Homeostasis

The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models

Gil Regev

1,2

, Olivier Hayard

2

and Alain Wegmann

1

1

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), School of Com-puter and Communication Sciences,

CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

2

Itecor, Av. Paul Cérésole 24, cp 568, CH-1800 Vevey 1, Switzerland

{gil.regev, alain.wegmann}@epfl.ch, {g.regev, o.hayard}@itecor.com

Keywords: Business Modelling, Survival, Systems, Identity, Homeostasis, Entropy, Negentropy.

Abstract: Business modelling methods most often model an organization’s value provision to its customers followed

by the activities and structure necessary to deliver this value. These activities and structure are seen as

infinitely malleable; they can be specified and engineered at will. This is hardly in line with what even

laymen can observe of organizations, that they are not easy to change and that their behaviour often is not

directly centred on providing value to customers. We propose an alternative view in which organizations

exist by maintaining stable states that correspond to their identity. We analyse how these states are

maintained through homeostasis, the maintenance of ones identity. Homeostasis helps to explain both the

inability of organizations to provide maximum value to their customers and their reluctance to change. From

this point of view, resistance to change is not something to fight or to ignore but an essential force behind

organizational behaviour that can be built upon for creating adequate strategies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business modelling refers to the description of

organizations for the purpose of understanding their

informational needs. The premise of business

modelling is that IT needs to support the

organization and it is therefore crucial to fully

understand it (Shishkov, 2011). Business modelling

often begins by modelling the business processes of

the organization and proceeds down the hierarchy to

the way these processes are supported by the IT. In

this view, a business model is a description, as

complete as possible, of some part of the

organization that needs IT support.

Business modelling also refers to the modelling

of organizational strategy through initiatives such as

Service Science (Spohrer and Riecken, 2006) and

frameworks such as e

3

value (Gordijn and

Akkermans, 2003) and the Business Model

Ontology (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). A

business model in these later frameworks describes

how a company provides and captures value

(Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). In this paper, we

will refer to business modelling as the description of

the complete organization, including its business

strategy.

The strategy formulation of business modelling

seems to be the direct product of the two leading

schools of strategic thinking (Design and

positioning) as viewed by Mintzberg et al. (1998).

Just like the methods inherited from these three

schools, business modelling dissociates strategy

formulation from implementation. Implementation,

it seems, is straightforward. If the strategists can

define winning business models, the company can

surely implement them. Also, strategic business

modelling considers that organizations exist by

maximizing value to customers and capturing part of

this value. This view glosses over the everyday

observation that organizations define their own rules

that they consider good enough for their customers.

Maximizing value for customers is not apparent in

even the most successful commercial companies.

When describing the operational part of Business

modelling, the models mostly contain roles

processes, business rules, IT systems etc. There is no

description of the mechanisms that maintain the

organization in place. Business modelling does not

address questions such as how come the

organization exists and what is its capacity for

change. Business modelling is all about change in

the way the organization does business today. If

13

Regev G., Hayard O. and Wegmann A.

Homeostasis - The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models.

DOI: 10.5220/0004460700130023

In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2012), pages 13-23

ISBN: 978-989-8565-26-6

Copyright

c

2012 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

there were no need to change, it would mean that

whatever the organization is doing right now is

working and therefore there is no need for a new

business model. Implementing a new business model

is not an easy change and in most organizations it

either fails or is accompanied by years of upheaval.

Or as Michael Hammer, who coined the term

Business Process Reengineering (BPR) in the late

1980s, has subsequently said reengineering

transformed (Hammer, 1996): “organizations to the

point where they were scarcely recognizable.” or in

other words “it saved companies by destroying

them.”

This is because most of the times companies, just

like any organization survive not through radical

change but by closely controlling change.

In this paper, we take the challenge of explaining

an essential ingredient of organizational survival

called homeostasis. Homeostasis was developed in

the field of Physiology by Walter Cannon (Weinberg

and Weinberg, 1988) but has such a broad

description that it readily useful for describing the

way organizations survive in a changing

environment. Homeostasis, at its core, is a struggle

against change. It therefore provides a good basis for

explaining why new business models often fail.

Because it is at the core of what the organization is,

taking it into consideration will create much more

accurate business models.

In Section 2 we give a few examples drawn from

everyday life and from published cases, such as

Apple, to show the problem of strategy,

organizational culture and customer value. In

Section 3 we provide an overview of business

modelling. In Section 4 we explain the fundamentals

of maintaining identity and negative entropy. In

section 5 we explain the concept of Homeostasis. In

Section 6 we describe the practical aspects of

thinking in terms of Homeostasis.

2 A FEW BUSINESS EXAMPLES

Whereas the focus of business modelling is to

understand what value the business provides to its

customers and how it provides it, there are many

examples where this value is not readily apparent.

These examples do not belong to failed companies

but to all existing companies. We provide a few

examples to illustrate this point.

Apple’s Strategic Constancy

Apple is in the enviable position of having created a

host of products and services that customers find

very valuable, which allows it to charge a premium

price.

But, as much as competitors try to imitate

Apple’s business model, they are often unable to

replicate the same products and services. This, we

believe, is explained by Katzenbach (2012) as Jobs

ability in understanding the role of culture in

sustained strategic capabilities. Jobs, Isaacson

(2011) says, was interested mostly in creating “an

enduring company.” It is more difficult to create an

enduring company entrenched in culture than to

create business models that imitate Apple’s.

However, without the culture, the business models

have little chance of succeeding, as can be seen in

HP’s recent experience with the TouchPad.

Apple’s endurance can be seen in many aspects

of its culture. For example, the three principles that

to this day guide Apple’s Marketing Philosophy

were written at its very beginning by Mike Markkula

who was brought in by Steve Jobs (Isaacson, 2011),

These three principles are (Isaacson, 2011): (a)

Understanding customer needs better than other

companies by establishing an intimate relationship

with their feelings. (b) Focus on what is important

and eliminating what is not. (c) Presenting Apple’s

products professionally and creatively. Isaacson

(2011) says that these principles shaped Jobs’s

approach to business ever since.

