Approaching Knowledge Management in Organisations

Hilda Tellio

˘

glu

Institute of Design and Assessment of Technology, Vienna University of Technology, Multidisciplinary Design Group,

Favoritenstrasse 9-11/187, A-1040, Vienna, Austria

Keywords:

Knowledge, Knowledge Management, Organisations, Change Management.

Abstract:

The paper is about studying knowledge management practices in organisations. First we summarise the basic

definitions of knowledge and knowledge management. After showing several studies on knowledge manage-

ment in industrial context by stressing different classifications developed so far including our online survey we

introduce our approach to knowledge management in organisations. It is a spiral model illustrating knowledge

life-cycle in organisations which is relating different types of organisations (time-, product-, service-based) to

knowledge, volatility, and knowledge management. By doing so, business processes and the structure of or-

ganisations are considered. Special focus is given to specific individual and organisational knowledge created

and shared within and outside the organisational boundaries, impacts of different volatility factors to knowl-

edge, knowledge management processes, and change processes triggered by knowledge management practice

in organisations. Finally we conclude our paper by stressing our future work in this area.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the last decade the role of knowledge and knowl-

edge management got the whole attention of organi-

sations. It became clear that nowadays business pro-

cesses rely on this very critical economic resource.

Knowledge is unique selling proposition of organisa-

tions which makes them special. How knowledge can

be managed and integrated in business processes is

still an open issue for most organisations.

In the research and consulting literature there are

several definitions of knowledge (see Section 2) and

approaches with differing foci to knowledge manage-

ment (see Section 3). First of all, it is important to

understand how knowledge can be created, modified,

shared, and maintained in an organisational context.

Executive managers of companies are furthermore in-

terested in ways of application of knowledge man-

agement in their business domain to make available

knowledge and experiences persistent and accessible

for later use in their organisation. In particular, com-

panies want to know how they could deal with knowl-

edge management in their concrete business situation.

By current technologies and frameworks there is still

no big help provided to organisations for the identifi-

cation of their knowledge management elements and

other crucial impact factors, for the definition of their

own knowledge management processes according to

their business context, and for the establishment of

methods and supporting systems to manage the dy-

namic context-dependant changes in knowledge man-

agement.

In this paper, we want to show how we approach

this problem and what we suggest to deal with this

challenge. In our approach we see knowledge man-

agement integrated in the coordination activities in

an organisation. Our studies about coordination so

far show relevant evidence that organisations need to

manage their knowledge flow within and outside the

company boundaries. They have to define approaches

to deal with the dynamics of changes in an organ-

isation, which causes adaptions, improvisations, re-

actions to current practices, and most of all, regular

monitoring and planning of change processes at all

business levels.

First we want to summarise different definitions

of and approaches to knowledge and knowledge man-

agement (Section 2). Then we show several stud-

ies on knowledge management in industrial context.

We stress different classifications developed so far in-

cluding some relevant outcomes of our online survey

we established. In our survey we wanted to find out

the current understanding and use of social network

services by organisations for cooperation and sharing

with other companies (Section 3). After introducing

our approach as a spiral model of knowledge manage-

ment (Section 4) we conclude our paper.

208

Tellio

˘

glu H..

Approaching Knowledge Management in Organisations.

DOI: 10.5220/0004150002080215

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2012), pages 208-215

ISBN: 978-989-8565-31-0

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 KNOWLEDGE AND

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Knowledge is a bunch of “facts, feelings, or experi-

ences known by a person or group of people”

1

related

to context. Knowledge is the combination of infor-

mation, skills, experiences, and personal capability of

people (Baker et al., 1997). Knowledge can be found

in artefacts people produce, in communications they

carry out, at the places they work and live. So, it can

be related to people, products, processes, or culture.

Human behaviour and interactions with others – no

matter private or professional – are guided by knowl-

edge one has.

To understand knowledge and mainly to approach

it from scientific point of view and furthermore to

use it for design of systems, several categories have

been introduced so far. The most known distinction is

between implicit (tacit) (Polanyi, 1958) and explicit

knowledge (Bloodgood and Salisburny, 2001). Al-

though there are lots of differences between them,

they can be seen as two sides of the same coin be-

cause they are equally relevant for organisations (Va-

hedi and Irani, 2011).

Explicit knowledge can be easily expressed, better

codified and communicated than the tacit knowledge.

After writing down or just verbally it can be passed

to others. Furthermore, it can be acquired through

articulation and codification. It is then relative sim-

ple to transfer and imitate, like in case of product

characteristics or documented processes like account-

ing procedures and marketing strategies (Bloodgood

and Salisburny, 2001) (Raghu and Vinze, 2007). Be-

ing “practical knowledge that is key to getting things

done” (Vahedi and Irani, 2011, p.445) tacit knowl-

edge is difficult to capture, codify, communicate, and

retrieve. It can only be learned through experience

and by immersion. There are difficulties in expres-

sion and awareness of the existence of this kind of

knowledge by its possessor. This makes its manage-

ment very hard to almost impossible.

