Intercultural-role Plays for e-Learning using Emotive Agents

Cat Kutay

1

, Samuel Mascarenhas

2

, Ana Paiva

2

and Rui Prada

2

1

Computer Science and Engineering, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

2

Instituto Superior Técnico-UTL, INESC-ID, TagusPark, Porto Salvo, Portugal

Keywords: eLearning Culture, Emotive Agents.

Abstract: This paper presents joint work between an Australian team developing role-based games for experiential

learning of Aboriginal culture, and a Portuguese research department developing interactive modules to

create believable agent reactions in virtual environments. The game incorporates recorded stories in an

online system to teach culture. Teaching scenarios group the narratives along a learning path, but their

presentation in the game requires an emergent narrative to provide the flow through agents that reacts to the

players’ actions and enacts significant aspect of the culture. We present here the existing agent modules and

how they will be used in this project and the challenges in extending the work to this new domain.

1 INTRODUCTION

When confronted with cultures with widely different

priorities and forms, we are often quite unaware of

the effect these rules can have on relations between

individuals and groups. In this project we are aiming

to teach a historical perspective of the Aboriginal

culture of Australia that has been largely subsumed

and denied within the mainstream culture. However

the culture continues to exist and individuals

continue to practise the rituals, adhere to the values

or norms and learn from childhood how to read the

symbols of the culture (Hofsted, 1991).

The teaching process to be used is highly

experiential and will incorporate role-playing within

a game that will be built from stories provided by

Aboriginal people. The focus of the teaching is an

example amalgamated from the Aboriginal kinship

systems of Australia.

The kinship system provides a series of rules that

are important within the highly mobile cultures for

maintaining genetic health and communal

responsibilities, but also forms the basis of a highly

complex process of knowledge sharing and learning.

This lends itself to the process of developing an

emergent, self-generated narrative from community

stories (Spaniol et al., 2008) by using an agent-

modelling system to provide realistic agents within a

culture that is different to that of the player (Nazir et

al, 2008); (Endrass et al., 2011) and to support

learner modelling (Aylett et al, 2005).

Simple scenarios are created for the teaching

framework, and then presented in a game format that

varies with the player’s interactions and the

interaction of the agents on the screen through the

agent modelling.

2 LEARNING SYSTEM

The learning system is a Unity game with animated

characters presenting video narratives from

Aboriginal people. The system is to be used at

University as part of the assessable coursework, to

enable students and staff to engage with the culture

and be immersed in the relations between agents.

First the Aboriginal contributors are shown the

video information on the kinship that will also be

shown to the game players. This introduction

material explains the kinship system, using a simple

group format based on sixteen types of group

members, derived from eight generational divisions

and two marriageable divisions. Each of the sixteen

members of the group has specific relation and level

of responsibility to each other member.

Then the authors are asked to contribute stories

of their experience of the various aspects of kinship.

These stories are recorded and presented in the game

as audio, or usually video, recordings.

The authors are then asked to tag their stories.

These include the subject theme of the story (eg

Education, Law, Social Work), the relevant theme

Kutay C., Mascarenhas S., Paiva A. and Prada R..

Intercultural-role Plays for e-Learning using Emotive Agents.

DOI: 10.5220/0004335603950400

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2013), pages 395-400

ISBN: 978-989-8565-39-6

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

from the introductory material, the kinship role to be

given to their character, and the type of content

(whether it be about living in Aboriginal culture,

living between cultures or the effect of denial of

culture) plus any suggested questions to raise after

the story is viewed. At present we allocate them an s

simple agent that presents their story in the game.

We have developed prototype games that provide

a simple environment for users to navigate a

collection of narratives by Aboriginal people

discussing issues relating to the introductory

material. The aim of this extension work is to

provide parameters that the authors can select for

their character that will guide agent interaction in the

system and provide a representation of cultural

relations to the user. Hence we will add an interface

to select some of the agent modelling parameters

discussed below.

To develop this into a learning system we are

using scenarios that are based on future experiences

our graduates may have with Aboriginal clients and

employers, as when running a health service or

conducting land claims. The scenarios are simple

learning paths that provide an introduction to set the

scene, a goal for the student to complete and then

certain challenges along the way. The example used

in this paper is:

The student is going to work as a teacher at a

school in western Sydney with a high aboriginal

population. They are assigned a kinship role within

the local community. They will be then shown the

kinship role of each agent as they move through the

game. They can work out their relation to that

person and act accordingly or ignore these rules.

The stories that will be available to hear will

therefore be selected on the basis of the main theme

being Education, and a selection of different kinship

relations to the user.

