Learning in an Organisation

Exploring the Nature of Relationships

Karin Dessne

Swedish School of Information and Library Science, University of Borås, Allégatan 1, Borås, Sweden

Keywords: Informal Learning, Formal Learning, Relationships, Organisational Learning.

Abstract: Learning transpires in the relationships that shape an organisation, and the nature of them influences the

characteristics of this learning. To realise learning objectives it is necessary to know how features that

influence relationships may be provided and manipulated. The aim of this paper is to present a model of

preconditions that contributes to the nature of relationships in an organisation. The focus is to explore

preconditions contributing to the informal aspect of relationships. Another aim is to show that these

preconditions also influence the formal aspect of relationships. The contribution is a model for studying

some crucial preconditions related to learning in an organisation.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper proposes a model for exploring the nature

of relationships in an organisation. This nature of

relationships is reflected in the way people interact

and participate. The model concentrates on

preconditions for the emergence, growth and

existence of informal relationships. This model,

named the Precondition Profile Model, may also

assist an organisation to understand how to create or

alter features shaping the preconditions.

Organisations always provide – intentionally or

unintentionally – such preconditions. This fact

impacts on learning that is accomplished through

participating in social interaction. Based on this

impact claim, an organisation aiming to facilitate

beneficial learning needs to be aware of the nature of

relationships in order to know how it may respond to

various influences provided.

Formality and informality are two concepts often

used to explore relationships as well as learning in

an organisation. Relationships may be expressed as

structures or networks. A common division is to

refer to them as formal and informal structures. The

relationships formally created are designed by the

management of the organisation in order to carry out

work (e.g. Burns and Stalker, 1961, Conway, 2001,

Meyer and Rowan, 1977, Wang and Ahmed, 2002).

The relationships informally created emerge

between people co-participating in the workplace

(Wang and Ahmed, 2002, Brown and Duguid, 1991,

Conway, 2001). In reality, relationships often relate

to and depend on each other. The informal

relationships emerge within formally designed

relationships, and the designed relationships cannot

be designed in such detail to prohibit any kind of

informal emerging characteristics. It is therefore

more useful to address the idea of formal and

informal as aspects of formality and informality in

relationships. Still, they may be viewed as mainly

formal or informal.

An organisation is often seen as a social

construct where people are bound together by

various relationships (e.g. Diefenbach and Sillince,

2011, Ran and Golden, 2011). This means that the

nature of relationships encompasses informality

through emerging relationships as well as it

encompasses formality through designed

relationships. As aspects of formality and

informality in relationships interact with each other,

the preconditions claimed to be vital for informal

relationships are also important to formal

relationships.

Traditionally, much research has – similar to

formal and informal structures – studied learning in

isolation as either formal or informal. Formal

learning refers to designed learning such as for

example education in schools (Marsick and Watkins,

2001). Informal learning refers to the learning

carried out in social relationships (e.g. Wenger,

1998, Eraut, 2004). Nevertheless, no agreed upon

496

Dessne K..

Learning in an Organisation - Exploring the Nature of Relationships.

DOI: 10.5220/0004625604960501

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval and the International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2013), pages 496-501

ISBN: 978-989-8565-75-4

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

definitions of formal and informal learning are

provided in literature (Malcolm et al., 2003).

Rasmussen and Nielsen (2011) emphasise that

the approaches on learning as formal or informal are

not mutually exclusive but should be combined.

Thus they claim that the approach to learning should

focus on the integrated, and not on the isolated.

Rasmussen and Nielsen further argue that the point

is to achieve innovative performance in a dynamic

environment, and for this purpose, both formal and

informal learning need to be supported. If they are

both supported, the organisation can benefit from

them rather than suffer from a potential tension

between them (Conway, 2001). Malcolm et al.

(2003) argue that formal and informal learning

should not be viewed as separate forms at all, but

rather that all learning involves attributes of

formality and informality. This means that in

designing successful support, it is crucial to consider

characteristics of formality as well as informality.

Designing only for formality may disrupt the

informality (Brown and Duguid, 1998) that requires

a different kind of approach (Gutwin et al., 2008).