Some research has been done on knowledge ac-

quisition and transfer by focusing on communication

and networking technologies (Bloodgood and Sal-

isburny, 2001) (Raghu and Vinze, 2007). Implicit

organisational routines or generally accepted back-

ground understandings and competitive strategies are

some examples of this kind of knowledge. Parts

of this knowledge are called “experiential knowl-

edge” (Seethanraju and Marjanovic, 2009) and can

be shared, e.g., in processes of collaborative prob-

lem solving or when people experience the same. We

1

Collins English Dictionary, 1991, p. 860

can find further definitions in the literature according

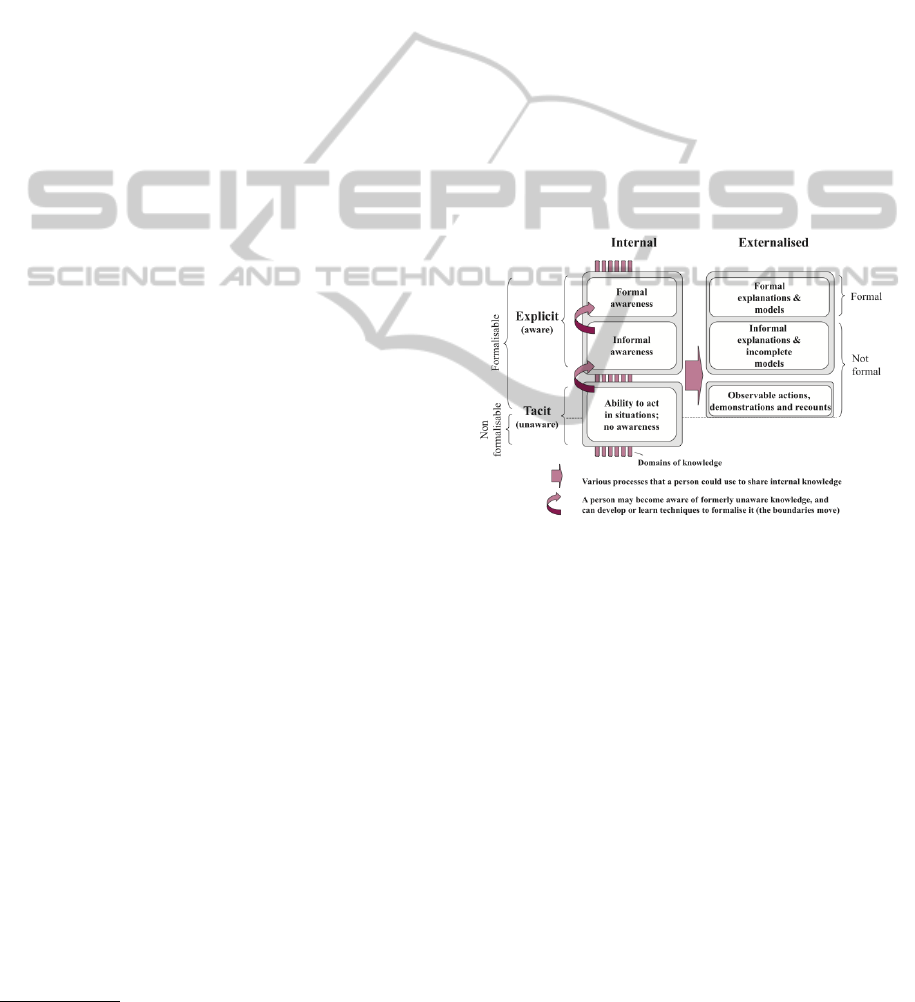

to the following criteria (Kalpic and Bernus, 2006):

awareness of (explicit or tacit) knowledge (can a per-

son explain it or is he/she just able to show it), in-

ternalised or externalised knowledge (has an external

record been made, e.g., written text, drawings, mod-

els), formalised or not-formalised knowledge (is the

external representation of the knowledge in a consis-

tent and complete form). Figure 1 shows the categori-

sation of knowledge based on these criteria (Kalpic

and Bernus, 2006). An interesting interpretation leads

to the assumption that tacit knowledge can be trans-

formed into informal explicit knowledge (by con-

versation, sharing common experiences, or other ap-

proaches) and this may be converted into formal ex-

plicit knowledge (Kalpic and Bernus, 2006). The

question still remains whether the context in which

this can happen has an impact on this type of trans-

formation of implicit to explicit knowledge.

Figure 1: Knowledge categories by Kalpic and Bernus

(2006).