After he was ousted from the company in 1985,

these three principles held on for a while but slowly

fizzled with Apple producing an ever-larger number

of products with lower appeal to customers and less

attention to their presentation and packaging.

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he

recreated its culture by various measures, such as

(Isaacson, 2011): bringing back previous employees,

creating incentives for keeping trusted employees,

replacing Apple’s board, and removing all projects

that he estimated as not focused.

The quality Jobs built into the iMac, MacBook,

iPod, iPhone and iPad is in a direct line with the

quality he built into the original Macintosh. Like the

original Macintosh, all these products are physical

sealed so that only Apple can open them. In most of

these products, customers cannot even replace the

batteries. Replacing batteries in Notebooks, MP3

players and smartphones is a standard and highly

valuable feature, as batteries tend to fail with time.

An iPhone with a dead battery can only be returned

to the Apple for replacement, at a much higher cost

and delay than it would be for replacing a battery in

a Nokia smartphone. An evaluation of customers’

desires, will most probably list the simple and low

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

14

cost change of battery as a very valuable feature.

However, this is purposefully missing from Apple’s

products.

Steve Jobs maintained a remarkable constancy in

the kind of products he envisioned. According to

Isaacson (2011) as way back as the early Macintosh

days he wanted to design more curvy, colourful and

friendly looking computers. Although the first

Macintosh was a good start, the really curvaceous

and colourful computers appeared with the iMac

some 15 years later. Whereas during his absence

Apple designed more and more common looking

computers, when Jobs took over in 1997 he re-

established the design philosophy he began in the

1970s.

As strange as it may sound today, Jobs was

reluctant to allow third party developers to create

apps for the iPhone for fear of compromising its

security and integrity (Isaacson, 2001). Only when

he found a way to bring together both aspects of

opening the iPhone to external developers while

maintaining strict control over what they provided,

did Jobs accept to change his opinion. The result

was the famous Apple Store, which today provides

great value to customers as well as to Apple and to

developers.

A Motorcycle Manufacturer

In (Hopwood, 2002) Hopwood describes a project in

a motorcycle manufacturer in the 1930s where

engineering produced a magnificent motorcycle, far

superior to competition but management was

unwilling to invest in the new tooling that was

required to produce it. The changes made to produce

the motorcycle with the old tooling made it too

heavy and inferior to competitors. Why would

management act in such a way? Is it simply

insensitivity or is it that there’s something else to say

about resistance to change?

Maintaining a Revenue Stream

A recent article in the New York Times (Chozick,

2012) describes attempts by General Motors to

maintain its appeal for youngsters. Apparently,

present day youngsters are less interested in owning

a car than previous generations. GM is trying to

compensate for this lack of interest by hiring MTV.

A dramatic cultural change is needed for GM to be

able to carry out the changes that MTV deems

necessary. GM does not seem to be primarily

concerned by the value it provides to these new

customers but by insuring its own revenue stream in

the medium to long-term future.

Prices of periodical subscription by for

individuals and libraries have increased even though

printing cost has largely disappeared. Where is the

value for the customer? At the same time, “new”

schemes such as borrowing ebooks are appearing

even though the borrowing of books was invented

because books were a scarce resource whereas

ebooks can be reproduced ad-infinitum. Again, the

value for the customer is unclear.

On-line Retailers

Many companies’ websites terms of use, e.g.

Apple’s iTunes, explicitly state that they make no

promise that their website contents will be error-

free, that they will offer continuous service and the

like. Apple even goes as far as saying that the sole

remedy available to dissatisfied customers is to stop

using their website.

On-Line retailers have strict policies applied to

customers who want to return products. These rules

vary with the location of the company. In

Switzerland, for example, the rules are often much

more strict than in the United States. These policies

embody legal and cultural aspects of the company

and of the country and region concerned. Return

Merchandise Authorizations (RMA) are sometime

imposed by retailers. International sales are

frequently subject to stricter rules and exclusions

than domestic sales. The value for the customer is

not apparent in these policies.

Even Amazon.com that prides itself on its

superior customer service cannot avoid having some

rules concerning the return policies governing items

purchased by customers. These rules exclude the

returns of some items and defines what can be

returned and it what state. Returns are accepted

within 30 days, for example, but why 30 days? Why

not 90 or 10? Why is there a limit at all? The return

policy also excludes returns for items bought

through the CDNOW Preferred Buyer’s Club. Why

are these items excluded? Also music items must be

unopened for the return to be accepted whereas

books do not. Why is this?

A Healthcare Insurance

All Swiss residents are obliged by law to have health

insurance, which they pay for themselves. Health

insurance premiums for a family of four )2 adults

and two children under 18 years old) is about 1000

Swiss Francs for a standard plan with the lowest co-

Homeostasis - The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models

15

payment. The premiums have increased regularly

every year for the last 10 to 15 years. Switching

from one insurer to another is possible once a year.

Many Swiss residents try to switch to the insurer that

offers the lowest cost each year. In 2010 one of the

smaller insurers was at the top of the list of the least

expensive insurers. This insurer also had a very good

reputation for quality. The result was a massive flow

of new customers to this insurer. About 18 months

later many new customers received a surprising and

important premium hike, some of more than 60%,

making this insurer the most expensive. Thus, this

insurer went from the least expensive to the most

expensive. This new pricing scheme will probably

result in a massive drain of customers to other

insurers. This price increase makes no sense if the

goal of the insurer, as enterprise modelling methods

consider, is to attract more customers.

