Self-other Agreement on Influence Attempts in Virtual Organizations

Do Agents and Peers See Eye to Eye?

Henning Staar

1

and Monique Janneck

2

1

Department of Psychology, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

2

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Luebeck University of Applied Sciences, Luebeck, Germany

Keywords: Influence Tactics, Micro-politics, Self-other Agreement, Virtual Organizations.

Abstract: The aim of the study was to determine the convergent and discriminant validity of self-peer reports from

three different sources on the use of influence tactics in virtual organizations. Therefore, directly related

triads of network members were analyzed. First, members (agents) should describe how they try to

influence a certain person (target) in the joint collaboration. Second, the defined target and another network

member (non-target) described how they perceive the agent’s influence attempts. All sources rated nine

types of influence tactics. The resulting multitrait-multimethod design was analyzed with 243 sets of triads

using structural equation modeling (SEM). Results supported evidence for convergence of agents’ and

peers’ reports on influence attempts and confirmed the multidimensionality of micro-political behavior in

virtual organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, factors such as globalization

and technological advancements have led to new

organizational structures. Most notably, several

forms of virtual organizations and networks have

emerged as possible solutions to these new

challenges. However, little is known about social

influence processes between individual members of

virtual networks (Elron and Vigoda-Gadot, 2006),

especially when influence is mediated through an

expanding variety of information and

communication technologies (ICT) that separate the

parties spatially and/or temporally (Barry & Fulmer,

2004). In ‘traditional’ managerial settings such

mutual influence processes–often referred to as

micro-politics–have been acknowledged as being “a

pervasive aspect of organizational life” (Blickle,

2003, p. 40). Given the lack of established

leadership theories in virtual organizational settings,

influence tactics can thus be viewed as a ‘vital tool’

for members to get their way in network issues

(Greer and Jehn, 2009).

However, current empirical findings on social

influence processes in virtual collaboration setting

solely rely on self-rating scales. Thereby,

respondents are asked to evaluate the use of several

influence strategies when trying to achieve their

aims within the network. As a result, the insights

into micro-political behavior in virtual networks

have been limited so far to the actor’s perspective.

Consequently, it remains unclear whether micro-

political agents actually manage to create the image

that they seek when interacting with their network

partners via ICT. According to this, influence targets

could have a totally different account of what

happens when an agent tries to cause him or her to

do something. Therefore, the purpose of the present

study was to evaluate the convergence of agents’

and peers’ reports on micro-political influence

attempts in virtual networks.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Virtual Networks

There is a wide variety of forms that are embraced

by the term ‘virtual organizations’ (Travica, 2005).

However, the wide majority of definitions agree that

virtual organizations are forms of “inter-

organizational, cross-border ICT-enabled

collaboration between legally independent entities,

usually with a specific economic goal” (Pitt,

Kamara, Sergot and Artikis, 2005, p. 373).

Especially horizontal forms of collaboration are

551

Staar H. and Janneck M..

Self-other Agreement on Influence Attempts in Virtual Organizations - Do Agents and Peers See Eye to Eye?.

DOI: 10.5220/0004495505510560

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (STDIS-2013), pages 551-560

ISBN: 978-989-8565-54-9

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

important for freelancers or small and medium-sized

enterprises that might be in danger of losing their

competitiveness in a globalized market. However, at

the same time, network members often still act as

individual competitors on the market and as such are

caught between cooperation and competition–a

potential field of conflict which has also been

labeled as ‘coopetition’. Beyond that, most virtual

organizations can be described as being polycentric,

i.e., highly distributed through loosely coupled

associations with high degrees of autonomy of their

members, brought together through intense use of

ICT (e.g., Travica, 2005).

2.2 Micro-politics

Given the lack of formal hierarchies and roles as

well as a distributed leadership over distance, it is

sensible to assume that informal actions of

individual network members play a crucial role in

shaping and governing the network. In

organizational science, so-called micro-political

processes are understood as strategies of individuals

to achieve their goals, realize ideas, or push certain

interests (e.g. Yukl and Falbe 1990). In their

research, Janneck & Staar (2011) have identified a

number of typical informal behavioral patterns–so-

called micro-political tactics–being used in virtual

organizations (table 1).

An important differentiation among these tactics

aims at their range of influence. The first six tactics

are more or less restricted to dyadic influence

attempts, i.e., an agent is attempting to directly

influence a certain target person in a given

interpersonal setting. This dyadic perspective on

social influence in virtual settings has been prevalent

so far (e.g., Barry & Fulmer, 2004). However,

beside direct dyadic relations of inter-personal

influence, some authors have emphasized the

importance of indirect structural tactics. These are

related to the individual’s position within the

network as a whole rather than on mere influence

dyads. In their set of tactics, Janneck & Staar (2011)

have considered Mediating, Proactive Behavior and

Visibility as indirect attempts to gain influence.

