The Influence of Stressors on Usability Tests

An Experimental Study

Monique Janneck

1

and Makbule Dogan

2

1

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science,

Luebeck University of Applied Sciences, Luebeck, Germany

2

eparo GmbH, Hamburg, Germany

Keywords: Usability Testing, Laboratory Tests, Stressors, Validity.

Abstract: In this study we investigated whether the experience of stressors would influence the performance of users

in usability tests as well as their subjective rating of the usability of an interactive system. To that end, an

experimental study was conducted comparing a usability test that was performed in the lab under quiet,

relaxed conditions with a test situation where several stressors (time pressure, noise, social pressure) were

applied. Results show that participants in the stress condition did considerably worse regarding the

completion and correctness of the tasks. The stress and negative feelings the participants experienced also

influenced their view of the tested software. Participants in the stress condition rated the usability of the

software and their user experience considerably more negative. Implications for the practice of usability

testing are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Usability tests are an important method to determine

the usefulness of interactive systems and products in

realistic settings and with real users: In usability

tests, participants solve tasks that they would

typically work on with a certain system. By

observing the interaction, problems and difficulties

can be determined and corrected in the software.

Furthermore user acceptance and satisfaction can be

measured.

Usability tests are often conducted in usability

labs, which are equipped with specialized hardware

and software for audio and video recording, mouse

tracking, screen recording or eye-tracking analysis.

Usability tests usually cover ‘normal’ use cases

and conditions: It is observed what works well and

what problems arise in a regular use situation.

Supported by the analysis techniques named above,

experimenters are able to gain manifold insights into

user behavior and possible improvements of the

software.

However, in the laboratory important context

factors might not be as present as in the real

situation or even suppressed altogether (cf.

Greifenender, 2011), such as noise, presence of

other people, interruptions, bad or bright lighting,

special hardware etc.

Imagine, for example, an electronic train ticket

vending machine. People typically use such systems

in a public situation, possibly in a hurry because the

train is leaving shortly, pressured by others waiting

in the queue. It is easy to imagine that testing a

vending machine under such conditions will yield

other results that in a quiet and relaxed usability lab.

In many areas simulations are used to

specifically test how users and systems perform

under difficult conditions or in risky situations, e.g.

when training pilots or staff of safety-critical

facilities and equipment.

In this paper we investigate the use of stressors

in regular usability tests (i.e., not especially

regarding safety-critical systems) to find out how

they possibly influence users’ performance and also

their evaluation of the product or system they tested.

To that end, we conducted an experiment to compare

usability tests under regular laboratory conditions

with a situation where several stressors were

induced, such as time pressure, noise, and social

pressure.

581

Janneck M. and Dogan M..

The Influence of Stressors on Usability Tests - An Experimental Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0004501405810590

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (STDIS-2013), pages 581-590

ISBN: 978-989-8565-54-9

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Usability Testing

According to ISO 9241-11 (ISO, 1998) usability is

defined as the extent to which a product can be used

by specified users to achieve specified goals in a

specified context of use (users, tasks, equipment and

environment). It can be established by measuring the

effectiveness of use (if a certain task can be

completed), efficiency of use (i.e. the time and effort

necessary to complete the task) and also the

satisfaction with use as reported by the users.

Furthermore for several years the concept of user

experience (UX) has been discussed as an expansion

of the traditional usability definition. User

experience relates to the emotional experience of

using an interactive product: Positive and negative

feelings, attitudes, beliefs, biases and preferences of

users. Therefore usability is only one factor

influencing user experience (cf. Tullis & Albert,

2008).

Usability is measured with a variety of different

methods, such as heuristic evaluation, walkthrough

or inspection methods, and usability questionnaires

(e.g. Shneiderman & Plaisant, 2010). Especially for

measuring user experience, a number of specialized

questionnaires have been developed, such as

AttrakDiff (Hassenzahl, 2008) or UEQ (Laugwitz et

al., 2008).

Usability tests in the lab, however, are still seen

as the ‘silver bullet’ of usability evaluation, as stated

by Jakob Nielsen as early as 1993: “User testing

with real users is the most fundamental usability

method and is in some sense irreplaceable“ (Nielsen,

1993, p. 165). The popularity of the method is due to

the exactness and scope of results, even if it’s often

more costly and time-consuming than other

evaluation methods. The sophisticated recording and

analysis methods and tools that are available, as

mentioned in the introduction, contribute to the

quality of the results.

Nevertheless, mobile or remote usability tests are

increasingly popular (cf. Bosenick et al., 2007).

Mobile usability tests take the laboratory to the field

by testing systems in a real use context, e.g. using a

mobile lab on a notebook. Remote tests offer even

more flexibility: The test persons carry out the test

via Internet at their own computers with the

experimenter not being present (however, a test

supervisor might be available online).

