Can Fuzzy Decision Support Link Serial Serious Crime?

Don Casey and Phillip Burrell

London South Bank University, Borough Rd, London, SE1 0AA, U.K.

Keywords: Crime Linkage, Decision Support, Fuzzy Clustering.

Abstract: The problem addressed is one of great practical significance in the investigation of stranger rape. The

linkage of these crimes at an early stage is of the greatest importance in a successful prosecution and also in

the prevention of further crimes that may be even more serious. One of the most important considerations

when investigating a serious sexual offence is to find if it can be linked to other offences; if this can be done

then there is a considerable dividend in terms additional evidence and new lines of enquiry. In spite of a

great deal of research into this area and the expenditure of considerable resources by law enforcement

agencies across the world there is no computer-based decision support system that assist crime analysts in

this important task. A number of different crime typologies have been presented but their utility in decision

support is unproven. It is the authors’ contention that difficulties arise from the inadequacy of the adoption

of the classical or ‘crisp set’ paradigm. Complex events like crimes cannot be described satisfactorily in this

way and it proposed that fuzzy set theory offers a powerful framework within which crime can be portrayed

in a sensitive manner and that this can integrate psychological knowledge in order to enhance crime linkage.

1 INTRODUCTION

The need for computerised systems to support the

work of crime analysts and investigators has been

recognised for some time. The authors of an

influential study into linking serious sexual assaults

remarked that:

The ultimate goal is to create a computer-based

screening system that will allow routine and

systematic comparison of serious offences on a

national basis , selecting cases on the basis of

their behavioural similarity that are appropriate

for more detailed attention by detectives or crime

analysts (Grubin et al., 2000)

And this view has been reinforced by an eminent

criminal psychologist:

The development and test of theories and

implementation of findings into computer-based,

decision-support systems … has to be the proper

basis for any professional derivation of

inferences about offenders. (Canter, 2000)

The problem at the heart of crime linkage resides in

the need for an adequate typology of offences but

the search for an effective system has proved

elusive.

The most influential crime classification system

has been that proposed in the Crime Classification

Manual (Douglas et al., 1992) which is the work of

senior Federal Bureau of Investigation agents. It

advances the notion of an organised-disorganised

dichotomy and was developed from interviews with

offenders (Ressler and Douglas, 1985). The basis of

this approach is that crimes can be differentiated by

the level of planning and organization associated

with them and the authors extend this to assert that

the dichotomy can be applied to the offender so that

organised and disorganised crimes are committed by

individuals who can be differentiated in discrete

groups with distinct characteristics. Very serious

objections have been made to the methodology

employed by the FBI. Only 36 offenders were

interviewed, no attempt was made to ensure this

group was representative and the interviews

conducted were not structured or consistent. An

evaluation of this typology (Canter et al., 2004)

applied to 100 serial murderers provided no support

for it.

In the most comprehensive research programme

into the linkage of serious sexual offences (Grubin et

al., 2000) the authors propose

Our starting premise is that rape attacks can be

organized into distinct types

383

Casey D. and Burrell P..

Can Fuzzy Decision Support Link Serial Serious Crime?.

DOI: 10.5220/0004332403830388

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2013), pages 383-388

ISBN: 978-989-8565-39-6

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

It is certainly the aim of investigation of any

field to initially classify the objects contained within

it but it is the hypothesis of this paper that although

rapes can be organized into types that these will be

far from ‘distinct’. And that the attempt to

discriminate between crimes in this way is likely not

only to be barren but actively misleading in that they

will be forced into mutually exclusive types that will

misrepresent their complexity; a perspective arrived

at after many years of research by one of the area’s

foremost investigators

… assigning criminals or crimes to one of a

limited number of ‘types’ will always be a gross

oversimplification. (Canter, 2000)

Canter and his associates who are identified with

Investigative Psychology have published numerous

studies (Hakkanen et al., 2004); (Santilla et al., 2003)

on sexual assault, homicide and other serious crimes

but have been unable in any of them to construct a

satisfactory typology with even the most relaxed

rules of assignment (Salfati and Canter, 1999).

