Using Knowledge Management Tools and Techniques to Increase the

Rate of Attendance at Breast Screening

Rajeev K. Bali

1

, Jacqueline Binnersley

1

, Vikraman Baskaran

2

and M. Chris Gibbons

3

1

BIOCORE Applied Research Group, Coventry University, Puma Way, Coventry, U.K.

2

College of Continuing and Professional Studies, Mercer University, Atlanta, U.S.A.

3

Johns Hopkins Urban Health Institute, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, U.S.A.

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Breast Screening, Barriers to Attendance.

Abstract: Breast screening is an important method of detecting cancer early, with around a third of breast cancers now

diagnosed through screening. Previous research has demonstrated that there are many contributors to health

inequalities, with poor access to good health services chief among them: there are significant disparities in

the use of health services linked to income, ethnicity and education. Empirical data was analysed from a

breast screening service (n=159,405) using advanced data mining techniques, as well as being collected

from service users by way of two focus groups conducted before and after the use of a detailed

questionnaire (n=102). The results were used to make recommendations of interventions to reduce the rate

of non-attendance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women,

with over 40,000 being diagnosed each year in the

UK (Cancer Research UK, 2005). Screening is an

effective way to detect cancer early, with around a

third of breast cancers being diagnosed in this way.

There is currently a screening program catering to

almost two million women in the UK (Cancer

Research UK, 2005), which screens all eligible

women every three years. The information published

by the UK Government Statistical Service has

shown that for the ten years since 1995, the uptake

has remained constant at around 75%.

Previous research has shown that non-attendance

is associated with having to travel long distances to a

screening centre (Baskaran, 2008), with a woman’s

economic background and a lack of family support

(Katz et al., 2000). According to Bekker et al.

(1999), non-attendance can be attributed to

disinterest, negative attitudes, beliefs, medical

problems and fear of X-rays. These factors could be

addressed by educating people about the importance

of screening and tackling some of the socio-cultural

and personal barriers to attendance (Cassandra,

2006). Baskaran (2008) was able to predict breast

screening attendance using factors such as age,

previous attendance, postal area, past cancer history,

history of a false positive result and a representation

of socio-economic status called the Townsend score

(Townsend et al., 1988).

Semi-permanent factors such as ethnicity, age,

marital status, income, education and long term

conditions may affect whether women attend

screening (Katz et al., 2000). These may be more

difficult to address than temporary factors such as

employment, personal apprehensions, beliefs,

knowledge and access to screening facilities (Sin

and Leger 1999, Bekker et al., 1999). It has been

found that using mobile screening units rather than

expecting women to travel long distances can

improve attendance rates (Day et al., 1989).

Interventions with educational materials have

limited effectiveness but when used in conjunction

with primary care initiatives they can help women to

make informed decisions about screening (Jepson et

al., 2000). Primary care can address some of the

temporary factors, such as personal apprehensions,

beliefs and knowledge (Fox et al., 1991; Bekker et

al., 1999). Bankhead et al. (2001) found letter based

interventions by primary care to be effective and

Atri et al. (1997) found a telephone intervention to

be effective.

Baskaran (2008) used the techniques and tools of

knowledge management to identify women with

344

K. Bali R., Binnersley J., Baskaran V. and Chris Gibbons M..

Using Knowledge Management Tools and Techniques to Increase the Rate of Attendance at Breast Screening.

DOI: 10.5220/0004544503440350

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval and the International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2013), pages 344-350

ISBN: 978-989-8565-75-4

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

characteristics associated with non-attendance at

breast screening. Knowledge management is an

approach that is concerned with the creation and

sharing of knowledge, with the aim of improving the

efficiency and effectiveness of organisations (Bali et

al., 2009). Early detection has a huge impact on

reducing cancer related deaths (Baskaran, 2008) and

therefore, the primary concern is to reduce non-

attendance (Bankhead et al., 2001).

