Identifying Emotion in Organizational Settings

Towards Dealing with Morality

Terán Oswaldo

1,2

, Christophe Sibertin-Blanc

1

and Benoit Gaudou

1

1

IRIT, Université Toulouse 1 – Capitole, 2 rue du doyen Gabriel Marty, Toulouse, France

2

Dpto de Investigación de Operaciones and CESIMO, Universidad de Los Andes, La Hechicera, Mérida, Venezuela

Keywords: Modelling Morality, OCC Emotions, MABS, Systems of Organized Action, SocLab.

Abstract: Emotions play an essential role in the behaviour of human beings, either at their sudden occurrence or by

the continuous care to prevent the occurrence of unpleasant ones and to search for the occurrence of pleas-

ant ones. Notably, in any system of collective action, they influence the behaviours of the actors with re-

spect to each others. SocLab is a framework devoted to the study of the functioning of social organizations,

through the agent-based modelling of their structure and the simulation of the processes by which the actors

adjust their behaviours the one to another and so regulate the organization. This position paper shows how

SocLab enables to characterize the configurations of an organization that are likely to arouse different kinds

of social emotions in the actors, in order to cope with the emotional dimension of their behaviours. The case

of a concrete organization is introduced to illustrate this approach and its usefulness for a deeper under-

standing of the functioning of organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social simulation consists in the modelling of social

systems and the study of their behaviour by the per-

formance of computer simulations

(Axelrod, 1997),

including economics, organization, politics, history

or social-ecological systems (see for example the

JASSS on-line journal). The development of this

approach is due to the widening recognition that

social systems feature the characteristics of complex

systems: they display emergent behaviour not pre-

dictable from knowledge of their constituent so that

essential phenomena cannot be caught by analytical

approaches.

Regarding the simulation of social relationships

(Squazzoni, 2012), Sibertin-Blanc et al. (2013a)

proposes a formalisation of a well-experienced theo-

ry of the sociology of organization, the Sociology of

the Organized Action (SOA) (Crozier, 1964; Cro-

zier and Friedberg, 1980) which studies how social

organizations (for example a firm, an association,

any collective or a political setting) are regularized,

as a result of the counterbalancing processes among

the power relationships of the social actors. This

formalization is implemented in the SocLab envi-

ronment (El Gemayel, 2013) which enables to define

the structure of an organization as an instance of a

generic meta-model, to study its structural properties

in an analytical way, to explore the space of its pos-

sible configurations (and so to discover its Pareto

optima, Nash equilibriums, structural conflicts and

so on), and to compute by simulation how it is plau-

sible that each actor behaves with regard to others

within this organizational context. As far as one

agrees with the fundaments of SOA, this platform

looks like a tool for organizational diagnoses, the

analysis of scenarios regarding possible evolutions

of an organization or the study of phenomena occur-

ring within virtual organizations featuring particular

characteristics.

According to the SOA, the behaviour of each ac-

tor is strategic while being framed by a bounded

rationality. In this approach, the interaction context

defines a social game, where each actor adjusts his

behaviour with regard to others in order, as a meta-

objective, to obtain a satisfying level of capability to

reach his goals. The aim of a social game is to find

stationary states, i.e., configurations where actors no

longer modify their behaviour because each one sat-

isfies himself with the level of capability he obtains

from the current state of the game, so that the organ-

ization is in a sustainable regularized configuration.

The SocLab framework has been applied to the

study of concrete organizations (see e.g. Sibertin et

al., 2006; Adreit et al., 2010; El Germayel et al.,

2011; Sibertin et al., 2013a) on the basis of sociolog-

284

Oswaldo T., Sibertin-Blanc C. and Gaudou B..

Identifying Emotion in Organizational Settings - Towards Dealing with Morality.

DOI: 10.5220/0004919402840292

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2014), pages 284-292

ISBN: 978-989-758-016-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

ical inquiries. However in some cases, the simula-

tion algorithm that makes actors to play the social

game (Sibertin et al., 2013b) provides results about

the behaviour of some actors that do not accurately

match the field observations.

This gap between the observed and computed

behaviours can be ascribed to the fact that SocLab

neglects emotions. However, it is well know that

emotions contribute to the regulation of social actors'

behaviours together with phenomena such as mime-

sis (Selten et Ostmann, 2001) or reputation and trust

(Giardini et al., 2013). Indeed, social behaviours are

not so much driven by abstract reasoning than by

complex feelings that are produced by the interac-

tion context and perceived by the partners. Emotions

contribute to the regulation of behaviours that

emerges in human groups from the mutual adapta-

tion of each one’s behaviour to behaviour of others.

“Emotion regulation processes are important as

they enlist emotion to support adaptive, organized

behavioral strategies” (Clark, 1992).

Thus, in order to improve the verisimilitude of

the actors’ behaviours computed by the simulation

algorithm, and so the reliability of the provided re-

sults, the SocLab platform must cope with social

emotions. The first step in this way is to characterize

the configurations of an organization that are able to

trigger emotions in an actor and to further question

simulation results that reveal to be highly prone to

launch emotions. Such information could be very

useful from a sociological point of view to confirm

or not the stability of an organization. In particular,

it is likely that an actor with negative emotions

which, in addition, is endowed with a significant

power, will seek to make the structure of the organi-

zation to evolve toward a social game whose rules

are more favourable for him.

