Business Ontologies Modelling for Communities

of Handicraft Women

Valérie Monfort

1,2

, Ikmel Haamdi

1

, Rahma Dhaouadi

1

and Achraf Benmiled

1

1

SOIE LI3, ISG Tunis, 41, Rue de la Liberté, Cité Bouchoucha 2000 Le Bardo, Tunis, Tunisia

2

Université de Paris 1, Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris, France

Abstract. Social networks are websites or platforms which bring together users

in various online communities. Social networking on the Internet capitalizes on

the Web’s latent structure as a meta-network of social connections to boost

computer-supported collaboration in conjunction with the use of Semantic Web

metadata. The Semantic Web effort is in an ideal position to make Social Web

sites interoperable. Applying Semantic Web frameworks including SIOC (Se-

mantically Interlinked Online Communities) and FOAF (Friend-of-a-Friend) to

the Social Web can lead to a Social Semantic Web, creating a network of inter-

linked and semantically rich knowledge. Moreover, communities can be profes-

sionals who want to share knowledge, to sell their production, to communicate

and to collaborate. We are involved in a research project which aims to study

the ability of handicraft women to use new technologies. In this paper, we show

the manner we elicit and we model knowledge with several business ontologies.

1 Introduction

A Social Network is usually formed by a group of individuals who have a set of

common interests and objectives. There are usually a set of network formulators fol-

lowed by a broadcast to achieve the network membership. After the minimum num-

bers are met, the network starts its basic operations and goes out to achieve its goal.

Success of a Social Network mainly depends on contribution, interest and motivation

of its members along with technology backbone or platform support that makes the

life easier to communicate and exchange information to fulfil a particular communica-

tion need. Moreover, the social-semantic web (s2w) [1] aims to complement the for-

mal Semantic Web vision by adding a pragmatic approach relying on description

languages for semantic browsing using heuristic classification and semiotic ontolo-

gies. A socio-semantic system has a continuous process of eliciting crucial knowledge

of a domain through semi-formal ontologies, taxonomies or folksonomies. S2w em-

phasize the importance of humanly created loose semantics as means to fulfil the

vision of the semantic web. Instead of relying entirely on automated semantics with

formal ontology processing and inferring, humans are collaboratively building seman-

tics aided by socio-semantic information systems. While the semantic web enables

integration of business processing with precise automatic logic inference computing

across domains, the socio-semantic web opens up for a more social interface to the

Monfort V., Hamdi I., Dhaouadi R. and Ben Miled A..

Business Ontologies Modelling for Communities of Handicraft Women.

DOI: 10.5220/0004608500520062

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Web Intelligence (WEBI-2013), pages 52-62

ISBN: 978-989-8565-63-1

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

semantics of businesses, allowing interoperability between business objects, actions

and their users. Much of the Semantic Web functionality envisioned by Tim Berners-

Lee [2] relies on ontologies [5] [10]. Creating ontologies is difficult, time-consuming,

and expensive, reminding of the labor of knowledge engineering in expert system

design, in particular if ontologies are designed to support automated inference envi-

sioned by advanced Semantic Web applications.

Our research work is based on a research project studying the manner handicraft

women use new technologies such as social networks to develop their activity. In a

first time, we aim to elicit knowledge and to model ontologies with Protégé Tool. The

aim of this paper is to present an extract of this first step and how we organized to

succeed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduced the con-

text of the project. A brief state of the art on ontologies is given in section 3. Section 4

describes approaches to define ontologies. In section 5 we propose an extract of the

Handicraft ontologies. Conclusion is given in section 6.

2 Context

2.1 Landscape

The users want to keep in touch with friend regardless of the Host location. They are

able to share their interest by joining groups and forums too. Some social media might

help people find jobs and may even help establish business contacts. Social networks

offer special features such as the choice to design their profiles that reflects their per-

sonality or emotion. Music and video sections are also popular additional features.

