Playing Cards and Drawing with Patterns

Situated and Participatory Practices for Designing iDTV Applications

Samuel B. Buchdid, Roberto Pereira and M. Cecília C. Baranauskas

Institute of Computing, University of Campinas (UNICAMP),

Av. Albert Einstein N1251, Campinas – SP, CEP 13083-852, Brazil

Keywords: Socially Aware Computing, Organizational Semiotics, Design Patterns, Participatory Design, HCI, iDTV.

Abstract: Making design has become a challenging activity, in part due to the increasingly complexity of the context

in which designed solutions will be inserted. Designing iDTV applications is specially demanding because

of the scarce theoretical and practical references, problems that are inherent to the technology, and its social

and pervasive aspects. In this paper, we investigate the design for iDTV by proposing three participatory

practices for supporting a situated design and evaluation of iDTV applications. A case study reports the use

of the practices in the real context of a Brazilian broadcasting company, aiming at developing an overlaid

iDTV application for one of its TV shows. The practices were articulated in a situated design process that

favored the participation of important stakeholders, supporting different design activities: from the problem

clarification and organization of requirements to the creation and evaluation of an interactive prototype. The

results suggest the practices’ usefulness for supporting design activities, indicate the benefits of a situated

and participatory design for iDTV applications, and may inspire researchers and designers in other contexts.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the last years, the amount and diversity of

technical devices have increased both inside and

outside people’s homes (e.g., tools, mobiles, cars,

airports), being increasingly interconnected (e.g.,

through bluetooth, wireless LAN, 4G) (Fallman,

2011). Systems are not working in isolation, but in

plural environments, bringing different people

together as citizens and members of global

communities (Sellen et al., 2009). As Bannon (2011)

suggests, in this scenario, there are problems that go

beyond the relationship between users and

technologies, requiring more than a man-machine

approach and ergonomic fixes to make useful and

meaningful design.

Therefore, designing interactive systems is

becoming a more complex task, not only in the

technical sense, but also in the social one (Fallman,

2011). However, Winograd (1997) highlights that

the majority of techniques, concepts, methods and

skills to make design for a new and complex

scenario are foreign of the computer science

mainstream. In this sense, it is necessary to look at

the technology comprehensively within the situated

context in which it is embedded, incorporating

knowledge of several stakeholders, areas, subjects

and theories (Harrison et al., 2007).

Within this scenario, the emergency of the

Interactive Digital TV (iDTV) (which includes

digital transmission, receiver processing capability

and interactivity channel) opens up a variety of

possibilities for new services for TV (Rice and Alm,

2008). However, as Bernhaupt et al. (2010) argue,

with new devices connected to TV, watching it has

become an increasingly complicated activity.

In fact, the iDTV has technical issues as well as

social characteristics that influence directly their use

and acceptance. For instance: the interaction limited

by the remote control, the lack of custom of people

to interact with television content, the high amount

and diversity of users, the usual presence of other

viewers in the same physical space, to cite a few

(Kunert, 2009). As Cesar et al. (2008) assert, the TV

is a highly social and pervasive technology —

characteristics that make it a challenging and

interesting field to investigate, but that usually are

not receiving attention from current works.

Despite not abundant, some literature has

proposed ways to support the design of iDTV

applications. Chorianopoulos (2006) analyzed works

on media and studies about television and everyday

14

B. Buchdid S., Pereira R. and Cecília C. Baranauskas M..

Playing Cards and Drawing with Patterns - Situated and Participatory Practices for Designing iDTV Applications.

DOI: 10.5220/0004887100140027

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 14-27

ISBN: 978-989-758-029-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

life, proposing design principles to support user

interactivity during leisure pursuits in domestic

settings. Piccolo et al. (2007) proposed

recommendations to help designers with

accessibility issues for iDTV applications. Kunert

(2009) proposed a collection of pattern for the iDTV

focused in usability issues. Solano et al. (2011)

presented a set of guidelines that should be

considered in iDTV applications for preventing

frequent usability problems.

Focused on the users’ aspects, Rice and Alm

(2008) proposed methodologies and interactive

practices influenced by the Participatory Design

(PD) to design solutions for supporting elderly

people to interact with iDTV. Bernhaupt et al.

(2010), in turn, used the Cultural Probes Method to

conduct ethnographic studies in order to understand

users’ media behavior and expectations, indicating

trends concerned with personalization, privacy,

security and communication.

Focusing on the broadcaster company’s aspects,

some works have adapted traditional methodologies

for software development (Gawlinski, 2003) and

Agile Methods (Veiga, 2006) to the companies’

production chain. The adapted methodologies

encompass the entire software development process

(e.g., requirement analysis, project, implementation,

testing and support); although robust in terms of the

technical process of software development, end

users are usually not considered in the process.

For TV broadcaster companies, the design of

interactive applications is a new component into

their production chains. Veiga (2006) argues that

designing iDTV applications is hardly supported by

existing methodologies (e.g., Cascade Model)

because it is different from designing traditional

software systems (e.g., desktop, web). Furthermore,

Kunert (2009) highlights that every emergent

technology suffers from a lack of references,

processes and artifacts for supporting their design.

Therefore, new simple techniques and artifacts that

fit broadcasters’ production chain and explore the

challenge of designing applications within the

broadcasters’ context are welcome.

Shedding light on this scenario, we draw on

Socially Aware Computing (Baranauskas, 2009),

Organizational Semiotics theory (Liu, 2000),

Participatory Design (Müller et al., 1997), and

Design Patterns for iDTV applications (Kunert,

2009) to propose three situated and participatory

practices for supporting designers to create and

evaluate iDTV applications: i) the Participatory

Pattern Cards; ii) the Pattern-guided Braindrawing;

and iii) the Participatory Situated Evaluation.

In this paper, we present the three practices and

the theories underlying them, and discuss the results

obtained from their usage in the practical context of

a Brazilian broadcasting company. The practices

were planned to facilitate the participation of

professionals from the TV domain that are not

familiar with iDTV applications design. A group of

9 persons, with different profiles, participated in

design workshops for creating an iDTV application

for one of the company’s programs. The results

suggest both the practices’ usefulness for supporting

design activities and the benefits of situated and

participatory design for iDTV applications,

indicating the viability of conducting the practices in

industrial settings.

The paper is organized as follows: the Section 2

introduces the theories and methodologies that

ground our work. Section 3 describes the new

practices created for supporting a situated and

participatory design of iDTV applications. Section 4

presents the case study in which the techniques were

applied, and Section 5 presents and discusses the

findings from the case study analysis. Finally,

Section 6 presents our final considerations and

directions for future research.

2 THEORETICAL AND

METHODOLOGICAL

FOUNDATION

Organizational Semiotics (OS) and Participatory

Design (PD) are two disciplines which represent the

philosophical basis for the design approach

considered in this work. Design patterns for iDTV

add to this theoretical basis contributing to shaping

the design product.

OS proposes a comprehensive study of

organizations at different levels of formalization

(informal, formal, and technical), and their

interdependencies. OS understands that all organized

behavior is effected through the communication and

interpretation of signs by people, individually and in

groups (Stamper et al., 2000; Liu, 2000). In this

sense, the OS supports the understanding of the

context in which the technical system is/will be

inserted and the main forces that direct or indirectly

act on it. If an information system is to be built for

an organization, the understanding of organizational

functions from the informal to the technical level is

essential (Liu, 2000).

The PD, originated in the 70’s in Norway, had

the goal of giving to workers the rights to participate

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

15

in design decisions regarding the use of new

technologies in the workplace (Müller et al., 1997).

In this sense, PD proposes conditions for user

participation during the design process of software

systems. PD makes use of simple practices that use

fewer resources (e.g., pen and paper), and considers

that everyone involved in a design situation is

capable of contributing, regardless of his/her role,

hierarchical level, and socio-economic conditions.

