Trust Online for Information Sharing

Cat Kutay

Computer Science and Engineering, The University fo New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Keywords: Indigenous Knowledge, Community Narrative, Information Networks.

Abstract: The use of the Internet for information sharing between government departments and between government

and community organisations is growing. However the issue of trust needs further study as this

communication could benefit from Web 2.0 technologies. This project was initiated by a network of

Indigenous people in government and community who wished to make more efficient use of information

sharing online, without people external to the culture and aspirations being able to influence the content, or

comment on the work being shared. The culture has a strong protocol for sharing information or knowledge,

and this is rarely valued outside this community. Furthermore, the experience as a minority culture within a

colonised society has increased the caution in public display of people’s interests or concerns.

1 INTRODUCTION

Trust is not just about willingness to share but also

about the value of what we share. For Aboriginal

people in NSW the decision about what is important

information is different to those in the mainstream

culture. While Federal Government has been

concerned with privacy issues around sharing of

information under Web 2.0, there needs to be more

consideration of the type of information different

cultures share, and to support that. This includes the

need to inhibit the sharing of information that is not

acceptable to minority cultures, such as respecting

periods of mourning.

The project for the development of suitable web

services for Aboriginal information and knowledge

sharing in NSW was developed around the following

community needs:

1. Community projects often receive Government

funding and wish to share the success, and the

reason for their success, with others who run similar

projects. Also Indigenous government workers need

to be able to analysis these projects to improve the

support they give. This requires the development of

repositories for knowledge access and extraction.

2. Organisational learning involves the retention

and linking of tacit knowledge. The use of audio

recordings to retain and share knowledge is

preferred by many indigenous groups and provides a

more accessible form of recording tacit knowledge.

3. University involvement in the project originated

with a community request to support knowledge

sharing protocols with software and to research how

these traditional communication methods may

provide new perspectives on Internet sharing.

4. Government and community workers wish to

share information on upcoming events, jobs, projects

and funding options. This required a communication

interface and analysis of information presentation

for online sharing

We describe briefly the first three projects to provide

the context to the research, but the main focus is the

fourth project dealing with information sharing.

2 COMMUNITY PROJECTS

In previous work we developed a conceptualisation

of search engines and artefact annotation in an

online community used for Indigenous knowledge

sharing (Kutay, 2011). We extended the work of

Pirolli and Card (1997) focusing on enhancing the

information retrieved, rather than seeing the search

result as the final ‘feed’ of the scavenger. We based

the design on a traditional form of knowledge

interchange in community learning, the corroboree,

or story telling through dance, performance and

music.

The corroboree format is hard to envisage online,

as in real life the process requires many hours of

216

Kutay C..

Trust Online for Information Sharing.

DOI: 10.5220/0004162902160222

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2012), pages 216-222

ISBN: 978-989-8565-31-0

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

preparation by the elders gathered to organise the

ceremony. We considered how community meetings

prior to the ceremony organise the ‘performance’

that provides the knowledge sharing. During the

preparation they discuss their desires: the context of

the corroboree, what is significant in the present

situation for the people, which is related to user’s

desires within the environment. They evaluate the

community’s goals and beliefs: this involves

considering the themes that need to be covered for

learning about the present context, which links to the

audience’s goals. They interpret and interact with

this environment: this develops the cohesion of the

narrative, what will be presented for the social and

creative linkage of information. Thus they decide

what will be performed.

Once this corroboree has started individuals

contribute stories or songs relating to how their own

knowledge fits into the previous narrative and so

select the stories that are shared.

2.1 Taking the Concept Online

In the online environment there are no ‘elders’ or

over-arching knowledge holders to link the results of

an online search into coherent knowledge. In present

search engines the system provides isolated packets

from which the user has to draw sense. The project

for coherency of isolated knowledge packets online

used tools for providing (cf. Rogers and Scaife

2007):

Knowledge representations within the real world,

providing a real performance;

Re-representation of information in various

format such as images, or use of audio and text

annotation;

Thematic support for searching through domain,

temporal and spatial sorting; and

Graphical context for the user’s search activity.

The design concepts that we developed from these

approaches were divided into the three main

activities on the portal. Firstly the user searches for

relevant material. Then within the results of that

search they want to explore the search results,

including any accessible annotations attached to

these artefacts. Finally they may want to add their

own annotations and notes for future searchers.

