Customised eTextbooks

A Stakeholder Perspective

Clemens Bechter and Yves-Gorat Stommel

Thammasat Business School, Thammasat University, Tha Prachan, Bangkok, Thailand

Keywords: eBooks, Electronic Textbooks, Self-publication, Customisation, Personalisation.

Abstract: In this article we present a reader’s as well as an author’s perception of customized eTextbooks.

Customisation providers such as editors, translators and graphic designers were asked about their preferred

model of compensation for their work by self-publishing eTextbook authors or publishers. Although the

royalty model was preferred by authors, most providers prefer an upfront payment. The main goal of this

paper is to assess the value that stakeholders put on customised content. A survey conducted in 2013

showed that readers are not willing to pay a substantial amount for customisation. Readers associate a high

level of risk with purchasing a self-published eTextbook. Respondents considered a fair retail price for self-

published eTextbooks should be a third lower than those distributed by publishing houses. However, current

prices charged by renowned publishing houses for a typical post-graduate level textbook chapter (i.e.,

around US$ 8-9) are higher than readers (e.g., students) consider reasonable. Convenience is the major

factor determining why people read eTextbooks and recommendations by peers and forum members rank

top in creating awareness and influencing the actual purchase. The authors recommend a system based on

collaborative filtering to provide customization options to readers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Customisation has spread to increasingly diverse

areas such as creating one’s own holiday by mixing

and matching transportation, accommodations,

restaurants and experiences, so no holiday needs to

be the same. Other examples are: t-shirts (graphical

design), M&Ms (text messages on sweets), own

blend of tea or coffee, eyeglasses, golf clubs to name

a few. One of the latest examples is the book market.

The global book market was valued in excess of

US$120 billion in 2011 (Lucintel, 2012). Digital

versions of books ‘eBooks’ are taking away market

share from printed books, while reinventing the

medium itself due to lower cost, easy distribution

and digital functionalities. Fuelled by cheap

distribution and low production cost, there is a

continuously growing market of self-published

eBooks. A sub-type of eBook is the eTextbook,

mainly read by students and compiled by tutors

(instructors). Whereas the printed hardcover

textbook of a post-graduate course can amount to

US$200 or more, the electronic version is offered, at

best, for half that price. Most leading academic

publishing houses offer customisation options.

Instead of selling a complete textbook (e.g., 800

pages, 22 chapters), they offer chapters for around

US$8.50 each. Tutors can pick the content they like

and may add third party case studies, simulations or

whatever they consider suitable. However, the more

copyrighted materials the more expensive the

customised eTextbook becomes.

Tutors are becoming more and more interested in

customising their textbooks. Large academic

publishing houses support this trend by offering

customisation sites for their textbooks and provide

instant gratification by offering instantaneous

delivery of the compiled eTextbook. Besides large

publishing houses there are intermediaries that

negotiate license fees with various content providers

on behalf of the self-publisher or buyer. Buyer could

be a professor teaching a course or a whole

university that wants to customise textbooks for their

courses.

Self-publishers often rely on third party service

providers such as graphic designers and animation

developers. The starting point can be a text, to which

other providers can add covers, layouts, edited

versions, translations, etc. The eTextbook project

initiator can decide to either own the content/design

163

Bechter C. and Stommel Y..

Customised eTextbooks - A Stakeholder Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0004765301630170

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 163-170

ISBN: 978-989-758-022-2

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

by paying a fixed amount to providers, or to work

with other content providers on a royalty basis

(Stommel and Bechter, 2013).

According to Goldberg (2011), self-published

books outnumber traditionally published ones by 2

to 1, with more than 210,000 titles being self-

published (based on ISBN statistics) each year. The

growth rate of eBook self-publishing is a factor of

four higher than printed book self-publishing (Rice,

2012). Self-publishing activities are estimated to

have led to traditional publishing houses missing out

on some US$100 million in revenue in 2011 (Rice,

2012). Self-publishing of eBooks is fuelled through

an increasingly large number of service providers,

with an increasingly diverse focus. The more the

market matures, the more service providers have to

specialise.

While the vanity aspect of being published

instead of self-published is still a factor for some

authors (Jia, 2012), this seems to become less of an

issue for academic authors. Hence, according to

some researchers, self-publishing will become the

norm for eTextbooks (Goldberg, 2011).