3 AN OVERVIEW OF BUSINESS

MODELING

Business modelling, enterprise modelling, enterprise

architecture and enterprise engineering are used

somewhat interchangeably to mean models of how

an organization functions. Business modelling has

emerged from the Information Technology (IT)

practice as a way for IT people to understand the

business’s information needs. One of the early IT

frameworks that integrate some aspects of business

is what came to be called the Enterprise Architecture

Framework, the Information Systems Architecture

Framework, or more commonly the Zachman

Framework (Zachman, 1987). Zachman’s

framework is made of a matrix in which the rows

represent entities and the columns represent

questions about these entities (e.g., what, how,

when, why, where). The two topmost rows of

Zachman’s matrix represent the entities that are

important to the business, the actions (processes)

that are important, and the business locations.

Sowa and Zachman define a business model as

(1992): the “design of the business” that shows “the

business entities and processes and how they

interact.” From the architecture perspective inherent

in this framework, a business model is seen as

(Sowa and Zachman 1992): “the architect’s

drawings that depict the final building from the

perspective of the owner, who will have to live with

it in the daily routines of business.”

The Reference Model of Open Distributed

Processing is an ISO/IEC standard for describing

organizations, their informational needs and their IT

support (ISO/IEC, 1995-98). It consists of five

viewpoints on the business: Enterprise, information,

computational, engineering and technology (Kilov,

1999). The enterprise viewpoint captures the

purpose, scope and policies of the organization

(Kilov, 1999).

ArchiMate is a more recent enterprise

architecture method, which models business

processes and their support by IT. ArchiMate

defines business systems as dynamic systems. A

dynamic system is described by active structure

concepts (also called agents), passive structure

concepts (also called patiens) and behavioural

concepts (Lankhorst et al., 2009). ArchiMate is

made of three layers called Business, Application

and Technology (Lankhorst et al., 2009). The

business layer describes business actors and roles

performing business processes that deliver products

and services to external customers. The application

layer describes the support provided by software

applications to the business layer. The technology

level describes the infrastructure necessary to run the

software applications (Lankhorst et al., 2009).

The Design & Engineering Methodology for

Organizations (DEMO) is a methodology for

literally engineer organizations (Dietz, 2006).

Organizations are said to be “designed and

engineered artifacts” much like cars and IT systems

but with the exception that their “active elements are

human beings in their role of social individual or

subject.” (Dietz, 2006). In DEMO the essence of the

enterprise are transactions consisting of production

acts and coordination acts between the subjects.

With production acts the subjects create the “goods

or services delivered too the environment.” With

coordination acts the subjects “subjects enter into

and comply with commitments toward each other

regarding performance of P-acts Examples of C- acts

are “request,” “promise,” and “decline.”” (Dietz,

2006).

The examples above are all methods that attempt

to model the organization with multiple viewpoints

and multiple levels, i.e. from business to IT. Other

business modelling methods address only the

strategic definition level. e

3

value focuses on the

exchange of value objects between economic actors

(Gordijn and Akkermans, 2003). The organization is

viewed only as a black box. e

3

value has been linked

with i*, a leading Goal Oriented Requirements

Engineering method (Gordijn and Yu, 2006). Value

and goal models are used to show the value activities

that contribute to the enterprise goals (Gordijn and

Yu, 2006).

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

16

The Business Model Ontology, BMO,

(Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010) provides multiple

ways of defining business models. Osterwalder and

Pigneur define the concept of business model as

(Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010): “the rationale of

how an organization creates, delivers and captures

value.” BMO proposes a canvas containing 9

elements: Customer Segments, Value Propositions,

Channels, Customer Relationships, Revenue

Streams, Key Resources, Key Activities, Key

Partnerships and Cost Structure (Osterwalder and

Pigneur, 2010). Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010)

describe a number of business model patterns and

show how they can described in the canvas. BMO

focuses on the strategy formulation level and doesn’t

have an architecture component. The execution of

the business model stops at the definition of the key

resources and partnerships. More recently, work is

underway (Fritscher 2011) to couple BMO and

ArchiMate in order to provide a more complete

business layer for ArchiMate and to more finely

define the execution of BMO business models.

Most business modelling frameworks assume

that the organization’s main purpose is to provide

value to the customer. Hammer, for example

(Hammer, 1996), asks the question “what is a

company? What is it for?” The answer according to

Hammer is that (Hammer, 1996): “a company exists

to create customer value. Everything a company

does must be directed to this end.” Hammer defines

a customer in quite unorthodox terms. Moving

beyond the notion of (Hammer, 1996) “someone

who buys what the company sells.” He defines a

customer as (Hammer, 1996): “people whose

behavior the company wishes to influence by

providing them with value.” Hammer considers as

customers a much larger set than is traditionally the

case. He gives the following list as customers of a

pharmaceutical company (Hammer, 1996):

A. “The patient

B. The physician

C. The pharmacist

D. The wholesaler

E. The Food and Drug Administration

F. The Insurance company”

Notice that some of these customers, most

notably, the physician, pharmacist and wholesaler

would often be seen as suppliers rather than

customers, whereas the Food and Drug

Administration would be seen as a regulator today.

Hammer’s point is that their behaviour needs to be

influenced by the company so that they are all

willing to do their part in the sale of the medicine

sold by the company. But the value expected by

each of these customers is not the homogenous. The

pharmacist expects a different value than the patient

and the insurance company. The Food and Drug

Administration is there to impose rules that constrain

the sale of the medicine.

For Hammer (Hammer, 1996): “All of a

company’s activities and energies must be focused

on and directed to the customer, who is, after all, the

source of the company’s revenue.” Hammer (1996)

explains why he puts customers as the sole and only

reason for existence of a company by arguing that

(a) shareholders also provide funds to the company

but employees of a company cannot be motivated by

the argument that they need to create more

shareholder value. (b) In a global economy,

customers have the upper hand over suppliers.

As we have seen in the various examples from

the business modelling literature, value creation for

customers is seen as the single most important

reason for a company’s existence. The resources,

activities, and structure of the company are

subservient to this all-encompassing goal.

With respect to the business examples we gave

in the previous section, we can formulate a few

critiques of this view.

