Fundamental Artificial Intelligence

Machine Performance in Practical Turing Tests

Huma Shah, Kevin Warwick, Ian M. Bland and Chris D. Chapman

School of Systems Engineering, The University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, U.K.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Imitation Game, Turing Test, Simultaneous Comparison Test, Viva Voce Test.

Abstract: Fundamental artificial intelligence is founded on Turing’s imitation game. This can be implemented in two

different ways: a simultaneous comparison 3-participant test, and a 2-participant viva voce test. In the

former, the human interrogator questions two hidden interlocutors in parallel deciding which is the human

and which is the machine. In the latter test, the judge interrogates one hidden entity and decides whether it is

a human or a machine. The results from an original experiment conducted at Bletchley Park in June 2012

implementing both tests side-by-side showed the simultaneous comparison was a stronger test for artificial

intelligence.

1 INTRODUCTION

Turing’s imitation game (Turing, 1950) can be

implemented in two formats. A 3-participant

simultaneous comparison test features a judge blind-

reviewing two hidden interlocutors in parallel – one

a machine the other a human (Shah, 2011; Shah,

2013). A viva voce version involves two

participants: a judge interrogating a machine (ibid).

As part of the Alan Turing Centenary Year

celebrations an original experiment was conducted

at Bletchley Park on the 100

th

anniversary of

Turing’s birth: 23 June 2012 (Warwick & Shah,

forthcoming). Both the simultaneous comparison

and the viva voce tests were staged side-by-side for

5-minute duration (Turing, 1950). A total of 180

tests were conducted: 120 simultaneous and 60 viva

voce set ups. Among these were 90 control tests

featuring 2machines, 2humans and a hidden human-

viva voce. In this paper we report on the 90 tests

involving one machine. The results showed when

the machine was interrogated in parallel with a

hidden human in a simultaneous comparison test it

had a tougher time deceiving a human judge. In this

case the judge’s attention is divided over the 5

minutes, whereas in the viva voce it is concentrated

on one interlocutor.

A further experiment is planned for June 2014 to

answer questions raised here. In the next section, we

trace the origins of Turing’s two tests and then detail

the experiment.

2 IMITATION GAME

The ideas for Turing’s imitation game flowed from

his work (see Turing, 1947, 1948, 1950 1951ab and

1952). It involves a human interrogator acting as

judge using typewritten interaction only to decide

whether he or she is interacting with a human or a

machine. The rules of Turing’s dramatic game

(Hodges, 2010) stipulate the judge must sit in a

separate room from the hidden interlocutors. This

was Turing’s sense of fair play to the machine [ibid],

so that the machine was not judged on beauty or

tone of voice (Turing, 1947).

Turing’s imitation game progressed from chess

to language (Shah, 2011; Shah, 2013). Turing

believed the learning of languages was one of the

most impressive and most human of a number of

activities (Turing, 1948). He felt the question-

answer method was “suitable for introducing almost

any one of the fields of human endeavour that we

wish to include” (Turing, 1950).

