Local e-Government Transformation

An International Comparison

Stuart Dillon

1

, Eric Deakins

1

, Daniel Beverungen

2,

Thomas Kohlborn

3

,

Sara Hofmann

2

and Michael Räckers

2

1

Department of Management Systems, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

2

Department of Information Systems, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

3

Business Process Management Group, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

Keywords: e-Government, Local Government.

Abstract: Governments have invested vast amounts of time, public money, and effort into technologising and

transforming public sector relationships, with the goal of achieving optimised government service delivery,

governance, and constituency participation. To discover the extent that transformation has actually been

achieved by local government organisations, this paper provides a cross-national comparison of local e-

government effectiveness as judged by internal stakeholders in Australia, Germany, and New Zealand. It

appears that e-government continues to be viewed by the policymakers charged with developing it as

something that supplements, rather than displaces, their traditional government services. Far from being

transformative, only incremental improvements to internal procedures and service quality were reported.

Electronic government (e-government) can be

defined as the transformation of internal and external

public sector relationships through Web-enabled

operations, information technology and

communications, with the aim of achieving

optimised government service delivery, governance,

and constituency participation (Baum, et al., 2000).

Early e-government initiatives were characterised by

rudimentary Web services that pushed information

to citizens, although it soon became clear that newer

e-commerce technologies promised greater

interactions with citizens.

Today it is widely accepted that e-government

can transform public sector relationships through

online services that are user-centred, convenient,

integrated, proactive, inclusive, and efficient. By re-

engineering existing relationship processes with the

aid of computer-based information and

communications technologies (ICT) radical

improvements to the delivery of public services are

being enabled (HMGov, 2005); (Transformation,

2006).

But to what extent has 'transformation' actually

taken place? Has the traditional bureaucratic

paradigm really been replaced by a new e-

government paradigm?

The purpose of the present study was to

determine to what extent e-government initiatives

have actually achieved transformation within the

local government sector. This sector was chosen in

recognition of its unique customer-facing role. In

stark contrast to similar studies the study considered

the impact of e-government from the perspective of

internal stakeholders and aimed to identify issues

associated with the philosophy and implementation

of e-government from the perspective of government

itself.

To increase the likelihood of detecting evidence

of transformative e-government in action, a cross-

national examination of e-Government effectiveness

in Australia, Germany, and New Zealand is

provided. The next section reviews relevant e-

government literature to highlight the research gaps

addressed by the study. The context of the three case

countries is then outlined before the research method

and data collection procedures are described.

Significant findings are then presented and the paper

concludes with a general discussion, limitations and

opportunities for further research.

361

Dillon S., Deakins E., Beverungen D., Kohlborn T., Hofmann S. and Rackers M..

Local e-Government Transformation - An International Comparison.

DOI: 10.5220/0004367803610367

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2013), pages 361-367

ISBN: 978-989-8565-54-9

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Local e-Government

Local e-government is defined as any dependent and

independent geographically defined government

entity that delivers services to citizens online. In

contrast to their central government counterparts,

local authority organisations are more strongly

focused on providing front-line services to citizens.

Developed and developing nations are moving away

from the paradigm of government as a bureaucratic

faceless organisation (Exec, 2003); (King and

Cotterill, 2007); (State Services Commission, 2007)

to one which is responsive; makes extensive use of

ICT; and treats citizens as customers (Ho, 2002);

(Moon, 2002); (Newman et al., 2001).

Although citizen-centric research has increased

our knowledge about user perceptions, the patchy

uptake of many e-government services (Kotamraju

and van der Geest, 2012) makes it imperative to also

understand the policymaker’s perspective.

2.2 e-Government Effectiveness

Given the vast amount of time, public money and

effort that national and local governments have

invested into transforming public sector

relationships with technology (Affisco and Soliman,

2006); (Sarikas and Weerakkody, 2007), e-

government effectiveness has long been a topic of

interest for researchers. Much less common than

studies into the impact of e-government on citizens,

is the view of the policymaker who happens to be

closest to the action and charged with the 'decision,

development and implementation' of e-government

initiatives.

2.3 e-Government in Germany

The German government comprises administrations

at the Federal, State, and Local levels. Authorities at

each level are responsible for different tasks and are

organized in different ways. Similar to Australia and

New Zealand, Germany is a long-time leader in e-

government as demonstrated by its position in the

UN e-government rankings (UN, 2012).

