure 4).

For education-literacy, outside a large neutral

response only one-fifth agreed to preference for an

online tool (20%) while one-third disagreed

(33.3%). Compare this attitude to pre-MAT

agreement from four-fifths of the chiropractic

respondents (79%) and most of the medical radiation

respondents (90%), with almost negligible

disagreement from these two cohorts.

Figure 4: I would like to use an online tool to help me to

(achieve the various intended learning outcomes) (%).

The education-literacy cohort remained

consistent with their pre-survey attitudes after using

MAT. Figure 5 illustrates the responses to the post-

survey question on whether they would have

preferred face-to-face discussions for their learning

instead of using MAT. From the education-literacy

cohort there is striking agreement to face-to-face

preference over MAT. There is also striking non-

decision on this question from the education-visual

arts cohort, and a mixed response from both

chiropractic and medical radiation cohorts including

substantial non-decision.

Figure 5: I would have preferred to have face-to-face

discussions about the learning instead of using MAT (%).

4.3.2 MAT Integration: Comparisons and

Contrasts across Cases

The four cohorts, apart from using MAT over the

typical undergraduate semester, had quite different

purposes for MAT integration (Section 3.1). Their

learning activities directly involving MAT varied

including using different features of the tool. Using

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

460

Kirkwood’s (2009, p.108) functions of educational

technology as categories (quoted in italics below), a

snap shot of MAT integrations harnessed from

teacher interviews and supported by artefact analysis

data, is tabled below.

Kirkwood (2009) noted the next frontier for ICT

in higher education was to extend or transform,

rather that replicate or add to current teaching

methods, enabling “learning activities or situations

that would otherwise be extremely difficult to

achieve and to facilitate qualitative improvements in

learning outcomes” (p.108). At this preliminary

stage of data analysis it is difficult to determine

whether student learning has extended to levels

Table 3: Case uses of MAT (from teacher interview data) aligned to Kirkwood (2009) functions of ICT in higher education.

ICTFunctions

(Kirkwood,2009,

p.108)

Education‐literacy Education‐visualarts Chiropractic Medicalradiations

presentation–making

…resources([e.g.:]…

movingimages,etc.)

availableforstudents

toreferto,eitherat

predeterminedtimes

or‘ondemand’

Studentscreatedown

videos,includinga

supervisedsamplevideo

touploadasan

example.

Studentscreatedown

videos;initiallythe

teacheruploadedtwo

examplevideosto

demonstratebothgood

andpoorquality.

Clinicalepisode

(enactedbychiropractic

expertandstaff)

presentedinstagesin

twoseparatevideos

releasedprogressively

overthesemester.

Expertmodelling

(sloweddown&

spokenaloudbya

radiographer)ofx‐ray

critiqueprocess,10

scenariosin10videos,

releasedintwo

batchesover

the

semester.

interaction–enabling

learnerstoactively

engagewith

resources,to

manipulateor

interrogate

informationordata

Uploadownvideo/s;

Analyseapeer’svideo

content&selectareas

to,name,categorise&

enterpeerfeedback.

Uploadownvideos;

Analyseownvideo

content;tagvideoswith

keywords;optional:

selectareastoname,

categoriseandenter

notes.

Analysepresented

videocontent;select

areastoname,

categorise&enter

notes;collaboratethen

furtherannotate

videos.

Analysepresented

videocontent;

Selectareastoname,

&enternotes.

dialogue–facilitating

communication

betweenteachersand

learnersorbetween

peersfordiscussion,

cooperation,

collaboration,andso

on

Studentsinonegroup

couldviewwholeclass’

videos;pairswereto

givepeerfeedbackto

eachother’svideos

usingthemarkersand

‘Notes’(notalldid)

Studentsintwoclass

groupscould

viewtheir

group’svideos,tags&

anyannotations;

commentsweremore

oftenforselfthanfor

others.

Individualanalysisthen

smallgroupcomparison

&collaborationto

achievesetgoals,using

annotation&

communicationareasin

MAT&/ormethods

Studentsinsmall

groupscouldview

groupmembers’video

annotations(didnot

tendtoleave

commentsforeach

otherbeyondown

studytypeentries).