If customers have the upper hand then why is it

that the supplier defines the sales conditions and not

the customer? Can an iPhone customer define the

iTunes store conditions, or Google’s privacy rules?

Inspecting sales conditions and contracts of all

kinds, shown in the previous section, we see that

they protect the supplier more than they protect the

customer. We are forced to conclude that companies

cannot really maximize the value proposed to any

individual customer, as proposed in business

modelling.

In business modelling, it is assumed that the

structure of the organization is defined once the

value proposition has been defined. In other words,

structure follows strategy. But structure, as

Mintzberg et al. put it (1998): “follows strategy like

the left foot follows the right” meaning that it is

structure that enables strategy and strategy that

changes the structure. Hence, without a firm

structure of some kind, no strategy is possible. But

where does structure comes from and how is it

maintained?

As we have seen, business modelling methods

mostly use abstractions such as roles, agents, actors,

processes, transactions, commitments, services and

value. These abstractions have been carefully

devised to be free of any real human element, which

rarely or ever appear in these models. However,

ultimately it is people and organizational

Homeostasis - The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models

17

departments that must execute the business models

and it is then that problems arise because they were

abstracted since the beginning.

4 MAINTAINING IDENTITY

Remember that Steve Jobs wanted to create an

enduring company, but what did he mean by the

term enduring? What is an enduring company? Let’s

take a few examples? Compaq existed for some 20

years, since1982 until its acquisition by HP in 2002.

During that time it could have been said to be an

enduring company, since nothing ultimately lasts

forever. But what made Compaq enduring and what

ended this endurance? We have shown elsewhere

that for an organization to exist, it needs to maintain

a number of norms (states that remain stable or

constant) for a set of observers (Regev and

Wegmann, 2004, Regev and Wegmann, 2005,

Regev et al., 2009, Regev et al., 2011, Regev and

Wegmann, 2011). Based on this model, Compaq

existed because it maintained a number of norms

that customers, shareholders, suppliers, employees,

competitors and others could see as identifying the

organization called Compaq. When Compaq was

acquired by HP most of its constituent elements, e.g.

people, buildings, machines and even website,

continued to exist but were not organized in a

coherent whole that observers could identify and call

Compaq. Instead, most of them were absorbed in a

new structure called HP with different relationships

giving them a different meaning for observers.

Drawing an analogy with biological phenomena,

we can say that a company that is being acquired by

another is quite similar to a mouse being eaten by a

cat. The mouse maintains somewhat independent

existence and as observers, we can identify it as a

mouse. If it is caught and eaten by a cat, none of its

constituent elements have disappeared, but the

relations that they had, which made a whole that we

could identify as a mouse, have been altered so that

we cannot see the mouse anymore.

Whether it is a company or a mouse, from this

general systems point of view, the process is the

same. An organized entity that can be identified as a

whole, having some integrity, is swallowed by

another and cannot be identified as this whole

anymore.

The concept of an open system explains the

threats and opportunities posed by the environment

to the organization (Regev and Wegmann, 2004,

Regev and Wegmann, 2005, Regev et al., 2009,

Regev et al., 2011, Regev and Wegmann, 2011). An

open system draws energy from its environment in

order to decrease its entropy. Negative entropy

(Negentropy) is a measure of order. In a world

governed by the second law of thermodynamics, any

closed system will move toward positive entropy,

i.e. disorder. To maintain order an open system

draws energy from its environment. In terms of our

discussion above, this means that organizations

exchange goods, services, ideas and money with

their environment in order to maintain their internal

relationships in specific states so that their

stakeholders identify them (Regev and Wegmann,

2004, Regev and Wegmann, 2005, Regev et al.,

2009, Regev et al., 2011, Regev and Wegmann,

2011). Organizations, therefore, must establish

relationships with other organizations (Regev and

Wegmann, 2004, Regev and Wegmann, 2005,

Regev et al., 2009, Regev et al., 2011, Regev and

Wegmann, 2011). These relationships, as we have

seen are necessary but also potentially harmful

(Regev et al., 2005). Compaq, for example, had to

have relationships with its competitors, which

opened the door for its acquisition by HP.

To endure, therefore, the organization as much

as the animal, must protect itself from threats to its

organized whole. Not all of these threats come in the

form of a cat or a buyout. The organization must

protect itself from many threats, most of which may

look benign (consider Amazon’s threat to Barnes

and Noble or Borders in 1995).

In the next section we explain Cannon’s heuristic

device, Homeostasis, which explains how this

protection is done.

5 HOMEOSTASIS

Homeostasis is a term coined by Walter Cannon, a

physiologist, to describe the way a human body and

other organized entities maintain constancy in a

changing world (Regev et al., 2005, Regev and

Wegmann, 2005, Weinberg and Weinberg, 1988).

Homeostasis literally means (Weinberg and

Weinberg, 1988): “remaining the same.”

Weinberg and Weinberg (1988) describe

Homeostasis as a heuristic device to think about how

states remain constant (i.e. how norms are

maintained). They provide the following quote from

Cannon (Weinberg and Weinberg, 1988):

Proposition I In an open system, such as our

bodies represent, compounded of unstable

material and subjected continually to disturbing

conditions, constancy is in itself evidence that

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

18

agencies are acting or ready to act, to maintain

this constancy [..]

Proposition II If a state remains steady it does

so because any tendency towards change is

automatically met by increased effectiveness of

the factor or factors which resist the change. [..]

Proposition III The regulating system which

determines a homeostatic state may comprise a

number of cooperating factors brought into

action at the same time or successively. [..]

Proposition IV When a factor is known which

can shift a homeostatic state in one direction it is

reasonable to look for automatic control of that

factor, or for a factor or factors having an

opposing effect. [..]

Note that Cannon speaks in very general terms,

he takes the example of a body but what he says can

be applied to any enduring organization. Hence,

Weinberg and Weinberg (1988) note that

homeostasis is a very general and useful heuristic

device.