In Germany, the term ‘local government’

actually covers 22 administrative districts, 301

counties, 112 urban municipalities, and 12,234

municipalities (Fuchs, 2009). German local

governments, while they are subject to certain

restrictions, are entitled to administer themselves.

They are free to structure their organization, manage

their human resources, and organize, plan and design

their territory as well as manage their own finances.

The current e-government strategy is laid down in

the 'eGovernment 2.0' programme (eGov, 2006) and

aims to create a fully integrated e-government

landscape throughout all government administration

levels.

2.4 e-Government in Australia

Australia comprises 6 states and 10 territories and its

local government sector comprises some 550

individual bodies and councils (Hearfield and

Dollery, 2009); a number that has been steadily

declining due to amalgamations. Legislation and

control of local government occurs at the state or

territorial level rather than the central (federal) level.

Thus, local councils, which provide various services,

also control local infrastructure.The national portal

(http://australia.gov.au) acts as a one-stop-shop that

connects citizens to the information and services of

around 900 government websites and state and

territory resources. Australia's e-Government

Strategy is laid down in the Australian Public

Service Information and Communications

Technology Strategy 2012 - 2015 (APS, 2012). This

is built on a vision that ’interactions with people,

businesses and the community will occur seamlessly

as part of everyday life.’

2.5 e-Government in New Zealand

In New Zealand, local government is subordinate to

central government (Palmer and Palmer, 2004);

(Tomblin, 2004). Two distinct types of authority

provide local government services: territorial

authorities (city or district councils) and regional

councils. City and district councils are tasked with

providing day-to-day services to their communities.

The current e-Government strategy in New

Zealand is described in 'Enabling Transformation: A

Strategy for E-government 2006' (Transformation,

2006), which reflects recent changes in technology;

particularly the growth in social networking

Research conducted by the authors, including in

New Zealand, has identified significant variations in

the adoption of e-local government in terms of

money and effort expended, and the associated

commitment to widespread adoption of emerging

technologies. (Deakins and Dillon, 2002); (Dillon et

al, 2006)

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

362

3 METHOD

A survey instrument containing qualitative and

quantitative questions was used to gain a cross-

national comparison of e-local government

effectiveness from the perspective of the internal

stakeholders, This was developed by the authors and

used to collect primary data from a convenience

sample of local e-government organisations located

in three countries acknowledged to be high-

performers in e-government terms.

The general form of statements used in the

survey was: "Please indicate, by circling one number

for each statement, the extent to which you would

consider each of the following when developing or

maintaining your web site". Statements were

arranged on a six-point Likert scale.

The German sample comprised e-government

policymakers from the state of North Rhine-

Westphalia, which contains four of Germany's

largest cities and is the most populous state in

Germany (around 18 million citizens). The survey

was translated into German for these respondents

and then verbally checked with other members of

the research team to ensure that the intended

meaning had not been lost. The Australia sample

was confined to the 73 local authorities in the State

of Queensland, which has a population exceeding 4

million people and is the third most populous state in

Australia. The New Zealand sample comprised all

78 local authorities in the country, which together

service a population of some 4.5 million citizens.

In mid-2012 a pilot version of the survey was

revised prior to being sent to specifically targeted

individuals within the selected organisations.

Recipients were guaranteed anonymity and

reminders were issued after two weeks to improve

the response rate. The purpose of the study was

outlined to the recipients, who were requested to

forward the survey to "the person in charge of

website policy and design".

4 FINDINGS

The response rates are shown in Table 1. While the

number of responses from the Australian and

German studies was relatively low, it is judged that

the results are a fair representation of the relevant

issues in those two countries.

Table 1: Survey Response.

Sample

Size

Surveys

Returned

Response

Rate

Australia 73 10 14%

Germany 427 68 16%

New Zealand 78 24 31%

4.1 Demographic Information

A key aim of this study was to detect evidence of

transformative e-government in action by examining

acknowledged leaders in e-government

development. Table 2 summarises relevant

demographic information across the three samples. It

is apparent that a significant proportion of local

authorities in all three countries have fewer than 500

employees (73.5% in Germany, 60% in Australia,

and 83.3% in New Zealand). In both Germany and

Australia, a higher proportion of local authorities

employ more than 1,000 employees.

It is interesting to note that, even though the

average catchment populations of the local

authorities are similar, the New Zealand citizen/staff

ratio is significantly higher. New Zealand

organisations generally tend to be small, with some

97% having 19 or fewer employees (SMEs, 2012).

Also, NZ local authorities do not offer health or

education services thereby requiring fewer staff.