Some authors recommend that tutors give away

their self-published eTextbooks for free because

royalties earned are only of secondary consideration

for academics (Hilton and Wiley, 2010). For

example, eTextbooks are already available at the

Worldreader digital library, where African children

have free access to such educational eBooks on their

mobile phone or donated Kindles, initiated by David

Risher, a former Amazon executive (Wingfield,

2012; Fowler and Bariyo, 2012).

Besides the obvious advantages of working with

eTextbooks, self-published or not, there are

disadvantages:

Lack of universal publishing standards.

Sharing/lending books becomes difficult without

violating copyrights (Fister, 2010).

Privacy might be impacted when personal text

markings (shared on some reading platforms) are

utilised by others (Fister, 2010).

No bookshop support (Fister, 2010).

No chance of becoming a collector’s item (Jia,

2012).

Issues pertaining to Digital Rights Management

(Fister, 2010).

Loss of income to authors because of piracy

(Williams, 2012).

Usually, publishers grant licenses for a limited

period of time (e.g., three years) and demand high

sales (e.g., 200+) volumes. Especially students may

complain that a used, customised eTextbook cannot

be sold on to junior batches because of the

customised content.

While a significant share of available eTextbooks

are direct copies of print to the digital environment,

partly in order to mimic the reading experience of a

print book (layout, switching pages, etc.), some

additional functions have already been incorporated

(Alfa Bravo, 2011):

Adding/sharing/seeing other student’s notes

eTextbook recommendation by email, Facebook,

Twitter, etc.

Online rating

Text highlighting/copying

Adding bookmarks

Choice of fonts, font sizes and background

colours

Text search

Usage on multiple devices

Integration of animations, simulations and digital

stories

Integration of audio files (audiobook)

eTextbooks increasingly exploit the digital

nature and include audio and video content, as well

as hyperlinks and other interactive aspects.

Examples are learning about chemistry (Swanson,

2011) and medical education (Husain, 2011)

respectively. However, in most cases, these

additional functionalities are often not yet

compatible with eReaders, and can only be accessed

on tablet computers.

Customisation is often supported by

‘granulation’ of creative efforts (Stumberger, 2012).

A book project is split into very small components.

Long term work contracts often make way for

assignments, with individuals contributing their

expertise for a very short period of time to such

eBook projects involving a large number of

individuals (Stumberger, 2012). From the author’s

point of view, benefits can be derived from a

virtually unlimited source of providers, potentially

located world-wide, with high speed interaction

(Velamuri, 2012). On the downside, typical concerns

are intellectual property theft and the missed chance

of building competencies within the publishing

house or the self-publisher her/himself.

It is difficult to get reliable data on the market

share of self-published eBooks. Estimates for the

U.S. market range from 30% market share of self-

published eBooks to 77 % (McLaughlin, 2012). The

revenue share of self-published eBooks is generally

lower compared to the volume share, because self-

published eBooks are lower priced than published

ones.

The strong growth in eBook consumption has

been propelled by widely available eReaders (e.g.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

164

Kindle), tablet computers and smart phones, which –

at the end of 2011 – enabled 807 million consumers

around the world to read eBooks on their devices

(Research and Markets, 2011). By 2015 this number

is expected to grow to 1.8 billion unique users

worldwide – this reach is roughly equal to the

expected reach for daily newspapers (Research and

Markets, 2011).

The most popular eBook formats are epub,

kindle and pdf. By offering an eBook in all three

formats, basically every available reader can process

a copy of an eTextbook.

2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Since the eTextbook market is very young and

dynamic, most recent information can only be found

on the web. This leads to an overrepresentation of

online sources compared to academic journals,

which in some cases might result in

overemphasising the point of view of individuals.

For example, forum discussions are a good indicator

of the latest developments in this very young

industry, however, they often represent the

convictions of single individuals only. The purpose

of this study was to analyse the process of how

eTextbook readers find / choose their next book and

whether they had an interest in customisation and

self-published books.

Apart from readers, the criteria of authors for

selecting their self-publishing provider and the

interest in customisation by outsourcing parts of the

project were also analysed. Besides readers and

author the third target group of the research were

graphical designers, editors and translators. It has

never been analysed whether such providers are

willing to offer their services to a self-published

eTextbook on a royalty basis and if for how much.

The research questions were:

How does the eTextbook reading community

perceive self-published eBooks versus the ones

by renowned publishing houses?