Grubin is obliged to propose a 256 element

taxonomy in which many of the elements are

redundant, a classification system in which many if

not most of the elements will never occur cannot be

satisfactory. The assumption of the crisp set

paradigm in this research appears to be the cause of

the problems relating to these difficulties. This can

be illustrated by a simple description of a crime such

as ‘a very violent assault on a middle-aged woman

by a young man’ which cannot be properly expressed

in terms of crisp sets. It can lead to either the

misallocation of fundamentally different offences to

the same place or to crimes that bear strong

resemblances to each other being regarded as entirely

unconnected, a phenomenon referred to as linkage

blindness (Egger, 1990) of which researchers are

fully aware but have been unable to address.

In the analysis of serious crime, particularly

sexual offences, there are two computer databases

that dominate: the Violent Criminal Apprehension

Program (ViCAP) introduced by the F.B.I and the

Violent Crime Linkage System (ViCLAS) first

developed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

(RCMP). ViCAP is used predominantly in the USA

while ViCLAS is employed throughout most of

Europe .Both systems are essentially repositories of

criminal records that analysts search using their

training and expertise in order to link offences. This

is achieved employing straightforward Boolean

searches on groups of variables deemed to be

significant. There has been no decision support

system devised to assist in this task and no attempt

has been made to incorporate the results from

psychological research into crime linkage.

2 DATA

We have been fortunate in being successful in

obtaining data on 574 serious sexual offences from

the Serious Crimes Analysis Section of the U.K

National Policing Improvement Agency. We have

excluded those offences that do not relate to serial

stranger rapes, by which we mean a set of rapes

committed by a single individual unknown to the

victim. This results in a much narrower dataset (n =

112), development set n = 83, test = 29). The

development set consisted of 28 series, mean length

2.96, while the test set comprised 11 series with a

mean length of 2.64.

The dataset made available contained 22 single

or ‘one off’ stranger rapes which allowed variants on

the set to be constructed that could be regarded as

more realistic in that they contained a mixture of

both serial and individual offences. In the first

instance these were added to the 29 offences in Test

Set 1 to produce Test Set 2 (n = 51). By using this

set of crimes the effect of a substantial group (>

40%) of unlinked offences in tests could be

observed. Both Test Set 1 and 2 used the value of

variables derived from Development Set 1. In order

to replicate the development of a crime database

over time the entire set of 112 linked crimes was

used as Development Set 2. As with the other

development set this pool of offences generated its

own value for variables; they were found to be

somewhat different but in line with the first set.

Finally as before and for the same reasons this set

was combined with the 22 single offences to

produce a composite set of 134 linked and unlinked

offences.