The issues that arose in the design of Indigenous

sites were the need to promote (Kutay, 2011):

Trust – knowledge can be misused or

misinterpreted if used out of context,

Access – ability to receive feeds particularly

suitable for mobile access is vital for many users,

Language – the language used on sites must be

simple written English or audio,

Immersion – a ‘modern’ look to the site with

links to social networks, ease of navigation and

practical presentation of the themes

Relevance – the interface, choice of content

matter, and the way information could be handled on

the site had to be relevant to the culture of the users.

3 ORGANISATIONS

In Australian and North American Aboriginal

groups the oral tradition is a skill learnt and passed

on as a discipline, involving repetition, praise and

critique (Rosenzweig and Thielen, 1998) to train the

young in this method of knowledge retention and

information sharing. Yet the importance of

Aboriginal oral memories in terms of retaining a true

history of Aboriginal collective identity and

knowledge is generally denigrated in the non-

Aboriginal view, as oral records are perceived as

coloured by personal experience (Mellor, 2001), and

in constant flux.

The online sharing and comparing of stories to

provide both a commonly agreed, stable and

accessible record of knowledge is an important

aspect of Indigenous culture online. The difference

between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and

non-Aboriginal knowledge is summarised in Byrne

at al. (2008) and Christie (1994) and these

differences provide a model for general audio

sharing online as described in (Kutay & Ho, 2009).

The socialisation of learning to include Web 2.0

resources enables users to maintain update

information online. The learning is therefore focused

around collaboration in learning, as well as learning

knowledge developed collaboratively. In the

previous work we used a learning model for

dynamic creation of organisational knowledge and

compare this to the SECI model (Nonaka, 1994), in

particular looking at transforming tacit to explicit

knowledge. The design also provides a mapping

between technology and learning processes.

We extended the concepts developed in the

Indigenous mode of knowledge sharing to a model

that supports mainstream organisational learning.

For instance our approach is mirrored in research

into organisational learning where annotation tools

are enhanced using a user-centric approach that

includes the knowledge status of the annotator

(Ballim et al., 2004).

TrustOnlineforInformationSharing

217

4 PROTOCOLS

Aboriginal Australian story telling is a communal

form of oral history designed for the inheritance

structure of a society with minimal hierarchical. The

narrative that Aboriginal people maintained uses

group story telling process to select the stories that

are valuable and worth repeating, those that have

meaning for them. This is comparable to the social

constructivist learning process described by Berger

and Luckmann (1996).

The research into the usability of existing web

services and redesigning these for Indigenous

communities has been hampered by the irrelevance

of much online material, computer illiteracy and

lack of trust in the medium (Dyson and Leggett

2006); (Kutay, 2010). People are wary that their

knowledge will be used inappropriately, out of

context or separated from the community narrative

(Nakata and Langton, 2005); (Kutay, 2011). This is

compounded by what is seen as insufficient

government protection and lack of community

control (Janke, 1999). For indigenous people to

utilise the internet, issues of relevancy and usability

must be considered while developing trust in terms

of security of access and ensuring the material

remains in the context selected for it, and retaining

the scope and flexibility of cloud computing where

possible.

Research at The University of New South Wales

is developing web services to provide:

Access control system that links to ownership of

artefacts and mourning protocols

XrML description to manage access control of

files based on kinship

Collaborative annotation tool that incorporates

access protocol and reuse for learning

The data access control is to enforce protocol

through reference to a distributed database on

genealogy and kinship responsibilities. This requires

secure tools to write new or changed protocol

structures for mainstream multimedia sharing sites.

In general the use of protocols or policies to

enhance the flexibility of online learning is worth

investigation, as is the specific features that apply to

Aboriginal knowledge sharing (Kutay, 2009). The

provision of the web services focuses on options to

embed access protocols in distributed web services

(Wang et al., 2009) and autonomous information

sharing (Skogsrud et al., 2009). Also there is a need

to extend trust to cloud service provision with

distributed authorization control (Varandharanjan,

2005) to securely display culturally restricted

material on public sharing web sites.

5 EXEMPLAR

The new technology of our age is the sharing of

information electronically across the globe. It is

important that Aboriginal people involved in this

development. Also we should note that recent

learning theories stress that learning does not

necessarily translate solely into knowledge gains:

rather it can be measured in terms of increased

participation and interaction of individual with their

group or community in knowledge development. It

is the support and analysis of online interaction and

sharing of information that we use here as an

example of Indigenous knowledge sharing.