2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

The current project aimed to use the tools and

techniques of knowledge management to identify

women who face barriers to breast screening

attendance and to suggest effective ways of

overcoming these. The objectives were to:

Show that screening non-attendance can be

attributed to demographic factors and

screening history

Understand the reasons why some women

fail to participate in the program

Examine inequalities and disparities in

relation to accessing screening

Recommend interventions to reduce the

impact of the barriers and increase the rate

of attendance at breast screening

3 METHODS

Stage One: (Quantitative) Analysis of

Screening Records

The Warwickshire, Solihull and Coventry Breast

Screening Service is part of the National Breast

Screening Program and invites around 55,000

women to participate each year. Data mining

techniques were used to analyse a large number of

the records of service users.

Stage one of the current study used two distinct

approaches. The first approach focused on predicting

non-attendees and the second approach used results

generated at the end of the screening episodes to

identify those women who had failed to attend.

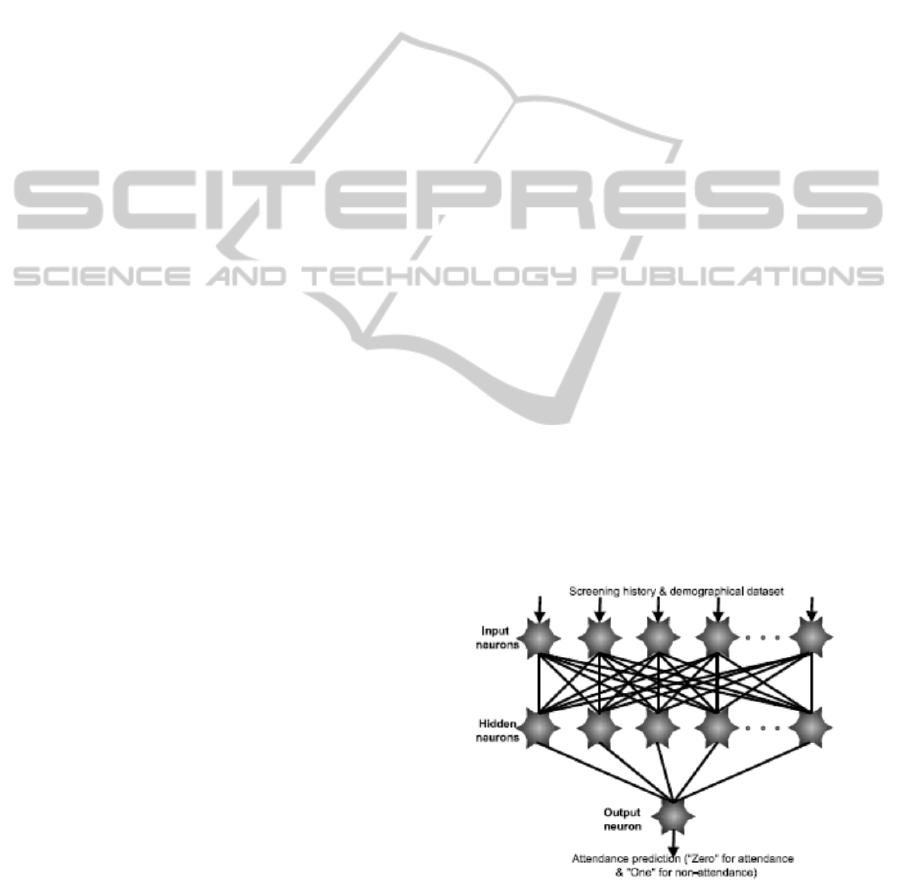

The first approach used an artificial intelligence

algorithm (which embedded knowledge

management activity) to predict non-attendance. It

employed Neural Network algorithms and included

a Service Orientated Architecture to deliver the

knowledge. This work combined the existing

National Breast Screening Computer System

software into a single platform and created a

prototype software component based on Open

Source technologies. The prototype software was

automated to produce the pre-processed data and

eventually normalise the data for artificial

intelligence (neural network) assimilation. These

activities were performed sequentially.