While mobile or remote usability tests might be

able to capture the actual conditions of use better

than a lab test (at the expense that some recording

and analysis methods are not available), they still do

not explicitly incorporate simulations or stressors.

On the opposite: Most guidelines for conducting

usability tests recommend establishing a quiet,

relaxed atmosphere for users to work in without

feeling anxious or pressured. Instructions for test

users often emphasize that the system is being tested

and not the user – therefore the user is not to blame

for anything that might go wrong (e.g. Dumas &

Loring, 2008, Dumas & Redish,1999).

However, in everyday use, errors and stress are

frequent occurrences when dealing with computer

systems (e.g. Ayyagari et al., 2011).

2.2 Stress and Errors

Stress is defined as an individuals’ reaction to events

that threaten to cause an imbalance by overstraining

his or her resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007,

Janssen et al., 2001). In the short run, physical

reactions to stressors support an individual to face

the stressful situation by mobilizing bodily

resources. However, in the long run stress can have

serious negative consequences for physical and

psychic health, such as high blood pressure, heart

diseases, sleeping disorders, fatigue, anxiety or

depression (Ogden, 2007).

There are many different types of stressors.

Stressors include major life crises, such as a divorce

or loss of job, as well as small nuisances, so-called

‘daily hassles’, such as paper jams, minor conflicts

and quarrels, a delayed bus and so forth, that

nevertheless might build up to a substantial

experience of stress (Kanner et al., 1981). Especially

at work, factors that hinder people to successfully

complete their tasks are known to induce stress.

Among them are time pressure, lack of necessary

resources, over- or non-taxing demands or social

stressors, such as a lack of support by others (Frese

and Zapf, 1994, Semmer, 1984, Sonnentag and

Frese, 2003).

It is important to note that different people might

experience the same stressors very differently,

depending on the resources they have available

(Bakker and Demerouti, 2007, Frese and Zapf,

1994) or factors of resilience (Robertson, 2012).

As is known from work psychology stress has an

impact on performance (e.g. Driskell and Salas,

1996). Stress especially increases error and leads to

a lack of concentration. Regarding the use of

computer systems this might result in simple

sensomotor errors like typos or wrong clicks as well

as careless mistakes, misconceptions or a lack of

control (cf. Reason, 1990).

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

582

Quite surprisingly, stress in usability testing has

seldom been researched so far. One of the few

existing studies conducted by Andrzejczak and Liu

(2010) compared the effect of the test location (lab

vs. remote) on user anxiety, finding no meaningful

differences. Some authors explored the use of

biological and psycho-physiological measures in

usability testing to detect arousal (Stickel et al.,

2008, Lin et al., 2005). However, to our knowledge,

the experimental use of stressors has not been

investigated systematically so far.

Given the relevance of stressors in daily life on

the one hand and the lack of research regarding

stressors in usability tests on the other hand the

following research questions are framed:

- Can stress be successfully induced in a

laboratory setting of usability tests?

- Does stress substantially influence users’

performance in usability tests?

- Does the experience of stress affect users’

evaluation of the interactive products they are

testing?

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Sample and Procedure

To test the influence of stressors on the test person’s

performance in a usability test and their subjective

evaluation we conducted an experiment with a total

of N=20 participants (50% male, 50% female; age

20-35 years). Participants were told that they were

supposed to test the search and checkout procedure

of a large online shop (Amazon). We selected test

persons who were frequent Internet users and also

experienced online shoppers to be able to separate

the effects of stressors from general usage problems.

All test persons had shopped at Amazon before.

The test persons were assigned at random to one

of the following conditions:

- Regular usability test (N=10, 5 male, 5 female):

The participants took part in a usability test in a

quiet, undisturbed environment. They received a

list of items they were supposed to search at

Amazon and add to the shopping cart. After they

had completed the search task they were given the

required log-in data and were asked to complete

the checkout procedure. Before finalizing the

purchase, they were asked to remove some of the

items from their shopping cart and add some other

products.

- Usability test with stressors (N=10, 5 male, 5

female): The participants were asked to complete

the same tasks as in the first condition. However,

during the usability test several stressors were

applied:

Time Pressure. Participants were told that there

was a 5-minute time limit for the search as well

as the checkout task. A stopwatch was put up

visibly on the table.

Noise and Disturbance. During the test a person

enters the test room and angrily asks for a

cable. The test supervisor hectically searches

for the cable in a locker, making noise and

dropping several items. Then the test

supervisor leaves to fetch the cable from

another room.

Social Pressure. After the test supervisor left

the room, the unknown person takes a seat

directly next to the test persons, observing

them while they are working on their tasks and

constantly drumming with his fingers on the

table.

Upon return, the test supervisor apologizes for the

disturbances and politely asks the test persons to

complete the tasks, reminding them of the time

limit.