When government workers and community

organisations met to discuss the options for

information sharing online, the School of Computer

Science and Engineering (UNSW) offered support.

We worked together to find web services with

suitable social support that will provide an

environment in which the Aboriginal people can,

with confidence and ease, share their resources.

A combined meeting set up the requirements for

the web site, however the network is divided into a

growing number of separate regions around Sydney,

each servicing the Aboriginal community in their

region, and each with different information to share.

The site that was developed has been running for

over 4 years and we felt it was time to report on

what was, and was not, a success in this work.

5.1 Requirements Gathering

The Information site was set up as a content

management system framework and a wrapper to

various services. While other systems have been

developed focusing on annotation and sharing

(Saraiva and da Silva, 2009); (Chakravarthy et al.,

2006); (Schroeter et al., 2003) this work extends to

the management of information in many forms

(email, calendar events, pamphlets and photos) and

linking into more social media. (cf. Lavoué, 2011).

While previous work has suggested audio-visual

support useful, the people using the system did not

have access to audio or video equipment such as

web-cam and often did not have speakers on their

work computers.

While providing common services to all sub-

regions, there was a need to provide customisation

and extend components according to local needs.

The generic components of the system requested by

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

218

the different network meetings included separate

website access for each network region in Sydney

to:

Regional maps showing services in area

Directory of services and service types in area to

locate on map

Online email service to reduce download and

repeated forwarding of emails

Moderated email system that allow emails to be

moved across various topics and regions

Daily digest mail available to subscribed emails

Website email form as well as standard email

access to mail service

Document storage to link as attachment to emails

Calendar of events linked to email notification to

regional coordinators

Support for coordinators and representatives in

the use of the site.

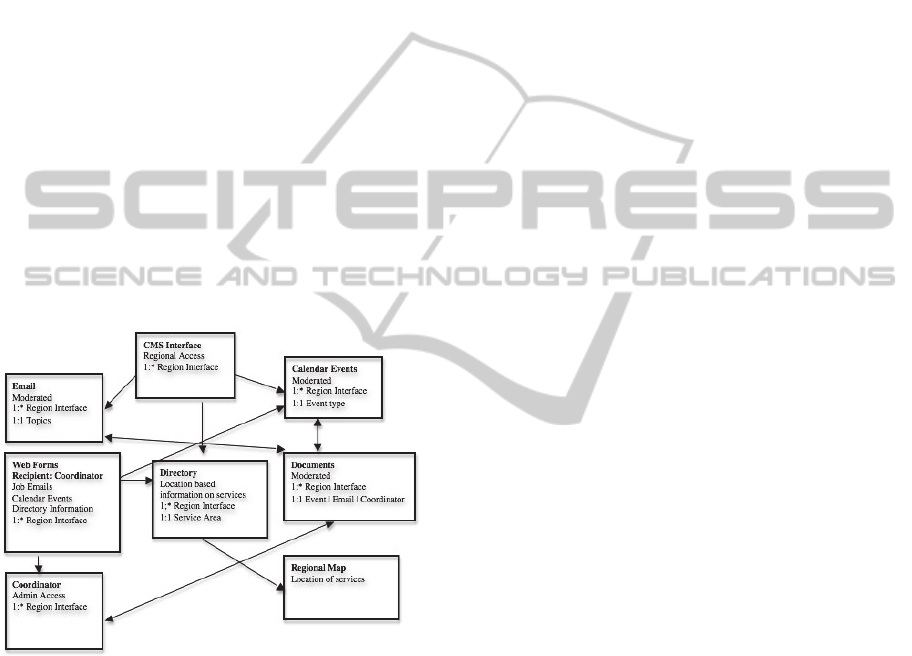

5.2 Architecture

The architecture is designed around the original

Sydney regional website with a configuration file

that was altered for each region. All features were

set up on the main regional website and then each

region could access their local component. This was

so that organisations that spanned many regions can

have access from one interface, while local users

could filter out other regions.

