Comparing Electronic Examination Methods for Assessing

Engineering Students

The Case of Multiple-Choice Questions and Constructed Response Questions

Dimos Triantis, Errikos Ventouras, Ioanna Leraki, Charalampos Stergiopoulos,

Ilias Stavrakas and George Hloupis

E-learning Support Team, Technological Educational Institute of Athens, Ag. Spyridonos, Egaleo, Athens, Greece

Keywords: Assessment Methodologies, Computer-aided Examination Methods, Evaluation Algorithms, Undergraduate

Engineering Modules, Scoring Rules, Multiple Choice Questions, Constructed Response Questions.

Abstract: The aim of this work is the comparison of two well-known examination methods, the first consisted of

multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and the second based on constructed-response questions (CRQs). During

this research MCQ and CRQ tests were created for examining the undergraduate engineering module of

“project management” and were given to a group of students. Computers and a special software package

were used to support the process. During the first part the examinees had to answer a set of CRQs.

Afterwards, they had to answer a set of MCQs. Both sets covered the same topics and had the same level of

difficulty. The second method (MCQs) is more objective in terms of grading, though it may conceal an error

in the final formulation of the score when a student gives an answer based on an instinctive feeling. To

eliminate this problem a set of MCQs pairs was composed taking care that each question of the pair

addressed the same topic in a way that the similarity would not be evident to a student who did not possess

adequate knowledge. By applying a suitable scoring rule to the MCQs, very similar results are obtained

when comparing these two examination methods.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modern IT can provide a set of tools for the

enhancement of the educational process such as

material of digital polymorphic content and software

applications (Reiser & Dempsey, 2011; Dede, 2005;

Friedl et al., 2006). The penetration and

incorporation of such tools in the modern academic

learning practice has been widely accepted since

many years (DeBord et al., 2004). It can potentially

contribute to the enrichment of the traditional

examination and assessment methods of students by

the use of computer aided systems and the

introduction of innovative examination techniques

(Tsiakas et al., 2007).

Multiple Choice Question (MCQs) tests belong

to the category of objective evaluation methods as

the score can be rapidly calculated without putting

the examiner in the position of deciding the grade.

Moreover, it does not depend upon the writing speed

and skill of the examinee (Bush, 2006; Freeman&

Lewis, 1998; Scharf & Baldwin, 2007). The time

efficiency, combined with the grading objectivity,

enables the provision of prompt feedback to the

examinee, after the termination of the examination,

regarding the overall score along with specific

information in a form of report about correct and

incorrect answers.

A significant problem of the MCQs is the

infiltration of the “guessing” factor during the time

of selecting one of the possible answers. The

application of a simple grading rule of positive score

only for the correct answers and no loss for the

incorrect ones could form a score that a part of it

may be based on guessing or sheer luck and does not

objectively reflect the student’s knowledge. A

potential solution to this problem can be the

application of special grading rules that may include

a penalty (i.e. subtraction of points) in case of wrong

answer (Scharf & Baldwin, 2007). This fact can

affect the students’ behavior and mislead them in

terms of decision making. Their uncertainty will

eventually generate variance regarding the test

scores which is related to the expectations of the

examinees and not to the knowledge that is tested

126

Triantis D., Ventouras E., Leraki I., Stergiopoulos C., Stavrakas I. and Hloupis G..

Comparing Electronic Examination Methods for Assessing Engineering Students - The Case of Multiple-Choice Questions and Constructed Response

Questions.

DOI: 10.5220/0004848401260132

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 126-132

ISBN: 978-989-758-020-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

(Bereby-Meyer et al., 2002; Bereby-Meyer et al.,

2003).

One of the most widely used examination

methods include sets of constructed-response

questions (CRQs). These questions request as an

answer a short text or essay. The answer is evaluated

and graded by the examiner. Previous works exhibit

that MCQs have the same validity as the ones

coming from CRQs tests and they are at the same

time highly reliable (Lukhele et al., 1994; Wainer &

Thissen, 1993; Wainer & Thissen, 2001). There are

two works (Ventouras et al., 2010; Triantis &

Ventouras., 2011) that compare the results coming

from both methods (CRQs and MCQs) that are

statistically identical when using a special grading

rule applied to the MCQs examination. Another

work (Ventouras et al., 2011) is comparing oral

examination and MCQs examination using the same

special grading rule. The modules that the method

was applied were core engineering courses thus

there was a great interest to objectively evaluate

students in order to identify any potential gaps in

their knowledge that may affect their further studies.