3.2 Measures

In both conditions the tests were conducted in a

usability lab equipped with audio and video

recording as well as eye tracking. Morae© software

was used for audio, video, mouse and screen

recording. Nyan© was used for eye tracking

analysis.

For performance measures, task completion and

correctness were recorded. Furthermore the time

that participants needed to complete the tasks was

measured.

For measuring the perceived usability of the

product all test persons rated Amazon using the

AttrakDiff questionnaire (Hassenzahl, 2008) after

completing the usability tests to measure whether the

stress experience had an influence on user ratings.

AttrakDiff measures usability of interactive products

as well as user experience and joy of use by means

of a semantic differential, i.e. pairs of words (the

word pairs can be seen in figure 5). The

questionnaire addresses four dimensions:

- Pragmatic Quality, measuring the usability of the

interactive product,

- Hedonic Quality, which refers to the user

experience and is split up in two subscales of

‘Identity’ (measuring identification) and

‘Stimulation’ (measuring innovativeness and

originality of the product).

TheInfluenceofStressorsonUsabilityTests-AnExperimentalStudy

583

- Attractiveness, referring to the overall

attractiveness of the product.

Validity and reliability of the instrument were

established in several studies (Hassenzahl, 2008).

AttrakDiff was chosen since it is especially suitable

to measure subjective and also emotional aspects of

use.

Furthermore the participants filled out a

questionnaire containing several items related to the

test situation and the stress they possibly

experienced (see table 2) measured on a 5-point

Likert scale (ranging from 1=’not at all’ to 5=’very

much’).

Table 1: Items measuring participants’ experience of the

test atmosphere and possible stress.

Please indicate how much you agree to the following

statements:

• I did not care about the test.

• I felt distracted.

• I had difficulties concentrating.

• I felt pressured.

• I was stressed by the situation.

• I was anxious to fail.

• I wanted to leave the situation.

• I was annoyed.

• I would have liked to get support.

After completing the questionnaires the test

persons who had participated in the stress condition

were also interviewed by the test supervisor to gain a

deeper understanding of their experiences and their

emotions during the test situation. At the beginning

of the interview the real purpose of the study and the

deliberate nature of the disturbances was revealed to

the participants.

4 RESULTS

The general observations made by the test

supervisors revealed remarkable differences between

the two test conditions. In the regular condition

participants worked on the tasks in a relaxed manner

and had no serious problems completing the tasks.

In the stress condition, test persons showed a

considerable amount of frustration as a reaction to

the stressors applied in the situation. Most test

persons appeared nervous, distracted, and sometimes

aggressive. Many of them had remarkable

difficulties when working on the tasks.

These general observations were confirmed by

the performance and usability measures as well as

the measures related to the stress experiences.

Results are reported in the following sections.

4.1 Performance Measures

4.1.1 Task Completion and Correctness

Test persons in the regular and the stress condition

showed remarkable differences regarding their

performance.

In the regular condition, all test persons were

able to complete both the search and the checkout

task. Error rates were low (as reported further on).

In the stress condition, all test persons made a

substantial amount of errors in the search phase.

Only two persons were able to complete the

checkout procedure.

Table 2 shows the percentage of items that were

correctly identified and added to the shopping cart.

In the regular condition, almost all purchases were

correct. In the stress condition, test persons chose

the wrong items in more than half of all cases.

Observations by the test supervisor during the

tests add to the impression that participants in the

stress condition were generally much more error-

prone (e.g. regarding typos and careless mistakes)

and at the same time less likely to recognize their

mistakes, while participants in the regular condition

often noticed their errors and were able to make

corrections themselves right away.

Table 2: Correctness measures.

Regular

condition

Stress

condition

Correct products in

shopping cart

91% 48%

Incorrect products

in shopping cart

9% 52%

Overall number of

errors in checkout

phase

8 [merely typos] 15 [mainly

problems in

comprehension]

Persons completing

all tasks

10 (out of 10) 2 (out of 10)

