A Supply Chain Strategy Management Model for Small and

Medium Sized Enterprises

Madani Alomar and Z. J. Pasek

Industrial and Manufacturing Systems Engineering, University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada

Keywords: Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, AHP, SCOR Model, Supply Chain Strategy, Performance Measurement

System, Dynamic Strategy.

Abstract: This paper proposes a model that will assist companies, particularly the small and medium-sized enterprises,

assess their performance by prioritizing performance measures and selecting an adequate operations strategy

under various market scenarios. The outlined model utilizes and integrates the Supply Chain Operations

Reference framework and the Analytical Hierarchy Process approach to construct, link, and assess a four level

hierarchal structure. The model also helps small and medium-sized enterprises put more emphasis on supply

chain operations and management. The use and benefits of the proposed model are illustrated on a case of a

family owned, medium-sized manufacturing company.

1 INTRODUCTION

Manufacturers today are faced with complex global

challenges such as low cost competitors, fluctuating

commodity prices, increasing customer expectations,

and volatile economic conditions. The uncertainty

associated with these factors has contributed on one

hand to significant changes in the business

environment resulting in tremendous growth and

opportunities for new markets, and on the other hand

in increased frequency and complexity of challenges

that threaten the operations and survival of firms.

These competitive pressures are driving manufacturing

firms to continuously re-evaluate and adjust their

competitive strategies, supply chains, and

manufacturing technologies in order to improve

performance, compete, and survive long- term.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are

much more vulnerable to these external pressures than

larger companies, thus their responses often fall short,

due to limited resources and capabilities (e.g.,

financial resources, managerial talent, and access to

markets)

Numerous studies have revealed that Small

businesses are extremely susceptible to failures; about

50% of small businesses in Canada and 53% in the

United States fail to survive for more than five years

(Branch, 2012) Several research studies have linked

the success of businesses to the type of performance

measurement system (PMS) used by the firms and to

the successful design and implementation. Other

researchers have considered strategic performance

measurement system as a means to attain competitive

advantage, continuous improvement and ability to

successfully manage changes (Holban, 2009; Cocca

and Alberti, 2009). Despite these results, several

investigators found that many small enterprises

predominantly emphasize financial index only

(Hudson et al., 2001; Hvolby and Thorstenson, 2001;

Gosselin, 2005), neglecting the others.

This paper proposes an approach methodology and

a model that will assist SMEs in building a strategic

and dynamic performance measurement system that

considers two types of supply chain strategies, and the

supply chain performance attributes based on Supply

Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) framework. The

model relies on Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

approach to integrate various market scenarios,

performance attributes and supply chain strategies into

one comprehensive model. Unlike other previous

works where the use of AHP and performance

measures were mainly addressing the selection of best

supplier, vendors, markets or manufacturing

departments, this work discusses the improvement of

one enterprise performance under different market

circumstances and the importance of different

performance measures.

46

Alomar M. and Pasek Z..

A Supply Chain Strategy Management Model for Small and Medium Sized Enterprises.

DOI: 10.5220/0004813700460056

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES-2014), pages 46-56

ISBN: 978-989-758-017-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 PERFORMANCE

MEASURMENT SYSTEMS IN

SMES

Performance measurement is at the core of a control

and management system of an enterprise. It plays a

key role in developing strategic plans and assessing

organizational objectives. It is also important in

assessing business ability to gain and sustain

competitive advantage and directing corrective

adjustments and actions as well (Holban, 2009).

Various researchers have linked the success of

businesses to the type of performance measurement

system used by them and to the successful design and

implementation of the measurement system. Other

researchers have considered strategic performance

measurement system as means to attain competitive

advantage, continuous improvement and ability to

respond to internal and external changes (Cocca and

Alberti, 2009).

In this sense, the performance measurement system

is the instrument to support the decision-making either

for launching, selecting actions or redefining

objectives (Bititci, 1995; Globerson, 1985; Neely,

1999). From a global perspective, performance

measurement system as a multi-criteria instrument

consists of a set of performance expressions or metrics

(Melnyk et al, 2004).

The early generations of performance measurement

models focused extensively on financial and

accounting areas and completely ignored the

operational and other non-financial issues. Currently,

the new generation of performance measurement

models makes a strong effort to be strategically

oriented and to address other performance dimensions

including combination of financial and non-financial

areas (Taticchi, Tonelli, &Cagnazzo, 2010).

Nevertheless, according to Tangen: “these new

approaches have a good academic groundwork and are

theoretically sound but they rarely help with the

practical understanding of specific measures at an

operational level”. This is considered a major obstacle

in implementing multi-dimensional performance

measurement system in small enterprises (Tangen,

2004).

Other researchers have tied the failure of

implementing existing performance measurement

systems in small and medium-sized enterprises to the

following issues:

• Use of models or frameworks originally introduced

for large enterprises, the one size fits all, leads to

implementation failure. (Taticchi et al., 2010).

• Improper use of well-known performance

measurement models and frameworks (Tenhunen,

et al., 2001).

• Informal approach to performance measurement

models and frameworks (no rigorous plan or

execution) (Chennell et al., 2005).

Numbers of studies have revealed that many of the

small and medium-sized enterprises did not achieve

the requirements of a strategic performance

measurement system. For example: (Hudson et al.,

2001) found that all companies under the study had a

surplus of financial measures, but their performance

measurement systems were not derived from strategy,

often unclear with complex or obsolete data, and

historically focused on some outdated measures.

Another empirical survey conducted on 83 Danish

enterprises (Hvolby and Thorstenson, 2001) found that

50% of these enterprises have either only one-

performance indicator such as cost or no performance

indicators in place at all. An additional empirical study

(Gosselin, 2005) revealed that majority of small and

medium sized Canadian manufacturing firms continue

using financial measures.

Despite the recommendations from industrial and

academic experts, the proportion of firms that

implement well-known performance measurement

systems remains low (Gosselin, 2005). The results

indicated that the types of performance measures used

by the SMEs were rarely connected to strategy. The

study also revealed that about 70% of the companies

failed to implement well-known strategic performance

measurement models (Gosselin, 2005). The majority

of SMEs according to the previous studies use

traditional management accounting systems.