This method is based on the formulation of

questions in pairs. Every pair addressed the same

topic in a way that this fact is not evident to the

student that did not possess adequate knowledge. A

cumulative grade for the pair is calculated including

bonus points if both questions are answered

correctly or subtracting points as a penalty if one

question is answered correctly. The aim of that

scoring rule is to penalize guessing, in a way that

might not positively induce the dissuading effects

mentioned above, which are related to the negative

marking part of the commonly used mixed-scoring

schemes.

The aim of the present work is to further

investigate the similarity of results when applying

both methods in another engineering course and

exploit the possibilities offered by the use of IT in

the educational process. An objective of this work is

to use MCQs examination methods, in conjunction

or alternatively, with examination methods which

are not suited for the PC environment, such as CR

tests.

This study belongs to an ongoing research

framework regarding assessment methods and

parameters that can be potentially used as reliability

and validity markers of the examination methods.

There exist substantial indications that MC scores

provide higher reliability and are as valid as scores

extracted from examinations based on the CRQs

method (Wainer & Thissen, 1993; Lukhele, Thissen,

& Wainer, 1994). These indications would help in

promoting the use of MCQs tests in most

educational settings where CRQs are still used,

especially taking into account the drawbacks of the

CRQs examination as the subjects that might be

examined cannot cover a significant amount of the

material taught during the courses along with their

inherent inability of introducing automated grading

in essay-like responses to questions. Concerning the

interest and motivation of engineering students to

use new technological tools as part of their

educational process an electronic examination will

provide immediate results and could be an essential

enhancement in the context of a larger effort already

began in the Technological Education Institute of

Athens of introducing computer aided and web tools

for supporting teaching. This fact requires research

and well defined methods for creating objective

assessment methods.

2 EXAMINED COURSE AND

SAMPLE OF STUDENTS

During the academic period 2012-2013, a course

was selected, in order to compare the results

produced by both examination methods. The course

is entitled “Project Management” and belongs to the

group of supplementary engineering courses taught

in the Department of Electronics hosted by the

Technological Educational Institute (T.E.I.) of

Athens. The same group of 37 students participated

in both examinations (MCQs and CRQs). All

students had completed the course and polymorphic

material (notes, videos, etc.) in digital format had

been provided to them. Moreover, all students were

familiarized with the electronic examination

platform which would be used for both

examinations. During the CRQs examination the

students had to type their answer intο the appropriate

text field. For the case of MCQs examination the

students had to answer the question by clicking one

of the possible answers. The examination took place

in a PC laboratory room using an application called

“e-examination”. This application had been

implemented in an effort to introduce at the

Technological Educational Institute (T.E.I.) of

Athens, LMS tools to support the educational

process (Tsiakas et al., 2007; Stergiopoulos et al.,

2006).

At the end of the MCQs test an electronic

report was produced for each student. This report

included all questions with the correct answer and

the indication of whether it was correctly or wrongly

answered, as well as the final score. One copy was

given to the student and one to the examiner, for

ComparingElectronicExaminationMethodsforAssessingEngineeringStudents-TheCaseofMultiple-ChoiceQuestions

andConstructedResponseQuestions

127

processing the scores.

For the CRQs examination, a set of twenty (20)

questions was created. The distribution of CRQs was

designed in a way that they covered all topics taught

during the course. Their difficulty level varied and a

special weight in terms of grading was appointed to

each one according to the level of difficulty. The

total score that a student could achieve was 100

points.