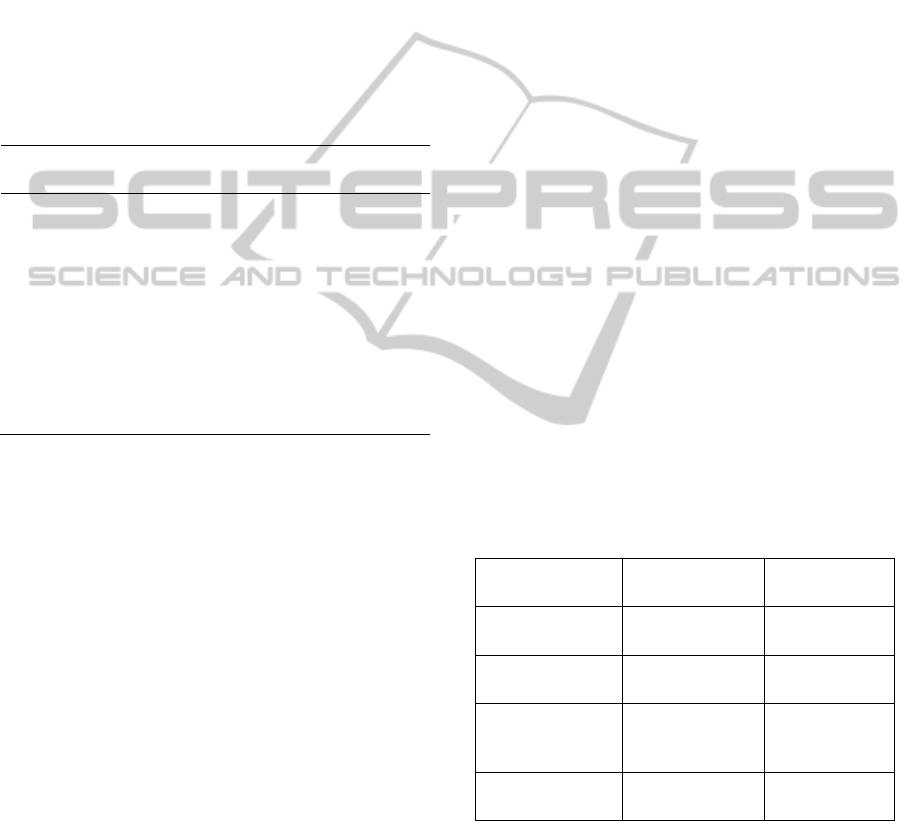

Furthermore, eye-tracking analyses reveal much

more ‘scattered’ and unorganized track paths among

participants in the stress conditions (figure 1).

Also, participants in the stress condition tended

to focus on parts of the screen that were irrelevant

for the current task (see figures 2 and 3).

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

584

Figure 1: Scattered scan path of participant in the stress

condition.

Figure 2: Relevant focus (on fields of address form) in

scan path of participant in the regular condition.

Figure 3: Irrelevant focus in scan path of participant in the

stress condition: The error message and the corresponding

text fields are not recognized by the person.

4.1.2 Time Measures

Since time restrictions were placed on the

participants in the stress condition while in the

regular condition test persons were free to work on

the tasks as long as they wished, it was not

reasonable to compare task completion times

directly.

Instead, regarding the search task we compared

the number of items that participants identified and

placed in their shopping carts in five minutes (the

time limit imposed in the stress condition).

Regarding the checkout task – as most participants

in the stress condition failed to complete this task

altogether – we compared the time the test persons

needed to fill out the address form, as this was a

relatively simple task.

Results (table 3) show that in the regular

condition test persons were faster and identified

more items (and more often the correct items, as was

pointed out in section 4.2.1). Even though the

differences were small, this is quite remarkable since

the participants in the regular condition could be

expected to work in no hurry.

Interestingly, standard deviation was much

higher in the stress condition than in the regular

condition. This reflects that obviously some test

persons were affected more by the stressors than

others.

Table 3: Time measures.

Regular

condition

Stress

condition

Average number of products in

shopping cart after 5 minutes

6.9 5.6

Average time for address

completion (in seconds)

61.5

(SD=7.4)

65.6

(SD=19.0)