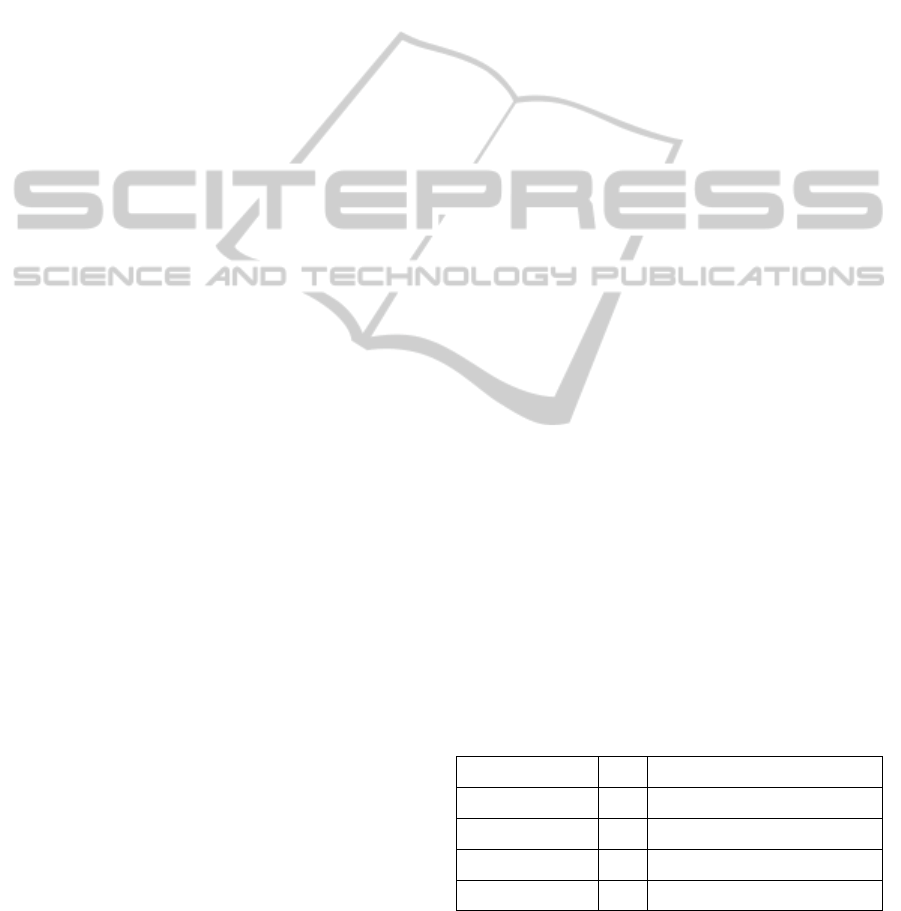

Table 1:Development and test datasets.

n=

Development 1 83 83 linked crimes

Test 1 29 29 linked crimes

Test 2 51 29 linked, 22 unlinked

Development 2 112 112 linked crimes

Test 3 134 112 linked crimes, 22 unlinked

ICAART2013-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

384

3 CRIME AND FUZZY SETS

Fuzzy set theory (Zadeh, 1965) allows us to

represent crimes and criminals as highly descriptive

objects in the concept space and to undertake

experimental procedures to discover what are the

most significant differentiating features using

mathematically and logically sound methods

The Grubin study was taken as a starting point

for modelling stranger rape linkage because it was

focussed on this crime, had used the most similar

data and was the most lucidly expounded. The basis

of this approach was to identify four ‘dimensions’ of

criminal behaviour: Control, Sex, Escape and Style.

The last of these was a late addition by the authors

and was found to be of very limited use. It was

therefore discarded and the first three employed. A

total 44 variables were found to directly or indirectly

correspond to those employed in the earlier research.

On inspection the Control and Sex dimensions both

appeared to have a natural division in their variables

in that Control consisted of overtly violent actions

such as assault and use of weapons and other more

enabling actions such as engaging the victim in

conversation. The Sex dimension similarly divided

into those actions that constituted rape and others

such as kissing. Consequently, in testing, offences

were characterised by the original dimensions (3D);

Control, Sex1, Sex2, Escape (4D2S); Control1,

Control2, Sex, Escape (4D2C); and all five

dimensions (5D). By extending the number of

dimensions it was hoped that an optimum

configuration would emerge

The number of variables in each dimension was

distributed as: Control (19), Sex (14), Escape (11),

Control1 (12), Control2 (7), Sex1 (6) and Sex2 (8).

3.1 Membership Functions

We can define the universe of crimes as a data set

(X) of n elements

,

,

,….

(1)

Where each crime (

) is defined by j features or

variables

,

,

,….