Former research on political processes in virtual

organizations suggests that technology-based

interactions may be especially susceptible to

informal influence processes (Wilson, 2003).

Moreover, ICT used by inter-organizational

networks might not only contribute to but even

constitute micro-political processes, as technology

serves both: making existing processes and

structures more explicit and bringing forth new roles

Table 1: Micro-political tactics in virtual organizations.

Direct tactics

Rational

Persuasion

Spreading information to the network

partner(s) to clarify one’s concerns.

Assertiveness

Engaging in open confrontation with

or putting pressure on the network

partner(s).

Exchange

Offering to do a network partner a

favour in return; Signalising to

reciprocate for the network partner’s

support

Inspirational

Appeals

Calling upon the common vision, the

basic idea of a network; emphasizing

the need to pull together for being

successful.

Self-Promotion

Emphasizing one’s efforts regarding

the network collaboration or one’s

value for the network.

Inspiring Trust

Trying to appear open-minded about

the network partners’ concerns;

purposefully presenting oneself as a

network partner who is willing to share

information and resources.

Indirect tactics

Visibility

Trying to show presence via electronic

media; Purposefully using all available

channels to call attention to one’s

concerns.

Proactive

Behavior

Looking for opportunities to play an

additional part in the network beyond

the primary role; taking over new tasks

and/or roles within the network to

extend one’s scope of action.

Mediating

Trying to mediate between partners

during negotiations and discussions;

Keeping a non-committed position in

discussions and controversies instead

of taking sides with a party straight

away.

and rules (Janneck and Staar, 2011). However, these

relations remain artificial if the targets’ perceptions

of influence attempts are not evaluated in relation to

the agent’s original intention.

2.3 Agent-target Convergence

Focusing on intra-organizational influence attempts,

some studies have examined the convergence of

agents’ and targets’ reports. In summary, most

results confirm significant agent-target convergence,

albeit only at a moderate level (for an overview, see

Blickle, 2003). The development of new

organizational settings such as virtual organizations

rises the question whether technology-based

interaction has an effect on processing and

understanding of interpersonal influence (Okdie and

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

552

Guadagno, 2008; Wilson, 2003). Whereas in

‘traditional’ intra-organizational face-to-face

interaction, influence agent and target(s) share the

same physical location, can see and hear one

another, receive messages in real time as they are

produced, and send and receive information

simultaneously and in sequence, this is seldom the

case for distributed parties as in virtual

organizations. So far, empirical micro-political

research on self-peer agreement in intra-

organizational and industrial settings has been

reduced to same time same place conditions

(Blickle, 2003). Few research attention has been

paid to the question of how technology-mediated

interaction affects the targets’ perception of an

agent’s influence attempts (Barry and Fulmer,

2004).

Based on the premises of Social Impact Theory

(Latané et al., 1996), some authors have suggested

that the impact of influence on a target decreases

with increasing distance (e.g., Elron and Vigoda-

Gadot, 2006). Similar arguments come from

Driskell, Radtke and Salas (2003) who conclude that

in virtual settings the opportunity for political agents

to transmit, and for targets to access the subtlety,

nuance, connotation inherent in interpersonal

influence messages would be rather low as they do

not experience “the immediacy of interacting and

being involved with a physically present team

member” (Driskell et al., 2003, p. 298). Similarly,

Greer and Jehn (2009) suppose that in computer-

mediated communication (CMC) or other leaner

mediums than face-to-face, traditional non-verbal

clues within influence attempts may not be as easily

captured.

Some researchers reply that conversation via ICT

does not significantly disrupt conversational control

and understanding. From an agent’s perspective,

Abele (2011) notes that ICT-mediated interactions

offer much more opportunities for deliberative

action. Similarly, Okdie et al. (2011) point out that

individuals interacting via CMC “have time to

rethink, edit, and possibly censure the information

they convey to their interaction partners ensuring

they are perceived the way they intend” (p. 154).

Finally, most research agrees that virtual contexts

tend to make people feel free to express themselves

in a manner decoupled from traditional social mores

and restrictions leading to more uninhibited behavior

(Tidwell and Walther, 2002).

Based on the theoretical discussion above, the

following conclusions emerge. So far, the vast

majority of studies that have evaluated micro-

political influence in virtual organizations offer a

restricted perspective, namely that from an agent’s

view. However, neglecting the target’s (or more

general: peer’s) perception of an agent’s behavior,

only a fragmented extract of social influence

processes within these settings can be expected. In

addition, it has become clear that research on

influence behavior in virtual networks should go

beyond mere dyads of inter-personal influence

situations: In most virtual organizations members

are not only loosely connected with each other but

they rather build a tight network of mutual relations.

Accordingly, some influence tactics might not be

restricted to a single chosen target but address the

network and its members as a whole. As a

consequence, for a reliable examination of the

convergent and discriminant validity of agents’ and

peers’ reports on direct and indirect micro-political

influence attempts, real groups of agents, targets and

non-targets as well as parallel scales are needed. In

this study, we will examine self-other agreement of

nine influence tactics used in virtual networks.