For constructing the MCQs examination the

questions were selected by a database that contains a

large number (N=300) of questions which also

addressed all the topics taught during the course. By

using a special software, a first set of MCQs {q

a1

,

q

a2

, …, q

ak

} (k=20) was randomly selected from the

database. Once again, a weight w

ai

was assigned to

each question i=1,…,k, depending on its level of

difficulty. In order to form 20 pairs of questions,

another set was selected from the same database

{q

b1

, q

b2

, …, q

bk

} (k=20). Each pair addressed the

same topic and the knowledge of the correct answer

for question q

ai

, from a student who had performed a

thorough study implied the knowledge of the correct

answer for q

bi

and vice versa. The total score that a

student could achieve was 100 points. The

examiners took special care that both examinations

were of the same level of difficulty in order that the

results could be comparable. During this

examination all questions form pairs in order to

apply the scoring rules in all the set and trying to

eliminate the guessing factor from each and every

one of the questions addressed by the students.

3 SCORING METHODOLOGY

As mentioned above, the CRQ’s examination

includes twenty questions. Each question

corresponds to a certain grade according to its

difficulty. The way that the student answers the

question is evaluated by the teacher. The overall

examination score m1 was extracted, as the sum of

the partial grades, and is by definition normalized to

a maximum value of 100.

For the MCQs the score was calculated as

follows: For each MCQs pair i=1,…,20, the

“paired” partial score p

i

is:

()(1)

i ai ai bi bi bonus

pqwqw k

(1.a)

if both q

ai

and q

bi

were correct (q

ai

=q

bi

=1) or

()(1)

iaiaibibi penalty

pqwqw k

(1.b)

if q

ai

or q

bi

was correct (q

ai

=1 and q

bi

=0, or q

ai

=0 and

q

bi

=1).

0

i

p

(1.c)

if both q

ai

and q

bi

were incorrect, in which case

q

ai

=q

bi

=0.

The parameters k

bonus

and k

penalty

were variables

that are used for the calibration of the bonus/penalty

mechanism applied to the scoring rule. For most

pairs, the questions of the pair had the same weight.

This means that w

ai

=w

bi

.

In some cases though, the weight of the two

paired questions differed slightly (i.e., by 0.5)

because it is not possible for some topics to create a

pair of questions that referred to the same topic and

the knowledge of the correct answer for question q

ai

,

from a student who systematically studied implied

the knowledge of the correct answer for q

bi

and vice

versa and were also absolutely equal in their level of

difficulty.

The total score m2, with maximum value equal

to 100, was then computed as:

20

1

20

1

2

(1 ) ( )

i

i

bonus ai bi

i

p

m

kww

(2)

Therefore, for the calculation of score m2, a

bonus is given to the student for correctly answering

both questions of the pair (q

ai

, q

bi

) and a penalty for

correctly answering only one question of the pair. In

the case that a student left a question unanswered

intentionally or because of running out of time, a

penalty would be given regarding the pair that the

question belonged to. Following this scoring

algorithm, the final score corresponds to the paired

MCQs examination method.

Another scoring method was applied to the same

group of questions. This method is characterized by

a classic scoring rule applied to MCQs

examinations. When a student gave a correct answer

the score that corresponded to this question was

added to the overall one. Otherwise, in case of a

wrong answer, the student got no points at all. This

method ignores any relation existed between the

questions of a pair. Moreover, no penalty or bonus

was considered during the scoring process. The

overall score (m3) for this method was calculated

using the following equation:

20

1

20

1

()

3

()

i

ai bi

i

ai ai bi bi

qw qw

m

ww

(3)

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

128

The weights (w) as well as the points assigned to

each question in case of a correct answer remained

the same. Eq. 3 is a special case of Eq. 2 when k was

omitted.

4 VALIDITY THREATS

Validity is the most important characteristic of

assessment data. The threats to validity are

circumstances or processes that undermine the

assessment. The most important threats to the

validity of the study are discussed below:

The issue of poorly crafted questions is very

significant as writing effective MCQs as well as

CRQs which test important cognitive knowledge is a

demanded task. The teacher should be able to create

sets of questions comprised of the MCQ type

supported by the application. This depends on the

structure of the module and the nature of the

examination topics. The challenge was to

fragmentise big problems and exercises into MC

questions covering at the same time a wide range of

the module topic. The questions can be separated

into groups of different level of difficulty. There was

previous experience in organizing and conducting

electronic examinations for the specific module

(Ventouras et al., 2010).