(2)

The variables constitute behavioural dimensions as

above. A problem arises with these dimensional

concepts because they cannot be incrementally or

hierarchically scaled. This makes the use of a

conventional membership function difficult. In order

to overcome this we have proposed that the amount

of these activities can be measured, i.e. the number

of separate sexual, controlling or escape-centred

actions within each crime,

.These variables have

dichotomous values that do not reflect their value in

contributing to the distinctiveness of the crime in

which they occur. However it can be posited that

each variable,

be associated with a value

that

represents a weighting based upon its prevalence in

the dataset of n crimes. In order to assign a value to

each variable that reflects this frequency the

reciprocal of the sum of its occurrences is taken. As

a result if the variable were to occur in every crime it

would have a value of 1/n while if it were to occur

only once its value would be equal to 1 with all

intermediate frequencies being assigned

corresponding values. This simple calculation

assigns an appropriate value to each variable; thus

the variable

is assigned a value or weight

by

w

1

∑

x

(3)

Once each variable has a value it is a simple matter

to sum the values of all the variables found in each

crime to give it a score,S

, n that dimension

.

(4)

The degree of membership can then be calculated by

normalising this score by dividing it by the highest

score encountered in the dimension

max

:1,….

(5)

The result is intuitively satisfying in that the score

attained is related directly to the most controlling or

sexually demeaning, etc., crime encountered up to

that point. It also means that a rudimentary form of

learning can take place in that as more crimes are

added the scores across dimensions for each crime

will be liable to change and its position in the sample

space will move. This could be taken to replicate the

manner in which experience affects the performance

of skilled users.

The membership function also derives closely

from the techniques used in Investigative Psychology

(Canter et al., 2003) which emphasizes the frequency

of variables and their co-occurrence within crimes.

An example of degrees of membership for two series

in three dimensions is given at table 2.

3.2 Fuzzy C-means Clustering

Having established the degrees of membership from

the development dataset for each crime in all four of

CanFuzzyDecisionSupportLinkSerialSeriousCrime?

385

the dimensional structures it was possible to

investigate the relationship between them and how

they were distributed in the concept space through

clustering.

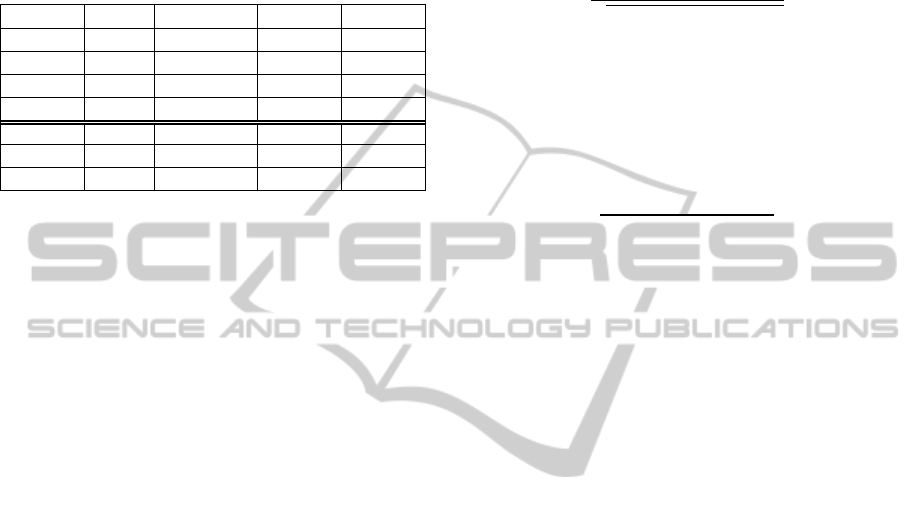

Table 2: Three Dimensional (3D) memberships.

Crime series Control Sex Escape

1 1 0,38 0,17 0,15

2 1 0,38 0,22 0,08

3 1 0,32 0,24 0,07

4 1 0,34 0,34 0,37

5 1 0,34 0,10 0,14

6 2 0

,

32 0

,

06 0

,

00

7 2 0,27 0,14 0,16

8 2 0,38 0,03 0,09

Fuzzy c-means clustering (Bezdek, 1981) is the

most widely used fuzzy clustering strategy and

effectively addresses the difficulties raised by Canter

of exclusive types of crime. It does this by defining a

set of fuzzy sets on the universe X so that the sum of

degrees of membership of all the classes of any

datapoint is unity, there will be no empty classes and

no class that contains all the datapoints. This is an

iterative optimisation technique of the objective

function below where a degree of fuzziness 1 ≤ m <

∞ is specified and elements are assigned degrees of

membership of the clusters until some termination

criterion has been reached.