So far we were mainly referring to individual knowl-

edge, also called content knowledge by Holsapple and

Joshi (2002). Being embodied in usable represen-

tations, which are mainly artefacts, content knowl-

edge can be preserved, transferred, and shared across

organisational boundaries (Tellio

˘

glu, 2012). This

tickles other types of challenges in knowledge man-

agement, namely managing organisational or collec-

tive knowledge. This type of “schema knowledge”

(Seethanraju and Marjanovic, 2009), which can be de-

scribed in terms of knowledge embedded in the cul-

ture, infrastructure, purpose, and strategy of an organ-

isation (Kalpic and Bernus, 2006), is represented or

conveyed in the working of an organisation (Kalpic

and Bernus, 2006). Here again, artefacts play an im-

portant role for capturing and preserving it. In organi-

sational settings it is important to consider how to deal

with this type of knowledge. One way to approach

this is to apply knowledge life-cycles.

ApproachingKnowledgeManagementinOrganisations

209

Knowledge has to flow by being acquired, shared,

or exchanged to generate new knowledge, otherwise

the existing knowledge ages and becomes useless.

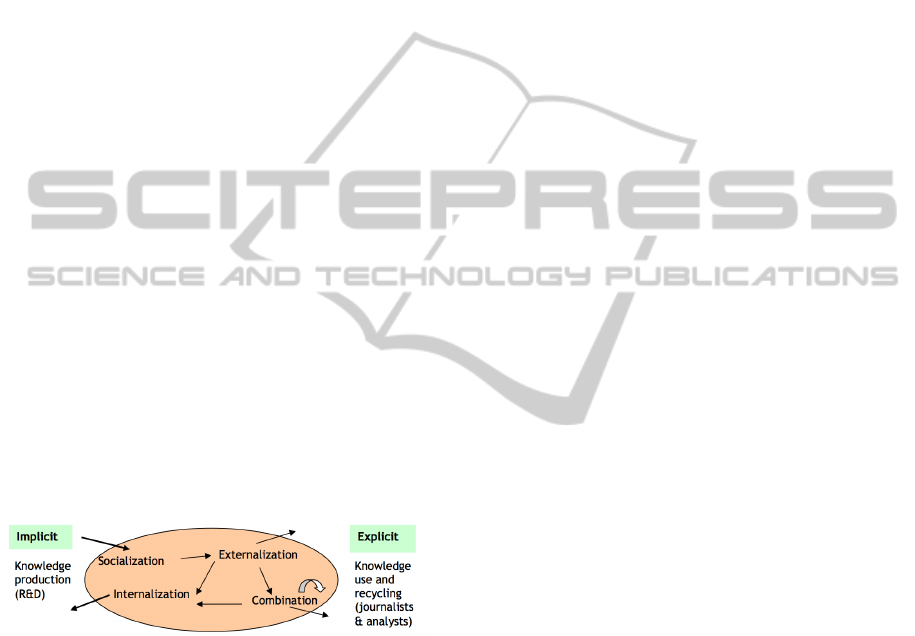

Therefore, Nonaka and Takeuchi developed the life-

cycle of knowledge, which consists of the following

four phases (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) (Kalpic and

Bernus, 2006) (Vahedi and Irani, 2011) (Alavi et al.,

2010) (Figure 2):

• Socialisation – Tacit to Tacit Knowledge: This

is the process of transferring tacit knowledge from

one individual to another in communities of prac-

tice and interest. This can happen through ob-

servation or working together with someone more

skilled or knowledgeable.

• Externalisation – Tacit to Explicit Knowledge:

The process of externalisation takes place if an

individual generates explicit knowledge from her

or his tacit knowledge. Examples are documen-

tation, verbalisation, or if new best practices are

chosen from informal work practices.

• Internalisation – Explicit to Tacit Knowledge:

Individual tacit knowledge can be created through

the internalisation of explicit knowledge by learn-

ing and training.

• Combination – Explicit to Explicit Knowl-

edge: Combination means the generation of

explicit knowledge through the combination of

existing explicit knowledge. This action sup-

ports problem-solving and decision-making, e.g.,

through the application of data mining techniques.

Figure 2: Knowledge life-cycle by Nonaka and Takeuchi

(1995).

After recognising knowledge as an important eco-

nomic asset, business and scientific professionals

started to study how to deal with knowledge in com-

plex environments like organisations and in more

and more connected cooperative settings. Knowl-

edge management enables capture, store, exchange,

and retrieve valued information for all relevant stake-

holders and through this facilitate the base for in-

formed decisions. In management science, knowl-

edge management is defined as the active manage-

ment of knowledge in an organisation by using sys-

tematic processes. Human resource management de-

fines knowledge management as a necessary endeav-

our to transport knowledge from those who have it

to those who needs it. Besides increasing efficiency

and using multiple knowledge sources effectively to

create a competitive advantage, one of the most im-

portant requirements organisations have is to keep

knowledge in the organisation, no matter what hap-

pens, even if employees leave the company or coop-

erations are conducted with other – probably compet-

itive – organisations. The organisational and techni-

cal environment must be setup in ways that allows

knowledge flow through all the different phases of its

life-cycle. Knowledge management must support that

goal (Vahedi and Irani, 2011).