Various testing irregularities can be that the

students have prior knowledge of the test questions

or that they perform unethical actions (i.e. cheating)

during the examination. Such action can severely

affect the score. Students from the specific

department were more or less accustomed to new

technologies and the use of computers. They were

also familiar with the concept of MCQs examined

electronically and they had access to sample MCQs

tests for self-evaluation purposes. These questions

were not part of the current examination. Moreover,

the software package used for the electronic

examination had the feature to present to each

student’s monitor the set of the questions along with

their corresponding answers in random order. This

way any attempt of cheating or communication

among the examinees could be immediately

apparent by the supervisor.

All students were “testwise” in terms of been

familiar with the MCQ exam process. The teachers

of the module had taken special care during the

construction of the questions in order to create sets

that could not easily answered by guessing. In any

case the “paired questions” concept also contributed

to the solution of this issue.

Test Item Bias refers to the fairness of the test

item for different groups of students. In case that the

test item is biased different group of students have

different probabilities of correctly responding. For

the purposes of the current study the same group of

students took part in both examinations which were

constructed and controlled by experienced teachers

5 RESULTS & DISCUSSION

In the present study the effects of changing the value

of parameter k were investigated. Regarding MCQs

examination Eq. 3 was initially used for the

calculation of the MCQs examination results. This

equation corresponds to the classic scoring rule

meaning that no bonus nor penalty points were taken

into consideration. This simplified scoring rule

produced results that were higher than the ones

produced by the CRQs examination. Apart from the

top scores that well prepared students achieved and

did not present significant differences, all other

scores presented a deviation. A possible explanation

could be the absence of a mechanism that fixed the

“guessing” factor when answering the questions. In

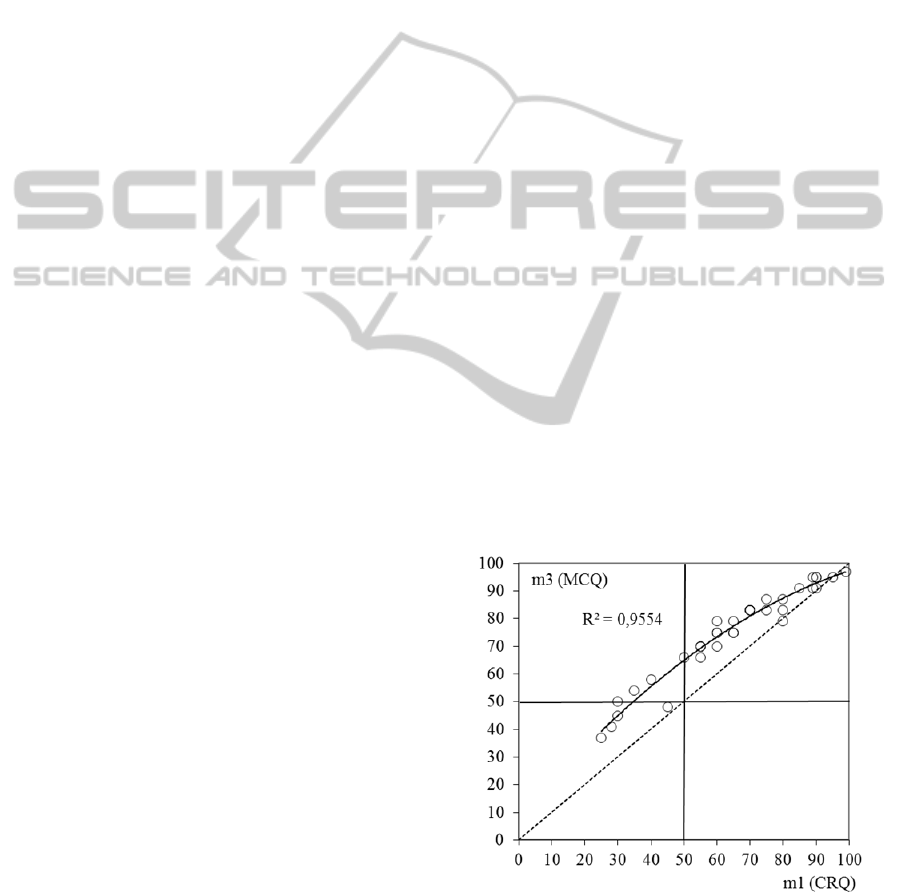

Figure 1 the regression line of score (m1) to score

(m3) are presented. The fitting is based on a second

degree polynomial. It is observed that most students’

scores are above the bisector as shown in Figure 1.