Social networks are examined through the profiles they provide, the safety it provides

to the people, networking features their people may use, search option, support and

help choice for any queries through the people, plus much more. Myspace is among

the best internet sites for locating people. Although Facebook profiles can't be person-

alized, their platform is extremely clever and clean. Facebook is centered on interac-

tions. Specifying extracted knowledge from interviews under ontology formalism is a

primordial step. But the structure of the generated ontology still static without any

enhancement procedures. However exploring social networks data and structure can

leads us to deduce relevant scenarios to ensure the dynamicity of the already designed

ontology. On top of all, with our pragmatic experience and drawback, we noticed

three main lacks addressed below:

- The major challenges come from the fact that social networks in the present age

do not concentrate on a particular service. Every social network tries to provide

maximum features to its users. Social networks are slowly losing out on the user

population who are finding it very difficult to concentrate on a particular social

network for a length of time. The increasing competition is also removing the

most important feature of these networks. We propose a social network should be

concentrating upon one of the niche services while keeping the other common fea-

tures as an additive or supporting cast to the main service.

53

- Semantics emerged from social networks. We think also that specific ontologies

for social networks such as FOAF

1

, RELATIONSHIP

2

, SIOC

3

, MOAT

4

, and

SKOS

5

are a possible issue to model profile, etc. But these ontologies do not allow

us to model business knowledge (data, process, etc). Moreover, these ontologies

are limited for instance, profile express the semantics of a user profile not a social

Web user involved in a professional activity, sharing a part of his/her knowledge

to some members, collaborating to propose a specific product, learning technics

from other members, etc. We propose to align different kind of ontologies to face

to the different point of views.

- The resources allocation shows a genuine lack of flexibility, we aim to address

this lack at run time as communities are endlessly creating and re configuring. We

propose to use specific graphs theory issues.

2.2 Project Description

We are involved in a research project financed by both the Tunisian and Algerian

governments. The aim of this project is to study the manner handicraft women use

new technologies to support their activity. The main characteristics of these commu-

nities are as followed:

- Women come from different Tunisian and Algerian regions. The priority of the

governments was to favour touristic and along the coast big cities, to the detriment

of inland regions. So inland infrastructures are archaic, and unemployment is in-

creasing.

- Inland Handicraft women are mostly coming from poor social background and

they have the duty to stop studying early to financially help their family. Most of

them are analphabetic housewives with several children and with unemployed

husband. This provides the social, traditional, religious and cultural backgrounds

with the perfect ground upon which to impose their supremacy. Simply using a

mobile phone might be seen as an emancipation act, so, very often, husband uses

phone instead of his wife.

- It is difficult to contact raw material providers who rarely sell little quantities. It is

also difficult to sell their production, because they are isolated and they need

means of transport. Organized associations mostly are lucrative and make a con-

sequent profit to the detriment of Handicraft women.