The Java Based Attendance prediction by

Artificial Intelligence for Breast Screening model

was simulated on the Open Source technology

platform. It used historical screening data and

demographic information from the National Breast

Screening database as predicting factors. This was

converted to a flat file and formed the dataset that

was presented to the input neurons. The output

neuron remained at ‘zero’ when a woman was

predicted to attend screening and showed ‘one’ for a

non-attendee (see Figure one). Earlier research had

confirmed that one hidden layer would suffice to

map any multivariate type of input domain to the

output domain. During the training stage, the error

function was fed back through the network from the

output neuron. The knowledge capture was

implemented using the architecture shown in figure

one.

The user (via the GUI interface) pointed the

neural networks to the location of the historical data

(in the flat file) to train the network. Once the

training was completed, the net was pointed to the

normalised data so that prediction could be initiated.

Any errors during the pre-processing, training and

the actual prediction activities were stored in

individual log files which could be viewed at a later

point in time.

Figure 1: Knowledge creation captured within artificial

intelligence neural networks.

The GUI gave the option to the user to initiate

the Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP)

message. The message body was instantiated with

UsingKnowledgeManagementToolsandTechniquestoIncreasetheRateofAttendanceatBreastScreening

345

reference to an eXtensible Markup Language (XML)

schema definition designed on the Health Level 7

version 3 standards. The message was called upon

by the software to generate the SOAP envelope and

attached the XML message to the SOAP body with a

digital signature (for security). The Java-based web

services technology provided encryption to make the

message completely secure. The message was

transmitted via web services to the general

practitioner’s mailbox server.

Once the doctor’s server connected with the

mailbox it downloaded the messages and

automatically updated the womens’ records with the

likelihood of non-attendance. Meanwhile the breast

screening service continued its routine process of

inviting women by dispatching an appointed letter

(with details of the screening date and time). General

practitioners were now aware of those women who

are likely to miss breast screening appointments. If

those women visit the doctor for other services the

doctor can initiate an opportunistic intervention,

thereby increasing the likeliness of improving

screening uptake.

The second approach relied on knowledge

generated through a bespoke software program

written to capture non-attendees from results

generated by the National Breast Screening

Software. The prototype

framework incorporated the artificial intelligence

model for creating a list of predicted non-attending

women. The screening service produced the results

of the screening activity and used a report template

to export the batch list. The user (via GUI) pointed

to the location of the flat file to segregate the non-

attendees. Once segregation was complete, a new

message was generated using the same procedure as

before and it was sent to the respective general

practitioners. This updated the women’s medical

records with their non-attendance. The prototype

combined the demographic data pertaining to the

non-attending women and sent this information to

the General Practitioner as a messaging package.

The package triggered the generation of an

electronic message based on the Health Level 7

version 3 standards and utilised Service Orientated

Architecture as the message delivering technology.

The system has been designed in a way that will

enable it to be integrated into the UK health system.

Both approaches relied on the ability of the general

practitioner to intervene once women had been

identified as having characteristics that had been

shown to be associated with non-attendance.

Stage one of the project used quantitative

techniques to establish that non-attendance can be

predicted. The results can be shared with healthcare

providers in order to target interventions at women

who have characteristics associated with non-

attendance and overcome some of the barriers that

they face.

As the data collected in stage one was

impersonal (in addition to being anonymised),

personalised (human) components such as personal

apprehension, ethnicity-based influences, age-based

factors, personal economic circumstances and socio-

cultural factors also needed to be considered. To

address these “softer” issues and in order to

triangulate the results (from a qualitative

perspective), the use of focus groups was a natural

evolution of this study. In order to explore these

aspects further, two focus groups were carried out

(which straddled a detailed questionnaire).

Stage Two: (Qualitative) First Focus

Group

The information from the analysis of the records was

used to form a list of topics for discussion in the first

focus group, the aim of which was to identify

barriers to breast screening attendance. Participants

for the focus groups and questionnaire were clients

of Age UK, an organisation that aims to improve the

lives of older people (Age UK, 2013). Data from the

focus groups was analysed using thematic analysis

as described by Aronson (1994).