Does this community have an interest in

customising their eTextbook?

What is the community willing to pay for

eTextbook customisation?

How and on what motivational basis do self-

publishing authors find and choose their self-

publishing provider?

What are the main perceived advantages and

disadvantages of self-publishing eTextbooks for

authors?

Which aspects of eTextbooks – apart from the

text – are the most crucial to the success

according to authors and readers? What would be

its monetary value?

Are providers such as freelance graphical

designers, translators and editors willing to work

for self-publishing authors for royalties on sales?

How high would those royalties need to be?

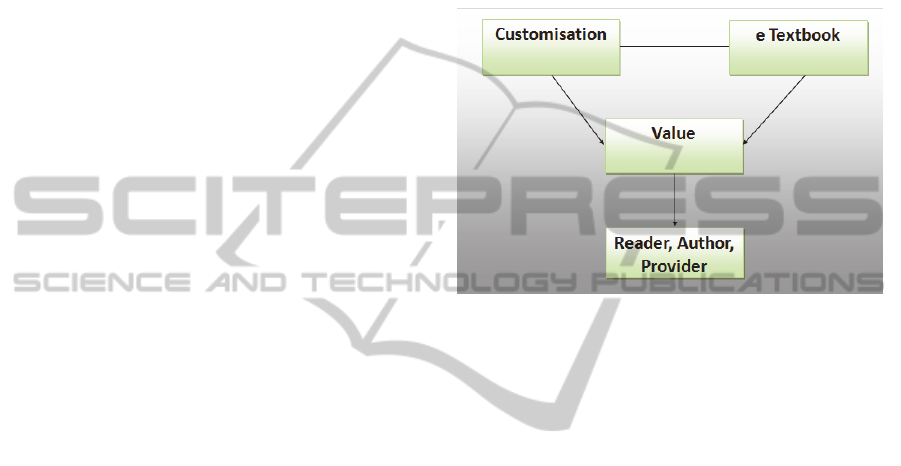

Figure 1: Research Framework.

The questionnaire addressing the value

perception of Readers included 23 questions

subdivided into 5 main categories:

1. Consumer reading habits and motivation: Time

spent reading eBooks, type of eBooks, type of

eReader and motivation for reading. From the

various available motivational theories (Kotler et

al., 2013), Maslow’s theory was chosen as it is

relatively straight-forward and lends itself better

to online questionnaires (reducing the number of

questions) compared to for example Hertzberg’s

theory (distinguishing between satisfiers and

dissatisfiers).

2. Consumer psychology: The perception of self-

published vs. published eTextbooks. Other

stimuli for reading eBooks.

3. Marketing stimuli, buying decision process and

purchase decision in regards to becoming aware

of, finding and choosing eTextbooks.

4. Interest in customising written content and

willingness to pay a premium for it.

5. Consumer characteristics: social, personal

(demographic) and cultural parameters of the

reader.

The questionnaire addressing Author issues

included 25 questions subdivided in 6 main

categories:

1. Introduction and author publishing history: the

number of eBooks and the formats published in.

CustomisedeTextbooks-AStakeholderPerspective

165

2. The publication motivation.

3. Publishing provider: How was the provider

found and chosen, what are the business model

preferences, what did the author learn from the

collaboration?

4. Opinion/usage/pricing of (self-published)

eTextbooks: analysis of author’s perception on

self-publishing and pricing.

5. Author’s interest in add-ons to the written

content and willingness to pay royalties.

6. Social, personal (demographic) and cultural

parameters.

The third group, the Providers, were asked one

question only concerning their willingness to

provide building blocks to a self-published

eTextbook without upfront payment, while

participating in revenue sharing through royalties

and stating her/his expected share of the cake.

Because the largest social networks are not

professional ones (e.g. Facebook, Myspace,

Google+), these were deliberately not used as data

source. Some of the reasons for this decision were:

Too big a network can quickly lead to

participants of lower relevant qualification and

lower quality exchanges (Postrel, 2007).

Niche social networks are often better suited to

effectively reach the target market segments

(Kotler et al., 2013).

Therefore, the author/provider questionnaires

were posted in following groups, see Table 1.

Table 1: Questionnaire postings: authors and providers.

Network Group Members Survey

Xing eBook ~400 Authors

Xing

Überse

t

~5,000 Editors/Transl.