The further step is to integrate emotions into the

algorithm that implements the actors' decision-

making processes, so that simulations yield organi-

zational configurations that take into account strate-

gic emotions. To this end, actors must seek not only

getting the means to achieve their own goals but also

preventing (promoting) of the occurrence of config-

urations able to arouse negative (positive) emotions.

The remaining of the paper is structured as fol-

lows. Emotions are understood in many ways and

we first have to define what kinds of emotions we

consider and how they are characterized. We refer to

this end to the well-known Ortony, Clore and Col-

lins (Ortony et al., 1988) model that is presented in

section 2. Section 3 layouts the SocLab modelling of

organizations and the actors' decision process in

order to introduce the variables which characterize

social configurations. Then, we associate to each

kind of emotion indexes which values characterize

configurations likely to trigger this emotion in cer-

tain actors. The fourth section applies this frame-

work to a concrete system of organized action which

is somehow problematic. After a short presentation

of this organization and an overview of its SocLab

model (all relevant details are given in Terán et al.,

2013

), we give the values of the indexes for the con-

figuration resulting from simulations and their inter-

pretation in terms of actors' emotion.

2 ORTONY THEORY OF

EMOTIONS

We use the theory of Ortony, Clore and Collins (Or-

tony et al., 1988) (OCC) for the characterisation of

the various kinds of emotions because: (1) it is well-

funded and recognized as a standard in computer

science, notably in MABS; and (2) it deals with

most social emotions we have to consider.

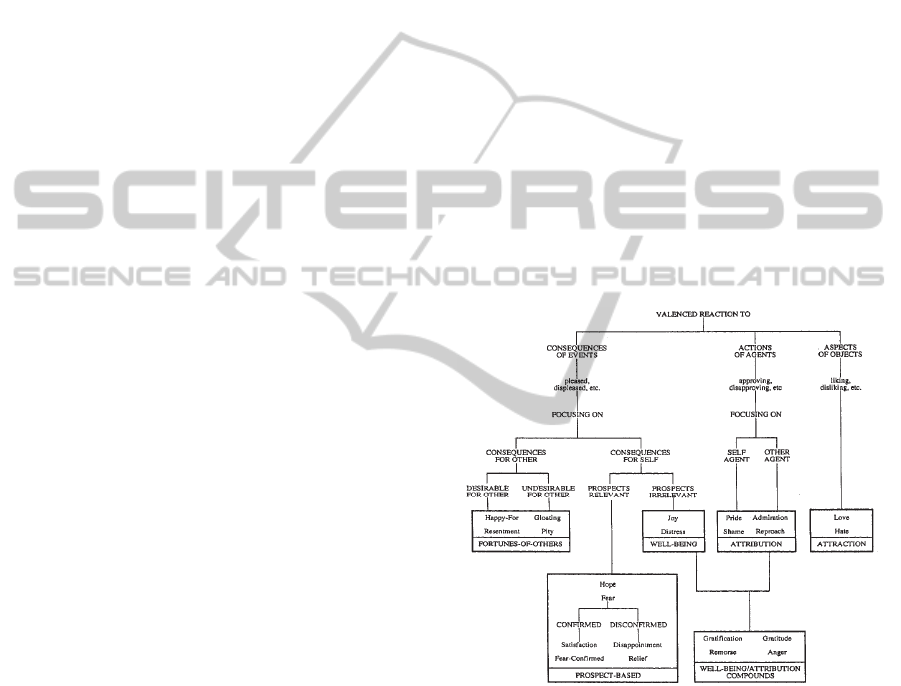

Figure 1: Ortony et al. (2000, pp 30) classification of emo-

tions.

Following OCC, emotions are linked to events, to

actions of people (oneself or other), or to objects.

The linked item might be actual or prospective, and

an emotion might have a desirable or undesirable

character to the extent it might affect the achieve-

ment or not of a goal, comply with or violate a moral

norm, or be associated with a liked or disliked ob-

ject. Emotions are then classified in a tree structure

(see Fig. 1), as follows: (1) in case the linked ele-

ment is an event that affects the achievement of a

goal, the outcome of the event is appraised either as

IdentifyingEmotioninOrganizationalSettings-TowardsDealingwithMorality

285

desirable or as undesirable, and the actor feels either

pleased or displeased, correspondingly; (2) in case

the linked element is an action that complies or not

with a behavioural norm, the actor appraises the ac-

tion either as praiseworthy or blameworthy, and his

reaction will be either approval or disapproval; (3) in

case the linked element is an object, the actor ap-

praises the object either as appealing or unappealing,

and so he will either likes or dislikes it. In SocLab

only the two first kinds of emotions appear: goal-

based (e.g. related with properties of a configuration

whose occurrence is an event), and norm-based (e.g.

regarding the behavior of one actor toward another

one). This will be better explained in section 3.1

3 IDENTIFYING EMOTIONS

IN SocLab

To enable the modelling of social relationships be-

tween the actors of organizations, SocLab proposes

a meta-model that catches the common concepts and

properties of social organizations and is instantiated

on specific cases as models of concrete or virtual

social organizations or Systems of Organised Action

(Crozier, 1964; Crozier and Friedberg, 1980). Ac-

cordingly, the model of the structure of an organiza-

tion is composed of instances of actors and relations

that are linked by the control and depend associa-

tions.