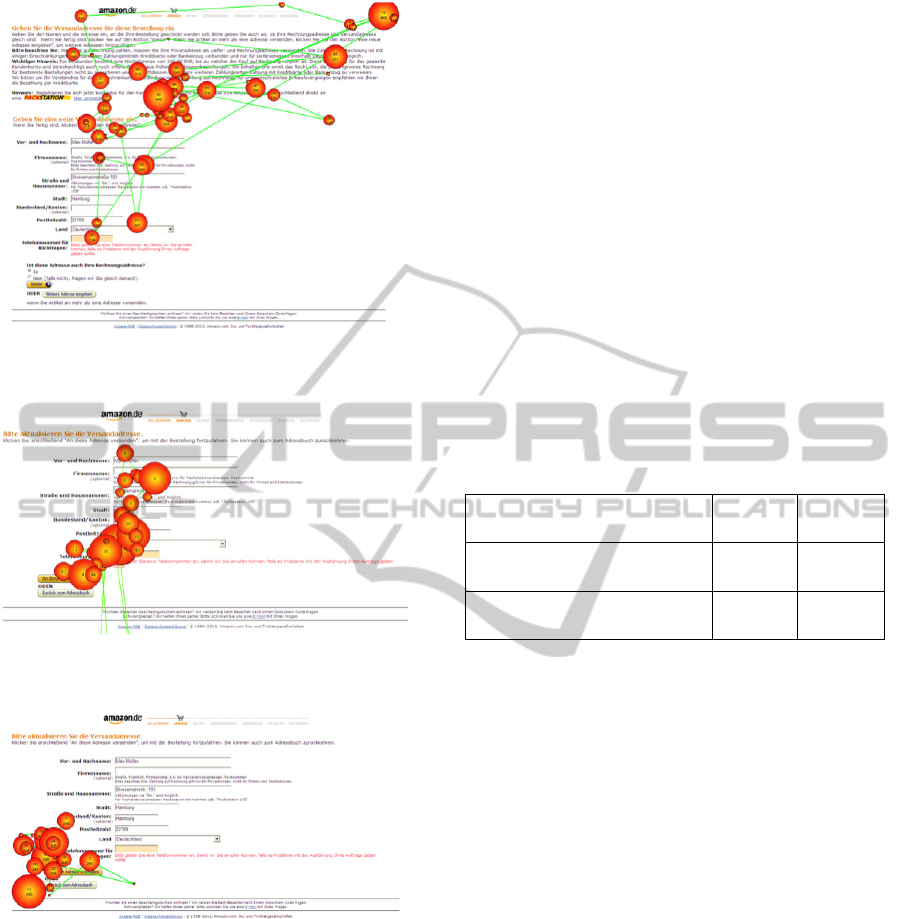

4.2 Usability Measures

In the following section the AttrakDiff ratings of the

participants in the regular vs. the stress condition are

compared as a measure of perceived usability.

Again, remarkable differences can be found. In

the regular condition, the ‘pragmatic quality’ (PQ),

i.e. the usability of the Amazon online shop, was

rated very positively. ‘Hedonic quality’, i.e. the user

experience, was rated above average. In the stress

condition, ratings were much lower: Values for both

usability (PQ) and HQ (user experience) were below

average.

Figure 4 shows the mean values of the four

AttrakDiff dimensions (PQ=Pragmatic Quality; HQ-

I=Hedonic Quality/Identity; HQ-S=Hedonic Quality

/Stimulation; ATT=Attractiveness). Regarding all of

the four dimensions the Amazon website was rated

more negatively (with values below average) by

participants in the stress condition. Differences were

especially large regarding Pragmatic Quality and

general Attractiveness. These differences were

statistically significant (p<0.05).

Furthermore, the confidence interval for the

stress condition is much larger, indicating a wide

TheInfluenceofStressorsonUsabilityTests-AnExperimentalStudy

585

Figure 4: Mean values for regular condition (upper curve)

and stress condition (lower curve) regarding the four

dimensions of AttrakDiff.

range of ratings among the participants. Again, this

shows that the test persons were affected differently

by the stressors.

Figure 5 shows the differences between the

regular and the stress condition regarding all items

of the questionnaire.

Figure 5: AttrakDiff profile for regular condition (right

curve) and stress condition (left curve).

4.3 Experience of Stress

In the following sections the results of the

questionnaire measuring the participants’ perception

of the test situation and the interviews with those

participating in the stress condition are depicted.