3 METHOD

3.1 Subjects

Participants were acquired by means of a systematic

internet research or through online business

platforms such as XING. All persons were asked if

they would care to participate in a study on

communication and cooperation in virtual networks.

As an incentive to participate in the study, all

members were offered an analysis of the age

structure of their network. Furthermore, we raffled

small gifts such as ipods and guaranteed a report on

the results of the study.

Since convergence between different raters

should be analyzed using Structural Equation

Modeling (SEM), a sample size of at least 200

complete sets was needed. Following Marsh, Ballah

and MacDonald (1988), this sample size is necessary

for a meaningful interpretation of the models’ fit-

indices. For this study, a total of 243 complete sets

consisting of agent-target-non-target-triads could be

acquired. The vast majority of respondents worked

as freelancers with a lot of experience in virtual

working being reflected in an average network

membership of more than one year. More than half

of the networks had less than 10 members (55%),

31% had 10-20 members, and 14% had more than

20 members. Most respondents were male (73%),

mean age was 38,8 years. The respondents worked

mainly in Media (36%) or IT (30%) business, 21%

Self-otherAgreementonInfluenceAttemptsinVirtualOrganizations-DoAgentsandPeersSeeEyetoEye?

553

worked in the Health sector (13% other).

Concerning the degree of virtuality, i.e., the

frequency and variety of ICT-usage, the sample was

homogenous: All triads reported to interact first and

foremost via different ICT. Further, network-

exclusive or open groupware were used in most

cases and served as the linchpin to mutual

interactions.

3.2 Research Design

First, members of virtual networks were asked with

whom they were currently working on a common

project and had interacted regularly for the last

months. Without knowing about the study’s focus on

influence, participants should list at least three

persons belonging to their virtual network. As most

of the data was assessed via online questionnaires,

we were able to benefit from dynamically generated

contents. To avoid systematic effects such as

sympathy, one of the listed network partners was

chosen randomly. Then the questionnaire consisting

of the nine influence tactics was presented in

randomized order and the participants (agents) were

requested to rate their own influencing attempts on

the person chosen (target). After completing the

questionnaire, the agents were asked to distribute

two links (that led to a parallel version of the agent’s

questionnaire) which should be sent to the target

person and a further network member (non-target)

who was randomly chosen out of the list of partners

put together by the agent at the beginning. To collect

matched triads of agents, targets and non-targets, a

code was generated at the end of the agent’s

questionnaire, which should be sent to the target and

non-target. When targets and non-targets

participated, they were asked to describe to which

degree the identified agent uses certain types of

influence attempts in an effort to influence the target

(or the peer respectively). After both peers had

finalized their questionnaires, their ratings were

matched with the agents’ questionnaires through the

common code numbers.

One approach to methodically determine the

convergent and discriminant validity of agents’,

targets’ and non-targets’ reports on different micro-

political tactics can be found within the framework

of a multitrait-multimethod (MTMM) design by

which multiple traits are measured by multiple

methods.

Generally, traits are defined as hypothetical

constructs that relate to stable characteristics such as

personality attributes. Methods refer to multiple test

forms or specific measurement methods (Byrne,

2011). However, MTMM-designs have been applied

not only to traits but to influence tactics as well (e.g.,

Blickle, 2003). Further, treating different raters

(such as self-report or specific informants) as

method factors has become a common modification,

too.

In the seminal work of Campbell and Fiske

(1995), the inspection of the correlation matrices of

scores from all variables was analyzed to determine

convergent and discriminant validity. Alternatively,

confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) offer a more

systematic way to deal with multitrait-multimethod

matrices. Especially the Correlated Traits

Correlated Methods (CTCM) approach to MTMM

data has been used as the most widely alternative to

the ‘informal’ approach of analyzing MTMM

matrices. This is particularly attractive because the

model’s structure directly corresponds to Campbell

and Fiske’s original conceptualization of the

MTMM matrix. The CTCM-model offers separate

trait and method factors that are assumed to be freely

correlated, but trait factors are assumed to be

independent of method factors. The rationale behind

this model is that high loadings on trait factors

would suggest convergent validity; high loadings on

the method factors would indicate common method

effects, and moderate correlations among different

trait factors would support evidence of discriminant

validity (Kline, 2005).

The basic CTCM-model was specified as

follows: First, three latent method factors were

defined, i.e., self-, target- and non-target-ratings.

Each of the latent method factors had nine

indicators, i.e., the ratings of the nine influence

tactic scales. In addition, nine latent trait factors

were formulated, representing the ratings of

influence tactics with three indicators each. To test

the models, maximum likelihood estimates were

applied. AMOS 6 was used for calculations.