Trust

For Aboriginal users the issue of trust online has

revolved around (Kutay, 2011):

Misuse of information generated by Aboriginal

people, by non-Aboriginal people

Being identified as Aboriginal and hence being

abused

Information that should be private at certain

times (eg mourning) being shared publically

Aboriginal people want their services controlled

by Aboriginal people to ensure such protocols will

be followed

Information that ‘belongs’ to one person being

shared by another as an authority

It is perhaps the last point that has little analogy in

mainstream information sharing, however we will

briefly explain the others first.

The information on the site cannot be easily

linked through other services, so users feel this

remains in the context they intended for it, for

example the calendar events (see Access below). We

have used moderation to reduce the abuse of the site,

but still require users to add contact details, such as

email, for further information. This also provides the

users with acknowledgement of the ownership of

information.

The site has remained relatively free of spam and

abuse. Probably due to the small network actually

interested in the service and the open nature of the

site, there has been no attempt to hack or access the

site. This has increased the trust in the site, and the

interest in using the web for more services. Also

having control of the site content, and being able to

enforce protocols such as respect for ownership of

information, has empowered those coordinators who

have been involved and they are proud of the service

they provide.

The ownership of knowledge also provides a

way of determining the authority of the material. As

in the case of language, people will know who

submitted the information and will value it in that

light. While the coordinators have prio respect in the

community, they have become an authority through

their position in the online community. However,

while coordinators regularly change when a new

person moves into a more central node role in the

network, those no longer in that role would not

consider interfering or taking control as it is not their

responsibility anymore.

Access

The site provides some feeds but the calendar is not

compatible with other technologies to achieve this.

Cloud services such as Google calendar now exist,

but do not offer the privacy and the ability to tailor

the interface and the functionality to the network’s

requirements. Our research looks at new formats of

access control to cloud services and this is a case in

point.

The region selected by a user limits the events

shown, while events can be added to all regions,

hence the user as well as the original contributors

filter information.

Language

The language of the site is in Aboriginal English.

Contributions by those from various sections of

Australian culture are very different in form. It has

been suggested by some coordinators that the

language (as much as the author) provides a filter for

how much credence or relevance to accredit an

information piece. According to some it is not that

the language of such contributions is less familiar; it

is just that the language is used to discuss less

relevant material.

Immersion

The site has failed to keep up its interface to date,

due to lack of development funding. We are now

TrustOnlineforInformationSharing

219

seeking resources and support to upgrade to a new

look and feel that has a more ‘modern’ appeal. The

initial site was very basic template due to costs, but

this can be made to look more ‘smooth and elegant’

with minimal work. Also the lack of the Aboriginal

colours (red, black and yellow) on the site, a

decision of the original coordinators, is now

considered to have adversely affected access.

Otherwise the gradual construction of the site

through addition of new features every year or so

has keep the interface simple, and the basic CMS

construction has simplified navigation.

Relevance

The coordinators were very wary at first of adding

too much to the web site, as it would lose its focus

and its usefulness. They wanted the users to become

more familiar with the service before they expanded

it, and the have a feeling of control and ownership as

it grew.

The material is also moderated for relevance to

the site. It does not deal with political events or

specific immediate family events and issues, only

information that is relevant to the community.

Figure 1: Interface components.

5.3 Organisation

At present the site forms a fairly diverse collection

of information, as the network is very broad in

focus. There is little work we can do to tie the

various strands together in a more coherent form of

information sharing. However we can allow viewing

one piece of information through different interfaces

or formats.

Interoperability

Various services have multiple interfaces, or are

accessed by many services, so the interoperability of

the components for the site was always an issue.

Also the site was reliant on the contributions of the

novice public while completely moderated. Also the

separate sites are moderated by separate

coordinators, so overarching policy has to be

developed as issues arise.

Documents: The document repository needs to

support the storage of email attachments, details on

events and material shared by the network members.

At present the attachments have to be manually

stripped from emails and saved, but we are

researching how this step can be automated.

Events: The events are placed on a region’s

calendar, and can be also included in the regional

calendar. A publically added event will trigger an

email to the coordinator. Documents can be

uploaded to provide more information on events.

Emails: The emails are stored in a private

mailbox online. Coordinators can select to move

them to a public mailbox or delete them. Also a

daily digest is generated and emailed out on a

mailman list.

Forms: The site provides forms to guide users to

supply all the required information in an email to the

jobs vacant list. The lack of subjects on all emails

sent to the coordinators remains an issue.