Stage Three: (Quantitative)

Questionnaire

The results of the initial focus group were compared

to the literature review and used to form a

questionnaire, using a technique described by Hoppe

et al. (1995) and Lankshear (1993). The aim of the

survey was to find out whether the views expressed

by the small number of people in the focus group

were shared by a larger and more representative

sample.

Stage Four: (Qualitative) Final Focus

Group

A second focus group discussed ways of tackling the

barriers to screening that had been identified.

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

346

4 RESULTS

Stage One: Analysis of Screening

Records

Data mining techniques were used to analyse records

from the local breast screening service. The valid

records constituted 86% (n=159,405) of the

extracted dataset. From 2002, women in the age

range 65-70 had an uptake of 70%. The efficiency of

the program can be mapped to attendance and the

number of non-attendees has been increasing so that

it has now reached half a million. Simple projection

of this data suggests that nearly 4,000 cancer

incidences would have been missed due to non-

attendance. A literature review identified factors that

have been shown to be associated with non-

attendance and for this reason analysis of the records

focused on key fields like Townsend Deprivation

Score, postcode and distance that women travelled

to a screening appointment.

Stage one of the current study produced bespoke

software developed within an open source

environment that was able to use demographic data

to identify individuals who were likely to face

barriers to attendance. Sharing this knowledge with

primary care enabled health professionals to deliver

interventions that helped the women make informed

decisions about whether to attend screening.

Stage Two: First Focus Group

Six participants took part in the first focus group.

They were five women and one man, with ages

ranging from 45-87 years. They all stated that their

ethnicity was English or British and they were either

retired or a housewife. Participants were asked why

they thought some women did not attend breast

screening and a variety of possible reasons were

discussed. Three main themes were identified and

the results will be presented under headings related

to these.

Communication Problems

The theme of communication problems incorporated

sub-themes of people not understanding English,

people being hard of hearing and people not

understanding medical terms.

The group thought interpreters and/ or

representatives from the patient’s community should

be available to support people who do not

understand English. It was also suggested that in

order to tackle all the forms of communication

problems, health professionals should avoid using

jargon and check that they have been understood.

Transport Problems

Public transport was thought to be unreliable,

journeys often took a long time and participants

were reluctant to ask other people for lifts. One

participant had used hospital transport and thought it

would be helpful to raise awareness of this service.

Reasons Associated with Beliefs and

Attitudes

Three sub-themes were identified: embarrassment,

anxiety and not realising the importance of

screening. The group thought that older people were

more likely to be embarrassed about having to

undress for examinations than younger people and

people with a cultural background that emphasised

female modesty might find screening examinations

particularly difficult.

It was clear that there was no single reason for

the anxiety that many women experience in relation

to screening. Two participants who had not yet been

invited to attend screening were anxious because

other people had told them that the procedure was

painful. Other group members had first-hand

experience of painful breast examinations and this

made them reluctant to return. One woman had

extensive scarring on her chest that made screening

unbearable. It was suggested that professionals

should acknowledge that the procedure could be

uncomfortable and offer ultrasound scans where

appropriate. The anxiety about receiving a positive

result was also discussed and it was also suggested

that some people might be unaware of the value of

screening.