For the management of knowledge many re-

searchers defined some elementary strategies, frame-

works, activities, and phases. Davenport and Prusa

identified four knowledge processes: knowledge gen-

eration (creation and acquisition), knowledge codi-

fication (storing), knowledge transfer (sharing), and

knowledge application (transitions between knowl-

edge types) (Kalpic and Bernus, 2006). Another ap-

proach defines knowledge sharing, knowledge utili-

sation, knowledge storage, and knowledge refinement

as the main activities for knowledge management

in organisations. Knowledge sharing means the ex-

change between individuals and groups, while knowl-

edge utilisation includes all activities of the applica-

tion of knowledge in business. Furthermore, knowl-

edge refinement is the filtering and optimising of the

knowledge, which is saved in the organisational mem-

ory at knowledge storage (Alavi et al., 2010).

Alavi and Marwick identified acquisition, index-

ing, filtering, classification, cataloging and integrat-

ing, distributing, and application respectively knowl-

edge usage as the major knowledge management ac-

tivities (Alavi and Marwick, 1997). Procure, or-

ganise, store, maintain, analyse, create, present, dis-

tribute, and apply are the more detailed activities for

knowledge management, which were presented by

Holsapple and Whinston (Holsapple and Whinston,

1987). Four essential knowledge manipulation activ-

ities, which were defined by Holsapple and Joshi are

acquiring, selecting, internalising, and using (Kalpic

and Bernus, 2006). A further approach is about

knowledge storage and retrieval, knowledge sharing

and knowledge synthesis as the phases essential for

knowledge management (Raghu and Vinze, 2007).

3 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

IN INDUSTRIAL CONTEXT

The “technology-push model of knowledge manage-

ment” was criticised by some researchers because

it underestimates the process of knowledge manage-

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

210

ment in organisations. Storing the organisational data

is not enough to maintain and guarantee knowledge

management in such an environment, especially when

it means that the right persons should get the data at

the right time (Vahedi and Irani, 2011). However,

emerging technologies and communication channels,

like messaging, texting, micro-blogging, or blogging,

offer new ways to deal with the distribution and cap-

turing of knowledge. They, at the same time, facilitate

an easier handling of tacit knowledge in organisations

(Vahedi and Irani, 2011).

Chan and Chao studied knowledge management

in practice in small and medium-sized organisations

(Chan and Chao, 2008). The most SMEs started

with knowledge management because of its success

in other organisations. The main goal was to increase

the profit, to reduce the costs by avoiding duplicated

work, and through this to gain competitive advan-

tage. Only 16% could encourage innovation by ap-

plying knowledge to existing resources. Examples of

reasons for failure in applying knowledge manage-

ment in SMEs are the resistance by the employees,

poor knowledge management systems, or the false as-

sumption that the IT department is able to transform

a knowledge management vision into a knowledge

management system including all activities and pro-

grams (Chan and Chao, 2008). The result of this study

is that there is still the need to continue the knowledge

management research in organisations to develop bet-

ter understanding, better methods, and so, more flex-

ible and suitable approaches to knowledge manage-

ment in such complex cooperative settings.

Kankanhalli et al. studied 20 successful com-

panies representing a variety of industrial contexts

(Kankanhalli et al., 2003). They classified the or-

ganisations along two dimensions: product-based ver-

sus service-based and high- versus low-volatility con-

text (p.69). Volatility refers to the change processes

in a company which is seen in a multidimensional

context including technological, regulatory, sociocul-

tural, and economic. If knowledge is time-sensitive

then the volatility is high, so knowledge must be up-

dated regularly and made available to all who needs it.

Besides deriving implications for practice, Kankan-

halli et al. tried to categorise these different four

types of organisational settings in relation to a knowl-

edge management approach (Kankanhalli et al., 2003,

p.73). The categories were codification versus per-

sonalisation levels in a low to high scale. This is

a purely industry classification without considering

knowledge management strategies and IT support in

detail. Though, it helps to systemise the knowledge

management arena in an organisation.