Svensson et al. (2004) also emphasise the need

to integrate formal and informal learning in order to

support learning in an organisation. Billett (2001)

argues that it is important to provide inviting

opportunities for engaged participation in order to

facilitate learning, and that it is vital to know the

prerequisites for participation in an organisation.

The intention with the model presented in this paper

is to explore preconditions contributing to such

learning.

To construct the model, focus was placed on

actual social interaction rather than on artificial

design of interaction, emphasising the informal, but

acknowledging the formal. Wenger, 1998, and Lave

and Wenger, 1991, see learning as inherently social

and propose Communities of Practice (CoP) as an

approach to view learning in organisations. The

concept of CoP is based on participants creating

informal relationships where they engage in social

interaction to achieve joint goals that sometimes are

aligned to organisational goals. Reviewing this

concept was therefore deemed as a suitable starting

point for creating a model that focuses on

relationships as fundamental for learning.

The review focused on core ideas of CoPs, and

on ideas presented in a literature review on CoPs by

Murillo (2010). Articles were collected in order to

establish the basic ideas of CoP and main criticisms.

During analysis, main ideas from the review were

formed into key phrases. These keys were then

analysed by searching for and finding keywords to

form patterns influencing on the emergence, growth

and existence of informal relationships. These

patterns were then formulated into main

preconditions influencing these relationships. These

preconditions were then used to create the

Precondition Profile model.

The paper continues with a section describing

the main preconditions concluded to be valuable for

the suggested model, ending with an illustration of

the model and its constituent parts. Then follow

some concluding remarks.

2 CONSTRUCTING THE MODEL

In the following, the preconditions contributing to

the construction of the Precondition Profile Model

are described as conclusions drawn from the review.

This description ends with presenting the model

including an illustration.

2.1 Participants

A core element of CoP as a social learning theory is

identity. As a person learns s/he (re)forms her/his

own identity (Campbell et al., 2009). Campbell et al.

(2009) suggest that an identity is never entirely

reformed, but that it is formed as overlapping and

composite experiences are made. Experiences are

made through learning and vice versa and thus

learning is closely connected to how people define

themselves based on perceived behaviour.

Behaviour is based on assumptions on what is

considered to be the appropriate way to behave

(Schein, 2003).

Wenger (1998) argues that learning changes who

people are and this means that there is a link

between learning and identity. For example, strong

or weak participants influence the learning in the

practice they belong to through their identities. They

may be strong due to the value that other participants

give them. This value forms their identity and the

perceived identity in the practice. Their interaction

then impacts differently on learning depending on

strength/weakness. Other characteristics of

participants’ identities also influence how the

relationships emerge and continue, for example traits

such as being open or resistant to various kinds of

influences in the form of for example attempts from

participants or leadership to change routines,

information flows or collaboration patterns. The

identity in the practice is influenced by how

participants form their identities as “being” a

specific competence of work, but it is also based on

LearninginanOrganisation-ExploringtheNatureofRelationships

497

personal characteristics. Lave and Wenger (1991)

view identities as “long-term, living relations

between persons and their place and participation in

communities of practice” (p. 53).

The conclusion is that the traits of participants

play a major role in how interactions in relationships

are carried out; that is, the nature of relationships.

Participants may be territorial, bureaucratic,

pragmatic, attentive, negligent, secretive, open-

minded etc. Pragmatic behaviour could result in for

example informal decision-making whereas

bureaucratic behaviour could result in directives

regulating every detail. Further, strong participants

may foster or hamper for example the degree of

liveliness and openness in relationships depending

on personal traits.

2.2 Authority, Status and Attitude

The concept of CoP has been criticised because it

may defer from considering issues of conflict and

power (Murillo, 2010). These issues could gain from

more attention, although Wenger (1998) discusses

marginalisation, positioning and initiatives arising

from personal agendas. A CoP can on the one hand

be creative, open and dedicated to cooperation, and

on the other a CoP can be conservative, introvert and

a venue for all kinds of positioning, abuse of power

and marginalisation (Wenger et al., 2002). Wielding

power by taking or withholding action influences

relationships by for example causing conflict or

consensus. Conflict could be a sign of strong

engagement whereas consensus could be a sign of

passivity or conforming to power. “Disagreement,

challenges, and competition can all be forms of

participation. As a form of participation, rebellion

often reveals a greater commitment than does

passive conformity” (Wenger, 1998, p. 77). Conflict

may also be the result of unresolved issues, and

consensus the result of hard work.