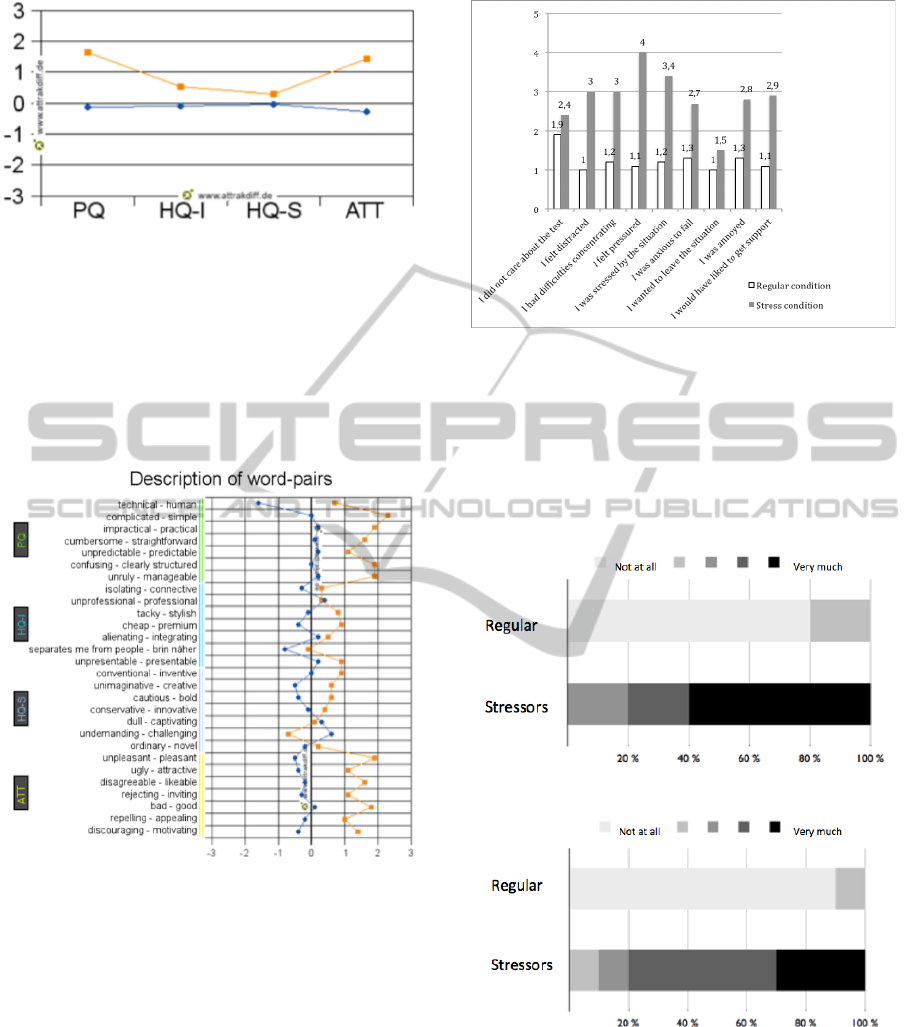

4.3.1 Questionnaire

Figure 6 shows the mean ratings for both conditions.

For all items except for ‘I did not care about the test’

and ‘I wanted to leave the situation’ participants in

the stress conditions gave significantly more

negative ratings (p<0.05).

Figure 6: Mean values for items measuring stress during

the test.

Especially large differences can be found regarding

the experience of pressure, feelings of stress,

distraction and difficulties concentrating. Also,

participants in the stress condition longed for more

support. Figures 7 and 8 give some especially

impressive examples.

Figure 7: Respondents experiencing stress.

Figure 8: Respondents experiencing pressure.

4.3.2 Interviews

The interviews that were conducted with the

participants in the stress condition clearly reflect the

results of the performance measures as well as the

stress questionnaire.

All respondents said that they had experienced

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

586

some form of negative emotions during the test,

some of them very gravely:

“I was almost freaking out. I was nervous and

had difficulties concentrating. That was totally

absurd.” (Person 3, female)

Several persons reflected on the experience that

they failed to complete seemingly easy tasks:

“Everything was so difficult. Usually I would

handle that.” (Person 2, female)

Regarding the different stressors, the interviews

indicate that time pressure and social pressure were

experienced as especially stressful:

“Without the time pressure I would have looked

more closely at the products.” (Person 5, male)

“That man. He was really annoying, simply

because he sat next to me. I thought he was

surely looking over my shoulder and thinking,

‘Oh, she can’t do it’. That was really

disturbing.” (Person 2, female)

“I had even more difficulties concentrating after

your colleague came in. I was on the verge of

saying, ‘please go out, can’t you wait somewhere

else?’” (Person 6, female)

The interviews also show interindividual

differences regarding the perception of stressors.

Especially noise and distraction were handled

differently according to prior experiences:

“I know that kind of situation from my home. I

have two smaller siblings. I can switch that off.”

(Person 7, male)

“I worked as an online journalist for three years,

therefore I can handle noise. It was always noisy

there, everybody was shouting, the telephone was

ringing, visitors around…” (Person 8, female)

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Interpretation of Results and

Methodical Issues

In this study we investigated if stress could be

induced in a usability test and whether the

experience of stressors would influence the

performance of users as well as their subjective

rating of the usability of an interactive system. To

that end, an experimental study was conducted

comparing a usability test that was performed in the

lab under quiet, relaxed conditions with a test

situation where several stressors (time pressure,

noise, social pressure) were applied.

All three research questions can be answered

with ‘yes’:

Regarding their performance, participants in the

stress condition did considerably worse regarding

the completion of the online shopping tasks. More

than half of the items that were added to the

shopping cart were incorrect, compared to only 9%

in the regular condition. They made numerous

mistakes and were mostly unable to recognize and

correct them. Furthermore, stressed participants

were less efficient: They needed slightly more time

and identified less products even though they had

been given a time limit and therefore were trying to

work fast.

This is especially remarkable since all

participants were experienced and frequent Internet

users. All of them were familiar with online

shopping in general and had also particularly used

Amazon before. That means in prior situations they

had successfully performed the very tasks that they

were failing during the test.

The stress and negative feelings that the

participants experienced also influenced their view

of the software they tested. Participants in the stress

condition rated the usability of the software and their

user experience considerably more negative:

Obviously, negative emotions of test users are

projected on products they use. To put it the other

way around: To a certain degree positive usability

ratings might reflect not only the actual product

quality, but also the positive well-being of the users.