Some of the challenges are presented here under

the kinship theme they relate to:

Totem: The player will be invited on a hunting

trip to collect/catch their own totem. Another elder

person of the same totem will be nearby whom they

should ask for permission to hunt.

Skin Name: The player should speak to people

of the appropriate skin or the stories that are offered

will become more discouraging and illustrate

Aboriginal distrust of the education system.

Communication: A non-Aboriginal character

will prevent the player from teaching the material

they wish to teach. They should call a community

meeting to discuss this or they can confront the other

character alone.

Language: The school library will contain only

simple books even though it caters to high school

students. The player may not notice this or ask the

community why this is. They can then be told stories

on the user of pidgin in teaching Aboriginal people,

government control of education, and so on.

The scenario forms a series of thematic spaces or

rooms the player will go through. At the end of each

room they can be asked questions, or any narrative

can conclude with questions. The aim of using the

agent modelling is to reduce scripting of the

scenarios and increase the automated interaction

between player and agents, as well as between

agents in the game. This will also enable a player to

play the game twice and have a different experience,

or be able to talk with their peers and retell different

stories.

3 AGENT MODELS

The initial agent models used are generic characters

available in Unity, but these will be adapted to the

culture of the contributors by using some

characteristic mannerisms and patterns of behaviour,

including:

Frequent hand signalling related to sign language

Avoidance of direct eye contact

Subtle rather than overt use of emotions

The level to which these aspects will be

portrayed will be selected by the author so as to

reflect the nature of their story. For instance authors

may wish to present a cultural denial story with a

more direct facial approach as this represents honest

of the story in the mainstream culture. By adopting

behavioural aspects to the culture of the player we

can change the users perception to match the

learning needs of that story (Endrass et al., 2011).

However as mentioned above, the actual conveying

of story is usually done by video so the stance and

tone during the story is set directly by the author.

The agent modelling will manage the pre-

narrative and post-narrative actions of the in-game

agents, such as selecting who approaches the player,

who avoids them and what feedback is selected

when the player has finished listening to a story or

exits a theme in the scenario. It will also manage the

score of the player and the reaction of the agents to

this score, which will be effectively a measure of the

community trust. This idea is expanded further in the

next section. Here we look at how the different

cultural aspects will be handled by different parts of

the system.

3.1 Agent Appraisal Modelling

The timing and level of the reaction of the agents to

the player, and interactions in the game between

agents will need to be developed using agent

modelling to create a flow to the scene. For instance

if the player is losing many points, the authors with

cultural denial stories will be selected for the scene.

The software component that drives character

behaviour will be based on FAtiMA (Dias et al,

2011) an agent architecture that uses the OCC

appraisal theory (Ortony et al, 1988) which defines

the concept of emotion as bipolar or valenced

reactions to an event. The emotion is generated from

a subjective evaluation according to the agents’

goals, standards and beliefs.

The advantage of using the OCC-model for

modelling emotions is that it provides a formal

description of many independent affective outcomes

The OCC model is used to provide a relative

emotional state based on individual events, actions,

and symbols:

Rituals: Aboriginal society is rich in rituals that

provide guidance for evaluating the consequences of

an event.

Values: Aboriginal knowledge system provides

clear values about environmental care and respect

for others, which guide the evaluation of the actions

of others.

Symbols: Aboriginal symbolism will be used only

in the use of sign language and modelling mentioned

above which define what is appealing or not.

3.2 Agent Deliberative Modelling

The deliberative layer of FAtiMA uses the perceived

event to activate predefined goals, and the agent will

then select between competing alternative goals.

Here the cultural goal selection process calculates

the cultural utility for active goals.

We use rituals as corresponding to a predefined

sequence of actions that should be performed once

the context of the ritual is reached. This is

implemented in the architecture by creating a special

type of goal that includes a predefined plan, and

with the parameters that compose a ritual.

When a ritual is initialised, the planner creates an

initial plan with the steps required and can alter the

plan to achieve the goal of the ritual.

3.3 Agent Reactive Modelling

The following dimensions of cultural difference

between the agents and the player, and between

agents are used to represent different cultural

approaches. A survey reported in Reece et al (2010)

provided the initial modelling, however this study

was for a specific culture of Northern Queensland.

Power Distance Index PDI: In Aboriginal cultures

people tend to regard others as equals while

retaining some formal status. In mainstream

Australian society respect for more experienced

members of society has been lost.

Individualism IDV: Aboriginal cultures are high in

collectivism, with individuals integrated into groups

with reciprocal responsibilities. In mainstream

Australia, people stress the importance of personal

achievements and individual rights.