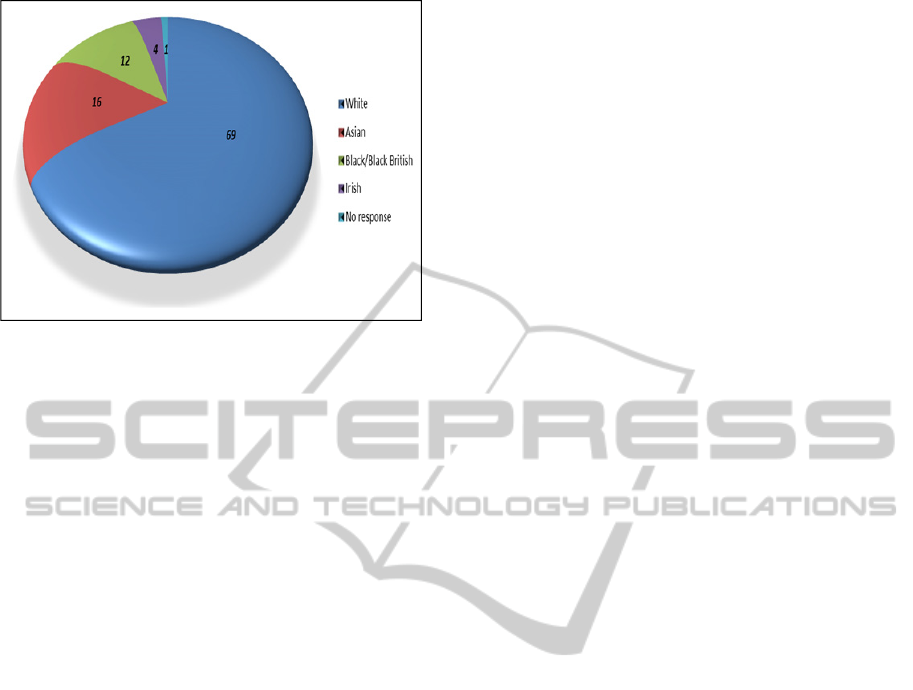

Stage Three: Questionnaire

147 questionnaires were given out and 102 were

completed, giving a response rate of 69%. 93

women and 9 men completed the questionnaire and

their average age was 65. Although the majority (69)

stated their ethnicity to be White British, 16% were

from an Asian Background and 12% were from a

Black background. People from an Asian

background make up 12% of Coventry’s population

and people from a Black background make up 3%

(Coventry Link, 2012). These are the largest

minority groups in Coventry and were well

represented in the survey. The pie chart (see figure

two) shows the ethnic origins of the survey

participants. Four Irish people took part in the

UsingKnowledgeManagementToolsandTechniquestoIncreasetheRateofAttendanceatBreastScreening

347

Figure 2: Pie chart comparing the ethnic origins of the

participants in the questionnaire survey.

survey and one participant did not answer the

question about ethnic origin.

75% of the participants had been invited to

attend screening and only four had not done so.

Their reasons for non-attendance were: the

appointment being at an inconvenient time, being

afraid of X-rays, not wanting to get a cancer

diagnosis and being put off by adverse publicity

about over-diagnosis.

78% of the participants thought problems with

communication might be a reason for non-

attendance. They suggested having more

interpreters, providing the information in different

languages, strengthening links with local

communities and improving the communication

skills of professionals.

56% of the participants thought that difficulties

getting transport would affect attendance. Solutions

included having more mobile units and holding

screening at locations convenient for users of public

transport.

11% of the participants thought that embarrassment

might put women off attending screening. They

thought creating links with local communities and

reassuring women that screening is carried out by

female professionals would help.

Anxiety about the procedure or the possibility of

receiving bad news was the most common reason

that participants gave for non-attendance, with

exactly 50% of the participants mentioning anxiety.

Eleven of the participants said that having more

information about the procedure would be useful.

The use of television to educate people about what

happens and providing a helpline where women can

ask for more information were suggested. Two

participants thought the recent bad publicity about

over-diagnosis might make some women reluctant to

attend and three participants thought that some

women might not appreciate the importance of

screening.

It was clear from both the focus group and

questionnaire results that anxiety was not a single

factor but included concerns about the procedure

(including ignorance about what was involved and

concerns that the procedure would be painful) and

anxiety about receiving a cancer diagnosis.

Educating people about the procedure was suggested

as a way to reduce anxiety. It was also suggested

that the service should balance recent negative

publicity about over-diagnosis with positive stories

of how early diagnosis and treatment can enable

cancer to be treated while it is still at an early stage.

The results from the questionnaire and the focus

group informed the discussion that took place in the

final focus group, the purpose of which was to

suggest ways in which the barriers to screening

could be overcome.

Stage Four: Final Focus Group

Five participants took part in the group. They were

all women and their ages ranged from 54-77.