Calabrese and Orlando defined 12 steps to imple-

ment a knowledge management system to provide a

framework and methodology for the implementation

of a management system in organisations (Calabrese

and Orlando, 2006). The second step is about con-

ducting work-centred analysis followed by planning

actions on a higher level to communicate by the lead-

ership with senior management. It is done by the

leadership because it is strongly related “to the culti-

vation of business strategy through the driving of val-

ues for knowledge creation and sharing” (Smuts et al.,

2009, p.72). It is a crucial process because it values

the main elements of an organisation, like individual

ways of dealing with work, communication and co-

operation patterns established. A thorough contextual

inquiry is needed (Beyer and Holzblatt, 1998), espe-

cially from all relevant parts of the organisation. This

avoids overseeing certain work practices or ignoring

certain communities of practice. A special attention

must be given to gather data about and from people

who are the real workers, and not managers. Exper-

tise of real workers embed valuable information about

knowledge they have, and how they apply their tacit

knowledge at work. If this type of data can be cap-

tured consistently and in detail – which is very diffi-

cult – the most challenging part of knowledge acqui-

sition is done.

Smuts et al. (2009) wanted to proof the concept

of 12-step process by Calabrese and Orlando (2006).

They ended up in a framework and methodology for

the implementation of a knowledge management sys-

tem. The methodology procedure is composed on a

rather abstract level around five framework compo-

nents: strategising, evaluation, development, valida-

tion, and implementation. After studying their ap-

proach in a real company, they showed that each step

of the methodology maps at least to one of the steps

defined by Calabrese and Orlando (2006). Unfortu-

nately, the study was not large enough and not consid-

ering different types of organisations with their spe-

cific contexts, so they could not generalise the frame-

work and the methodology they created.

One of our own studies based online surveys in

this area delivers interesting results and helps under-

stand organisational context with respect to knowl-

edge management and sharing

2

. We wanted to find

out what the current understanding of social network

services (SNS) and their private and professional use

is. Besides some information about the person, the

company, the area of business, etc., the online survey

contained 31 questions on the popularity and avail-

ability of SNS for private and professional use, on

areas of application with the duration of use, moti-

2

The online survey was developed and used in the scope

of a master’s thesis (Klemen, 2012).

ApproachingKnowledgeManagementinOrganisations

211

vation, features used, integration into the daily work,

and possible impacts on one’s own work processes.

After two months we had 282 answers that we could

use for evaluation and analysis. Some of the interest-

ing results are: Organisations use only certain SNS

and applications, like Skype, blogs, Windows Live

Spaces, RSS feeds. Skype, mainly its IP-based tele-

phony feature, is the most and longest used appli-

cation for communication. 68% mean that the col-

laboration with other organisations or partners is the

same with SNS as it was without using them, whereas

31% see an improvement in collaboration processes

when SNS are applied. Among the ones who found

that SNS improve the collaboration processes, 30%

found that SNS speed everything in business organ-

isation and work processes, and the coordination of

work becomes easier. 21% found that the distribu-

tion of work can be carried out faster and easier, and

additional 18% meant that there are other advantages

of the use of SNS in organisations. 41% perceived

that SNS ease the cooperation at all. 73% would

recommend the use of SNS in business processes to

their existing and new partners. 64% would use SNS

again in the future projects, 15% would not use them

any more. An interesting outcome of the survey is

that 66% of the SNS users want to separate their pri-

vate contacts and exchange with others from the ones

which are work-related, whereas 16% currently make

no difference between private and professional, but

can imagine to do that in the future, and 18% do not

see the need to separate them.

4 THE SPIRAL MODEL OF

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Previous sections showed that there is a correlation

between business processes and knowledge manage-

ment. We know that organisations host structured

predictable and unstructured situated processes at the

same time. The degree of structuredness of a pro-

cess is dependant on the knowledge available to carry

out the particular activities included in processes. If

unexpected contingencies arise in work practices re-

sponses must be given in an ad-hoc manner consider-

ing the circumstances in which the processes must be

carried out.

Based on the research, studies, and findings in sev-

eral ethnographic case studies in different companies

within an European research project called MAPPER

(Schmidt et al., 2009), we first want to show how or-

ganisations can be characterised depending on their

main activities, business focus, and organisation of

work. After analysing our findings in our studies, we

ended up in differentiating time-, product-, or service-

based organisations. These types help analyse the

organisational context and economic, environmental,

cultural circumstances in which the organisation has

to exist.

The differentiation between product- and service-

based organisations was also made by Kankanhalli et

al. (2003). They used this classification only to dif-

ferentiate between high and low volatility, and lev-

els of competition in industrial context. They did

not describe or analyse the processes within organisa-

tions. They aimed to understand the relation between

knowledge and volatility in different types of organi-

sations. We, on the other hand, try to define and anal-

yse processes, management, coordination and coop-

eration issues, success factors in such organisations,

by focusing on knowledge management processes to

provide support for organisations. In our studies we

identified that some organisations are mainly driven

by time and time-dependant duties or deliveries. So,

we add to the two categories the time-based organisa-

tions.