Functionality

The users are generally novice, but also they

consider they are doing this information sharing as a

part of their work, while the government or

community sector that employs them does not

usually recognise this. Hence their time available to

upload or moderate material is limited. The usability

of the site had to be well developed as each new

service was added to reduce the load the extra

information source could cause.

For instance if an event is added, any pamphlet

relating to that event has to be linkable to the

calendar event. Also the service information in the

directory includes location data (which can be

entered through a Google map pin) to link to the

front map.

5.4 Protocols

The main protocols are developed in the face-to-face

meetings of the network, then enacted online

through the coordinators’ moderation and the users

choice of topics for submission. The coordinators

provide the elders, those most experience with web

communication or the most central in the local

network structure, and hence those most aware of

the local issues and interests. They set up the topics

relevant to their region.

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

220

We have not developed a blog or forum on these

sites. This level of interchanges is not considered

relevant as the site is purely for information sharing,

not for discussion and debate. This enables the site

to cater to a broader range of people, without

alienating any view.

All information is already public before it goes

on the site. It is not a site to provide private

information to the public arena. It is information that

is commonly held in one part of the community, and

gives them an opportunity to share it with others in

the community. This reduces the need to attribute

and protect material, and allows the users to become

more familiar with the tools in what is a familiar

communication format.

5.5 Issues

The main concern with the site was initially

developing trust of the service. The users were not

familiar with the Internet, and not aware of the

advances in web services over the last ten years in

the form of Web 2.0 that provided them an informal

but secure means of contributing to online

information. Learning this required being involved

with these Internet services.

The second issue was the interface. While the

community and government workers expressed

concern with the ‘usability’ of the site, the main

factor seemed to be the look of the site, if it was

modern in format. At the same time the issue of

usability related to general computer literacy in the

community, which is low, as well as the restrictions

on computer access at work in many government

organisations. For instance, we had to get permission

to access an online email service, and most workers

could not use Facebook or other social media that

would have improved interaction on the site.

As the site progressed the concern was mainly

with the interoperability of the site. Especially the

documents section played many roles, as repository

for email attachments, brochures for calendar events,

and photo sharing for Joint Network events.

This problem will only increase as we now move

to provide access for the users through social media.

In eLearning, it is acknowledged that social

interaction is a motivational form of knowledge

sharing (Kay et al., 2007). In sharing community

information and encouraging engagement in this

sharing there is a need to link to social media, as this

is the area which Aboriginal people can practise

more familiar and informal forms of information

sharing (Smith et al., 2000). The need to integrate

social networks with serious information sharing

systems requires ontological and web services

support (see Deparis et al., 2011), and to provide an

area the users trust within these.

5.6 Feedback

The main response to the web site is the great

reduction in emails. Given that the community is

close knit, there is a tendency for people to forward

emails to their lists, often including the sender. The

coordinators are usually a central node in the local

networks and so repeatedly received their emails.

The other area that is highly popular is the

publically editable calendar for social events such as

the annual Aboriginal week of celebrations.

However it would be good to have this linked into

other calendar services, such as computer based

services. The existence of different calendar services

is clearly an issue, but their compatibility is

increasing and the next upgrade will be to focus on

providing easier options to upload and download

events.

Also importantly the site provides one of the

main services outside Facebook that is regularly

used by Indigenous people in Sydney. It provides an

in depth and versatile form of information sharing.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The network service is not a particularly innovative

system, but the collaborative effort involved in its

design and the ongoing link with the community

through its development provides an interesting

view into information sharing in the Aboriginal

community. The joint network meeting regularly

provide feedback on the site and continually

suggests upgrades. We are indebted to these

coordinators for their ongoing commitment to

making the site an area they feel comfortable sharing

information with their peers. We also acknowledge

that their feedback has provided the source material

for our analysis of how and why the site has

developed in the format it did.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to acknowledge three

members of the Sydney Koori Interagency who

instigated this project and who donated much of

their time in the design and training for this system:

Lisa Murphy, Robert Leslie and Cassie Jackson.

TrustOnlineforInformationSharing

221

REFERENCES

Ballim, A., Fatemi, N., Ghorbel, H. and Pallotta, V., 2004.

A knowledge-based approach to semi-automatic

annotation of multimedia documents via user

adaptation. In Computing and Computers.