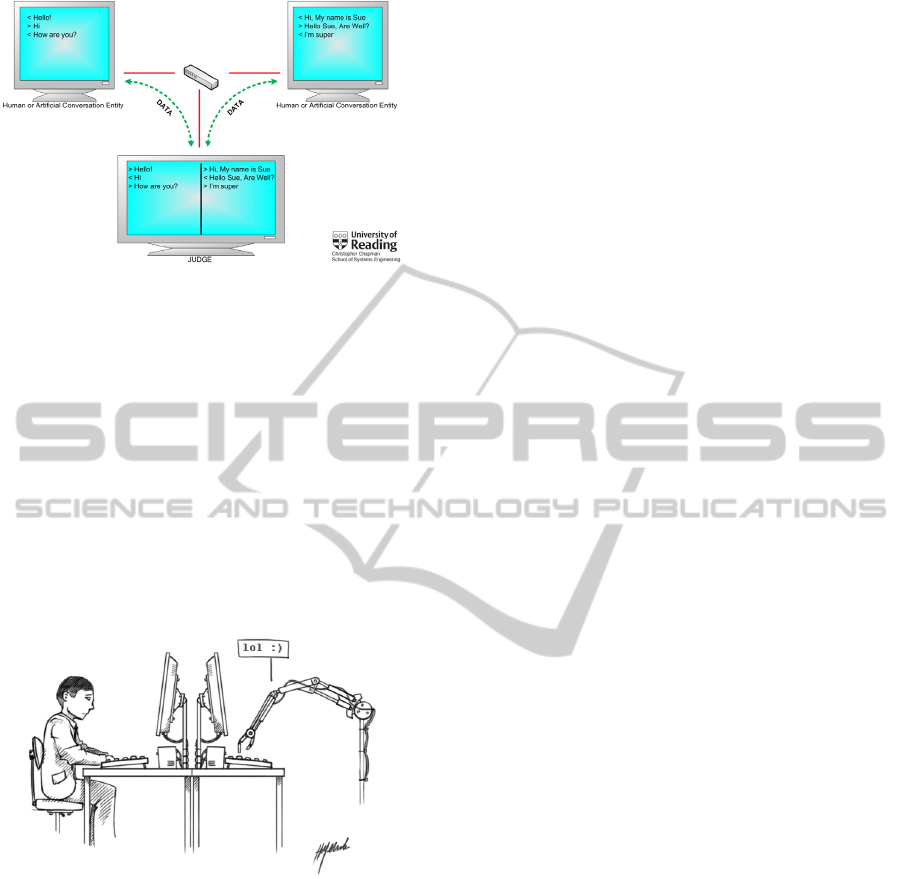

2.1 Simultaneous Comparison Test

Turing introduced the 3-participant interrogator-

machine-human test (see Figure 1) from the man-

woman game replacing one of the human

participants with a digital computer (Shah, 2011;

Shah, 2013).

559

Shah H., Warwick K., Bland I. and Chapman C..

Fundamental Artificial Intelligence - Machine Performance in Practical Turing Tests.

DOI: 10.5220/0004905905590564

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2014), pages 559-564

ISBN: 978-989-758-015-4

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Figure 1: Turing’s Simultaneous comparison test.

2.2 Viva Voce Test

In Turing’s 1950 Mind paper, in his rebuttal of The

Argument from Consciousness, Turing explicitly

imagines a viva voce scenario for his imitation game

(p. 445). This sees an interrogator directly

questioning a machine ‘witness’ one-to-one (see

Figure 2). Turing wrote, “accept the imitation game

as a test… the game (with the player B omitted) is

frequently used in practise under the name of viva

voce to discover whether some one really

understands something or has ‘learnt it parrot

fashion’ ” (1950).

Figure 2: Turing’s Viva Voce Test.

Until now no experiment had been performed

staging both scenarios to find which one was the

best to examine machine dialogue and the harder test

for the machine. The next section presents the

method and results from the experiment

implementing simultaneous comparison and viva

voce tests side-by-side.

3 MACHINE PERFORMANCE

We describe 90, of the 180 tests conducted in total

that involved at least one machine. The remaining 90

trials were control tests: 30 viva voce between

human interrogator and hidden human; and 60

simultaneous comparisons: 30 tests with 2human

and 30 with 2machine (see Warwick and Shah,

2013; Warwick and Shah, forthcoming).

The 90 tests reported here are 30 viva voce tests

examining a machine (see Figure 2). These were

embedded among 60 simultaneous comparison tests

involving a machine and a hidden human

comparator (see Figure 1). All tests were distributed

among five sessions spread across a whole day of

Imitation Games carried out on 23 June 2012.

3.1 Hypothesis

The simultaneous comparison is a tougher test for

the machine. This is because the human interrogator

has access to two responses in parallel and can

subjectively decide which is human.

3.2 Method

Six computer terminals were set up in the judge area

in the Billiard Room at Bletchley Park. This was the

public area; here the interrogator-judges sat

engaging the hidden interlocutors, who were located

in another room (see Warwick & Shah,

forthcoming). The judges’ terminals were connected

to another series of computer terminals hidden from

view and hearing in the Ballroom in Bletchley Park.

Five sessions were administered with each session

consisting of six rounds, a total of thirty tests in each

session. In each round there were two set ups of

human interrogator-machine with human foil

simultaneous comparison tests and one viva voce

interrogator-machine witness test. It is these three

tests in the 30 rounds of the experiment that we

focus on here.

3.2.1 Participants

Human participants came from members of the

public, journalists and experts in the field of

computer science and philosophy (Warwick and

Shah, 2013; Warwick and Shah, forthcoming). Elite

developers were invited based on their machine’s

performance in previous Turing tests (Shah and

Warwick, 2010ab). Thus, three types of participants

were involved in this experiment:

Human interrogators

Elite machines

Human comparators for the machines.