Teacherfeedbackgiven

viathegeneral

communicationarea,

notlinkedtospecific

videosegmentsbutto

theirindividualvideo/s

Teacherfeedbackwas

notgivenwithinMAT

Teacherfeedbackgiven

viathe‘Teacher

Feedback’annotation

panelsanchoredtoonly

specificallytargeted

markedvideosegments

Teacherfeedback

givenviathe‘Teacher

Feedback’annotation

panelonallmarkers

studentsannotated/

showedengagement/

madeeffort

generativeactivity–

enablinglearnersto

record,create,

assemble,storeand

retrieveitems…in

responsetolearning

activitiesor

assignmentsandto

evidencetheir

experiencesand

capabilities

Studentscreatedadraft

storyboard,videoedthis

work&uploadedto

MAT

Studentscreatedvideos

oftheirworkasartists&

ofart

spaces&

uploadedtoMAT

Studentsdidnotcreate

ownvideos

Studentsdidnot

createownvideos

Severalstudentsonly

createdmultiple

markersacrossthe

timelineofapeer’s

video.

Createdgeneraltag

namesfortheirvideos;

someleftnotesin

markersorgeneral

commentsarea.

Groupsgenerated

markercategoriesfrom

1

st

videotoanalyse2

nd

video;allstudents

createdmultiple

markersacrossboth

videos

Somestudents

createdmultiple

markersacrossthe

timelineofsomeof

thevideos

Notassessed Notassessed

ActivitiesinMATwere

assessed

MATactivitiescould

aidexampreparation

CANAMEDIAANNOTATIONTOOLENHANCEONLINEENGAGEMENTWITHLEARNING?-AMulti-case

Work-in-progressReport

461

of transformation with MAT. Yet in the health cases,

having access to industry representatives via video

has offered repeat access to expert perspectives, and

in chiropractic, this has enabled access to case

demonstrations earlier in the learning program than

previously. This will be an area for further

investigation.

4.3.3 Emerging Ideas on Engagement

Kirkwood argues on two fundamental elements for

effective use of educational technology, “(1)

variations in users’ conception of teaching and

learning, and (2) the primacy of assessment

requirements” (2009, p.110). The preceding

discussion has included student online/face-to-face

preferences and details (compares and contrasts) the

varying functional foci across the cases giving us a

glimpse into the teacher role, including whether

assessment was a factor of MAT activities (Section

4.3.1 and 4.3.2).

As early adopters of a new tool, the team of

teachers volunteered for the project without

established and proven ways of using MAT (apart

from the pilot study), knowing that there were no

guides as such, but rather models; while teaching

and student guides would be end products of the

project. Professional development and support

related primarily to technological use due to the real

need to learn how to use the new technology.

However, from the discussion in the paper, the

following ideas emerge as practices that assisted

students to engage with MAT.

Higher satisfaction responses by students were

presented in MAT cases that had some or all of:

1. teacher presentation and upload of videos

in MAT (compared to student generation

and upload of videos)

2. teacher feedback

3. learner-learner interaction to achieve

meaningful goals

4. formal assessment requirement.

The last three points would hardly draw

argument, as they are part of well-established

principles for student centred or active learning (e.g.:

Biggs and Tang 2007; Boud et al 2001; Boud and

Falchikov, 2007; Weimer, 2002; Herrington et al,

2010; Garrison and Vaughan 2008). However, the

first point needs to be further explored, as it does not

sit easily with the widely accepted notion of active

learning as more beneficial than passive learning.

Students generating media, compared to being

presented with media, is certainly more active on a

passive to active continuum. Yet the students

reported less willingness to engage with MAT if they

were actively creating and uploading their own

video media (i.e. the education cases).

The current digital climate sees a ‘new culture of

learning’ that enables students to go beyond

‘knowing, making and playing’ in a traditional

sense; students can make, shape and manipulate

media as an integral part of their learning processes

(Thomas and Brown, 2011). So, in this climate, what

does the first point allude to? Could it be that the

education students are not typical digital natives who

are expected to be familiar with and stimulated by

ICT? Do they have a higher percentage of students

with a ‘passive conception’ of learning (Saljo, 1979,

in Kirkwood, 2009), and that while not happy with

their experiences with MAT, may have successfully

developed and extended (Perry, 1970, in Kirkwood,

2009) in the act of finding themselves thrust in a

creative role? These are questions raised but as yet

unanswered.

4.3.4 Barriers to Engagement

Although Kirkwood (2009) states effectiveness is

less about the tool and more about how it is used,

MAT is new so technological barriers also need to be

considered. In aiming to isolate any blockages that

may have affected the students’ learning with MAT,

one of the qualitative questions in the post-survey

asked an open-ended question regarding if there was

anything about MAT that blocked them moving

forward in their learning. Out of the responses given

(not all chose to answer this question) themes

emerged that fell under either umbrella of technical

or pedagogical issues (Table 4 and 5).

Student generation and upload of videos should

have provided active, deeper learning experiences.