(6)

is the degree of membership of

in cluster j and

is the cluster centre

Cluster centres are initially distributed randomly

and are guaranteed to converge however there is no

technique to determine the optimum number for any

application. Therefore the number of clusters (j) was

specified from 2 to 5, 6 clusters produced

inconsistent results. It was also possible to vary the

degree of fuzziness (m) from 1.25 to 3 in increments

of 0.25. A value of m = 1 equates to a crisp partition

of the data which becomes correspondingly fuzzier

as it increases. There is no agreed best value for m

although around 2 is often cited (Ross, 2004).

3.3 Fuzzy Similarity

Clustering returned the membership of j fuzzy

clusters for each offence. Two similarity methods

were used to evaluate the strength of the

relationship,

, between the objects

and

.

Cosine amplitude reflects the size of the angle

between them; where they are colinear the value is

unity and when they are most dissimilar, i.e., at right

angles the relationship has a value of 0.

Here there are n objects (crimes) represented in

m-dimensional space

∑

∑

∑

(7)

where i, j = 1, 2 … n

The max-min method is simpler than cosine

amplitude and uses max, min operations on pairs of

datapoints to establish similarity in a straightforward

manner.

∑

,

∑

,

(8)

where i, j = 1, 2 … n

As a result an n x n similarity matrix was

generated for all values of fuzziness (m) and number

of clusters (j) for both methods. The values in each

row (n) were then rank-ordered to show the relative

closeness of all the other crimes to the

offence.

For the development set of 83 crimes these values

range from 1 (closest) or most similar to 82 for the

most dissimilar.

4 RESULTS

The rank-ordered similarity distance for each dataset

was computed to produce an n x n matrix and the

mean and median for the total of those comparisons

between serial offences recorded. It should be noted

that these distances were not symmetrical: if

and

have a similarity of 0.8 it does not follow that

they are equally distant from each other.

These results should show distances of ≈ n/2

between linked crimes if they are randomly

distributed. However it was found that for virtually

all combinations of dimensions, clusters and

fuzziness values that distances were consistently

below this level and often considerably so. Table 3

shows the best results for each set; medians are

shown as they would best represent the search

strategy of analysts in searching for matches. In

addition in nearly all results and particularly the

more successful ones there was an evident positive

skew indicating that successful matching was

concentrated towards the low distance.

The exceptional performance obtained with Test

ICAART2013-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

386

Set 2 suggests that the environment of this dataset in

which serial offences are a bare majority may

substantially enhance the outcome. This is an

interesting result in that although there are no

figures to indicate the ‘mix’ between serial and

individual offences because of partial detection

rates; it is likely to replicate ‘real life’ in which a set

of stranger rapes is composed of both serial and

single offences.

Results show that although there is a marked

advantage in using the methodology and techniques

outlined here there is no convincing combination of

number of clusters or levels of fuzziness that

consistently returns optimum distances.

Table 3: Median distances between linked crimes.

n=

lowest

median %

n/2

dimensions clusters m =

Dev Set 1 83 < 50% 3D 2

low to

medium

Test Set 1 29 <35% 3D 3 all vals

4D2C 4,5

low to

medium

4D2S 4 all vals

Test Set 2 51 <25% 3D 4,5

low to

medium

4D2S 4,5 all vals

Dev Set 2 112 <55 % 3D 2 all vals

5

med to

high

Test Set 3 134 ≈ 50% 4D2C 4

low to

medium

5 low

4D2S 5 medium

5 CONCLUSIONS

A recent report into rape investigation in the U.K.

(HMIC/HMCPSI, 2012) detailed the problems of

productivity in terms of analysis in that only around

25% of suitable crimes submitted were analysed and

that a backlog was building up that might never be

cleared. These are some of the most serious crimes

that occur in society and the need for more advanced

techniques to assist investigators is clear.