Weinberg and Weinberg (1988), give colourful

names to Cannon’s proposition, arguing that they are

so important that they merit memorable names. They

identify 5 principles in Cannon’s four propositions.

The fourth proposition giving two distinct principles.

They thus call them pervasiveness, perversity, plait,

pilot and polarity principles.

The Pervasiveness principle is a general

statement that draws our attention to the fact that in

a changing environment, behind every constant state

there are mechanisms that act against change. It

refers to the ubiquity and never ending nature of

regulatory mechanisms. It reminds us that we need

to investigate how each entity we observe is

maintained constant.

The perversity principle tells us to look for

activities that maintain this constancy (Weinberg

and Weinberg, 1988). Not only should we look for

activities, but we should also expect increased

effectiveness of these activities when they oppose

change.

The plait principle tells us to look for multiple

mechanisms and not stop when we found only one

(Weinberg and Weinberg, 1988). A homeostatic

system brings together multiple mechanisms, each

having a specific state to maintain constant.

The pilot principle makes us look for an

automatic control of each mechanism (Weinberg and

Weinberg, 1988). This automatic control explains, in

part, why we often do not see homeostatic

mechanisms. When some state is controlled

automatically, by definition, no conscious control is

needed. Hence, most homeostatic mechanisms are

applied without us even being aware of them. They

have been internalized and made tacit (Vickers,

1987). Often, it is only when they fail that we

become conscious of them, as shown in (Winograd

and Flores, 1986).

The polarity principle makes us look for

mechanisms that have opposite effects from one

another (Weinberg and Weinberg, 1988). These are

mechanisms that counter the counter of change.

These opposing mechanisms can be quite confusing.

They act against each other in ways that often seem

to us to be at odds or to be inconsistent. Their

overall effect, however, is to ensure that the state

controlled by the homeostatic system does not stray

outside the tolerance level, or as Weinberg and

Weinberg (1988) call them, the “critical limits.”

A homeostatic system does not distinguish right

from wrong. It only maintains some state constant. It

doesn’t care whether maintaining this constancy is

good or bad. This is as true for a human body as it is

for an organization. Weinberg and Weinberg

describe this property of homeostatic systems as

(1988): “The same mechanisms that prevent us from

being poisoned also prevent us from being

medicated.” The “right” strategy that may be able to

save a company can be effectively diffused by

homeostasis. When conditions change and the

homeostatic system doesn’t, its reaction to change

may not be effective. Hence, it is up to an observer

to determine whether a given constancy is good or

bad, not for the homeostatic system itself.

What we often call learning, is a way to change

this constant state (Regev and Wegmann 2005). This

means that the homeostatic system needs to create

new mechanisms for maintaining this state constant.

The perversity and polarity principles create

inconsistency that is often judged by observers to be

a bad situation to be corrected but is merely what it

takes to maintain constancy.

Despite the complexity of a homeostatic system,

it may not always be successful. If all homeostatic

systems were always successful, nothing would ever

change and everything would last forever. Thus,

when some changes occur, the homeostatic system

will adapt to them and different mechanisms will be

produced to enforce a new constancy. This may

result in a new identity for one or more observers.

Because homeostasis is such a ubiquitous

phenomenon in enduring organizations and because

business modelling is ultimately concerned with

creating enduring organizations, homeostasis has a

very large applicability to business modelling, In the

Homeostasis - The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models

19

next se

c

used in

f

6 H

O

B

U

We beg

i

it mean

t

an orga

n

organiz

a

not nece

what is

system (

W

is not n

e

b

uilding

from th

e

b

e a m

e

Weinbe

r

some pr

o

is not a

b

inside o

f

1988) “

t

This in

t

environ

m

the orga

n

a homeo

The

sale, co

n

supplier

s

part of

h

inside o

f

b

e unst

a

organiz

a

“unstabl

e

disturbi

n

multiple

rules, as

Figu

r

c

tion we outl

f

uture busines

O

MEOST

A

U

SINESS

M

i

n by asking t

h

t

o be part of

a

n

ization. Wh

a

a

tional model,

e

ssarily what

i

subject to th

e

Weinberg an

d

e

cessarily phy

s

and even if

e

given buildi

n

e

mber of a

r

g (1988) e

x

o

tection fro

m

b

solute. It si

m

f

the organiz

a

t

o come into

t

urn means t

h

m

ent will not

n

ization. Phy

s

static protect

i

business rul

e

n

tracts etc. th

a

s

, members

a

h

omeostasis.

T

f

the organiz

a

a

ble relation

s

a

tion. Reme

m

e

material

a

n

g conditions.