Within a community status and power may be

linked to competence, but the farther away a

community is from the centre of the organisational

power, the lesser the legitimacy acknowledged to the

community and its members (Yanow, 2004). Thus

power and status may be high within a CoP although

the CoP does not have legitimacy with leadership.

Yanow (2004) discusses marginalisation of an entire

CoP. Wenger (1998) however, addresses

marginalisation of members within a CoP that

occurs when contributions of members are ignored –

which may result in a feeling of non-belonging, and

when certain experience is not considered

competence (Wenger, 1998). The joint engagement

in relationships of a setting reflects the status of how

legitimised its work is. For example, engagement

may be devoted to open and elaborate activities if

work is highly esteemed and delivering results is

required.

There are many ways power may be wielded and

expressed. Tasks may for example be delegated

without being accompanied by empowerment to

conduct them. An example given by Yanow (2004)

shows how an organisation, despite having decided

that design should be developed from local needs,

continued to design without consulting the locally

competent employees. Yanow further describes that

employees were annoyed when leadership called

upon external consultants rather than calling upon

the competence of the employees. Another way to

wield power is to discourage communication.

Woerkum (2002) suggests that communication may

be discouraged by making it difficult to interact by

for example letting experts draft and present while

referring heavily on official documents, and by

letting the experts present in a vocabulary unfamiliar

and odd to the audience.

The above examples illustrate how power may

be exercised for different purposes. Power is likely

to influence relationships and thus learning. People

may form attitudes resisting change perceived as

forced upon them. Loyalty may be strengthened

locally in a practice as the participants close ranks

toward exterior pressure. An excessive use of power

may also be a sign of lacking trust between

leadership and employees. Lacking trust may result

in information staying local as it may be perceived

as risky to share it. A perceived need to secure

confidentiality may lead to self-censorship, which in

turn may be resolved by people by sending e-mails

to specific individuals, making phone calls and

linking to personal homepages (Ardichvili et al.,

2003). This kind of interaction to avoid control may

contribute to informality in relationships.

Much attention, feedback and support from the

leadership could be signs of what kind of status a

setting and its relationships hold. The engagement

and activity of senior managers is a crucial asset to a

CoP, and managers assuming the roles as champions

are needed (Wenger et al., 2002). Settings may

however be highly valued by leadership but not by

employees, and vice versa. Feedback and support

build on trust in relationships between colleagues

and between employees and leadership, and so do

confidence and commitment (Eraut, 2004). Without

feedback people do not know and are left to

speculate (Cramton, 2001).

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

498

Usually, management is about emphasising

motivation, productivity and rewards, while focus

alternatively could be on supporting learning by

allocating and organising work, and creating a

culture promoting informal learning (Eraut, 2004).

How leadership acts, or is perceived as to act, is thus

essential for how informality in relationships is

employed, and whether informality is aligned to

organisational goals.

The conclusion is that status and authority

influence relationships. For example, participants

may have strong informal as well as formal positions

in relationships. Through this power they may keep

interaction in relationships within a local setting

hidden or open to the rest of the organisation. All

participants hold attitudes as responses to exercised

power, status and trust. These attitudes influence

relationships as well. A high degree of seclusion

could relate to low status of the work being done in

the specific setting as there may seem to be no

reason to be open about something that there is little

interest in. Conflict or cooperation between

individuals may colour relationships and possibly

the organisation.

2.3 Resources

It is in the informal networks and not through policy

texts, that new ideas will be approved or

disapproved (Woerkum, 2002). However, it may be

problematic for ideas to emerge as people face

problems in learning from each other, for example

by not being able to access information due to lack

of resources for sharing this information. Tools as

well as a shared repertoire may be lacking.

