Evaluation of Maturity Models for Business Process Management

Maturity Models for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

Johannes Britsch

1

, Rebecca Bulander

2

and Frank Morelli

2

1

University of Mannheim, Institute for SME Research, L9, 1-2, 68161 Mannheim, Germany

2

Pforzheim University of Applied Sciences, Tiefenbronner str. 65, 75175 Pforzheim, Germany

Keywords: Business Process Management, Maturity Model, Evaluation, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises,

Anything Relationship Management.

Abstract: This paper contains an appraisal of selected maturity models for BPM. Business process maturity models in

general offer precise process definitions, repeatable process operations, the integration and interaction with

linked processes, as well as the measurability and controlling of the process flows. Maturity models provide

small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with clear structures for organizational changes. The intention

of the analysis is to support SMEs by choosing an appropriate framework that helps to design “to-be”

business processes based on a continuous and comprehensive assessment concept. However, due to their

size and limited resources, SMEs also have special requirements regarding maturity models. The paper

describes the evaluation results of well-known maturity models for SMEs and the advantages and dis-

advantages of the models relating to a concrete scenario in the area of Anything Relationship Management.

1 INTRODUCTION

For effective and efficient management, it is essen-

tial to gain transparency about existing processes in

order to avoid negative developments and to explore

potentials for optimization. Today, small and medi-

um-sized enterprises (SMEs) can find a wide range

of models to assess and improve business processes.

The open question is: which ones suit them best?

Business processes are a powerful means to put

enterprise strategies into practice. In contradiction to

a widespread view, especially among SMEs, busi-

ness process management (BPM) does not only deal

with rigid process standardization, but pursues the

goal of improving agility, innovation, and speciali-

zation. The structured BPM approach comprises

methods, policies, metrics, management practices,

and software tools to manage and optimize activities

of a firm. Important hereby is that BPM should be

applied continuously – instead of the typical mis-

conception that BPM stands for a one-time project.

Using BPM continuously as a vehicle, there are

many ways to improve processes. However, before

deciding arbitrarily to optimize an existing process,

it is necessary to gain an integral perspective about

the “as-is” state. For a company this means having

defined processes, performance indicators, and the

willingness for continuous improvement. Surpris-

ingly, although BPM is part of a tradition that is now

several decades old (Harmon, 2010, p. 37), even in

large-scale enterprises a systematic and ongoing

assessment of BPM activities cannot be found very

often (Knuppertz et al., 2010, p. 10).

This paper contains an appraisal of selected

maturity models for BPM. The intention of the ana-

lysis is to support SMEs by choosing an appropriate

framework that helps to design “to-be” business pro-

cesses based on a continuous and comprehensive

assessment concept. Business process maturity

models in general offer precise process definitions,

repeatable process operations, the integration and

interaction with linked processes, as well as the

measurability and controlling of the process flows

(McCormack and Lockamy, 2004, p. 2).

Maturity models thus provide SMEs with clear

structures for organizational changes. However, due

to their size and limited resources, SMEs also have

special requirements regarding maturity models.

Hence, relevant evaluation criteria and to which ex-

tent different maturity models fulfill those criteria

will be thoroughly discussed. Using the hypothetical

scenario of an SME introducing the new relationship

management platform concept “Anything Relation-

ship Management” (xRM) (Britsch and Kölmel,

180

Britsch J., Bulander R. and Morelli F..

Evaluation of Maturity Models for Business Process Management - Maturity Models for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises.

DOI: 10.5220/0004074701800186

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Communication Networking, e-Business and Optical Communication Systems (ICE-B-2012),

pages 180-186

ISBN: 978-989-8565-23-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2011, p. 3), the paper describes the advantages and

disadvantages of the respective maturity models.