LinkedIn

LinkEd

~49,000 Editors

LinkedIn

ProZ.c

~28,000 Translators

LinkedIn

Freelan

~4,000 Transl./Designer

Readers were approached through twelve online

eBook forums.

All in all 616 responses were received out of

which 400 were readers, the rest was made up of

authors, editors, graphic designers, and translators.

The predominant age group was 41 to 50 years of

age. 41% came from the USA, followed by UK and

Germany.

3 FINDINGS

Findings are based on surveys of readers, authors,

and providers such as translators, editors and graphic

designers.

3.1 Readers

Most readers used a Kindle (54 %), Sony eReader

(17 %), Kobo (7 %) or Apple portable device (7 %).

The primary reason/motivation for reading

eTextbooks is convenience,see Table 2.

Table 2: Motivation eTextbook purchase.

Scale: 1 (low) – 10 (high) Mean StDev

Convenience 8.8 1.62

Ease of storage 8.6 1.97

Size of library 7.8 2.18

Interactive components 3.2 2.51

Video/audio content 2.2 1.95

Adjustable font (size) 7.7 2.19

Gender differences for the parameters listed in

Table 2 were evaluated through mean differences. A

t-test indicated significant differences for

‘Convenience’, ‘Ease of storage’ and ‘Adjustable

font size’, which were significantly higher ranked by

women. When comparing the expected price

difference for published vs. self-published eBooks,

all respondents expect the same or a lower price for

the self-published eTextbook, with the median at 45

% i.e. 45% price deduction for a self-published

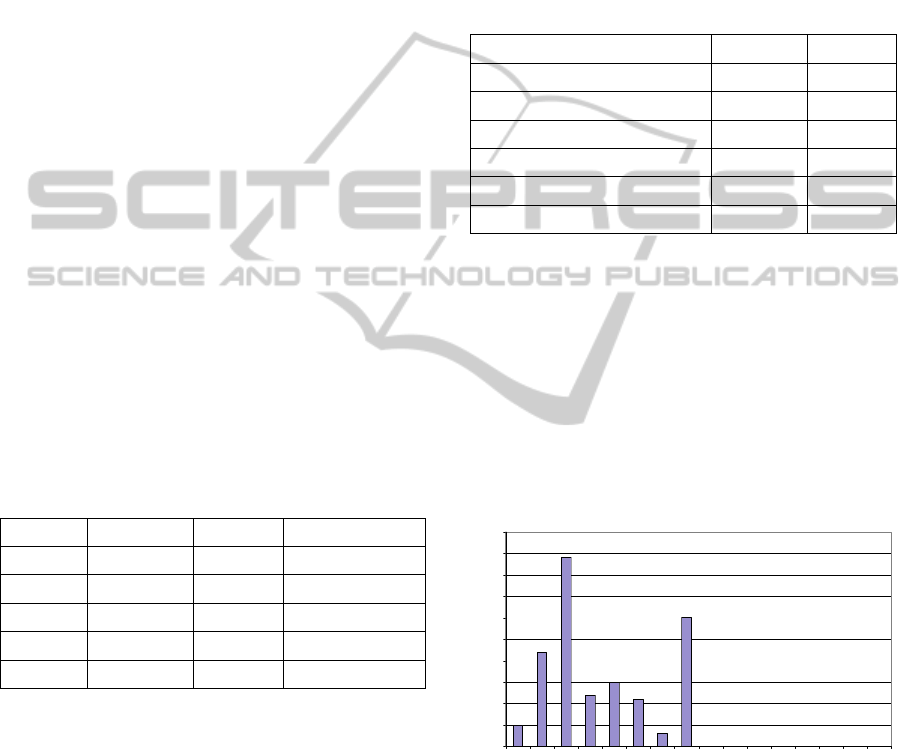

book, see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Price perceptions.

The main reason for the expected discount is the

perceived risk of poor quality when buying a self-

published eTextbook. To check for interdependence

between the discount and other reasons than risk for

the expected discount (e.g. lower production cost,

lower overhead, less marketing expenses), a cross

tabulation was carried out, followed by a calculation

of Lambda coefficient and Goodman and Kruskal

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

-90 -70 -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 +10 +20 +30 +40 +50 +70 +90 +100

Premium (+) or discount (-) for a self-publ. versus a publ. eBook [%]

Count [-]

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

166

tau in order to test the strength of the associations.

Both statistics showed no association between

expected discount and other justifications.