Two examples of participatory practices are

Brainwriting (VanGundy, 1983) and Braindrawing

(Müller et al., 1997). Both practices are examples of

cyclical brainstorming conducted to generate ideas

and perspectives from various participants for the

system to be built. While Brainwriting was created

to generate ideas for system features, Braindrawing

was proposed for generating graphical ideas for the

User Interface (UI).

Drawing on OS and PD, the Socially Aware

Computing (SAC) proposes to understand the design

cycle by working on the informal, formal and

technical issues in a systematic way; moreover, it

recognizes the value of participatory practices to

understand the situated character of design.

2.1 Socially Aware Computing

The Socially Aware Computing (SAC) is a socially

motivated approach to design (Baranauskas, 2009)

that supports the understanding of the organization,

the solution to be designed, and the context in which

the solution will be inserted, so that it can effectively

meet the sociotechnical needs of a particular group

or organization.

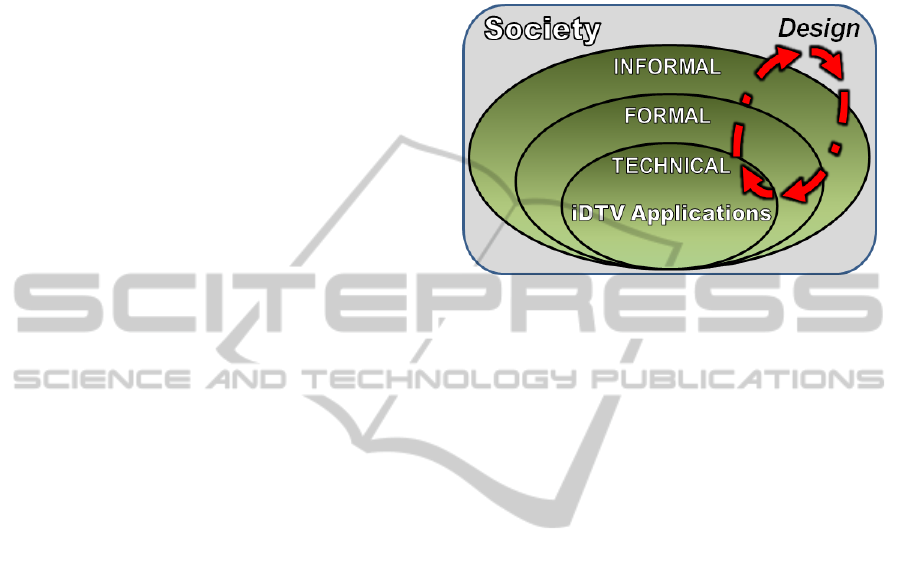

Considering the Semiotic Onion (Figure 1), SAC

understands design as a process that must go through

the informal, formal and technical layers cyclically

— see the dashed cycle. According to Baranauskas

(2009), the design process should be understood as a

movement that starts in the society (outside of the

semiotic onion) and progresses through the informal

and formal layers in order to build the technical

system. Once (an increment of) the technical system

is projected, the movement returns impacting on

formal and informal layers alike, including the

people for whom the system was designed, the

environment in which it is/will be inserted, and the

society in general. SAC is an iterative and

incremental process. Therefore, each iteration favors

the problem clarification, knowledge-building, and

the design and evaluation of the proposed solution.

For understanding the organization’s situational

context and the system inside it, SAC uses concepts

and techniques inspired by PD and OS. More than

the end user, SAC considers and involves key

stakeholders and heterogeneous groups of people

who may influence and/or may be influenced by the

problem being discussed and/or the solution to be

designed.

Figure 1: SAC’s meta-model for design.

The practices conducted in SAC are held throughout

the design process within Semio-participatory

Workshops (SpW). According to Baranauskas

(2013), each SpW has well-defined goals and rules

within the design process, such as: i) socialization

and personal introductions of the participants. ii)

explanations about the SpW to be conducted, its

concepts and objectives. iii) the role of the SpW in a

whole design process (in the cases where there are

more than one SpW to be conducted). iv) a well-

defined schedule for activities. v) artifacts and

methods created/adapted to be articulated with the

practices, and so on.

SAC has been used to support design in several

different contexts, being applied in design scenarios

of high diversity of users (e.g., skills, knowledge,

age, gender, special needs, literacy, intentions,

values, beliefs) and to create different design

products in both academic and industrial

environments (Pereira, 2013). Specifically for the

iDTV context, SAC has being used to support the

consideration of stakeholders’ values and culture

during the design process (Pereira et al., 2012), for

proposing requirements and recommendations to

iDTV applications (Piccolo et al., 2007), and to

physical interaction devices (Miranda et al., 2010).

2.2 Design Patterns for iDTV

Design patterns were originally proposed to capture

the essence of successful solutions to recurring

problems of architectural projects in a given context

(Alexander, 1979). In addition to their use in the

original field of architecture, design patterns have

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

16

been used in other fields, such as Software

Engineering (Gamma et al., 1995) and Human-

Computer Interaction (HCI) (Borchers, 2001), as

well as within different contexts, such as Ubiquitous

Computing (Chung et al., 2004) and iDTV (Kunert,

2009).

For new technologies, Kunert (2009) and Chung

et al. (2004) argue that design patterns present

advantages: i) they are distributed within a

hierarchical structure, which makes it easier to

locate and differentiate between patterns of different

granularity; ii) they are proposed in a simple

language; and iii) they incorporate references that

may indicate other forms of design guidance.

In the iDTV field, few studies proposing HCI

patterns are found in literature. For instance, Sousa

et al. (2006) previously identified a list of usability

patterns for specific interactive iDTV tasks, and

Kunert (2009) proposed a pattern collection that

focuses on interaction design for iDTV applications,

paying special attention to usability issues.

The pattern collection used in this work is the

one proposed by Kunert (2009). The patterns are

divided into 10 groups: Group A: Page Layout —

Defines the layout types to be used in the

application; Group B: Navigation — Defines what

types of navigation are to be used in the application;

Group C: Remote Control Keys — Defines the

main keys of the remote control; Group D: Basic

Functions — Highlights the basic functions that

should be considered in the design of interaction;

Group E: Content Presentation — Determines the

basic elements that form an application; Group F:

User Participation — Describes the interaction of

specific tasks; and the way how the approval for

connectivity should be handled; Group G: Text

Input — Defines the multiple ways to input text,

when to use each, and how to use them in an

application; Group H: Help — Defines the types of

help and how to provide them for users in an

appropriate way, according to the context of use;

Group I: Accessibility & Personalization — Deals

with accessibility and personalization issues; and

Group J: Specific User Groups — Illustrates

patterns for specific user groups (e.g., children).

Each of the 10 groups describes and illustrates first-

level problems that are divided into new design

problems of second and third levels. On the second

level, there are 35 interaction problems; for each

one, there is a corresponding pattern.

A pattern must follow a structure that is inherent

to the purpose of the language or to the set of

patterns on which it is inserted (Borchers, 2001).

Kunert’s iDTV patterns are characterized by: 1.

Reference: a unique identifier in the pattern

collection; 2. Name: usually describes the effect of

using the pattern (e.g., “Full-Screen without

Video”); 3. Examples: forms to use the pattern (e.g.,

images that illustrate the pattern being used); 4.

Context: an introductory paragraph contextualizing

the use of the pattern; 5. Problem: shows the forces

involved in the use of the pattern, aspects to be

considered, etc. 6. Solution: different and generic

ways of solving the problem; 7. Evidence:

references and usability tests used to demonstrate the

viability of the proposed solutions; 8. Related

Patterns: patterns that influence and/or are

influenced by the pattern in question.

There is not a strict order when choosing

patterns, however, Kunert (2009) suggests choosing

the layout and navigation patterns before the other

patterns, because this initial decision directly

influences the remaining ones.