A fit for the score can be quantified using parameter

R

2

which is related to the regression line of CRQ

score of each student (m1) to the MCQ score (m3) of

the same student. Its best possible value is 1. The

value of R

2

for this case is equal to 0.9554.

Figure 1: Regression line of CRQ score of each student

(m1) to the MCQ score (m3).

It must be noted that in order to have comparable

results, students had been informed that incorrect

ComparingElectronicExaminationMethodsforAssessingEngineeringStudents-TheCaseofMultiple-ChoiceQuestions

andConstructedResponseQuestions

129

answers did not have any additional penalty in terms

of negative marking. This way they were

encouraged to attempt answering any questions that

might have a rough knowledge on the topic. During

this examination the students were not aware of the

scoring rule based on paired questions as this

knowledge might be a factor that affect decision

making under uncertainty. In turn, this might

produce variance in the test scores that is related to

the expectations of the examinees and not to the

knowledge that is tested (Bereby-Meyer et al., 2002;

Bereby-Meyer et al., 2003). The final report

produced by the system included only the scores

calculated based on the classic scoring rule meaning

that no bonus nor penalty points were taken into

consideration (m3).

The bias that is probably caused by the

“guessing” factor is clearly corrected when using the

scoring rule of paired questions. This is shown in

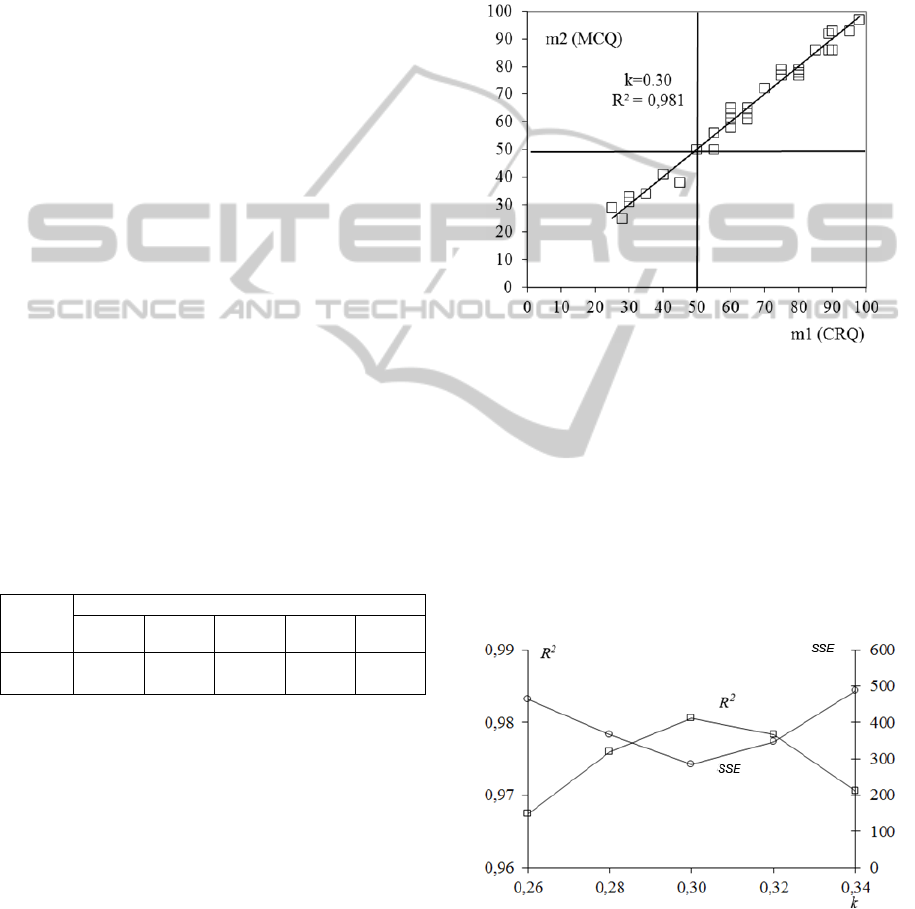

Figure 2 if the regression line is compared to the one

shown in Figure 1. An attempt to find the optimal

values was made in order to have a better fit of the

scores achieved by the examinees during both

examination methods. For this the case the k

bonus

and

k

penalty

parameters are considered as one parameter k.