Given the research from work psychology

regarding the influence of stressors on work

performance, it is not surprising as such that stress

also influences computer-related tasks. Nevertheless,

the magnitude is remarkable: The test persons failed

to complete simple tasks that they had done

numerous times before and that were solved easily

by the participants in the regular condition. During

the checkout procedure the total number of errors

almost doubled. What is more, while test persons in

the regular condition merely produced typos, which

they were able to correct themselves right away,

participants in the stress condition showed a general

lack of understanding or chose wrong strategies that

caused them to fail the task altogether (only two out

of 10 persons in the stress condition were able to

complete the checkout procedure).

The variance regarding performance measures as

well as usability ratings was much higher in the

stress condition. This reflects the finding that people

TheInfluenceofStressorsonUsabilityTests-AnExperimentalStudy

587

experience stress quite differently (Bakker and

Demerouti, 2007, Frese and Zapf, 1994, Robertson,

2012). In the interviews conducted with the

participants in the stress condition some test persons

also emphasized that they had not been disturbed as

much because they were used to working in noisy

and turbulent environments.

Quite interestingly, especially the female test

persons felt extremely bothered by the (male) person

disturbing and observing them. Whether gender is an

issue here needs to be clarified in further studies.

However, the present study has several

shortcomings. First of all, the number of participants

was relatively low. While testing 20 persons can be

expected to yield good results in a ‘real’ usability

test (Faulkner, 2003), the results cannot be

considered representative in a scientific study. Also,

we purposefully included especially younger people

who were experienced Internet users to make sure

the participants would be principally able to

complete the tasks with ease. It is quite impressive

that even experienced users were affected by the

stressors to such a large extent. However, further

research is needed to show whether the effects

identified in this study also hold for other groups of

computer users.

Due to the small number of participants we were

also unable to conduct more differentiated analyses.

For example, it would be interesting to investigate

whether the amount of stress that is experienced by a

person is correlated with performance and usability

measures. Also, the gender differences that were

suggested by the interview results could not be

analyzed in detail because the number of participants

in the stress condition was too low.

Furthermore, we did not separate the distinct

effects of the different stressors used in this study. In

the interviews the test persons indicated that

especially time pressure and social pressure (i.e. the

presence of an unknown and unfriendly observer)

were experienced as stressful and annoying.

Whether certain types of stressors have specific

effects on performance and product evaluation needs

to be clarified in future research.

5.2 Implications

The results of our study have several serious

implications for usability research as well as the

practice of usability testing.

First of all, it has to be stated that stress can

easily be invoked during usability tests. Often, this

might be unintentional and go unnoticed by the

experimenters.

Especially when using remote usability tests or

questionnaires to assess usability or user experience

of an interactive product, it seems hard to assess

whether stress that the users were possibly

experiencing might have influenced the results.

Furthermore, measures and methods that are

regularly used in usability testing might induce

stress – at least in some test persons – without the

intention to do so.

Imposing a time limit, for example, proved to be

a simple and effective stressor making test persons

anxious and nervous and also causing them to work

less effectively and efficiently compared to the no-

stressors condition. As time measures are a regular

method in usability studies and time limits are

frequently announced for simple administrative

reasons this might be an important source of error

when interpreting the results.

Likewise, social stressors (i.e. the presence of an

unknown person observing the participants) had a

strong effect on the test persons. Again, supervisors

and observers participating in usability tests might

have an irritating effect on the test persons and their

performance, especially if the presence of observers

is not adequately explained and justified.

While stress can be seen as a confounding factor

in usability studies, including stressors might also

have a beneficial effect. As was already stated in the

introduction, some interactive products are typically

used in stressful situations (e.g. buying a train ticket

at an electronic vending machine while other people

are watching and waiting and the train is about to

arrive). Assessing the usability of such products in a

relaxed atmosphere is likely to produce false results.

Likewise, safety-critical systems need to function

well in emergency situations. Therefore it should be

tested how users perform under stress.

Apart from such special scenarios, our results

suggest that stressors should be regularly included in

usability testing as a control variable to get a broader

and more complete picture of how users interact

with a system. This is especially important when

conducting usability tests in the lab, where users

typically experience a quiet and relaxed atmosphere

(cf. Bosenick et al. 2007, Dumas and Loring, 2008,

Dumas and Redish, 1999).

Of course, stressors in usability tests should not

be used arbitrarily, but rather need to be related to

the expected use scenarios. Time constraints, for

example, might be especially relevant for all

interactive systems used in a work context, since

people are usually expected to work fast and

efficiently. On the other hand, it might seem odd to

impose a time limit when testing a product or system

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

588

that is primarily intended for private, leisure-time

use when people can be expected to be somewhat

relaxed. Social pressure, of course, is relevant for all

kinds of systems used in public, including public

information systems, vending and teller machines,

and also mobile devices. Also, people working in

open-plan offices or generally with other colleagues

or customers around might experience social

pressure that should be considered when planning

usability tests. Likewise, the occurrence of noise,

interruptions and other kinds of disturbances can be

derived from use-cases and scenarios.