3 THE PROPOSED

PARTICIPATORY PRACTICES

Drawing on the design patterns and the participatory

design techniques, we proposed three practices for

supporting design activities in a situated context: i)

Participatory Pattern Cards; ii) Pattern-guided

Braindrawing; and iii) Participatory Situated

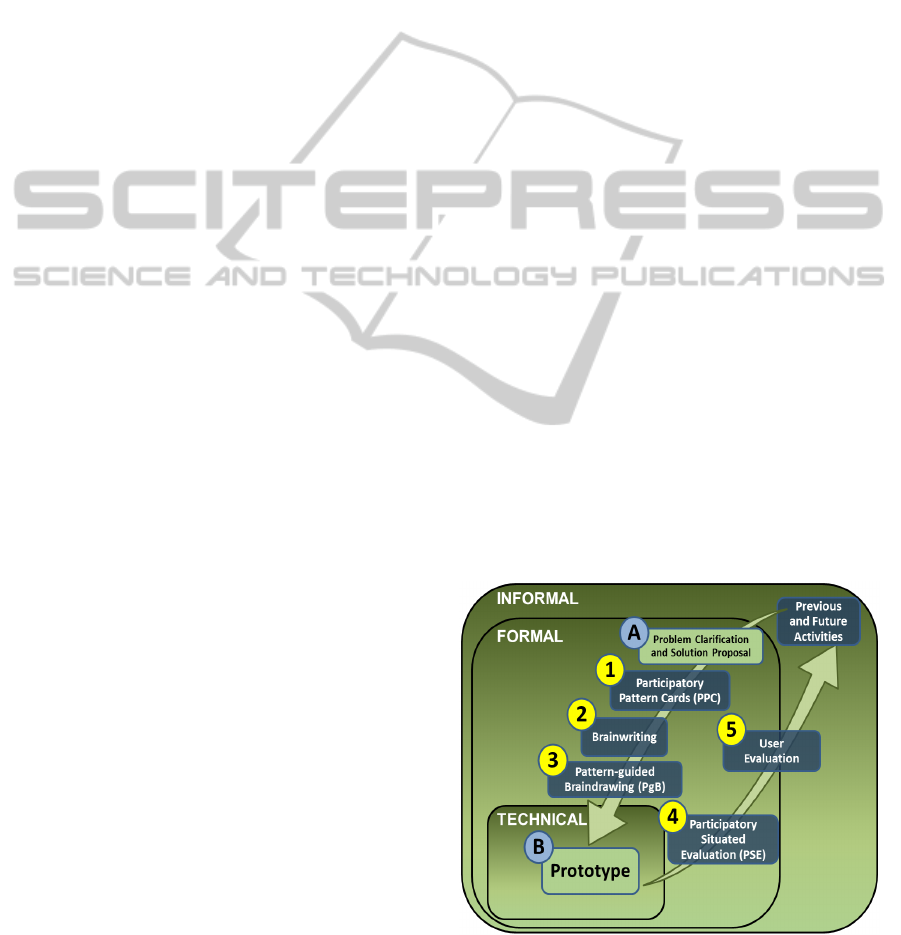

Evaluation. These practices were articulated with

other design activities in an instantiation of

Baranauskas’ SAC design process (2009) in order to

favor the situated and participatory design of iDTV

applications — see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Design process.

The “A” detail in Figure 2 suggests that the

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

17

problem domain must be clarified and a solution

proposal must be discussed in a participatory way

before engaging in further design activities. When

the problem is clarified and a solution is proposed,

three participatory practices (“1”, “2” and “3”

details) support the production of the first version of

the prototype (“B” detail); one participatory practice

supports the inspection of the designed prototype

(“4” detail), and one extra evaluation may be

conducted with prospective end-users (“5” detail).

These activities contribute to build and evaluate a

prototype for the application, offering useful

information for further iterations of the process (e.g.,

the codification stage, the design of new

functionalities, redesign).

The Participatory Pattern Cards (PPC) (“1”

detail in Figure 2) was conceived to support

discussions about design patterns for the iDTV, and

the identification and selection of the patterns

suitable for the application being designed. For this

practice, we created 34 cards based on Kunert’s

(2009) Design Patterns for the iDTV. Table 1

presents a description for the practice.

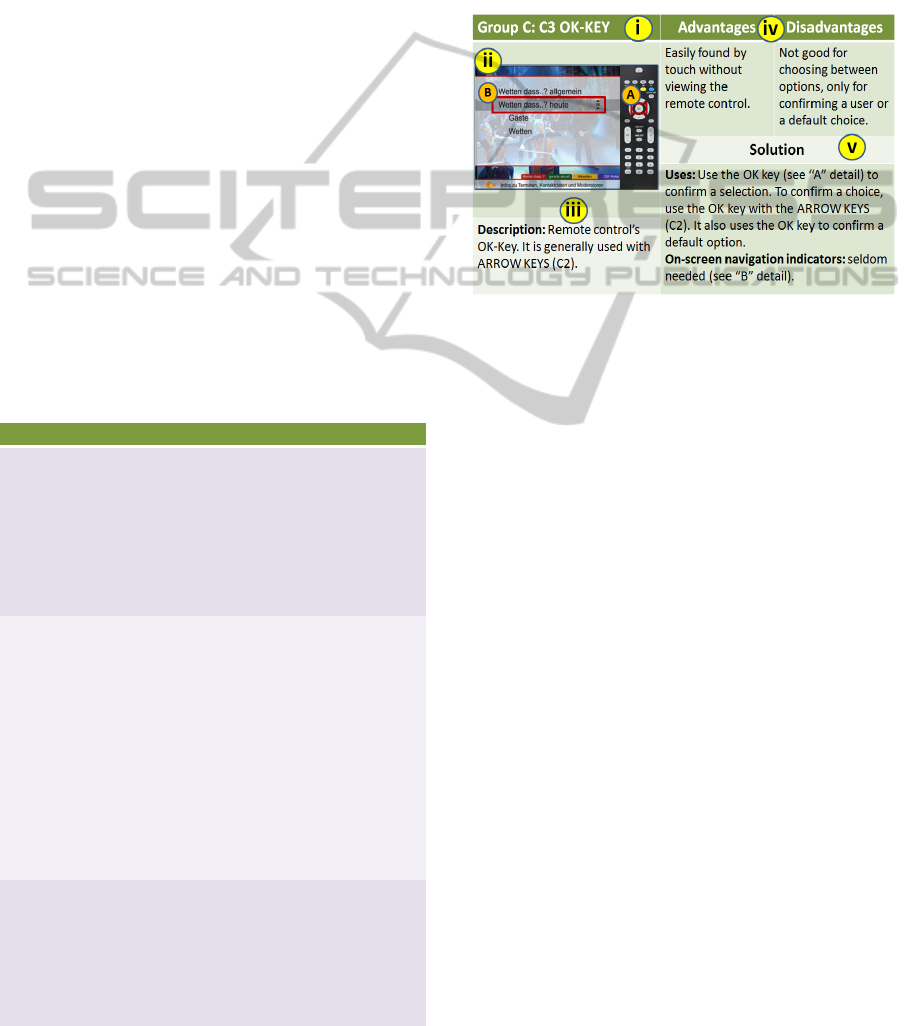

Figure 3 illustrates an example of a Pattern Card

created for the practice. Each card has the following

sections: i) group, reference and name of the pattern,

Table 1: Description of the PPC practice.

Participatory Pattern Cards (PPC)

Materials (input)

1. A set of 34 cards representing Kunert’s collection of

patterns: the cards are organized in 5 predefined

groups (e.g., patterns for the application’s layout;

patterns for the text input mode);

2. All the material produced in previous activities (e.g.,

a brief description of the design problem, a general

description of a solution proposal, a list of

requirements).

Methodology

1. Cards overview: participants are introduced to the

Pattern Cards, their different types and usage

examples;

2. Selection of patterns: for each card group,

participants should individually select the cards that

would potentially be used in the application.

3. Consensus: a brainstorming section where the

participants present the selected patterns and discuss

the pros and cons of each one in order to decide the

ones they will adopt;

4. Justification for the choices: once a consensus was

reached, participants must justify their choices based

on the project’s scope and requirements.