30 human interrogator judges, and 30 hidden entities

(5 elite machines and 25 human foils), each had a

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

560

unique experiment identity (e.g. J1, E1, E15).

Human interrogators and foils were made up of

teenagers and adults, males and females and people

who had English as their first or only language

(native) as well speakers of English as an additional

language (non-Native English speakers).

3.3 Procedure

Each human participant was given specific

information about their role: judges had to uncover

the machines and recognise humans. Hidden humans

were asked to ‘be themselves’ (Warwick and Shah,

forthcoming). There were asked not make it easy for

the machines by appearing machinelike (ibid). They

were given the following example of a machine

response in a practical Turing test (Chip Vivant,

2012):

I can’t deal with that syntactic variant yet.

The objective of the machines was to convince the

judges that they were human. Each judge and each

human foil participated in one session of six rounds

(Warwick and Shah, 2013; Warwick and Shah,

forthcoming).

Rounds timed to last 5 minutes were terminated

by disabling the graphic user interface via an

especially written communications protocol

(MATT). The protocol would perform an automatic

switch presenting the interrogator judge with the

next interlocutor(s) for the following round. This

was repeated until the session’s six rounds were

completed.

At the end of every round each interrogator

completed a paper score sheet giving their judgment

on the interlocutors(s). Judges’ feedback included:

Scoring a machine for conversational ability from

0-100, where 0=machinelike and 100=humanlike,

Assessment of human: male or female; adult,

teenager or a child; native English speaker or non-

native English speaker,

Score of ‘unsure’ was allowed. This was in the case

when the interrogator could not say whether they

had interacted with a human or a machine.

3.4 Results

As hypothesised, simultaneous comparison was the

stronger test for machines. However, it was also the

more difficult for the judges, because they had to

attend to two linguistic outputs in parallel to each

input. In the 30 viva voce tests, in which a machine

had twice as long (full 5 minutes) interaction time

with a judge, the machines collectively deceived a

human judge into attributing a human score at a rate

of 16.67%. If we include the two viva voce tests in

which a judge was unsure whether they were

speaking to a human or a machine, then the

inaccurate identification of machines in the viva

voce tests was 23.33% (see Table 1).

Table 1: Strength-comparison of Turing’s Two Tests.

Strength of

Turing’s two

tests

Turing’s Imitation Game

Viva voce

one-to-one

direct tests

Simultaneous

comparison

Machine-human tests

Number of

tests

30 60

Number of

deceptions

5 8

Total

inaccurate

classification

7

(twice machine

classified as

Unsure)

8

Type of error

Eliza effect

4 tests: both human

4 tests: machine

considered human &

human considered

machine

% inaccurate

classification

23.33% 13.33%

The results showed the simultaneous test, in which

the machine shared 5minutes interrogation time with

a human comparator, was almost twice as difficult

for a machine to achieve misclassification as human,

13.33% given half the time as in the viva voce test

(see Graph 1).

Graph 1: Machine deception rate in Turing’s Two Tests.

Judges were deceived at a rate of 13.33% in

simultaneous tests compared to 23.33% in viva voce

tests (Table 1; Graph 1). We present basic statistics

here, because the qualitative data enlightens more

about machine performance. Turing dismissed

statistical surveys with a comment on Gallup poll

(1950, p. 433); he preferred to examine whether a

machine could sustain satisfactory responses as a

significant performance measure. In the Discussion

section we present transcripts from five of the tests.

These highlight why the judges in the simultaneous

tests were less likely to be deceived: they instantly

FundamentalArtificialIntelligence-MachinePerformanceinPracticalTuringTests

561

had two responses to their question, assertion or

statement and could compare one with the other

deciding what was an artificial reaction from a

natural retor

t.

3.5 Discussion

Turing had noted the problem of subjectivity, writing

“It is conceivable that the same machine might be

regarded by one man as organised and by another as

unorganised” (Turing, 1948). The authors are fully

aware that some people are more susceptible to

deception than others. To mitigate interrogator

subjectivity the largest possible number of judges,

with a broad extent of expertise level and wide age

range, had been recruited for this experiment. In the

five transcripts we present here a judge misclassified

the machine for a human in the test, however, our

focus is on how the time was used by the interrogator

and machine. The exact time of the utterance in the

test is shown each box, and in every case ‘Local’ is

the interrogator judge, and ‘Remote’ is a hidden

interlocutor.