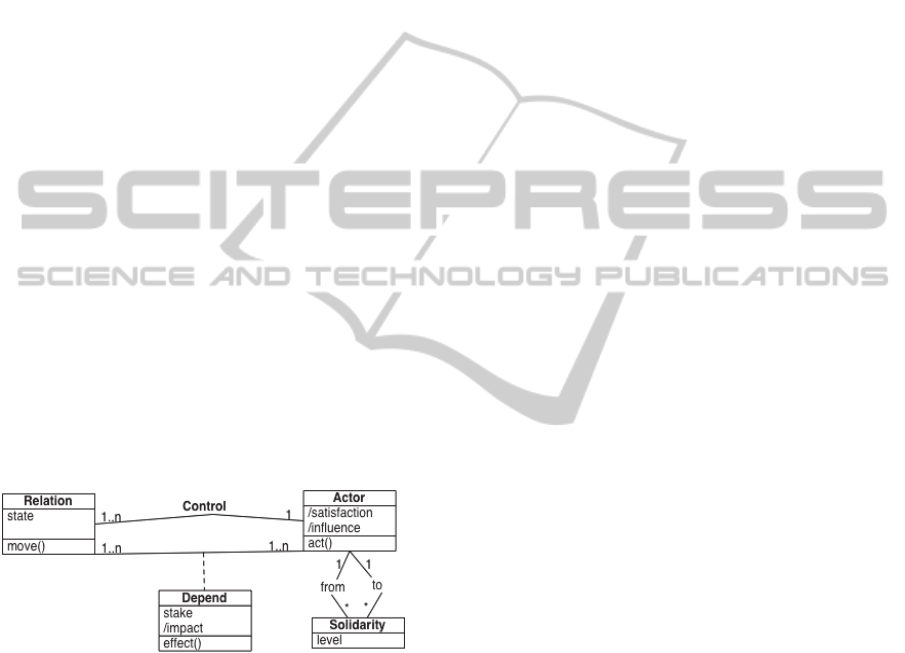

Figure 2: The core of the meta-model of the structure of

Systems of Organized Action.

Figure 2 shows the meta-model of organizations'

structures, as a UML class diagram. A relation is

founded on an organization’s resource, or a set of

related resources, and it is controlled by a single

actor. Resources are material or cognitive (factual or

procedural believes or expectations) elements re-

quired to achieve some intended actions, so that their

availability is necessary for some actors. The state

attribute of a relation represents the behaviour of the

controller actor with regard to the availability of the

resource for the ones who needs it. Its range of value

SB goes from the least cooperative behaviours of the

controller preventing the access to the resource to

the most cooperative behaviours favouring this ac-

cess, while the zero value stands for neutral behav-

iours.

The stake attribute of the dependence of an actor

on a relation corresponds to the actor's need of the

relation to reach its own goal, on a scale:

null = 0, negligible = 1,… ,significant = 5,… , critical = 10.

The effect function evaluates how much the state

of the relation makes the resource available to the

actor, so that effect

r

: A x SB

r

---> [-10, 10] has

values in:

worst access = -10, ..., neutral = 0, ...,optimal access =10.

In addition, actors may have solidarities the ones

with regard to others, defined by as function solidar-

ity(a, b) ---> [1, -1] where negative values corre-

sponds to hostilities and positive values to effective

friendships.

Defining the state, or configuration, of an organ-

ization as the vector of all relations states, each state

of the organization determines on the one hand how

much each actor has the means he needs to achieve

his goals, defined as:

satisfaction(a, s) =

c

A

r

R

solidarity(a, c)*

stake(c, r) * effect

r

(c, s

r

)

and on the other hand how much he contributes to

the satisfactions of each other actor, defined as:

influence(a,b,s) =

r

R; a controls r

c

A

solidarity(b,c)* stake(c, r) * effect

r

(c, s

r

).

This interaction context defines a social game,

where each actor seeks, as a meta-objective, to ob-

tain from others enough satisfaction to reach its

goals and, to this end, adjusts the state of the rela-

tions he controls. Doing so, it modifies the value of

its influence and therefore the satisfaction of actors

who depend on the relations it controls

.

The aim of a social game is to reach a stationary

state: there, actors do no longer change the state of

the relations they control, because every one accepts

his level of satisfaction provided by the current state

of the game, so that the organization is in a regular-

ised configuration.

The actors' strategic attitude is framed by a

bounded rationality (Simon, 1982). The simulation

module of SocLab makes the actors to play the so-

cial game (El Gemayel et al., 2011; Sibertin et al.,

2013b). The model of the actors' rationality is im-

plemented as a process of trial and error based on a

self-learning rules system. Each actor manages a

variable that corresponds to his ambition, and the

game ends when the satisfaction of every actor ex-

ceeds his ambition.

To sum up, each simulation run yields a regularised

configuration which associates to each actor numeri-

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

286

cal values of its satisfaction and its influence, and

these values may be used to determine whether this

configuration is able to arouse a kind of emotion.