2 THE SPECTRUM OF CHOICES

SMEs that measure operational performance only by

financial key figures often recognize too late when

changes occur (Hammer, 2010, p. 7). Key perfor-

mance indicators, derived from business processes

that link cross-functional or inter-company value-

based activities, reflect alteration by contrast. BPM

proves to be a consistent system of leadership, or-

ganization, and controlling, driven by customer-

needs to fulfill the strategic and operative goals of a

company (Schmelzer and Sesselmann, 2010, p. 316

f.).

Supported by IT-based approaches, BPM offers

the opportunity to gain process performance infor-

mation in real-time. For predictions, incoming infor-

mation can be combined with further data to per-

ceive interdependencies as well as potential threats

and opportunities. As a consequence, BPM results in

a management practice which encompasses all activ-

ities of identification, definition, diagnosis, design,

execution, monitoring, and measurement.

Maturity models reflect the ability of an organi-

zation for sustainable and forceful action in the

related domain. The maturity model concept is based

on the tradition of other management approaches to

measure the quality of an organizational subject

(product or service). Within BPM, maturity model-

based assessments can serve as a way to focus on

certain process management improvement efforts.

The framework of the model comprises struc-

tured elements that shape the comprehensive per-

spective of BPM. Based on transparent, objectified

criteria, a maturity profile of the “as-is” state of a

firm is defined. Quantitative as well as qualitative

business process characteristics are covered. This

insight is expected to lead to decisions that improve

the current situation in the sense of designing “to-

be” business processes.

In science as well as in practice, an impressive

number of BPM maturity models have emerged.

This variety offers choices for SMEs, but at the

same time it creates a challenge to select the most

suitable model. The set can be sorted into two types

of maturity models (see Zwicker et al., p. 382 and

the quoted sources): models with a holistic orienta-

tion for BPM and models focusing on facets of BPM

(e.g. Rosemann et al., 2006).

Typically, BPM maturity models are designed

from a comprehensive perspective whereas domain

specifics or particular application contexts are hardly

considered; recommendations for BPM improve-

ment are scarce (Zwicker et al., p. 383). Many matu-

rity models differ between several levels which are

based on each other. Thus, a continuous maturity

model application increases the probability to use

BPM successfully as a core management approach.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

To evaluate the existing maturity models for BPM

we at first conducted an extensive literature review.

Therefore, we reviewed a total of over 70 scientific

papers, 20 books, and 30 other publications, also out

of professional practice.

For the selection of the maturity models we

defined the following criteria: the model has to be

related to BPM; the description of the model has to

be open to the public, and it must be widely spread.

The latter of the afore-mentioned criteria was

validated by several research studies about the

dissemination of maturity models in business, e.g.

Knuppertz et al., 2010.

In a next step the selected maturity models were

described (see chapter 4). To evaluate the selected

maturity models evaluation criteria were defined.

These criteria were deduced by the needs of SMEs

and also by former studies e.g. Dombrowski, et al.,

2011 and Schmelzer et al., 2010. In order to quantify

the peculiarity of each criterion, we used the Likert

scale categorization. Each criterion was rated on a

scale from one to five (see also chapter 5) according

to discussions among the authors and their resulting

joint judgments based on the literature review.

4 AN OVERVIEW OF SELECTED

MATURITY MODELS

Over the years the Capability Maturity Model Inte-

gration (CMMI; Ahern et al., 2004; Chrissis et al.,

2006; Hofmann et al., 2007) established its status as

the de facto standard for business process organi-

zation. The model is applied in different industries

and shows a high degree of popularity in the US, In-

dia, China, and in big German companies like Bosch

or Siemens. Due to the high acceptance level, many

other business maturity models refer to CMMI.

The CMMI model distinguishes between a con-

tinuous and a staged representation: The continuous

representation allows focusing on certain process

Evaluation of Maturity Models for Business Process Management - Maturity Models for Small and Medium-sized

Enterprises

%p

areas as summary components which are important

depending on the business objectives. As a result, an

organization can be awarded a capability level

achievement and/or target profile. There are six ca-

pability levels, numbered 0 through 5.