This means that the same value is assigned to both

parameters. This value is added to the score if the

student correctly answered both questions of the pair

and it is subtracted if the student failed to correctly

answer one question of the pair. The results

produced by the system were only available for the

examiners in order to perform the research.

Table 1: Results of the examination methods.

CRQ

method

MCQ method (paired questions)

k=0.26 k=0.28 k=0.30 k=0.32 k=0.34

64.97 65.50 65.14 65.20 64.70 64.41

In Table 1 the results using CRQs and MCQs

with paired questions are shown. For the MCQs

examination method different values of k parameter

were set when calculating the overall score of each

student using Eq. 2. It is shown that for the

parameter k = k

bonus

= k

penalty

= 0.30 the mean value

of the distribution of scores calculated for the MCQ

method is very close to the mean value of the

distribution of scores of the CRQ method. This is in

agreement with the results of previous electronic

examinations using the Bonus/penalty scoring

methodology (Triantis & Ventouras, 2011). Further

research and more examination results of various

courses are required in order to evaluate the

optimized value parameter k which seems to be

approximately equal to 0.3. A fit for the score can be

quantified using parameter R

2

which is related to the

regression line of CRQ score of each student (m1) to

the MCQ score (m2) of the same student. Its best

possible value is 1. In Figure 2 the regression line of

score (m1) to score (m2) are presented for k=0.30. It

is observed that R

2

remained at a high level (> 0.98)

close to a value equal to 1 for 0.30 ≤ k ≤ 0.34.

Figure 2: Regression line of CRQ score of each student

(m1) to the MCQ score (m2).

A metric related to the variation of the k

parameter value is the sum of the squared

differences of the students’ scores during MCQs

(paired questions) and CRQs examination. The sum

of squared error (SSE) is calculated by the following

equation:

37

2

1

(1 2)

jj

j

SSE m m

(4)

Figure 3: Sum of squared differences of m1 and m2 as

related to k parameter. R

2

related to k parameter.

The optimum value that the sum could have

reached was zero. In Figure 3 is shown that the

function of sum to parameter k is smoothly varying

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

130

within the space of k=0.26 and k=0.34 having a

minimum at k=0.30. This value of k parameter is the

optimum one to apply to the scoring rule. In the

same figure the relation of R

2

to parameter k is also

shown. It is observed that the maximum value of R

2

was also found for k=0.3. This value which seems to

be the optimal one and has been also observed

during the implementation of this method to other

modules already published (Ventouras et al., 2010;

Triantis & Ventouras., 2011) and optimses the

students’ overall score in a way that they objectively

reflect their level of knowledge.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Electronic examinations supported by special

software tools are very helpful for the educational

process as they provide the means for the automatic

production of the results and the ability to easily

apply different scoring rules. This way the lecturer

can have a clear image of the results which may be

used for optimizing the way of teaching and

disseminated material.

During the comparison of the CRQs examination

method and the MCQs examination method it was

observed that the classic scoring rule of positive

score for correct answers introduced a bias due to

the failure of eliminating the “guessing” factor, a

common phenomenon of MCQs examinations.

Therefore, such a simple scoring rule cannot

advance MCQs examination for potentially

substituting a CQRs examination method.

Nevertheless, by applying a scoring rule that

introduces the use of a special parameter that its

value is added or subtracted to the overall score

according to the correct or wrong answers along

with the concept of pairs of questions addressed the

same topic, can give results that are very close to the

ones produced by the CQRs method. To the extent

of the results of the present study, indication is

provided that a value of k parameter approximately

equal to 0.3 can optimally give results that clearly

and objectively reflect the level of student’s

knowledge.