3.1 Indexes of Emotions in SocLab

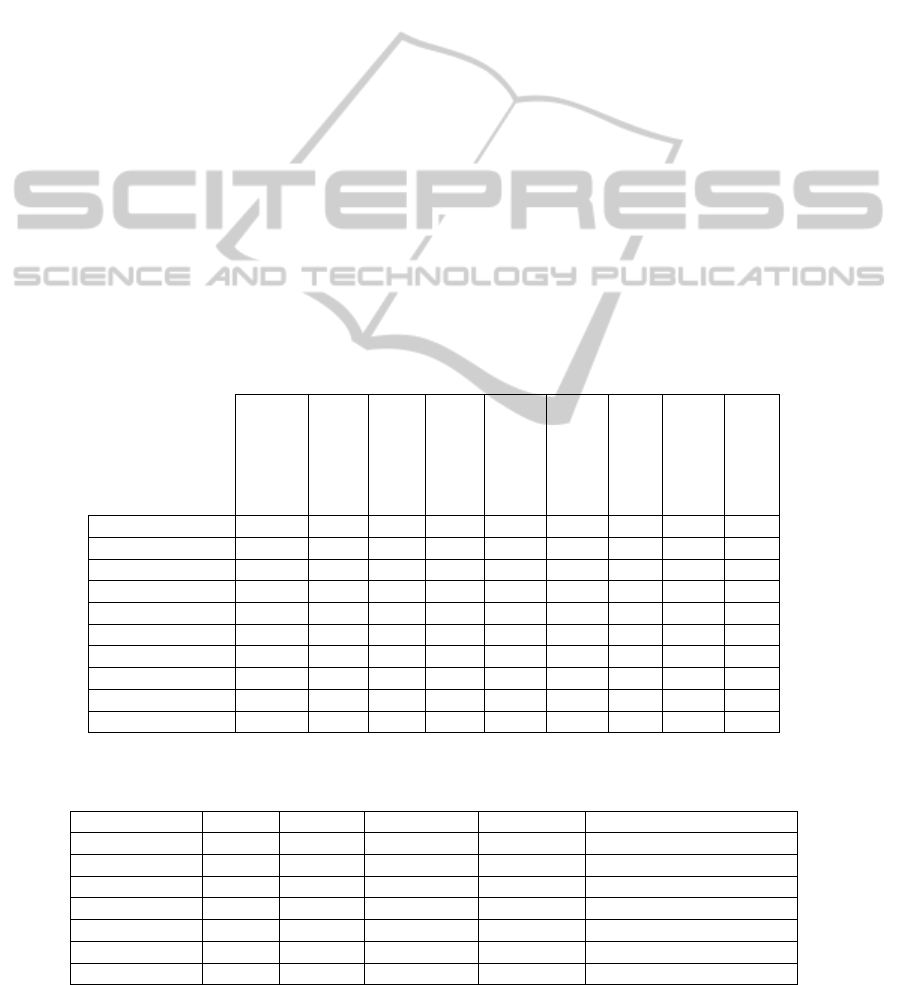

Table 1 shows the emotions a SocLab actor is likely

to feel in a given configuration of the organization.

Table 1: Emotions experienced by an actor in SocLab.

Power (influence) exercised by

Self Other The Whole organization

Satisfaction Received by

Self

gratificat

/remorse

gratitude

/Anger

joy/distress

Other

pride

/guilt

admirat/

reproach

If pleased/displeased about

° desirable event:

happy-for/resentment

—-----------------------------------------------

° undesirable event:

gloating/pity

The

Whole

pride/

shame

admirat/

reproach

As above

On one hand, the OCC norm-based emotions are

associated with the action done by agents, let us say

A, what in SocLab is an individual actor, A itself,

another actor, the whole organisation (the whole set

of actors, including A) or all others (all actors ex-

cluding A). On other hand, the goal-based emotions

are based on configurations related with the

achievement of a goal. An OCC event is understood

in SocLab as a configuration where the actor reaches

in some degree its aim. The event is given by the

configuration and properties of the game, including

those of the actors. For clarity we will prefer to talk

about the configuration rather than about an event.

The occurrence and intensity of each emotion is

identified by an index which is defined on the basis

of a proportion, or a percentage. The index is a com-

parison between what is actually done (e.g., the in-

fluence given by the actor) and what could be done

(e.g., the potential for giving). Indeed, a social actor

“appraises” the situation in the context of the possi-

bilities available for it. The emotional interpretation

of the values of each index depends on the very na-

ture of the organization under consideration and of

individual traits of the actor A. Globally, considering

as an example the Joy/Distress emotions, one could

consider that Joy appears above 70% and distress

under 50%.

These indexes are not variables used by the

agent in its decision making process. They are based

on the essential properties of configurations, i.e.

what is given (Influence or Inf) from A to B, or in

what is received (Satisfaction or Sat) by A from B,

where A and B may be: a particular actor, the whole

organisation or all the other actors, as shown in Ta-

ble 1. For instance, we will call minSat(A) (resp.

maxSat(A)) the minimal (resp. maximal) Satisfac-

tion A can receive from the whole. The same stands

for minInf(A) and maxInf(A). Similarly, Sat(A, s)

(resp. Inf(A, s)) stands for the Satisfaction (resp.

Influence) of A at configuration s.

1. Well-being emotions: Joy/Distress

The OCC model defines joy (distress) as: to be

pleased (displeased) about the occurrence of a desir-

able (undesirable) event, or the (regulated) configu-

ration resulting from such an occurrence. In So-

cLab, the joy/distress of an actor A is defined as:

Joy(A,s) = (Sat(A,s) - minSat(A)) / (maxSat(A) -

minSat(A))

2. Gratification/Remorse

OCC defines gratification (remorse) as being

pleased (displeased) about a desirable (undesirable)

event or situation that results from oneself action

and thus entails the approving (disapproving) of

one's own praiseworthy (blameworthy) action. Thus:

Gratif(A, s) = (Inf(A, A, s) – minInf(A, A)) / (max-

Inf(A ,A) - minInf(A,A)

).