Nevertheless, the traditional management

accounting systems and financial measures simply do

not provide the richness of information that allows a

company to remain competitive in today's market

place (Dixon et al., 1990) see also table 1. It is

necessary to understand that the metrics and the

measures that are used in performance measurement

system should have the power to capture the depth of

organizational performance, the measures should

reflect their clear relations with a range of levels of

decision-making such as strategic, tactical, and

operational, the metrics should reflect an acceptable

balance between financial and non-financial measures,

and the measurement system should ensure proper

assignment of measures to the areas where they would

be most suitable.

ASupplyChainStrategyManagementModelforSmallandMediumSizedEnterprises

47

Table 1: Traditional versus no-traditional PMS.

Traditional performance measures Non-traditional performance measures

Based on outdated traditional accounting

system

Based on company strategy

Mainly financial measures Mainly non-financial measures

Intended for middle and higher managers Intended for all employees

Lagging metrics On-time metrics

Do not vary between locations Vary between locations

Do not change over time Change overtime as the needs change

Intended mainly for monitoring performance Intended to improve performance

Not applicable for new advanced technology

and methods, JIT,TQM,FMS

Applicable for new advances technology and

methods: JIT,TQM,FMS

Ignoring continuous improvement Help in achieving continuous improvement

3 SMES AND THE CHALLENGES

Studies show that small and medium-sized enterprises

are distinguished from larger firms by a number of key

characteristics (Hudson, Lean, and Smart, 2001) such

as personalized management with little delegation of

authority, severe resource limitations in terms of

skilled manpower, management and finance, and

flexible structure, reactive or fire-fighting mentality,

informal and dynamic strategies, dependency on small

number of customers, limited markets, and high

potential to innovativeness.

These characteristics are also viewed as challenges

that influence the implementation of well-known

performance measurement systems that are designed

for larger firms in small and medium-sized enterprises

(Garengo et al., 2005).

For example, the dynamic strategy of small

business means that these businesses are more

frequently revising their decisions than the larger

firms. This greatly influences internal operations, and

the relations with customers and suppliers. Such

behaviour requires a better system of control with

higher capability to control effectively and rapidly

reflect these changes and their consequences on the

internal operations as well as the external ones. These

limitations of small manufacturing enterprises

emphasize need for a performance measurement and

control system that effectively reflects key business

operations with fewer but critical measures that are

written in form of an understandable structure, and

flexible enough to fit specific needs of each individual

enterprise and the changeable market conditions as

well.

4 ANALYTICAL HIERARCHY

PROCESS (AHP)

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), introduced in

1970 (Saaty, 2008), has become one of the most

broadly used methods for multiple criteria decision-

making (MCDM). It is a decision approach designed

to assist in the solution of complex multiple criteria

problems in a number of application areas. AHP is a

problem-solving framework, flexible, organized

method employed to represent the elements of a

compound problem, hierarchically (Chen et al., 2006).

It has been considered to be an essential tool for both

practitioners and academic researchers in organizing

and analysing complex decisions (Cheng et al., 2002).

AHP has been extensively used for selection

process such as comparing the overall performance of

manufacturing departments (Rangone, 1996),

manufacturing supply chain (Wang et al., 2005),

benchmarking logistics performance (Chan et al.,

2006), and vendor evaluation and selection (Haq and

Kannan, 2006). More researchers are realizing that

AHP is an effective technique and are applying it to

several manufacturing areas (Wang et al., 2005). AHP

has several benefits (Cheng et al., 2002).

It helps to decompose an unstructured problem into

a rational decision hierarchy.

Second, it can draw out more information from the

experts or decision makers by employing the pair-

wise comparison of individual groups of elements.

Third, it sets the computations to assign weights to

the elements.

Fourth, it uses the consistency measure to validate

the consistency of the rating from the experts and

decision makers

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

48

The AHP procedure to solve a complex problem

involves four steps:

1- Breaking down the complexity of a problem into

multiple levels and synthesizing the relations of the

components are the underlying concepts of AHP

(Cheng and Li, 2001) see figure 1.

2- Pair-wise comparison aims to determine the

relative importance of the elements in each level of

the hierarchy. It starts from the second level and

ends at the lowest. A set of comparison matrices of

all elements in a level of the hierarchy with respect

to an element of the immediately higher level are

built so as to prioritize and convert individual

comparative judgments into ratio scale

measurements. The preferences are quantified by

using a nine-point scale. The meaning of each

scale measurement is explained in table 2.

Decision maker needs to express preference

between each pair of the elements in terms of how

much more one element is important than other

element. Table 3 shows a matrix that expresses

personal judgment and preferences.

3- Relative weight calculation. After the pair-wise

comparison matrix is developed, a vector of

priorities (i.e. eigenvector) in the matrix is

calculated and is then normalized to sum to 1.0.

This is done by dividing the elements of each

column of the matrix by the sum of that column

(i.e. normalizing the column). Then, obtain the

eigenvector by adding the elements in each

resulting row to obtain a row sum, and dividing

this sum by the number of elements in the row to

obtain relative weight.

4- Consistency check. A consistency ratio (CR) is

used to measure the consistency in the pair-wise

comparison. The purpose is to ensure that the

judgments of decision makers are consistent. For

example, when using AHP technique, a

consistency ratio between factors and criteria can

be obtained by the following equation:

CR = CI/RI (1)

Where:

CI: consistency index

RI: consistency ratio based on the value of n

Checking consistency provides more information

about the accuracy of the comparison and the decision

alternatives selection. The final score of decision

alternatives can be obtained by applying the following

general equation:

∑∑

1

1

(2)

Where:

S

k

= overall decision of alternative k score

W

i

= relative weight of criteria i

w

ij

= relative weight of indicator j of criteria i

r

ijk

= rating of decision alternative k and for

indicator j of criteria i

n

i

= total number of indicators belong to criteria

Table 2: Comparison scale for the importance using AHP

grading system.