The next questions were: how do readers become

aware of these self-published eTextbooks and what

additional electronic features do they expect and

how much more are they willing to pay?

Table 3: Awareness sources.

Mean

Stand.

Dev.

Online ad 3.9 2.65

Information in article 5.3 2.42

Online posting by author 4.1 2.74

Recommendations from friends /

in forums

7.9 2.23

Book seller recommendations

based on prior readings

5.4 2.76

Book seller homepage

recommendations

4.3 2.61

Browsing by topic on book seller

homepage

5.5 2.81

Browsing by price on book seller

homepage

3.9 2.72

Recommendations by friends and forums were

the most important factor when becoming aware of a

new eTextbook, see Table 3, as well as actually

purchasing it, see Table 4.

Table 4: Buying criteria.

Mean Stand. Dev.

Forum/friend recommendations 8.0 2.10

Book seller recommendations 5.1 2.55

Readers' reviews 6.8 2.17

Cover 4.9 2.51

Price 6.3 2.60

Sales rank 3.6 2.60

Blurb/book summary 7.3 2.19

Reading sample 6.8 2.97

Blurb and a reading sample ranked second and

third.

Readers were given seven customisation options

which they had to rank between 1 (lowest interest)

and 5 (highest), see Table 4.

Average interest in any of the given

customisation options was low, with the choice of

book cover ranking highest. As a direct result, the

premium that the respondents are willing to pay for

customisation options is relatively low ranging from

US$0.06 to maximum US$0.13 (adding personalised

content). Respondents who were interested in a

choice of book cover, were as well interested in a

choice of graphics and choice of layout versions, see

Table 6.

Table 5: Customisable features.

Mean

Stand.

Dev.

Animations 1.5 1.51

Choice of book cover (based on

content)

2.8 2.58

Choice of graphics intermixed with

text

2.5 2.33

Choice of edited versions

(short/long)

2.3 2.13

Choice of layout versions (e.g.

gothic, fairytale, modern, …)

2.5 2.24

Adding of digital stories 2.1 2.10

Adding of personalised content 2.4 2.36

Table 6: Customisation Options Correlations.

Cover Graphics Layout Age

Cover

Pearson

Corr.

.607

**

.536

**

-.209

*

N 140 140 140 138

Graphics

Pearson

Corr.

.607

**

.483

**

.195

*

N 140 140 140 138

Layout

Pearson

Corr.

.536

**

.483

**

.194

*

N 140 140 140 138

Age

Pearson

Corr.

-.209

*

.195

*

.194

*

N 138 138 138 138

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

No association between customisation options

and gender was found. In order to reduce the number

of answers/variables, a factor analysis of the

questions with numerical scale was conducted. Table

7 shows that ten variables can be condensed into

four factors (also known as components or

dimensions). Factor one can explain the most (22%)

and factor 4 the least (12%) of variance.

The four factors can be described as follows:

1. The first factor has four high loading variables

(cut-off : 0.6) and can be described as valuing the

‘easy to use’ characteristics of eTextbooks.

2. The second factor has two high loading variables

and can be described as valuing the ‘interactive’

characteristics of eTextbooks.

3. The third factor has two high loading variables.

CustomisedeTextbooks-AStakeholderPerspective

167

The dimension can be described as ‘sales price’

dimension.

4. The fourth factor reflects the ‘discount’ that a

self-published eTextbook comes with.

Convenience in the broadest sense is the main

reason. Second reason reflects the additional

interactive features that eBooks offer.

Table 7: Major Factors.

Factor Loadings

1

(22%)

2

(16%)

3

(15%)

4

(12%)

Ease of storage 0.779 0 -0.10 0.014

Size of

library/modules/chapters

0.730 0.017 -0.21 0.172

Convenience 0.666 0.035 0.158 -0.2

Adjustable font 0.636 -0.06 0.148 -0.09

Reading time 0.478 -0.31 0.031 0.202

Interactive components 0.069 0.892 -0.01 0.001

Video/Audio content -0.14 0.852 0.148 0.126

Price published

eTextbook

0.057 0.009 0.896 -0.25

Price self-publ.

eTextbook

-0.03 0.17 0.806 0.464

Discount self-publ.

eTextbook

-0.01 0.069 -0.02 0.932

3.2 Authors

A total of 90 authors answered the questionnaire.