More typical for the CMMI approach is the

staged representation to assess the overall maturity

across an organization. As a scale the assessment

uses a maturity level rating (1 - 5). A certain level is

reached when the requirements of this level as well

as all the ones of the lower levels are met. It is deter-

mined by using an appraisal, based on the Standard

CMMI Appraisal Method for Process Improvement

(SCAMPI). Within an appraisal, strengths and weak-

nesses of the processes are identified, comparisons

to CMMI best practices are performed, and the

transfer of requirements is evaluated. The idea is to

identify areas where improvement can be made, and

to provide an implementation roadmap.

CMMI can be described as a map to systemati-

cally design operating principles and methods within

an organization. Good practices may be used for

analysis and improvement of the “as-is” situation.

However, the CMMI model focuses more on what

processes should be implemented, and less on how

they can be implemented.

The original development of EDEN took place

between 2006 and 2008 and was based on individual

models from European companies from different

industries. It was performed by a practitioner-

dominated task force whose goal is the ongoing

advancement and improvement of the model.

The industry independent EDEN model distin-

guishes an organizational layer and a process layer.

The focus on the organizational layer is to identify

how process management has been put into practice.

The purpose of the second layer is to assess the dif-

ferences in maturity for single processes. The meas-

urement is based on nine dimensions (e.g. strategy,

organization, IT) and consists of 170 different crite-

ria. However, compared to CMMI, it is less detailed

(Schnägelberger, 2009, p. 12). Complementary mod-

ules can be added for taking industry-specific and

further aspects (e.g. SOX- or FDA-requirements)

into account. It is possible to combine EDEN with

CMMI and other business process maturity models.

Besides the assessment of the “as-is” situation, a

mid-term and a long-term “to-be” value are recorded

for each criterion from the perspective of the com-

pany. The measurement of the criteria in detail is

performed with a questionnaire using a scale of 10

items. The transformation of the result leads to a

grading within 6 maturity levels for each dimension.

EDEN furthermore intends to determine fitting

strategies for action. Therefore, a categorization into

two dimensions, progress (e.g. “new” vs. “imple-

mented”) and proceeding (bottom-up vs. top-down),

takes place. Together they encompass a positioning

matrix containing four areas (marsh, field, meadow,

and garden). The guidance to be created then shows

the path from the starting point (typically marsh) to

the garden of EDEN. However, the model does not

comprise concrete procedures for implementation.

EDEN offers a certificate for the application of

the standard modules. Besides the large catalogue of

criteria, EDEN has a simplified schema for self-

assessment. Here only the “as-is” status is recorded

and the range of possible answers is reduced.

The acronym SPICE stands for “Software Pro-

cess Improvement and Capability Determination”

and represents the ISO/IEC 15504 standard for

assessing business processes with a focus on soft-

ware development. The currently valid international

standard comprises five parts: part 2 has a normative

character; the other ones can be characterized as

appendices and provide examples and explanations.

SPICE focuses on the improvement of processes

within an organization as well as the capability of

suppliers for process interaction. Neither mandatory

processes nor concrete assessment criteria are de-

fined. Yet, Part 5 of the international standard shows

concrete process reference models (PRMs) and pro-

cess assessment models (PAMs).In the meantime,

industry-specific SPICE models also have emerged

(e.g. Automotive SPICE for the automotive industry,

MediSPICE for medical engineering).

The international standard comprises primary re-

quirements for PRMs on how to describe processes.

Process attributes (e.g. process performance, defini-

tion, and measurement) have to be characterized by

correlated primary management activities and serve

for the assessment of each process. PAMs are speci-

fied with criteria for methodological evaluation.

The capability dimension has six levels that

reflect performance competence. Process grading is

based on a combination of the reference model and

the assessment model: the process dimension of the

reference model is used for identification, selection,

and categorization of the concrete business process-

es to be assessed. In total nine process attributes are

assigned to the capability levels ensuring that the

results are developed systematically and with a high

quality. The capability dimension of the assessment

model is used to determine the efficiency of the cho-

sen processes. In contrast to CMMI it is not easy to

fulfill the requirements for the first capability level.