According to Wenger et al. (2002) there are some

possibly helpful tools for members of a CoP, such as

an online space for conversation and discussions, a

repository to store documents, a search engine and a

directory with information on members. Digital

habitats are enabled by technology providing a place

for interacting (Wenger et al., 2009) and these tools

are some examples of such technology.

However, although resources to interact are

available, they may be little used which may weaken

participation and stifle relationships. According to

Ardichvili et al. (2003), people may fear losing in

trustworthiness and respect if contributing

something that is not entirely correct or adequate.

They argue further that people may fear being

critiqued or ridiculed, and that there is also an

uncertainty regarding expectations and

appropriateness of contributions. One possible

obstacle is that people may not know how to express

and describe what they know in a form suitable for

storage in a database (Verburg and Andriessen,

2011). Eraut (2004) reasons that an individual, who

perceives that s/he know things that no longer are

perceived as valid, may feel a loss of control over

the own participation in a practice. That individual

turns into a novice again at the same time as s/he is

not considered by others to be a novice.

Issues of power, status and trust may also be

seen as resources for relationships in the way they

influence participants. Leaders that participate in

informal relationships may be seen as a resource that

influences positively or negatively. The informal

role of a manager has considerable impact on

learning at work and is expressed as the personality,

interpersonal skills and learning orientation of the

manager (Eraut, 2004). Another crucial resource is

time allotted, which could be expressed in terms of

personnel allocated. If time is scarce, a participant in

one setting may prioritise other matters in line with

what the organisation appreciates. Conversely, a

participant may continue to act in relationships

within a setting of own prioritisations despite what

the organisation favours.

The conclusion is that resources influence how

relationships are shaped and carried out. A setting

may be enabled, and thus its relationships, by

resources. It could also be disabled by inappropriate

or insufficient resources.

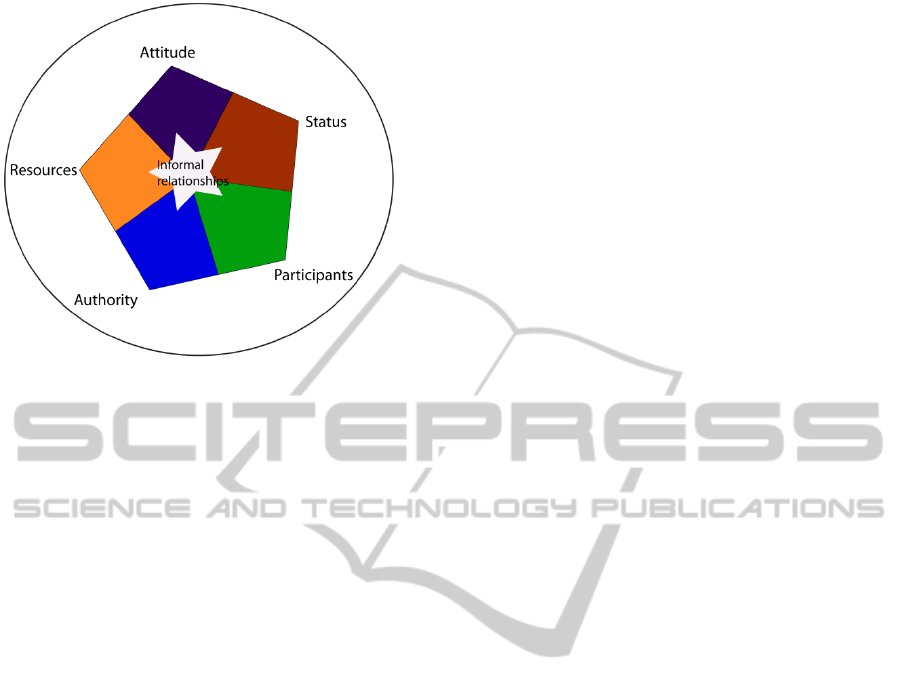

2.4 The Precondition Profile Model

The core issues presented in the previous section

resulted in the model depicted in Figure 1, the

Precondition Profile Model. The model shows some

main preconditions for informal relationships to

emerge, grow and exist through interaction. The

issues are represented in five preconditions:

1) Attitude – how open interaction is to new

influences and to sharing within a setting

and outwards.