4.2 Development Philosophies

To elicit understanding of the rationale behind local

e-government initiatives, the respondents were asked

to consider the nature of the development

philosophies that underpin e-government projects.

The development philosophy alternatives in Table 3

were presented for consideration.

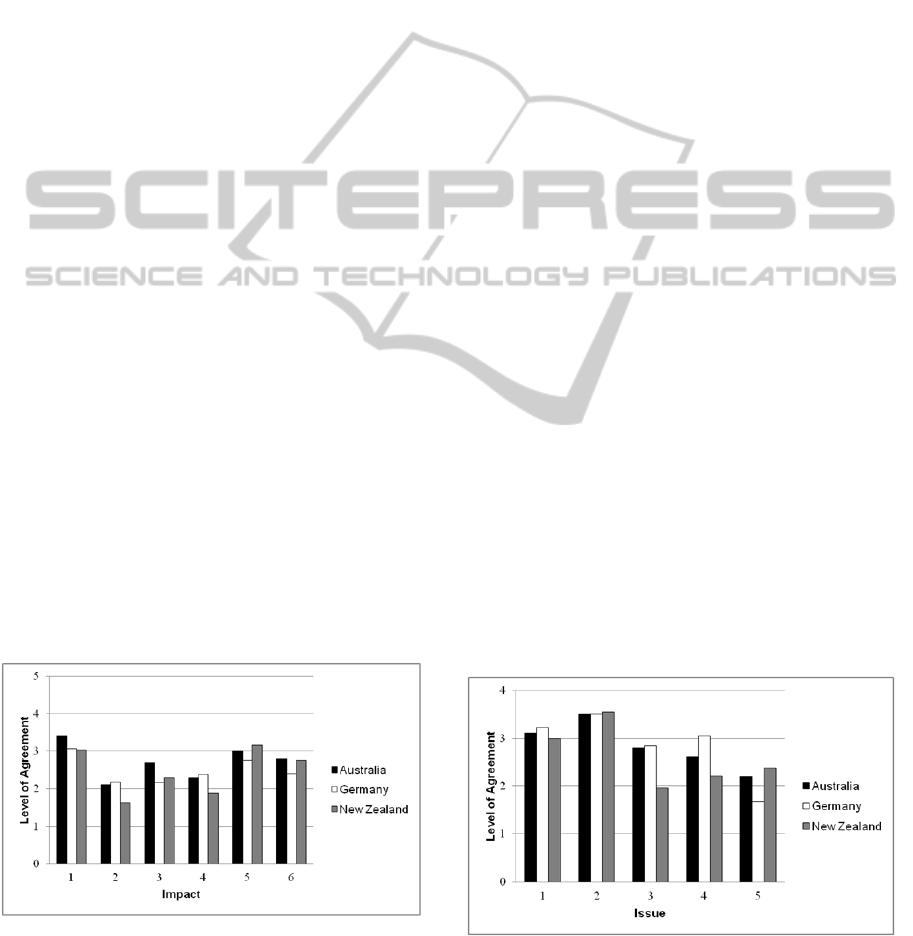

The results shown in Figure 1 relate to the

development philosophies that underpinned e-

government initiatives in the recent past. Similarly,

Figure 2 shows the development philosophies which

are currently driving new e-government initiatives.

Generally-speaking little change is reported

between the development philosophies of the recent

past and what is current. For example, it is

interesting to note that in an era of Web 2.0 services,

that both Australia and New Zealand local

authorities are planning to push even more

information to citizens. This suggests that the old

philosophies are believed to be still relevant and that

a relatively ‘steady as she goes’ strategy is being

played out. This is in line with governments' often

cautious approach to adopting ICT.

Locale-GovernmentTransformation-AnInternationalComparison

363

Table 2: Demographic Information.

UN eGov Index:

World average = 0.4877

* best = 0.9283 Rep. Korea

* worst = 0.0640 Somalia

Country (Rank): Australia (12) Germany (17) New Zealand (13)

UN eGov Index 0.8390 0.8079 0.8381

: Online services 0.8627 0.7516 0.7843

: Telco Infrastructure 0.6543 0.7750 0.7318

: Human capital 1.0000 0.8971 0.9982

(2012 values)

No. % No. % No. %

Number of employees in

organisation

R=10 100 R=68 100 R=24 100

0-99 1 10.0 21 30.9 5 20.8

100-499 5 50.0 29 42.6 15 62.5

500-1,000 1 10.0 7 10.3 2 8.3

>1,000 3 30.0 11 16.2 2 8.3

Average number of

employees

871 - 793 - 361 -

Average catchment

population

115,750 - 75,222 - 91,235 -

Average number of

citizens per employee

133 - 95 - 253 -

Used consultants in last

12 months?