Basis for the evaluation is not only the existence

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

%p

of a process activity, but the appropriacy of per-

forming the task. The respective scale has four items

(not achieved, partially achieved, largely achieved,

and fully achieved). To reach a certain capability

level it is necessary to obtain the grade “largely

achieved” and for all process attributes of the levels

below the grade “fully achieved.” During the assess-

ment it is obligatory to prove that the requirements

of a certain step are met. The evidence can be shown

by the results of process activities or by interview

statements of the executors. Capacity levels are de-

termined for each process separately. The resulting

degrees of maturity describe a strengths-weaknesses

profile for potential improvements. The descriptions

of the next higher capacity level show opportunities

for process optimization.

The process and enterprise maturity model

(PEMM) was created by Michael Hammer in coop-

eration with the Phoenix Consortium and published

in 2006. The intention of the model is to check if the

prerequisites for changes in business process man-

agement are fulfilled. It also offers opportunities for

removing deficiencies and for measuring progress.

PEMM does not dictate what processes have to

look like in the sense of benchmarks and/or good

practices. It is driven by a pragmatic vision to help

companies plan and implement process-based trans-

formations. PEMM can be used universally, mini-

mizes additional effort, and may be applied even by

untrained employees. The client list shows global

presence with some focus on American enterprises.

The framework comprises two categories which

are interrelated: Process enablers (design, perfor-

mers, owner, infrastructure, and metrics) act as de-

terminants how well individual processes work.

Enterprise capabilities (leadership, culture, expertise,

and governance) apply to the organization itself. The

idea behind this segmentation is that organizations

need to offer supportive environments in order to

develop high-performance processes. The combina-

tion of the two categories is expected to provide an

effective way to plan and evaluate process-based

transformations. For this reason process enablers and

enterprise capabilities are broken down into four

levels of process enabler strength (P1 - P4) and four

levels of enterprise capability (E1 - E4). For both of

them, the scale for assessment consists of three items

(largely true, somewhat true, or largely untrue) that

can be visualized through traffic-light colors.

In the PEMM assessment, the weakest link of the

chain determines the maturity level: A certain level

can only be reached when all components show

appropriacy (a “somewhat true” somewhere is not

accepted). Besides, as an example, when the recep-

tiveness of an organization can be characterized by

E-2 capabilities, it is ready to advance its processes

to the P-2 level. Overall, PEMM represents a frame-

work with a stepwise structure that indicates a path

for becoming a process-based organization.

The Object Management Group (OMG), a con-

sortium for modeling (programs, systems, business

processes) and model-based standards, published the

Business Process Maturity Model (BPMM) in 2008

(still current version 1.0). Some team members were

co-authors of CMMI which explains the high simi-

larity between the two models. In contrast to CMMI,

BPMM concentrates more on transactional-oriented

business processes, better characterized as work-

flows across organizational boundaries. Neverthe-

less, BPMM can be mapped to CMMI.

BPMM distinguishes between five different ma-

turity levels. To operationalize the focus, each level

(except for level 1) is combined with categories and

process areas. The categories (organizational process

management, organizational business management,

domain work management, domain work perfor-

mance, and organizational support) represent a struc-

ture for the in total 30 process areas. Process areas

embody labeled sets of goals with a high-level pur-

pose. The goals specify the scope, boundaries, and

intent of each process area, and provide criteria by

which conformance to BPMM is evaluated.

Each process area contains the same set of five

institutionalization practices (describe the process,

plan the work, provide knowledge and skills, control

performance and results, objectively assure confor-

mance) and further specific ones. In order to support

organizations in their process performance improve-

ment efforts, (sub)practices, and illustrative exam-

ples are described.