Perhaps the technological difficulties noted by the

learners of the education cohorts, mixed with their

self-reported preference for face-to-face learning

over online learning (Section 4.3.1) affected their

engagement. However, Kirkwood's (2009) argues

that technology limitations is not the greatest barrier

to engaging effectively with online learning, but

rather it is how it is used, integrated and aligned with

expectations between students and teachers.

This argument provides the opportunity to revisit

Barkley’s (2010) theorising on the complexity of

student engagement for learning where both

motivation and active learning synergistically

interact. From the preliminary data analysis it seems

that there are two dominant project foci to i) provide

technical support for the project’s teachers and

students; and ii) develop and share learning and

teaching strategies that focus on active learning

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

462

within the project teaching teams.

Table 4: Things about MAT that blocked students moving

forward in their learning: (a) Technical Difficulties.

Case TechnicalDifficulties

Education

(literacy)

Mostcommonresponsewasdifficulty

uploadingvideos,e.g.:

“Ihadproblemstoupload[sic]mydraft

videowithinuniorathome”;

“Take[s]longtimetouploadfiles.”

Education

(visualarts)

Mostcommonresponsewasdifficulty

uploadingvideos,e.g.:

“Itwashardtouploadvideos–ittookages

toupload(allnight)”;

“ifthevideodidn’tupload,youwere

unabletofollowthroughwithclasstasks”.

Chiropractic

Aminoritynotedaccess/usageissues,e.g.:

“thesitewasoccasionallyverydifficultto

use”;

“notthesmoothestwebsite,butonceyou

knewhoweverythingworked,itwas

alright,howeverslow”.

Medical

Radiation

Aminoritynotedgeneraltechissues,e.g.:

“wascomplicatedandconfusingtouse”;

“userinterfacewasnotveryuse[sic]

friendly”.

Table 5: Things about MAT that blocked students moving

forward in their learning: (b) Pedagogical Issues.

Case PedagogicalIssues

Education

(literacy)

Oneonlynotedparticipationlevels,i.e.:

“Other students not spending much time

on MAT. It should be graded to

compensate for ppl [people] spending lots

oftimeonit”

Education

(visualarts)

Some did not see the relevance of MAT,

e.g.:

“Therewasemphasis on puttingthings up

butfeltlikeitwaspointless.”;

“didn'treallyseethepurposeofit.”

Chiropractic

Aminority criticisedthegroup formations

andrelatedparticipation,e.g.:

“not being able to choose our own group

members”;

“notallgroupmembersparticipatedwhich

made it hardto come up with decisions as

agroup”

Medical

Radiation

Aminoritywouldhavepreferredtodo

theirownimagecritiquinginMAT(rather

thanwatchanexpert),e.g.:

“weweren'tabletoattemptcritiquingthe

imagesourselvesas[theexpert]didit

already”.

For some students (almost half the students),

MAT provides positive influences as they engage in

their learning actively through positive challenge

and meaning making (refer to Figures 2 & 3). Yet

there seems to be another factor that contests a

deeper engagement for learning with MAT. While

the design and use of MAT fosters active learning,

the other element of student engagement -

motivation - seems to have become lost in

implementation in some of the cases. As Barkley

(2010) argues, motivation incorporates a mix of self-

perception, insights, dispositions, skills, expectancy

and value that will influence the student’s will to

learn.

With this insight in mind, returning to Table 4,

there is a sense that while students were actively

learning with MAT, their sense of purpose or value

of using MAT for their learning is diminished. The

students’ comments such as the need ‘to

compensate’ for time spent on MAT in assessment;

the feeling that ‘it was pointless’; they wanted

choice in their peer partners; and lack of opportunity

to create their own videos – are at the heart of the

construct of motivation for learning. These students

are demonstrating a lack of motivation in the use of

MAT as they are searching for a deeper engagement

with MAT for their learning. If “motivation is the

portal to engagement”, as Barkley (2010, p. 15)

contends, then there is a need for further thinking

about how MAT might be used to increase

motivation for students in their learning. As a tool

that is directly reflective of work integrated learning,

MAT has the potential to engage students in their

professional learning. Further analysis of the

project’s data hopes to shed light on how the

authenticity of MAT learning activities might be

used to help bolster the motivation element of

student engagement.

5 NEXT STEPS

Project completion includes finalising the data

analysis and preparation of report. Additionally, by

evaluating MAT’s effectiveness in the varied

contexts, models of work-relevant learning are

emerging that optimise virtual, authentic learner

engagement. MAT guideline booklets for use,

student and teacher versions, are currently under

development as informed by the project experiences.