In time-based organisations deadlines and tempo-

ral conditions drive the activities. The end delivery

date is used to define the logical and temporal order

of activities in a specific project. The allocation of

human and non-human resources is done in line with

the time-based work plan created. For cases of unex-

pected contingencies, there must be a temporal space

for improvisations, which may also trigger changes in

business processes. Simultaneity and ad-hoc changes

in resource allocation are common in such environ-

ments. Decisions are mainly made distributed. Be-

sides for coordination of work meetings are used to

up-to-date the project progress and, in case of trou-

bles, to reallocate resources. Success is achieved

mainly if deadlines are met, and of course, only if the

expected results are delivered in expected quality.

In product-oriented organisations the product is

central. Its design, development, and maintenance

define the organisational and work-related structures.

All activities are arranged around the product in at-

tention. If it is a complex product, it is normally di-

vided into parts, which are assigned to different per-

sons, work groups, or even companies. Interfaces be-

tween parts must be defined which is normally a dy-

namic process. They can be changed, adapted, and

revised several times in the course of the production

process. Interdependencies between product parts de-

termine the coordination of work in the whole project.

On the one hand, the implementation of the inter-

faces agreed on, on the other, the timeliness in deliv-

ering the planned parts in planned quality and quan-

tity are main issues of coordination protocols. Project

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

212

managers deal with these interface definitions and de-

pendencies between the productions. They create a

plan which maps the product structure and assigns to

groups or individuals. Monitoring of the progress of

work on product parts, interventions in case of prob-

lems, and reallocation of resources, if necessary, de-

pending on the availability are common. Changes in

work processes or work assignment occur depend-

ing on personal, technical, commercial, complexity-

related, or strategic problems that may arise. Not only

to solve such problems, but also to bring different

groups together to exchange their work progress and

other issues relevant to all, regular meetings are es-

tablished. Configuration management tools or other

central common information spaces are used as co-

ordinative artefacts enabling standardisation of proto-

cols. Decisions are made centrally involving the re-

sponsible persons for the product parts letting them to

negotiate their open issues. Success is measured in

the quality of the product, in its integrity, complete-

ness, and unity.

If organisations are service-based, processes are

central in the entire business. Services are valuable

results of usually predefined, well structured, and in

most parts routine processes. Several groups are as-

signed to tasks. A workflow or likely system is used to

model the processes and to monitor them in real time.

It is the only coordinative construct by providing the

coordinative protocols. If there are deadlocks or prob-

lems in carrying out certain tasks in the workflow,

project managers intervene and reallocate resources

or reassign people to tasks. In a supply chain or

customer relationship, coordination of work goes fur-

ther to externals like customers, suppliers, distributed

teams from other locations, etc. The system used em-

bodies the coordination mechanism. It enforces peo-

ple to do certain things in a certain order. To skip or

postpone a task is almost not possible. Modifications

of workflow can be done in some cases, but normally

not in an ad-hoc manner. Improvisations are difficult

or impossible. In case of contingencies, the coopera-

tive work is coordinated directly by people involved,

which is not coupled to the system used. In routine

work, decisions are made centrally which may then

modify the workflow system. People carrying out the

work are not included in decision processes. Success

is measured in the workflow system. A project of this

kind is successful if work processes are carried out

according the workflow in an efficient way, so the ser-

vices are delivered at the right time to the right people.

Depending on the type of an organisation changes

are needed over time, not only in processes, peo-

ple, products or services, but also in requirements

to supporting elements of an organisation, like ICT,

work environments, conventions and norms, work and

coordination protocols, knowledge management pro-

cesses, etc. Organisations often do not know how to

deal with the volatility context they are in, and with

their knowledge and change management practices,

especially when changes initiated internally or exter-

nally occur technologically, regulatory, sociocultural,

or economic. Current practices need to be evaluated.

If there is a need for change, plans need to be made

to adapt the organisation on all related levels. Knowl-

edge plays here a crucial role. Experiences of past

activities and knowledge gathered so far help decide

what has to be done to improve or keep best practices

in organisations.