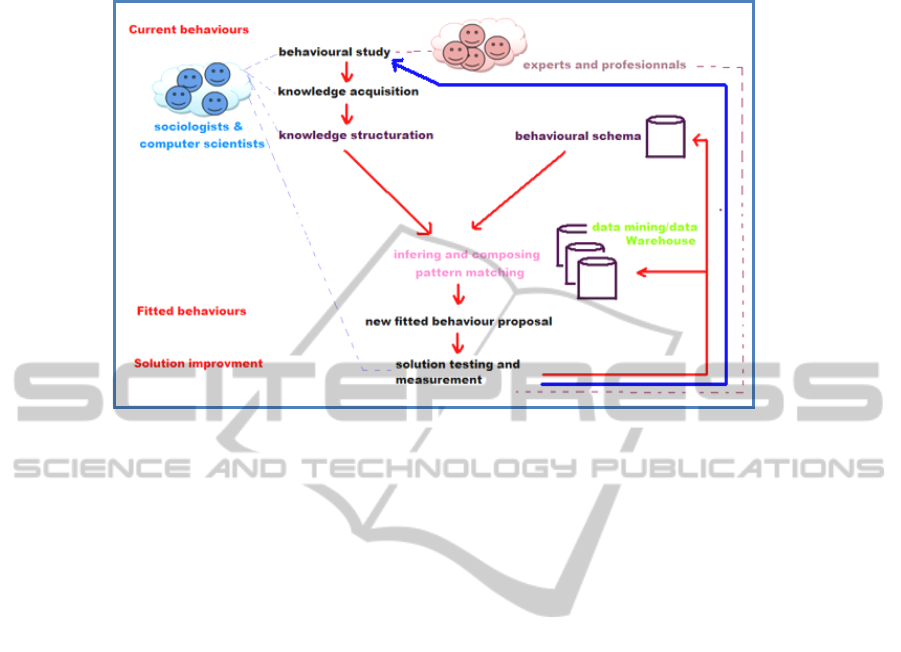

Firstly, we aim to study the manner handicraft women use technologies (Fig.1). We

plan to propose them specific training with specific semi assisted organization to help

them. Then, we shall study their learning skills. Some will not accept and will propose

their children to be trained. These results will help us to define a genuine social pro-

file of these women and to challenge current communication technologies. We aim to

answer to the following question: Are current communication technologies suitable to

all the users?

1

http://www.foaf-project.org/

2

http://vocab.org/relationship/

3

http://sioc-project.org/

4

http://moat-project.org/ns#

5

http://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/

54

Fig. 1. Proposed process.

Secondly, we aim to develop handicraft women activities allowing them gaining their

independence and increasing their purchasing power. To meet such a goal we propose

to create communities sharing together the knowledge, the experience and the creativ-

ity regarding handicraft activities. This will be very helpful when dealing with collab-

orative work promotion or training other women to handicraft jobs which results in

reducing unemployment rate.

Our team includes socio economists and computer scientists. Socio economist

members defined an interview grid. We found facilitators to meet women. We started

driving interviews to design knowledge which are formalized via ontologies to ex-

press: business data (clay, clay color, quantity of clay, paintbrush, natural pigment,

wool, etc), business processes (providers selection, production, clay cooking, selling,

etc), and business rules (“when ambient temperature is over 18°C drying time of clay

is 2 days”). According to ambient context, women’s skills and profile can change

and/or be adapted according to profiles or geographical location.

3 Knowledge and Ontologies

Knowledge acquisition is the ability to locate, gather, and formalize knowledge. This

process is often named knowledge management and is dealing with two distinguished

knowledge nature explicit knowledge and tacit one [12]. There are previous steps to

overcome before focusing on the identification of relevant knowledge belonging to a

contextualized domain which are collecting data and then structuring and organizing

this obtained data so to be already information. Several approaches are proposed such

as positivist and constructivist. Positivist approach assumes that knowledge is com-

pletely independent on a user or on a group of users while the knowledge extraction

phase is done partially. However constructivist approach is considering that

55

knowledge is built step by step in a collective way and is the resulting from the study

and validation of information by the domain expert community. Knowledge mapping

is composed of three phases: 1) Context analysis through the domain experts inter-

viewing. 2) Collective appropriation of relevant information carried out by experts. 3)

Information validation and information recognition by experts and potential users. We

are especially interested in the acquisition of business knowledge regarding tech-

niques, practices and skills required to design and realize a specific handicraft prod-

uct. In the following, we are mentioning five approaches for business knowledge

management:

- The Social and cooperative approach consists in the study of the interactions be-

tween group members thus to offer tools and methods to structure and enhance

exchanged knowledge and facilitate the reuse.

- The Bottom-up approach consists in identifying and extracting concepts and the

reasoning of the domain taking into account sources like deliverable, reports,

emails, etc.

- The Top-down approach consists in a first of all in mapping the domain

knowledge and then the system or the cogniticians interact with experts in order to

extract the necessary information.

- The Decisional approach consists in the knowledge capitalization and reuse in

order to support the decision making.

- The Organisational approach takes into account the social dimension in order to

structure knowledge and especially to facilitate the share of formalized knowledge

among. New technologies can support this fact.