Results (output)

1. A subset of patterns that will potentially be used for

the application.

As byproducts, the practice: i) brings participants closer

to the iDTV domain; ii) draws attention to the limited

resources and technology that will be provided for the

system to be designed; and iii) may inspire design ideas

for future projects.

ii) an example of the pattern being used in a

given situation; iii) a brief description of the

problem; iv) forces (advantages and disadvantages)

that act directly and indirectly on the problem to be

solved; and v) the solution to the problem.

The PPC practice is useful to clarify the

constraints and potentials of iDTV technology and to

choose design patterns in a participatory way,

contributing to the construction of a shared

knowledge among the participants.

Figure 3: Example of a Pattern Card created from Kunert’s

(2009) collection of patterns.

The Brainwriting (“2” detail in Figure 2) is a silent

and written generation of ideas by a group in which

participants are asked to write ideas on a paper sheet

during a pre-defined time (e.g., 60 seconds). Once

this time was elapsed, each participant gives his/her

paper sheet with ideas to other participant and

receives another paper sheet to continue the ideas

written on it. This process is repeated several times

until a predefined criterion is satisfied — e.g., the

fixed time has run out; each paper sheet passed by

all the participants (Wilson, 2013). On the one hand,

Brainwritting is a good method for producing

different ideas in a parallel way, allowing the

participation of all without inhibition from other

participants. On the other hand, it focuses on the

question/problem being discussed rather than on the

person discussing it (VanGundy, 1983), avoiding

conflicts between the participants.

The Pattern-guided Braindrawing (PgB) (“3”

detail in Figure 2) is an adapted version of

Braindrawing that aims to generate ideas for the UI

of the application being designed, taking into

account the Design Patterns for iDTV. Table 2

presents a description for the technique.

The PgB allies the benefits from PD and Design

Patterns, being useful to materialize the ideas and

proposals produced in the previous steps into

prototypes for the application. Therefore, while the

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

18

participatory nature of both PPC and PgB techniques

motivates participants to generate design ideas that

rely on the perspectives of different stakeholders, the

use of Design Patterns informs these ideas and

guides their materialization.

Table 2: Description of the PgB practice.

Pattern-guided Braindrawing (PgB)

Materials

(input)

Paper sheets for drawing, colored pens, chronometer.

Methodology

1. Situating: participants are arranged in a circle; the

design problem and the results from the previous

activities (e.g., requirements, PPC) are briefly

reviewed;

2. Generation of design elements: keeping visible the

design patterns selected in the PPC and a list of

requirements for the application, participants start

drawing the application’s interface on a paper

sheet. After a pre-defined time (e.g., 60 seconds),

participants stop drawing, move the paper sheet to

the colleague seated on their right side, and receive

a paper sheet from a colleague seated on their left

side, continuing to draw on the received paper

sheet. This step repeats until all participants

contributed with ideas to all the paper sheets at last

once, i.e., a complete cycle;

3. Synthesis of design elements: From their own

paper sheets (the ones the participants initiated the

drawing), participants highlight the design

elements that appeared in their draws and that they

find relevant for the application.

4. Consensus: Based on the highlighted design

elements from each paper sheet, the group

synthesizes the ideas and consolidates a final

proposal that may include elements from all the

participants;

Results (output)

1. Different UI proposals that were created in the

participatory activity: each proposal presents

elements drawn by different participants, differing

from each other because they were started by a

different person;

2. A collaborative proposal for the application’s UI,

guided by design patterns, and created from the

consolidation of the different proposals by the

participants.

A picture of a television device and a screenshot of

the TV program may be used as background of the

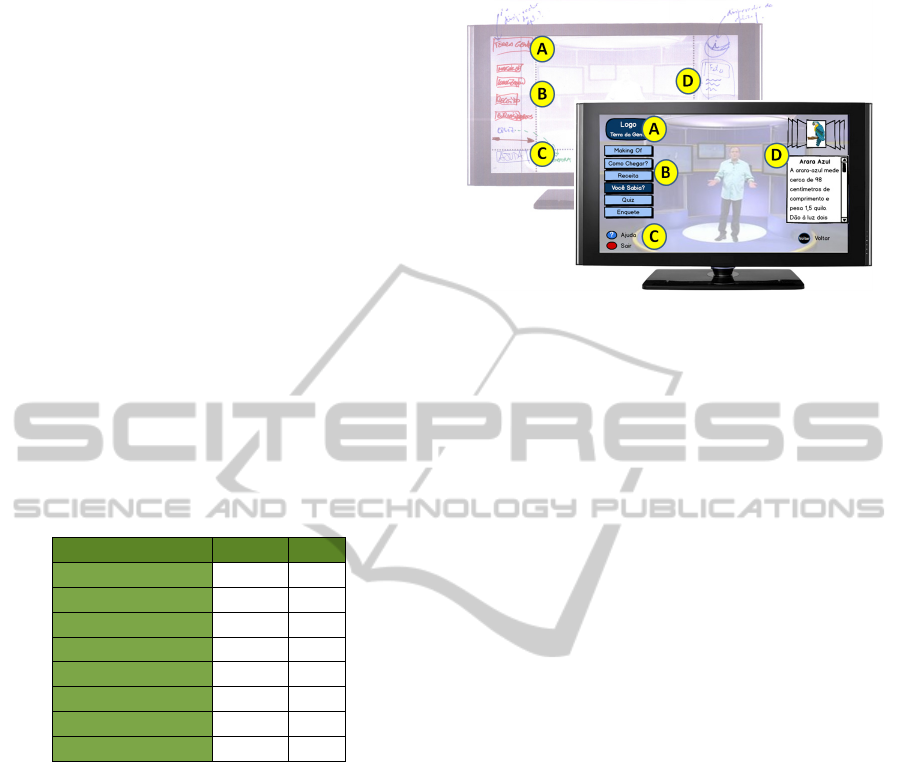

Figure 4: Example of a template for the PgB.

paper sheets used in PgB — as illustrated in Figure

4. This contributes to bring reality to the participants

during the activity, situating them according to the

device’s physical limitations, the program layout and

content.

The third practice created was the Participatory

Situated Evaluation (PSE) (“4” detail in Figure 2).

The PSE is an adapted version of Thinking Aloud

method (Lewis, 1982) that aims to bring together all

participants for the evaluation of an iterative

application — Table 3 presents a description for the

practice. This practice is useful to promote a

collective analysis and discussion about the

produced prototype; to identify shared doubts and

difficulties, as well as ideas for improving the

application. It avoids the prevalence of individual

opinions, favoring the collective discussion and

making sense about the application being evaluated,

and optimizing the time spent by the participants

during the activity.

Table 3: Description of the PSE practice.

Participatory Situated Evaluation (PSE)

Materials

(input)

Laptop, interactive prototype, video camera, and

software to record users interacting with the

prototypes.

Methodology

1. Situating: participants are arranged in a circle; the

interactive prototype is introduced to the

participants and the evaluation activity is

explained; participants can either conduct pre-

defined tasks (e.g., voting in a pool) or explore the

application in a free way;

2. Interacting with the prototype: a participant is

invited to interact with the prototype; using the

Thinking Aloud method (Lewis, 1982), the

participant speaks aloud for the group while

interacts with the prototype, reporting his/her

thoughts (e.g., general impressions about the

prototype, intentions, goals, difficulties, questions,

reasoning). The other participants can talk to each

other and to the person who is interacting with the

prototype, speaking their thoughts alike.

3. Consensus: based on the doubts, ideas, feelings and

difficulties found during the activity, the

participants elaborate a list of problems and

suggestions for improving the application.

Results

(output)

1. A mapping of the interaction and interface

problems identified through the activity;

2. Suggestions of improvements presented in the

group’s suggestion list.