mechanisms

specified by

C

r

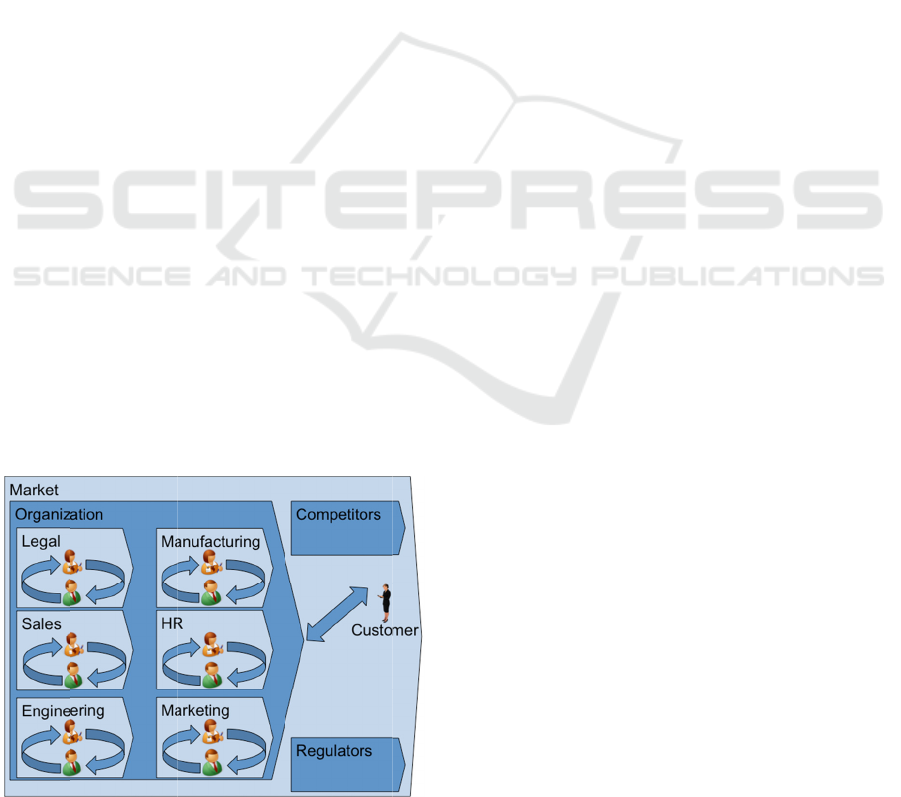

e 1: What ma

k

ine some as

p

s modelling

m

A

SIS FO

R

M

ODELI

N

h

e basic que

s

a

n organizati

o

a

t we put ins

i

such as the

o

i

s physically

c

e

protection

o

d

Weinberg,

1

s

ically contai

n

it is its peo

p

n

g. What do

e

company?

A

x

plain, it me

m

some threat

s

m

ply makes i

t

a

tion (Weinb

e

equilibrium

w

h

at signals o

r

be easily t

r

a

n

s

ical contain

m

i

on.

e

s, terms of

u

a

t organizatio

n

a

nd custome

r

T

hey are desi

g

a

tion from w

h

s

hips inside

m

ber that

C

a

nd subjecte

d

” Enduring o

in place in

C

annon’s pro

p

k

es these relatio

n

p

ects that ca

n

m

ethods.

R

N

G

tion of what

d

o

n, or to be i

n

i

de the box

o

o

ne in Figure

c

ontained in i

t

o

f its homeos

988). A com

p

n

ed in one ar

e

p

le come an

d

e

s it mean th

e

A

s Weinberg

ans

b

eing u

n

s

. This prote

c

less easy fo

r

rg and Wein

b

w

ith the exter

i

r

stimuli fro

m

n

smitted to w

i

m

ent is also o

f

u

se, conditio

n

n

s impose on

t

r

s are the vi

s

g

ned to protec

t

h

at it conside

r

and outside

annon refer

s

d

continuall

y

rganizations

h

to enforce t

h

p

ositions.

n

ships durable

?

n

be

d

oes

n

side

o

f an

1, is

t

but

s

tatic

p

any

e

a or

d

go

e

n to

and

u

nder

c

tion

r

the

b

erg,

i

or.”

m

the

i

thin

f

fers

n

s of

t

heir

s

ible

t the

r

s to

the

s

to

y

to

h

ave

h

ese

?

ent

i

ho

m

as

k

org

exi

s

a

h

exi

s

b

u

s

tha

t

its

org

out

Ar

c

sit

u

wa

n

use

ch

a

org

wa

y

M

o

use

ex

p

it

d

to

m

co

m

of

t

ho

m

ho

m

str

a

str

a

for

t

Ap

p

re

m

ho

m

re

m

rea

c

Ap

p

im

p

b

e

fo

tha

t

iPa

d

ori

g

int

e

att

e

ha

p

b

ei

n

Ap

p

acc

res

e

hal

t

These mech

a

i

ties within t

h

m

eostatic sys

t

what make

s

anization l

e

s

tence, what

m

h

euristic de

v

s

tence, we c

s

iness model

h

t

keeps it ali

v

activities wi

l

anization’s

n

s

ide the org

a

c

hitecture m

e

u

ation but a

n

t our model

s

ful to model

t

Business m

o

a

nge in mi

n

anization as

i

y

we want it

t

o

delling the

ful in both c

a

p

lain what ma

k

urable. For t

h

m

ake it durab

l

When creat

i

m

pany. We n

e

t

he company

a

m

eostasis.

T

m

eostasis ca

n

a

tegy or def

e

a

tegy fits the

s

t

unate that so

m

p

le pre 1985

m

oving projec

m

eostatic me

c

m

iniscent of 1

c

tion becaus

e

p

le was sub

j

p

osed the sa

m

fo

re, albeit wi

t

t

the new

A

d

) share som

e

g

inal 1984 M

a

e

grated hard

w

e

ntion to de

s

p

pened by ch

a

n

g imposed

o

p

le, Apple

epted expa

n

e

mbled IBM

t

when Jobs’s

The homeo

s

a

nisms will

b

h

e organizatio

n

t

em. Referrin

g

s

each of t

h

e

ad a so

m

m

akes it dura

b

v

ice for und

e

a

n presume

h

as some sort

e. This, in tu

r

l

l not be ali

g

n

eeds. Total

a

nization, as

e

thods is n

o

n

on-desired

s

s

to be as ac

c

h

ese homeos

t

o

delling is o

f

n

d. We ma

k

i

t is today (th

o be in the f

u

homeostatic

a

ses. For the

a

k

es the organ

i

h

e to-

b

e mode

l

l

e.