2) Status – how legitimised interaction is and

by whom.

3) Participants – how likely interacting

participants are characterised viewed in

terms like personal traits, activity and

engagement.

4) Authority – how power and trust influence

interaction.

5) Resources – how availability and

characteristics of resources influence

interaction.

LearninginanOrganisation-ExploringtheNatureofRelationships

499

Figure 1: A Precondition Profile Model to show

preconditions for informal relationships.

Together, the preconditions in Figure 1 form a

“precondition profile” that supplies an organisation

with a profile depicting predominantly informality

aspects in the nature of relationships. The five parts

representing the preconditions in the model

influence each other and therefore they need to be

considered together. Then, when implications for

learning in the current nature of relationships have

been analysed, it may be possible to manipulate

variables of the preconditions.

The preconditions of the model have been

applied when studying learning in the Swedish

Armed Forces (SwAF) (Dessne, 2013). Each

precondition proved useful for understanding the

nature of relationships in the SwAF. As each

precondition may consist of various factors it was

possible to see how a factor for example enabled or

disabled learning in the studied setting.

3 CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Precondition Profile Model focuses on the

aspect of informality in the nature of relationships.

As informal relationships emerge within designed

relationships, the formality aspect is applicable as

well. Human relationships always contain aspects of

informality, more or less obvious. Focusing on

informality but acknowledging formality contributes

to an approach of combination rather than

separation, as suggested by Rasmussen and Nielsen

(2011), Svensson et al. (2004) and Malcolm et al.

(2003). Compared to for example CoPs the

Precondition Profile Model also offers a way to

approach all informal relationships in an

organisation, not just in the form of CoPs.

The Precondition Profile Model may be used as a

framework to understand preconditions for the

nature of relationships in a defined setting. A setting

may be defined by for example work tasks or

organisational objectives. The preconditions should

preferably be explored together as they influence

each other making features valid through various

perspectives.

Learning is, as stated in the beginning of this

paper, a consequence of social interaction and

interpretation and thus the nature of relationships

impacts on learning. Therefore it is necessary to be

aware of and understand this nature in order to be

able to manipulate it for learning purposes. To

facilitate preconditions could involve matters of

design, thereby interfering with formality on

informality. To impose formality on informality has

been claimed in research as recommendable (e.g.

McDermott and Archibald, 2010, Lesser and Storck,

2001, Wenger et al., 2002). Ardichvili et al. (2003)

suggest however that supporting and enriching

participation in practice and hence facilitating

learning is what matters, rather than attempting to

direct. Whatever measures are taken, they are likely

to change the preconditions both in intended and

unintended ways. Interfering with one precondition

may impede on another in an unpredicted way. It

may therefore be advisable to be careful and

moderate when manipulating the preconditions.

To facilitate learning is to provide preconditions

that enable participants to learn by being nourished

with information gained from each other. Providing

preconditions for a suitable and healthy nature of

relationships is a way to nourish and encourage

learning. Such a suitable and healthy nature ought to

provide desired information accessed by

participating in relationships. The constructed model

may be a point of departure for this facilitation of

learning, both for organisations and for continued

research. The model depicts how participants,

authority, attitudes, status, and resources are

connected through for example the way participants

form attitudes toward sharing information. They

engage in relationships influenced by themselves

and issues of status, authority and resources. Their

relationships emerge informally, influenced by for

example a leadership that exercises power in both

formal and informal ways. The availability,

characteristics and use of resources influence and

contribute to informal as well as formal interaction.

The need for an integrated approach to learning in an

organisation is based on this kind of intertwined

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

500

features and connections. The Precondition Profile

Model aims to contribute to such an approach.

REFERENCES

Ardichvili, A., Page, V. & Wentling, T. 2003. Motivation

and barriers to participation in virtual knowledge-

sharing communities of practice. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 7, 64-77.

Billett, S. 2001. Learning through work: workplace

affordances and individual engagement. Journal of

Workplace Learning, 13, 209-214.

Brown, J. S. & Duguid, P. 1991. Organizational learning

and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view

of working, learning, and innovation. Organization

Science, 2, 40-57.