User Evaluation (“5” detail in Figure 2) proposal:

the Thinking Aloud technique (Lewis, 1982) can be

used to capture users’ impressions and opinions. The

participants’ interaction, voices and facial

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

19

expressions can be recorded, and participants may

be invited to answer an evaluation questionnaire,

providing their overall impressions about the

prototype. The activity and data usage should be

conducted in accordance to ethical principles in

academic research.

4 THE CASE STUDY

The case study was conducted in a real context of a

television broadcasting company, named EPTV

(Portuguese acronym for “Pioneer Broadcasting

Television Stations”). EPTV is affiliate of a large

Brazilian broadcasting company. Currently, EPTV

programming reaches more than 10 million citizens

living in a microregion of about 300 cities (EPTV,

2014).

“Terra da Gente” (TdG, “Our Land”, in English)

is one of several programs produced by EPTV. The

program explores local diversity in flora and fauna,

cooking, traditional music, and sport fishing.

Currently, the program runs weekly and is structured

in 4 blocks of 8 to 10 minutes each. It counts on a

team of editors, writers, producers, designers,

technicians, engineers and journalists, among other

staff members. In addition to the television program,

the TdG team also produces a printed magazine and

maintains a web portal. Both the magazine and the

web portal serve as complementary sources of

material for the TdG audience (TdG, 2014).

The activities reported in this paper were

conducted from January to July, 2013, and involved

3 researchers from Computer Science and 6

participants playing different roles at EPTV:

TdG Chief Editor: is the person who coordinates

the production team (e.g., editors, content

producers, journalists, designers, etc.) of the

television program and the web portal.

Designer: is the responsible for the graphic art of

the television program as well as of the web

portal, and who will be responsible for the graphic

art of the iDTV application.

Operational and Technological Development

Manager: is the person who coordinates the

department of new technologies for content

production.

Supervisor of Development and Projects: is the

person who coordinates the staff in the

identification and implementation of new

technologies for content production and

transmission.

Engineer on Technological and Operational

Development: is the engineer of infrastructure,

and content production and distribution.

Technical on Technological and Operational

Development: is the person responsible for the

implementation, support and maintenance of

production systems and content distribution.

Researchers (3 people): are researchers in

Human-Computer Interaction and the responsible

for preparing and conducting the workshops. One

of them is expert in the SAC approach and other is

an expert in iDTV technologies.

All the participants, except for the researchers,

work in the television industry. The participants (P1,

P2...P9) collaborated in the workshops proposed to

the problem clarification, problem solving,

requirement prospecting, as well as the creation of

prototypes for the application and their evaluation,

within a SAC approach.

Regarding the familiarity of participants with

iDTV applications, from the 9 participants, 2 are

experts; 2 are users of applications; 5 participants

had already used/seen iDTV applications. Regarding

the frequency which the participants watch the TdG

program, 5 participants have been watching the TdG

program, but not very often: 1 participant watches

the program every week, 1 participant watches the

program in average twice a month, and 2

participants watch at least once a month.

4.1 Designing an Application for TDG

This section presents the main activities conducted

to create the first prototype of an iDTV application

for the TdG program. Before these activities,

participants had collaborated for the problem

understanding, and for the clarification, analysis and

organization of requirements for the application to

be designed — as proposed by the SAC approach,

and that are out of scope of this paper (“A” detail in

Figure 2). The materials produced by the previous

activities were used as input for the design activities

presented in this paper, and were reported in

(Buchdid et al., 2014).

Before the beginning of each activity, the results

obtained from the previous activities were presented

and discussed in a summarized way, and the

techniques to be used, as well as their methodologies

and purposes were introduced to the participants.

For instance, before the PPC activity, examples of

different existing iDTV applications, and the

patterns from Kunert (2009), were briefly presented

and discussed with the participants.

The PPC activity was the first participatory

practice conducted to design the application

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

20

prototype (“1” detail in Figure 2). Its input were the

documentation produced in the problem clarification

activities, the participant’s knowledge about the

project, and Pattern Cards based on the Kunert’s

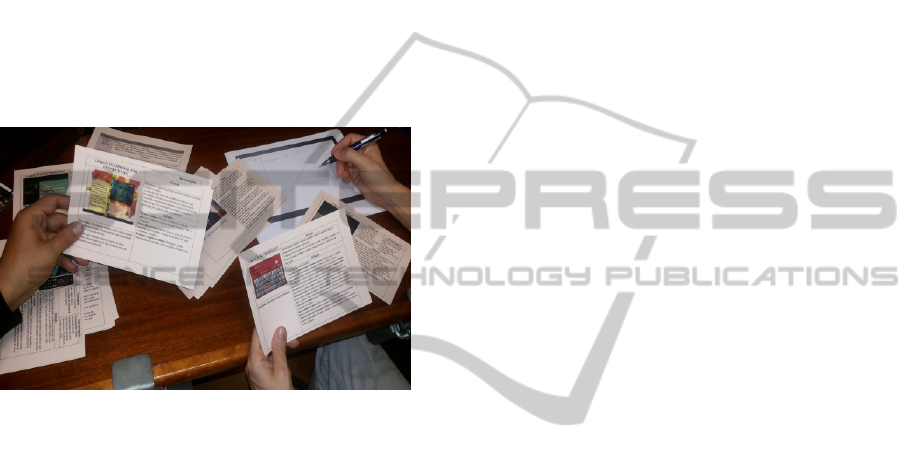

patterns (2009) — see Figure 5.

Originally classified into 10 different categories

(from “A” to “J”), the patterns were grouped into 5

major groups in order to facilitate the participants’

understanding: 1. Layout (Group A); 2. Navigation

(Group B); 3. Operation (Groups C, D and G); 4.

Content presentation (Groups E and F); and 5. Help,

accessibility and personalization (Groups H and I).

Patterns such as “B3 Video Multi-Screen” and “J1

Children” were not considered because they were

out of the projects’ scope.

Figure 5: Participants holding Pattern Cards.

The dynamic for this practice followed the

description presented in Table 1. While each group

of pattern was presented and discussed, participants

were asked to select the ones that would potentially

be used in the application. This practice lasted 90

minutes and was important to generate discussion

and ideas to the application; they also led to a shared

knowledge about iDTV potentialities and limitations

among the participants.

Guided by the discussions and the results

identified in the PPC practice, the Brainwriting

(“2” detail in Figure 2) was used to identify what the

participants wanted in the application and what they

thought the application should have/be. The dynamic

for this activity is similar to the PgB presented in

Table 2: each participant received a paper sheet with

the following sentence: “I would like that the “Terra

da Gente” application had...”; the participants should

write their initial ideas and, after a pre-defined time

(e.g., 60 seconds), they should exchange the paper

sheets and continue to write on the ideas initiated by

the other participants. After each paper sheet had

passed by all the participants and returned to the one

who started writing the idea, participants should

highlight the concepts that appeared in their paper

sheet, and expose them to the group for discussion.

The group reached a consensus creating a list of the

main functionalities that should appear in

application. This activity took 90 minutes.

The PgB practice was conducted based on the

ideas generated during the Brainwriting and took

into account the patterns selected in the PPC (see

“3” detail in Figure 2). The dynamic for this activity

is presented in Table 2: each participant received a

template in a paper sheet (see Figure 4), and they

were asked to explore the initial call for the

application, the layout and other specific content that

they would like to see in the application. Participants

started drawing the application interface, exchanging

their paper sheets periodically and continuing to

draw on the paper sheets of the other participants

until they received their paper sheet back. This

activity generated several ideas for the iDTV

application that were consolidated by the team in a

final proposal. This activity lasted 30 minutes.

Based on the results obtained from these

activities, the first prototype for the application was

built (“B” detail in Figure 2) by a researcher who

has experience in the development of iDTV

applications. The Balsamiq

®

tool was used to create

the UI and the CogTool

®

was used to model the

tasks and to create an interactive prototype. The

Pattern Cards were used again in order to inspect

whether the application was in accordance with the

design patterns, guiding the layout definition (e.g.,

font, elements size and position, visual arrangement

of these elements) and interaction mechanisms (e.g.,

remote control’s keys that were used).