i

ng strategic

b

e

ed to pay at

t

a

nd the way i

t

T

he structu

r

n

either e

n

e

at i

t

, depe

n

s

tructure. In

A

m

e of the cul

t

still existed

t

s and peopl

e

hanism) and

p

985. This in

e

Jobs coun

t

ected to fro

m

m

e vision and

t

h some mino

A

pple produc

t

e

of the

b

asi

c

a

cintosh, for

e

w

are and

s

s

ign and pac

k

a

nce, but is d

u

o

n Apple. Pr

i

was produ

c

n

sion cards,

PCs. This st

r

constancy to

o

tatic system’

b

e upheld by

n, each havi

n

g

to Figure

1

h

e entities

w

m

ewhat in

d

a

ble. As hom

e

d

erstanding c

that each e

n

of homeosta

t

r

n, means tha

t

g

ned with t

h

alignmen

t

i

sought by

E

o

t even an

s

ituation. Be

c

c

urate as pos

s

t

atic mechani

s

ften done

w

k

e a mode

l

h

e as-is mode

l

u

ture (the to-

b

mechanisms

a

s-is model t

h

ization or so

m

e

l it would ex

p

b

usiness mo

d

t

ention to the

t

is maintaine

d

u

re, maintai

n

able the e

n

n

ding on wh

A

pple’s case,

t

ure (read str

u

d

. He reinfor

c

e

who did n

o

p

roceeded to

a

itself is a ho

m

t

ered the ch

a

m

1985 to

1

strategy that

w

o

r changes.

R

t

s (e.g. iPho

n

c

characterist

i

example, sea

l

s

oftware, ve

c

kaging. This

u

e to Jobs’s

c

i

or

t

o Jobs’s

c

ing compu

t

which in

c

r

ategy was b

o

k over.

’

s ability to

different

n

g its own

1

, we can

w

ithin the

d

ependent

e

ostasis is

o

ntinuing

n

tity in a

t

ic system

t

some of

h

e overall

i

nside or

E

nterprise

idealized

c

ause we

s

ible, it is

s

ms.

w

ith some

l

of the

l

) and the

e model).

can be

h

is would

m

e part of

p

lain how

d

els for a

structure

d

through

n

ed by

n

visioned

e

ther the

Jobs was

u

cture) of

c

ed it by

o

t fit it (a

a

strategy

m

eostatic

a

nge that

1

997 and

w

as there

R

emember

n

e, iPod,

i

cs of the

l

ed cases,

r

y close

has not

c

onstancy

return to

t

ers that

c

reasingly

r

ought to

maintain

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

20

constancy in the presence of change sometimes has

negative implications (from the point of view of

some observer). Hence, Jobs unwillingness to allow

third party developers to offer applications on the

iPhone in order to maintain its integrity and despite

extensive lobbying from colleagues could have

resulted in serious loss of business opportunities.

Again, Jobs agreed to open the platform only when

he was convinced that he could control the

applications, in itself a research for homeostasis.

We should not forget the polarity principle of

homeostasis where homeostatic mechanisms have

opposing effects. In Apple’s example, Jobs slashed

the majority of Apple’s products and laid off

thousands of people (Isaacson, 2011) in what can be

seen as an attempt to defeat Apple’s homeostatic

system created while he was away.

The perversity principle can explain another

action that saved Apple. Jobs convinced Bill Gates,

Apple’s main competitor, to invest $150M in Apple.

Saving a competitor is a way for the homeostatic

system to not damage itself by being too successful

in moving a state in a given direction. If Microsoft

would have been too successful in driving off

competitors and Apple would have gone bankrupt,

Microsoft would have been more vulnerable to the

anti-trust litigation that was already beginning.

In the case of the Swiss healthcare insurer, the

reversal in strategy can be explained by the

homeostatic system prevailing on the change that is

considered unacceptable. The insurer was

overwhelmed with the new influx of customers from

regions in which it was not traditionally present. It

risked lowering its quality standards. By law, it has

to have a certain reserve of money for each person

insured and it was difficult to have this reserve with

a massive influx of customers. All in all, the insurer

preferred to get rid of many customers in order to

maintain its quality standards and its compliance.

This is a typical homeostatic reaction. Thus, the

organization separates between customers that it

wants to keep and those that it does not, thereby

maintaining the states that it deems important (level

of quality, reserves) unchanged. The value to these

customers may be described as negative. We see that

the homeostatic system does not necessarily

maximize value for a given customer.

Likewise, insuring a revenue stream drives

companies such as banks and mobile phone

operators, to provide better service to customers who

bring large revenues (premium customers). Just

providing value to customers is not the main point. It

is rather insuring a steady or steadily increasing

revenue stream. Maintaining a steady revenue

stream also explains why it is the supplier that

usually fixes the price of a good or service. It is

rarely the customer who fixes the price. If

companies were truly interested in providing value

to customers, they would give their products or

goods for free or would allow customers to negotiate

the price. Similarly, employees do not fix their own

salaries so as to maintain the profit of the company.

When the revenue or profit do decline below

expectations (below what the homeostatic system

defines as acceptable) many actions will be taken at

the same time or successively, as described by the

plait principle, in order to reduce cost, increase sales,

increase research and development, warn

shareholders to lower their expectations, freeze

hiring, renegotiate credit, layoffs etc. Some of these

actions may ignite other actions from other

homeostatic systems, such as strikes and

demonstrations by employees, intervention by

political authorities, and the like.

The obliviousness of homeostatic systems for the

goodness or badness of the constancy they maintain

often results in frustration by change agents. For a

homeostatic system, every change is a threat, not an

opportunity. An opportunity is necessarily a change

to a state kept constant by the homeostatic system

and is therefore an unwelcome occurrence.

Finally, taking homeostasis seriously is to accept

inconsistencies rather than seeking alignment. From

a homeostasis perspective inconsistency can be seen

from the polarity and perversity principle

perspective as a necessary mechanism to insure

survival.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Business modelling methods take the underlying

organization that is supposed to carry out the

strategy defined in the business model for granted.

They assume that the organization will either follow

the defined strategy or that it can be engineered to fit

the strategy. In essence they consider that the

organization has an infinite capacity to change. This

is overlooking the everyday observation that any

organization that has been in existence for even a

few years has built some very strong mechanisms

that resist change.