This knowledge is structured into ontologies. According to [13], we can classify on-

tologies as followed: 1) The generic or upper ontology is specifying common abstract

concepts subsuming the terms belonging to a wide range of domain ontologies. It can

be applicable in various contexts; 2). The domain ontology is only specifying

knowledge related to a specific one particular domain such as medicine, agronomy,

policy, GIS etc. Another relevant definition is given in [9], where authors assert that

domain ontology models the information known about a particular subject and there-

fore should closely match the level of information found in a textbook on that subject;

3) Business ontology: It is focused in the formalization of the knowledge regarding a

specific business. It is dealing with actors, resources, processes defining this business.

4) Task ontology or process ontology: it describes the vocabulary specific to a task or

an activity integrated in the completion of a determined final target. Besides, this

ontology specifies a reasoning process towards a specific goal. 5) Application ontolo-

gy: It is dedicated to a specific application and it includes enough knowledge to struc-

ture a particular domain. An additional dimension when applied to ontology is ena-

bling the transfer from static ontology structure to a dynamic one ensuring its evolu-

tion online. This dimension is always called context, situation or simply environment

and is very useful mainly to support decision making respectively to contextual

changes.

Abstract, business and task ontologies with instances are used in the handicraft

women’s project. We aim to define different abstraction levels such as: 1) a generic

level which is the same for all handicraft business, 2) a business level for one specific

handicraft business such as ceramic, 3) an instance level to create detailed typologies

such as the categories of ovens (electric, with wood, etc). Several operations such as

56

alignment or merging can be applied to the ontology: 1) Alignment principle is con-

sisting in the identification of semantic matches between the elements (concepts, their

relationships, their instances) belonging to different ontologies [

6]. The alignment

process is based in the mapping process and is stopped with setting the necessary

association between entities belonging to the different ontologies. 2) However, ontol-

ogy merging procedure [11] consists in the fusion of the set of handled ontologies in a

united one. This generated ontology includes: concepts, relationships and instances of

original ontologies.

According to [2], two main groups of approach to build ontologies can be identi-

fied. On the one hand, there are experience-based methodologies, such as the meth-

odology proposed by [3] based on TOVE Project or the other exposed by [4] from

Enterprise Model. Both were issued in 1995 and belong to the enterprise modeler

domain. On the other hand, some methodologies propose flexible prototypes models,

such as METHONTOLOGY [7] that proposes a set of activities to develop ontologies

based on its life cycle and the prototype refinement; and 101 Method [8] that propos-

es an iterative approach to ontology development. On the one hand, there is not just

one correct way or methodology for developing ontologies. Usually, the first ones are

applied when the requirements are clearly known at the beginning; the second ones

when the objectives are not clear from the beginning. Moreover, it is common to

merge different methodologies since each of them provides design ideas that distin-

guish it from the others. This merging depends on the ontology users and ontology

goals. On the other hand, like any other conceptual modeling activity, ontology con-

struction must be supported by software engineering techniques. Thus, we used meth-

ods and tools from software engineering to support ontology engineering activities.

Ontology development can also be divided into two main phases: specification and

conceptualization. The goal of the specification phase is to acquire informal

knowledge about the domain. The goal of the conceptualization phase is to organize

and structure this knowledge using external representations that are independent of

the implementation languages and environments.

Manual approaches for modeling ontologies are costly and time consuming.

Moreover, semi automatic or automatic methods are mostly used. They are always

handling unstructured data like textual documents. Multiple methods are based on

techniques of natural language treatment combined with machine learning tools.

However, according to social profile of women we used manual approaches. Some

women are analphabet, shy, and they are very impressed by researchers which interest

on their activity. So we used, questions, pictures, documents, films, etc, to define and

model knowledge.