Communication Problems

One of the group suggested having more interpreters

available and another pointed out that people often

have cultural barriers to overcome in addition to

language barriers. Suggestions of how these could

be tackled included promoting screening at women’s

groups and encouraging community elders to

support the program.

It was noted that it is not always obvious if

people have difficulty hearing. Health professionals

should be aware that this might be the case and

check that they have been understood. Several group

members had experienced being unable to

understand the terms used by professionals and

thought it would help if familiar language was used.

Transport Problems

Although providing transport was suggested, this

was thought to be expensive and ensuring that

screening is carried out in locations convenient for

public transport was suggested as a more realistic

solution. It was also thought to be important to offer

appointments at a range of times, including

evenings, to make these convenient for the service

users.

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

348

Beliefs and Attitudes

Participants thought that creating links with

communities would help women to feel comfortable

about attending screening. Two participants thought

it was important for screening to be carried out by

female professionals and for potential clients to be

made aware of this. It was suggested that women

should be encouraged to ask professionals about

screening so they get accurate information and

reassurance. One participant who had been

successfully treated for breast cancer as a result of

this being picked up at screening thought women

who had similar experiences would be good at

persuading others of the importance of screening.

5 LIMITATIONS

A local sample of participants was used in the study

and it is not clear how far the results can be

generalised to other areas of the country. Although

care was taken to ensure that the participants were

representative of the local population of older adults,

there are ways in which people who attend Age UK

meetings may differ from those who fail to attend

breast screening. Those who attend the meetings are

able to arrange transport to do so and it can be

assumed that they will also be able to arrange

transport to attend screening. People attending

activities organised by Age UK are also interested in

their health and in socialising. These characteristics

may not be shared by people who fail to attend

screening. It is clear that ethnicity and family

support are factors affecting attendance. Women

who do not speak English, rarely socialise outside

their community and have family responsibilities

that make it difficult for them to attend appointments

may also be unlikely to be involved with the type of

activities offered by Age UK.

6 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

PRACTICE

It is clear from the results that the barriers to breast

screening attendance are varied and include social

influences like family support and psychological

factors such as anxiety. It is likely that women who

do not attend screening face a combination of

barriers. Contemporary approaches like knowledge

management offer a means by which intelligence

about individuals can be shared between primary

care and the breast screening service, in order to

identify women who may face barriers to

attendance. Targeted interventions, such as

providing information in their own language can

then be deployed.

The main barriers to breast screening attendance

that were identified during the study included those

associated with communication. Problems getting

transport to appointments was also a barrier but the

most common reason for non-attendance was

thought to be anxiety. This ranged from concern that

the procedure would be painful to being afraid of

receiving bad news. In common with a recent local

study (Coventry Link, 2012), many participants

thought that there was a lack of knowledge about

screening and that educating people about its

importance and what is involved would increase

attendance rates. The results of the current study

suggest that attendance could be improved by:

Providing invitations and information about

screening in simple language and in

different languages where appropriate

Having interpreters and community

representatives available to support women

at appointments

Ensuring screening is carried out at

locations that are easy for women to get to

by public transport

Creating links with local communities,

educating people about screening and

encouraging them to talk to professionals

about their concerns

Publicising stories of women who have

been successfully treated for breast cancer

as a result of being diagnosed early

It will be important to evaluate the effect of these

initiatives on attendance rates.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Baskaran (2008) identified individual characteristics,

such as age, ethnicity and socio-economic status that

were associated with breast screening non-

attendance. This study demonstrated that such

characteristics could be used to predict non-

attendance and provide health professionals with the

opportunity to carry out interventions, such as

ensuring information is provided in a language that

will be understood by potential participants.

The current study identified additional barriers to

attendance that were concerned with

UsingKnowledgeManagementToolsandTechniquestoIncreasetheRateofAttendanceatBreastScreening

349

communication, transport, beliefs and attitudes. The

results were similar to another local study (Coventry

Link 2012) which considered barriers faced by

people from ethnic minority backgrounds when

trying to access screening services. Both studies

identified communication problems, transport

problems and attitudes as barriers to attendance. The

recommendations that were formed from the results

of the current study provide suggestions of

interventions that would be expected to increase

screening attendance rates.