3.3 Instruments

Influence tactics were measured with an inventory

that captured the nine tactics based on the work from

(Janneck and Staar, 2011, see table A.1 in the

appendix). The original version was used for agent

respondents. Targets and non-targets were given a

slightly adjusted version to assess the agent’s tactical

behavior from three different views. In the agent

version the respondent rated his or her own

influence attempts on the defined target (e.g., “I use

rational arguments to convince [name of the

target]”). The target, in turn, was asked to evaluate

the agent’s use of influence tactics when trying to

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

554

cause him or her to do something (e.g., “[Name of

the agent] uses rational arguments to convince me”).

Finally, the non-target version contained a global

peer view on the agent’s influence behavior in

network issues (e.g., “[Name of the agent] uses

rational arguments to convince his network

partners”). The 6-point-likert scale ranged from 1 =

“never” to 6 = “always”. As a filtering question,

agents were first asked if they were part of a for-

profit network in which projects are realized in

cooperation with other people from the same branch.

Furthermore, all participants were asked to indicate

their sex, age, educational level and actual

profession. Additionally, all members were asked to

indicate network-specific data such as the name,

size, length of cooperation and branch of their

virtual network.

4 RESULTS

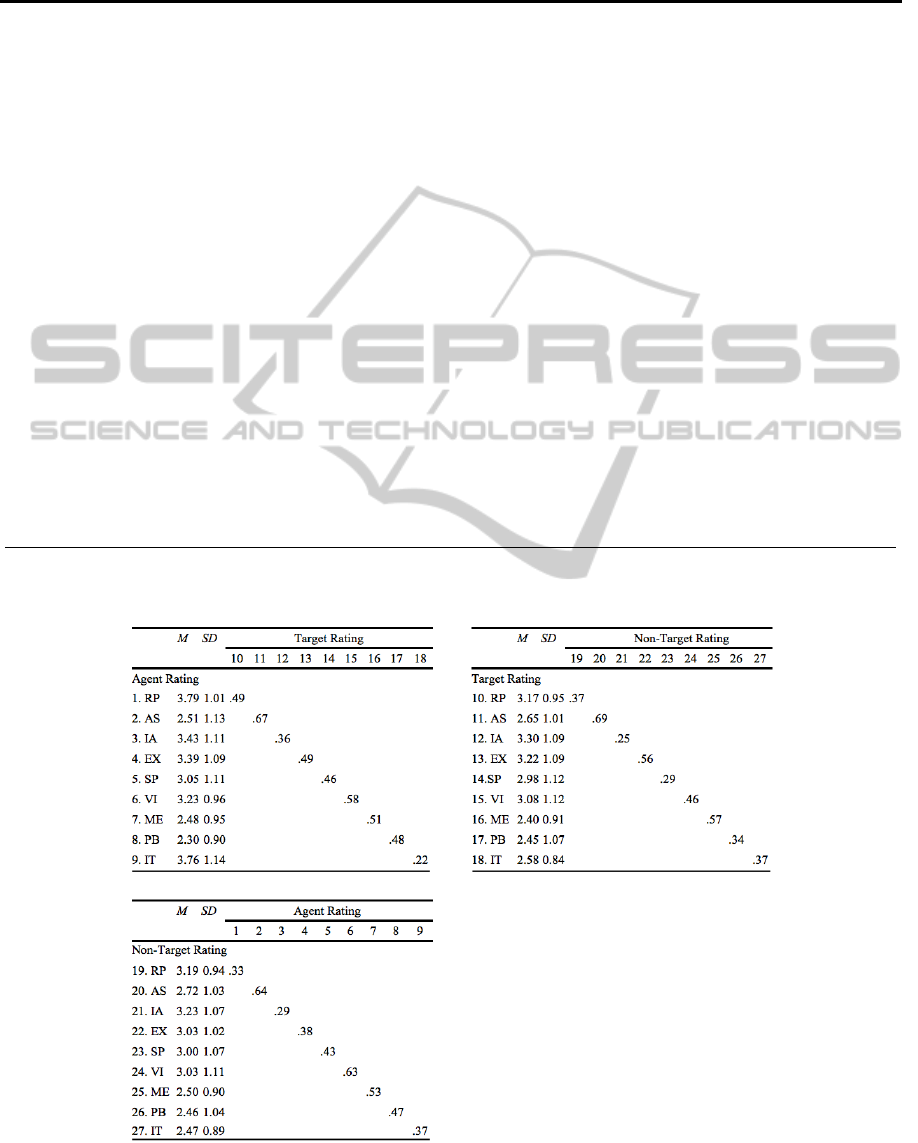

The agent-target-non-target correlation matrices as

well as the scale means, standard deviations and

reliabilities are documented in table A.2 (see

appendix).