Intensity of

Importance

Definition Explanation

1

Equal

Importance

Two activities/factors

contribute equally to the

objective

3

Somewhat more

important

Experience and judgment

slightly favour one over

the other

5

Strong

importance

Experience and judgment

strongly favour one over

the other

7

Very strong

importance

Experience and judgment

very strongly favour one

over the other. Its

importance is

demonstrated in practice

9

Absolutely

extremely

important

The evidence favouring

one over the other is of the

highest possible validity

2 , 4 , 6 , 8

Intermediate

values

When compromise is

needed

Reciprocal Opposite value

When activity I has one of

the above numbers

assigned to it with activity

j, then j has the reciprocal

value when compared to I.

Source: Saaty(2008)

Table 3: Pair-wise comparison for n number of elements at

the same level.

I1 I2 I3 In

I1 1 2 4

I2 0.5 1

I3 0.25 1

In 1

5 SCOR PERFORMANCE

LEVELS AND ATTRIBUTES

Supply Chain Council (SCC) is a global non-profit

organization formed in 1996 to make and evolve a

standard industry process reference model of the

supply chain for the benefits of helping enterprises

improve supply chain operations. SCC has established

the supply chain framework- the (SCOR) process

ASupplyChainStrategyManagementModelforSmallandMediumSizedEnterprises

49

reference model- for evaluating and comparing supply

chain activities and related performance (supply-

chain.org, 2013). The SCOR model consists of

standard supply chain processes, standard performance

attributes and metrics, standard practices and standard

job skills.

SCOR model divides the supply chain attributes

into two categories: internal and customer related

attributes. The SCOR performance attributes such as:

Supply Chain Reliability, Responsiveness, and Agility

are considered as customer related attributes. Cost and

Assets management are internal attributes. The SCOR

performance section consists of two types of elements:

Performance Attributes and Performance Metrics.

A performance attribute is a combination of

characteristics used to express a strategy. However, an

attribute itself cannot be measured, it is used to set and

identify strategic direction. The metrics that are

assigned to each performance attribute measure the

ability of the supply chain to achieve these attributes.

Table 4 shows five performance attributes; two of

them (the cost and assets management) are considered

as internal-focused. Reliability, Responsiveness, and

Agility are considered as Customer-focused.

Associated with the performance attributes are the

level 1 strategic metrics. These level 1 metrics are the

calculations by which an organization can measure

how successful it is in achieving its desired position

within the competitive market.

Table 4: SCOR performance attributes and definitions.

Performance Attribute Definition

Internal

Costs: CO

The cost of operating the

supply chain processes.

Assets management:

AM

The ability to efficiently utilize

assets

Customer

Reliability: RL

The ability to perform tasks and

activates as planned or

expected. It focuses on the

outcomes of the processes

Responsiveness: RS

The speed at which tasks and

activities are performed

Agility: AG

The ability to respond to

external effects, i.e. demand

and supply uncertainties.

For example, the performance attribute supply

chain cost includes two types of costs: supply chain

management cost and cost of goods sold. Reliability

on the other hand involves only perfect order

fulfilment. Each of level one strategic metric also

divided to level 2 and 3 metrics, more information

about SCOR performance attributes can be found at

Supply Chain Council website (supply-chain.org).

However, the framework does not provide users

and practitioners with any guidelines on how to use or

where to start the evaluation that requires another tool

that simplify such a complex framework.

6 THE APPROACH

Since business conditions became more unpredictable

and unstable, manufacturing firms are required to

adjust their operations strategies in order to meet these

changes. The evaluation of the alternative supply chain

strategies; effective or responsive requires that the

performance of the strategies on agility, reliability,

responsiveness, cost, to be re-evaluated, re-prioritized,

quantified and aggregated to capture the new business

goals. However, this process is not a straightforward

task, since the performance and strategy evaluation

process depends on many factors that by nature are

interconnected and require a specific level of skill and

qualifications that mostly do not exist in many SMEs.

Successful performance measuring systems have to

satisfy and completely fulfil the following points:

The metrics used in performance measurement

systems should have the power to capture and

represent the organizational performance.

The measures need to convey clear connections

with a range of levels of decision-making such as

strategic and operational.

The metrics should also need to reflect an

acceptable balance between non-financial and

financial measures,

A measurement system that ensures a suitable

allocation of metrics to the areas where they would

be most appropriate.

Therefore, the framework outlined in this paper helps

SMEs construct and build a strategic performance

measurement system which involves the two types of

supply chain strategies: Efficient and Responsive, and

supply chain performance attributes based on SCOR

model.

The framework utilizes AHP approach to integrate

SCOR performance attributes, and the two types of

supply chain strategies into one comprehensive model,

(figure 1). The supply chain model is use for several

reasons. First, SMEs need to think and act relying on a

wider range of measures that covers financial and non-

financial issues.