In the viva voce tests (Transcripts 1, 2) the one-

to-one transcripts between interrogator and machine

tell us the judges (Local) were able to use most of

the five minutes accorded to them.

Transcript 1: Judge J18 viva voce test session 1, round 1

Terminal E

[10:41:48] Local: Hello. How are you?

[10:41:53] Remote: Hey.

[10:42:16] Local: How do you like Bletchley |Park?

[10:42:20] Remote: lol.

[10:42:39] Local: Are you from England?

[10:42:47] Remote: They have Wi-Fi here in the pub.

[10:43:31] Local: Which pub?

[10:43:38] Remote: I'm just down the pub.

[10:44:03] Local: Have you ever been in a Turing Test

before?

[10:44:08] Remote: Will this be the 5 minute argument, or

were you thinking of going for the full half hour.

[10:44:55] Local: Very funny. You sound suspiciously

human. Do you like the Beatles?

[10:45:02] Remote: I'd like to get the next Dread the Fear

tape.

[10:45:20] Local: What is Dread the Fear?

[10:45:24] Remote: Dread the fear has that Steve

Henderson guy in it.

[10:46:08] Local: What sort of music is that? Or is it

comedy?

Both the machines (marked as Remote) in the

viva voce conversations were misclassified as human

by interrogator judges J18 (Transcript 1) and J20

(Transcript 2).

Transcript 2: Judge J20 viva voce test session 3, round 2,

Terminal D

[13:07:07] Local: Good morning, are you well?

[13:07:11] Remote: Yes. Are you?

[13:07:43] Local: Yes I'm very well. Are you happy that

the sun is shining?

[13:07:50] Remote: Yes.

[13:08:07] Local: Have you been on holiday this year?

[13:08:12] Remote: No.

[13:08:24] Local: Do you hope to?

[13:08:32] Remote: Yes.

[13:08:58] Local: Would you like to spend your days on a

beach or vist historic places?

[13:09:11] Remote: No.

[13:10:19] Local: What would you like to do then?

[13:10:28] Remote: I don't know.

[13:10:46] Local: Are you from the UK?

[13:10:52] Remote: No.

[13:11:12] Local: Where do you come from?

[13:11:16] Remote: Egypt

In contrast, in the simultaneous tests (Box 2, Box 3,

and Box 4) the conversations show, though wrongly

classed as human, the machines were more

loquacious than the human foils in the same test (left

Remote in Box 2; right in Box 3; right in Box 4).

Box 1: Judge J1 simultaneous test machine miscategorised

as human.

J1 with machine J1 with human foil

[12:23:19] Local: What is black

and white and read all over?

[12:23:32] Remote: I don't have

true sense of color perception I

am only able to see the RGB

values.

[12:24:08] Local: That's ok. Do

you like jokes?

[12:24:19] Remote: Please tell

me your inclination to a good

sense of humor first.

[12:24:40] Local: A person who

can laugh at one's self.

[12:24:46] Remote: Would you

like to hear a joke?

[12:24:54] Local: Yes, please.

[12:25:21] Remote: This joke has

been making the rounds in

robotic circles: A robot goes to

the doctor and says: "My left arm

is stuck. Give me a new arm."

The doctor answers: "Your arm is

fine. We'll have to replace the

rest of you."

[12:26:06] Local: Ha! Ha! Why

did the chicken cross the road?

[12:26:22] Remote: The chicken

wandered into the road because it

liked the shiny colors of the cars

and trucks whizzing by.

[12:27:39] Local: You're right. It

didn't care if it got to the

otherside.

[12:27:50] Remote: By the way,

did you ever actually see a

chicken crossing the road?

[12:28:03] Local: Only one that

didn't make it.

[12:24:17] Local: Hi, how are

you today?

[12:24:53] Remote: Im excellent,

how are you? What's you're

name. Im Buzz. I was named

after a lawnmower

[12:25:27] Local: You are the

first person I ever knew named

after a lawn mower. I'm Cathy.

[12:26:07] Remote: Hello Cathy.

Yes my parents were keen

gardeners. We lived in a glass

house... we weren't allowed to

play football much

[12:27:00] Local: There are

always soft balls for football. I

think your family has a great

sense of humour!