The PSE was conducted in order to evaluate the

produced prototype — “4” detail in Figure 2. The

activity was conducted according to the structure

presented in Table 3. The interactive prototype was

presented to the participants, and one of them

explored the application using the “Thinking Aloud”

technique. The other participants observed the

interaction, took notes, and were able to ask, suggest

and discuss with the evaluator at any time. Both the

user interaction and the group dynamic were

recorded, providing interesting information about

the general perception of the participants and

possible features to be redesigned before

programming the final application. This practice

lasted 50 minutes and, after concluded, participants

answered a questionnaire evaluating the prototype.

Finally, a User Evaluation was conducted in

order to evaluate the prototype with prospective

representatives from the target audience that did not

participate in design activities — “5” detail in Figure

2. This activity was important to serve as a

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

21

parameter to the PSE evaluation, assessing whether

the prototype made sense to a more diverse

audience. For this activity, 10 participants explored

the prototype: 3 participants are 21-30 years old, 5

are 31-40 years old, 1 is 41-50 years old, and 1

participant is over 60 years old. Regarding their

formal education, from the 10 participants: 1 has

high school, 3 have bachelor’s degree, 1 has

specialization course, 3 have master’s degree and 1

participant has a doctor’s degree. None participant

had previous experience using iDTV applications; 8

participants were aware of them, but had never seen

any application; and 2 participants had seen them

before. Furthermore, from the 10 participants, 6

have been watching the TdG program, but not often;

3 participants watch once a month; and 1 participant

do not watch TdG.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section, we present and discuss the main

results from the practices we proposed in this paper

to create the interactive prototype for the TdG TV

program.

5.1 Results of Design Practices

During the PPC practice, the participants selected

20 patterns that could be used in the application

design. At least one pattern from each group of

patterns was considered by the participants.

Table 4 presents some of the patterns selected by the

Table 4: List of Patterns used in the activities.

Gro

u

p

s

Patterns PPC Explanation PgB

Operation

C3 Ok-key ✔

It must be the main method of

interaction together with arrow keys

✔

C4 Colour keys ✔

To be used in case of voting and

multiple-choice question

✔

C5 Number keys

Would not be used due to the

difficulty of use

C6 Special keys

Hard to find on remote control

✔

D1 Initial call to

action

✔

An unobtrusive call that does not

disturb who does not want to use the

application

✔

… ...

...

..

G3 Mobile phone

keyboard

✔

Must not occupy much space on the

screen. It will only be used in case of

text input

Help and cia

H1 On-Screen

instruction

It is not necessary because the

application is simple

✔

H2 Help section ✔

Help only in the Option menu

✔

I1 Accessibility ✔

Universal Design

I2 Personalisation

It is very sophisticated to this kind

of application

participants. The “Groups” column presents the

general group of the selected pattern; the “Patterns”

column presents the name of the pattern; the “PPC”

column indicates whether the pattern was selected

during the PPC practice; the “Explanation” column

explains the reason why the pattern was selected;

and the “PgB” column indicated whether the pattern

was identified in the prototype produced in the

Brain-Drawing practice.

For instance, the pattern “C3 Ok-key” was

selected to be “the main interaction method together

with arrow keys” in the PPC practice, and was

identified in the prototype produced in the PgB. The

pattern “C6 Special keys”, in turn, was not selected

in the PPC, but appeared in the prototype created by

the participants: It can be partially explained by the

fact that the participants got more used to the

patterns and may have perceived the need/benefits of

patterns they did not select during the PPC.

Therefore, this is both an indication that the PPC

does not narrow the participants’ views during the

creation of prototypes, and an evidence that the PgB

facilitates the revision of the selected patterns during

the creation of prototypes.

From the Brainwritting practice, 11 concepts

were created to be included in the application: 1.

Gallery/Making of: pictures from the TV program

and information about the backstage; 2.

Localization/Mapp: geographic coordinates of the

place in which the TV program was recorded;

additional information about roads, flights, trains,

etc. 3. Receipt/Ingredients: it presents the

ingredients of the receipt that will be prepared

during the TV program. 4. Information/Curiosity:

offers information and curiosities about the fauna

and flora existing in the place where the TV program

was recorded. 5. Evaluation Pool: a pool that allows

users to answer whether they liked the program they

are watching. 6. Quiz: a question-answer based-

game about subjects directly related to the TV

program content. 7. Fishing Game: a ludic game

intended to keep users’ attention through a virtual

fishing while they watch the TV program (e.g., a

little fish will appear on the screen and the user must

select a different key to fish it). 8. Fisherman Story:

a specific Quiz that allow users to answer whether a

given story is true or false. 9. Abstract: a summary

of the current TV program. 10. Prospection Pool: a

pool that allows users to vote in the subjected that

will be presented in the next program. 11. Chat:

asynchronous communication on the TV program.

The first 6 concepts were selected to be used in

the PgB activity. In addition, the participants were

invited to explore ideas to application’s trigger

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

22

(Pattern: “DI Initial Call to Action”) in the same

activity. The other concepts were not considered

because they were similar to a selected concept (e.g.,

Fisherman Story is similar to the Quiz), because they

were considered uninteresting (e.g., Summary), or

because they would require high attention and

cognitive effort to be used (e.g., Chat).

All the six selected concepts appeared in the

individual prototypes created by the participants of

the PgB practice as well as in the final prototype

consolidated by the participants. For instance, the

“Gallery/Making of” concept appeared in 7

individual prototypes (see the column “Frequency”

in Table 5), and was represented in 4 different forms

(column “Forms”). The 9 individual prototypes also

represented the “Localization/Mapp” concept in 4

different forms. Furthermore, the “Fishing Game”

appeared 3 times even not being one of the chosen

concepts; indicating that the activity favored the

appearance of different and diverse ideas.

Table 5: List of concepts represented in the individual

prototypes.

Concept Frequency Forms

Gallery/Making Of 7 4

Localization/Mapp 9 4

Receipt/Ingredients 7 4

Information/Curiosities 7 4

Evaluation Pool 5 3

Quiz 5 3

Application’s Trigger 6 6

Fishing Game 3 3

The individual prototypes generated in the PgB were

consolidated into a final prototype that, in turn, was

used as the basis for creating an interactive

prototype for the TdG iDTV application. The six

concepts cited previously, as well as the patterns

presented in Table 4, and general ideas elaborated by

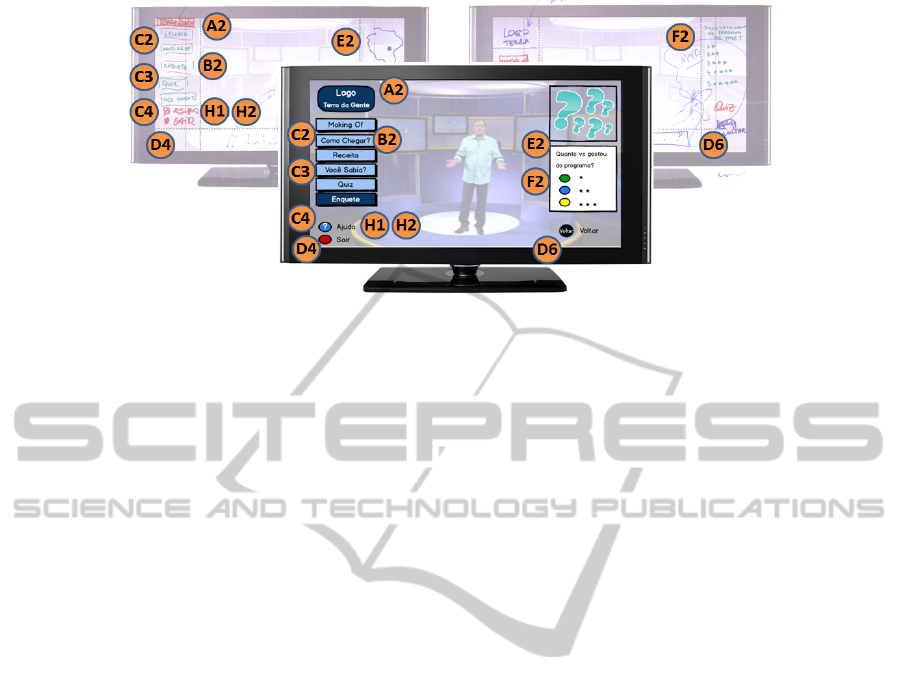

the participants were reflected in the interactive

prototype. The Figure 6 presents details indicating

attributes and components of the final prototype

produced by the participants that were reflected in

the interactive prototype created by the researchers.