This research has demonstrated that fuzzy

methodology can be used successfully in

representing serious crimes in a sensitive manner

that reflects their complexity and builds on insights

from criminal psychology.

Although attempts have been made to associate

stranger rapes in order to enable linkage there has

been no input from Artificial Intelligence or

Decision Support and they have been purely

psychology-based. This is surprising in view of the

clearly stated views of leading researchers. The

research presented here has for the first time

endeavoured to find the strength of similarity

between offences in the way that crime analysis

requires.

The problem of rigid typology that has hampered

this area of research is precisely the one that fuzzy

sets avoid. Because of the nature of the area under

investigation any crisp classification method is

bound to fail. Either a large number of crimes elude

classification as in Investigative Psychology or a

highly redundant typology of stranger rape, which is

itself a small subset of rape has to be proposed.

Reference has been made to the possibility of

increasing the productivity of analysts but it is also

possible and perhaps probable that given assistive

technology that the quality of analysis would

improve. Given new, and better, ways of achieving

their goals expert users are highly likely to adapt and

improve their expertise.

The results obtained here strongly suggest that

the methods used can be of considerable value in

crime linkage and that further research may well

refine dimensionality and clustering to produce even

more useful inferences.

If this can be done then the consequences may

feed back into criminal psychology in that cluster

centres can be regarded as prototypes of criminal

action and be interpreted as a usable typology. And a

circle of effective advance and cross-fertilisation

result.

It may be this approach can yield the

psychologically valid and meaningful set of numbers

(Canter, 1985)

called for in the earliest days of

research into this area .

REFERENCES

Bezdek, J., (1981). Pattern Recognition with Fuzzy

Objective Function Algorithms. New York: Plenum.

Canter, D., (1985). Facet theory: approaches to social

research. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Canter, D., (2000). Offender profiling and criminal

differentiation. Legal and Criminological Psychology,

5, 23-46.

Canter, D., Alison, L., Alison, E., & Wentink, N., (2004).

The Organized/Disorganized Typology of Serial

CanFuzzyDecisionSupportLinkSerialSeriousCrime?

387

Murder. Myth or Model ? Psychology, Public Policy

and Law, 10(3), 293-320.

Canter, D., Bennell , C., Alison, L., & Reddy, S., (2003).

Differentiating Sex Offences. Behavioural Sciences

and Law 21.

Douglas , J. E., Burgess , A. W., Burgess, A. G., &

Ressler, R. K., (1992). Crime classification manual: A

standard system for investigating and classifying

violent crime. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Egger, S. A., (1990). Serial murder: an elusive

phenomenon. New York: Praeger.

Grubin, D., Kelly, P., & Brunsdon, C., (2000). Linking

Serious Sexual Assault through Behaviour Home

Office Research Study 215. London.

Hakkanen, H., Lindof, P., & Santtilla, P., (2004). Crime

Scene Actions and offender characteristics in a sample

of Finnish stranger rapes. Journal of Investigative

Psychology and Offender Profiling, 1(2), 153-167.

HMIC/HMCPSI, (2012). Forging the links: Rape

investigation and prosecution. A joint Review by

HMIC and HMCPSI: H.M. Inspectorate of

Constabularies / H.M. Crown Prosecution Service

Inspectorate.

Ressler R. K, & Douglas, J. E., (1985). Crime Scene and

Profile characteristics of organized and disorganized

murderers FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, 54(8), 18-

25.

Ross, T., (2004). Fuzzy logic with engineering

applications. Chichester: Wiley.

Salfati, C., & Canter, D., (1999). Differentiating Stranger

Murders: profiliing offender characteristics.

Behavioural Sciences and Law, 17(3).

Santilla, A., Hakkanen, H., & Fritzon, K., (2003).

Inferring the Crime Scene Characterstics of an

Arsonist. Interrnational Journal of Police Science and

Management, 5(1).

Zadeh, L., (1965). Fuzzy Sets. Information and

Control(8), 228-353.

ICAART2013-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

388