BPMM is intended to be used for guiding busi-

ness process improvement programs, assessing risk

for developing and deploying enterprise applica-

tions, evaluating the capability of suppliers, and

benchmarking. All process areas comprise integrated

best practices that indicate what should be done, but

not how to put it into practice. On basis of apprai-

sals, BPMM offers an evolutionary staged approach

for continuous process improvement. There are sev-

eral options in form of four appraisal types (starter,

progress, supplier, and confirmatory). They differ in

the level of assurance that the practices of the frame-

work have been implemented appropriately.

5 EVALUATION OF MATURITY

MODELS

The intended goal was to define suitable evaluation

Evaluation of Maturity Models for Business Process Management - Maturity Models for Small and Medium-sized

Enterprises

%p

criteria and to present a first assessment of maturity

models to initiate a corresponding discussion within

the scientific community. Thus, this section contains

a description of eleven selection criteria for maturity

models important for SMEs in our point of view. For

the following literature based evaluation these cri-

teria will be applied to the selected models.

5.1 Selection Criteria

The maturity model must be universally usable (1),

because the companies of our SME target group

belong to different industries and a segmentation of

the maturity models would cause too much effort.

Since the focus of our paper is on maturity models

for BPM, they should contain differentiated

possibilities to evaluate single processes but also

cluster of processes (2). A very important criterion

for SMEs is that the maturity model can be de-

ployed on its own without external consulting

assistance (3). This implies that there is an encom-

passing description of the model available. Another

crucial criterion for SMEs is that the complexity of

the maturity model (4) is tailored to the need of

SMEs; that means a comprehensive and understand-

able description and straightforwardness of the mod-

el. For a broad categorization in different maturity

stages the maturity model should include quantita-

tive but also qualitative criteria (5).

Another criterion which refers to the deployment

of maturity models especially in SMEs is the level

of transparency and clarity of the evaluation

scale for the user (6). A success factor of the usage

of maturity models especially in SMEs is whether

the model offers concrete and understandable

action items for improvement (7) to reach the next

maturity stage after an evaluation cycle within the

model. Does the model offer possibilities for adap-

tations to specific circumstances of organizations

and processes (8) and is it flexible to changes?

Another criterion is the wide spread usage of the

maturity model (9) and availability of best practice

cases. If an SME decides to apply a maturity model

and puts some effort into this subject, it is important

to know if the model will be further developed by

a community (10) and if there are new releases

planned. The last criterion for the evaluation of

maturity models comprises two side effects: is there

any compatibility to other maturity models and is it

possible to acquire any kind of certificates (11)?

5.2 Evaluation Results

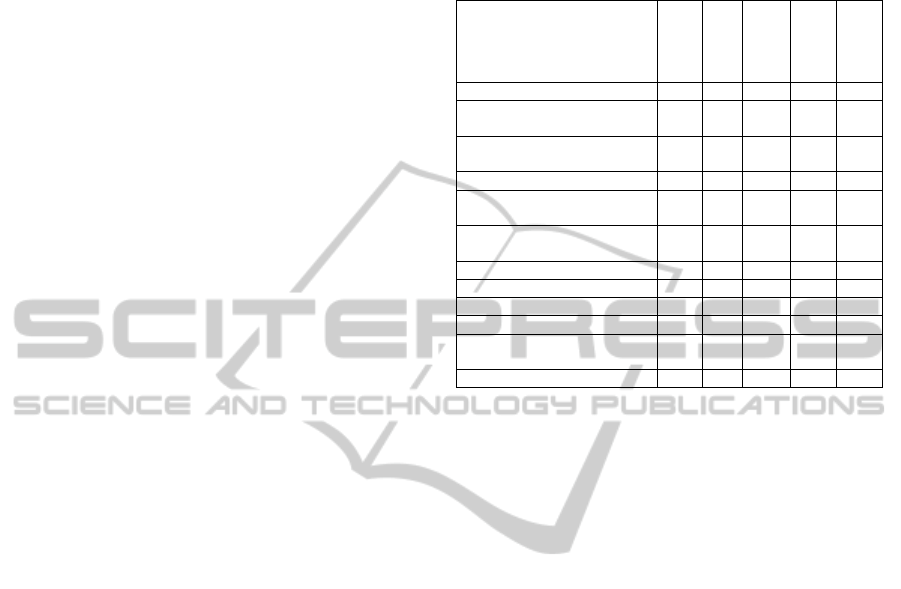

The following table contains the results of the evalu-

ation using a typical five-level Likert item (1 equals

“strongly disagree,” 5 equals “strongly agree”).