Masculinity MAS: Aboriginal cultures can be

matrilineal or patrilineal, while the patrilineal

cultures have respect for the co-existing women’s

society within their own culture. Therefore

relationships and quality of life are more important

within the cultures. Mainstream Australia is a very

masculine culture so favours assertiveness, ambition,

efficiency, competition, and materialism.

Uncertainty Avoidance Index UAI: This

dimension indicates to what extent people prefer

structured over unstructured situations. In

mainstream Australia, people have as few rules as

possible, and unfamiliar risks and ambiguous

situations cause less discomfort. In Aboriginal

cultures, people tend to have strict laws and rules

and also various safety measures to avoid the novel.

Long-Term Orientation LTO: Indicates to what

extent the future has more importance than the past

or present. Australian Aboriginal culture are viewed

as oriented towards present benefits, but their

traditions are highly adaptable to the changing

climate and conditions, while still fulfilling

reciprocal social obligations. The mainstream

culture focus on progress and change but have a

short term orientation.

3.4 Combining the Modelling

A similar application developed to enable history

students to learn from a past culture (Bogdanovych

et al., 2009) uses cultural norms of behaviour

characterised through the notion of cultural

institutions, as the carriers or knowledge. In this

previous example the culture was based around the

technology and environment of the society, and the

cultural institutions consisted of (amongst other

aspects) roles, relationships between roles, flow

between roles and norms of behaviour for roles.

However this project modelled explicit cultural

aspects that have to be individually coded. Work

with agent models such as FAtiMA deal with

implicit cultural aspects that can have an explicit but

subtler reactive effect on character behaviour, and

also handle the interaction between the different

cultural dimensions and social norms.

4 AGENT MODEL DESIGN

For these reason we are investigating the use of

FAtiMA architecture for modelling this culture, and

we will use the following three modules:

Cultural Component: Implements cultural-

dependent behaviour of agents through the use of

rituals, symbols and cultural values, relating to the

above dimensions. This component determines a

Praiseworthiness appraisal variable based on cultural

values and the impact actions have on the

motivational states of the agents. For instance, the

more collectivistic the agent’s culture is, the more

praiseworthy is an action that positively affects the

need of others in the group to the detriment of the

agent’s own needs. This would implement the

Aboriginal system of knowledge sharing that links to

the totem groups and prevents the holder of a totem

from eating their totem while providing knowledge

to others how to hunt the animal.

Social Behaviour: Provides modification of

decision making in implementing cultural rules

depending on the social importance of the agents

and rules of interaction that are denoted by the

kinship relationship.

Theory of Mind Component: This creates a model

of the internal states of other agents. This component

determines the desirability of an event for others by

simulating their own appraisal processes.

Also the Reactive and Deliberative Components are

used by these components.

4.1 Modelling Aboriginal Culture

The features of social relationships that lend

themselves to automated scripting, and hence simply

development of the games, are:

Story selection by tagging:

Kinship relations that dictate the generational

status and rituals of interaction between characters.

This will also help randomise the stories that

agents wish to share with the player. Since the

player’s tag is randomly assigned, and the main

knowledge sharers will be their parents and

grandparents, mostly stories with these tags will be

shared in a session.

Knowledge sharing processes where knowledge is

shared with the learning in increasing order of

complexity, within a theme. Hence an author’s

video may be divided into introduction and fuller

version as well as author being able to tag their

stories as being further examples of another story

in the repository. Also the communication needs

will effect story sharing in that it is important for

those of specific totems to share.

Agents will know which other stories are relevant

to either their story or the player’s tag, so can

advise on who to talk to next through the text

interface

Using stories from different uploads to the

repository so the knowledge is continually

updated, but old stories retain relevance.

Select different narrative styles for each player to

hear to help the learning process for different

learning styles. The narrative style will be tagged

on each narrative.

Movement of Agents in game scene:

Agents will approach the user if they have a story

to share and will move away if they do not wish to

share. This desire be assessed using the above

rules (PDI).

If the player focuses on stories from only a few

people, others will distrust them but will meet

together on screen away from the player,

reinforcing collective knowledge sharing (IDV).

Agents will not always be there to give an

expanded story, the player will be told they have

gone on business. If the player waits for them then

they will get bonus information to help them in the

scenario (LTO).

Agents will tend to move in groups based on their

sex, but each role in a scenario will be taken

alternatively by different sexes (MAS)

Agents will tend to avoid the player at first them

become more used to their presence as they are

seen to learn more stories (UAI).