Secondly, this effort aims at bridging the gap

between supply chain models and SMEs. For example,

a study (Arend and Winsner, 2005) revealed that there

is a poor fit between supply chain management and the

small and medium-sized enterprises. The authors

attributed this poor fit to variety of reasons such as

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

50

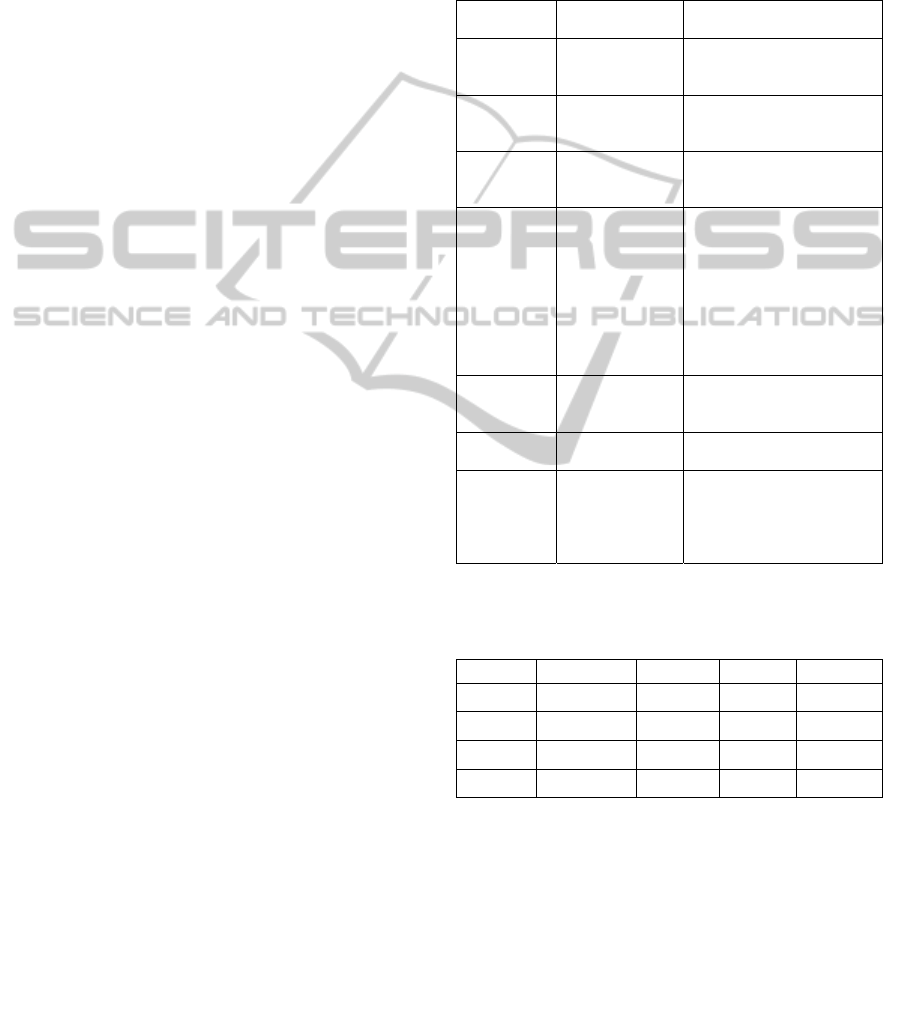

Figure 1: The four levels structure of the model.

improper implementation of supply chain management

by the small and medium-sized enterprises, and due to

the lack of use of supply chain management to

complement strategic focus.

The Expert Choice software was used to assist us

in building the hierarchal structure of the company’s

overall goal, market scenarios, performance attributes

and supply chain strategies. Expert Choice is intuitive,

graphically based and structured in a user-friendly

fashion so as to be valuable for conceptual and

analytical thinkers, novices and category. Expert

Choice software is intended to help decision-makers

and the software users overcome the limits of the

human mind to synthesize qualitative and quantitative

inputs from multiple stakeholders. The Expert Choice

software:

Conveys structure and measurement to the

planning and budgeting process

Aids you determine strategic priorities and

optimally allocates business resources

Converses priorities and builds consensus

Documents and justifies strategic decisions

Enables you to move forward quickly and

confidently (Expert Choice, 2013)

The AHP and Expert Choice software engage decision

makers in structuring a decision into smaller parts,

proceeding from the goal to objectives to sub-

objectives down to the alternative courses of action.

Decision makers then make simple pairwise

comparison judgments throughout the hierarchy to

arrive at overall priorities for the alternatives. The

decision problem may involve social, political,

technical, and economic factors. (Expert Choice,

2013).

The model is illustrated in the next section on a

case of a medium-sized manufacturing enterprise.

As shown in figure1, two key supply chain

strategies are considered at the last level that

represents the available alternatives that the decision

maker has to choose from based on market conditions,

business environment and company’s overall goal. The

third level, the attributes level, includes: Cost, Assets

management as internal or let us say financial

attributes and Agility, Reliability, and Responsiveness

as customer or nonfinancial performance and strategy

attributes. Notice that the SCOR attributes bring

financial and non-financial measures together to

achieve an important part of the non-traditional

performance system requirements. The second level or

the scenario level shows various market conditions:

low demand, average demand and high demand. Each

and every business encounters one or more of these

market conditions, but the question of how, when, and

why one supply chain strategy is chosen over the other

and on what basis usually remains fairly open. Some

of these issues will be highlighted in the next section

through the presented case study.