Table 1: Evaluation results of preselected maturity models.

Evaluation criteria

CMMI

EDEN

SPICE

PEMM

BPMM

(1) Universal usage

3

5

2

5

4

(2) Differentiated evaluation

model

5

5

5

5

2

(3) Usage without external

assistance

1

5

2

5

1

(4) Manageable complexity

3

4

3

4

3

(5) Quantitative and

qualitative criteria

3

5

3

5

3

(6) Understandable and clear

evaluation scale

2

5

2

4

1

(7) Concrete action items

4

4

5

5

5

(8) Flexible adaptability

1

2

1

1

2

(9) Wide spread usage

5

3

3

4

2

(10) Further development

5

5

5

3

1

(11) Compatibility and

certificates available

4

4

5

1

2

Total

36

47

36

42

26

The maximum score possible would have been 55

points. None of the selected models achieved this

number. We want to point out some important as-

pects of the four models with the highest scoring.

The maturity models CMMI and SPICE in joint

third place offer high compatibility (criterion 11: 4

and 5 points), but come together with a complex

evaluation scheme (criteria 4 and 6: 2 to 3 points).

Another minus point that has to be mentioned is the

high costs to implement the models which are not

acceptable for SMEs (criterion 3: 1 and 2 points).

The PEMM model offers easy practical usage, an

online-assessment and an understandable evaluation

scheme (criteria 3, 4, and 5: 4 and 5 points). Unfor-

tunately, the model does not offer adaption possi-

bilities to different scenarios in companies (criterion

8: 1 point); over the last couple of years there has

been no further development of the maturity model

(criterion 10: 3 points). Therefore, there is only lim-

ited relevance for SMEs.

The maturity model EDEN reached the highest

score in the evaluation. The model offers a high

practical relevance and will be continuously devel-

oped (criteria 3, 4, 5, 6, 10 and 11: 4 and 5 points).

Since on the website there are no best practice cases

available, the usage for SMEs has to be evaluated.

None of the evaluated models matched all cri-

teria for SMEs. Major areas of improvement in all

maturity models are seen in the flexibility of the

model, the transparency of the evaluation scheme

and the high complexity of the models.

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

%p

6 DISCUSSION

In order to illustrate the evaluation results, the

properties of the five examined maturity models are

discussed along a practical example in the following

sections. The example chosen is the hypothetical in-

troduction of “Anything Relationship Management”

(xRM) at an SME in the retail sector. xRM was se-

lected as a challenging “stress test” for the maturity

models because it covers three main aspects many

modern management concepts have in common: its

relative newness when quickly becoming popular

(“fashionability”), its strong IT component, and its

holistic approach involving the whole organization.

For more than two decades, IT supported rela-

tionship management has been one of the top priori-

ties for many large enterprises and SMEs. The trend

began with improving customer relations (CRM)

and continued with adapted concepts like Supplier

Relationship Management (SRM) and Employee Re-

lationship Management (ERM). In the last years,

xRM has emerged as a new approach which covers

the management of all stakeholder relations. xRM is

described as a combination of both a standardized

enterprise software platform and a managerial con-

cept to improve processes between all kinds of or-

ganizational entities (Britsch and Kölmel, 2011, p.

3).

However, studies have shown that often already

simple implementation projects of CRM systems

face substantial problems which lead to failure (see

e.g. Foss et al., 2008, p. 70 f.). Thus, especially in

the SME context, potentially more complex xRM

introductions need to be clearly structured. SMEs

have to evaluate their stakeholder status, strategy,

and roadmap before they invest in xRM software

platforms. They might work on customer processes

at first, and then, building upon this foundation, on

employee processes, supplier processes and so on.