Generation of Feedback to learner using text:

The initial scenario will be scripted, with

introduction material and pointers along the way to

guide the player

In addition to telling the stories, agents will have

the option to add text based comments or

questions. Authors may add a question to be

displayed at the end of their narrative

The user can select certain actions in the

community, such as group meetings or hunting

trips. The number of agents that respond will

depend in the level of trust they have in the

community.

Community Trust as the assessment parameter:

The level of trust of a player within the community

will be an influential factor in agent interactions

with the player. This will be assessed from the

number of stories heard, who from, and the time

the player has been in the game (hanging around

the community)

Trust will also be evaluated from the player’s

response to certain scenario situations, that is, the

player’s score so far.

When trust is lost within the game, the user will

have options to regain trust through a process

where they are required to hear the stories of how

their actions, and the actions of those before them,

have affected people’s lives.

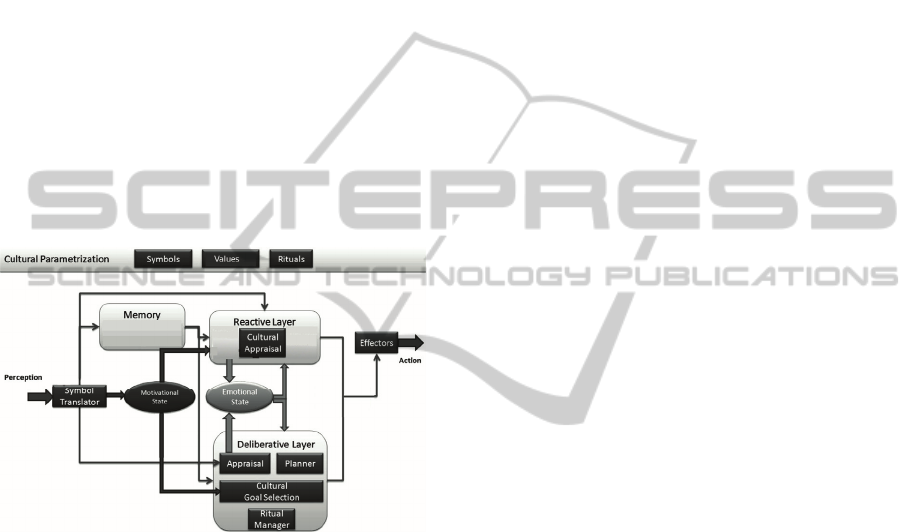

4.2 Modelling Process

The agent modelling is based on the FAtiMA model

(see Figure 1) and relates to the components shown

as follows:

Figure 1: Adapted from the full FAtiMA Architecture

presented in Mascarenhas et al. 2010.

The scenario will set up the overlying rules and

assessment point system, specifying the scene and

what is a good or bad goal in the game.

The rules relating to rituals as goals for the

agents will be updated by the ability to complete a

ritual given the state of the world and the other

agents, and players, responses.

The rules of interaction of characters with each

other will be based on a group of parameters relating

to the above five cultural aspects with strong

preference for the Aboriginal viewpoint.

The agent’s mood is evaluated using the OCC

theory of emotions as a method of appraising events

or situations for aspects such as Desirability and

Praiseworthiness that are handled by the cultural

reactive appraisal layer.

To express the mood evaluated by FAtiMA,

individual animations will be selected for the agent’s

character by the author. This will specify the limits

of the expressiveness of that character, such as how

much the character expresses happiness or sadness.

Indigenous users will evaluate the modelling of their

agent’s parameters.

5 INITIAL SCENARIO

The first scenario being run in FAtiMA describes the

protocol of hunting. In the scenario the user has been

asked by an agent to join a hunting expedition.

They will learn social protocols from the agents

if they follow the correct protocols as given to them.

These relate to four components:

Totem: they may not be involved in a hunt of their

own totem.

Skin name: They should not speak directly to their

grandparent (two skin level up) without introduction.

Communication: They should not confront people

directly for request but first engage in conversation.

Language: They should not assume that agents can

speak or understand English, but include them still

in their communication through other means.

We use a scenario that specifies the agents and

their parameters relating to the four components

above; the cultural rules that the user is to extract

from their experience; the actions agents and the

user can take in the scenario, and the single goal to

join the hunting group. The emotional thresholds are

set once across all agents.

The user can then step through a selection of

options as to how they deal with the problem, and

receive the response that is appropriate to the

cultural rules plus feedback from the mood of the

agents, or they can ask for assistance and watch the

agents step through the same process with the user

as observer.

5.1 Modelling Issues

The existing modelling system calculates the user’s

Social Importance within the culture. This provides

an additive value of the user’s actions within the

culture, and forms a transparent marking scheme.