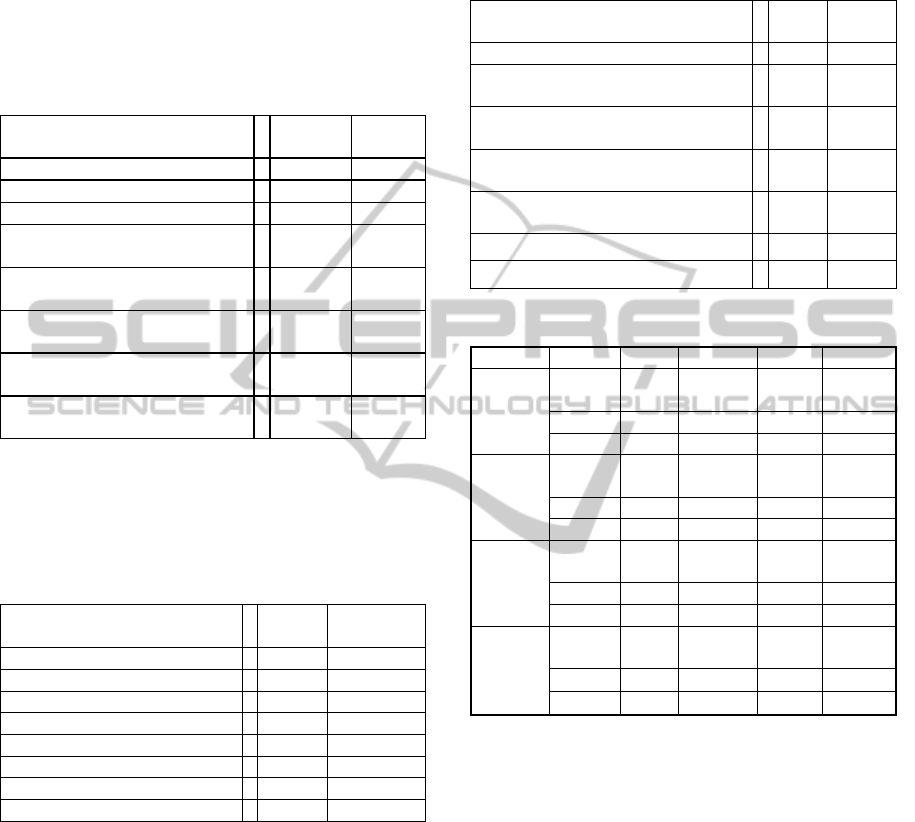

The predominant age group was 31 to 65, see Figure

3.

Figure 3: Age distribution authors.

When asked about their motivation, income

seems the main driving force to write eTextbooks,

see Table 8, but self-development in the sense of

Maslow’s motivation theory ranked a close second.

One can hypothesise that the more global

exposure of an eTextbook the more income can be

generated through royalties or revenue when self-

published. This was confirmed by our research

finding, see Table 9.

Table 8: Authors’ Motivation.

Mean Stand. Dev.

(additional) Income 7.3 2.73

Peer pressure 1.3 1.24

Self-esteem 5.1 3.28

Recognition by others 4.3 2.98

Status 3.4 2.46

Self-development 7.1 3.05

Table 9: Why author eTextbooks?.

Mean

Stand.

Dev.

eTextbooks are the future 8.0 2.23

eTextbooks are cheaper to produce 8.9 1.82

eTextbooks give global access

9.1 1.65

eTextbooks are interactive 5.2 3.30

eTextbooks come with video/audio

content

4.6 3.40

eTextbooks give a better chance of

success

8.5 2.29

When asked to assign a fair selling price to one

of their own eTextbook chapters, the average was

US$3 or 25% lower than the readers are willing to

pay. However, the authors think in terms of income

and the readers in terms of retail price (incl. VAT)

so both are not too far apart.

The preferred compensation model of working

together with service providers was on a royalty

basis (82%) versus upfront payment. When it came

to the question how authors chose their current

publisher, the distribution reach ranked highest. The

amounts they are willing to share are relatively

small, see Table 10.

Table 10: Authors’ Royalty Model.

in US$ Mean Stand. Dev.

Cover 0.25 0.22

Graphics 0.16 0.18

Editing 0.26 0.21

Layout 0.17 0.17

Translation 0.26 0.25

Digital Stories 0.21 0.32

On average translation ranked highest, a fact that

is down to non-English speaking authors. Assuming

that an eTextbook gets sold 10,000 times then

US$2,600 would go to the translator.