For instance, the logo (“A” detail) and menu

position (“B” detail); the selected remote control

keys and their positions on screen (“C”); and the

content for each application section (“D”).

The design patterns selected in the PPC practice

were reflected in both the final prototype produced

by the participants and the interactive prototype

created by the researcher. For instance, the patterns

“C4 Colour keys” and “H2 Help section” were

selected in the PPC activity and were considered in

Figure 6: Example of attributes and components generated

through the PgB practice.

the individual prototypes — see Table 4, and were

also considered in the interactive prototype — see

details “C4” and “H2” in Figure 7.

5.2 Results of the Evaluation Practices

Both the PSE and the evaluation with prospective

representatives from the audience produced

suggestions for redesigning the interactive

prototype. For instance, during the PSE it was

identified that users could leave the application at

any moment/any level of interaction; however, the

evaluation indicated that it could cause interaction

problems, such as the user accidentally leaving the

application while trying to see a picture from the

backstage. The participants recommended disabling

the “Exit” functions when the user enters in a second

level menu/function. Furthermore, the “Help”

function also should be applied only to the general

application (not in specific sub-menus), because the

application is very easy to use and the button could

disturb the user in specific activities.

Other useful feedbacks were obtained from the

PSE practice, such as the suggestion to use numbers

in the pool’s options in order to facilitate the

selection, and not confuse users with other

application’s functions that use colors key; and the

recommendation to not deploy the “Quiz” and the

“Pool” features simultaneously in the application in

order to not overload users with similar features.

The participant who explored the interactive

prototype in the PSE practice was clearly pleased for

not having difficulties while using it, highlighting

the simplicity and consistency of the interactive

prototype. Using his words: “(…) if even me was

able to understand and use the prototype, then it

means the prototype is very intuitive.” [laughs] — he

had never used an iDTV application before.

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

23

Figure 7: Patterns highlighted on the mockups from the PgB and on the final prototype.

The participants’ responses to the evaluation

questionnaire also indicated a positive opinion about

the interactive prototype. From the 9 participants

who answered the questionnaire, 7 (78%) responded

they really liked the prototype, and 2 (22%)

answered that they liked moderately. No indifferent

or negative response was provided, indicating that

the prototype met the participants’ expectations.

The test with representatives from the audience

reinforced a favorable opinion about the interactive

prototype. The 10 prospective users were able to

understand and explore the prototype, indicating its

simplicity. From their responses to the evaluation

questionnaire, 5 users (50%) answered they really

liked the prototype, 4 users (40%) answered they

liked moderately, and 1 users (10%) answered with

indifference. Although we need to test the

application with a higher number of users in order to

have data with statistical relevance, obtaining 90%

of positive responses is a good indication given that

they did not participate in design activities and had

no prior contact with iDTV applications.

5.3 Discussion

During the participatory practices, the constructive

nature of the process allowed to see how different

viewpoints were conciliated, different proposals

were consolidated, a shared understanding about the

problem domain and the application was created,

and how the discussions were materialized into a

solution proposal. Ideas and concepts that were

discussed when the project started could be

perceived during the practices and were reflected in

the final prototype.

The interactive prototype reflected the results

from both PPC and PgB practices, allowing the

participants to interact with the prototype of the

application they co-created. The examples of

existing applications presented to the participants

were useful to illustrate different solutions regarding

the patterns, inspiring the design of the new

application and avoiding design decisions that would

not satisfy them. The PPC practice was especially

useful to: i) present the constraints, limitations and

challenges of designing for iDTV; and ii) introduce

participants to design patterns for iDTV, which may

support their design decisions.

The PgB, in turn, was useful for supporting a

pattern-guided construction of UI proposals for the

application from the material produced in the

previous activities. This practice is especially

important because it favored the consideration of

Design Patterns in the prototype design, and because

it allowed all the participants to expose their ideas

and to influence the prototype being designed,

avoiding the dominance of a single viewpoint. For

instance, the “Pool” and the “Quiz” were concepts

that emerged from the Brainwritting and were

materialized during the PgB practice, but were

strongly discussed among the participants because

some of them did not approve these features.

However, after listening pros and cons of

keeping/removing these concepts from the project’s

scope, the participants decided to keep both concepts

in the final prototype.

One of the most important points in this project

is its situated context. The conduction of

participatory practices in a situated context

contributed to understand different forces related to

the project and the organization in which it was

being conducted. In each new practice, it was

possible to clarify tensions between the participants,

the context in which the EPTV operates, the high

importance of the TdG program for EPTV

organization, the relation between the affiliate and

its headquarter and, mainly, the role that the

application may play in the TV program.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

24

Participants have different views and understandings

regarding the competition (for the user attention)

between the application and the TV program, and

different opinions about what the application should

offer to users and the way it should be offered. Such

complex context would be difficult to understand in

a non-situated design, and such conflicts would be

hard to deal with if participatory practices were not

part of the methodology.

Regarding the prototype evaluation, the PSE was

important to foment discussions on the design

decisions. Furthermore, the feedback from

prospective users was important to verify decisions

made with outsiders: people who did not participate

in the design process (e.g., how to present the recipe:

only the ingredients should be included? The

preparation mode should also be displayed?).

The practices reported in this paper demonstrate

that it is possible to conduct situated and

participatory design in industrial settings. There is

usually a myth that these practices are expensive and

difficult to be conducted. In fact, in less than 4 hours

a prototype was built from the documentation

produced in the previous practices and from the

discussion between the participants — including the

time spent to present examples of existing

applications and the lecture for presenting the

patterns. Some of the participants had a vague idea

about how to design iDTV applications and none of

them had designed this kind of application before.

Furthermore, the four workshops conducted at

EPTV took about 12 hours. It means that all the

process, from the problem clarification to the

prototype evaluation, took them less than two days

of work. It is clear that a great effort from the

researchers was needed in order to summarize,

analyze and prepare the practices as well as to

prepare the presentations and build the interactive

prototype. Indeed, this effort is expected because a

lot of work must be done in parallel to the practices

organization and conduction. Therefore, this

experience shows that it is possible, viable and

worth the time used to make participatory design in

a situated context.

The experience at EPTV also indicated that a

situated and participatory design contributes to the

development of solutions that are in accordance to

both the people directly involved in design practices

and the prospective end users of the designed

solution. On the one hand, the participatory

evaluation indicated that the participants approved

the interactive prototype they co-designed; it was

expected because of the participatory and situated

nature of the process conducted. On the other hand,

the evaluation with representatives from the target

audience reinforced the positive results, indicating

that the application was understood and well

accepted by users that were not present in design

activities and that had never experienced an iDTV

application before.

These results suggest that a situated and

participatory design perspective favors the

construction of solutions that make sense to people,

reflecting an understanding about the problem

domain and the complex social context in which

these solutions will be used.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Designing iDTV applications is a complex activity

due to several factors including the ecosystem of

media that compete and cooperate with the TV. In

addition, the production chains of the broadcasters

are still not prepared to the design of iDTV

applications. This paper proposed three different

practices and presented activities for supporting a

situated and participatory design of iDTV

applications; a case study situated in real scenario of

a TV organization illustrated the proposal in action.