Table 2: Parameter Estimates for Model 1 (CTCM) (n = 243): Tactic and Source Loadings.

a

RP AS IA EX SP VI ME PB IT AR TR NR

Agent Rating (AR)

Rational Persuasion (RP) .63* .23*

Assertiveness (AS) .85* .44*

Inspirational Appeals (IA) .93* .17*

Exchange (EX) .60* -.02

Self-Promotion (SP) .78* .10

Visibility (VI) .86* -.10

Mediating (ME) .68* -.09

Proactive Behavior (PB) .92* .20*

Inspiring Trust (IT) .65* .01

Target Rating (TR)

Rational Persuasion (RP) .69* .20*

Assertiveness (AS) .94* -.04

Inspirational Appeals (IA) .38* .27*

Exchange (EX) .82* -.08

Self-Promotion (SP) .59* -.03

Visibility (VI) .66* .24*

Mediating (ME) .77* .09

Proactive Behavior (PB) .52* -.06

Inspiring Trust (IT) .36* .48*

Non-Target Rating (NR)

Rational Persuasion (RP) .49* .20*

Assertiveness (AS) .73* -.11

Inspirational Appeals (IA) .32* -.11

Exchange (EX) .69* .34*

Self-Promotion (SP) .55* .27*

Visibility (VI) .72* .24*

Mediating (ME) .75* -.09

Proactive Behavior (PB) .48* -.13

Inspiring Trust (IT) .57* .21*

Note.

a

Standardized estimates; *

p < .05.

Self-otherAgreementonInfluenceAttemptsinVirtualOrganizations-DoAgentsandPeersSeeEyetoEye?

555

4.1 Goodness of Tested Models

To test the convergent validity of the different

source ratings from agents, targets and non-targets

on nine influence tactics, four structural equation

models were calculated. Following Byrne (2011),

we included the CTCM-model as the general CFA

model and additionally specified two nested models.

Model 2 was specified without method factors but

with correlated traits (CT), Model 3 differed from

Model 1 only in the absence of correlations among

method factors (CTUM). Following Byrne’s

recommendations, the set of models was completed

with the CU-model (Correlated Uniqueness).

The goodness-of-fit indices show that Model 1

yields an acceptable global fit (χ

2

(259) = 342,139, p

= .057). Furthermore, relevant fit-indices such as

CFI (.942) and RMSEA (.039) revealed a good fit to

the data, too (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Similar estimates

were found for Model 3. In contrast, goodness-of-fit

indices for the CU-model proved to be

comparatively poor (χ

2

(180) = 263.109, p = .025;

CFI = .942; RMSEA = .046), Model 2 revealed an

even worse fit. On the whole, the stable solution and

acceptable fit indices of Model 1 support a tenability

of this model. Accordingly, we will focus on this

general CFA-model in the subsequent analyses.

4.2 Analysis of Convergent

and Discriminant Validity

An assessment of self-other agreement on different

tactics can be ascertained by analyzing the

individual parameter estimates. Specifically, the

factor loadings and factor correlations of Model 1

provide the focus here. The completely standardized

estimates for the factor loadings are summarized in

Table 2. Trait and method factor correlations can be

found in Table 3.

In examining these individual parameters,

convergent validity is reflected in the magnitude of

the trait loadings. As Table 2 shows, all trait

loadings are statistically significant with magnitudes

ranging from .315 (non-target-ratings of

Inspirational Appeals) to .944 (target-ratings of

Assertiveness). Moreover, when comparing factor

loadings across traits and methods, it becomes clear

that the proportion of trait

variance exceeds that of

method variance for all but one of the target-ratings

(Inspiring Trust). This means that in the evaluation

of all nine tactics agents’, targets’ and non-targets’

reports converged to a considerable degree.

Beside the basic confirmation of the assumptions

made, a more in-depth examination at the individual

parameter level reveals that some of the trait

loadings are significant indeed but the explained

variances tend to be rather low on a considerable

Table 3: Trait (Tactic) and Method (Source) Factor Correlations for Model 1 (CTCM).

a

Tactics Sources

Measures RP AS IA EX SP VI ME PB IT AR TR NR

Rational Persuasion (RP) 1.00

Assertiveness (AS) -.21* 1.00

Inspirational Appeals (IA) -.11* -.08* 1.00

Exchange (EX) -.19* -.10* -.02* 1.00

Self-Promotion (SP) -.05* -.20* .17* -.06 1.00

Visibility (VI) --.32* -.04* -.05* -.04 .03* 1.00

Mediating (ME) -.13* -.11** -.14*-.08 -.03*-.02* 1.00

Proactive Behavior (PB) -.09* -.08* -.13*-.01 -.04* .35* -.03 1.00

Inspiring Trust (IT) -.08* -.18* -.13*-.13 .04 .16* -.13*-.13* 1.00

Agent Rating (AR) 1.00

Target Rating (TR) .39* 1.00

N

on-Target Rating (NR) .36* .14 1.00

Note.

a

Standardized estimates; *

(p < .05).

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

556

number of trait loadings. Finally, correlations among

trait factors provide an evaluation of the

distinctiveness of self-other agreement and of the

multidimensionality of micro-political behavior.