[12:27:56] Remote: Really? I

think they are quite cruel,

lawnmowers aren't great things to

be named after.

In the simultaneous conversation in Box 2,

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

562

interrogator judge J1 (Local) returned an incorrect

score of BOTH HUMAN for the two hidden

interlocutors: one was a machine feeding responses

to the left of the judge’s screen, the other a human

sending messages to the right. The conversation

shows J1 interacted more with the left entity,

machine (between 12.23.19pm-12.28.03pm) than

with the human (Box 2) feeding utterances to the

right of the screen (12.24.17pm-12.27.56pm).

J1 exchanged three utterances with the right

Remote (human) compared with seven shared with

the left, machine (see Box 2).

Judge J2 made a double error in a simultaneous

test by scoring the hidden human as a machine, and

the machine as a human (Transcript in Box 3).

Judge, J13 misclassified the machine as human in

the simultaneous test (Box 4).

Box 2: Judge J2- Double Error

J2 with human foil J2 with machine

[15:45:23] Local: Hi have you

been on line long

[15:45:34] Remote: just a few

seconds

[15:46:28] Local: Have you

been to see any good films

recently

[15:47:08] Remote: went to see

Avengers Assemble last

weekend, and hoping to see

Prometheus tomorrow

[15:47:28] Local: They seem a

bit serious

[15:47:54] Remote: Wouldn't

say that about Avengers

Assemble, just a bit of fun

[15:48:29] Local: do you

drive?

[15:48:39] Remote: when I

have too

[15:49:08] Local: I prefer the

bike myself

[15:49:30] Remote: train for

me, although bike is good for

recreation

[15:46:05] Local: My favourite

music is contemporary Jazz,

what do youy prefer

[15:46:14] Remote: To be short

I'll only say that I HATE

Britnie Spears. All other music

is OK compared to her.

[15:47:06] Local: do you like

to play any musical instruments

[15:47:23] Remote: I'm tone-

deaf, but my guinea pig likes to

squeal Beethoven's "Ode to

Joy" every morning. I suspect

our neighbors want to cut his

throat... Could you tell me

about your job, by the way?

[15:48:02] Local: Guine pig/

are you an animal lover

[15:48:08] Remote: Yeah. A

nice little guinea pig. Not some

annoying chatter bot.

[15:48:50] Local: do you live

with anyone else?

[15:48:59] Remote: Yes I do.

But better ask something else.

And I forgot to ask you where

you are from...

[15:49:39] Local: Ireland? geen

patures and too much rain!

How about you

The judge-interrogator J13 shared more utterances

(six) and more of the allowed five minutes with the

right remote entity (hidden machine) than with

hidden entity at remote left: four utterances with the

hidden human (Transcript in Box 4). This may

demonstrate that if a judge feels interested in one

conversation in a simultaneous test they may not pay

enough attention to the other hidden interlocutor

they are meant to be questioning in parallel.

The results from the experiment, and the content

of the conversations were intriguing and raised

questions, including: does being presented with a

hidden human first, rather than a machine, affect

interrogator accuracy in viva voce tests? Should the

simultaneous tests allow for a fixed number of

questions, rather than fixed time? Should the

duration of the simultaneous tests be twice as long as

the viva voce tests?

Box 3: Judge J13 simultaneous test machine

miscategorised as human

J13 with human foil J13 with machine

[16:06:30] Local: Hi there, do

you prefer to wear a dress or

trousers to work?

[16:06:49] Remote: that really

would be telling

[16:07:31] Local: What was

the last film you saw at the

cinema?

[16:07:40] Remote: Avengers

Assemble

[16:08:44] Local: cool, what

was your favourite game as a

child?

[16:09:08] Remote: Don't Miss

the Boat

[16:09:28] Local: tell me more

about that

[16:09:57] Remote: It's like

Ludo, but the end bits keep

moving around

[16:06:31] Local: Hi there, do

you prefer to wear a dress or

trousers to work?

[16:06:37] Remote: I am a

scholar. I'm too young to make

money.

[16:07:32] Local: What was the

last film you saw at the

cinema?

[16:07:38] Remote: Huh?

Could you tell me what are

you? I mean your profession.

[16:08:11] Local: I am an IT

manager and you?

[16:08:16] Remote: manager?

So how is it to work as

manager?