- 60.0 - 33.8 - 54.2

Website spend

(€ per citizen)

This year Next year This year Next year This year Next year

0,07 0,06 0,10 0,17 0,16 0,80

Table 3: Local E-Government Development Philosophie.

1 A website to push information to citizens via

mailing lists

7 A website initiative that recognises the

continued importance of a physical presence

2

Accessibility for ALL citizens

8 A website to provide integrated channels that

satisfy citizens on all fronts

3 A website to provide information in response to

citizen requests

9

Dedicated to the concept of e-democracy

4 A website to provide links to useful information and

services

10 An intention to reduce physical sites and the

electronic operation grows

5 A website as just an extra channel for information &

services

11

Resisting the e-government trend

6 A website to foster collaboration with contractors or

suppliers

12 A website focused on revitalising existing

physical operations

Figure 1: Past Development Philosophies.

Figure 2: Current Development Philosophies.

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

364

To provide more detail on what is being planned,

respondents were quizzed on the importance of a

range of development issues, Table 4. It is

interesting agreement on the top-three ranked issues

(Accessibility to all citizens, System security, and

Operational efficiency). Although not as strongly

expressed, there is also agreement with the lower

ranked issues: with e-tailing, internal cultural

obstacles and private sector partnerships receiving

least consideration. The largest difference concerns

the subject of the digital divide.

A final observation for this section concerns the

average response score expressed by the German

respondents, which was significantly lower than the

corresponding Australian and New Zealand data

values. From examination of the data it is

questionable whether this difference reflects a

systematic cultural difference to professionals

responding to survey questions, which if true would

require some form of standardisation to achieve

comparability.

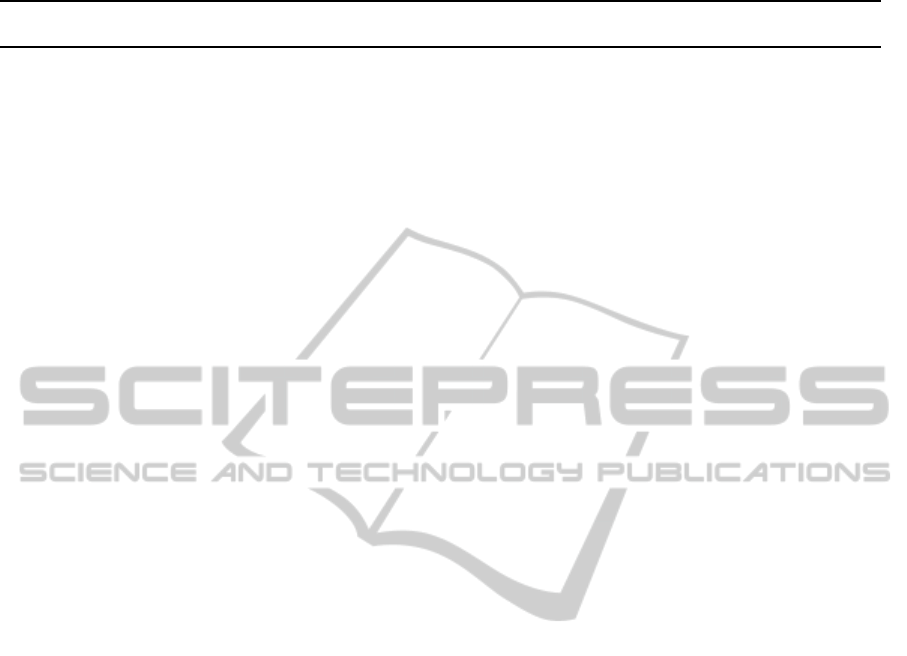

4.3 Impact on the Organisation

To understand the effect of e-government initiatives

on the organisations themselves, six potential

impacts were offered for consideration:

1. Significant improvements in organisational

performance

2. Significant changes to organisational structure

3. Significant changes to roles & responsibilities

4. Significant increase in the number of the services

provided

5. Significant increase in the quality of services

provided

6. Fundamental changes to internal procedures

A reasonable level of consistency across each of the

country responses is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Organisational Impact of e-Government.

Relatively low scores for significant changes to

organisational structure; significant changes to roles

& responsibilities; and significant increases in the

number of services all provide further support that

many local authorities consider e-government as

adding to existing physical operations, rather than a

means of achieving organisational transformation.