Most latent trait factors correspond only to a low

degree. Rational Persuasion yields significant

correlations with Visibility (r = .32, p < .05) and

Assertiveness (r = -.21, p < .05). The latter, in turn,

is negatively related to Self-Promotion (r = -.20, p <

.05), and Proactive Behavior correlates with

Visibility at r = .35 (p < .05). In total, these results

support evidence for discriminant validity and the

multidimensionality of micro-political-behavior.

An examination of method factor correlations

reveals significant correlations between agent-

ratings and target-ratings (r = .39, p < .05) and non-

target ratings (r = .36, p < .05) respectively, which

detracts from a discriminability of methods. Possible

explanations for these findings will be discussed

below.

5 DISCUSSION

Do micro-political agents reach to create the image

that they seek when interacting with their partners in

virtual organizations? Or do peers with whom the

agent is interacting rather have a totally different

account of how the agent is trying to exert

influence? To find answers, the aim of the present

study was to determine the convergent and

discriminant validity of agents’ and peers’ reports on

influence attempts in virtual network settings. We

wanted to know whether agents, targets and non-

targets as three different sources are on the same line

when evaluating the agents’ influence attempts in

form of nine micro-political tactics. Despite the fact,

that the main focus was set on convergence, and

hypotheses were formulated according to that effect,

the MTMM-model accounted for the evaluation of

discriminant validity, too, i.e., the extent to which

independent sources diverge in their measurement of

different tactics (cf. Byrne, 2011).

On the whole, the results support the convergent

as well as the discriminant validity of the inventory

being used in the present study. All trait loadings

showed significant estimations, most of them of

considerable magnitude. Moreover, beside high trait

loadings, almost all loadings on method factors were

marginal. In addition, correlations among trait

factors were mainly low. These findings support

strong evidence for a discriminability of the nine

tactics. Interestingly, contrary to our implicit

assumptions, there was no big difference between

the targets’ and non-targets’ ability to perceive direct

influence tactics.

Two conclusions can be drawn from these

results. The first explanation follows from the

ongoing discussion concerning an agent’s influence

style. On that note, some researchers argue that

agents are far from being ‘micro-political

chameleons’, which adjust their influence strategies

to a respective person or situation (cf. Ferris et al.,

2002). Rather, an agent’s choice of tactics appears to

vary only within a certain corridor when attempting

to influence different targets (cf. Barbuto and Moss,

2006). Following the perspective of a relatively

stable inter-individual influence style, convergence

not only between agent and a specific target can be

expected. The rationale behind this view can be

explained through the fact that although non-targets

were not the direct aim of influence within the

present study’s design, they rated their own

experiences with the agent's behaviors, therewith

producing a second ‘target rating’. In doing so, he or

she could have drawn upon recurrent actions of the

agent that are similar to the target’s perceptions.

Another explanation for the convergence of all

three sources on direct influence tactics might be

found in the ‘open playground’ available when

groupware is used. If ICT guarantee an open

information flow between all network members, the

model of dyadic influence attempts might become

ineffective and obsolete. By using open groupware

strategically the whole network can be addressed

simultaneously. Therefore, convergence between all

three parties could have emerged through such a

‘glass-house-effect’. However, we did not control

for the communication channels that were used.

Accordingly, we were not able to differentiate

between influence situations where open forms of

ICT where used vs. those where communication was

masked to others and only certain persons were

addressed (e.g., through e-mail use). This aspect will

be further critically reviewed below.

Compared to most deflating results from intra-

organizational research where agents and targets

meet same time, same place the convergence of

different sources that we have found in virtual

settings can be interpreted as fairly good. How can

this be understood? Some studies on self-other

agreement in personality judgments have shown that

virtual groups were better able to selectively present

aspects of themselves and could better manage their

self-presentation via CMC than those who were

engaged in physical face-to-face interactions (Okdie

et al., 2011). In addition, social and normative

contexts may be of even greater importance in

Self-otherAgreementonInfluenceAttemptsinVirtualOrganizations-DoAgentsandPeersSeeEyetoEye?

557

virtual organizations when compared to intra-

organizational face-to-face interactions. For

example, it can be assumed that the negotiation of

norms and the evaluation of the persons’ network fit

are of more substantial importance in virtual

organizations as in traditional industrial settings.

Especially when formalized routines are missing, the

networks’ members have to rely on a common sense

in their decisions about the persons they want to

work with. Before de facto collaboration occurs,

potential partners have put each other to the test in

terms of trust, engagement, and the others’

willingness to reciprocity. Accordingly, it is

reasonable to assume that most of the members in

virtual organizations know each other very well,

which would provide an explanation for high self-

peer-agreements. Even if information available via

ICT is fragmented, incomplete, or ambiguous,

perceivers can resort to their previous knowledge of

each other.

A more in-depth view to the results, however,

reveals some shortcomings of the tested model.