4 Proposed Ontologies

4.1 A Business Generic Ontology

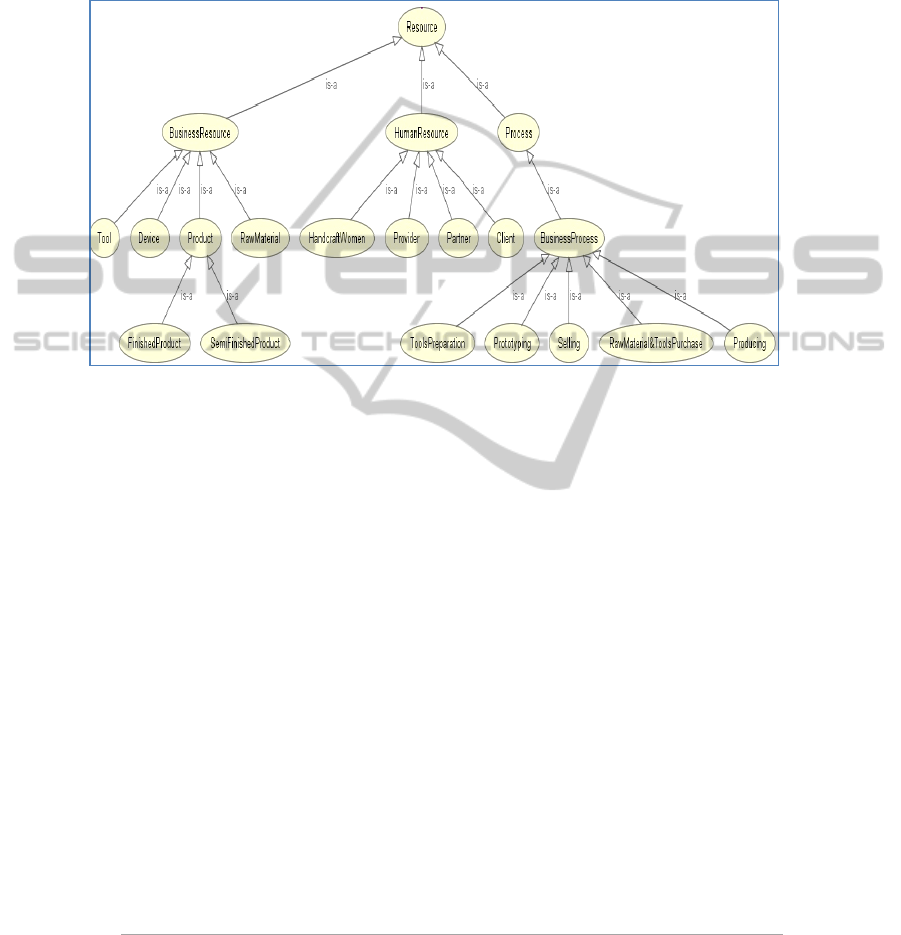

Figure 2 is an implementation with Protégé 4.2

6

and presents an ontology to describe

the semantic relation between women, the whole environment and context. Protégé

OWL plugin is used to define an OWL ontology representing the resource relation-

ships combined with SWRL

7

(Semantic Web Rule Language) and representing the

57

dependencies between those relationships. There modeled three kinds of resources: 1)

Human resources include: women, clients, providers and partners which help to prod-

uct. 2) Business Process describes women activity and what they use for. 3) Process is

very important for the production, selling and purchasing cycle. Following ontology

(Fig 2.) is supposed to be the same for all the handicraft business.

Fig 2. A Business Generic ontology.