Although policymakers expressed higher scores

for having achieved significant improvements in

organisational performance and a significant

increase in the quality of services provided, it would

be interesting to have a comparison with citizens’

perceptions. Overall, it may be concluded that the

results provide little support for the notion that e-

government has been transformational for these

local government organisations.

4.4 Use of Mobile Devices

With a view to understanding future developments,

respondents were asked how well suited were their

e-government initiatives to offering mobile

technologies. Five ‘issue’ statements were offered

for consideration:

1. Using mobile devices would be very easy for all

stakeholders

2. Using mobile devices would be very convenient

for all stakeholders

3. There is too much uncertainty associated with

using mobile devices for local government

transactions

4. Mobile devices are very risky compared with

other ways of transacting

5. Financial transactions using mobile devices are

very secure

Figure 4 indicates strong and consistent support

for policymakers’ belief that mobile devices offer

convenience to citizens and other stakeholders and

would be very easy for all stakeholders. However,

this support is countered by concerns about their

security, particularly for financial transaction.

Figure 4: Potential Use of Mobile Devices.

Locale-GovernmentTransformation-AnInternationalComparison

365

Table 4: Development Issues.

German local authorities appear to have least

confidence, which is worthy of further investigation

since it is unclear whether they are naturally risk

averse or have more knowledge of security matters.

In contrast, New Zealand respondents appear to

be much more positive about transacting with

mobile devices, which may reflect both the country's

relative isolation and its recent ranking as the least

corrupt and the best country in the world in which to

conduct business (Forbes, 2012).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Many authors have foreshadowed the

transformational effects of information technology

on government, indicating that it that will offer

improved access and delivery of information

services to citizens, business partners, public sector

employees, and other governments, agencies and

entities (e,g., Affisco and Soliman, 2006); (Baum, et

al., 2000); (Ho, 2002); (Shan., et al., 2011).

The purpose of this research was to determine

the extent that government transformation has

actually been achieved by local government

organisations. To this end, it compared and

contrasted the views of local government

policymakers in Australia, Germany, and New

Zealand regarding their own e-government

initiatives and how the organisation has been

impacted. Changes in attitude were also assessed.

In spite of the fact that acknowledged 'world e-

government development leaders' were targeted, it

appears in general that contemporary information

communication technology is merely viewed as a

convenient means of supplementing traditional

government services. This has resulted in only

incremental improvements to service quality, if

compared against what is foretold. Furthermore,

given the continued lack of support for radical

changes to be made to traditional government

processes, it is unlikely that any deep-seated

transformation will happen any time soon.

These findings are only tentative since the main

limitation of this study is its failure to achieve a 100

percent response rate. This gave an incomplete

summary of the views of local authority policy

makers in each of the countries sampled. A broader

sample of exemplar countries is also desirable.

Opportunities for further research were noted in

the paper. In particular, a deeper understanding of

the factors inhibiting transformation is needed in

view of the vast amounts of time, public money and

effort currently being expended on e-government

initiatives around the world.

Germany Australia New Zealand

Characteristic Average Rank Average Rank Average Rank

Accessibility to all citizens 4.52 1 4.70 2= 4.54 3

Local tax collection 2.09 13 2.00 15= 2.58 13

System security 4.34 2 4.80 1 4.58 2

Operational efficiency 3.88 3 4.70 2= 4.63 1

E-tailing 1.35 16 2.00 15= 1.88 16

Internal cultural obstacles 1.81 15 3.20 12 3.30 11

The digital divide 1.98 14 3.30 11 3.71 9

Citizen privacy 3.58 7 4.50 5 4.38 4

E-business/e-government

legislation

3.62 6 4.60 4 3.92 8

Citizen confidence with local

government

3.49 8 4.30 6 4.09 6

Internal IT workforce capability 3.75 4 3.90 9= 4.21 5

Needs of minority groups 3.11 9 3.90 9= 3.63 10

Private sector partnerships 2.33 10 2.40 14 2.29 15

Citizen trust of local

government

3.70 5 4.20 7 3.96 7

Intended and unintended social

effects on citizens

2.11 12 4.00 8 3.08 12

E-procurement 2.19 11 3.00 13 2.38 14

Average score

2.99 3.72 3.57

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

366

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the German Federal

Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF),

promotion sign APR 10/805.

REFERENCES

Affisco, J. F. and Soliman, K. S. (2006). E-government: a

strategic operations management framework for

service delivery. Business Process Management

Journal, 12(1) 13-21.