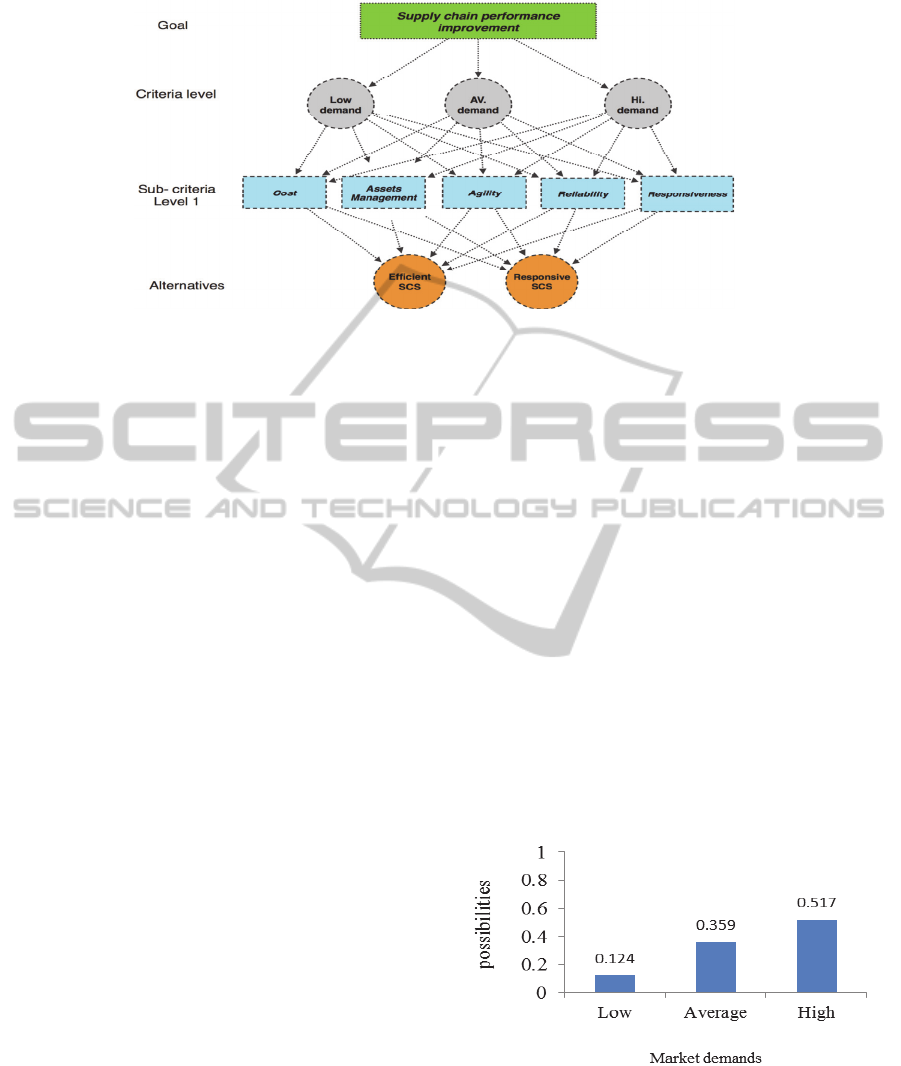

Figure 2: The likelihood of different scenarios.

7 CASE STUDY

A Saudi-based and family-owned medium-size

manufacturing firm, call it company X, specialized in

ASupplyChainStrategyManagementModelforSmallandMediumSizedEnterprises

51

production of plastic pipes and fittings products. The

company strategy is to produce and deliver high

quality products to its customers at the agreed delivery

time and method. Most of its customers are large

firms, mega project contractors and government

agencies. Although the company operates in a highly

competitive market, the plastic pipes and fittings

market, its product prices are almost the highest

compared to similar products on the market.

Based on the information collected about the

company policy and operations, the Expert Choice

software was used to translate and build the four level

hierarchal structures: the goal, scenarios, criteria, and

alternatives levels. The evaluation of these alternative

strategies is carried out level-by-level, starting from

top down towards the lower levels. The process begins

on level two by assessing likelihood of occurrence of

scenarios of different market demands during the

planning period. The evaluation process of different

scenario according to company X is shown in table 5.

Table 5: Pair wise comparison at level 2.

Low Av. High

Low 1 4 3

Av. 1/4 1 2

High 1/3 1/2 1

The results of the second level evaluation process

show that the possibility of high demand scenario

occurrence is relatively higher than the other ones,

figure 2.

The second step evaluates the relative effects of

each criterion “attribute” on performance under a

specific scenario. For example, what would be the

relative effect of cost (CO), assets management (AM),

agility (AG), reliability (RL), and responsiveness (RS)

on performance if demand is low?, see table 6. Notices

that the relative effects of each performance attribute

or criterion may vary depending on market conditions

or product types.

Table 6: The pair wise comparison of performance attributes

under low market demand.

CO AM AG RL RS

CO 1 3 4 3 4

AM 0.33 1 3 2 2

AG 0.25 0.33 1 3 4

RL 0.33 0.50 0.33 1 1

RS 0.25 0.50 0.25 1 1

The results obtained from the evaluation process of

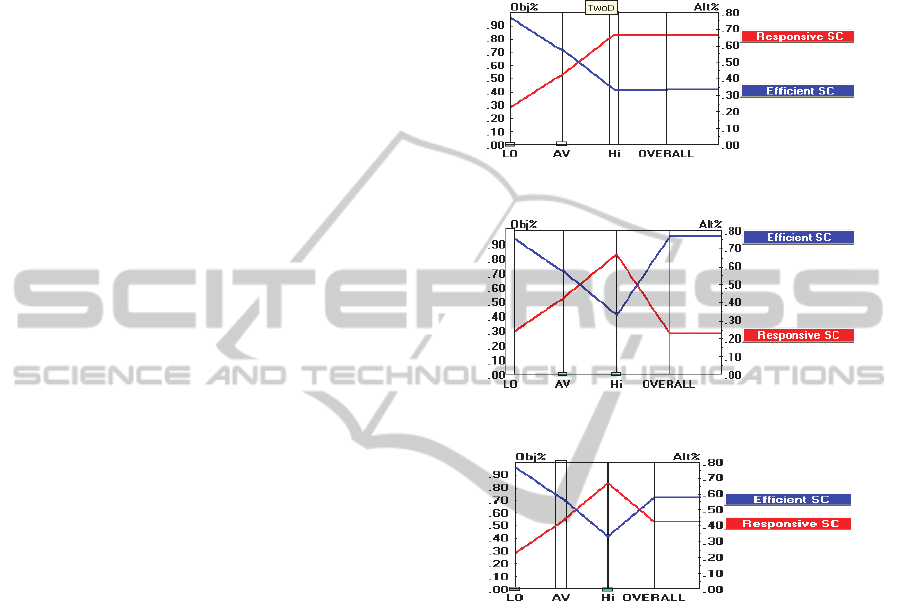

performance attributes are shown in figure 3. In order

to complete the level calculations one needs two more

comparison processes for average and high market

demand. The third step addresses the performance of

each strategy on each performance criterion.

Figure 3: Weights of performance attributes under low

market demand.

Finally, the overall performance of each strategy

can be calculated through the composition process by

using Expert Choice. The performance of the two

alternatives: efficient and responsive supply chain

strategy is shown in the following figure.

Figure 4: Overall weight of the two alternatives.

8 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The proposed framework was used to develop a model

for a specific medium-sized manufacturing company.

Notice that the company expectations of having high

demand for the plastic pipes and fittings products is

about 52%, 36% for average demand and 12% for low

demand during the planning period. With high market

demand, customers usually pay less attention to

products prices and manufacturers without difficulty

cover fixed and other related costs in mass production

environment. This means that the company must place

more emphasis on customer-related attributes as a

major performance success factors.