3. Pride/Guilt and Pride/Shame

An actor could feel prideful (guilty or shameful)

when he approves (disapproves) his praiseworthy

(blameworthy) action regarding its effect on another

or on the whole. Thus, Pride (Guilt) of A with regard

to B is:

Pride(A, B, s) = (Inf(A, B, s) – minInf (A, B)) /

(maxInf (A, B) - minInf (A, B)).

Replacing B by O (all the others) we have the

Pride (Shame) of an actor A with regard to all oth-

ers.

Similarly, the Pride (Shame) of A with regard to

the whole organization is defined as:

Pride(A, W, s) = (Inf(A, s) - minInf(A)) / (maxInf(A)

- minInf(A)).

4. Gratitude/Anger.

The OCC model defines gratitude (anger) as to be

pleased (displeased) about the consequences for

oneself of another's praiseworthy (blameworthy)

action. Thus gratitude (anger) is similar to gratifica-

tion (remorse), but it regards what is given by the

other instead of what is given by oneself. We define

IdentifyingEmotioninOrganizationalSettings-TowardsDealingwithMorality

287

the Gratitude (Anger) of A towards B as:

Gratitude(A, B, s) = (Inf(B, A, s) – minInf(B,A)) /

(maxInf(B ,A) – minInf(B,A)).

5. Admiration/Reproach

Admiration (reproach) is related to approving (dis-

approving) some other's praiseworthy (blamewor-

thy) action, evaluated wrt the consequences for an-

other actor B, for all others, or for the whole organi-

zation. More precisely, Actor A evaluates the influ-

ence given by actor B considering its consequences

for C, in accordance to the solidarity A feels towards

C. This can happen either because A perceives the

consequence for C of B’s action, or the feeling of B

towards C (sharing of emotions). Thus, the Admira-

tion (Reproach) of A towards B, given the A's soli-

darity towards C, is:

Admiration(A,B,C,s) = Gratitude(C,B,s) * Solidarity(A,C)

The sign of Solidarity(A, C) determines whether A

feels Admiration (positive) or Reproach (negative)

towards B.

6. Happy-for/resentment, and Gloating/pity

These emotions appear when the actor perceives

what is happening for another particular actor as a

consequence of a configuration resulting from col-

lective action. Example: an actor B is getting a low

capacity while it is giving a lot; this means that he is

collaborative and expects the others to be so towards

him, and the low collaboration from others toward

him is unjust. Under this situation, if an actor A has

negative (positive) solidarity towards actor B, then

A feels pleased (displeased) by what is happening to

B, and so A would feel gloating (pity) in the follow-

ing proportion:

Pity (A, B, W, s) = Abs[Joy (B, W, s) – Pride (B, W, s)]/

Joy (B, W, s) * Sol (A, B);

Notice that (Joy(B, W, s) - Pride(B, W, s)) is nega-

tive (undesirable). Pity (gloating) occurs if solidarity

is positive (negative). When (Joy(B, W, s) - Pride(B,

W, s)) is positive (desirable), the same equation de-

fines

Happy-for/resentment.

4 THE CASE

The model of a concrete team is introduced to ex-

emplify how emotions and morality can be identified

in SocLab, and to illustrate how such identification

can help in auditing organisations or designing poli-

cies for promoting collaboration. The team is in

charge of designing a methodology for Institutional

Planning in the Public Sector (we will call it Team

for Designing a Planning-Methodology, or TDPM).

The model has been developed in interaction with

persons who are or have been involved in the TDPM

team, with whom also the simulation results have

been shared and discussed (a precise description of

the TDPM's model is given in (Terán et al., 2013))

.

TDPM is part of a Public Foundation entrusted

with the investigation and development of socially

pertinent free technologies, which in turn is part of

the Ministry for Science and Technology of a

LatinAmerican country. That Public Foundation has

four departmental units for its basic activities, and a

Management Unit. The basic units are:

─ Pertinence Unit: advises other units about the

relevance of technologies.

─ Development Unit: produces the tools for the

methodologies.

─ Research Unit: designs free technologies meth-

odologies, organisational forms and tools.

─ Technological Spreading Unit: spreads the use

of the methodology.