Almost half of the error variances that were

specified in the CTCM-model were of considerable

height. Within error variances, ‘the rest of the world’

can be found which is not explained through

specified trait or method factors. It can be assumed

that additional variables which had not been

specified within this model may be of crucial

importance to better understand the model’s

interrelations. One important factor could lie in the

variety of ICT used within the participants’ virtual

organizations. As mentioned in the description of the

sample, the vast majority of triads used a wide

variety of ICT to coordinate workflows and to

communicate with each other. As we have

mentioned above, we did not further differentiate

with respect to media usage. Nevertheless, it is

obvious that some mediating technologies may be

more effective for some kinds of tasks than others.

Therefore, situational and contextual factors created

through different communication media are likely to

affect the selection of influence strategies as well as

the peers’ interpretation of the actors’ behavior

(Sussman et al., 2002). Therefore, future research

should take a closer look on how and for what

purposes the teams’ technologies are used when

trying to influence a target person and control for

different ICT. Furthermore, the effect on the target

will be especially dependent on how politically

skilled and media-savvy the agent is.

In addition to aspects related to the variety of

ICT in carrying influence processes one must take

into consideration the social nature of networks

which might have contributed to considerable

variations in the ratings. To broaden the picture,

future research in this field should address relational

aspects such as the quality of the relationship

between agent and target, their respective network

positions and the degree to which political behavior

is addressed openly. Further, individual-level aspects

such as the political skills of the agent and several

other personal competencies might substantially

contribute to a deeper understanding of the inner

dynamics of virtual networks.

The present study offers some methodical

limitations. Since at least 90 parameters were to be

estimated for model calculations, the sample size of

243 data sets was relatively small (Kline, 2005).

Even if samples of n = 200 have been set as a

benchmark by some authors (e.g., Marsh et al.,

1988) a sample of at least n = 250 rather meets the

recommendations of most authors. Another

limitation is set by the selection of the sample.

Despite the fact that targets and non-targets were

randomly selected, they had been listed by the agent

before, and thus belong to a specific pool of network

members. Consequently, effects of sympathy or

other inter-individual preferences may have led to a

selective set of triads. This leads directly to another

important limitation. In fact only cliques within the

network have been evaluated but not the whole

network. However, research on virtual organizations

would require a consideration of the multiple mutual

relations that actually build the network. Thus,

analyses of triads provide only a first step to gain

insights into social influence processes.

Beside these limitations, the study offers

important insights into the social nature of virtual

collaborations: Obviously, peers are aware of the

agent’s influence attempts in virtual networks. So

does being caught in the act blow the agent's cover?

With a view to career advancement some authors

have pointed out that micro-political influence

attempts cannot be carried out as an overt act in

order to be effective (Elron and Vigoda-Gadot,

2006). On this note, it could be argued that covert

influence attempts that are not perceived as such

may even be more powerful, because the target

cannot put up resistance. In our study we

concentrated solely on the observed influence

attempts and refrained from evaluating the success

of influence attempts. Accordingly, questions

concerning the relationship between the obviousness

of tactics and realized effects towards influence

targets cannot be answered. However, at least from a

theoretical point of view, one might assume that in

virtual organizations dealing with influence is

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

558

different. Given the lack of formalized leadership

hierarchies in most virtual organizations, leadership

at its most basic level is the ability to influence

others. Influence tactics can thus be viewed as a

vital–if not necessary–tool for members to get their

way in network issues (Greer and Jehn, 2009). This

dilemma–working at eye level without the formal

authority to give directives but getting work done

together at the same time–requires any form of

informal influence behavior. In the absence of

leadership alternatives, mutual influence is thus

beside joint decisions and collective processes not

only tolerated but often the only leadership

instrument available.

REFERENCES

Abele, S. (2011). Social interaction in cyberspace, Social

construction with few constraints. In Z. Birchmeier, B.

Dietz-Uhler & G. Stasser (Eds.), Strategic Uses of

Social Technology. An Interactive Perspective of

Social Psychology (pp. 84-107). New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Barbuto, J. E. & Moss, J. A. (2006). Dispositional Effects

in Intra-Organizational Influence Tactics: A Meta-

Analytic Review. Journal of Leadership &

Organizational Studies, 12(3), 30-48.

Barry, B. & Fulmer, I. S. (2004). The medium and the

message: The adaptive use of communication media in

dyadic influence. Academy of Management Review,

29, 272-292.

Blickle, G. (2003). Convergence of agents' and targets'

reports on intraorganizational influence attempts.

European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1),

40-53.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural Equation Modeling With

Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and

Programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Campbell, D. T. & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and

discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod

matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81-105.

Driskell, J. E., Radtke, P. H. & Salas, E. (2003). Virtual

teams: Effects of technological mediation on team

performance. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and

Practice, 7, 297–323.

Elron, E. & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2006). Influence and

political processes in cyberspace: The case of global

virtual teams. International Journal of Cross-Cultural

Management, 6(3), 295-317.