Any surviving organization has adapted to a

specific environment. It has built a fit (or

congruence) between its environment (customers,

regulators, investors, competitors) and its internal

structure. Changing this internal structure to fit a

different environment is quite difficult. Without

Homeostasis - The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models

21

taking this aspect into consideration, the probability

of successfully implementing a new business model

is very low. Business modelling must take this into

account. Homeostasis is a heuristic device that

provides a plausible explanation to the way

organizations resist change in order to maintain their

identity and therefore survive in a changing

environment. We have shown that homeostasis can

explain both formulation of Business Models (how

to deliver and capture value) and the operational part

(how the strategy is carried out).

Modelling homeostasis does not mean that we

consider that change is impossible, only that change

is very hard to create and maintain. To institute

change, the homeostatic system first must be

neutralized. This is very hard to do because of

Cannon’s four propositions. However hard it is,

resistance to change can have very good reasons that

need to be investigated.

Weinberg and Weinberg (1988) point out that

Cannon doesn’t speak of goals and targets but rather

about constancy. A homeostatic system, therefore,

has no specific goal or target. It simply maintains

some constancy with whatever number of

mechanisms it can bring to bear. If we want to take

homeostasis seriously, being that it provides such a

good explanation of organizational life (and even

life in general), we need to overcome our own

homeostatic system and remove the terms goals,

targets, purpose, ends etc. Rather we need to search

for constancy and how it is maintained. This can be

a radical change in business modelling, a change that

its own homeostasis may be unwilling to allow.

This work should be followed by a more

humanistic view in business modelling, modelling

people and their attitude toward change rather than

the traditional role, business rule, business process

paradigm.

REFERENCES

Chozick, A., 2012. As Young Lose Interest in Cars, G.M.

Turns to MTV for Help. New York Times, March 22,

2012.

Dietz, J.L.G., 2006. The Deep Structure of Business Proc-

esses. Communications of the ACM Vol. 49, No. 5.

Fritscher, B., Pigneur, Y., 2011. Business IT Alignment

from Business Model to Enterprise Architecture, In

Busital 2011, 6th International Workshop on

BUSinness/IT ALignment and Interoperability, LNBIP

83. Springer.

Gordijn, J., Akkermans, J.M., 2003. Value-based

requirements engineering: exploring innovative e-

commerce ideas. In Requirement Engineering. Vol. 8,

No. 2, 114–134, Springer.

Gordijn, J., Yu, E., van der Raadt, B., 2006. e-Service

Design Using i* and e3value Modeling, IEEE

Software. Vol. 23, No. 3.

Hammer, M., 1996. Beyond Reengineering,

HarperCollins. New York.

Hopwood, B., 2002. Whatever Happened to the British

Motorcycle Industry? The classic inside story of its

rise and fall. Haynes.

Isaacson, W., 2011. Steve Jobs. Simon&Schuster.

ISO/IEC 10746-1, 2, 3, 4 | 1995-98. ITU-T

Recommendation X.901, X.902, X.903, X.904. “Open

Distributed Processing - Reference Model”.

Katzenbach, J., 2012. The Steve Jobs Way, strat

egy+business, http://www.strategy-business.com/

article/00109?gko=d331b&cid=20120424enews, ac-

cessed April 2012.

Kilov, H., 1999. Business Specifications: The Key to

Successful Software Engineering, Prentice Hall PTR.

Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., Lampel J., 1998. Strategy

Safary – The complete guide through the wilds of

strategic management. Prentice Hall.

Lankhorst, M.M., Proper, H.A., Jonkers, H., 2009. The

Architecture of the ArchiMate Language.In BPMDS

2009 and EMMSAD 2009, LNBIP 29. Springer.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., 2010. Business Model

Generation.

Regev, G., Wegmann, A., 2004. Defining Early IT System

Requirements with Regulation Principles: the

Lightswitch Approach. In RE’04, 12th IEEE

International Requirements Engineering Conference,

IEEE.

Regev, G., Wegmann, A., 2005. Where do Goals Come

From: the Underlying Principles of Goal-Oriented

Requirements Engineering. In RE’05 13th IEEE

International Requirements Engineering Conference,

IEEE.

Regev, G., Alexander, I. F., Wegmann, A., 2005.

Modelling the regulative role of business processes

with use and misuse cases, Business Process

Management, Vol. 11 No. 6.

Regev, G., Hayard, O., Gause, D.C., Wegmann, A., 2009.

Toward a Service Management Quality Model. In

REFSQ'09, 15th International Working Conference on

Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software

Quality Springer.

Regev, G., Hayard, O., Wegmann, A., 2011. Service

Systems and Value Modeling from an Appreciative

System Perspective. In IESS1.1, Second International

Conference on Exploring Services Sciences. Springer.

Regev, G., Wegmann, A., 2011. The Invisible Part of the

Goal Oriented Requirements Engineering Iceberg, In

BMSD 2011, 1st International Symposium on Business

Modeling and Software Design. SciTePress.

Shishkov, B., Foreword, 2011. , In BMSD 2011, 1st

International Symposium on Business Modeling and

Software Design. SciTePress.

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

22

Sowa, J. F., Zachman, J. A., 1992. Extending and

formalizing the framework for information systems

architecture. IBM Systems Journal Vol. 31. No. 3.

Spohrer, J, Riecken, D., 2006. Special issue: services

science. Communications of the ACM Vol. 49 No. 7.

Vickers, Sir G., 1987. Policymaking, Communication, and

Social Learning, eds, Adams, G.B., Forester, J.,

Catron, B.L.,Transaction Books. New Brunswick NJ.

Weinberg, G. M., Weinberg, D., 1988. General Principles

of Systems Design, Dorset House.

Winograd, T., Flores, F., 1986. Understanding Computers

and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design, Ablex.

Norwood, NJ.

Zachman, J. A., 1987. A framework for information

systems architecture. IBM Systems Journal Vol. 26.

No. 3.

Homeostasis - The Forgotten Enabler of Business Models

23