4.1 The TDPM Team

The TDPM's model includes seven actors coming

from all the five units of the Public Foundation (an

actor can correspond to several similar concrete

member of an organization): two actors from the

Research Unit, two actors from the Development

Unit, and one from each of the three other units. The

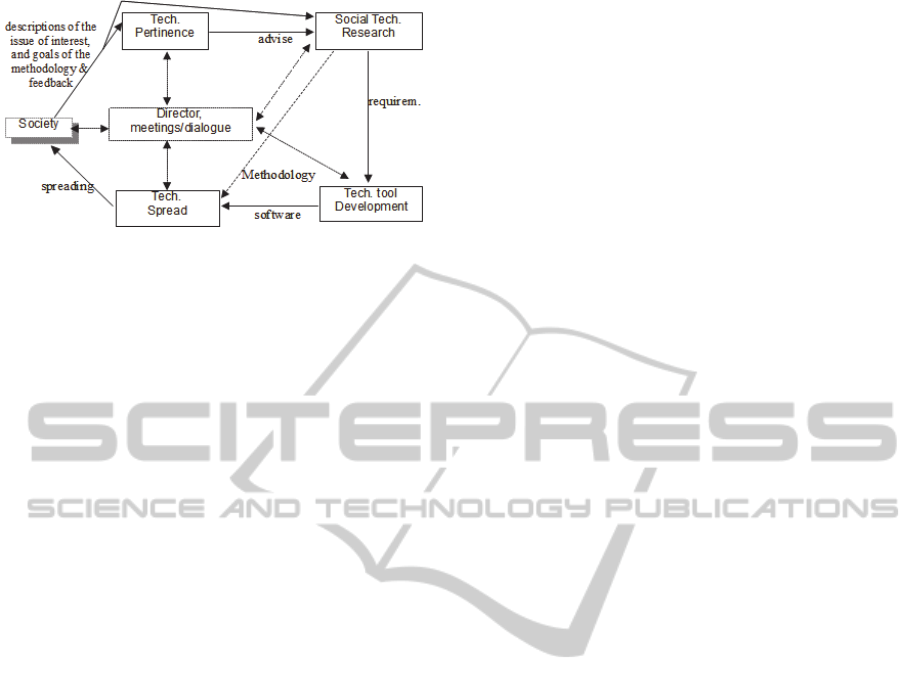

work process the TDPM follows the cycle shown in

Fig. 3. Each actors of the team has some duty and

controls some relations, as explained below:

─ Director. It controls the relations: controlWork

and materialSuport. The first one consists in work

report and evaluation mechanisms, and the sec-

ond one on all material assistance.

─ researcherS. It designs the planning methodolo-

gy, and specifies the requirements of the tools. It

controls the relation researchMethS.

─ researcherO. It operatively helps the Research-

erS. It controls the relation researhMethO.

─ developerS. It develops software tools, and so

controls the relation develToolS.

─ developerO. It helps the developerS actor opera-

tively, developing particular functionalities of the

software, controlling the relation develToolO.

─ pertAdviserS. It is responsible for advising the

rest of the team about the social pertinence of the

methodology, controlling the relation pertinence.

─ techSpreaderO. It is responsible for technological

spread, for promoting the use of the methodology,

controlling the relation techSpread.

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

288

Figure 3: Activities of the team developing the planning

methodology. It completes a cycle begging by identifying

requirements of the society, and finishing with spreading

the product (methodology) into the society.

The two following attitudes are found:

─ some actors of the team are highly engaged, crea-

tive, and thus their work is key for the team;

─ other members of the team are weakly engaged,

distanced, and their work is little productive and

slightly supports the TDPM's aims.

In the TDPM team, the actors pertAdviserS, re-

searcherS and developerS reveal to be highly en-

gaged; while the other four actors are distanced at

different degrees.

4.2 Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of influences and

satisfactions at the regularised configuration result-

ing from simulations. Table 3 gives the intensities of

Joy, Pride, Gratification and Gratitude felt by the

actors at this configuration. For Gratitude particular

cases are presented, indicating towards whom the

actor feels such an emotion. The other emotions,

namely Admiration/Reproach, Happy-for/ Resent-

ment and Gloating/Pity, do not appear in the present

model because there are not significant solidarities

between actors.

From Table 3 we see that all actors have a good

level of Joy and Gratification. In particular, re-

searchO has the minimal value of Joy, while per-

tAdviserS has the maximal one.

An interesting result appears when we compare the

values of Pride to the Whole (Pride_W) and Pride to

others (Pride_O). Pride to the whole is high for all

actors but in some cases Pride to others is low. This

means that some actors give a lot to themselves but

little to others. The worst case is that of tech-

SpreaderO, followed by developerO (0.29 and 36.3,

respectively). The techSpreaderO case is critical and

should strongly affect the performance of the team.

Also the Director is not very much engaged

(Pride_O is only

52.7%), somewhat affecting the

performance of the team.

This case illustrates how the level of moral emo-

tions is correlated with the level of engagement of

the actors, and could help in defining policies to

improve actors’ engagement and so the organisa-

tion's performances. In particular, actions aiming at

favouring (in some actors) pride to all the others

could be beneficial. Afterwards, those policies can

be improved from careful feedback about the gener-

ated changes in the actors’ engagement and emo-

tions. In the long term, the promotion of appropriate

emotions would be aimed at establishing desirable

organisational norms.

5 RELATED WORK

Different formalizations of OCC can be found in the

literature, see for instance Steunebrink et al. (2012)

or Adams (2010). These formalizations represent

formal descriptions of the qualitative aspects of

emotions (or conditions to happen), which indicates

when an emotion is triggered. On the other hand,

quantitative aspects of emotions (e.g., emotion in-

tensity) addressed in the present paper has received

scarce treatment. One work in this area is offered by

Steunebrink et al. (2008).

OCC does not specify in detail how to deal with

the quantitative aspect of emotions, apart from men-

tioning some variables on which emotions depend,

and giving some hints about how to manage the

quantitative aspect of emotions, by using the varia-

bles potential, threshold and intensity. Intensity is

defined as the difference between potential and

threshold (see Steunebrink et al.; 2008, p. 3). For

instance, the potential (and thus the intensity) of

some emotions related with the action of agents is

affected by the variables degree of praiseworthiness

(blameworthiness), degree of desirability and degree

of effort. In particular, the effect of these variables

can be considered linear: potential is a weighted sum

of the named variables. In general, in OCC, potential

is defined in terms of the Central Intensity Variables

and the Local Variables.