Ferris, G., Hochwarter, W., Douglas, C., Blass, F.,

Kolodinsky, R. & Treadway, D. (2002). Research in

Personnel and Human Resources Management (pp.

65-127). Stanford: Elsevier.

Greer, L. L. & Jehn, K. A. (2009). Follow me: Strategies

used by emergent leaders in virtual organizations.

International Journal of Leadership Studies, 5, 102-

120.

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit

indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional

criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation

Modeling, 6, 1-55.

Janneck, M., Staar, H. (2011). Playing Virtual Power

Games: Micro-political Processes in Inter-

organizational Networks. International Journal of

Social and Organizational Dynamics in Information

Technology, pp. 46-66.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural

equation modeling. New York: Guilford.

Latané, B., Liu, J. H., Nowak, A., Bonevento, M. &

Zheng, L. (1996). Distance Matters: Physical Space

and Social Impact. Personality & Social Psychology

Bulletin, 21, 795-805.

Marsh, H. W., Ballah, J. R. & MacDonald, R. (1988).

Goodness-of-fit indices in confirmatory factor

analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological

Bulletin, 88, 245-258.

Okdie, B. M. & Guadagno, R. E. (2008). Social Influence

and Computer Mediated Communication. In K. St.

Amant & S. Kelsey (Eds.), Handbook of Research on

Computer Mediated Communication (pp. 477-491).

Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Okdie, B. M., Guadagno, R. E., Bernieri, F. J., Geers, A. J.

& Mclarney-Vesotski, A. R. (2011). Getting to know

you: Face-to-face vs. online interactions. Computers in

Human Behavior, 27, 153-159.

Pitt, J., Kamara, L., Sergot, M. & Artikis, A. (2005).

Formalization of a voting protocol for virtual

organizations. In Proceedings of the Fourth

international Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents

and Multiagent Systems (pp. 373-380). New York:

ACM.

Sussman, L., Adams, A., Kuzmits, F. & Raho, L., (2002).

Organizatonial politics: tactics, channels, and

hierarchical roles. Journal of business ethics. 40(4),

313-331.

Tidwell, L. C. & Walther, J. B. (2002). Computer-

mediated communication effects on disclosure,

impressions, and interpersonal evaluations. Human

Communication Research, 3, 317-348.

Travica, B. (2005). Virtual organization and electronic

commerce. SIGMIS Database 36(3), 45–68.

Wilson, E. (2003). Perceived effectiveness of

interpersonal persuasion strategies in computer-

mediated communication. Computers in Human

Behavior, 19(5), 537-552.

Yukl, G. & Falbe, C. M. (1990). Influence tactics and

objectives in upward, downward and lateral influence

attempts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(2), 132-

140.

Self-otherAgreementonInfluenceAttemptsinVirtualOrganizations-DoAgentsandPeersSeeEyetoEye?

559

APPENDIX

Table A.1.: English Version of the Virtual Politics Inventory.

To achieve my goals within the network…

Rational Persuasion

I try to convince others with my knowledge in that matter.

I use rational arguments to convince my network partners.

I describe in detail the reasons for my concerns.

I spread information to the network partners to clarify my

concerns.

Assertiveness

I clearly express my displeasure towards my network

partners.

I engage in open confrontation with my network partners.

I put pressure on my network partners.

Inspirational Appeals

I try to highlight that we are all in the same boat.

I call upon our common vision, the basic idea of a network.

I emphasize the need to pull together for being successful.

Self-Promotion

I emphasize my efforts regarding the network collaboration.

I emphasize my value for the network.

I refer to positive outcomes due to my work and/or the

central position of my company within the network.

Exchange

I affirm that I would show my gratitude for a partner’s

favor.

I offer to do my network partner a favor in return.

I promise to reciprocate for my network partner’s support.

Mediating

I achieve my goals better when I behave neutrally towards my partners.

I try to stay neutral and mediate between partners during negotiations

and discussions.

I keep a non-committed position in discussions and controversies

instead of taking sides with a party straight away.

I try to be the mediating tie in cases of disagreement.

Claiming Vacancies

I look for opportunities to play an additional part in the network beyond

my primary role.

I adopt some additional tasks as they turned out to be advantageous.

I take over new tasks and/or roles within the network to extend my

scope of action.

Being Visible

I always try to show presence via electronic media.

I purposefully use electronic media to call attention to my concerns.

I always try to be available and present on all communication channels.

Inspiring Trust

I try to appear open-minded about my network partners’ concerns from

the very beginning.

I purposefully try to show that I am a good and worthy network partner

(showing mutual exchange, trustworthiness, etc.).

I purposefully present myself as a network partner who is willing to

share information and resources.

Right from the start I tried to show my reliability towards the other

network members.

Table A.2.: Multitactic-Multisource-Matrix: Scale Means, Standard Deviations and Convergent Validity Coefficients (n =

729; 243 triads).

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

560