4.2 A Business Specific Ontology

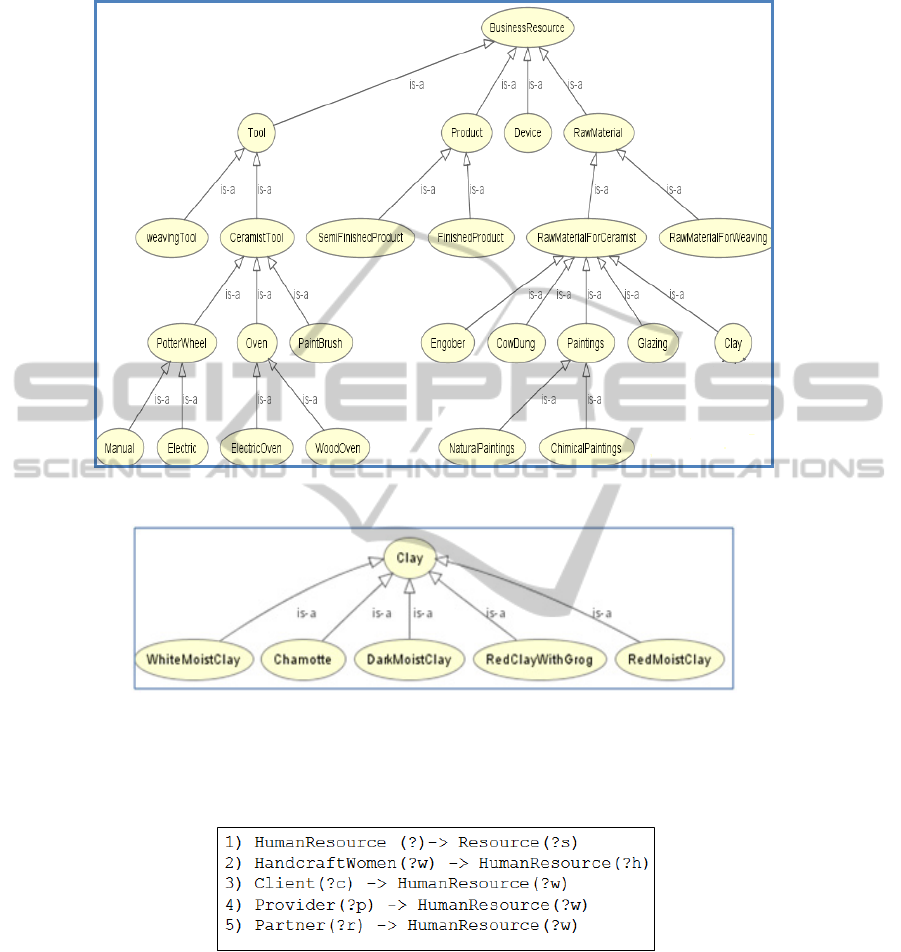

Figure 3 shows one kind of women’s work, it’s composed of tools and raw material.

During the production step women need tools and raw material. This ontology de-

scribes a ceramic product: women uses a pottery wheel (manual, electric), oven (elec-

tric, woody) and paint brush. The raw materials are: engober, dried cow dung, paint-

ing (chemical and natural), glazing and clay.

4.3 A Business Instance

Figure 4 shows an instance from the clay entity. Depending on the production women

choose a particular kind of Clay such as: chamotte, white clay or red clay.

There are several kinds of clay such as: WhiteMoistClay, Chamote, RedClay, etc.

They are all instances of clay.

A SWRL rule contains body and a header. Both the

body and head include positive conjunctions of atoms:

atom ^ atom .... - > atom ^ atom (1)

An atom is an expression where p is a predicate symbol and arg1, arg2... argn are

the terms or arguments of the expression:

p (arg1, arg2, ... argn) (2)

6

http://protege.stanford.edu/

7

http://www.w3.org/Submission/SWRL/

58

Fig 3. A Business Specific ontology.

Fig 4. Instances.

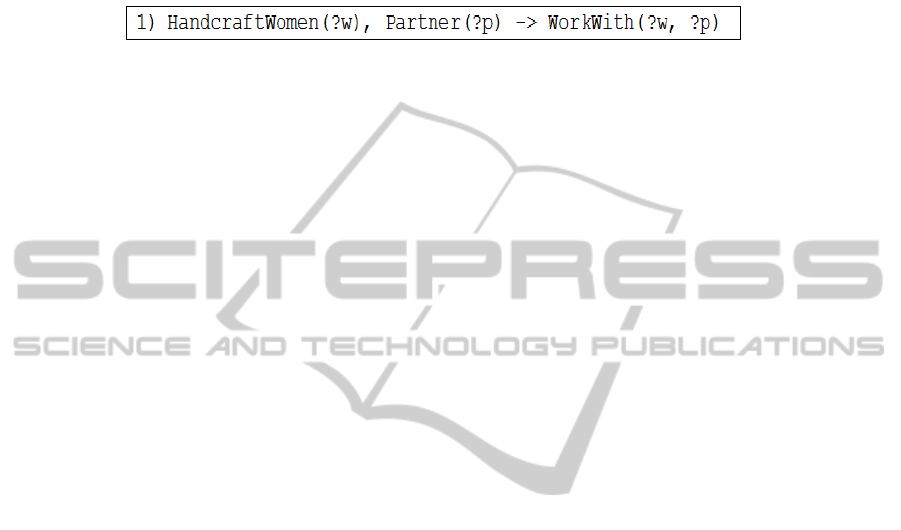

Code1 presents some rules created with SWRL.