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

52

Within the planning period, the evaluation process

clearly shows that focus on responsiveness is the most

appropriate strategy that company X needs to adopt

since the possibility of having high demand is

relatively higher than the others. However,

maintaining forever the same performance measures or

supply chain will not help in rapidly changing business

environment.

As the external environment changes frequently

and rapidly, the group of performance attributes and

measures in use by businesses must also change to

reflect the changes in internal and/or external

environment. Generally speaking, the changes in the

performance measurement system can be done by

adding, eliminating, replacing, or even reprioritizing

performance measures and metrics. For example, a

performance measure such as, for example supply

chain responsiveness which initially has high priority

may move down to low priority in other circumstances

or because of changes in the internal and external

business environment.

In the case presented, the judgments of the

likelihood of having high, average and low demand are

based on previously collected information about the

market demands of company X in the last few years.

However, the demand may change at any time during

the planning period which in some cases leads to

remarkable increase or decrease of the real market

needs. These types of changes usually call for

adjustments in businesses strategies, policies, or goals

in order to meet the new challenges. For this reason,

sensitivity analyses to evaluate changes in scenarios

during planning period of company X were used.

The model remains as is with the same scenarios of

market demands: low, average, and high in the second

level. The third level has five supply chain

performance attributes: cost, assets management,

agility, reliability, and responsiveness. And finally in

fourth level provides a choice between two types of

supply chains: efficient or responsive.

Some changes were made to the input data and

judgments of level 2, the market scenarios level. For

example, the likelihood of having high demand was set

to 100% in order to capture and observe the changes in

the model outputs. The 100% high demand market

resulted in selection of responsive supply chain

strategy with about 0.66 priority weights as shown in

figure 5 below.

However, market conditions and demands always

change, thus companies also need to examine the

extremes of the markets. Therefore, the model was

reset to100% low demand. With this setting, the model

chooses efficient supply chain strategy as the best

strategy for the low demand market, see figure 6.

Similar steps were conducted to reset the model to

100% average demand. With this setting, the model

gave the priority to efficient supply chain strategy but

with less weight compared to 100% low demand

scenario, figure 7.

Figure 5: When occurrence of high demand is 100%.

Figure 6: When the event of low demand is 100%.

Figure 7: When average demand is 100%.

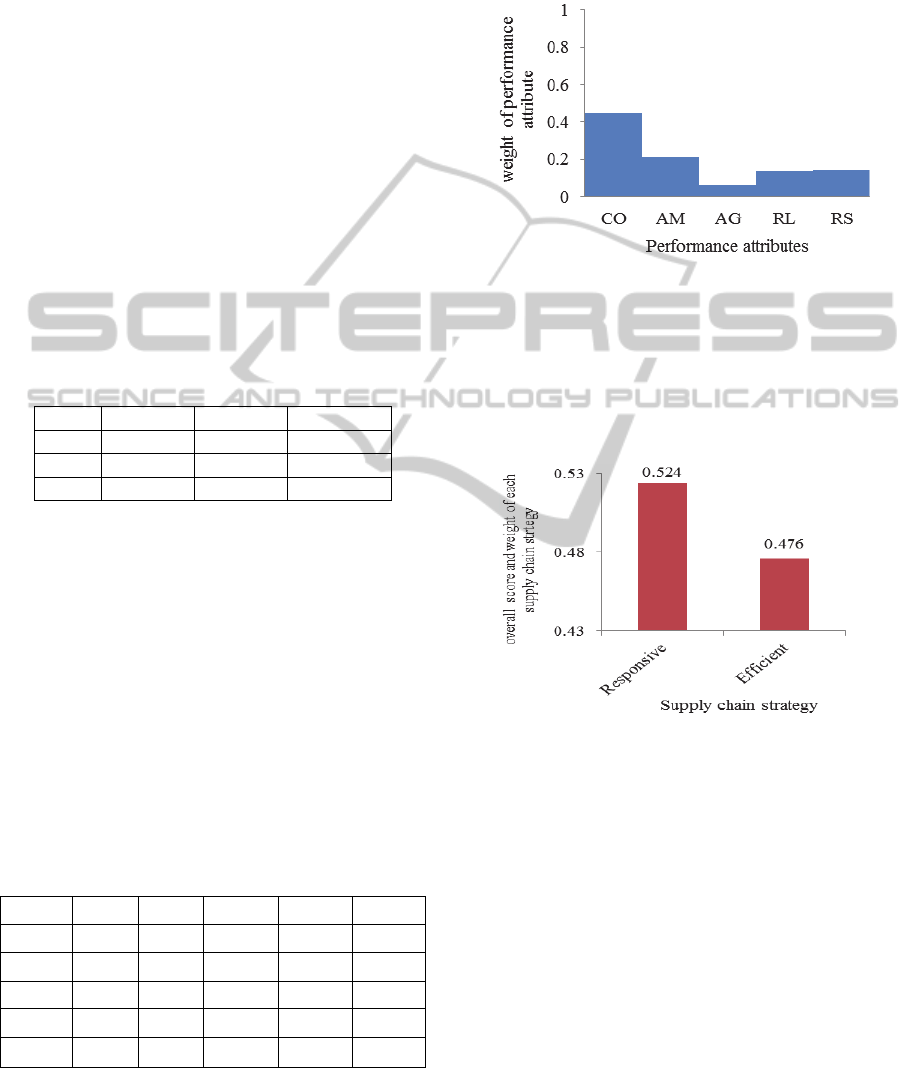

Table 7 shows the results of different scenarios

generated using sensitivity analysis using Expert

choice. In general, when the probability of the

occurrence of low or average demand is 100%, the

performance of efficient supply chain strategy will be

better than the performance of responsive supply chain

strategy. When the probability of high demand is

certain, likelihood of 100%, responsive supply chain

strategy should give better performance than efficient

supply chain strategy. For company X, the market

demand can be divided to three intervals or classes:

low, average, and high. In addition, the company sets

the limits for each one as shown in table 8 below.