Berger, P. L. and Luckmann, T., 1966. The Social

Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of

Knowledge, Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Byrne, A., Gibson, J., Gardiner, G., McKeough, J.,

Nakata, M. and Nakata, V., 2008. Australian

Indigenous Digital Collections: First generation

issues. http://hdl.handle.net/2100/631.

Chakravarthy, A., Ciravegna, F. and Lanfranchi, V., 2006.

AKTiveMedia: Cross-media Document Annotation

and Enrichment. In Proceedings Fifteenth

International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC2006)

Christie, M., 1994. Grounded and Ex-centric Knowledges:

Exploring Aboriginal Alternatives to Western

Thinking in John Edwards (Ed) Thinking:

International Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Victoria:

Hawker Brownlow Education.

Dyson, L. and Leggett, M., 2006. Towards a Metadesign

Approach for Building Indigenous Multimedia

Cultural Archives. Proceedings of the 12th ANZSYS

conference – Sustaining our social and natural capital.

Katoomba, NSW Australia, 3–6 December

Janke, T., 1999. Our Culture: Our Future. Report on

Australian Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual

Property Rights commissioned by AIATSIS and

ATSIC.

Kay, J., Reimann P., and Yicef K., 2007. Mirroring of

Group Activity to Support Learning as Participation.

In R. Luckin et al. (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence in

Education IOS Press.

Kutay, C., 2011. HCI study for Culturally useful

Knowledge Sharing, In 1st International Symposium

on Knowledge Management & E-Learning (KMEL).

Kutay, C., 2010. Issues for Australian Indigenous Culture

Online. In E. Blanchard, D Allard (Eds.) Handbook of

Research on Culturally-Aware Information

Technology: Perspectives and Models. IGI Global.

Kutay, C. and Ho, P., 2009. Australian Aboriginal

Protocol for Modelling Knowledge Sharing. In

Proceedings of IADIS International Conference on

Applied Computing Rome, Italy.

Lavoué E., 2011. A Knowledge Management System and

Social Networking Service to Connect Communities

of Practice. In Fred A., Dietz J. L. G., Liu K., Filipe J.

(Eds.) Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering

and Knowledge Management, pp. 310-322

Nakata, M. and Langton, L., Eds 2007. Libraries and

Indigenous Knowledge: A National Forum for

Libraries, Archives and Information Services.

http://hdl.handle.net/2100/57

Nonaka, I., 1994. A Dynamic Theory of Organisational

Knowledge Creation, Organisation Science, 5,1,

pp.14-37.

Mellor, D., 2001. Artefacts of Memory: Oral histories in

archival institutions. In Humanities Research, III,1.

Pirolli, P. & Card, S., 1997. The evolutionary ecology of

information foraging. Technical Report, UIR-R97-0l.

Palo Alto, CA: Xerox PARCo.

Rogers, Y. and Scaife, M., 1998. How can interactive

multimedia facilitate learning? In J. Lee, (Ed.)

Intelligence and multi modality in multimedia

interfaces: Research and applications, pp. 68-89.

Rosenzweig, R. and Thelen, D., 1998. The Presence of the

Past, Popular Uses of History in America, New York,

Columbia University Press.

Saraiva, J. and da Silva, A., 2009. WebC-Docs: A CMS-

based Document Management System". In

Proceedings of the International Conference on

Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

(KMIS), INSTICC.

Schroeter, R., Hunter, J. and Kosovic, D., 2003. Vannotea:

A collaborative video indexing, annotation and

discussion system for broadband networks. In S.

Handschuh, M. Koivunen, R. Dieng and S. Staab,

Proceedings of the Second International Conference

on Knowledge Capture: K-Cap 2003. pp. 23-26.

Skogsrud, H., Motahari-Nezhad, H. R., Benatalla, B. and

Casati, F., 2009. Modeling Trust Negotiation for Web

Services, Computer, 42, 2: pp. 54-61.

Smith, C., Burke, H. and Ward, G., 2000. Globalisation

and Indigenous People: Threat or Empowerment? In

C. Smith and G. Ward (Eds.) Indigenous Cultures in

an Interconnected World

Varadharajan, V., 2005. Authorization and Trust

Enhanced Security for Distributed Applications. In

Information Systems Security. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, pp.1-20

Wang, K-J. Lin, D. S. Wong and V. Varadharajan, 2009.

Trust Management Towards Service-Oriented

Applications. In Service Oriented Computing and

Applications Journal (SOCA), Springer, 3, 2.

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

222