Code 1. Hierarchy of Business entities.

According to the first rule (line 1) of code1, human resource is a sub class of Re-

source. Women, clients, providers and partners are sub class of HumanResource.

Code 1 shows an example rule using class atoms to declare types of women, clients,

partner and provider are part of the class HumanRessource.

A second rule (Code 2) shows women use their devices to contact suppliers, part-

ners and clients: The rule contains three atoms, which is expressed by the relation

59

between women, partner, provider and client. Here, HandcraftWomen and Partner

are OWL named classes, (?w) is a variable representing an OWL individual.

UseDevice and Contact are OWL object properties. Women can contact Partners,

providers or clients.

Code 2. Rule To use device to contact different actors.

This rule illustrates women use devices during the selling and purchasing process:

Here,

HandcraftWomen and RawMaterial&ToolsPurchase are OWL named

classes.

UseDevice and Purchase are OWL object properties. According to this

rule, women can access to User Interface via their devices to purchase (

Purchase)

raw material and tools (line 1). They also can sell (

SellProduct) their Product

(

FinishedProduct) using their devices (line 2).

Code 3. Rule To use device to contact different actors.

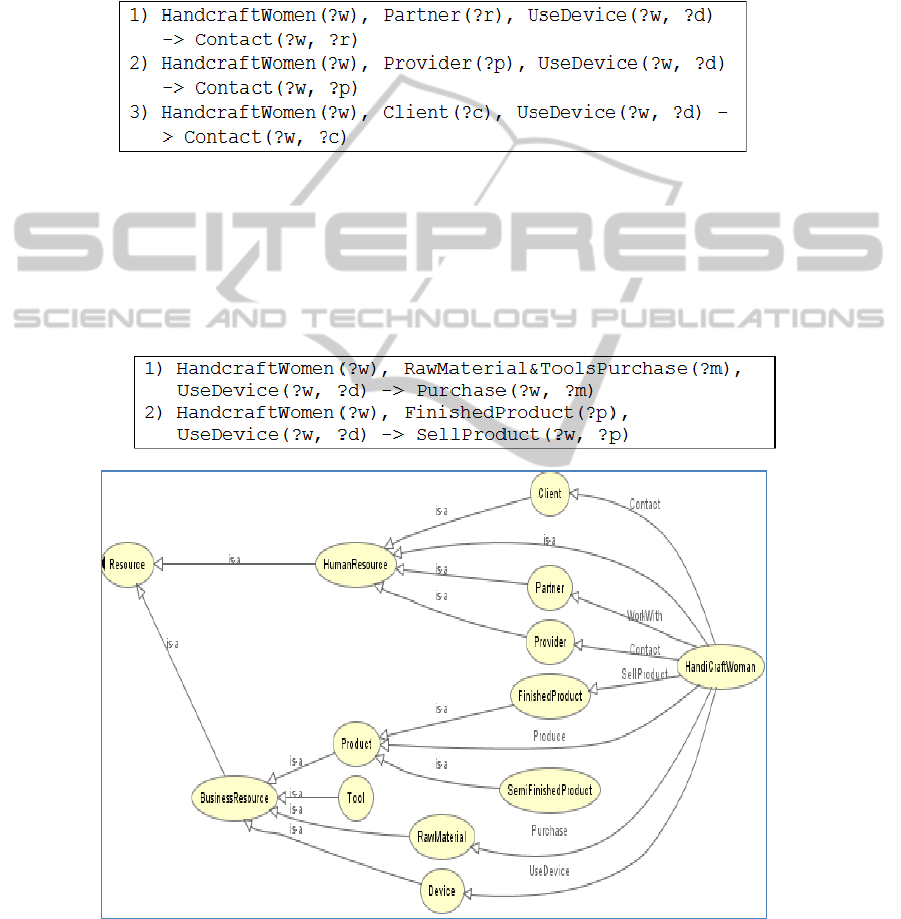

Fig 5. Graph presenting ontologies and relations.