These models of use and the development of

supporting guidelines will then be available to

support further use of MAT and—as new products—

be open to further (post-project) evaluation.

CANAMEDIAANNOTATIONTOOLENHANCEONLINEENGAGEMENTWITHLEARNING?-AMulti-case

Work-in-progressReport

463

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors—and project facilitators—would like to

acknowledge the rest of the project team for their

eagerness to be the early adopters, and in most cases

active project researchers, of this new educational

technology. Many thanks to Amanda Kimpton,

Jenny Hallam, Narelle Lemon, Wendy Warren,

Giovanni Mandarano, Kathy Douglas, Michele

Ruyters, Christine Peacock, Michael Leedham, and

Rebekha Naim; all were key to the project and

comprised a delightful and productive team.

This project received funding from the RMIT

University Learning and Teaching Investment Fund

(LTIF) 2011.

REFERENCES

Andrews, R., Haythornthwaite, C. (Eds), 2007. The SAGE

Handbook of E-learning Research. Los Angeles:

SAGE Publications.

Barkley, E. F., 2010. Student Engagement Techniques: A

Handbook for College Faculty. Jossey-Bass. San

Francisco.

Biggs, J., Tang, C., 2007. Teaching for quality learning at

university: What the student does. (3

rd

ed.)

Maidenhead & New York: Society for Research into

Higher Education & Open University Press.

Boud, D., Cohen, R., Sampson, J. (Eds.), 2001. Peer

Learning in Higher Education: learning from & with

each other. London: Kogan Page.

Boud, D., Falchikov, N. (Eds.), 2007. Rethinking

Assessment in Higher Education: Learning for the

longer term. London and New York: Routledge.

Chickering, A. W., Ehrmann, S. C., 1996. Implementing

the seven principles: Technology as lever. American

Association for Higher Education Bulletin, 49(2), 3-6.

Retrieved online 9 January 2012 from

http://www.aahea.org/bulletins/articles/sevenprinciples

.htm.

Chickering, A. W., Gamson, Z. F., 1987. Seven principles

for good practice in undergraduate education.

American Association for Higher Education Bulletin,

39(7), 3-7. Retrieved online 9 January 2012, via

http://www.aahea.org/bulletins/articles/sevenprinciples

1987.htm.

Colasante, M., 2011. Using video annotation to reflect on

and evaluate physical education pre-service teaching

practice. Australasian Journal of Educational

Technology, 27(1), 66-88. Via http://www.ascilite.org.

au/ajet/ajet27/colasante.html

Garrison, D. R., Vaughan, N. D., 2008. Blended Learning

in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and

Guidelines. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. C., Oliver, R., 2010. A guide to

authentic e-learning. New York and London:

Routledge.

Kirkwood, A., 2009. E‐learning: you don't always get

what you hope for. Technology, Pedagogy and

Education, 18(2), 107-121. Via http://www.

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14759390902992576

Jung, B., Yoon, I., Lim, H., Ramirez-Weber, F., Petkovic,

D., 2006. Annotizer: User-friendly WWW annotation

system for collaboration in research and education

environments. Paper presented at the IASTED Web

Technologies, Applications, and Services, pp.113-118.

Lai, K. W., 2011. Digital technology and the culture of

teaching and learning in higher education. In Hong, K.

S., and Lai, K. W. (Eds), ICT for accessible, effective

and efficient higher education: Experiences of

Southeast Asia. Australasian Journal of Educational

Technology, 27 (Special issue, 8), 1263-1275.

http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet27/lai.html

Lid, V., Suthers, D., 2003. Supporting online learning with

an artifact-centered cross-threaded discussion tool. In

Chee, Y. S., Law, N., Suthers, D., and Lee, K. (Eds.),

proceedings of the International Conference on

Computers in Education 2003, December 2-5, Hong

Kong

Silverman, D., 2005. Doing qualitative research. (2nd

ed.). London: SAGE Publications

Swan, K., 2004. Relationships between interactions and

learning in online environments. Learning, 3, p.A

collection of research findings and their implic. ©

Sloan-C. Retrieved online 10 January 2012, via

http://www.sloan-

c.org/publications/books/pdf/interactions.pdf.

Thomas, D., Brown, J. S., 2011. A new culture of

learning: Cultivating a culture of imagination in a

world of constant change. Seattle, WA: CreateSpace

Publishing.

Weimer, M., 2002. Learner-Centered Teaching: Five key

changes to practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Yin, R. K., 2009. Case study research: design and

methods, 4

th

ed. Los Angeles, Calif.: Sage Publications

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

464