Consequently, the use of a fitting maturity model is

essential for a successful xRM introduction.

If our retail SME selected BPMM, it would have

different options on how comprehensively processes

are appraised, and would be flexible concerning time

and money spent on these efforts. On the downside,

BPMM comes with a 482 page documentation and a

complex evaluation system. For a holistic xRM pro-

ject, BPMM deficits in process organization and the

negligence of IT process support would lead to diffi-

culties. Furthermore, it remains unclear if the OMG

will continue the development of BPMM.

As for SPICE, the SME would have a model

which offers ISO certification and allows the crea-

tion of a strengths-weaknesses profile to prioritize

fields of action. Self-assessment would be possible.

But since our example is in the retail sector, SPICE

does not fit – it is designed for process improvement

within technology companies. The different process

dimensions of the model do not cover all stakeholder

groups involved in the xRM concept. Still, for future

SPICE versions, expansions are planned.

By using CMMI, the SME would stick to the de

facto standard, which could have positive marketing

effects. Because the model is popular and freely

available for download, employees could already be

or easily become familiar with it. For xRM, the SME

could build on the customer oriented model version

CMMI for Services (CMMI-SVC, Version 1.3). Yet,

the model is not fully suitable for the retail sector

and the stakeholder approach of xRM. While CMMI

(like SPICE) is costly and needs external advisors,

concrete process implementation instructions are not

provided. For our SME with few resources applying

CMMI does not guarantee increasing performance.

With PEMM, the SME would have an xRM-

friendly, universal phase model for single projects as

well as for the whole firm. Its simplicity, intuitive

plausibility, and the small degree of formalization

offer a high attractiveness for SMEs. Also, PEMM

pays high attention to involving employees which is

crucial for relationship management introductions.

On the other side, the model is already several years

old and has reached its limits e.g. at depicting new

types of “many-to-many” xRM interactions in social

media. Besides, it does not offer any certifications

and cannot be integrated with other models.

In case our SME chose EDEN, it could use the

simplified self-assessment option for a convenient

evaluation. This could be the foundation for fast-

track benchmarking of xRM stakeholder processes.

A further benefit of EDEN lies in its compatibility

with other models: retail sector-specific questions

could be included through complementary modules.

However, EDEN lacks in detailed “procedures” and

“good practices.” Also, like with all selected models,

the flexibility of using EDEN itself (e.g. changing or

dropping criteria) is low, which may be inconvenient

especially for small companies.

Due to these shortcomings, none of the models

fits perfectly for SMEs. For further considerations it

therefore makes sense to initiate a BPM maturity

“consolidation” – a collaboration of several univer-

sities with firms and related institutions offers the

chance to reinforce a well-known and accepted

standard including good practices. In this way, the

advantages of the different maturity models could be

integrated under the perspective of SME require-

ments. Based on this model, we see big potentials in

Evaluation of Maturity Models for Business Process Management - Maturity Models for Small and Medium-sized

Enterprises

%p

deriving topic centered sub-models, like a version

for xRM introductions. Today, similar attempts can

be observed using available maturity models (e.g.

“CRM CMMI,” Sohrabi et al., 2010). The idea of

categorizing the amount of IT support offers further

opportunities: corresponding reflections lead to auto-

mated data collection where business processes are

supported e.g. by ERP systems (see e.g. Thomé, de

Hesselle, p. 546 ff.). Last but not least a tool-based

solution for an integrated maturity model would in-

crease efficiency in practice (see e.g. Hefke, 2008).

7 CONCLUSIONS

The overview has shown that the selected maturity

models cover a broad scope for business process

management. This drove us to the main question of

this article, which of them shows the highest

attractiveness for SMEs. The models PEMM and

EDEN scored highest in our evaluation. Yet, none of

models could fulfill the needs of SMEs completely.