Brown, J. S. & Duguid, P. 1998. Organizing Knowledge.

California Management Review, 40, 90-111.

Burns, T. & Stalker, G. M. 1961. The Management of

Innovation, London, Tavistock Publications.

Campbell, M., Verenikina, I. & Herrington, A. 2009.

Intersection of trajectories: a newcomer in a

community of practice. Journal of Workplace

Learning, 21, 647-657.

Conway, S. 2001. Employing Social Network Mapping to

Reveal Tensions Between Informal and Formal

Organisation. In: Jones, O., Conway, S. & Stewart, F.

(eds.) Social Interaction and Organisational Change:

Aston Perspectives on Innovation Networks. London:

Imperial College Press.

Cramton, C. D. 2001. The Mutual Knowledge Problem

and Its Consequences for Dispersed Collaboration.

Organization Science, 12, 346-371.

Dessne, K. 2013. Formality and Informality: Learning in

Relationships in an Organisation (Manuscript

submitted for publication).

Diefenbach, T. & Sillince, J. A. A. 2011. Formal and

Informal Hierarchy in Different Types of

Organization. Organization Studies, 32, 1515-1537.

Eraut, M. 2004. Informal Learning in the workplace.

Studies in Continuing Education, 26, 247-273.

Gutwin, C., Greenberg, S., Blum, R., Dyck, J., Tee, K. &

McEwan, G. 2008. Supporting Informal Collaboration

in Shared-Workspace Groupware. Journal of

Universal Computer Science, 14, 1411-1434.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. 1991. Situated Learning:

Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press.

Lesser, E. & Storck, J. 2001. Communities of practice and

organizational performance. IBM System Journal, 40,

831-841.

Malcolm, J., Hodkinson, P. & Colley, H. 2003. The

interrelationships between informal and formal

learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 15, 313-318.

Marsick, V. & Watkins, K. E. 2001. Informal and

Incidental Learning. New Directions for Adult and

Continuing Education, 25-34.

McDermott, R. & Archibald, D. 2010. Harnessing Your

Staff’s Informal Networks. Harvard Business Review,

1-7.

Meyer, J. W. & Rowan, B. 1977. Institutionalized

Organisations: Formal Structure as Myth and

Ceremony. The American Journal of Sociology, 83,

340-363.

Murillo, E. 2010. Communities of Practice in the business

and organization studies literature. Forthcoming in

Information Research, 1-48.

Ran, B. & Golden, T. J. 2011. Who Are We? The Social

Construction of Organizational Identity Through

Sense-Exchanging. Administration & Society, 43, 417-

445.

Rasmussen, P. & Nielsen, P. 2011. Knowledge

management in the firm: concepts and issues.

International Journal of Manpower, 32, 479-493.

Schein, E. H. 2003. On Dialogue, Culture, and

Organizational Learning. Reflections reprinted from

Organizational Dynamics, vol. 22, 1993, 4, 27-38.

Svensson, L., Ellström, P.-E. & Åberg, C. 2004.

Integrating formal and informal learning at work. The

Journal of Workplace Learning, 16, 479-491.

Wang, C. L. & Ahmed, P. K. 2002. The Informal

Structure: hidden energies within the organisation.

University of Wolverhampton Working Paper Series

2002, 13.

Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning,

Meaning, and Identity, Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. & Snyder, W. M. 2002. A

guide to managing knowledge: Cultivating

Communities of Practice, Boston, Harvard Business

School Press.

Wenger, E., White, N. & Smith, J. D. 2009. Digital

Habitats: stewarding technology for communities,

Portland, CPsquare.

Verburg, R. M. & Andriessen, E. J. H. 2011. A Typology

of Knowledge Sharing Networks in Practice.

Knowledge and Process Management, 18, 34-44.

Woerkum, C. v. 2002. Orality in environmental planning.

European Environment, 12, 160-172.

Yanow, D. 2004. Translating Local Knowledge at

Organizational Peripheries. British Journal of

Management, 15, S9-S25.

LearninginanOrganisation-ExploringtheNatureofRelationships

501