Future work should include evaluating the effect

of the suggested interventions on the attendance rate.

Research should also be carried out in other areas of

the country to see how far the results can be

generalised.

REFERENCES

Age UK (2013) [online] Available from

<http://www.ageuk.org.uk/> [3rd March 2013].

Aronson, J. (1994) “A pragmatic view of thematic

analysis.” The Qualitative Report 2 (1) [online]

Available from <http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR

/Backissues/QR2-1/aronson.html> [28 March 2010].

Atri, J., Falshaw, M., Gregg, R., Robson, J. Omar, R.Z.

and Dixon, S. (1997) “Improving uptake of breast

screening in multiethnic populations in a randomised

controlled trial using practice reception staff to contact

non-attenders.” BMJ 315, 1356-9.

Bali, R.K., Wickramasinghe, N. and Lehaney, B. (2009)

Knowledge Management Primer, Routledge: USA.

Bankhead, C., Austoker, J., Sharp, D., Peters, T.,

Richards, S.H., Hobbs, R., Brown, J., Wilson, S.,

Roberts, L., Redman., Tydeman, C., Formby, J. (2001)

“ A practice based randomised controlled trial of two

simple interventions aimed to increase uptake of breast

cancer screening.” Journal of Medical Screening 8, (2)

91-98.

Baskaran, V. (2008) Implementation of a breast cancer

screening prediction algorithm: a knowledge

management approach, PhD thesis. Coventry

University.

Bekker, H., Morrison, L., and Marteau, T.M. (1999)

“Breast Screening: GP’s beliefs, attitudes and

practices.” New York: Basic Books.

Cancer Research UK (2005) CancerStats Incidence-UK

[online] Available from www.cancerresearchuk

.org/aboutcancer/statistics/statsmisc/pdfs/cancerstats_I

ncidence_apr05.pdf, [August 2005].

Cassandra, E. S. (2006) “Breast cancer screening: cultural

beliefs and diverse populations.” Health and social

work 31, (1) 36-43.

Coventry Link (2012) Accessing Cancer Screening

Services for People from ethnic minority communities

in Coventry, Coventry Link.

Day, N.E., Williams, D.D.R., Khaw, K.T. (1989) “Breast

cancer screening programmes: the development of a

monitoring and evaluation system.” British Journal of

Cancer 59, 954-8.

Fox, S., Murata, P. and Stein, J. (1991) “The impact of

physician compliance on screening mammography for

older women.” Arch. Internal Medicine 151, 50-56.

Hoppe, M. J., Wells, E. A., Morrison, D. M., Gilmore, M.

R., and Wilsdon, A. (1995) “Using Focus Groups to

Discuss Sensitive Topics With Children.” Evaluation

Review 19 (1), 102-14.

Jepson, r., Clegg, A., Forbes, C., Lewis, R., Sowden, A.

and Kleijnen, J. (2000) “The determinants of screening

uptake and interventions for increasing uptake: a

systematic review.” Health Technology Assess 4, (14)

Katz, S.J., Zemencuk, J.K., Hofer, T.P. (2000) “Breast

cancer screening in the United States and Canada,

1994: Socioeconomic Gradients Persist.” American

Journal of Public Health, 90, (5) 799-803.

Katz, S.J., Zemencuk, J.K., Hofer, T.P. (2000) “Breast

cancer screening in the United States and Canada,

1994: Socioeconomic Gradients Persist.” American

Journal of Public Health, 90, (5) 799-803.

Lankshear, A. J. (1993) “The Use of Focus Groups in a

Study of Attitudes to Student Nurse Assessment.”

Journal of Advanced Nursing 18, 1986-89.

Sin, J.P. and Leger, A.S. (1999) “Interventions to increase

breast screening uptake, do they make any

difference?” Journal of Medical Screening 6, (1) 170-

181.

Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A. (1988) Health and

Deprivation: Inequality and the North Croom Helm:

London.

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

350