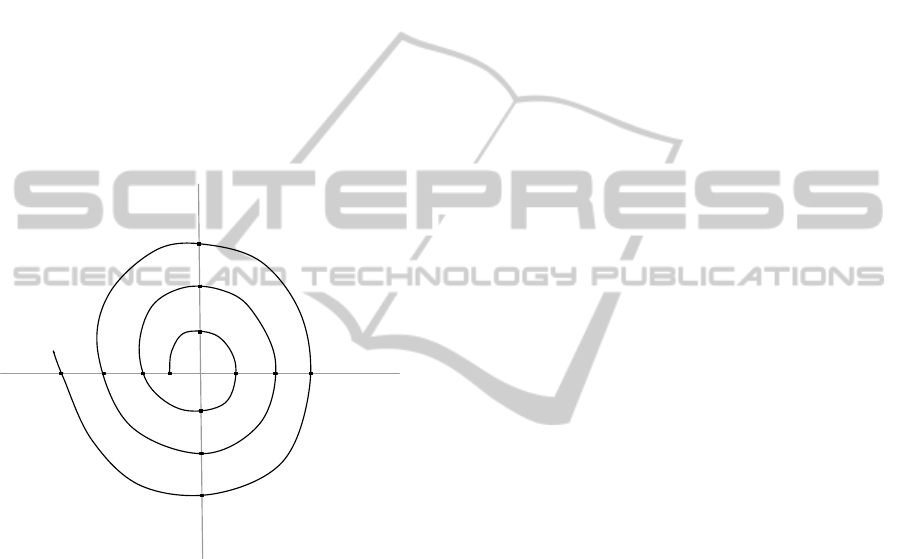

This sketches a complex process which changes

over time. We claim that a knowledge life-cycle can

help researchers and the organisations to understand

the multilayered impact factors in an organisation and

its dynamic elements (Figure 3):

1. The model starts with the identification of the or-

ganisation as a time-, product-, or service-based

one. This leads to a first definition of business pro-

cesses and related artefacts and coordination pro-

tocols. This is something which happens anyway,

sometimes intentionally sometimes implicitly by

just starting with work processes.

2. The next step is to find out and reflect on knowl-

edge generated in the organisation. What types

of individual knowledge is created and shared?

What are the characteristics of the content knowl-

edge related to products, services, or processes?

To which degree is the content knowledge explicit

or implicit, internal or externalised, formal or in-

formal?

3. After a certain period of time it is important to

capture the volatility factors in the organisation.

How can the organisations’ culture, infrastructure,

purpose, and strategy be described? What arte-

facts are used to manage this schema knowledge?

Is there enough information to analyse risks and

create possible contingency plans? Is a certain

change needed? If yes, where and to which de-

gree?

4. Knowing the change requirements and the current

organisational context, the organisation can start

to establish knowledge management processes.

Are there differences between parts of the organi-

sation with respect to knowledge management? If

there are, what can be the appropriate knowledge

management practice for each of them? What are

the socialisation, externalisation, internalisation,

and combination processes needed?

5. Now, it is time to reflect on all issues and pos-

ApproachingKnowledgeManagementinOrganisations

213

sible answers gathered so far on organisational

level. How is the knowledge management cur-

rently provided in the organisation? Is knowl-

edge management efficient, accepted by individ-

uals, and successful? Is there a need to change

knowledge management processes? Are there

emerging reasons to modify knowledge manage-

ment practices in the organisation? What parts of

knowledge management (i.e., knowledge genera-

tion, codification, transfer, or application) do need

adaptations? What are the impacts of changes

planned on business processes? What are the con-

sequences of changes so far?

So then the circle continues with the step 2 described

above. Each time it is a little bit different, depending

on all the factors changing over time.

Organisation Knowledge

Volatility

Knowledge

Management

t=0

t=1

t=2

t=3

t=4t=n

Figure 3: The spiral model for knowledge management in

organisations.

To show the dependencies between the factors ques-

tioned above we now introduce the spiral model of

knowledge management in organisations (Figure 3).

The model illustrates a knowledge life-cycle which

is relating different types of organisations (time-,

product-, service-based) with knowledge, volatility,

and knowledge management. Business processes and

the structure of organisations are considered. Spe-

cial focus is given to specific individual and organisa-

tional knowledge created and shared within and out-

side organisational boundaries, impacts of different

volatility factors to knowledge, knowledge manage-

ment processes, as well as change processes triggered

by knowledge management practice in organisations.

In our spiral model, we see a pattern in organi-

sational life-cycle if it comes to knowledge manage-

ment. Depending on the organisational type (time-,

product-, or service-based) certain amount of knowl-

edge is created and exchanged. The type, quality, and

characteristics of knowledge used in an organisation

changes in the course of work processes, depending

on products or services it provides, circumstances un-

der which work processes are carried out, economic

and technical factors having impact on activities and

processes.