3.3 Providers

Nineteen graphical designers took part in the survey.

Only a third of respondents would consider

providing a cover based on a royalty model. The

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

<14 14-18 19-24 25-30 31-40 41-50 51-65 >65

Age group [years]

Count [-]

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

168

ones who did, consider around US$1 as a fair share

for their contribution to an eTextbook, a far cry from

the US$0.16 per book that authors consider as

appropriate. Out of the twenty five editors who

participated only 25% consider the royalty model as

fair. The few who would settle for it consider around

US$0.70 as fair share. 56 out of 82 translators were

not willing to contribute without upfront payment

and 8 would consider this on a case by case basis.

Royalty expectations are in the region of US$1.50

per eTextbook chapter.

In conclusion, providers ask for more than

authors and readers are willing to pay. However, it

has always been difficult to evaluate the willingness

to pay. Most people underestimate their propensity

to buy. In this context a conjoint analysis may yield

more reliable results and can be scope of further

research.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The eTextbook reading community finds its next

read through recommendations of friends and in

forums. Self-published books should be priced at a

45% discount. Generally, eTextbook readers are not

willing to pay a significant amount of money for any

type of customisation. Convenience is the main

factor why people buy eTextbooks. This may

explain why customisation is not considered a major

value-added feature. The moment a reader has to

think about customisation, the convenience suffers.

A compensation model based on royalties will work

for authors but not for service providers.

5 IMPLICATIONS

Focusing on instructors, publishers have to take the

initiative and offer customisation services.

Otherwise they risk that tutors/instructors offer their

textbooks in form of self-publishing and may even

give it away for free. The eTextbook customisation

itself can be done in-house or outsourced through a

straight buy or on royalty basis. Tough negotiations

between self-publishing authors on one side and

graphic designers, translators, editors on the other

side can be expected.

Asian students may want digital stories dealing

within an Asian context whereas Europeans may go

for their cultural setting. In a more formal approach

this can be done in two ways. The first technique is

content based filtering (Pazzani, 1999). This filtering

technique could, for example, suggest book covers,

layout formats etc. to readers based on a set of

eBooks in which readers have expressed interest or

bought in the past. Collaborative filtering (Konstan,

1997), the second method, is making automatic

predictions (filtering) about interests/preferences of

a reader by collecting information from many other

neighbouring readers.

Collaborative Filtering systems usually take two

steps: Firstly, look for readers who share the same

patterns with the user. Secondly, use the ratings

from those like-minded neighbours found in step 1

to calculate a customisation prediction for a specific

eTextbook reader/customisation and his/her

willingness to pay a certain amount for it.

n

u=1

(r

u,i,k

–

u

) * w

a,u

P

a,i,k

=

a +

_________________

n

u=1

w

a,u

P

a,i,k

: prediction for reader a for customisation

feature i under a given price k

n : number of neighbours u

w

a,u

: similarity weight between reader a and u

r

u,i,k

: rating neighbour u for customisation

feature i under a given price k

a

: average rating reader a

u

: average rating reader/neighbour u

The likelihood that a reader is willing to pay for

a certain customisation feature (e.g. a personalised

digital story) can be calculated according to above

formula. It depends on the reader’s general

disposition i.e. some readers want to have any

possible customisation, others are more cautious.

The prediction whether reader a likes customisation i

is based on his/her neighbours. The similarity index

w

a,u

is a simple correlation.

In the era of digitalisation, customisation can

easily be done as demonstrated. Surprisingly, no

publisher has seriously pushed it yet. Offering book

chapters and case studies as modules lacks the

potential that custom eTextbooks offer, even more

so when they come at a deterring price.

Another media industry that went through a

similar experience is the music industry. Nowadays,

most money is made by selling merchandise and

concert tickets and not by music recordings itself.

Some artists even post their songs for free on sites

CustomisedeTextbooks-AStakeholderPerspective

169

like Youtube and make money through advertising.

A real game changer could be the eTextbook

because it engages students and tutors. Although

lacking the traditional administrative backend of a

LMS, an eTextbook can offer a wider variety of

interactive features and choice of devices. Publishers

have been offering eTextbooks in the form of course

content integration but not as LMS in its own right.