60

Production process can be shared by two handicraft women (code 4). Here, Hand-

craftWomen and Partner are OWL named classes. WorkWith is an OWL object

properties. Another rule allow choosing to work with a partner (

WorkWith).

Code 4. Rule To access to women partners.

The graph of the fig.5 is an extract and it presents elements and relationships between

concepts.

6 Conclusions

Our work is based on a research project studying the manner handicraft women use

new technologies such as social networks to develop their activity. In a first time, we

aimed to elicit knowledge and to model ontologies with Protégé Tool. We met diffi-

culties to access to inland women who are living in little villages where roads are

more trails made of stones. But all the women accept interviews and to be trained (or

delegate their daughters). We go on interviewing and we plan to use social Web Min-

ing to analyze results. With trainings and next analysis, we hope having answer to the

suitability of new technologies to any kind of user. With this answer we could define

either a new technology either we shall adapt current technologies. We are faced to

the limitations mentioned in section 2.1 and we have to find solutions in future works

as the processes modeling and the execution of these ontologies.

References

1. Cahier J. P., L'Hédi Z., Zacklad M. : Information seeking in a "socio-semantic web" appli-

cation. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Pragmatic Web, ICPW, Simon

Buckingham Shum, Mikael Lind, Hans Weigand (Eds.):, ACM International Conference

Proceeding Series 280 ACM 2007, ISBN 978-1-59593-859-6, Tilburg, The Netherlands,

October 22-23 (2007)

2. Berners-Lee T., Fischetti M., Weaving the Web : The Original Design and Ultimate Desti-

ny of the World Wide Web by Its Inventor, New York, HarperBusiness, 2000, 256 p.

(ISBN 0-06-251587-X)

3. Wache H., Vögele T., Visser U., Stuckenschmidt H., Schuster G., Neumann H., Hübner S.

(2001) Ontology-Based Integration of Information –A Survey of Existing Approaches.

Proc. IJCAI-01 Workshop: Ontologies and Information Sharing, Seattle, WA, 108-117.

4. Gruninger M. and Fox M. S. (1995) Methodology for the Design and Evaluation of Ontol-

ogies, IJCAI Workshop on Basic Ontological in Knowledge Sharing, Montreal, Canada.

5. Gruber, Thomas R: A translation Approach to portable ontology specifications, knowledge

Acquisition: 199-220 (June 1993)

6. Jérôme Euzenat, Pavel Shvaiko: Ontology matching, Springer-Verlag, 978-3-540-49611-3,

(2007)

7. Gómez-Pérez A., Fernández López M. and Corcho O. (2004) Ontological Engineering

with examples from the areas of knowledge management, e-commerce and the semantic

web. London: Springer.

61

8. Fernández M., Gómez-Pérez A., Juristo N., «METHONTOLOGY: From ontological art

towards ontological engineering», Proceedings AAAI-97 Spring Symposium Series, Work-

shop on ontological engineering, Stanford (California), 1997, p. 33-40

9. Sinéad Boyce, Claus Pahl: Developing Domain Ontologies for Course Content. In Educa-

tional Technology & Society 10 (3): 275-288 (2007)

10. Corby O., Dieng-Kuntz R., Faron-Zucker C., "Querying the Semantic Web with Corese

Search Engine”, the 16th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ECAI’2004),

Prestigious Applications of Intelligent Systems, pages 705–709, Valencia, Spain, August

22-27, 2004.

11. Konstantinos Kotis, George A. Vouros, Konstantinos Stergiou: Towards automatic merging

of domain ontologies: The HCONE-merge approach. Web Semantics: Science, Services

and Agents on the World Wide Web, Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2006, Pages 60-79

12. Nonaka I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995): "The Knowledge-Creating Company", Oxford Univer-

sity Press, Oxford, 1995.

13. Guarino N. “Some Ontological Principles for designing upper level lexical resources” in

Proceedings of the first international conference on lexical resources and evaluation, 1998.

62