However issues that arise in the existing system

when modelling such a different culture include:

Cyclical nature of Aboriginal relationships

Lack of good-evil dichotomy to guide heuristic

evaluation of actions

Tracking the complex requirements of obligation

and responsibility.

6 CHALLENGES

The first challenge we face in this work is the

development of a range of cultural ‘stereotypes’ that

are acceptable to the Aboriginal authors using the

system as valid representations of their culture or if

they feel other aspects are more significant.

The next relates to the creation of rules that

reflect the balance between the cultural rituals and

the social values and cultural dimensions that

moderate the application of these rules. While

Aboriginal culture has many rituals, the complexity

and subtlety of these has been developed by one of

the oldest cultures in the world, so it will be hard to

emulate these using computer modelling.

Then we will look at the aspects of culture that

are not represented in the existing agent modelling

system as listed above. These are also significant for

the learner modelling system within the game as the

kinship system also relates to the teaching models

used for knowledge sharing with the community.

For instance the Mood of the agents will reflect their

ability to carry out their social obligations, which

will depend on the hindrance or compliance by the

user.

The final challenge will be to link the different

aspects of the system into a connected whole. These

are the individual’s stories; the game scenario

developed by the teacher; the characters in the game

with their specific animations; and the agents

controlling the characters.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The application of an existing agent cultural

modelling system to a very different culture will

provide both challenges in design and an opportunity

to verify the flexibility of the system. While there

are many aspects of Aboriginal culture that are

related to other cultures, there are also a lot of

different approaches to knowledge sharing which

will be relevant when providing a learning

environment in which users can immerse in the

culture.

We aim to make the learning environment reflect

as many aspects of the culture being learnt as

possible. We will not be using this adaption to make

the player more ‘comfortable’ (Endrass et al, 2011)

as this will not be their own culture they are

experiencing, but we will help them to gain a better

grasp of the subtle differences that arise from a

different value system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by national funds through

FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia,

under project PEst-OE/EEI/LA0021/2011.

Also the Australian Government Office for

Learning and Teaching has provided support for this

project in Australia. The views in this project do not

necessarily reflect the views of the Office.

REFERENCES

Aylett, R. S. Louchart, S., Dias, J., Paiva, A. and Vala. M.,

2005. Fearnot!: an experiment in emergent narrative.

In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer-

Verlag, London, UK, UK 305-316.

Bogdanovych, A. Rodriguez, J. A. Simoff, S. Cohen A.

and Sierra C, 2009. Developing Virtual Heritage

Applications as Normative Multiagent Systems. In

proceedings of the Tenth International Workshop on

Agent Oriented Software Engineering AOSE,

Budapest, Hungary, 10-15 May.

Dias, J. Mascarenhas, S. Paiva A., 2011. FAtiMA

Modular: Towards an Agent Architecture with a

Generic Appraisal Framework. In Workshop in

Standards in Emotion Modeling, Leiden, Netherlands.

Endrass, B, Andre, A, Rehm M, Lipi, A. and Nakano, Y.

2011. Cultural related difference in aspects of

behaviour for virtual characters across Germany and

Japan. Proc 10th Intl Conf on Autonomous Agents and

multi agent systems (AAMAS 2011), pp 441-8.

Hofstede G., 1991. Cultures and Organisations. McGraw-

Hill, London.

Mascarenhas, S., Dias, J, Prada, R. and Paiva, A, 2010. A

dimensional model for cultural behavior in virtual

agents, Applied Artificial Intelligence, 24, pp. 552–

574.

Nazir, A, Lim, M Y, Kriegel, M, Aylett, R, Cawsey, A,

Enz, S, Rizzo, P. and Hall, L, 2008. ORIENT: An

Inter-cultural role-play game. In Proceedings of

Narrative in Interactive Learning Environments 2008

conference NILE, 6-8 Aug 2008, Edinburgh.

Ortony, A., Clore, G., and Collins, A., 1988. The

Cognitive Structure of Emotions. New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Reece, G., Nesbitt, K., Gillard, P., & Donovan, M. (2010).

Identifying cultural design requirements for an

Australian Indigenous website. Proceedings of the

11th Australian User Interface Conference, Brisbane.

Spaniol, M., Cao, Y., Klamma, R., Moreno-Ger, P.,

Fernández-Manjón, B., Sierra, J. L., et al. (2008).

From Story-Telling to Educational Gaming: The

Bamiyan Valley Case. In F. Li, J. Zhao, T. Shih, R.

Lau, Q. Li, & D. McLeod (Eds.), Advances in Web

Based Learning - ICWL 2008: 7th International

Conference Springer, Berlin pp. 253-264.