The key factor for applying this rule is a

thorough preparation of the questions from the

examiner in such a way that they cover all topics of

interest and can form pairs in a way that their

relation to a specific topic will not be evident to a

student that is not well prepared.

Part of future work will be the research on results

when assigning different values to k

bonus

and k

penalty

parameters, respectively. During this research an

algorithm might also designed for enhancing the

electronic examination application by automatically

selecting the optimized value of k parameter. The

scoring rule has to be tested in other modules as well

in order to further verify its usefulness as an

objective evaluation tool.

REFERENCES

Bereby-Meyer, Y., Meyer, J., & Flascher, O. M. 2002.

Prospect theory analysis of guessing in multiple choice

tests. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15(4),

pp. 313-327.

Bereby-Meyer, Y., Meyer, J., & Budescu, D. V. 2003.

Decision making under internal uncertainty: The case

of multiple-choice tests with different scoring

rules. Acta psychologica, 11(2), pp. 207-220.

Bush, M. E. 2006. Quality assurance of multiple-choice

tests. Quality Assurance in Education, 14(4), pp. 398-

404.

DeBord, K. A., Aruguete, M. S., & Muhlig, J. 2004. Are

computer-assisted teaching methods effective?,

Teaching of Psychology, 31(1), pp. 65-68.

Dede, C. 2005. Planning for neomillennial learning styles.

Educause Quarterly, 28(1), 7-12.

Friedl, R., Höppler, H., Ecard, K., Scholz, W., Hannekum,

A., Öchsner, W., & Stracke, S. 2006. Multimedia-

driven teaching significantly improves students’

performance when compared with a print medium, The

Annals of thoracic surgery, 81(5), pp. 1760-1766.

Freeman, R., & Lewis, R. 1998. Planning and

implementing assessment. Routledge.

Lukhele, R., Thissen, D., & Wainer, H. 1994. On the

Relative Value of MultipleChoice, Constructed

Response, and ExamineeSelected Items on Two

Achievement Tests, Journal of Educational

Measurement, 31(3), pp. 234-250.

Reiser, R. A., & Dempsey, J. V. 2011. Trends and issues

in instructional design and technology. Pearson.

Scharf, E. M., & Baldwin, L. P. 2007. Assessing multiple

choice question (MCQ) tests-a mathematical

perspective, Active Learning in Higher Education,

8(1), pp. 31-47.

Stergiopoulos, C., Tsiakas, P., Triantis, D., & Kaitsa, M.

2006. Evaluating Electronic Examination Methods

Applied to Students of Electronics. Effectiveness and

Comparison to the Paper-and-Pencil Method.

In Sensor Networks, Ubiquitous, and Trustworthy

Computing, 2006. IEEE International Conference on ,

2, pp. 143-151..

Tsiakas, P., Stergiopoulos, C., Nafpaktitis, D., Triantis, D.,

& Stavrakas, I. 2007. Computer as a tool in teaching,

examining and assessing electronic engineering

students. In EUROCON’07, The International

Conference on "Computer as a Tool", pp. 2490-2497.

Triantis, D., & Ventouras, E. 2011. Enhancing Electronic

Examinations through Advanced Multiple-Choice

Questionnaires. Higher Education Institutions and

ComparingElectronicExaminationMethodsforAssessingEngineeringStudents-TheCaseofMultiple-ChoiceQuestions

andConstructedResponseQuestions

131

Learning Management Systems: Adoption and

Standardization, 178.

Ventouras, E., Triantis, D., Tsiakas, P., & Stergiopoulos,

C. 2010. Comparison of examination methods based

on multiple-choice questions and constructed-response

questions using personal computers, Computers &

Education, 54(2), pp. 455-461.

Ventouras, E., Triantis, D., Tsiakas, P., & Stergiopoulos,

C. 2011. Comparison of oral examination and

electronic examination using paired multiple-choice

questions. Computers & Education, 56(3), pp. 616-

624.

Wainer, H., & Thissen, D. 1993. Combining multiple-

choice and constructed-response test scores: Toward a

Marxist theory of test construction. Applied

Measurement in Education, 6(2), pp. 103-118.

Wainer, H., & Thissen, D. 2001. True score theory: The

traditional method. Test scoring, 23-72.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

132