Similarly, only hints are given in OCC about

how to define the qualitative value of the threshold

of emotions: they might be determined in terms of

Global Variables which are related with the “mood”

(a kind of disposition) of the individual; e.g., if the

individual general feeling or “mood” becomes more

agreeable than in a previous state, then the threshold

of negative emotions would be increased in relation

to the values at that previous state. Among the OCC

Global Variables, we have: sense of reality, and the

IdentifyingEmotioninOrganizationalSettings-TowardsDealingwithMorality

289

subjective importance of a situation.

Alike OCC, Steunebrink et al. (2008) does not

study the variables affecting the intensity of emo-

tions, but instead concentrates on the integration of

qualitative aspects into the logical formalization of

OCC. For this, they need to describe not only the

initial value of an emotion, but also how its value

changes over time, decreasing until disappearing or

being negligible, what is represented via an inverse

sigmoid function.

5.1 Our Approach

In SocLab the interest is in the regularized configu-

ration resulting from simulation, where certain prop-

erties occurs according to the state of each relation

and the values of each actor’s Influence (what is

given) and Satisfaction (what is got). In this sense,

we can say that the resulting intensities of the emo-

tions are regulated emotional states, which can be

related with measures of central tendency (e.g.,

means, medians, or modes). Thus, the interest is not

in simulating the dynamics of emotions as in

Steunebrinck et al. (2008); i.e., the aim is not to

simulate the conditions in which emotions occur, or

their initial and subsequent values over time.

In this sense, we take a different approach from

that of Steunebrinck et al. (2008). The determination

of emotions rests in relational properties of the ac-

tors, associated with the actors’ aims and morality;

that is, emotions are defined in terms of what an

actor gives and what an actor receives. It is supposed

that the conditions for the emotion are fulfilled at the

regulated state, and so we do not need to test them.

However, the intensity of an emotion is not nec-

essarily positive, as it might also be either null or

negative. As emotions of interest in SocLab are de-

fined in pairs (e.g., pride vs. shame), if the intensity

is positive, then the positive component happens,

otherwise the negative component is the case.

Thus, the paper focuses in determining the inten-

sity of each emotion, which for simplicity here is

assumed to be equal to its potential (the threshold is

0). However, alike OCC and Steunebrink et al.

Table 2: The exerted influence (in columns) and obtained satisfaction (in lines) by the actors of the TDPM team at the con-

figuration resulting from simulations. The last column shows the percentage of satisfaction each actor receives from all

actors in relation to what it can get. Similarly, the last two lines show the actual percentage of influence each actor gives to

the Whole and to all the Others, in relation to what it can give.

Director

researcherS

researcherO

developerS

developerO

pertAdviserS

techSpreaderO

Satisfaction

%SatifWhole

Director 29.8 15 0.8 15 0 6.9 -5.9 61.5 89.7

researcherS 2.3 40 1.5 7.2 -0.8 6.9 -5.9 51.1 86

researcherO -0.4 -4 14.8 0.9 -0.2 0 0 11.1 71

developerS -1.8 25 1.5 36 -2.3 0 0 58 85

developerO -2.7 4 0.3 18 19 0 0 38 89

pertAdviserS 2.7 20 0 18 -0.4 24.3 -4.9 59.5 90

techSpreaderO -0.6 0 0 0 0 0 45 43.9 72

Influence 29.2 100 18.8 95.1 15.4 38.1 28 46.3

% Inf. To Whole 78.9 100 95.6 100 93.1 99.5 100

%Inf. To Others 52.8 100 59.2 100 36.3 99.3 0.3

Table 3: Intensity of emotions felt by the actors of the TDPM team in the configuration described in Table 2.

For Gratitude only examples are given.

Joy Gratif Pride_O Pride_W Gratitude Towards

Director

89.7 97.68 52.7 78.9 20.5 techSpreaderO

researcherS

85.5 100 100.0 100 99 techSpread.

researcherO

71.3 97 59.2 95.6 99.3 perAdviserS

developerS

84.7 95 100.0 100 100 researchS

developerO

89.4 94.8 36.3 93.1 95 developerS

pertAdviserS

90.2 99.6 99.29 99.5 52 direcctor

techSpreaderO

72 99.6 0.29 99.5 - developerO

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

290

(2008), we do not concentrate on specifying either

the variables determining the intensity or the varia-

bles indicating the threshold of the emotions. For

instance, for the case of Pride and Gratification, the

emotion intensity results from evaluating what the

actor is given to itself or to others, in relation to

what it can give. This might be seen as a conse-

quence or as measure of the actor’s morality. On the

other hand, the index of Joy focuses on what the

actor is receiving, in comparison to what it can re-

ceive, what measures the degree of achievement of

the actor goals.

It is important to notice the introduction of the

notion of solidarity, which is missing in Steunebrink

et al. as in OCC. This allows differentiating a diver-

sity of relationships between an actor and the others.

For instance, Admiration of actor A towards actor B

might happen not only because the action of B is of

direct interest for A, but also because it is of interest

for an actor C to whom A feels solidarity. This per-

mits to considerably increase the richness of the de-

scribed social relationships.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The paper show how emotions can be identified in

SocLab models of organizations by the definition of

indexes that evaluates the potential arousal of moral

emotions such as pride and guilt. Considering a con-

crete organization, it has illustrated how the

knowledge of the actors' emotional states improves

the understanding of the functioning of an organiza-

tion.