Another important factor which causes changes or

risk for organisations is the volatility factor. Volatility

has impact on the amount and lifetime of knowledge

managed in an organisation, which again is dependant

on the dynamics in product or service development,

or the temporal constraints given to a project. The

degree of volatility influences the ways how knowl-

edge is created and handed over between actors in-

volved. If the product is an innovative one with com-

ponents which are new or delivered by others like

suppliers, the volatility is assumed rather high. In

such settings, problems can occur, e.g., related to de-

livery time, quality, and compatibility of the com-

ponents of a product. On the other hand, there are

companies offering products of which production and

maintenance are predictable. An organisation with its

schema knowledge and the certain degree of volatility

for a representative period of time needs knowledge

management for codification (externalisation) or per-

sonalisation (internalisation) or combination of indi-

vidual and collective knowledge.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we showed how knowledge management

can be approached in an organisation considering the

business processes, structure, specific individual and

organisational knowledge created and shared within

and outside the organisational boundaries, impacts of

different volatility factors to knowledge, knowledge

management processes, change processes triggered

by knowledge management practice, etc. This is a

first step to approach knowledge management in or-

ganisations by being aware of the dynamic character

of knowledge management, especially in high volatil-

ity environments. We want to show that time plays

a crucial role in knowledge management practices,

that it is important to reflect on and adapt knowledge

management processes in an organisation regularly by

actively analysing the different types of knowledge

created, modified, and shared in an organisation as

well as cultural, infrastructural, social, and strategic

changes happening in an organisation.

This spiral model can be seen currently as an ap-

proach or a framework that presents factors to con-

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

214

sider if it comes to establishing best practice knowl-

edge management processes in organisations. We

know that organisations need more than just a frame-

work. They need tools utilising different steps of

the model as much as possible integrated in the daily

work processes. With a minimum effort they should

be able to capture, analyse, plan, communicate, and

change knowledge management processes in their or-

ganisations. That is exactly what we plan to further

design and develop.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M. and Marwick, P. (1997). One Giant Brain. Har-

vard Business School, Boston.

Alavi, S., Wahab, D. A., and Muhamad, N. (2010). Explor-

ing the relation between organizational learning and

knowledge management for improving performance.

Information Retrieval and Knowledge Management,

pages 297–302.

Baker, M., Baker, M., Thorne, J., and Dutnett, M. (1997).

Leveraging human capital. The Journal of Knowledge

Management, 1:63–74.

Beyer, H. and Holzblatt, K. (1998). Contextual Design.

Defining Customer-Centered Systems. Morgan Kauf-

mann, San Francisco, USA.

Bloodgood, J. M. and Salisburny, W. D. (2001). Under-

standing the influence of organizational change strate-

gies on information technology and knowledge man-

agement strategies. Decision Support Systems, 31:55–

69.

Calabrese, F. A. and Orlando, C. Y. (2006). Knowledge

organisations in the twenty-first century: Deriving

a 12-step process to create and implement a com-

prehensive knowledge management system. Journal

of Information and Knowledge Management Systems,

36(3):238–254.

Chan, I. and Chao, C.-K. (2008). Knowledge management

in small and medium-sized enterprises. Communica-

tions of the ACM, 51:83–88.

Holsapple, C. W. and Whinston, A. B. (1987). Knowledge-

based organizations. The Information Society,

5(2):77–90.

Kalpic, B. and Bernus, P. (2006). Business process model-

ing through the knowledge management perspective.

Journal of Knowledge Management, 10:40–56.

Kankanhalli, A., Tanudidjaja, F., Sutanto, J., and Tan, B. C.

(2003). The role of it in successful knowledge man-

agement intitiatives. Communication of the ACM,

46(9):69–73.

Klemen, S. (2012). Auswirkung von Social Networking im

betrieblichen Gesch

¨

aftsumfeld. Master’s thesis, Vi-

enna University of Technology, Faculty of Informat-

ics, Multidisciplinary Design Group, Karlsplatz 13,

A-1040, Vienna, Austria.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-

Creating Company. How Japanese Companies Create

the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press,

New York.

Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-

Critical Philosophy. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

Raghu, T. S. and Vinze, A. (2007). A business process con-

text for knowledge management. Decision Support

Systems, 43:1062–1079.

Schmidt, K., Tellio

˘

glu, H., and Wagner, I. (2009). Ask-

ing for the moon. or model-based coordination in dis-

tributed design. In Proceedings of the 11th Euro-

pean Conference on Computer Supported Coopera-

tive Work (ECSCW’09), pages 383–402, Vienna, Aus-

tria.

Seethanraju, R. and Marjanovic, O. (2009). Role of process

knowledge in business process improvement methol-

ogy: A case study. Business Process Management

Journal, 15:920–936.

Smuts, H., Merwem, A. v. d., Loock, M., and Kotze, P.

(2009). A framework and methodology for knowledge

management system implementation. In Proceedings

of SAICSIT’09, pages 70–79.

Tellio

˘

glu, H. (2012). About representational artifacts and

their role in engineering. In Viscusi, G., Campagnolo,

G., and Curzi, Y., editors, Phenomenology, Organi-

zational Politics and IT Design: The Social Study of

Information Systems, pages 111–130. IGI Global.

Vahedi, M. and Irani, F. N. H. A. (2011). Information

technology (it) for knowledge management. Procedia

Computer Science, 3:444–448.

ApproachingKnowledgeManagementinOrganisations

215