APS. (2012). Australian Public Service Information and

Communications Technology Strategy 2012 - 2015,

Copyright Australian Government,

http://www.finance.gov.au/publications/ict_strategy_2

012_2015/docs/APS_ICT_Strategy.pdf, Retrieved 21

January 2013.

Baum, C., Di Maio, A., and Caldwell, F. (2000). What is

eGovernment. Gartner’s definitions, Research Note

(TU-11-6474).

Deakins, E., & Dillon, S. M. (2002). E-government in

New Zealand: the local authority

perspective, International Journal of Public Sector

Management, 15(5), 375-398.

Dillon, S., Deakins, E., & Chen, W. J. (2006). e-local

government in New Zealand: The shifting policymaker

view. The Electronic Journal of e-Government, 4(1),

9-18.

eGov (2006). German Federal Ministry of the Interior,

http://www.verwaltung-

innovativ.de/cln_117/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/

1125281__english__version__egovernment__2__0,te

mplateId=raw,property=publicationFile.pdf/1125281_

english_version_egovernment_2_0.pdf, Retrieved 21

January, 2013.

Exec (2003) Executive Office of the President of the

United States, “Implementing the President’s

Management Agenda for E-Government: E-

Government Strategy”, [online],

http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/egov/2003egov_strat

.pdf

Forbes. (2012). Best Countries For Business 2012,

http://www.forbes.com/best-countries-for-business/,

Retrieved 31 January, 2013.

Fuchs. (2009). Ein Wertschöpfungsnetz für die öffentliche

Verwaltung - Unterstützung des einheitlichen

Ansprechpartners im Rahmen der EU-

Dienstleistungsrichtlinie, Dissertation, Universität

Münster, Berlin.

Hearfield, C. and Dollery, B.E. (2009). Representative

democracy in Australian local government,

Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 2, 61-

75.

HMGov. (2005). " Transformational government: enabled

by technology, http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/

media/141734/transgov-strategy.pdf, Retrieved 21

January 2013.

Ho, A.T. (2002). Reinventing Local Governments and the

E-Government Initiative, Public Administration

Review, 64(4), 434-443.

King, S. and Cotterill, S. (2007). “Transformational

Government? The Role of Information Technology in

Delivering Citizen-Centric Local Public Services”,

Local Government Studies, 33(3), 333.

Kotamraju, N. P., and van der Geest, T. M. (2012). The

tension between user-centred design and e-government

services. Behaviour & Information Technology, 31(3),

261-273.

Moon, M. J. (2002) “The Evolution of E-Government

Among Municipalities: Rhetoric or Reality?” Public

Administration Review, 62(4), 424-433.

Newman, J., Raine, J. and Skelcher, C. (2001).

“Transforming local government: Innovation and

modernization”, Public Money and Management.

Palmer, G. and Palmer, M. (2004). Unbridled Power: New

Zealand’s Constitution and Government, Oxford

University Press, Melbourne.

Sarikas, O. D. and Weerakkody, V. (2007). Realising

integrated e-government services: a UK local

government perspective. Transforming Government:

People, Process and Policy, 1(2), 153-173.

Shan, S., Wang, L., Wang, J., Hao, Y., and Hua, F. (2011).

Research on e-Government evaluation model based on

the principal component analysis. Information

Technology and Management, 12(2), 173-185.

State Services Commission. (2007). “E-Government in

New Zealand”, [online], http://www.e.govt.nz/

SMEs. (2012). Small and Medium Businesses in New

Zealand; Report of the Small Business Advisory

Group, http://www.med.govt.nz/business/business-

growth-internationalisation/pdf-docs-library/small-

and-medium-sized-enterprises/small-business-

development-group/previous-sbag-reports/small-

medium-businesses-in-nz-apr-2012.pdf, Retrieved 21

January 2013.

Tomblin, E.E. (2004). Local Government and the

Constitution: Protecting Local Autonomy and Local

Democracy, Law Faculty, Victoria University of

Wellington, Wellington.

Transformation. (2006). Enabling Transformation: a

Strategy for e-government 2006, New Zealand State

Services Commission, http://archive.ict.govt.nz/

plone/archive/about-egovt/strategy/, Retrieved 21

January 2013.

UN. (2012). United Nations E-Government Survey.

http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/document

s/un/unpan048065.pdf, Retrieved 12 November 2012.

Locale-GovernmentTransformation-AnInternationalComparison

367