Considering the fact that social actors try to pre-

vent bad emotions and reach good ones, this opens

the way for the simulation algorithm to cope with

the emotions of actors. In the case study, the indexes

show low levels of moral emotions for some actors,

and thus, e.g., help in a diagnosis of the organisation

in order to design policies to improve the level of

engagement of those lowly engaged actors. These

policies would promote desirable norms of behav-

iour, taking into account moral emotions as incen-

tive/punishment in settling and strengthen those

norms, in order to increase collaboration in the or-

ganisation. This issue will be addressed in further

research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by the French ANR

project EMOTES “Emotions in social interaction:

Theoretical and Empirical Studies”, contract No.

ANR-11-EMCO 004 03.

REFERENCES

Adam Carole, 2007. Emotions: From Psychological Theo-

ries to Logical Formalization and Implementation in a

BDI agent. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Toulouse,

Toulouse, France. 216 p.

Andreit, F., Roggero, P., Sibertin-Blanc, C. and Vautier,

C., 2011. Using SocLab for a Rigorous Assessment of

the Social Feasibility of Agricultural Policies. Interna-

tional Journal of Agricultural and Environmental In-

formation Systems 2(2), p. 1-20.

Axelrod, R., 1997. Advancing the Art of Simulation in the

Social Sciences. In R. Conte, R. Hegselmann and P.

Terna (Eds), Simulating Social Phenomena (pp. 21-

40). Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical

System. Springler-Verlag.

Clark M, 1992. Emotion and social behavior (Ed), Sage

Publications.

Clore, Gerald L. and A. Ortony, 2000. Cognition in emo-

tion: Always, sometimes, or never. In Cognitive neu-

roscience of emotion, edited by Richard D. Lane, and

Lynn Nadel, 24-61. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Crozier, M., 1964. The Bureaucratic Phenomenon. Chica-

go: University of Chicago Press.

Crozier M. and E. Friedberg, 1980. Actors and Systems:

The Politics of Collective Action. The University of

Chicago Press.

El-Gemayel, J., Chapron, P., Sibertin-Blanc, C (2011).

Impact of Tenacity upon the Behaviors of Social Ac-

tors. Advances in Practical Multi-Agent Systems, Quan

Bai and Naoki Fukuta (Eds), Studies in Computational

Intelligence 325, p. 287-306, Springer.

El-Gemayel J., 2013. Modèles de la rationalité des acteurs

sociaux. PhD of the Toulouse University, France.

Giardini F., R. Conte, and M. Paolucci, 2013. Reputation.

Chapitre 15 In Simulating Social Complexity - A

Handbook, Bruce Edmonds and Ruth Meyer Editors.

Springer.

Ortony, A., Clore, G., and A. Collins, 1988. The cognitive

structure of emotions. New York: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Selten, R., Ostmann, A, 2001. Imitation Equilibrium. Ho-

mo Oeconomicus 43, 111–149.

Sibertin-Blanc, C., Amblard, F. and Mailliard, M. (2006).

A coordination framework based on the Sociology of

Organized Action. In Coordination, Organizations,

Institutions and Norms in Multi-Agent Systems, O.

Boissier, J. Padget, V. Dignum and G. Lindemann

(Eds), LNAI, 3913, 3-17. Springer.

Sibertin-Blanc, C. Roggero, F. Adreit, B. Baldet, P.

IdentifyingEmotioninOrganizationalSettings-TowardsDealingwithMorality

291

Chapron, J. El Gemayel, M. Mailliard, and S. Sandri,

2013a SocLab: A Framework for the Modeling,

Simulation and Analysis of Power in Social Organiza-

tions, Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simu-

lation (JASSS), 16(4). http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/

Sibertin-Blanc, C. and El Gemayel J. 2013b. Boundedly

Rational Agents Playing the Social Actors Game -

How to reach cooperation. Proceeding of IEEE Intelli-

gent Agent Technology, V. Raghavan (Ed.), 17-20

nov. 2013, Atlanta.

Simon, H. A., 1982. Models of bounded rationality: Be-

havioral economics and business organization. The

MIT Press.

Squazzoni, F., 2012. Agent-Based Computational Sociol-

ogy, Wiley.

Staller A. and P. Petta, 2001. Introducing Emotions into

the Computational Study of Social Norms: A First

Evaluation, Journal of Artificial Societies and Social

Simulation vol. 4, no. 1.

Steunebrink, B. R., Dastani, M. M. & Meyer, J-J.Ch.,

2008. A Formal Model of Emotions: Integrating Qual-

itative and Quantitative Aspects. In G. Mali, C.D. Spy-

ropoulos, N. Fakotakis & N. Avouris (Eds.), Proceed-

ings of ECAI'08, pp. 256-260. IOS Press.

Steunebrink, B. R., Dastani, M. M. & Meyer, J.-J.Ch.,

2012. A Formal Model of Emotion Triggers: An Ap-

proach for BDI Agents. Synthese, 185(1):83-129,

Springer.

Terán, O., and Sibertin-Blanc C., 2013. Social Model of a

Team Developing a Planning-Methodology. OpenAbm

http://www.openabm.org/model/3983/version/1/view.

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

292