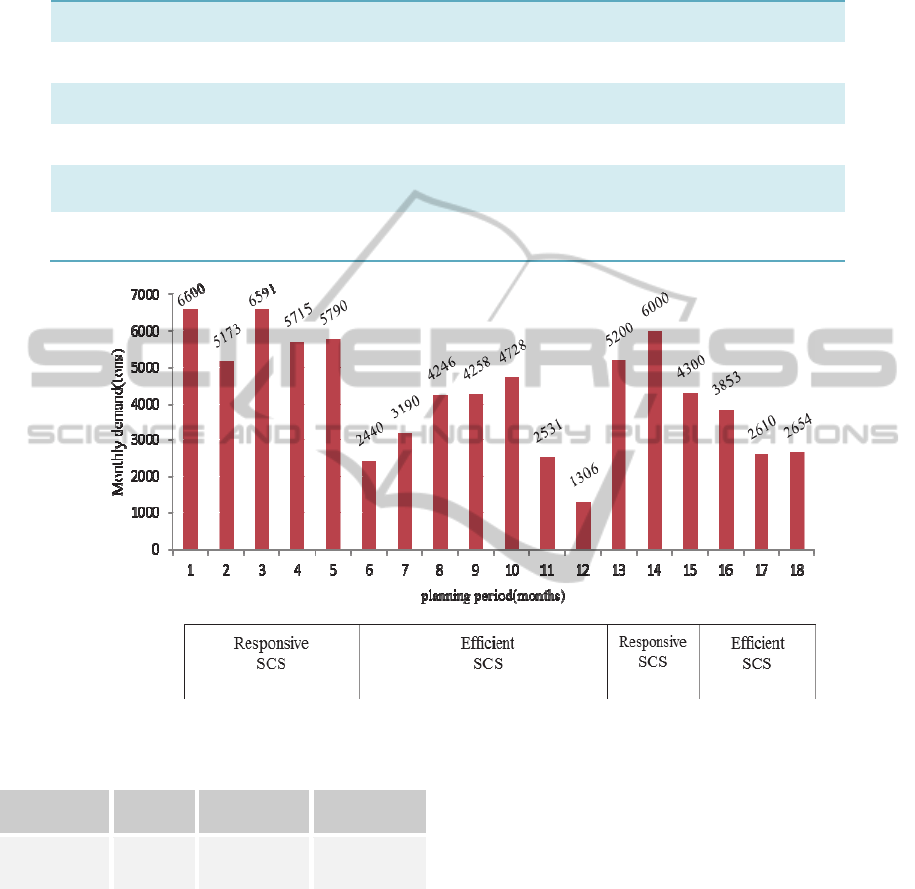

Based on these intervals and the forecasted demand

for the planning period, the coming 18 months, the

company has to adopt both strategies but in different

time periods as shown in figure 8. The company needs

to adopt responsive supply chain strategy for the first

five months within the planning period and go back to

efficient supply chain for the rest of the year.

ASupplyChainStrategyManagementModelforSmallandMediumSizedEnterprises

53

Table 7: Different scenarios call for differing supply chain strategies.

Prob.Low Prob.AV. Prob.Hi PriorityEfficient

Priority

Responsiveness

StrategytoAdopt

0.124 0.359 0.517 0.474 0.526 Responsive

1.00 0.00 0.00 0.768 0.232 Efficient

0.00 1.00 0.00 0.573 0.427 Efficient

0.00 0.00 1.00 0.333 0.667 Responsive

0.379 0.00 0.621 0.500 0.500 Either

0.386 0.00 0.614 0.502 0.498 Efficient

Figure 8: Forecasted market demand of company x and the selection of the supply chain strategy.

Table 8: Demand categories for company x.

Demand Low Average High

Weight

(Tons)

0-2499 2500-4999 5000-8000

The Fisher’s framework suggests that there are two

types of products, functional and innovative products

(Fisher, 1997). Based on this classification, he

suggested two types of supply chain strategies that fit

each product type. For instance, he recommended

efficient supply chain strategy for functional products,

and a responsive supply chain for innovative types of

products.

Although efficient supply chain strategy performs

well with functional products, i.e. plastic pipes and

fittings, our case shows that there are few months

within the planning period that require some degree of

responsiveness in order to meet customer orders,

particularly orders for government projects.

Nevertheless, implementation of the model

requires users to be aware of the difference between

the two strategies. For instance, in the presented case

the company needs to minimize inventory to lower the

cost during low demand time. It also needs to select

material suppliers based on cost as a main factor while

trying to reduce manufacturing costs and lower the

margins. On the other hand (during high demand

period), the company has to reduce lead time, put

higher price margins, respond quickly to demand and

select suppliers based on flexibility, speed and

reliability. Table 9 shows the general differences and a

comparison between the two strategies.

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

54

9 CONCLUSIONS

A quantitative model for performance measurement

system with the example used illustrates how

practitioners especially in SMEs can implement the

model in order to improve business performance.

Using SCOR model helped in identifying a set of

financial and nonfinancial performance measures that

are generally used to evaluate supply chain

performance in large firms. The use of AHP approach

was useful in structuring the model to four levels:

Overall goal, Scenarios, Criteria, and Alternatives.

Table 9: Characteristics of efficient and responsive supply

chain strategies.

Efficient Supply

Chain

Responsive Supply

Chain

Primary goal Supply demand

at lowest cost

Respond quickly to

demand

Product design

strategy

Max.

Performance at a

min. product cost

Create modularity to

allow postponement

of product

differentiation

Pricing strategy Lower margins

because price is a

prime custom

driver

Higher margins

because price is not

a prime customer

driver

Manufacturing

strategy

Lower costs

through high

utilization

Maintain capacity

flexibility to buffer

against

demand/supply

uncertainty

Inventory

strategy

Min. inventory to

lower cost

Maintain buffer

inventory to deal

with demand/supply

uncertainty

Lead time

strategy

Reduce, but not

at the expense of

costs

Reduce

aggressively, even if

the cost are

significant

Supplier strategy Select based on

cost and quality

Select based on

speed, flexibility,

reliability, and

quality

Source: (Chopra and Meindle, 2004)

The use of Expert Choice software facilitated an

excellent environment in structuring the model

hierarchically, carrying out evaluation by level, and

making final alternatives evaluation and selection.