This is why we propose the development of a busi-

ness process maturity model which is specifically

addressing the requirements of SMEs, as reflected in

our 11 appraisal criteria. In a second phase, this new

model has to be allied in practice and the fit for pur-

pose has to be evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Alexandra Kroll

und Stephanie Raytarowski. This paper represents a

further development based on the students' pre-

liminary work. The authors would also like to thank

the European Commission for the financial support

of the R&D project GloNet within the FInES cluster.

REFERENCES

Ahern, D., Clouse, A., Turner, R., 2004. CMMI distilled:

A Practical Introduction to Integrated Process Im-

provement. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

Britsch, J., Kölmel, B., 2011. From CRM to xRM: Mana-

gerial Trends and Future Challenges on the Way to

Anything Relationship Management. In: Cunningham,

P., Cunningham, M. (editors), eChallenges e-2011

Conference Proceedings.

Chrissis, M., Konrad, M., Shrum, S., 2006. CMMI Guide-

lines for Process Integration and Product Improve-

ment. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

Dombrowski, U., Brinkop, M., 2011. Der Prozesssicher-

heitsgrad zur Prozessbewertung. In: ZWF, Edition 106

(2011), pp. 400 - 406.

Foss, B., Stone, M., Ekinci, Y., 2008. What makes for

CRM system success – or failure? In: Database

Marketing & Customer Strategy Management. Vol.

15, No. 2, pp. 68-78.

Hammer, M., 2010. What is Business Process Mana-

gement? In: vom Brocke, J., Rosemann, M. (editors),

Handbook on Business Process Management 1.

Springer, Berlin and Heidelberg.

Harmon, P., 2010. The Scope and Evolution of Business

Process Management. In: vom Brocke, J., Rosemann,

M. (editors), Handbook on Business Process Mana-

gement 1. Springer, Berlin and Heidelberg.

Hefke, M., 2008. Ontologiebasierte Werkzeuge zur Unter-

stützung von Organisationen bei der Einführung und

Durchführung von Wissensmanagement. Dissertation,

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT).

Hofmann, H., Yedlin, D., Mishler, J., Kushner, S., 2007.

CMMI for Outsourcing: Guidelines for Software,

Systems, and IT Acquisition. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

Knuppertz, T., Schnägelberger, S.,Clauberg, K., 2010.

Umfrage: Status Quo Prozessmanagement 2009/2010.

BPM&O GmbH, Köln.

McCormack, K., Lockamy III, A., 2004. The Develop-

ment of a Supply Chain Management Process Maturity

Model Using the Concepts of Business Process

Orientation, http://www.supplychainredesign.com/

publications/scm-2004.pdf (01.23.2012).

Rosemann, M., de Bruin, T., Power, B., 2006. BPM

Maturity. In: Jeston, J., Nelis, J. (editors), Business

Process Management Practical Guidelines to Success-

ful Implementations. 2

nd

edition, Butterworth.

Schmelzer, H., Sesselmann, W., 2010. Geschäftsprozess-

management in der Praxis. 7

th

edition, Carl Hanser,

Munich.

Schnägelberger, S., 2009. EDEN – Reifegradmodell.

Prozessorientierung in Unternehmen. White Paper,

http://www.bpm-maturitymodel.com/eden/export/sites

/default/de/Downloads/BPM_Maturity_Model_EDEN

_White_Paper.pdf (11.12.2012).

Sohrabi, B., Haghighi, M., Khanlari, A., 2010. Customer

relationship management maturity model (CRM3): A

model for stepwise implementation. In: International

Journal of Human Sciences. Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1-20.

Thomé, R., de Hesselle, B., 2011. Betriebliche Prozess-

reifgradmodelle. In: Das Wirtschaftsstudium (WISU).

Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 544-550.

Zwicker, J., Fettke, P., Loos, P., 2010, Business Process

Maturity in Public Administrations. In: Handbook on

Business Process Management 2. Springer, Berlin and

Heidelberg.

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

%p