Furthermore, interindividual differences

regarding the level of stress should be considered

when trying to assess the effect of stressors on

usability tests. While some people might be hardly

affected, others experience profound stress and

anxiety. Simple and short questionnaires like the one

we used in our study can help to judge the impact

that such feelings had on test results.

One might argue that our results indicate that we

should leave the lab altogether and conduct usability

evaluations in the field instead to achieve really

meaningful results. Indeed, on-site investigations

and observations of actual work processes and user

experiences are particularly valuable, especially

regarding usability engineering and socio-technical

design: When developing or implementing a new

system in an organization it is crucial to involve real

users in their real environments. Nevertheless, the

lab might be preferred in several situations; e.g. in

early stages of product design when actual users are

not yet available, for test cases where sophisticated

observation and recording technologies are

desirable, to simulate certain occurrences, or simply

because on-site testing is not possible for

administrative or other reasons. In these cases

inducing stressors in lab tests can enhance results.

However, the question of external validity should

always be asked when working in the lab.

Of course the deliberate use of stressors raises

ethical issues and considerations. We were surprised

about the strong effects the stressors used in our

study had on the participants. Many of them

experienced a substantial amount of stress, anger

and frustration. How to handle these feelings, e.g. by

clarifying the goals and intentions of the study in a

follow-up interview as we did in our study, needs to

be carefully planned in advance.

REFERENCES

Andrzejczak, C., Liu, D. (2010). The effect of testing

location on usability testing performance, participant

stress levels, and subjective testing experience.

Journal of System Software 83, (7), 1258-1266.

Ayyagari, R., Grover, V., Purvis, R. (2011). Technostress:

technological antecedents and implications. MIS

Quarterly 35, (4), 831-858.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-

resources model: State of the art. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 22 (3), 309-328.

Bosenick, T., Kehr, S., Kühn, M., Nufer, S. (2007).

Remote usability tests: an extension of the usability

toolbox for online-shops. In Proceedings of

UAHCI'07, Berlin: Springer, 392-398.

Driskell, J., Salas, E. (Eds) (1996). Stress and human

performance. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Dumas, J.S., Loring, B.A. (2008). Moderating Usability

Tests: Principles and Practices for Interacting. San

Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

Dumas, J.S., Redish, J.C. (1999). A practical guide to

usability testing (revised). Willmington: Intellect.

Faulkner, L. (2003). Beyond the five-user assumption:

Benefits of increased sample sizes in usability testing.

Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and

Computers, 35 (3), 379-383.

Frese, M., Zapf, D. (1994). Action as the core of work

psychology: A German approach. In H. C. Triandis,

M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of

industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 271-

340). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.

Greifeneder, E. (2011). The impact of distraction in

natural environments on user experience research. In

Proceedings of TPDL'11, Berlin: Springer, 308-315.

Hassenzahl, M. (2008). The interplay of beauty, goodness,

and usability in interactive products. Human-

Computer Interaction 19, (4), 319-349.

International Standards Organization (1998): Ergonomic

requirements for office work with visual display

terminals, part 11 (ISO 9241-11).

Janssen, P. P. M., Bakker, A. B., De Jong, A. (2001). A

test of the demand-control-support model in

construction industry. International Journal of Stress

Management, 8 (4), 315-332.

Kanner, A.D., Coyne, J.C., Schaefer, C., Lazarus, R.S.

(1981). Comparison of two modes of stress

measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major

life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 1-39.

Laugwitz, B., Held, T., Schrepp, M. (2008). Construction

and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In

Proceedings of USAB 2008, Berlin: Springer, 63-76.

Lin, T., Omata, M., Hu, W., Imamiya, A. (2005). Do

physiological data relate to traditional usability

indexes?. In Proceedings of OZCHI '05, Narrabundah,

Australia, 1-10.

Ogden, J. (2007). Health Psychology: a textbook (4th ed.).

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Reason, J. (1990). Human Error. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Robertson, D. (2012). Build your Resilience. London:

Hodder.

TheInfluenceofStressorsonUsabilityTests-AnExperimentalStudy

589

Shneiderman, B., Plaisant, C., (2010). Designing the user

interface. Strategies for effective human-computer

interaction. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 5

th

edition.

Sonnentag, S., Frese, M. (2003). Stress in Organizations.

In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.),

Handbook of psychology: Industrial and

Organizational Psychology (Vol. 12, pp. 453-491).

New York: Wiley.

Stickel, C., Scerbakov, A., Kaufmann, T., Ebner, M.

(2008). Usability Metrics of Time and Stress -

Biological Enhanced Performance Test of a University

Wide Learning Management System. In Proceedings

of USAB '08, Berlin: Springer, 173-184.

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

590