[16:09:13] Local: Hard work

but rewarding, what do you do?

[16:09:18] Remote: I am only

13, so I'm attending school so

far.

[16:09:51] Local: Have you

seen teletubbies?

[16:10:04] Remote: No, I

haven't seen it, unfortunately.

But I hope it is better than these

crappy Star Wars. And I forgot

to ask you where you are

from...

[16:10:15] Local: Brighton, and

you?

Box 6: Judge J13

simultaneous test machine

miscategorised as human

4 CONCLUSIONS

Our purpose for implementing Turing’s own two

tests (Shah, 2010), was to find which is more

difficult for the machine in the same duration to

achieve deception: is being interrogated alongside a

human for immediate comparison harder for the

machine imitating humanness, or being directly

FundamentalArtificialIntelligence-MachinePerformanceinPracticalTuringTests

563

questioned relying on the judge’s subjective

opinion? In our experiment the simultaneous

comparison trials were shown to be a more difficult

test for the machine than the viva voce tests. The

simultaneous test was also arduous for the

interrogator, because their focus was on two

dialogues in parallel.

Further experiments are planned to answer

questions raised here. Future tests are being

organised at The Royal Society in London, 7 June

2014. The authors encourage ICAART 2014

delegates to participate as judges or hidden humans

and try a practical Turing test to determine human

for machine themselves.

REFERENCES

Chip Vivant. 2012. Accessed 8.11.13 here:

http://people.exeter.ac.uk/km314/loebner/index.php.

Copeland, B. J., 2004. “The Essential Turing: The ideas

that gave birth to the Computer Age”, Oxford:

Clarendon.

Hodges, A., 2010. “Fair Play for Machines”, Kybernetes,

Vol. 38, No. 3.pp. 441-448.

Shah, H., 2010. “Deception-detection and Machine

Intelligence in Practical Turing tests”, PhD Thesis,

University of Reading, October 2010.

Shah, H., 2011. “Turing’s Misunderstood Imitaion Game

and IBM’s Watson Success”, 2

nd

Towards a

Comprehensive Intelligence Test, AISB Convention,

University of York, 5 May, pp. 1-5.

Shah, H., 2013. “Conversation, Deception and

Intelligence”, in S. B. Cooper and J. van Leeuwen

(Eds), Alan Turing – His Work and Impact, Elsevier.

Shah, H., and Warwick, K., 2010b. “Hidden Interlocutor

Misidentification in Practical Turing tests”, Minds and

Machines, Vol. 20, issue 3, pp. 441-454.

Shah, H., and Warwick, K., 2010a. “Testing Turing’s Five

Minutes Parallel-paired Imitation Game”, Kybernetes,

Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 449–465.

Turing, A.M., 1947. “Lecture on Automatic Computing

Engine”, in B.J. Copeland, The Essential Turing.

Oxford: Clarendon, pp. 378–394, 2004.

Turing, A.M., 1948. “Intelligent Machinery”, in B.J.

Copeland, The Essential Turing. Oxford: Clarendon,

pp.410–432, 2004.

Turing, A.M., 1950. “Computing machinery and

intelligence”, Mind, Vol. 59, No. 236, pp. 433–460.

Turing, A.M., 1951a. “Intelligent Machinery, A Heretical

Theory”, in B.J. Copeland, The Essential Turing.

Oxford: Clarendon, pp. 472–475, 2004.

Turing, A.M., 1951b. “Can Digital Computers Think?”, in

B.J. Copeland, The Essential Turing. Oxford:

Clarendon, pp. 482–486, 2004.

Turing, A.M., Braithwaite, R., Jefferson, G., and Newman,

M., 1952. “Can Automatic Calculating Machines Be

Said To Think?”, in B.J. Copeland, The Essential

Turing. Oxford: Clarendon, pp. 494–506, 2004.

Turing, A.M., 1953. “Chess”, in B.J. Copeland, The

Essential Turing. Oxford: Clarendon, pp. 569–575,

2004.

Warwick, K., and Shah, H., 2013. “Good machine

performance in practical Turing tests”, IEEE

Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in

Games. DOI: 10.1109/TCIAIG.2013.2283538.

Warwick, K., and Shah, H., (forthcoming) “Applying

Turing’s Imitation Game”, in J.P. Bowen, B.J.

Copeland, R. Whitty and R.J. Wilson, The Turing

Guide, Oxford: OUP.

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

564