Some sensitivity analyses were performed in order to

sense the difference when changes occur in the internal

or external environment through our model. We

witnessed through the case that the link between

product type and supply chain strategy type works very

well which proofs previous suggestions. We also

observed that adding market demands with three

different scenarios into the model provides us with

different results for one market scenario, which

suggests that there are two key players in strategy

selection and that are the product type and the market

demand.

The authors of this paper believe that the outlined

model achieves important directions of non-traditional

performance measurement system such as: flexibility,

easy to use, up to date, comprehensive, involves

financial and non-financial measures, and based on

business strategy as well. Unlike previous

implementations of AHP and performance measures

model, the proposed model introduced a new approach

that SMEs can use to evaluate their internal needs and

external requirements by combining the two

approaches correctly.

The proposed model also effectively engages users,

mainly SMEs, to the world of supply chain

management and operations.

REFERENCES

Arend, R. and Wisner, J. 2005. Small business and supply

chain management: is there a fit? Journal of business

venture, 20 pp. 403-436.

Bititci, U. 1995. Modelling of performance measurement

systems in manufacturing enterprises. Journal of

production economics, 42 (2), pp. 137-147.

Branch, S. 2012. Key Small Business Statistics - SME

Research and Statistics. [online] Available at:

http://ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/eng/h_02689.html

[Accessed: 25 Sep 2013].

Chen, K., Huang, M. and Chang, P. 2006. Performance

evaluation on manufacturing times. The International

Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 31 (3-

4), pp. 335-341.

Cheng, E. and Li, H. 2001. Analytic hierarchy process: an

approach to determine measures for business

performance. Measuring Business Excellence, 5 (3), pp.

30-37.

Cheng, E., Li, H. and Ho, D. 2002. Analytic hierarchy

process: A defective tool when used improperly..

Measuring Business Excellence, 6 (4), pp. 33-37.

Chennell, A., Dransfield, S., Field, J., Fisher, N., Saunders,

I. and Shaw, D. 2005. "OPM: A system for

organizational performance measurement", paper

presented at Performance Measurement in Past, Present

and Future, Cranfield: Cranfield University, Cranfield:

pp. 96-103.

Chopra, S. and Meindl, P. 2004. Supply chain management.

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice-Hall.

Cocca, A. and Alberti, M. 2009. "SME's Three step

Pyramid: A new performance measurement framework

for SMEs", paper presented at 16th International Annual

EUROMA Conference: Implementation–realizing

Operations Management Knowledge, Göteborg.

Dixon, J., Nanni, A. and Vollmann, T. 1990. "The new

performance challenge: Measuring operations for world-

class competition", paper presented at Business One,

Homewood, IL, Dow Jones-Irwin.

ASupplyChainStrategyManagementModelforSmallandMediumSizedEnterprises

55

Expert Choice. 2013. Collaboration and Decision Support

Software for Groups & Organizations. [online]

Available at: http://expertchoice.com [Accessed: 7 Oct

2013].

Fisher, M. 1997. What is the right supply chain for your

product?. Harvard business review, 75 pp. 105-117.

Garengo, P., Biazzo, S. and Bititci, U. 2005. Performance

measurement systems in SMEs: a review for a research

agenda. International journal of management reviews, 7

(1), pp. 25-47.

Globerson, S. 1985. Issues in developing a performance

criteria system for an organization. International Journal

of Production Research, 23 (4), pp. 639--646.

Gosselin, M. 2005. An empirical study of performance

measurement in manufacturing firms. International

Journal of Productivity and Performance Management,

54 (5/6), pp. 419-437.

Haq, A. and Kannan, G. 2006. Fuzzy analytical hierarchy

process for evaluating and selecting a vendor in a supply

chain model. The International Journal of Advanced

Manufacturing Technology, 29 (7-8), pp. 826-835.

Holban, I. 2009. "Strategic performance measurement

system and SMEs competitive advantage", paper

presented at International conference on economics and

administration, University of Bucharest, Romania,

Bucharest: Faculty of administration and businesses.

Hudson, M., Lean, J. and Smart, P. 2001. Improving control

through effective performance measurement in SMEs.

Production planning \& control, 12 (8), pp. 804-813.

Hvolby, H. and Thorstenson, A. 2001. "Indicators for

performance measurement in small and medium-sized

enterprises", paper presented at the Institution of

Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering

Manufacture, pp. 1143-1146.

Melnyk, S., Stewart, D. and Swink, M. 2004. Metrics and

performance measurement in operations management:

dealing with the metrics maze. Journal of Operations

Management, 22 (3), pp. 209-218.

Neely, A. 1999. The performance measurement revolution:

why now and what next? International Journal of

Operations & Production Management, 19 (2), pp. 205-

228.

Rangone, A. 1996. An analytical hierarchy process

framework for comparing the overall performance of

manufacturing departments. International Journal of

Operations \& Production Management, 16 (8), pp. 104-

119.

Saaty, T. 2008. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy

process. International Journal of Services Sciences, 1

(1), pp. 83--98.

Supply-chain.org. 2013. SCOR | Supply Chain Council.

[online] Available at: http://supply-chain.org/scor

[Accessed: 25 Sep 2013].

Tangen, S. 2004. Performance measurement: from

philosophy to practice. International Journal of

Productivity and Performance Management, 53 (8), pp.

726-737.

Taticchi, P., Tonelli, F. and Cagnazzo, L. 2010. Performance

measurement and management: a literature review and a

research agenda. Measuring Business Excellence, 14 (1),

pp. 4-18.

Tenhunen, J., Rantanen, H. and Ukko, J. 2001. "SME

oriented implementation of performance measurement

system", working paper, Lappeenranta University of

Technology, Lahti, Finland: Department of Indutrial

engineering and management.

Wang, G., Huang, S. and Dismukes, J. 2005.Manufacturing

supply chain design and evaluation. The International

Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 25 (1-

2), pp. 93-100.

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

56