Especially in the context of blended learning, where

a physical infrastructure and administration system

already exists, the drawback of a missing backend

can easily be overcome. Both, LMS providers and

publishing houses commit to ‘doing the things right’

by adding more and more technical features to the

LMS and publishing more and more textbooks in

prevailing eBook formats. The real mantra, however,

should be ‘doing the right things’ by delighting

customers – the students. Students love their mobile

phones that enable them to access all sorts of

information, from friends to lectures. This is a major

advantage of m-learning. Since publishing houses,

universities and LMS providers are not necessarily

known for delighting customers or embracing

disruptive innovations, it may be self-publishing

eTextbook authors who will the first to provide

engaging m-learning (Bechter and Stommel, 2014).

REFERENCES

Alfa Bravo, (2011). Where is the e in ebooks?,

alfabravo.com/2011/08/where-is-the-e-in-ebooks/,

accessed February 18, 2012.

Bechter, C., Stommel, Y. G. (2014), eTextbook – the real

student-centered LMS, China Education Review A &

B, 3(4), pp. 17-27.

Fister, B., (2010). Ebooks and the Retailization of

Research, Library Journal, August, pp. 24-25.

Fowler, G. A., N. Bariyo. (2012). An eReader Revolution

for Africa? The Wall Street Journal, http://

online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303768104

577462683090312766.html, accessed 2. August 2013.

Goldberg, T. J., (2011). 200 Million Americans Want to

Publish Books, But Can They?,

publishingperspectives.com/2011/05/200-million-

americans-want-to-publish-books/, accessed August

21, 2013.

Hilton, J., D. Wiley. (2010). A Sustainable Future for

Open Textbooks? The Flat World Knowledge Story.

First Monday, 15(8).

Hilton, J., D. Wiley. (2011). Free e-Books and Print Sales.

The Journal of Electronic Publishing, 14(1).

Husain, I., (2011). Interactive iPad Medical Textbooks

gain traction, www.imedicalapps.com /2011/03/ipad-

medical-textbooks-e-books-mobile-medical-text/,

accessed February 21, 2012.

Jia M., (2012). Paper vs Pixels, China Daily, March 18,

pp.1-3.

Konstan, J. A., B. N. Miller, D. Maltz, J. L. Herlocker, L.

R. Gordon and J. Riedl. (1997). GroupLens: applying

collaborative filtering to Usenet news. Communication

ACM 40(3), pp. 77-87.

Kotler, P., K. Keller, M. Brady, M. Goodman, and T.

Hansen, (2013). Marketing Management, European

Perspective, Pearson Education Limited, Essex.

Lucintel, A. (2012). Global book industry 2012-2017:

www.lucintel.com/reports/media_entertainment/global

book_industry_2012_2017_trends_foreacast_june_20

12.aspx, accessed March 4, 2013.

McLaughlin, K., (2012). kevinomclaughlin.com/2012/02/

26/survey-of-a-genre-science-fiction-ebook-market-

under-the-microscope/, accessed March 5, 2013.

Pazzani, M. J. (1999). A Framework for Collaborative,

Content-Based and Demographic Filtering, Artificial

Intelligence Review. 13(1), pp. 393-408.

Postrel, V. (2007). A small circle of friends, Forbes, 179

(10), p. 11.

Research and Markets, (2011). eBook Publishing &

eReading Devices: 2011 to 2015, www.

researchandmarkets.com/research/59cb8b/ebook_publi

shing, posted October, accessed January 7, 2013.

Rice, A., (2012). The 99¢ Bestseller, Time Magazine,

December 10, pp. 38-43.

Stommel, Y. G., C. Bechter, C., (2013). Challenges,

Chances and Risk Sharing When Self-Publishing

Ebooks – Research into Author Preferences,

International SAMANM Journal of Marketing and

Management, 1(2).

Stumberger, R., (2012). Die zersplitterte Arbeitskraft, VDI

Nachrichten, Nr. 44, November 2, p.19.

Swanson, G., (2011). Bobo Explores Light: Interactive

Learning E-Book, appsineducation.blogspot.com

/2011/09/bobo-explores-light-interactive.html,

accessed February 21, 2012.

Velamuri, J., (2012). Open innovation. Leipzig Graduate

School of Management working paper.

Wingfield, N., (2012). E-Books initiative enlists

publishers to help Africa, International Herald

Tribune, September 8-9, p.18.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

170