The results obtained from the case study

indicated the benefits of using the practices for

supporting the involved parties to understand the

situated context that the iDTV application will be

inserted, and to design an application that reflects

that understanding. The results suggested that the

interactive prototype designed was widely accepted

by both the participants and prospective end users,

pointing out the situated and participatory process as

a viable and useful perspective for designing iDTV

applications.

Although the results so far are very positive, the

prototype still needs to be broadcasted as an iDTV

application in Terra da Gente TV show. Thus,

further work involves the next steps of implementing

and testing the final application and releasing it for

use by the TV program viewers. We also intend to

conduct further studies within the perspective of the

Socially Aware Computing, to investigate the

potential impact of the practices presented in this

paper to the TV staff and iDTV end users.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is partially funded by CNPq

(#165430/2013-3) and FAPESP (#2013/02821-1).

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

25

The authors specially thank the EPTV team by the

partnership, and the participants who collaborated

and authorized the use of the documentation of the

project in this paper.

REFERENCES

Alexander, C., 1979. The Timeless Way of Building.

Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1

st

edition.

Bannon, L., 2011. Reimagining HCI: Toward a More

Human-Centered Perspective. Interactions, 18(4), pp.

50-57.

Baranauskas, M. C. C., 2009. Socially Aware Computing.

In: ICECE 2009, VI International Conference on

Engineering and Computer Education, pp. 1-5.

Baranauskas, M. C. C., 2013. O Modelo Semio-

participativo de Design. In: Baranauskas, M.C.C.;

Martins, M.C.; Valente, J.A.. (Org.). Codesign De

Redes Digitais - Tecnologia e Educação a Serviço da

Inclusão. 103ed.: Penso, v. 1, pp. 38-66.

Buchdid, S. B., Pereira, R., Baranauskas, M.C.C., 2014.

Creating an iDTV Application from Inside a TV

Company: a Situated and Participatory Approach. In:

ICISO’14, 15th International Conference on

Informatics and Semiotics in Organisations. (in press).

Bernhaupt, R., Weiss, A., Pirker, M. Wilfinger, D.,

Tscheligi, T., 2010. Ethnographic Insights on Security,

Privacy, and Personalization Aspects of User

Interaction in Interactive TV. In: EuroiTV’10, 8th

international interactive conference on Interactive TV

and Video. ACM Press, New York, NY, pp. 187-196.

Borchers, J., 2001.A Pattern Approach to Interaction

Design. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, England.

Cesar, P., Chorianopoulos, K., Jensen, J.F., 2008. Social

Television and User Interaction. M. Computers in

Entertainment, vol.6, no.1, pp. 1-10.

Chorianopoulos, C., 2006. Interactive TV Design That

Blends Seamlessly with Everyday Life. In: ERCIM

’06, 9th conference on User interfaces for all.

Springer, Berlin, DEU, pp. 43-57.

Chung, E. S., Hong, J. I., Lin, J., Prabaker M. K., Landay,

J.A., Liu, A.L., 2004. Development and evaluation of

emerging design patterns for ubiquitous computing.

In: DIS’04, 5th Conference on Designing Interactive

Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and

Techniques. ACM Press, New York, pp. 233-242.

EPTV, EPTV Portal, 2014. Retrieved from:

http://www.viaeptv.com, on Jan 14.

Fallman, D., 2011. The New Good: Exploring the

Potential of Philosophy of Technology to Contribute

to Human-Computer Interaction. In: CHI’11, 2011

Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems. ACM Press, New York, pp. 1051–1060.

Gamma, E., Helm, R., Johnson, R., Vlissides, J., 1995.

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-

Oriented Software. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

Gawlinski, M., 2003. Interactive Television Production.

Oxford: Editora Focal Press.

Harrison, S., Tatar, D., Sengers, P., 2007. The three

paradigms of HCI. In Alt.CHI, 2007 Annual

Conference on Human Factors in Computing System.

ACM Press, New York, pp. 1-18.

Kunert, T., 2009. User-Centered Interaction Design

Patterns for Interactive Digital Television

Applications. Springer, New York, 1

st

edition.

Liu, K., 2000. Semiotics in Information Systems

Engineering. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

1

st

edition.

Lewis, C. H., 1982. Using the “Thinking Aloud” Method

In Cognitive Interface Design. IBM Research Report

RC-9265, Yorktown Heights, NY.

Miranda, L. C., Hornung, H., Baranauskas, M. C. C.,

2010. Adjustable interactive rings for iDTV. IEEE

Transactions on Consumer Electronics, 56, pp. 1988-

1996.

Müller, M. J., Haslwanter, J. H., Dayton, T., 1997.

Participatory Practices in the Software Lifecycle. In:

Helander, M.G., Landauer, T.K., Prabhu, P.V. (eds.).

Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, 2

nd

edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 255-297.

Pereira, R., 2013. Key Pedagogic Thinkers: Maria Cecília

Calani Baranauskas. Journal of Pedagogic

Development, UK, pp. 18-19.

Pereira, R., Buchdid, S. B., Baranauskas, M. C. C., 2012.

Keeping Values in Mind: Artifacts for a Value-

Oriented and Culturally Informed Design. In

ICEIS’12, 14th International Conference on

Enterprise Information Systems. SciTePress, Lisboa,

pp. 25-34.

Piccolo, L. S. G., Melo, A. M., Baranauskas, M. C. C.,

2007. Accessibility and Interactive TV: Design

Recommendations for the Brazilian Scenario. In:

INTERACT '07, 11th IFIP TC 13 International

Conference. Springer, Berlin, DEU, pp. 361-374.

Rice, M., Alm, N., 2008. Designing new interfaces for

digital interactive television usable by older adults.

Computers in Entertainment (CIE) - Social television

and user interaction, Vol. 6, No. 1, Article 6, pp. 1-20.

Sellen, A., Rogers, Y., Harper, R., Rodden, T., 2009.

Reflecting Human Values in the Digital Age.

Communications of the ACM, 52(3), pp. 58-66.

Solano, A.F., Chanchí, G.E., Collazos, C.A., Arciniegas, J.

L., Rusu, C. A., 2011. Diseñando Interfaces Graficas

Usables de Aplicaciones en Entornos de Televisión

Digital Interactiva. In: IHC+CLIHC '11, 10th

Brazilian Symposium on on Human Factors in

Computing Systems and the 5th Latin American

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. ACM

Press, New York, NY, pp. 366-375.

Sousa, K., Mendonça, H., Furtado, E., 2006. Applying a

multi-criteria approach for the selection of usability

patterns in the development of DTV applications. In:

IHC’06, 7th Brazilian symposium on Human factors in

computing systems, ACM Press, New York, pp. 91-

100.

Stamper, R., Liu, K., Hafkamp, M., & Ades, A., 2000.

Understanding the Roles of Signs and Norms in

Organisations: a semiotic approach to information

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

26

system design. Journal of Behaviour & Information

Technology. Vol 19(1). pp. 15-27.

TdG, Terra da Gente Portal, 2014. Retrieved from:

http://www.terradagente.com.br, on Feb 14.

VanGundy, A. B., 1983. Brainwriting For New Product

Ideas: An Alternative to Brainstorming. Journal of

Consumer Marketing, Vol. 1, Issue 2, pp. 67-74.

Veiga, E. G., 2006. Modelo de Processo de

Desenvolvimento de Programas para TV Digital e

Interativa. 141 f. Masters’ dissertation - Computer

Networks, University of Salvador.

Wilson, C., 2013. Brainstorming and Beyond: a User-

Centered Design Method. Elsevier Science,

Burlington, 1

st

edition.

Winograd, T., 1997. The design of interaction. In Beyond

Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing.

Copernicus. Springer-Verlag. pp.149-161.

PlayingCardsandDrawingwithPatterns-SituatedandParticipatoryPracticesforDesigningiDTVApplications

27